User login

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

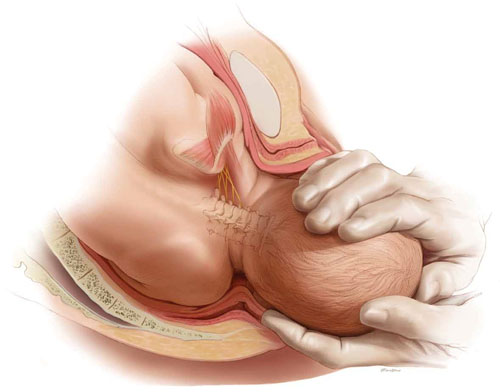

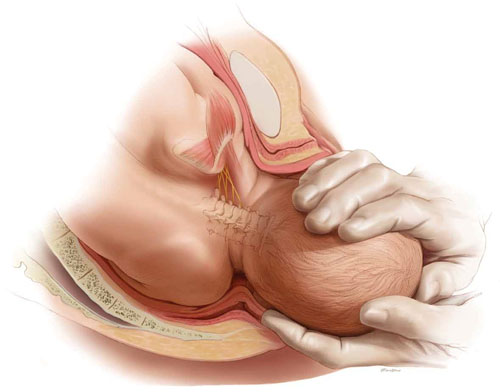

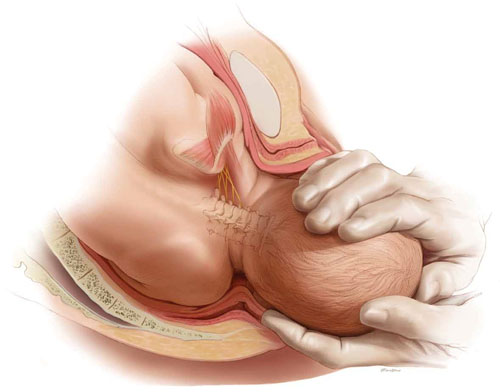

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.

Recognize the benefits of partnership

Forging a partnership with the patient:

- improves the accuracy of information

- eases ongoing communication

- facilitates informed consent

- provides an opportunity for you to educate her.

TABLE 2 When building trust, both patient and physician

are charged with responsibilities

| In regard to … | The patient’s responsibility is to … | The physician’s responsibility is to … |

|---|---|---|

| Gathering an honest and complete medical history | Know and report | Question completely |

| Being adherent to prescribed care | Follow through | Make reasonable demands |

| Making decisions about care | Ask questions and actively participate in choices Make realistic requests | Be knowledgeable about available alternatives Individualize options |

Key concept #3

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Patient and physician both have responsibilities that are important to achieving an optimal outcome; so does the hospital (TABLE 2 and TABLE 3). Both patient and physician should practice full disclosure throughout the course of care; this will benefit both of you.4 Here are a few select examples.

TABLE 3 Relative degrees of responsibility for a good outcome

vary across interested parties, but none are exempt

| Area of emphasis | Hospital’s responsibility | Physician’s responsibility | Patient’s responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a positive environment for care | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ |

| Providing clear communication | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Obtaining informed consent | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Making reasonable requests | 1+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Compliance | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Key to the relative scale: 1+: at the least, minimally responsible; 2+: at the least, somewhat responsible; 3+, responsible to the greatest degree. | |||

The importance of the intake form

At the outset of OB care, in most practices, the patient provides the initial detailed medical history by completing a form in the waiting room. In reviewing and completing this survey with her during the appointment, pay particular attention to those questions for which the response has been left blank.

Patients need to understand that key recommendations about their care, and a proper analysis of their concerns, are based on the information that they provide on this survey. In our practices, we find that patients answer most of these early questions without difficulty—even inquiries of a personal nature, such as the number of prior pregnancies, or drug, alcohol, and smoking habits—as long as they understand why it’s in their best interests for you to have this information. If they leave a question blank and you do not follow up verbally, you may have lost invaluable information that can affect the outcome of her pregnancy.

What should you do when, occasionally, a patient refuses to answer one of your questions? We recommend that you record her refusal on the form itself, where the note remains part of the record.

Keep in mind that all necessary and useful information about a patient may not be available, or may not be appropriate to consider, at the initial prenatal visit. In that case, you have an ongoing opportunity—at subsequent visits during the pregnancy—to develop her full medical profile and algorithm.

The necessity of adherence

It almost goes without saying: To provide the care that our patients need, we sometimes require the unpleasant of them—to undergo evaluations, or testing, or to take medications that may be inconvenient or costly.

After you explain the specific course of care to a patient—whether you’re ordering a test or writing a prescription—your follow-up must include notation in the record of adherence. The fact is that both of you share responsibility for having her understand the importance of adherence to your instructions and the consequences of limited adherence or nonadherence.

Recall one of the lessons from the case that introduced this article: For the patient to make an informed decision about her care, the clinician must have thorough knowledge of 1) the risks and benefits of whatever intervention is being proposed in the particular clinical scenario and 2) the available alternatives. It is key that you communicate your risk-benefit assessment accurately to the patient.

Follow-up

Sometimes, new medical problems arise during subsequent prenatal visits. Follow-up appointments also provide an opportunity for you to expand your attention to problems identified earlier. Regardless of what the patient reported about her history and current health at the initial prenatal visit, listen for her to bring new issues to light for resolution later in the pregnancy that will have an impact on L & D. Again, it goes without saying but needs to be said: The OB clinician needs to have whatever skills are necessary to 1) fully evaluate the progress of a pregnancy and 2) make recommendations for care in light of changes in the status of mother and fetus along the way.

TABLE 4 Examples of the cardinal rule of “Be specific”

when you document care

| Instead of noting … | … Use alternative wording |

|---|---|

| “Mild vaginal bleeding” | “Vaginal bleeding requiring two pads an hour” |

| “Gentle traction” | “The shoulders were rotated before assisting the patient’s expulsive efforts” |

| “Patient refuses…” [or “declines…”] | “Patient voiced the nature of the problem and the alternatives that i have explained to her” |

| “Expedited cesarean section” | “The time from decision to incision was 35 minutes” |

Basic principles of documentation

The medical record is the best witness to interactions between a physician and a patient. In the record, we’re required to write a “5-C” description of events—namely, one that is:

- correct

- comprehensive

- conscientious

- clear

- contemporaneous.

Avoid medical jargon in the record. Be careful not to use vague terminology or descriptions, such as “mild vaginal bleeding,” “gentle traction,” or “patient refuses and accepts the consequences.” Specificity is the key to accuracy with respect to documentation (TABLE 4).

Editor’s note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the January 2011 issue of OBG Management. The authors’ analysis of L & D malpractice claims moves to a discussion of causation—by way of 4 troubling cases.

You’ll find a rich, useful archive of expert analysis of your professional liability and malpractice risk, at www.obgmanagement.com

• 10 keys to defending (or, better, keeping clear of) a shoulder dystocia suit

Andrew K. Worek, Esq (March 2008)

• After a patient’s unexpected death, First Aid for the emotionally wounded

Ronald A. Chez, MD, and Wayne Fortin, MS (April 2010)

• Afraid of getting sued? A plaintiff attorney offers counsel (but no sympathy)

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lewis Laska, JD, PhD (October 2009)

• Can a change in practice patterns reduce the number of OB malpractice claims?

Jason K. Baxter, MD, MSCP, and Louis Weinstein, MD (April 2009)

• Strategies for breaking bad news to patients

Barry Bub, MD (September 2008)

• Stuff of nightmares: Criminal prosecution for malpractice

Gary Steinman, MD, PhD (August 2008)

• Deposition Dos and Don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions

James L. Knoll, IV, MD, and Phillip J. Resnick, MD (May 2008)

• Playing high-stakes poker: Do you fight—or settle—that malpractice lawsuit?

Jeffrey Segal, MD (April 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based labor and delivery management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):445-454.

2. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980-986.

3. Huvane K. Health literacy: reading is just the beginning. Focus on multicultural healthcare. 2007;3(4):16-19.

4. Giordano K. Legal Principles. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello L, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

5. The Four Elements of Medical Malpractice Yale New Haven Medical Center: Issues in Risk Management. 1997.

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.

Recognize the benefits of partnership

Forging a partnership with the patient:

- improves the accuracy of information

- eases ongoing communication

- facilitates informed consent

- provides an opportunity for you to educate her.

TABLE 2 When building trust, both patient and physician

are charged with responsibilities

| In regard to … | The patient’s responsibility is to … | The physician’s responsibility is to … |

|---|---|---|

| Gathering an honest and complete medical history | Know and report | Question completely |

| Being adherent to prescribed care | Follow through | Make reasonable demands |

| Making decisions about care | Ask questions and actively participate in choices Make realistic requests | Be knowledgeable about available alternatives Individualize options |

Key concept #3

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Patient and physician both have responsibilities that are important to achieving an optimal outcome; so does the hospital (TABLE 2 and TABLE 3). Both patient and physician should practice full disclosure throughout the course of care; this will benefit both of you.4 Here are a few select examples.

TABLE 3 Relative degrees of responsibility for a good outcome

vary across interested parties, but none are exempt

| Area of emphasis | Hospital’s responsibility | Physician’s responsibility | Patient’s responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a positive environment for care | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ |

| Providing clear communication | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Obtaining informed consent | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Making reasonable requests | 1+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Compliance | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Key to the relative scale: 1+: at the least, minimally responsible; 2+: at the least, somewhat responsible; 3+, responsible to the greatest degree. | |||

The importance of the intake form

At the outset of OB care, in most practices, the patient provides the initial detailed medical history by completing a form in the waiting room. In reviewing and completing this survey with her during the appointment, pay particular attention to those questions for which the response has been left blank.

Patients need to understand that key recommendations about their care, and a proper analysis of their concerns, are based on the information that they provide on this survey. In our practices, we find that patients answer most of these early questions without difficulty—even inquiries of a personal nature, such as the number of prior pregnancies, or drug, alcohol, and smoking habits—as long as they understand why it’s in their best interests for you to have this information. If they leave a question blank and you do not follow up verbally, you may have lost invaluable information that can affect the outcome of her pregnancy.

What should you do when, occasionally, a patient refuses to answer one of your questions? We recommend that you record her refusal on the form itself, where the note remains part of the record.

Keep in mind that all necessary and useful information about a patient may not be available, or may not be appropriate to consider, at the initial prenatal visit. In that case, you have an ongoing opportunity—at subsequent visits during the pregnancy—to develop her full medical profile and algorithm.

The necessity of adherence

It almost goes without saying: To provide the care that our patients need, we sometimes require the unpleasant of them—to undergo evaluations, or testing, or to take medications that may be inconvenient or costly.

After you explain the specific course of care to a patient—whether you’re ordering a test or writing a prescription—your follow-up must include notation in the record of adherence. The fact is that both of you share responsibility for having her understand the importance of adherence to your instructions and the consequences of limited adherence or nonadherence.

Recall one of the lessons from the case that introduced this article: For the patient to make an informed decision about her care, the clinician must have thorough knowledge of 1) the risks and benefits of whatever intervention is being proposed in the particular clinical scenario and 2) the available alternatives. It is key that you communicate your risk-benefit assessment accurately to the patient.

Follow-up

Sometimes, new medical problems arise during subsequent prenatal visits. Follow-up appointments also provide an opportunity for you to expand your attention to problems identified earlier. Regardless of what the patient reported about her history and current health at the initial prenatal visit, listen for her to bring new issues to light for resolution later in the pregnancy that will have an impact on L & D. Again, it goes without saying but needs to be said: The OB clinician needs to have whatever skills are necessary to 1) fully evaluate the progress of a pregnancy and 2) make recommendations for care in light of changes in the status of mother and fetus along the way.

TABLE 4 Examples of the cardinal rule of “Be specific”

when you document care

| Instead of noting … | … Use alternative wording |

|---|---|

| “Mild vaginal bleeding” | “Vaginal bleeding requiring two pads an hour” |

| “Gentle traction” | “The shoulders were rotated before assisting the patient’s expulsive efforts” |

| “Patient refuses…” [or “declines…”] | “Patient voiced the nature of the problem and the alternatives that i have explained to her” |

| “Expedited cesarean section” | “The time from decision to incision was 35 minutes” |

Basic principles of documentation

The medical record is the best witness to interactions between a physician and a patient. In the record, we’re required to write a “5-C” description of events—namely, one that is:

- correct

- comprehensive

- conscientious

- clear

- contemporaneous.

Avoid medical jargon in the record. Be careful not to use vague terminology or descriptions, such as “mild vaginal bleeding,” “gentle traction,” or “patient refuses and accepts the consequences.” Specificity is the key to accuracy with respect to documentation (TABLE 4).

Editor’s note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the January 2011 issue of OBG Management. The authors’ analysis of L & D malpractice claims moves to a discussion of causation—by way of 4 troubling cases.

You’ll find a rich, useful archive of expert analysis of your professional liability and malpractice risk, at www.obgmanagement.com

• 10 keys to defending (or, better, keeping clear of) a shoulder dystocia suit

Andrew K. Worek, Esq (March 2008)

• After a patient’s unexpected death, First Aid for the emotionally wounded

Ronald A. Chez, MD, and Wayne Fortin, MS (April 2010)

• Afraid of getting sued? A plaintiff attorney offers counsel (but no sympathy)

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lewis Laska, JD, PhD (October 2009)

• Can a change in practice patterns reduce the number of OB malpractice claims?

Jason K. Baxter, MD, MSCP, and Louis Weinstein, MD (April 2009)

• Strategies for breaking bad news to patients

Barry Bub, MD (September 2008)

• Stuff of nightmares: Criminal prosecution for malpractice

Gary Steinman, MD, PhD (August 2008)

• Deposition Dos and Don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions

James L. Knoll, IV, MD, and Phillip J. Resnick, MD (May 2008)

• Playing high-stakes poker: Do you fight—or settle—that malpractice lawsuit?

Jeffrey Segal, MD (April 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.

Recognize the benefits of partnership

Forging a partnership with the patient:

- improves the accuracy of information

- eases ongoing communication

- facilitates informed consent

- provides an opportunity for you to educate her.

TABLE 2 When building trust, both patient and physician

are charged with responsibilities

| In regard to … | The patient’s responsibility is to … | The physician’s responsibility is to … |

|---|---|---|

| Gathering an honest and complete medical history | Know and report | Question completely |

| Being adherent to prescribed care | Follow through | Make reasonable demands |

| Making decisions about care | Ask questions and actively participate in choices Make realistic requests | Be knowledgeable about available alternatives Individualize options |

Key concept #3

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Patient and physician both have responsibilities that are important to achieving an optimal outcome; so does the hospital (TABLE 2 and TABLE 3). Both patient and physician should practice full disclosure throughout the course of care; this will benefit both of you.4 Here are a few select examples.

TABLE 3 Relative degrees of responsibility for a good outcome

vary across interested parties, but none are exempt

| Area of emphasis | Hospital’s responsibility | Physician’s responsibility | Patient’s responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a positive environment for care | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ |

| Providing clear communication | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Obtaining informed consent | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Making reasonable requests | 1+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Compliance | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Key to the relative scale: 1+: at the least, minimally responsible; 2+: at the least, somewhat responsible; 3+, responsible to the greatest degree. | |||

The importance of the intake form

At the outset of OB care, in most practices, the patient provides the initial detailed medical history by completing a form in the waiting room. In reviewing and completing this survey with her during the appointment, pay particular attention to those questions for which the response has been left blank.

Patients need to understand that key recommendations about their care, and a proper analysis of their concerns, are based on the information that they provide on this survey. In our practices, we find that patients answer most of these early questions without difficulty—even inquiries of a personal nature, such as the number of prior pregnancies, or drug, alcohol, and smoking habits—as long as they understand why it’s in their best interests for you to have this information. If they leave a question blank and you do not follow up verbally, you may have lost invaluable information that can affect the outcome of her pregnancy.

What should you do when, occasionally, a patient refuses to answer one of your questions? We recommend that you record her refusal on the form itself, where the note remains part of the record.

Keep in mind that all necessary and useful information about a patient may not be available, or may not be appropriate to consider, at the initial prenatal visit. In that case, you have an ongoing opportunity—at subsequent visits during the pregnancy—to develop her full medical profile and algorithm.

The necessity of adherence

It almost goes without saying: To provide the care that our patients need, we sometimes require the unpleasant of them—to undergo evaluations, or testing, or to take medications that may be inconvenient or costly.

After you explain the specific course of care to a patient—whether you’re ordering a test or writing a prescription—your follow-up must include notation in the record of adherence. The fact is that both of you share responsibility for having her understand the importance of adherence to your instructions and the consequences of limited adherence or nonadherence.

Recall one of the lessons from the case that introduced this article: For the patient to make an informed decision about her care, the clinician must have thorough knowledge of 1) the risks and benefits of whatever intervention is being proposed in the particular clinical scenario and 2) the available alternatives. It is key that you communicate your risk-benefit assessment accurately to the patient.

Follow-up

Sometimes, new medical problems arise during subsequent prenatal visits. Follow-up appointments also provide an opportunity for you to expand your attention to problems identified earlier. Regardless of what the patient reported about her history and current health at the initial prenatal visit, listen for her to bring new issues to light for resolution later in the pregnancy that will have an impact on L & D. Again, it goes without saying but needs to be said: The OB clinician needs to have whatever skills are necessary to 1) fully evaluate the progress of a pregnancy and 2) make recommendations for care in light of changes in the status of mother and fetus along the way.

TABLE 4 Examples of the cardinal rule of “Be specific”

when you document care

| Instead of noting … | … Use alternative wording |

|---|---|

| “Mild vaginal bleeding” | “Vaginal bleeding requiring two pads an hour” |

| “Gentle traction” | “The shoulders were rotated before assisting the patient’s expulsive efforts” |

| “Patient refuses…” [or “declines…”] | “Patient voiced the nature of the problem and the alternatives that i have explained to her” |

| “Expedited cesarean section” | “The time from decision to incision was 35 minutes” |

Basic principles of documentation

The medical record is the best witness to interactions between a physician and a patient. In the record, we’re required to write a “5-C” description of events—namely, one that is:

- correct

- comprehensive

- conscientious

- clear

- contemporaneous.

Avoid medical jargon in the record. Be careful not to use vague terminology or descriptions, such as “mild vaginal bleeding,” “gentle traction,” or “patient refuses and accepts the consequences.” Specificity is the key to accuracy with respect to documentation (TABLE 4).

Editor’s note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the January 2011 issue of OBG Management. The authors’ analysis of L & D malpractice claims moves to a discussion of causation—by way of 4 troubling cases.

You’ll find a rich, useful archive of expert analysis of your professional liability and malpractice risk, at www.obgmanagement.com

• 10 keys to defending (or, better, keeping clear of) a shoulder dystocia suit

Andrew K. Worek, Esq (March 2008)

• After a patient’s unexpected death, First Aid for the emotionally wounded

Ronald A. Chez, MD, and Wayne Fortin, MS (April 2010)

• Afraid of getting sued? A plaintiff attorney offers counsel (but no sympathy)

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lewis Laska, JD, PhD (October 2009)

• Can a change in practice patterns reduce the number of OB malpractice claims?

Jason K. Baxter, MD, MSCP, and Louis Weinstein, MD (April 2009)

• Strategies for breaking bad news to patients

Barry Bub, MD (September 2008)

• Stuff of nightmares: Criminal prosecution for malpractice

Gary Steinman, MD, PhD (August 2008)

• Deposition Dos and Don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions

James L. Knoll, IV, MD, and Phillip J. Resnick, MD (May 2008)

• Playing high-stakes poker: Do you fight—or settle—that malpractice lawsuit?

Jeffrey Segal, MD (April 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based labor and delivery management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):445-454.

2. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980-986.

3. Huvane K. Health literacy: reading is just the beginning. Focus on multicultural healthcare. 2007;3(4):16-19.

4. Giordano K. Legal Principles. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello L, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

5. The Four Elements of Medical Malpractice Yale New Haven Medical Center: Issues in Risk Management. 1997.

1. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based labor and delivery management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):445-454.

2. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980-986.

3. Huvane K. Health literacy: reading is just the beginning. Focus on multicultural healthcare. 2007;3(4):16-19.

4. Giordano K. Legal Principles. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello L, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

5. The Four Elements of Medical Malpractice Yale New Haven Medical Center: Issues in Risk Management. 1997.