User login

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

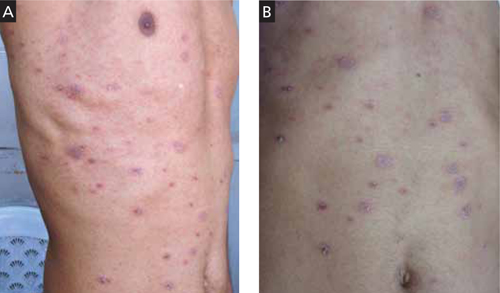

A 35-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic for treatment of a slightly pruritic rash that had begun as a singular, annular erythematous plaque at the sixth intercostal space. The initial plaque erupted around the time he’d had a cold, with fever.

The present rash involved several similar, but smaller, eruptions on the anterior trunk and flank region (FIGURE 1A). Each lesion was surrounded by erythema and collarette scaling. The pattern of the secondary lesions ran parallel to the lines of cleavage. When looking at the patient head on, the pattern resembled a Christmas tree (FIGURE 1B).

The posterior trunk showed similar, but fewer, eruptions. The patient’s palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 1

Scaly plaques and papules

This 35-year-old patient had plaques and papules with collarette scales that followed the lines of cleavage (A) and formed a Christmas tree pattern (B).

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rosea

This patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rosea based on the clinical presentation.

Pityriasis rosea is a common erythematous and scaly disease that typically starts as a “herald patch” and later spreads as generalized eruptions on the trunk and extremities (secondary eruptions). The herald patch is a large lesion with an oval or round shape. Secondary lesions always occupy lines of cleavage (Langer’s lines), giving the eruptions a characteristic Christmas tree appearance. Some patients may exhibit significant pruritus. Both the herald patch and secondary eruptions show collarette scales, a hallmark of pityriasis rosea.1-3

A viral cause

The etiology of pityriasis rosea is uncertain and is most likely viral, possibly caused by human herpesvirus (HHV-6, -7, or -8).2,3 However, other viruses may also play a role. Also, the incidence of pityriasis rosea rises during the cold weather months.4,5

Immune dysregulation? Pityriasis rosea may be a presenting feature of immune dysregulation in patients with HIV infection or systemic malignancy. It may also occur with increasing frequency in those receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs, pregnant women, and patients with diabetes.2,3

Resolves on its own. Pityriasis rosea is generally self-limiting—without any systemic complications—and resolves within 2 to 8 weeks of the appearance of the initial lesion.

Differential includes dermatophytosis and psoriasis

Pityriasis rosea must be differentiated from dermatophytosis, secondary syphilis, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, erythema annulare centrifugum, and pityriasis rosea-like drug eruptions.1-3,6

Dermatophytosis presents as an annular lesion with central clearing and a peripheral papulovesicular border. Patients will complain that the lesions are itchy. Skin scrapings for potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation reveal fungus under light microscope. (Lab tests do not aid in the diagnosis of pityriasis rosea.)

Secondary syphilis should be suspected in patients with a history of genital ulcers. Patients will have generalized lymphadenopathy and a dusky erythematous papulosquamous rash that involves the palms, soles, and mucosa. A venereal disease research laboratory test will be positive.

Psoriasis involves scaly plaques, typically on the knees, elbows, and scalp. The scales are silvery white and leave minute bleeding points on gentle scraping (Auspitz’s sign). Unlike pityriasis rosea, nail changes are often seen in psoriasis. These changes include pitting on the nail plate, onycholysis, oil drop sign, and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica may mimic pityriasis rosea in distribution, but there are no collarette scales. Also, pityriasis lichenoides chronica does not self-resolve; it requires treatment.

Erythema annulare centrifugum is usually a single large erythematous plaque that slowly expands. There is often a history of a tick bite, and no Christmas tree distribution.

Provide symptomatic Tx

Symptomatic treatment of pityriasis rosea is generally adequate, and includes topical emollients, such as white petrolatum or mid-potency steroid creams and antihistamines for pruritus6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Erythromycin. In one study, erythromycin 250 mg QID for 2 weeks hastened the resolution of pityriasis rosea6 (SOR: B). It was suggested that the anti-inflammatory properties and immune modulation of the drug, rather than its antibiotic effect, may have aided the clinical resolution. However, such efficacy was not substantiated in subsequent trials with erythromycin or another macrolide, azithromycin.7-10

High-dose acyclovir. Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day has been shown to reduce disease severity and duration in some patients with pityriasis rosea.11 However, it is not recommended as first-line therapy2 (SOR: C).

Systemic steroids should be avoided in pityriasis rosea, as they may worsen the disease.6

Is the patient of school age? If so, the evidence suggests that he or she should not be kept out of school.6

My patient

I treated this patient with a topical mid-potency steroid (betamethasone dipropionate) twice daily on the affected areas and an oral antihistamine once daily for 10 days. The patient’s symptoms and skin lesions resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Vijay Zawar, MD, DNB, DVD, FAAD, Skin Diseases Center, 21 Shreeram Sankul, Opp. Hotel Panchavati, Vakilwadi Nashik-422001, Maharashtra, India; vijayzawar@yahoo.com

1. Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303-318.

2. Chuh A, Lee A, Zawar V, et al. Pityriasis rosea—an update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:311-315.

3. González LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757-764.

4. Zawar V, Jerajani H, Pol R. Current trends in pityriasis rosea. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2010;5:325-333.

5. Sharma L, Shrivastava K. Clinico-epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:647-649.

6. Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005068.-

7. Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, et al. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:241-244.

8. Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:35-38.

9. Bukhari IA. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:625.-

10. Amer A, Fischer H. Azithromycin does not cure pityriasis rosea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1702-1705.

11. Drago F, Vecchio F, Rebora A. Use of high-dose acyclovir in pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:82-85.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

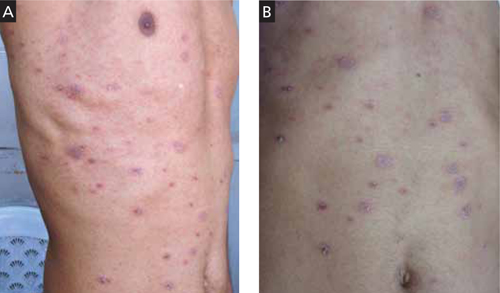

A 35-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic for treatment of a slightly pruritic rash that had begun as a singular, annular erythematous plaque at the sixth intercostal space. The initial plaque erupted around the time he’d had a cold, with fever.

The present rash involved several similar, but smaller, eruptions on the anterior trunk and flank region (FIGURE 1A). Each lesion was surrounded by erythema and collarette scaling. The pattern of the secondary lesions ran parallel to the lines of cleavage. When looking at the patient head on, the pattern resembled a Christmas tree (FIGURE 1B).

The posterior trunk showed similar, but fewer, eruptions. The patient’s palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 1

Scaly plaques and papules

This 35-year-old patient had plaques and papules with collarette scales that followed the lines of cleavage (A) and formed a Christmas tree pattern (B).

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rosea

This patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rosea based on the clinical presentation.

Pityriasis rosea is a common erythematous and scaly disease that typically starts as a “herald patch” and later spreads as generalized eruptions on the trunk and extremities (secondary eruptions). The herald patch is a large lesion with an oval or round shape. Secondary lesions always occupy lines of cleavage (Langer’s lines), giving the eruptions a characteristic Christmas tree appearance. Some patients may exhibit significant pruritus. Both the herald patch and secondary eruptions show collarette scales, a hallmark of pityriasis rosea.1-3

A viral cause

The etiology of pityriasis rosea is uncertain and is most likely viral, possibly caused by human herpesvirus (HHV-6, -7, or -8).2,3 However, other viruses may also play a role. Also, the incidence of pityriasis rosea rises during the cold weather months.4,5

Immune dysregulation? Pityriasis rosea may be a presenting feature of immune dysregulation in patients with HIV infection or systemic malignancy. It may also occur with increasing frequency in those receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs, pregnant women, and patients with diabetes.2,3

Resolves on its own. Pityriasis rosea is generally self-limiting—without any systemic complications—and resolves within 2 to 8 weeks of the appearance of the initial lesion.

Differential includes dermatophytosis and psoriasis

Pityriasis rosea must be differentiated from dermatophytosis, secondary syphilis, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, erythema annulare centrifugum, and pityriasis rosea-like drug eruptions.1-3,6

Dermatophytosis presents as an annular lesion with central clearing and a peripheral papulovesicular border. Patients will complain that the lesions are itchy. Skin scrapings for potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation reveal fungus under light microscope. (Lab tests do not aid in the diagnosis of pityriasis rosea.)

Secondary syphilis should be suspected in patients with a history of genital ulcers. Patients will have generalized lymphadenopathy and a dusky erythematous papulosquamous rash that involves the palms, soles, and mucosa. A venereal disease research laboratory test will be positive.

Psoriasis involves scaly plaques, typically on the knees, elbows, and scalp. The scales are silvery white and leave minute bleeding points on gentle scraping (Auspitz’s sign). Unlike pityriasis rosea, nail changes are often seen in psoriasis. These changes include pitting on the nail plate, onycholysis, oil drop sign, and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica may mimic pityriasis rosea in distribution, but there are no collarette scales. Also, pityriasis lichenoides chronica does not self-resolve; it requires treatment.

Erythema annulare centrifugum is usually a single large erythematous plaque that slowly expands. There is often a history of a tick bite, and no Christmas tree distribution.

Provide symptomatic Tx

Symptomatic treatment of pityriasis rosea is generally adequate, and includes topical emollients, such as white petrolatum or mid-potency steroid creams and antihistamines for pruritus6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Erythromycin. In one study, erythromycin 250 mg QID for 2 weeks hastened the resolution of pityriasis rosea6 (SOR: B). It was suggested that the anti-inflammatory properties and immune modulation of the drug, rather than its antibiotic effect, may have aided the clinical resolution. However, such efficacy was not substantiated in subsequent trials with erythromycin or another macrolide, azithromycin.7-10

High-dose acyclovir. Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day has been shown to reduce disease severity and duration in some patients with pityriasis rosea.11 However, it is not recommended as first-line therapy2 (SOR: C).

Systemic steroids should be avoided in pityriasis rosea, as they may worsen the disease.6

Is the patient of school age? If so, the evidence suggests that he or she should not be kept out of school.6

My patient

I treated this patient with a topical mid-potency steroid (betamethasone dipropionate) twice daily on the affected areas and an oral antihistamine once daily for 10 days. The patient’s symptoms and skin lesions resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Vijay Zawar, MD, DNB, DVD, FAAD, Skin Diseases Center, 21 Shreeram Sankul, Opp. Hotel Panchavati, Vakilwadi Nashik-422001, Maharashtra, India; vijayzawar@yahoo.com

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

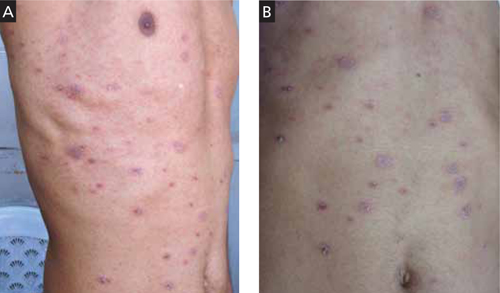

A 35-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic for treatment of a slightly pruritic rash that had begun as a singular, annular erythematous plaque at the sixth intercostal space. The initial plaque erupted around the time he’d had a cold, with fever.

The present rash involved several similar, but smaller, eruptions on the anterior trunk and flank region (FIGURE 1A). Each lesion was surrounded by erythema and collarette scaling. The pattern of the secondary lesions ran parallel to the lines of cleavage. When looking at the patient head on, the pattern resembled a Christmas tree (FIGURE 1B).

The posterior trunk showed similar, but fewer, eruptions. The patient’s palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 1

Scaly plaques and papules

This 35-year-old patient had plaques and papules with collarette scales that followed the lines of cleavage (A) and formed a Christmas tree pattern (B).

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rosea

This patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rosea based on the clinical presentation.

Pityriasis rosea is a common erythematous and scaly disease that typically starts as a “herald patch” and later spreads as generalized eruptions on the trunk and extremities (secondary eruptions). The herald patch is a large lesion with an oval or round shape. Secondary lesions always occupy lines of cleavage (Langer’s lines), giving the eruptions a characteristic Christmas tree appearance. Some patients may exhibit significant pruritus. Both the herald patch and secondary eruptions show collarette scales, a hallmark of pityriasis rosea.1-3

A viral cause

The etiology of pityriasis rosea is uncertain and is most likely viral, possibly caused by human herpesvirus (HHV-6, -7, or -8).2,3 However, other viruses may also play a role. Also, the incidence of pityriasis rosea rises during the cold weather months.4,5

Immune dysregulation? Pityriasis rosea may be a presenting feature of immune dysregulation in patients with HIV infection or systemic malignancy. It may also occur with increasing frequency in those receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs, pregnant women, and patients with diabetes.2,3

Resolves on its own. Pityriasis rosea is generally self-limiting—without any systemic complications—and resolves within 2 to 8 weeks of the appearance of the initial lesion.

Differential includes dermatophytosis and psoriasis

Pityriasis rosea must be differentiated from dermatophytosis, secondary syphilis, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, erythema annulare centrifugum, and pityriasis rosea-like drug eruptions.1-3,6

Dermatophytosis presents as an annular lesion with central clearing and a peripheral papulovesicular border. Patients will complain that the lesions are itchy. Skin scrapings for potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation reveal fungus under light microscope. (Lab tests do not aid in the diagnosis of pityriasis rosea.)

Secondary syphilis should be suspected in patients with a history of genital ulcers. Patients will have generalized lymphadenopathy and a dusky erythematous papulosquamous rash that involves the palms, soles, and mucosa. A venereal disease research laboratory test will be positive.

Psoriasis involves scaly plaques, typically on the knees, elbows, and scalp. The scales are silvery white and leave minute bleeding points on gentle scraping (Auspitz’s sign). Unlike pityriasis rosea, nail changes are often seen in psoriasis. These changes include pitting on the nail plate, onycholysis, oil drop sign, and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica may mimic pityriasis rosea in distribution, but there are no collarette scales. Also, pityriasis lichenoides chronica does not self-resolve; it requires treatment.

Erythema annulare centrifugum is usually a single large erythematous plaque that slowly expands. There is often a history of a tick bite, and no Christmas tree distribution.

Provide symptomatic Tx

Symptomatic treatment of pityriasis rosea is generally adequate, and includes topical emollients, such as white petrolatum or mid-potency steroid creams and antihistamines for pruritus6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Erythromycin. In one study, erythromycin 250 mg QID for 2 weeks hastened the resolution of pityriasis rosea6 (SOR: B). It was suggested that the anti-inflammatory properties and immune modulation of the drug, rather than its antibiotic effect, may have aided the clinical resolution. However, such efficacy was not substantiated in subsequent trials with erythromycin or another macrolide, azithromycin.7-10

High-dose acyclovir. Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day has been shown to reduce disease severity and duration in some patients with pityriasis rosea.11 However, it is not recommended as first-line therapy2 (SOR: C).

Systemic steroids should be avoided in pityriasis rosea, as they may worsen the disease.6

Is the patient of school age? If so, the evidence suggests that he or she should not be kept out of school.6

My patient

I treated this patient with a topical mid-potency steroid (betamethasone dipropionate) twice daily on the affected areas and an oral antihistamine once daily for 10 days. The patient’s symptoms and skin lesions resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Vijay Zawar, MD, DNB, DVD, FAAD, Skin Diseases Center, 21 Shreeram Sankul, Opp. Hotel Panchavati, Vakilwadi Nashik-422001, Maharashtra, India; vijayzawar@yahoo.com

1. Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303-318.

2. Chuh A, Lee A, Zawar V, et al. Pityriasis rosea—an update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:311-315.

3. González LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757-764.

4. Zawar V, Jerajani H, Pol R. Current trends in pityriasis rosea. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2010;5:325-333.

5. Sharma L, Shrivastava K. Clinico-epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:647-649.

6. Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005068.-

7. Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, et al. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:241-244.

8. Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:35-38.

9. Bukhari IA. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:625.-

10. Amer A, Fischer H. Azithromycin does not cure pityriasis rosea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1702-1705.

11. Drago F, Vecchio F, Rebora A. Use of high-dose acyclovir in pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:82-85.

1. Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303-318.

2. Chuh A, Lee A, Zawar V, et al. Pityriasis rosea—an update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:311-315.

3. González LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757-764.

4. Zawar V, Jerajani H, Pol R. Current trends in pityriasis rosea. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2010;5:325-333.

5. Sharma L, Shrivastava K. Clinico-epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:647-649.

6. Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005068.-

7. Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, et al. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:241-244.

8. Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:35-38.

9. Bukhari IA. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:625.-

10. Amer A, Fischer H. Azithromycin does not cure pityriasis rosea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1702-1705.

11. Drago F, Vecchio F, Rebora A. Use of high-dose acyclovir in pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:82-85.