User login

Empyema is a well-known sequela resulting from the extension of bacterial pneumonia or pulmonary abscess to the pleural space. This case highlights the organism Streptococcus intermedius (S intermedius), an uncommon cause of pulmonary empyema.1Streptococcus intermedius is endogenous among oral flora and is notorious for its abscess-forming capabilities when spread to alternative sites.

The patient was a healthy, active-duty male who presented in sepsis after months of worsening dyspnea and subacute hemoptysis following 2 near-drowning episodes during Special Operations training. Eight weeks after urgent surgical decortication and intensive antibiotic therapy, the patient experienced a complete resolution of his symptoms. A brief discussion follows concerning the pathogenesis and relevant literature regarding S intermedius infections.

Case History

A 21-year-old Air Force Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) trainee with no significant past medical history presented with worsening dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis after failed outpatient therapy with levofloxacin for presumed community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) 3 days prior. The chest X-ray at that time demonstrated a left lower lobe consolidation with no evidence of pleural effusion or pulmonary abscess on the lateral view (Figure 1).

The patient stated that his symptoms started about 3 months prior with fever, chills, and night sweats. His symptoms occurred episodically every few weeks, but he had no knowledge of any significant events preceding the illness. The patient developed intermittent hemoptysis 2 weeks later. This included blood-streaked mucus with productive cough and bright-red blood, ranging between a teaspoon and a tablespoon, according to the patient. The patient gradually developed increased dyspnea, which began to impact his performance during Special Operations physical training. His symptoms gradually progressed to worsening dyspnea, which began to affect daily living activities, and new-onset left-sided rib pain. The patient reported no relevant travel history and tested negative for purified protein derivatives 3 months before the initial presentation.

On further questioning, the patient disclosed 2 near-drowning incidents within the preceding year. The first occurred 10 months before presentation, when the patient was performing a 1-minute underwater swim in preparation for the TACP training. The patient stated that he came to the surface to take a breath and lost consciousness. He was immediately brought to the edge of the pool and quickly recovered with no apparent residual symptoms. The second episode occurred during an underwater buddy-breathing training exercise 4 months before presentation and just 3 weeks before symptom onset. The patient reported that he knew he was not getting enough air but remained underwater, concerned that he might fail the exercise. He had a transient syncopal episode shortly after aspirating and was brought to the surface. Afterward, the patient refused to receive medical attention following this event, fearing risk of medical disqualification from training. He reportedly did not experience symptoms after this second episode.

The patient’s past medical history included seasonal allergic rhinitis, and his past surgical history was unremarkable. The patient was not taking medication other than levofloxacin, prescribed for the suspected CAP. The patient was allergic to penicillin, did not use tobacco, and reported drinking about 5 alcoholic beverages per week. His family history included a sister with asthma and a mother with factor V Leiden deficiency and pulmonary embolism related to hormone replacement therapy.

The patient’s vital signs revealed a temperature of 103.2°F, 114 beats per minute pulse, 24 breaths per minute respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was noted to be in moderate respiratory distress with accessory muscle use and was diaphoretic. Breath sounds were diminished in the left upper and lower lung fields with significant egophony.

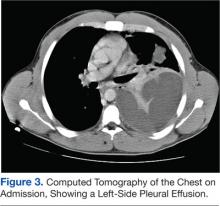

Tests revealed a white blood cell count of 23,300/mm3 with 30% bandemia. A chest radiograph showed an infiltrate/effusion of the entire left hemithorax (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed a large multiloculated left-side pleural effusion (Figure 3).

The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, including intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone, azithromycin, and clindamycin. He underwent thoracentesis on admission, yielding only 300 mL of purulent fluid, confirming its loculated status.

Serum total protein was 7.1 g/dL, and no serum lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) was obtained at the time of thoracentesis. Pleural fluid analysis revealed a protein of 5.2 g/dL, and an LDH of 5,176 units/L, meeting Light’s criteria for exudate based on a pleural fluid protein to serum protein ratio of > 0.5 (0.69) and pleural fluid LDH level > two-thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.

General surgery placed 2 thoracostomy tubes in the left hemithorax without significant drainage. On the first hospital day the patient seemed toxic and underwent a minithoracotomy with decortication. The Gram stain of the blood and blood cultures were negative over 72 hours. Another Gram stain of pleural fluid showed Gram-positive cocci in pairs. Pleural fluid cultures obtained during the procedure revealed S intermedius consistent with the patient’s history of aspiration and abscess formation. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were not performed on the sample.

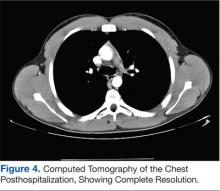

A peripherally inserted central catheter line was placed for daily IV ceftriaxone infusions to be continued with oral clindamycin for the subsequent 4 weeks. A CT scan of the chest at 8 weeks posthospitalization revealed minimal postoperative scarring, and pulmonary function tests showed normal flow volume loop and maximum voluntary ventilation (Figure 4). The patient reported full recovery and was returned to full activity, including further Special Operations training.

Discussion

Pulmonary infections associated with near-drowning events are caused by a host of organisms that must be considered in the differential diagnosis. The most common include Aeromonas species, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Pseudallescheria boydii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.2 However, the causative organism in this case was endogenous. Streptococcus intermedius is an anaerobic, Gram-positive cocci, a member of the Streptococcus milleri group, and is considered normal flora of the oral mucosa, upper respiratory tract, vagina, and gastrointestinal tract.3,4 This organism is innocuous in its normal habitat but may result in considerable mortality and morbidity if spread to alternative sites due to its ability to form abscesses and cause systemic infections.5

Although uncommon, respiratory infections caused by S intermedius typically result from aspiration of gastric or oral contents and may lead to pulmonary abscesses or empyema.1,6,7 It may present as a primary empyema.8 Current literature suggests a mortality rate between 2% and 14% with higher rates in older populations.9 A retrospective study looking at 72 cases of Streptococci viridans pulmonary infection from 1984 to 1996 found only 2 documented cases where S intermedius was identified as the cause of concomitant empyema and lung abscesses. This study also indicated a strong male predominance with only 7% of lung abscesses occurring in females.10,11

This patient developed a pulmonary abscess and empyema as a probable consequence of aspiration during underwater training exercises. The diagnosis was complicated, because the patient did not initially disclose the pertinent history, and he ignored his symptoms so that he could continue training. His actions delayed aggressive antibiotic therapy and likely led to the rapid progression of pneumonia and his complicated clinical course, because S intermedius has shown intermediate susceptibility or resistance to fluoroquinolone monotherapy.12

This case was also unusual given the subacute presentation and 3-month history of hemoptysis. On review of the available medical literature, hemoptysis is an unusual symptom of pulmonary infections caused by S intermedius but can likely be attributed to necrosis of the pulmonary tissue.8,13

Most patients with S intermedius pulmonary infection rapidly progress due to the virulence of this organism and predisposing comorbidities.14,15 However, this patient had a relatively indolent progression for 3 months, which speaks to the increased respiratory reserve of a healthy, young male in excellent cardiovascular condition.

Conclusion

This case highlights the potential for normal oral flora to cause advanced pulmonary disease in patients with no significant comorbidities. Streptococcus intermedius infections can be subacute in presentation but may rapidly progress to severe disease once seeded in the pleural cavity. Whereas early pleural space drainage remains fundamental, urgent surgical intervention may be required for loculated disease. Although infections with this organism may lead to irreversible pulmonary complications, complete resolution with full recovery is possible in young, healthy patients.

Primary care physicians must take a careful history to ensure optimal patient outcomes. This concept is particularly important to consider in aviators and Special Operations personnel who may be reluctant to seek medical care. Establishing a sense of trust among active-duty military is essential for mission accomplishment.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Weightman NC, Barnham MRD, Dove M. Streptococcus milleri group bacteraemia in North Yorkshire, England (1989-2000). Indian J Med Res. 2004;119(suppl):164-167.

2. Ender PT, Dolan MJ. Pneumonia associated with near-drowning. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;1(4):896-907.

3. Porta G, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Gómez L, et al. Thoracic infection caused by Streptococcus milleri. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(2):357-362.

4. Van der Auwera P. Clinical significance of Streptococcus milleri. Eur J Clin Microbiol.1985;4(4):386-390.

5. Murray HW, Gross KC, Masur H, Roberts RB. Serious infections caused by Streptococcus milleri. Am J Med. 1978;64(5):759-764.

6. Shinzato T, Saito A. The Streptococcus milleri group as a cause of pulmonary infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(suppl 3):S238-S243.

7. Frankish PD, Kolbe J. Thoracic empyema due to Streptococcus milleri: Four cases. N Z Med J. 1984;97(769):849-851.

8. Iskandar SB, Al Hasan MA, Roy TM, Byrd RP Jr. Streptococcus intermedius: An unusual cause of a primary empyema. Tenn Med. 2006;99(2):37-39.

9. de Hoyos A, Sundaresan S. Thoracic empyema. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82(3):643-671.

10. Jerng JS, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Lee LN, Yang PC, Luh KT. Empyema thoracis and lung abscess caused by viridans streptococci. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1508-1514.

11. Wargo KA, McConnell VJ, Higginbotham SA. A case of Streptococcus intermedius empyema. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(6):1208-1210.

12. Limia A, Jiménez ML, Alarcón T, López-Brea M. Five-year analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18(6):440-444.

13. Wong CA, Donal F, Macfarlane JT. Streptococcus milleri pulmonary disease: A review and clinical description of 25 patients. Thorax. 1995;50(10):1093-1096.

14. Shlaes DM, Lerner PI, Wolinsky E, Gopalakrishna KV. Infections due to Lancefield F and related Streptococci (S milleri, S anginosus). Medicine (Baltimore). 1981;60(3):197-207.

15. Roy WJ Jr, Roy TM, Davis GJ. Thoracic empyema due to Streptococcus intermedius. J Ky Med Assoc. 1991;89(11):558-562.

Empyema is a well-known sequela resulting from the extension of bacterial pneumonia or pulmonary abscess to the pleural space. This case highlights the organism Streptococcus intermedius (S intermedius), an uncommon cause of pulmonary empyema.1Streptococcus intermedius is endogenous among oral flora and is notorious for its abscess-forming capabilities when spread to alternative sites.

The patient was a healthy, active-duty male who presented in sepsis after months of worsening dyspnea and subacute hemoptysis following 2 near-drowning episodes during Special Operations training. Eight weeks after urgent surgical decortication and intensive antibiotic therapy, the patient experienced a complete resolution of his symptoms. A brief discussion follows concerning the pathogenesis and relevant literature regarding S intermedius infections.

Case History

A 21-year-old Air Force Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) trainee with no significant past medical history presented with worsening dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis after failed outpatient therapy with levofloxacin for presumed community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) 3 days prior. The chest X-ray at that time demonstrated a left lower lobe consolidation with no evidence of pleural effusion or pulmonary abscess on the lateral view (Figure 1).

The patient stated that his symptoms started about 3 months prior with fever, chills, and night sweats. His symptoms occurred episodically every few weeks, but he had no knowledge of any significant events preceding the illness. The patient developed intermittent hemoptysis 2 weeks later. This included blood-streaked mucus with productive cough and bright-red blood, ranging between a teaspoon and a tablespoon, according to the patient. The patient gradually developed increased dyspnea, which began to impact his performance during Special Operations physical training. His symptoms gradually progressed to worsening dyspnea, which began to affect daily living activities, and new-onset left-sided rib pain. The patient reported no relevant travel history and tested negative for purified protein derivatives 3 months before the initial presentation.

On further questioning, the patient disclosed 2 near-drowning incidents within the preceding year. The first occurred 10 months before presentation, when the patient was performing a 1-minute underwater swim in preparation for the TACP training. The patient stated that he came to the surface to take a breath and lost consciousness. He was immediately brought to the edge of the pool and quickly recovered with no apparent residual symptoms. The second episode occurred during an underwater buddy-breathing training exercise 4 months before presentation and just 3 weeks before symptom onset. The patient reported that he knew he was not getting enough air but remained underwater, concerned that he might fail the exercise. He had a transient syncopal episode shortly after aspirating and was brought to the surface. Afterward, the patient refused to receive medical attention following this event, fearing risk of medical disqualification from training. He reportedly did not experience symptoms after this second episode.

The patient’s past medical history included seasonal allergic rhinitis, and his past surgical history was unremarkable. The patient was not taking medication other than levofloxacin, prescribed for the suspected CAP. The patient was allergic to penicillin, did not use tobacco, and reported drinking about 5 alcoholic beverages per week. His family history included a sister with asthma and a mother with factor V Leiden deficiency and pulmonary embolism related to hormone replacement therapy.

The patient’s vital signs revealed a temperature of 103.2°F, 114 beats per minute pulse, 24 breaths per minute respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was noted to be in moderate respiratory distress with accessory muscle use and was diaphoretic. Breath sounds were diminished in the left upper and lower lung fields with significant egophony.

Tests revealed a white blood cell count of 23,300/mm3 with 30% bandemia. A chest radiograph showed an infiltrate/effusion of the entire left hemithorax (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed a large multiloculated left-side pleural effusion (Figure 3).

The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, including intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone, azithromycin, and clindamycin. He underwent thoracentesis on admission, yielding only 300 mL of purulent fluid, confirming its loculated status.

Serum total protein was 7.1 g/dL, and no serum lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) was obtained at the time of thoracentesis. Pleural fluid analysis revealed a protein of 5.2 g/dL, and an LDH of 5,176 units/L, meeting Light’s criteria for exudate based on a pleural fluid protein to serum protein ratio of > 0.5 (0.69) and pleural fluid LDH level > two-thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.

General surgery placed 2 thoracostomy tubes in the left hemithorax without significant drainage. On the first hospital day the patient seemed toxic and underwent a minithoracotomy with decortication. The Gram stain of the blood and blood cultures were negative over 72 hours. Another Gram stain of pleural fluid showed Gram-positive cocci in pairs. Pleural fluid cultures obtained during the procedure revealed S intermedius consistent with the patient’s history of aspiration and abscess formation. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were not performed on the sample.

A peripherally inserted central catheter line was placed for daily IV ceftriaxone infusions to be continued with oral clindamycin for the subsequent 4 weeks. A CT scan of the chest at 8 weeks posthospitalization revealed minimal postoperative scarring, and pulmonary function tests showed normal flow volume loop and maximum voluntary ventilation (Figure 4). The patient reported full recovery and was returned to full activity, including further Special Operations training.

Discussion

Pulmonary infections associated with near-drowning events are caused by a host of organisms that must be considered in the differential diagnosis. The most common include Aeromonas species, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Pseudallescheria boydii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.2 However, the causative organism in this case was endogenous. Streptococcus intermedius is an anaerobic, Gram-positive cocci, a member of the Streptococcus milleri group, and is considered normal flora of the oral mucosa, upper respiratory tract, vagina, and gastrointestinal tract.3,4 This organism is innocuous in its normal habitat but may result in considerable mortality and morbidity if spread to alternative sites due to its ability to form abscesses and cause systemic infections.5

Although uncommon, respiratory infections caused by S intermedius typically result from aspiration of gastric or oral contents and may lead to pulmonary abscesses or empyema.1,6,7 It may present as a primary empyema.8 Current literature suggests a mortality rate between 2% and 14% with higher rates in older populations.9 A retrospective study looking at 72 cases of Streptococci viridans pulmonary infection from 1984 to 1996 found only 2 documented cases where S intermedius was identified as the cause of concomitant empyema and lung abscesses. This study also indicated a strong male predominance with only 7% of lung abscesses occurring in females.10,11

This patient developed a pulmonary abscess and empyema as a probable consequence of aspiration during underwater training exercises. The diagnosis was complicated, because the patient did not initially disclose the pertinent history, and he ignored his symptoms so that he could continue training. His actions delayed aggressive antibiotic therapy and likely led to the rapid progression of pneumonia and his complicated clinical course, because S intermedius has shown intermediate susceptibility or resistance to fluoroquinolone monotherapy.12

This case was also unusual given the subacute presentation and 3-month history of hemoptysis. On review of the available medical literature, hemoptysis is an unusual symptom of pulmonary infections caused by S intermedius but can likely be attributed to necrosis of the pulmonary tissue.8,13

Most patients with S intermedius pulmonary infection rapidly progress due to the virulence of this organism and predisposing comorbidities.14,15 However, this patient had a relatively indolent progression for 3 months, which speaks to the increased respiratory reserve of a healthy, young male in excellent cardiovascular condition.

Conclusion

This case highlights the potential for normal oral flora to cause advanced pulmonary disease in patients with no significant comorbidities. Streptococcus intermedius infections can be subacute in presentation but may rapidly progress to severe disease once seeded in the pleural cavity. Whereas early pleural space drainage remains fundamental, urgent surgical intervention may be required for loculated disease. Although infections with this organism may lead to irreversible pulmonary complications, complete resolution with full recovery is possible in young, healthy patients.

Primary care physicians must take a careful history to ensure optimal patient outcomes. This concept is particularly important to consider in aviators and Special Operations personnel who may be reluctant to seek medical care. Establishing a sense of trust among active-duty military is essential for mission accomplishment.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Empyema is a well-known sequela resulting from the extension of bacterial pneumonia or pulmonary abscess to the pleural space. This case highlights the organism Streptococcus intermedius (S intermedius), an uncommon cause of pulmonary empyema.1Streptococcus intermedius is endogenous among oral flora and is notorious for its abscess-forming capabilities when spread to alternative sites.

The patient was a healthy, active-duty male who presented in sepsis after months of worsening dyspnea and subacute hemoptysis following 2 near-drowning episodes during Special Operations training. Eight weeks after urgent surgical decortication and intensive antibiotic therapy, the patient experienced a complete resolution of his symptoms. A brief discussion follows concerning the pathogenesis and relevant literature regarding S intermedius infections.

Case History

A 21-year-old Air Force Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) trainee with no significant past medical history presented with worsening dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis after failed outpatient therapy with levofloxacin for presumed community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) 3 days prior. The chest X-ray at that time demonstrated a left lower lobe consolidation with no evidence of pleural effusion or pulmonary abscess on the lateral view (Figure 1).

The patient stated that his symptoms started about 3 months prior with fever, chills, and night sweats. His symptoms occurred episodically every few weeks, but he had no knowledge of any significant events preceding the illness. The patient developed intermittent hemoptysis 2 weeks later. This included blood-streaked mucus with productive cough and bright-red blood, ranging between a teaspoon and a tablespoon, according to the patient. The patient gradually developed increased dyspnea, which began to impact his performance during Special Operations physical training. His symptoms gradually progressed to worsening dyspnea, which began to affect daily living activities, and new-onset left-sided rib pain. The patient reported no relevant travel history and tested negative for purified protein derivatives 3 months before the initial presentation.

On further questioning, the patient disclosed 2 near-drowning incidents within the preceding year. The first occurred 10 months before presentation, when the patient was performing a 1-minute underwater swim in preparation for the TACP training. The patient stated that he came to the surface to take a breath and lost consciousness. He was immediately brought to the edge of the pool and quickly recovered with no apparent residual symptoms. The second episode occurred during an underwater buddy-breathing training exercise 4 months before presentation and just 3 weeks before symptom onset. The patient reported that he knew he was not getting enough air but remained underwater, concerned that he might fail the exercise. He had a transient syncopal episode shortly after aspirating and was brought to the surface. Afterward, the patient refused to receive medical attention following this event, fearing risk of medical disqualification from training. He reportedly did not experience symptoms after this second episode.

The patient’s past medical history included seasonal allergic rhinitis, and his past surgical history was unremarkable. The patient was not taking medication other than levofloxacin, prescribed for the suspected CAP. The patient was allergic to penicillin, did not use tobacco, and reported drinking about 5 alcoholic beverages per week. His family history included a sister with asthma and a mother with factor V Leiden deficiency and pulmonary embolism related to hormone replacement therapy.

The patient’s vital signs revealed a temperature of 103.2°F, 114 beats per minute pulse, 24 breaths per minute respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was noted to be in moderate respiratory distress with accessory muscle use and was diaphoretic. Breath sounds were diminished in the left upper and lower lung fields with significant egophony.

Tests revealed a white blood cell count of 23,300/mm3 with 30% bandemia. A chest radiograph showed an infiltrate/effusion of the entire left hemithorax (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed a large multiloculated left-side pleural effusion (Figure 3).

The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, including intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone, azithromycin, and clindamycin. He underwent thoracentesis on admission, yielding only 300 mL of purulent fluid, confirming its loculated status.

Serum total protein was 7.1 g/dL, and no serum lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) was obtained at the time of thoracentesis. Pleural fluid analysis revealed a protein of 5.2 g/dL, and an LDH of 5,176 units/L, meeting Light’s criteria for exudate based on a pleural fluid protein to serum protein ratio of > 0.5 (0.69) and pleural fluid LDH level > two-thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.

General surgery placed 2 thoracostomy tubes in the left hemithorax without significant drainage. On the first hospital day the patient seemed toxic and underwent a minithoracotomy with decortication. The Gram stain of the blood and blood cultures were negative over 72 hours. Another Gram stain of pleural fluid showed Gram-positive cocci in pairs. Pleural fluid cultures obtained during the procedure revealed S intermedius consistent with the patient’s history of aspiration and abscess formation. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were not performed on the sample.

A peripherally inserted central catheter line was placed for daily IV ceftriaxone infusions to be continued with oral clindamycin for the subsequent 4 weeks. A CT scan of the chest at 8 weeks posthospitalization revealed minimal postoperative scarring, and pulmonary function tests showed normal flow volume loop and maximum voluntary ventilation (Figure 4). The patient reported full recovery and was returned to full activity, including further Special Operations training.

Discussion

Pulmonary infections associated with near-drowning events are caused by a host of organisms that must be considered in the differential diagnosis. The most common include Aeromonas species, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Pseudallescheria boydii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.2 However, the causative organism in this case was endogenous. Streptococcus intermedius is an anaerobic, Gram-positive cocci, a member of the Streptococcus milleri group, and is considered normal flora of the oral mucosa, upper respiratory tract, vagina, and gastrointestinal tract.3,4 This organism is innocuous in its normal habitat but may result in considerable mortality and morbidity if spread to alternative sites due to its ability to form abscesses and cause systemic infections.5

Although uncommon, respiratory infections caused by S intermedius typically result from aspiration of gastric or oral contents and may lead to pulmonary abscesses or empyema.1,6,7 It may present as a primary empyema.8 Current literature suggests a mortality rate between 2% and 14% with higher rates in older populations.9 A retrospective study looking at 72 cases of Streptococci viridans pulmonary infection from 1984 to 1996 found only 2 documented cases where S intermedius was identified as the cause of concomitant empyema and lung abscesses. This study also indicated a strong male predominance with only 7% of lung abscesses occurring in females.10,11

This patient developed a pulmonary abscess and empyema as a probable consequence of aspiration during underwater training exercises. The diagnosis was complicated, because the patient did not initially disclose the pertinent history, and he ignored his symptoms so that he could continue training. His actions delayed aggressive antibiotic therapy and likely led to the rapid progression of pneumonia and his complicated clinical course, because S intermedius has shown intermediate susceptibility or resistance to fluoroquinolone monotherapy.12

This case was also unusual given the subacute presentation and 3-month history of hemoptysis. On review of the available medical literature, hemoptysis is an unusual symptom of pulmonary infections caused by S intermedius but can likely be attributed to necrosis of the pulmonary tissue.8,13

Most patients with S intermedius pulmonary infection rapidly progress due to the virulence of this organism and predisposing comorbidities.14,15 However, this patient had a relatively indolent progression for 3 months, which speaks to the increased respiratory reserve of a healthy, young male in excellent cardiovascular condition.

Conclusion

This case highlights the potential for normal oral flora to cause advanced pulmonary disease in patients with no significant comorbidities. Streptococcus intermedius infections can be subacute in presentation but may rapidly progress to severe disease once seeded in the pleural cavity. Whereas early pleural space drainage remains fundamental, urgent surgical intervention may be required for loculated disease. Although infections with this organism may lead to irreversible pulmonary complications, complete resolution with full recovery is possible in young, healthy patients.

Primary care physicians must take a careful history to ensure optimal patient outcomes. This concept is particularly important to consider in aviators and Special Operations personnel who may be reluctant to seek medical care. Establishing a sense of trust among active-duty military is essential for mission accomplishment.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Weightman NC, Barnham MRD, Dove M. Streptococcus milleri group bacteraemia in North Yorkshire, England (1989-2000). Indian J Med Res. 2004;119(suppl):164-167.

2. Ender PT, Dolan MJ. Pneumonia associated with near-drowning. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;1(4):896-907.

3. Porta G, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Gómez L, et al. Thoracic infection caused by Streptococcus milleri. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(2):357-362.

4. Van der Auwera P. Clinical significance of Streptococcus milleri. Eur J Clin Microbiol.1985;4(4):386-390.

5. Murray HW, Gross KC, Masur H, Roberts RB. Serious infections caused by Streptococcus milleri. Am J Med. 1978;64(5):759-764.

6. Shinzato T, Saito A. The Streptococcus milleri group as a cause of pulmonary infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(suppl 3):S238-S243.

7. Frankish PD, Kolbe J. Thoracic empyema due to Streptococcus milleri: Four cases. N Z Med J. 1984;97(769):849-851.

8. Iskandar SB, Al Hasan MA, Roy TM, Byrd RP Jr. Streptococcus intermedius: An unusual cause of a primary empyema. Tenn Med. 2006;99(2):37-39.

9. de Hoyos A, Sundaresan S. Thoracic empyema. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82(3):643-671.

10. Jerng JS, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Lee LN, Yang PC, Luh KT. Empyema thoracis and lung abscess caused by viridans streptococci. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1508-1514.

11. Wargo KA, McConnell VJ, Higginbotham SA. A case of Streptococcus intermedius empyema. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(6):1208-1210.

12. Limia A, Jiménez ML, Alarcón T, López-Brea M. Five-year analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18(6):440-444.

13. Wong CA, Donal F, Macfarlane JT. Streptococcus milleri pulmonary disease: A review and clinical description of 25 patients. Thorax. 1995;50(10):1093-1096.

14. Shlaes DM, Lerner PI, Wolinsky E, Gopalakrishna KV. Infections due to Lancefield F and related Streptococci (S milleri, S anginosus). Medicine (Baltimore). 1981;60(3):197-207.

15. Roy WJ Jr, Roy TM, Davis GJ. Thoracic empyema due to Streptococcus intermedius. J Ky Med Assoc. 1991;89(11):558-562.

1. Weightman NC, Barnham MRD, Dove M. Streptococcus milleri group bacteraemia in North Yorkshire, England (1989-2000). Indian J Med Res. 2004;119(suppl):164-167.

2. Ender PT, Dolan MJ. Pneumonia associated with near-drowning. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;1(4):896-907.

3. Porta G, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Gómez L, et al. Thoracic infection caused by Streptococcus milleri. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(2):357-362.

4. Van der Auwera P. Clinical significance of Streptococcus milleri. Eur J Clin Microbiol.1985;4(4):386-390.

5. Murray HW, Gross KC, Masur H, Roberts RB. Serious infections caused by Streptococcus milleri. Am J Med. 1978;64(5):759-764.

6. Shinzato T, Saito A. The Streptococcus milleri group as a cause of pulmonary infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(suppl 3):S238-S243.

7. Frankish PD, Kolbe J. Thoracic empyema due to Streptococcus milleri: Four cases. N Z Med J. 1984;97(769):849-851.

8. Iskandar SB, Al Hasan MA, Roy TM, Byrd RP Jr. Streptococcus intermedius: An unusual cause of a primary empyema. Tenn Med. 2006;99(2):37-39.

9. de Hoyos A, Sundaresan S. Thoracic empyema. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82(3):643-671.

10. Jerng JS, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Lee LN, Yang PC, Luh KT. Empyema thoracis and lung abscess caused by viridans streptococci. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1508-1514.

11. Wargo KA, McConnell VJ, Higginbotham SA. A case of Streptococcus intermedius empyema. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(6):1208-1210.

12. Limia A, Jiménez ML, Alarcón T, López-Brea M. Five-year analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18(6):440-444.

13. Wong CA, Donal F, Macfarlane JT. Streptococcus milleri pulmonary disease: A review and clinical description of 25 patients. Thorax. 1995;50(10):1093-1096.

14. Shlaes DM, Lerner PI, Wolinsky E, Gopalakrishna KV. Infections due to Lancefield F and related Streptococci (S milleri, S anginosus). Medicine (Baltimore). 1981;60(3):197-207.

15. Roy WJ Jr, Roy TM, Davis GJ. Thoracic empyema due to Streptococcus intermedius. J Ky Med Assoc. 1991;89(11):558-562.