User login

Bilateral facial swelling

The patient was given a diagnosis of sialadenosis (also known as sialosis), a noninflammatory, non-neoplastic enlargement of the parotid glands. It can often manifest as fatty degeneration of the parotid glands, which may be associated with underlying conditions such as hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.1-3

Ultrasonography and a subsequent computed tomography with contrast demonstrated fatty hypertrophy of the parotid glands without any concerning parotid mass or enlarged cervical lymph nodes. No abnormalities of the ductal system (eg, stricture or obstruction with stone) were noted, so sialography and sialendoscopy were not indicated.

Evaluation for inflammatory, autoimmune, and granulomatous diseases was negative, including negative anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and negative HIV screen. However, our patient had an elevated serum triglyceride level of 589 mg/dL (reference range, < 150 mg/dL), while serum total cholesterol was within the reference range (< 200 mg/dL). (Interestingly, his triglycerides were normal a year earlier.) The patient’s A1c level was normal.

The differential diagnosis for this patient included Sjögren syndrome, abscess, viral infection (eg, mumps, HIV sialopathy), Kimura disease, sarcoidosis, masseter hypertrophy, and tumors of the parotid gland (eg, Warthin tumor and pleomorphic adenoma). Drug-induced sialadenitis was another possibility, as several drugs may be associated with salivary gland enlargement.4 However, no association was found for our patient.

Primary management is focused on treating the underlying disorder. The application of heat, massage, and sialagogues (eg, pilocarpine 5 mg orally tid) can be used to stimulate salivation, which may help reduce the swelling. Bilateral parotid gland swelling in patients with increased triglyceride levels often resolves after treatment of hypertriglyceridemia.3,5 Less common modalities include botulinum neurotoxin injection, tympanic neurectomy, and parotidectomy.6

The treatment plan for this patient included aggressive dietary modification and increasing his current dosage of atorvastatin from 20 mg to 80 mg at bedtime. Increasing the dosage of statin was preferred over adding another agent (such as fibrates) to decrease the risk of myopathy. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy may be considered if the swelling does not resolve after correction of lipid abnormalities, which can take between 6 months and 3 years.3

Photo courtesy of Faryal Tahir, MD. Text courtesy of Faryal Tahir, MD, Assistant Professor, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Garcia DS, Bussoloti Filho I. Fat deposition of parotid glands. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:173-176

2. Hida A, Akahoshi M, Takagi Y, et al. Lipid infiltration in the parotid glands: a clinical manifestation of metabolic syndrome. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:110-115. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291315

3. Sheikh JS, Sharma M, Kunath A, et al. Reversible parotid enlargement and pseudo-Sjögren's syndrome secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1288-1291

4. Vinayak V, Annigeri RG, Patel HA, et al. Adverse effects of drugs on saliva and salivary glands. J Orofac Sci. 2013;5:15-20. doi: 10.4103/0975-8844.113684

5. Kaltreider HB, Talal N. Bilateral parotid gland enlargement and hyperlipoproteinemia. JAMA. 1969;210:2067-2070. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160370051010

6. Davis AB, Hoffman HT. Management options for sialadenosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:605-611. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2021.02.005

The patient was given a diagnosis of sialadenosis (also known as sialosis), a noninflammatory, non-neoplastic enlargement of the parotid glands. It can often manifest as fatty degeneration of the parotid glands, which may be associated with underlying conditions such as hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.1-3

Ultrasonography and a subsequent computed tomography with contrast demonstrated fatty hypertrophy of the parotid glands without any concerning parotid mass or enlarged cervical lymph nodes. No abnormalities of the ductal system (eg, stricture or obstruction with stone) were noted, so sialography and sialendoscopy were not indicated.

Evaluation for inflammatory, autoimmune, and granulomatous diseases was negative, including negative anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and negative HIV screen. However, our patient had an elevated serum triglyceride level of 589 mg/dL (reference range, < 150 mg/dL), while serum total cholesterol was within the reference range (< 200 mg/dL). (Interestingly, his triglycerides were normal a year earlier.) The patient’s A1c level was normal.

The differential diagnosis for this patient included Sjögren syndrome, abscess, viral infection (eg, mumps, HIV sialopathy), Kimura disease, sarcoidosis, masseter hypertrophy, and tumors of the parotid gland (eg, Warthin tumor and pleomorphic adenoma). Drug-induced sialadenitis was another possibility, as several drugs may be associated with salivary gland enlargement.4 However, no association was found for our patient.

Primary management is focused on treating the underlying disorder. The application of heat, massage, and sialagogues (eg, pilocarpine 5 mg orally tid) can be used to stimulate salivation, which may help reduce the swelling. Bilateral parotid gland swelling in patients with increased triglyceride levels often resolves after treatment of hypertriglyceridemia.3,5 Less common modalities include botulinum neurotoxin injection, tympanic neurectomy, and parotidectomy.6

The treatment plan for this patient included aggressive dietary modification and increasing his current dosage of atorvastatin from 20 mg to 80 mg at bedtime. Increasing the dosage of statin was preferred over adding another agent (such as fibrates) to decrease the risk of myopathy. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy may be considered if the swelling does not resolve after correction of lipid abnormalities, which can take between 6 months and 3 years.3

Photo courtesy of Faryal Tahir, MD. Text courtesy of Faryal Tahir, MD, Assistant Professor, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The patient was given a diagnosis of sialadenosis (also known as sialosis), a noninflammatory, non-neoplastic enlargement of the parotid glands. It can often manifest as fatty degeneration of the parotid glands, which may be associated with underlying conditions such as hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.1-3

Ultrasonography and a subsequent computed tomography with contrast demonstrated fatty hypertrophy of the parotid glands without any concerning parotid mass or enlarged cervical lymph nodes. No abnormalities of the ductal system (eg, stricture or obstruction with stone) were noted, so sialography and sialendoscopy were not indicated.

Evaluation for inflammatory, autoimmune, and granulomatous diseases was negative, including negative anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and negative HIV screen. However, our patient had an elevated serum triglyceride level of 589 mg/dL (reference range, < 150 mg/dL), while serum total cholesterol was within the reference range (< 200 mg/dL). (Interestingly, his triglycerides were normal a year earlier.) The patient’s A1c level was normal.

The differential diagnosis for this patient included Sjögren syndrome, abscess, viral infection (eg, mumps, HIV sialopathy), Kimura disease, sarcoidosis, masseter hypertrophy, and tumors of the parotid gland (eg, Warthin tumor and pleomorphic adenoma). Drug-induced sialadenitis was another possibility, as several drugs may be associated with salivary gland enlargement.4 However, no association was found for our patient.

Primary management is focused on treating the underlying disorder. The application of heat, massage, and sialagogues (eg, pilocarpine 5 mg orally tid) can be used to stimulate salivation, which may help reduce the swelling. Bilateral parotid gland swelling in patients with increased triglyceride levels often resolves after treatment of hypertriglyceridemia.3,5 Less common modalities include botulinum neurotoxin injection, tympanic neurectomy, and parotidectomy.6

The treatment plan for this patient included aggressive dietary modification and increasing his current dosage of atorvastatin from 20 mg to 80 mg at bedtime. Increasing the dosage of statin was preferred over adding another agent (such as fibrates) to decrease the risk of myopathy. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy may be considered if the swelling does not resolve after correction of lipid abnormalities, which can take between 6 months and 3 years.3

Photo courtesy of Faryal Tahir, MD. Text courtesy of Faryal Tahir, MD, Assistant Professor, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Garcia DS, Bussoloti Filho I. Fat deposition of parotid glands. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:173-176

2. Hida A, Akahoshi M, Takagi Y, et al. Lipid infiltration in the parotid glands: a clinical manifestation of metabolic syndrome. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:110-115. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291315

3. Sheikh JS, Sharma M, Kunath A, et al. Reversible parotid enlargement and pseudo-Sjögren's syndrome secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1288-1291

4. Vinayak V, Annigeri RG, Patel HA, et al. Adverse effects of drugs on saliva and salivary glands. J Orofac Sci. 2013;5:15-20. doi: 10.4103/0975-8844.113684

5. Kaltreider HB, Talal N. Bilateral parotid gland enlargement and hyperlipoproteinemia. JAMA. 1969;210:2067-2070. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160370051010

6. Davis AB, Hoffman HT. Management options for sialadenosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:605-611. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2021.02.005

1. Garcia DS, Bussoloti Filho I. Fat deposition of parotid glands. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:173-176

2. Hida A, Akahoshi M, Takagi Y, et al. Lipid infiltration in the parotid glands: a clinical manifestation of metabolic syndrome. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:110-115. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291315

3. Sheikh JS, Sharma M, Kunath A, et al. Reversible parotid enlargement and pseudo-Sjögren's syndrome secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1288-1291

4. Vinayak V, Annigeri RG, Patel HA, et al. Adverse effects of drugs on saliva and salivary glands. J Orofac Sci. 2013;5:15-20. doi: 10.4103/0975-8844.113684

5. Kaltreider HB, Talal N. Bilateral parotid gland enlargement and hyperlipoproteinemia. JAMA. 1969;210:2067-2070. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160370051010

6. Davis AB, Hoffman HT. Management options for sialadenosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:605-611. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2021.02.005

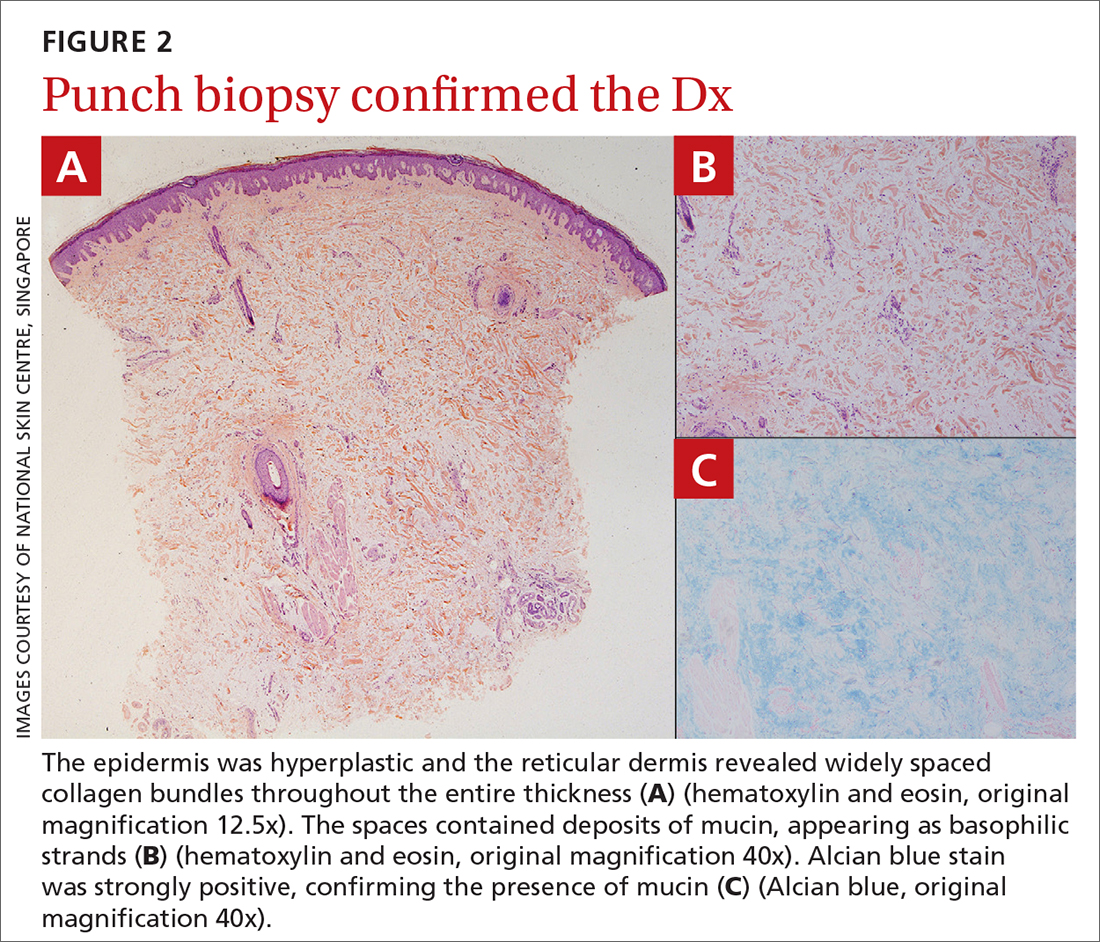

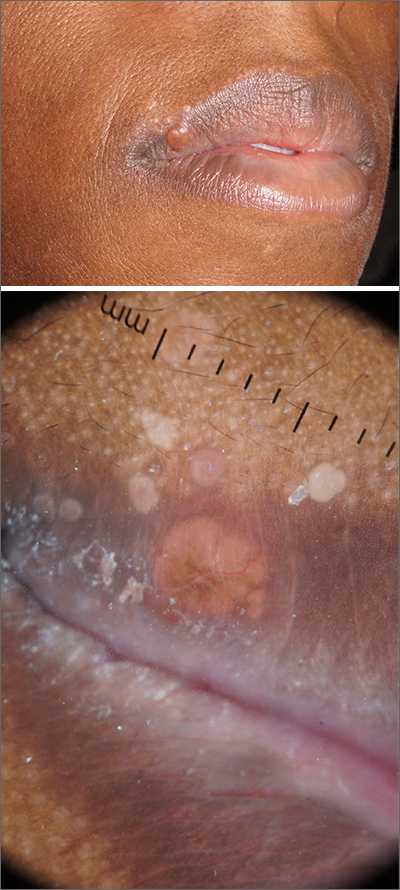

Multiple basal cell carcinomas

These skin findings were the latest manifestation of a condition that the patient had been diagnosed with at age 32: basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), also called Gorlin syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by multiple biopsy-proven BCCs, palmar pitting, frontal bossing, scoliosis, and gum cysts. This patient had had gum cysts since she was 8 years old; her sister and mother had similar gum cysts and her mother had at least 1 BCC. BCNS is caused by an inheritable defect in the Patched 1 (PTCH1) gene, leading to various findings—including numerous BCCs at a young age.1

The Oncology team started the patient on the oral small-molecule chemotherapy agent vismodegib, 150 mg/d. The patient was also referred to Medical Genetics and Wound Care. Although her diagnosis had been made clinically years earlier, genetic testing was performed and confirmed a defect in the PTCH1 gene. This helped with surveillance plans. A computed tomography scan of the head revealed a nasal dermoid cyst of the ethmoid sinus that the Ear, Nose, & Throat and Neurology teams felt safe to observe.

After 3 months of therapy with vismodegib, the patient had significant improvement of facial lesions and significant re-epithelialization of the crown.

Patients on vismodegib often deal with adverse effects, but adjusted dosing regimens have proved to improve tolerability. This patient had substantial adverse effects including fatigue, hair loss, loss of taste, and weight loss (26 lbs). Because of these adverse effects, her regimen was adjusted to 1 month of every other day active treatment and 2 months off treatment, cycled continuously. With this regimen, her weight returned to normal and her sense of taste returned for most days in the treatment cycle.

She has been tolerating this regimen for 3 years with continued control of BCCs.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Yang X, Dinehart SM. Intermittent vismodegib therapy in basal cell nevus syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:223-224. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3210

These skin findings were the latest manifestation of a condition that the patient had been diagnosed with at age 32: basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), also called Gorlin syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by multiple biopsy-proven BCCs, palmar pitting, frontal bossing, scoliosis, and gum cysts. This patient had had gum cysts since she was 8 years old; her sister and mother had similar gum cysts and her mother had at least 1 BCC. BCNS is caused by an inheritable defect in the Patched 1 (PTCH1) gene, leading to various findings—including numerous BCCs at a young age.1

The Oncology team started the patient on the oral small-molecule chemotherapy agent vismodegib, 150 mg/d. The patient was also referred to Medical Genetics and Wound Care. Although her diagnosis had been made clinically years earlier, genetic testing was performed and confirmed a defect in the PTCH1 gene. This helped with surveillance plans. A computed tomography scan of the head revealed a nasal dermoid cyst of the ethmoid sinus that the Ear, Nose, & Throat and Neurology teams felt safe to observe.

After 3 months of therapy with vismodegib, the patient had significant improvement of facial lesions and significant re-epithelialization of the crown.

Patients on vismodegib often deal with adverse effects, but adjusted dosing regimens have proved to improve tolerability. This patient had substantial adverse effects including fatigue, hair loss, loss of taste, and weight loss (26 lbs). Because of these adverse effects, her regimen was adjusted to 1 month of every other day active treatment and 2 months off treatment, cycled continuously. With this regimen, her weight returned to normal and her sense of taste returned for most days in the treatment cycle.

She has been tolerating this regimen for 3 years with continued control of BCCs.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

These skin findings were the latest manifestation of a condition that the patient had been diagnosed with at age 32: basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS), also called Gorlin syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by multiple biopsy-proven BCCs, palmar pitting, frontal bossing, scoliosis, and gum cysts. This patient had had gum cysts since she was 8 years old; her sister and mother had similar gum cysts and her mother had at least 1 BCC. BCNS is caused by an inheritable defect in the Patched 1 (PTCH1) gene, leading to various findings—including numerous BCCs at a young age.1

The Oncology team started the patient on the oral small-molecule chemotherapy agent vismodegib, 150 mg/d. The patient was also referred to Medical Genetics and Wound Care. Although her diagnosis had been made clinically years earlier, genetic testing was performed and confirmed a defect in the PTCH1 gene. This helped with surveillance plans. A computed tomography scan of the head revealed a nasal dermoid cyst of the ethmoid sinus that the Ear, Nose, & Throat and Neurology teams felt safe to observe.

After 3 months of therapy with vismodegib, the patient had significant improvement of facial lesions and significant re-epithelialization of the crown.

Patients on vismodegib often deal with adverse effects, but adjusted dosing regimens have proved to improve tolerability. This patient had substantial adverse effects including fatigue, hair loss, loss of taste, and weight loss (26 lbs). Because of these adverse effects, her regimen was adjusted to 1 month of every other day active treatment and 2 months off treatment, cycled continuously. With this regimen, her weight returned to normal and her sense of taste returned for most days in the treatment cycle.

She has been tolerating this regimen for 3 years with continued control of BCCs.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Yang X, Dinehart SM. Intermittent vismodegib therapy in basal cell nevus syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:223-224. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3210

1. Yang X, Dinehart SM. Intermittent vismodegib therapy in basal cell nevus syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:223-224. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3210

Painless nodules on legs

A 34-YEAR-OLD MAN presented with a 6-month history of asymptomatic, progressively enlarging subcutaneous nodules over his bilateral lower legs. He denied any history of injury, and there was no bleeding or discharge. The patient had a history of Graves disease that had been treated with radioiodine therapy 2 years prior, followed by thyroxine replacement (150 mcg/d, 5 d/wk and 125 mcg/d, 2 d/wk). At the time of presentation, his thyroid function tests indicated subclinical hypothyroidism: free T4, 21.2 pmol/L (normal range, 11.8-24.6 pmol/L) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 14.07 mIU/L (normal range, 0.27-4.2 mIU/L).

Examination revealed nontender, soft brown nodules over the bilateral shins, with minimal overlying lichenification (FIGURE 1). There was no peau d’orange (orange peel) appearance to suggest significant edema. A punch biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pretibial myxedema

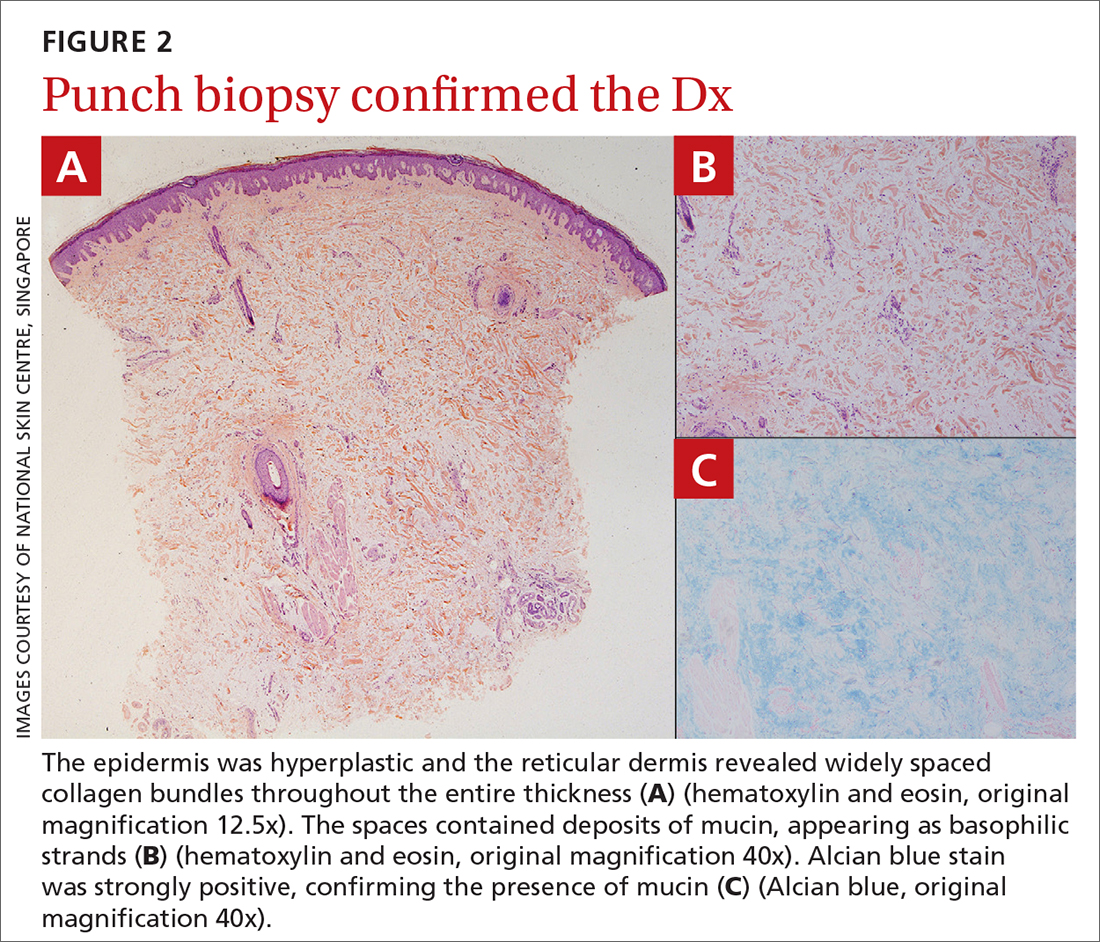

The patient’s history, paired with the results of the punch biopsy, were consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema, part of the triad of Graves disease along with thyroid ophthalmopathy and acropachy (soft-tissue swelling of the hands and clubbing of the fingers). Histopathologic findings revealed wide separation of collagen bundles throughout the entire reticular dermis without fibroplasia (FIGURE 2A). The spaces contained basophilic strands (FIGURE 2B), and the strands stained strongly positive on Alcian blue (FIGURE 2C), confirming the presence of dermal mucin. Widely separated collagen fibers and deposited mucin are indicative of pretibial myxedema. No granulomas or lymphoid proliferations were seen.

The pathogenesis of pretibial myxedema is widely postulated to be due to the stimulation of dermal fibroblasts by anti–TSH antibodies, causing overproduction of glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronic acid1 and obstructing lymphatic microcirculation, resulting in nonpitting edema.2

There are 5 distinct clinical variants of pretibial myxedema1,3:

- The diffuse form is the most common. It manifests on the lower leg with hard, nonpitting edema and cutaneous thickening.

- The plaque form manifests on the lower leg as well-demarcated erythematous or pigmented flat-topped lesions.

- The nodular form, which our patient had, typically manifests on the lower leg as well-demarcated erythematous, pigmented, or skin-colored raised, solid lesions. There may be 1 lesion or several.

- The mixed form manifests as 2 or more of the other variants.

- The elephantiasic form is the rarest and the most severe. There are widespread swollen nodules and plaques on the lower legs and/or arms.

A rare, late manifestation

Although pathognomonic for Graves disease, pretibial myxedema is a late manifestation that occurs in less than 5% of these patients.4 The most common site of involvement is the pretibial region, although less common sites include the face, arms, shoulders, abdomen, pinna, and the location of previous scars.4

While pretibial myxedema usually is associated with hyperthyroidism, it can occur after treatment (as was the case here), while the patient is in a euthyroid or hypothyroid state. Radioiodine therapy has been reported to be a trigger for pretibial myxedema in 1 case report, although the pathophysiology is not fully understood.5

Continue to: More serious conditions must be ruled out

More serious conditions must be ruled out

The differential for painless nodules includes cutaneous lymphoma and atypical infections of fungal or mycobacterial etiology.

Cutaneous lymphoma that manifests with leg tumors includes primary cutaneous anaplastic CD30+ large cell lymphoma (PCALCL) and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBL-LT). The former may occur in young patients, whereas the latter tends to manifest in the elderly. Biopsy shows a neoplastic proliferation of atypical lymphocytes within the dermis,6 differing from our case.

Atypical infections may be detected through bacterial, mycobacterial, or fungal cultures, and may be accompanied by elevated inflammatory markers or other systemic symptoms of the infection, setting it apart from pretibial myxedema.

Treatment is simple and noninvasive

Pretibial myxedema is usually asymptomatic, with minimal morbidity. The nodular variant may resolve spontaneously; thus, therapeutic management often is reserved for severe cases or for those with cosmetic concerns. Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids with an occlusive dressing for 1 to 2 weeks (or until resolution) or an intralesional triamcinolone injection (5-10 mg/mL, single or monthly until resolution), compression stockings, and pneumatic compression.2

This patient was treated with a single intralesional injection of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL. The nodules resolved within a month.

1. Thammarucha S, Sudtikoonaseth P. Nodular pretibial myxedema with Graves’ disease: a case report. Thai J Dermatol. 2021;37:30-36.

2. Singla M, Gupta A. Nodular thyroid dermopathy: not a hallmark of Graves’ disease. Am J Med. 2019;132:e521-e522. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.11.004

3. Lan C, Wang Y, Zeng X, et al. Morphological diversity of pretibial myxedema and its mechanism of evolving process and outcome: a retrospective study of 216 cases. J Thyroid Res. 2016:2016:265217

4. doi: 10.1155/2016/2652174 4. Patil MM, Kamalanathan S, Sahoo J, et al. Pretibial myxedema. QJM. 2015;108:985. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv136

5. Harvey RD, Metcalfe RA, Morteo C, et al. Acute pre-tibial myxoedema following radioiodine therapy for thyrotoxic Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;42:657-660. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02695.x

6. Schukow C, Ahmed A. Dermatopathology, cutaneous lymphomas. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 16, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589703/

A 34-YEAR-OLD MAN presented with a 6-month history of asymptomatic, progressively enlarging subcutaneous nodules over his bilateral lower legs. He denied any history of injury, and there was no bleeding or discharge. The patient had a history of Graves disease that had been treated with radioiodine therapy 2 years prior, followed by thyroxine replacement (150 mcg/d, 5 d/wk and 125 mcg/d, 2 d/wk). At the time of presentation, his thyroid function tests indicated subclinical hypothyroidism: free T4, 21.2 pmol/L (normal range, 11.8-24.6 pmol/L) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 14.07 mIU/L (normal range, 0.27-4.2 mIU/L).

Examination revealed nontender, soft brown nodules over the bilateral shins, with minimal overlying lichenification (FIGURE 1). There was no peau d’orange (orange peel) appearance to suggest significant edema. A punch biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pretibial myxedema

The patient’s history, paired with the results of the punch biopsy, were consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema, part of the triad of Graves disease along with thyroid ophthalmopathy and acropachy (soft-tissue swelling of the hands and clubbing of the fingers). Histopathologic findings revealed wide separation of collagen bundles throughout the entire reticular dermis without fibroplasia (FIGURE 2A). The spaces contained basophilic strands (FIGURE 2B), and the strands stained strongly positive on Alcian blue (FIGURE 2C), confirming the presence of dermal mucin. Widely separated collagen fibers and deposited mucin are indicative of pretibial myxedema. No granulomas or lymphoid proliferations were seen.

The pathogenesis of pretibial myxedema is widely postulated to be due to the stimulation of dermal fibroblasts by anti–TSH antibodies, causing overproduction of glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronic acid1 and obstructing lymphatic microcirculation, resulting in nonpitting edema.2

There are 5 distinct clinical variants of pretibial myxedema1,3:

- The diffuse form is the most common. It manifests on the lower leg with hard, nonpitting edema and cutaneous thickening.

- The plaque form manifests on the lower leg as well-demarcated erythematous or pigmented flat-topped lesions.

- The nodular form, which our patient had, typically manifests on the lower leg as well-demarcated erythematous, pigmented, or skin-colored raised, solid lesions. There may be 1 lesion or several.

- The mixed form manifests as 2 or more of the other variants.

- The elephantiasic form is the rarest and the most severe. There are widespread swollen nodules and plaques on the lower legs and/or arms.

A rare, late manifestation

Although pathognomonic for Graves disease, pretibial myxedema is a late manifestation that occurs in less than 5% of these patients.4 The most common site of involvement is the pretibial region, although less common sites include the face, arms, shoulders, abdomen, pinna, and the location of previous scars.4

While pretibial myxedema usually is associated with hyperthyroidism, it can occur after treatment (as was the case here), while the patient is in a euthyroid or hypothyroid state. Radioiodine therapy has been reported to be a trigger for pretibial myxedema in 1 case report, although the pathophysiology is not fully understood.5

Continue to: More serious conditions must be ruled out

More serious conditions must be ruled out

The differential for painless nodules includes cutaneous lymphoma and atypical infections of fungal or mycobacterial etiology.

Cutaneous lymphoma that manifests with leg tumors includes primary cutaneous anaplastic CD30+ large cell lymphoma (PCALCL) and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBL-LT). The former may occur in young patients, whereas the latter tends to manifest in the elderly. Biopsy shows a neoplastic proliferation of atypical lymphocytes within the dermis,6 differing from our case.

Atypical infections may be detected through bacterial, mycobacterial, or fungal cultures, and may be accompanied by elevated inflammatory markers or other systemic symptoms of the infection, setting it apart from pretibial myxedema.

Treatment is simple and noninvasive

Pretibial myxedema is usually asymptomatic, with minimal morbidity. The nodular variant may resolve spontaneously; thus, therapeutic management often is reserved for severe cases or for those with cosmetic concerns. Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids with an occlusive dressing for 1 to 2 weeks (or until resolution) or an intralesional triamcinolone injection (5-10 mg/mL, single or monthly until resolution), compression stockings, and pneumatic compression.2

This patient was treated with a single intralesional injection of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL. The nodules resolved within a month.

A 34-YEAR-OLD MAN presented with a 6-month history of asymptomatic, progressively enlarging subcutaneous nodules over his bilateral lower legs. He denied any history of injury, and there was no bleeding or discharge. The patient had a history of Graves disease that had been treated with radioiodine therapy 2 years prior, followed by thyroxine replacement (150 mcg/d, 5 d/wk and 125 mcg/d, 2 d/wk). At the time of presentation, his thyroid function tests indicated subclinical hypothyroidism: free T4, 21.2 pmol/L (normal range, 11.8-24.6 pmol/L) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 14.07 mIU/L (normal range, 0.27-4.2 mIU/L).

Examination revealed nontender, soft brown nodules over the bilateral shins, with minimal overlying lichenification (FIGURE 1). There was no peau d’orange (orange peel) appearance to suggest significant edema. A punch biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pretibial myxedema

The patient’s history, paired with the results of the punch biopsy, were consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema, part of the triad of Graves disease along with thyroid ophthalmopathy and acropachy (soft-tissue swelling of the hands and clubbing of the fingers). Histopathologic findings revealed wide separation of collagen bundles throughout the entire reticular dermis without fibroplasia (FIGURE 2A). The spaces contained basophilic strands (FIGURE 2B), and the strands stained strongly positive on Alcian blue (FIGURE 2C), confirming the presence of dermal mucin. Widely separated collagen fibers and deposited mucin are indicative of pretibial myxedema. No granulomas or lymphoid proliferations were seen.

The pathogenesis of pretibial myxedema is widely postulated to be due to the stimulation of dermal fibroblasts by anti–TSH antibodies, causing overproduction of glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronic acid1 and obstructing lymphatic microcirculation, resulting in nonpitting edema.2

There are 5 distinct clinical variants of pretibial myxedema1,3:

- The diffuse form is the most common. It manifests on the lower leg with hard, nonpitting edema and cutaneous thickening.

- The plaque form manifests on the lower leg as well-demarcated erythematous or pigmented flat-topped lesions.

- The nodular form, which our patient had, typically manifests on the lower leg as well-demarcated erythematous, pigmented, or skin-colored raised, solid lesions. There may be 1 lesion or several.

- The mixed form manifests as 2 or more of the other variants.

- The elephantiasic form is the rarest and the most severe. There are widespread swollen nodules and plaques on the lower legs and/or arms.

A rare, late manifestation

Although pathognomonic for Graves disease, pretibial myxedema is a late manifestation that occurs in less than 5% of these patients.4 The most common site of involvement is the pretibial region, although less common sites include the face, arms, shoulders, abdomen, pinna, and the location of previous scars.4

While pretibial myxedema usually is associated with hyperthyroidism, it can occur after treatment (as was the case here), while the patient is in a euthyroid or hypothyroid state. Radioiodine therapy has been reported to be a trigger for pretibial myxedema in 1 case report, although the pathophysiology is not fully understood.5

Continue to: More serious conditions must be ruled out

More serious conditions must be ruled out

The differential for painless nodules includes cutaneous lymphoma and atypical infections of fungal or mycobacterial etiology.

Cutaneous lymphoma that manifests with leg tumors includes primary cutaneous anaplastic CD30+ large cell lymphoma (PCALCL) and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBL-LT). The former may occur in young patients, whereas the latter tends to manifest in the elderly. Biopsy shows a neoplastic proliferation of atypical lymphocytes within the dermis,6 differing from our case.

Atypical infections may be detected through bacterial, mycobacterial, or fungal cultures, and may be accompanied by elevated inflammatory markers or other systemic symptoms of the infection, setting it apart from pretibial myxedema.

Treatment is simple and noninvasive

Pretibial myxedema is usually asymptomatic, with minimal morbidity. The nodular variant may resolve spontaneously; thus, therapeutic management often is reserved for severe cases or for those with cosmetic concerns. Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids with an occlusive dressing for 1 to 2 weeks (or until resolution) or an intralesional triamcinolone injection (5-10 mg/mL, single or monthly until resolution), compression stockings, and pneumatic compression.2

This patient was treated with a single intralesional injection of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL. The nodules resolved within a month.

1. Thammarucha S, Sudtikoonaseth P. Nodular pretibial myxedema with Graves’ disease: a case report. Thai J Dermatol. 2021;37:30-36.

2. Singla M, Gupta A. Nodular thyroid dermopathy: not a hallmark of Graves’ disease. Am J Med. 2019;132:e521-e522. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.11.004

3. Lan C, Wang Y, Zeng X, et al. Morphological diversity of pretibial myxedema and its mechanism of evolving process and outcome: a retrospective study of 216 cases. J Thyroid Res. 2016:2016:265217

4. doi: 10.1155/2016/2652174 4. Patil MM, Kamalanathan S, Sahoo J, et al. Pretibial myxedema. QJM. 2015;108:985. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv136

5. Harvey RD, Metcalfe RA, Morteo C, et al. Acute pre-tibial myxoedema following radioiodine therapy for thyrotoxic Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;42:657-660. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02695.x

6. Schukow C, Ahmed A. Dermatopathology, cutaneous lymphomas. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 16, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589703/

1. Thammarucha S, Sudtikoonaseth P. Nodular pretibial myxedema with Graves’ disease: a case report. Thai J Dermatol. 2021;37:30-36.

2. Singla M, Gupta A. Nodular thyroid dermopathy: not a hallmark of Graves’ disease. Am J Med. 2019;132:e521-e522. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.11.004

3. Lan C, Wang Y, Zeng X, et al. Morphological diversity of pretibial myxedema and its mechanism of evolving process and outcome: a retrospective study of 216 cases. J Thyroid Res. 2016:2016:265217

4. doi: 10.1155/2016/2652174 4. Patil MM, Kamalanathan S, Sahoo J, et al. Pretibial myxedema. QJM. 2015;108:985. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv136

5. Harvey RD, Metcalfe RA, Morteo C, et al. Acute pre-tibial myxoedema following radioiodine therapy for thyrotoxic Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;42:657-660. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02695.x

6. Schukow C, Ahmed A. Dermatopathology, cutaneous lymphomas. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 16, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589703/

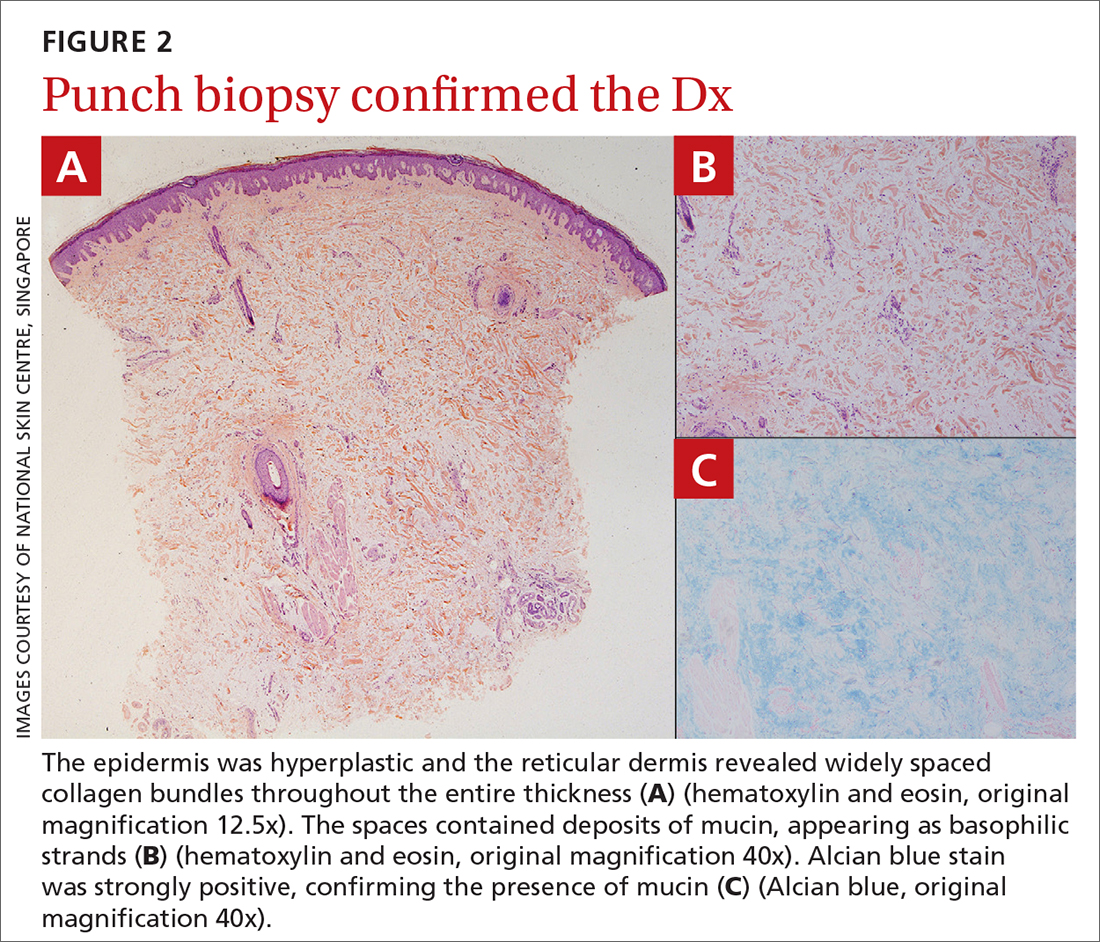

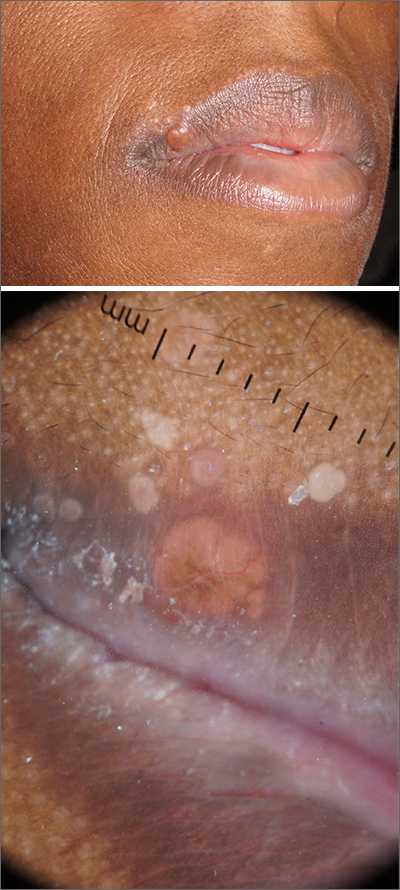

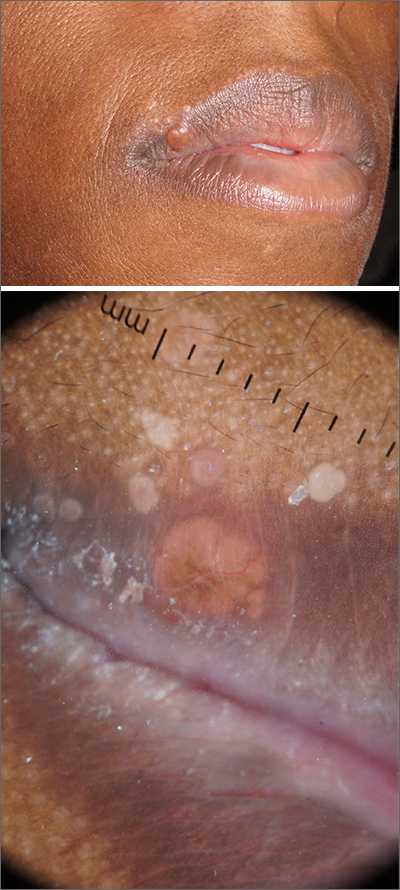

Papules on lip

Pathology showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with cutaneous sarcoidosis. Based on these biopsy findings, a chest x-ray was ordered, and it confirmed a pulmonary sarcoid. A multidisciplinary work-up (including cardiac evaluation, continued rheumatologic care, and evaluation by Hematology) addressed this new finding.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of granulomas that can arise in any organ, but frequently involve the skin and lungs. Patients with cutaneous disease develop smooth skin lesions, including flesh-colored to pink or brown papules on the face. Genetic and environmental factors are both thought to contribute to the disease.

Race is a significant factor in the development of disease. Hispanic and Asian patients are significantly less likely to develop the disease compared to White or Black patients. In the Black Women’s Health Study, incidence in Black women was 71 per 100,000.1 Women are more likely to be affected than men.1

Many patients with sarcoidosis have a mild course, but for others the disease may progress on the skin or include pulmonary, renal, neurologic, or cardiac disease. Sometimes sarcoidosis is fatal. Recurrence can occur at any point later in life. Race influences disease severity as well as incidence, with hospitalization being 9 times as likely in Black patients compared with White patients.2 One recent study puts sarcoidosis mortality rates for Black women at 10 per million compared with 3 per million in Black men, and 1 per million in White women or men.3

Patients with disease limited to the skin may be treated with topical steroids such as clobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment or intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injected into affected lesions every 2 to 4 weeks. With pulmonary or other systemic disease, treatment may include various disease-modifying agents including prednisone, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors. Because of the long-term adverse effects of systemic steroids, these agents are reserved for instances when pulmonary function is significantly impacted.

This patient had a reassuring cardiac and hematology work-up. Her pulmonary function was impacted sufficiently enough that her pulmonologist added a course of prednisone 10 mg daily tapered over 6 weeks. She had been on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily prior to the diagnosis of sarcoidosis for presumed mixed connective tissue disease and was continued on it for sarcoidosis after completing the prednisone taper. With these treatments, her facial lesions cleared and her breathing symptoms and fatigue improved. She remains under surveillance with a multidisciplinary team.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Cozier Y, Berman J, Palmer J, et al. Sarcoidosis in black women in the United States: data from the Black Women's Health Study. Chest. 2011;139:144-150. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0413

2. Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Kamugisha L, et al. Hospitalization for patients with sarcoidosis: 1979-2000. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:124-129.

3. Mirsaeidi M, Machado R, Schraufnagel D, et al. Racial difference in sarcoidosis mortality in the United States. Chest. 2015; 147: 438-449. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1120

Pathology showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with cutaneous sarcoidosis. Based on these biopsy findings, a chest x-ray was ordered, and it confirmed a pulmonary sarcoid. A multidisciplinary work-up (including cardiac evaluation, continued rheumatologic care, and evaluation by Hematology) addressed this new finding.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of granulomas that can arise in any organ, but frequently involve the skin and lungs. Patients with cutaneous disease develop smooth skin lesions, including flesh-colored to pink or brown papules on the face. Genetic and environmental factors are both thought to contribute to the disease.

Race is a significant factor in the development of disease. Hispanic and Asian patients are significantly less likely to develop the disease compared to White or Black patients. In the Black Women’s Health Study, incidence in Black women was 71 per 100,000.1 Women are more likely to be affected than men.1

Many patients with sarcoidosis have a mild course, but for others the disease may progress on the skin or include pulmonary, renal, neurologic, or cardiac disease. Sometimes sarcoidosis is fatal. Recurrence can occur at any point later in life. Race influences disease severity as well as incidence, with hospitalization being 9 times as likely in Black patients compared with White patients.2 One recent study puts sarcoidosis mortality rates for Black women at 10 per million compared with 3 per million in Black men, and 1 per million in White women or men.3

Patients with disease limited to the skin may be treated with topical steroids such as clobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment or intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injected into affected lesions every 2 to 4 weeks. With pulmonary or other systemic disease, treatment may include various disease-modifying agents including prednisone, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors. Because of the long-term adverse effects of systemic steroids, these agents are reserved for instances when pulmonary function is significantly impacted.

This patient had a reassuring cardiac and hematology work-up. Her pulmonary function was impacted sufficiently enough that her pulmonologist added a course of prednisone 10 mg daily tapered over 6 weeks. She had been on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily prior to the diagnosis of sarcoidosis for presumed mixed connective tissue disease and was continued on it for sarcoidosis after completing the prednisone taper. With these treatments, her facial lesions cleared and her breathing symptoms and fatigue improved. She remains under surveillance with a multidisciplinary team.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Pathology showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with cutaneous sarcoidosis. Based on these biopsy findings, a chest x-ray was ordered, and it confirmed a pulmonary sarcoid. A multidisciplinary work-up (including cardiac evaluation, continued rheumatologic care, and evaluation by Hematology) addressed this new finding.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of granulomas that can arise in any organ, but frequently involve the skin and lungs. Patients with cutaneous disease develop smooth skin lesions, including flesh-colored to pink or brown papules on the face. Genetic and environmental factors are both thought to contribute to the disease.

Race is a significant factor in the development of disease. Hispanic and Asian patients are significantly less likely to develop the disease compared to White or Black patients. In the Black Women’s Health Study, incidence in Black women was 71 per 100,000.1 Women are more likely to be affected than men.1

Many patients with sarcoidosis have a mild course, but for others the disease may progress on the skin or include pulmonary, renal, neurologic, or cardiac disease. Sometimes sarcoidosis is fatal. Recurrence can occur at any point later in life. Race influences disease severity as well as incidence, with hospitalization being 9 times as likely in Black patients compared with White patients.2 One recent study puts sarcoidosis mortality rates for Black women at 10 per million compared with 3 per million in Black men, and 1 per million in White women or men.3

Patients with disease limited to the skin may be treated with topical steroids such as clobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment or intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injected into affected lesions every 2 to 4 weeks. With pulmonary or other systemic disease, treatment may include various disease-modifying agents including prednisone, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors. Because of the long-term adverse effects of systemic steroids, these agents are reserved for instances when pulmonary function is significantly impacted.

This patient had a reassuring cardiac and hematology work-up. Her pulmonary function was impacted sufficiently enough that her pulmonologist added a course of prednisone 10 mg daily tapered over 6 weeks. She had been on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily prior to the diagnosis of sarcoidosis for presumed mixed connective tissue disease and was continued on it for sarcoidosis after completing the prednisone taper. With these treatments, her facial lesions cleared and her breathing symptoms and fatigue improved. She remains under surveillance with a multidisciplinary team.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Cozier Y, Berman J, Palmer J, et al. Sarcoidosis in black women in the United States: data from the Black Women's Health Study. Chest. 2011;139:144-150. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0413

2. Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Kamugisha L, et al. Hospitalization for patients with sarcoidosis: 1979-2000. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:124-129.

3. Mirsaeidi M, Machado R, Schraufnagel D, et al. Racial difference in sarcoidosis mortality in the United States. Chest. 2015; 147: 438-449. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1120

1. Cozier Y, Berman J, Palmer J, et al. Sarcoidosis in black women in the United States: data from the Black Women's Health Study. Chest. 2011;139:144-150. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0413

2. Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Kamugisha L, et al. Hospitalization for patients with sarcoidosis: 1979-2000. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:124-129.

3. Mirsaeidi M, Machado R, Schraufnagel D, et al. Racial difference in sarcoidosis mortality in the United States. Chest. 2015; 147: 438-449. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1120

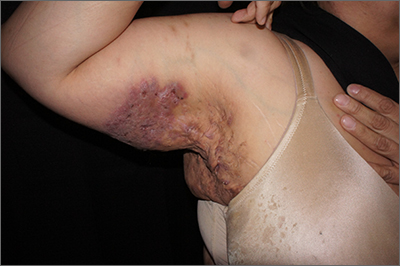

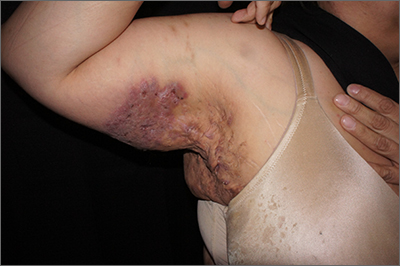

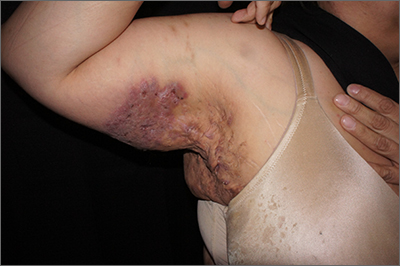

Painful axillary plaque

The persistent scars with recurrent abscesses and sinuses are indicative of advanced hidradenitis suppurativa. This painful and debilitating disease is characterized by the recurrent formation and inflammation of papules, cysts, sinuses, and scars in the axillae, inguinal folds, gluteal cleft, and inframammary folds. Pain, social isolation, depression, increased risk of substance abuse, and increased suicidality are all associated with hidradenitis suppurativa.

The disease may be graded based on severity, which can guide medical treatment options. The earliest stage appears similar to acne without significant sinus tract or scar formation and may be treated with topical therapies—including clindamycin 1% lotion or gel. When larger cysts associated with sinus tracts occur, systemic options with oral antibiotics (including doxycycline 100 mg bid for 3 months or combination clindamycin 300 mg and rifampin 300 mg, both bid for 3 months) are reasonable options. Intralesional triamcinolone in a concentration of 10 mg/mL injected directly into an inflamed cyst can provide acute relief. Severe disease is characterized by diffuse scars and sinus tracts. The TNF-alpha inhibitors adalimumab and infliximab are excellent options for severe disease that does not respond to antibiotics.

Surgical treatment may include either “deroofing” the sinuses or performing a wide excision of the whole area of involvement. Widely excised areas may be grafted, allowed to granulate, or closed if small enough. Although these options create significant wounds, patients experience good results; there is a 27% recurrence with deroofing and a 13% recurrence with wide excision.1

This patient underwent wide local excision of both axillae and the areas of involvement were allowed to granulate. Secondary intention healing occurred over 12 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Orenstein LAV, Nguyen TV, Damiani G, et al. Medical and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of international treatment guidelines and implementation in general dermatology practice. Dermatology. 2020;236:393-412. doi: 10.1159/000507323

The persistent scars with recurrent abscesses and sinuses are indicative of advanced hidradenitis suppurativa. This painful and debilitating disease is characterized by the recurrent formation and inflammation of papules, cysts, sinuses, and scars in the axillae, inguinal folds, gluteal cleft, and inframammary folds. Pain, social isolation, depression, increased risk of substance abuse, and increased suicidality are all associated with hidradenitis suppurativa.

The disease may be graded based on severity, which can guide medical treatment options. The earliest stage appears similar to acne without significant sinus tract or scar formation and may be treated with topical therapies—including clindamycin 1% lotion or gel. When larger cysts associated with sinus tracts occur, systemic options with oral antibiotics (including doxycycline 100 mg bid for 3 months or combination clindamycin 300 mg and rifampin 300 mg, both bid for 3 months) are reasonable options. Intralesional triamcinolone in a concentration of 10 mg/mL injected directly into an inflamed cyst can provide acute relief. Severe disease is characterized by diffuse scars and sinus tracts. The TNF-alpha inhibitors adalimumab and infliximab are excellent options for severe disease that does not respond to antibiotics.

Surgical treatment may include either “deroofing” the sinuses or performing a wide excision of the whole area of involvement. Widely excised areas may be grafted, allowed to granulate, or closed if small enough. Although these options create significant wounds, patients experience good results; there is a 27% recurrence with deroofing and a 13% recurrence with wide excision.1

This patient underwent wide local excision of both axillae and the areas of involvement were allowed to granulate. Secondary intention healing occurred over 12 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The persistent scars with recurrent abscesses and sinuses are indicative of advanced hidradenitis suppurativa. This painful and debilitating disease is characterized by the recurrent formation and inflammation of papules, cysts, sinuses, and scars in the axillae, inguinal folds, gluteal cleft, and inframammary folds. Pain, social isolation, depression, increased risk of substance abuse, and increased suicidality are all associated with hidradenitis suppurativa.

The disease may be graded based on severity, which can guide medical treatment options. The earliest stage appears similar to acne without significant sinus tract or scar formation and may be treated with topical therapies—including clindamycin 1% lotion or gel. When larger cysts associated with sinus tracts occur, systemic options with oral antibiotics (including doxycycline 100 mg bid for 3 months or combination clindamycin 300 mg and rifampin 300 mg, both bid for 3 months) are reasonable options. Intralesional triamcinolone in a concentration of 10 mg/mL injected directly into an inflamed cyst can provide acute relief. Severe disease is characterized by diffuse scars and sinus tracts. The TNF-alpha inhibitors adalimumab and infliximab are excellent options for severe disease that does not respond to antibiotics.

Surgical treatment may include either “deroofing” the sinuses or performing a wide excision of the whole area of involvement. Widely excised areas may be grafted, allowed to granulate, or closed if small enough. Although these options create significant wounds, patients experience good results; there is a 27% recurrence with deroofing and a 13% recurrence with wide excision.1

This patient underwent wide local excision of both axillae and the areas of involvement were allowed to granulate. Secondary intention healing occurred over 12 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Orenstein LAV, Nguyen TV, Damiani G, et al. Medical and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of international treatment guidelines and implementation in general dermatology practice. Dermatology. 2020;236:393-412. doi: 10.1159/000507323

1. Orenstein LAV, Nguyen TV, Damiani G, et al. Medical and surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of international treatment guidelines and implementation in general dermatology practice. Dermatology. 2020;236:393-412. doi: 10.1159/000507323

Frustrating facial lesions

These tender nodules are classic for cystic acne and are common in women older than 20 years. Instead of outgrowing acne in their teenage years, some people (such as this patient) develop frequent tender cystic acne lesions that often heal with hyperpigmented scars.

Acne is the most prevalent chronic skin condition in the United States, affecting up to 50 million people.1 Approximately 12% of adult women are affected.2 The main contributing factors include increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, microbial follicular colonization with Propionibacterium acnes, and an inflammatory reaction.3

Treatment is available in both topical and oral forms. Topical antibiotics are used predominantly for treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. They are not recommended as monotherapy due to the risk for bacterial resistance; this can be prevented by adding benzoyl peroxide, which exfoliates and acts as an antibacterial agent. Clindamycin 1% solution or gel is the preferred topical antibiotic for treatment of acne.4

Topical retinoids can be used as monotherapy or in combination with antibiotics. They also can be used for maintenance after treatment goals are reached and systemic antibiotics are discontinued. Retinoids generally are applied in the evening because the sun weakens their effect. Patients on retinoids also are more sensitive to the sun and should be counseled to use sunscreen daily. Counseling on pregnancy risks and appropriate use of contraception also should be offered to patients using retinoids. It is advisable to consider the use of combination oral contraceptives, particularly in women who have adult-onset acne or experience flare-ups around the time of their menstrual cycle.3

Azelaic acid has anticomedonal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties and may be effective in treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne and hyperpigmentation. Salicylic acid also has comedolytic properties, although there have been limited studies examining its effectiveness. Both azelaic and salicylic acid are considered safe for use in pregnancy.

Oral antibiotics are recommended in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. Both doxycycline and minocycline are more effective than tetracycline for treating acne, with no clear superiority between the two.4 Macrolides also can be effective in treating acne, although their use should be limited to those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines. Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to 3 to 4 months due to decreasing efficacy over time and to minimize the development of bacterial resistance. If treatment goals are attained, the antibiotics can be replaced with retinoids.

Oral isotretinoin is reserved for treatment of severe nodular acne or moderate acne that is treatment resistant. Patients should be counseled on contraceptive methods, as isotretinoin is highly teratogenic and therefore prescribed through the iPLEDGE program.3,4

Given this patient’s persistent symptoms despite use of topical antibiotics and topical tretinoin, she decided to try oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for 3 months and to start long-term oral contraceptives. If her symptoms continue, she will enroll in the iPLEDGE program and start treatment with oral isotretinoin.

Photo courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD. Text courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

2. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

3. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

4. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

These tender nodules are classic for cystic acne and are common in women older than 20 years. Instead of outgrowing acne in their teenage years, some people (such as this patient) develop frequent tender cystic acne lesions that often heal with hyperpigmented scars.

Acne is the most prevalent chronic skin condition in the United States, affecting up to 50 million people.1 Approximately 12% of adult women are affected.2 The main contributing factors include increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, microbial follicular colonization with Propionibacterium acnes, and an inflammatory reaction.3

Treatment is available in both topical and oral forms. Topical antibiotics are used predominantly for treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. They are not recommended as monotherapy due to the risk for bacterial resistance; this can be prevented by adding benzoyl peroxide, which exfoliates and acts as an antibacterial agent. Clindamycin 1% solution or gel is the preferred topical antibiotic for treatment of acne.4

Topical retinoids can be used as monotherapy or in combination with antibiotics. They also can be used for maintenance after treatment goals are reached and systemic antibiotics are discontinued. Retinoids generally are applied in the evening because the sun weakens their effect. Patients on retinoids also are more sensitive to the sun and should be counseled to use sunscreen daily. Counseling on pregnancy risks and appropriate use of contraception also should be offered to patients using retinoids. It is advisable to consider the use of combination oral contraceptives, particularly in women who have adult-onset acne or experience flare-ups around the time of their menstrual cycle.3

Azelaic acid has anticomedonal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties and may be effective in treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne and hyperpigmentation. Salicylic acid also has comedolytic properties, although there have been limited studies examining its effectiveness. Both azelaic and salicylic acid are considered safe for use in pregnancy.

Oral antibiotics are recommended in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. Both doxycycline and minocycline are more effective than tetracycline for treating acne, with no clear superiority between the two.4 Macrolides also can be effective in treating acne, although their use should be limited to those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines. Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to 3 to 4 months due to decreasing efficacy over time and to minimize the development of bacterial resistance. If treatment goals are attained, the antibiotics can be replaced with retinoids.

Oral isotretinoin is reserved for treatment of severe nodular acne or moderate acne that is treatment resistant. Patients should be counseled on contraceptive methods, as isotretinoin is highly teratogenic and therefore prescribed through the iPLEDGE program.3,4

Given this patient’s persistent symptoms despite use of topical antibiotics and topical tretinoin, she decided to try oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for 3 months and to start long-term oral contraceptives. If her symptoms continue, she will enroll in the iPLEDGE program and start treatment with oral isotretinoin.

Photo courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD. Text courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

These tender nodules are classic for cystic acne and are common in women older than 20 years. Instead of outgrowing acne in their teenage years, some people (such as this patient) develop frequent tender cystic acne lesions that often heal with hyperpigmented scars.

Acne is the most prevalent chronic skin condition in the United States, affecting up to 50 million people.1 Approximately 12% of adult women are affected.2 The main contributing factors include increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, microbial follicular colonization with Propionibacterium acnes, and an inflammatory reaction.3

Treatment is available in both topical and oral forms. Topical antibiotics are used predominantly for treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. They are not recommended as monotherapy due to the risk for bacterial resistance; this can be prevented by adding benzoyl peroxide, which exfoliates and acts as an antibacterial agent. Clindamycin 1% solution or gel is the preferred topical antibiotic for treatment of acne.4

Topical retinoids can be used as monotherapy or in combination with antibiotics. They also can be used for maintenance after treatment goals are reached and systemic antibiotics are discontinued. Retinoids generally are applied in the evening because the sun weakens their effect. Patients on retinoids also are more sensitive to the sun and should be counseled to use sunscreen daily. Counseling on pregnancy risks and appropriate use of contraception also should be offered to patients using retinoids. It is advisable to consider the use of combination oral contraceptives, particularly in women who have adult-onset acne or experience flare-ups around the time of their menstrual cycle.3

Azelaic acid has anticomedonal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties and may be effective in treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne and hyperpigmentation. Salicylic acid also has comedolytic properties, although there have been limited studies examining its effectiveness. Both azelaic and salicylic acid are considered safe for use in pregnancy.

Oral antibiotics are recommended in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. Both doxycycline and minocycline are more effective than tetracycline for treating acne, with no clear superiority between the two.4 Macrolides also can be effective in treating acne, although their use should be limited to those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines. Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to 3 to 4 months due to decreasing efficacy over time and to minimize the development of bacterial resistance. If treatment goals are attained, the antibiotics can be replaced with retinoids.

Oral isotretinoin is reserved for treatment of severe nodular acne or moderate acne that is treatment resistant. Patients should be counseled on contraceptive methods, as isotretinoin is highly teratogenic and therefore prescribed through the iPLEDGE program.3,4

Given this patient’s persistent symptoms despite use of topical antibiotics and topical tretinoin, she decided to try oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for 3 months and to start long-term oral contraceptives. If her symptoms continue, she will enroll in the iPLEDGE program and start treatment with oral isotretinoin.

Photo courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD. Text courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

2. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

3. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

4. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

1. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

2. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

3. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

4. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

Painful heels

This patient was given a diagnosis of xerosis of the feet, commonly called fissured or cracked heels. Scaling and fissuring are also common in tinea pedis, but the location is often between the toes and there are finer splits and scale.

Xerosis is severely dry skin with hyperkeratosis due to abnormal keratinization;1 it leads to inflexibility and subsequent fissuring of the heel pads. The cracks can be painful and even bleed.

Although the condition is common, well-controlled trials and definitive evidence in the literature are sparse. The authors of one systematic review were unable to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy of various treatments due to wide variation in research methodologies and outcome measures; they did, however, note that urea-containing products (followed by ammonium lactate products) were studied the most.2

In clinical practice, frequently applied topical emollients are recommended. Exfoliating products, including prescription Lac-Hydrin (ammonium lactate 12% cream) and the over-the-counter version, Am-Lactin, may be helpful. Mechanical debridement with a file or pumice stone can be used (with caution) to reduce the hyperkeratotic plaques. If these measures fail, topical steroids may be added to the emollients. In addition, patients have used cyanoacrylate glues to hold the fissures together with a reported reduction in pain.3

This patient had already tried standard topical emollients. She was prescribed ammonium lactate cream to be used as an exfoliating moisturizer topically twice daily along with triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) 0.1% ointment to be applied twice daily. She was instructed to wean off the TAC once the xerosis was controlled with the ammonium lactate cream.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Mazereeuw J, Bonafé JL. La xérose [Xerosis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129(1 Pt 2):137-142

2. Parker J, Scharfbillig R, Jones S. Moisturisers for the treatment of foot xerosis: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2017;10:9. doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0190-9

3. Hashimoto H. Superglue for the treatment of heel fissures. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:434-435. doi: 10.7547/87507315-89-8-434

This patient was given a diagnosis of xerosis of the feet, commonly called fissured or cracked heels. Scaling and fissuring are also common in tinea pedis, but the location is often between the toes and there are finer splits and scale.

Xerosis is severely dry skin with hyperkeratosis due to abnormal keratinization;1 it leads to inflexibility and subsequent fissuring of the heel pads. The cracks can be painful and even bleed.

Although the condition is common, well-controlled trials and definitive evidence in the literature are sparse. The authors of one systematic review were unable to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy of various treatments due to wide variation in research methodologies and outcome measures; they did, however, note that urea-containing products (followed by ammonium lactate products) were studied the most.2

In clinical practice, frequently applied topical emollients are recommended. Exfoliating products, including prescription Lac-Hydrin (ammonium lactate 12% cream) and the over-the-counter version, Am-Lactin, may be helpful. Mechanical debridement with a file or pumice stone can be used (with caution) to reduce the hyperkeratotic plaques. If these measures fail, topical steroids may be added to the emollients. In addition, patients have used cyanoacrylate glues to hold the fissures together with a reported reduction in pain.3

This patient had already tried standard topical emollients. She was prescribed ammonium lactate cream to be used as an exfoliating moisturizer topically twice daily along with triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) 0.1% ointment to be applied twice daily. She was instructed to wean off the TAC once the xerosis was controlled with the ammonium lactate cream.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This patient was given a diagnosis of xerosis of the feet, commonly called fissured or cracked heels. Scaling and fissuring are also common in tinea pedis, but the location is often between the toes and there are finer splits and scale.

Xerosis is severely dry skin with hyperkeratosis due to abnormal keratinization;1 it leads to inflexibility and subsequent fissuring of the heel pads. The cracks can be painful and even bleed.

Although the condition is common, well-controlled trials and definitive evidence in the literature are sparse. The authors of one systematic review were unable to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy of various treatments due to wide variation in research methodologies and outcome measures; they did, however, note that urea-containing products (followed by ammonium lactate products) were studied the most.2

In clinical practice, frequently applied topical emollients are recommended. Exfoliating products, including prescription Lac-Hydrin (ammonium lactate 12% cream) and the over-the-counter version, Am-Lactin, may be helpful. Mechanical debridement with a file or pumice stone can be used (with caution) to reduce the hyperkeratotic plaques. If these measures fail, topical steroids may be added to the emollients. In addition, patients have used cyanoacrylate glues to hold the fissures together with a reported reduction in pain.3

This patient had already tried standard topical emollients. She was prescribed ammonium lactate cream to be used as an exfoliating moisturizer topically twice daily along with triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) 0.1% ointment to be applied twice daily. She was instructed to wean off the TAC once the xerosis was controlled with the ammonium lactate cream.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Mazereeuw J, Bonafé JL. La xérose [Xerosis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129(1 Pt 2):137-142

2. Parker J, Scharfbillig R, Jones S. Moisturisers for the treatment of foot xerosis: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2017;10:9. doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0190-9

3. Hashimoto H. Superglue for the treatment of heel fissures. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:434-435. doi: 10.7547/87507315-89-8-434

1. Mazereeuw J, Bonafé JL. La xérose [Xerosis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129(1 Pt 2):137-142

2. Parker J, Scharfbillig R, Jones S. Moisturisers for the treatment of foot xerosis: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2017;10:9. doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0190-9

3. Hashimoto H. Superglue for the treatment of heel fissures. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:434-435. doi: 10.7547/87507315-89-8-434

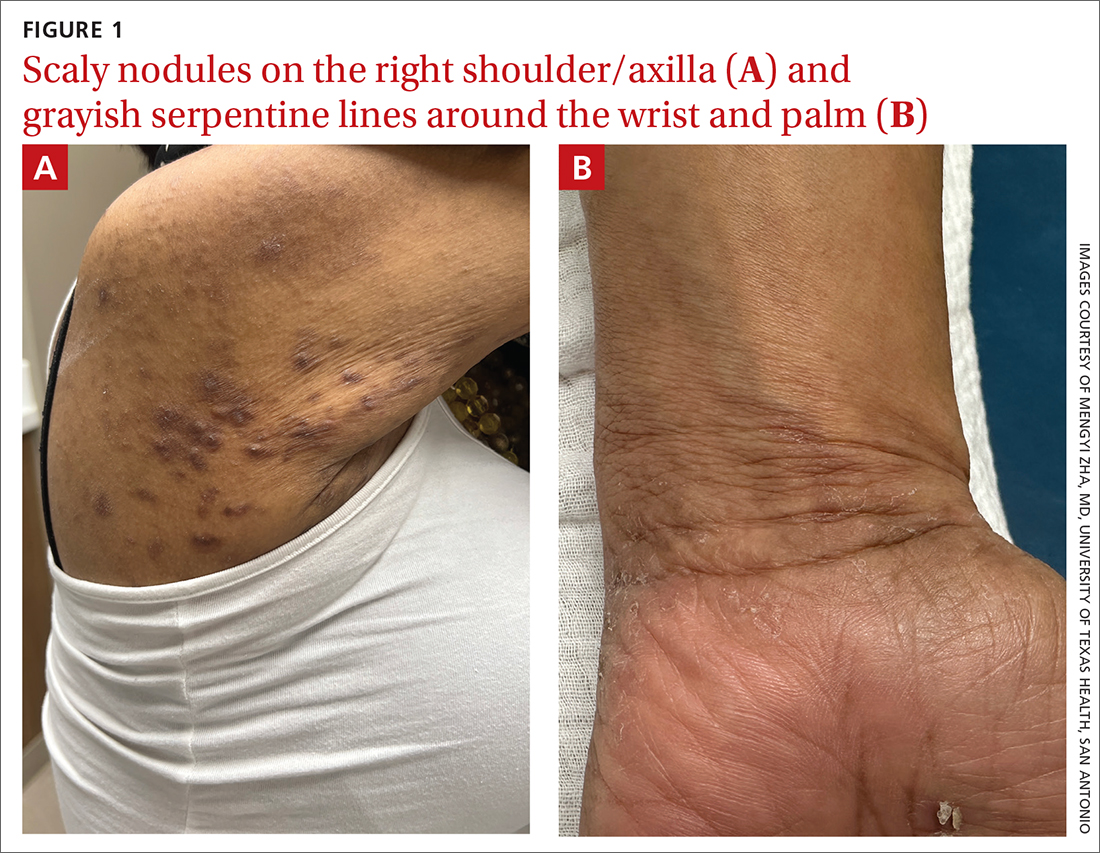

Pruritic rash and nocturnal itching

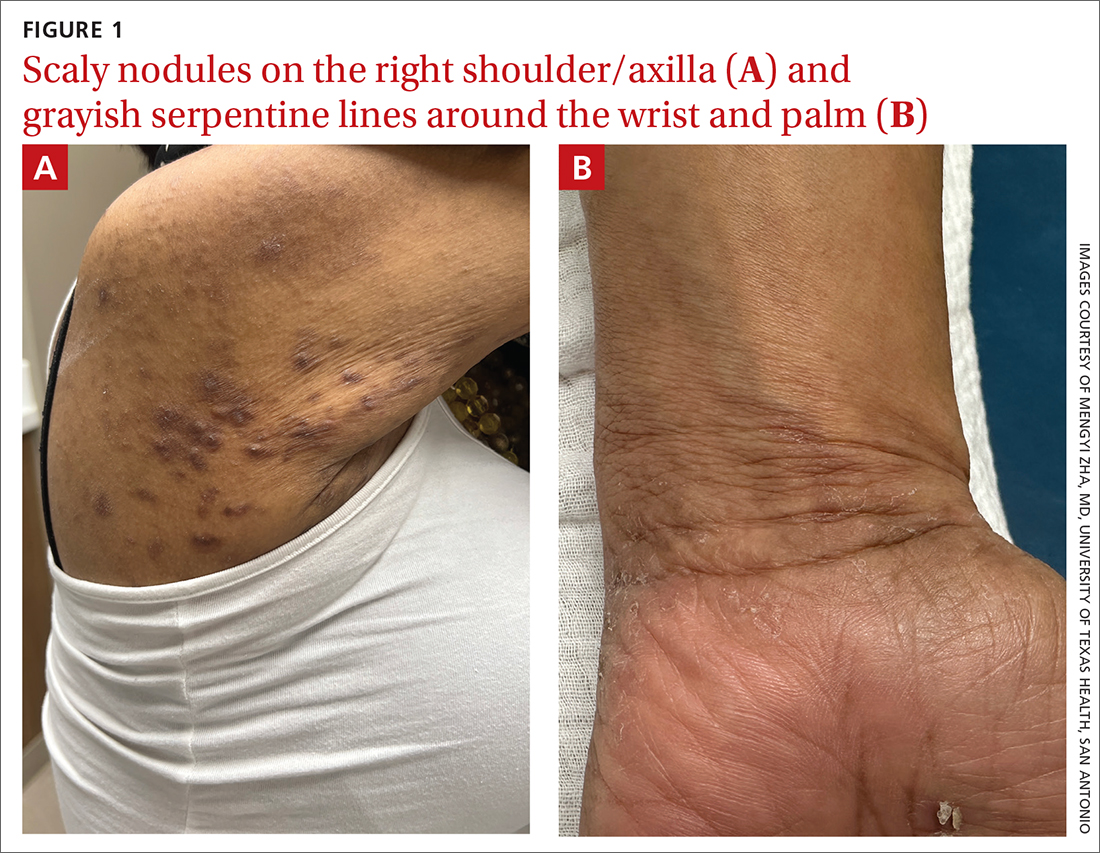

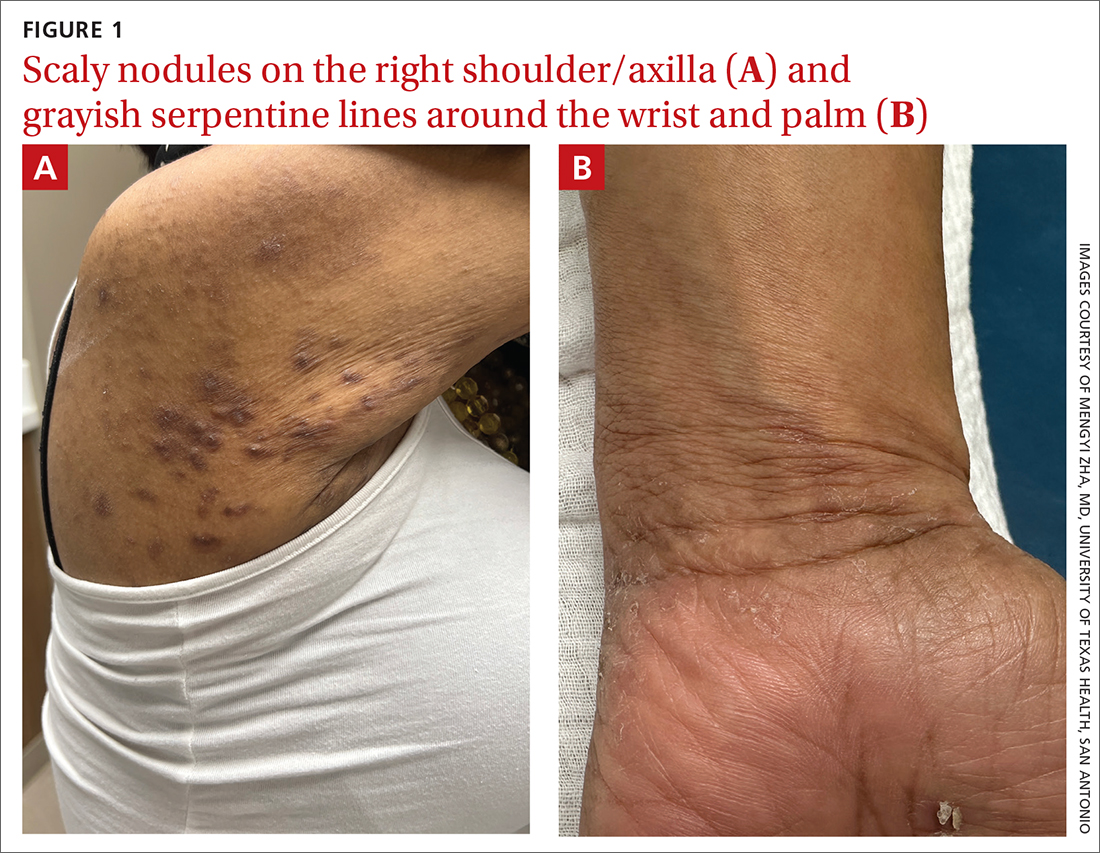

A 62-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC WOMAN with a history of well-controlled diabetes and hypertension presented with an intensely pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration. She reported poor sleep due to scratching throughout the night. She denied close contact with individuals with similar rashes or itching, new intimate partners, or recent travel. She worked in an office setting and had stable, noncrowded housing.

A physical exam revealed brown and purple scaly papules and many excoriation marks. The rash was concentrated along clothing lines, around intertriginous areas, and on her ankles, wrists, and the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scabies

Scabies is a diagnosis that should be considered in any patient with new-onset, widespread, nocturnal-dominant pruritus1 and it was suspected, in this case, after the initial history taking and physical exam. (See “Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions” for more on lichen planus and prurigo nodularis, which were also included in the differential diagnosis.)

SIDEBAR

Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that mostly affects the skin and mucosa. Characteristic findings are groups of shiny, flat-topped, firm papules. This patient’s widespread nodular lesions with rough scales were not typical of lichen planus, which usually manifests with flat (hence the name “planus”) and shiny lesions.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition that manifests as intensely itchy, firm papules. The lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but more commonly are found on the extremities, back, and torso. The recent manifestation of the patient’s lesions and her lack of a history of chronic dermatitis argued against this diagnosis.

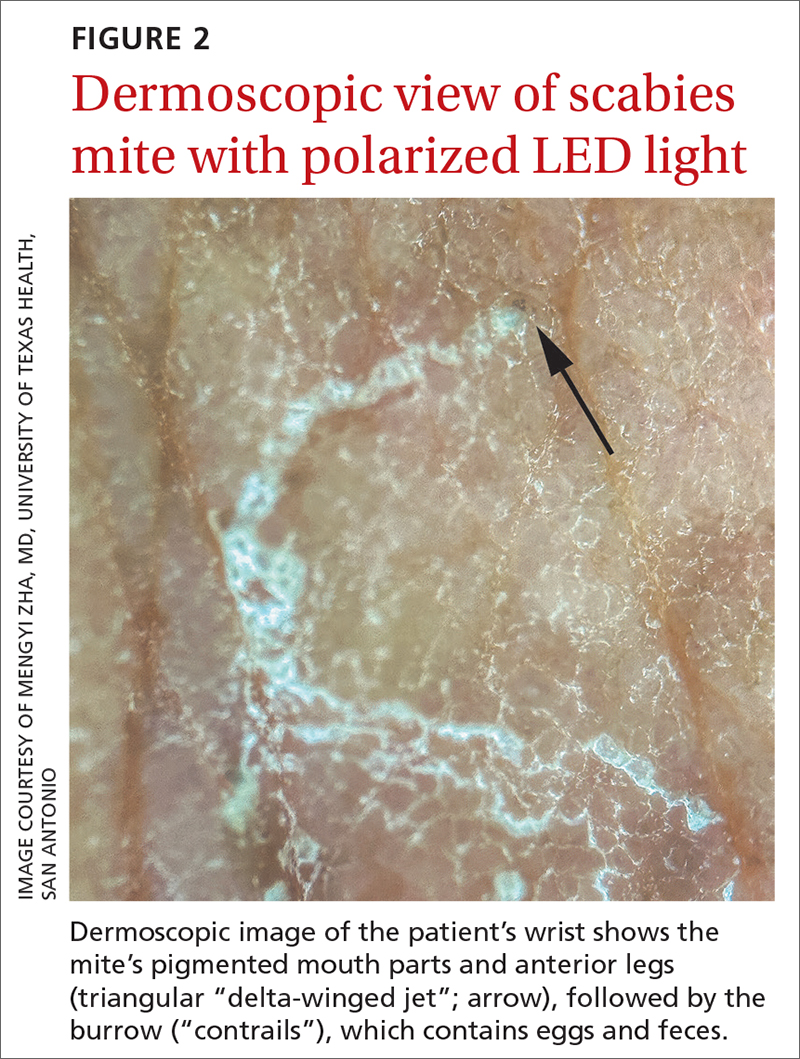

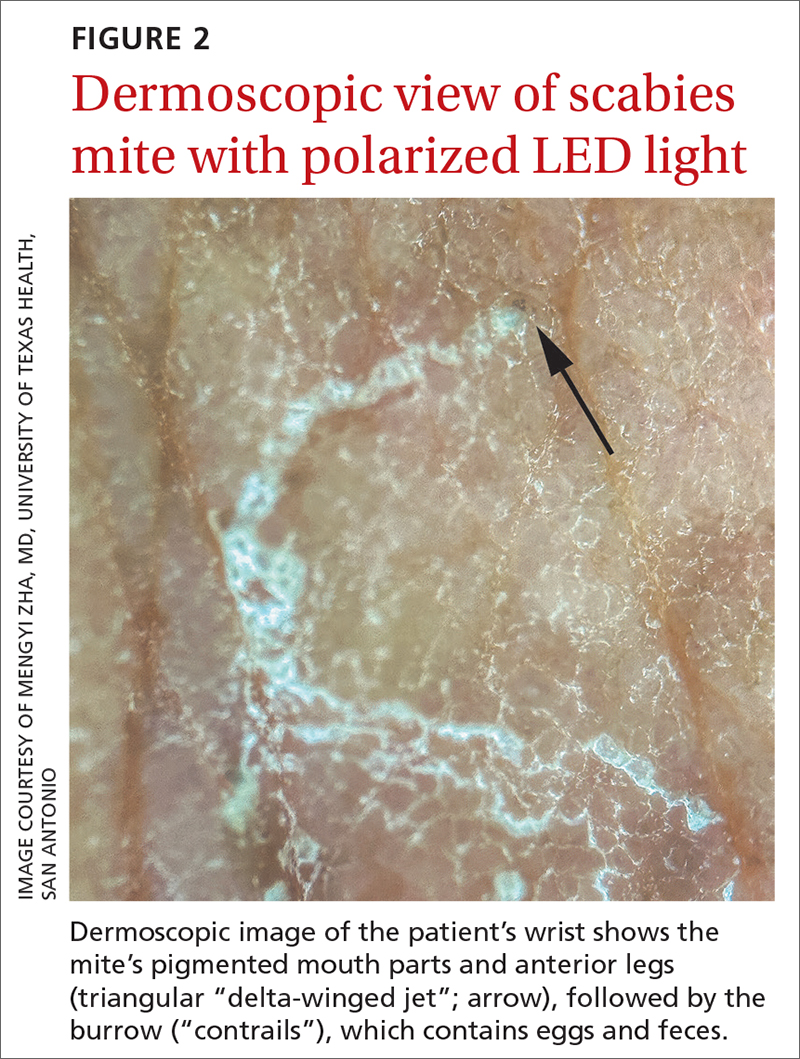

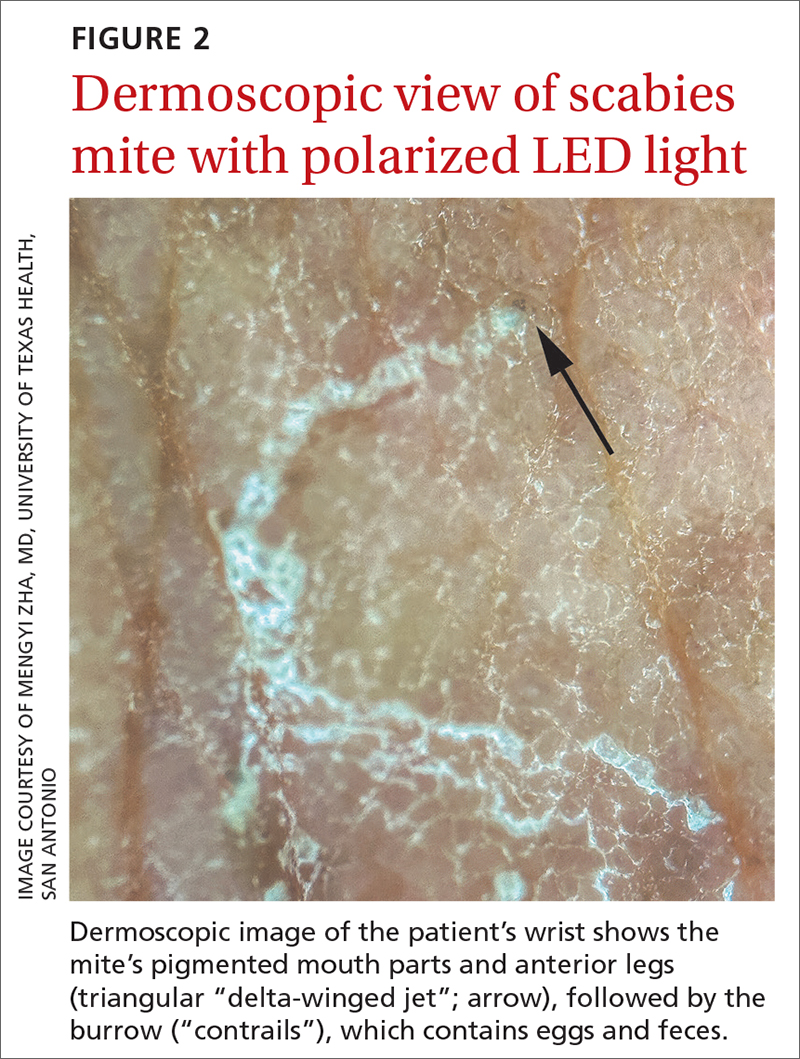

The use of a handheld dermatoscope confirmed the diagnosis by revealing white to yellow scales following the serpiginous lines. These serpiginous lines resembled scabies burrows, and at the end of some burrows, small triangular and hyperpigmented structures resembling “delta-winged jets” were seen. These “delta-winged jets” were the mite’s pigmented mouth parts and anterior legs. The burrows, which contain eggs and feces, have been described as the “contrails” behind the jets (FIGURE 2).

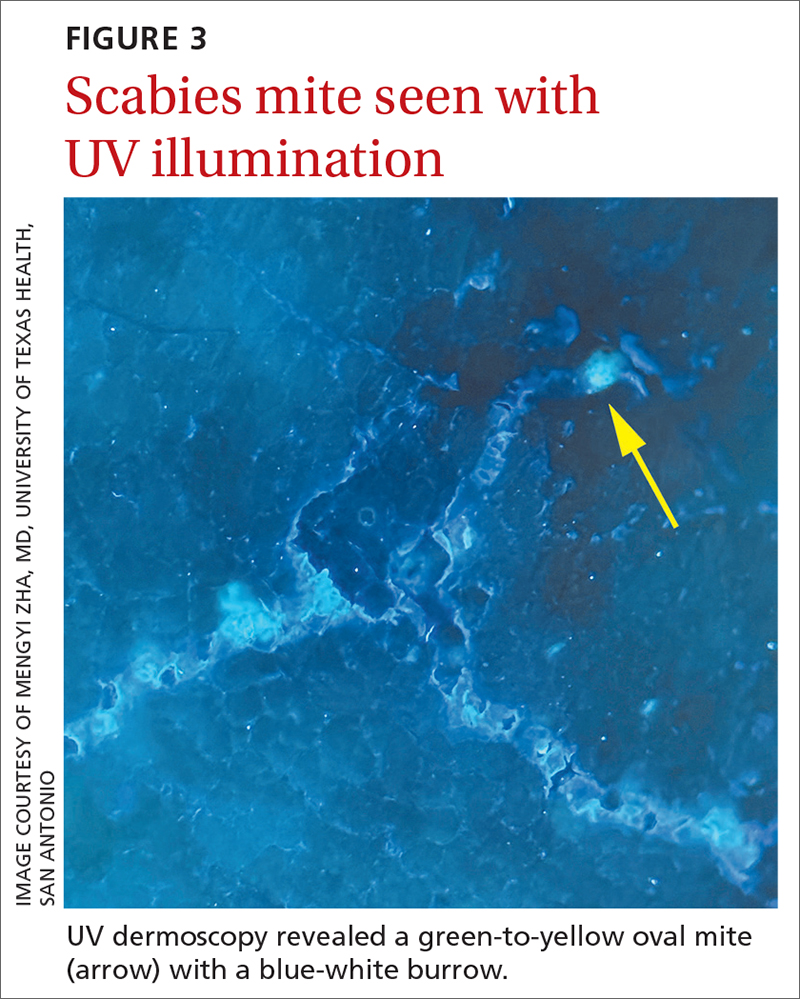

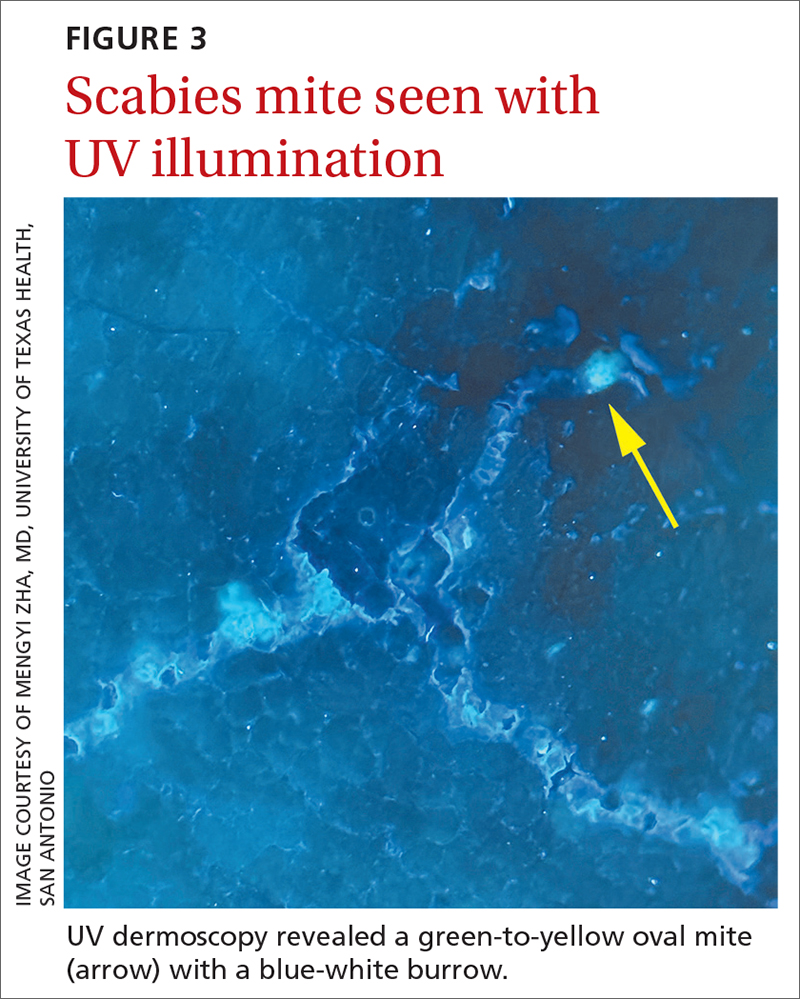

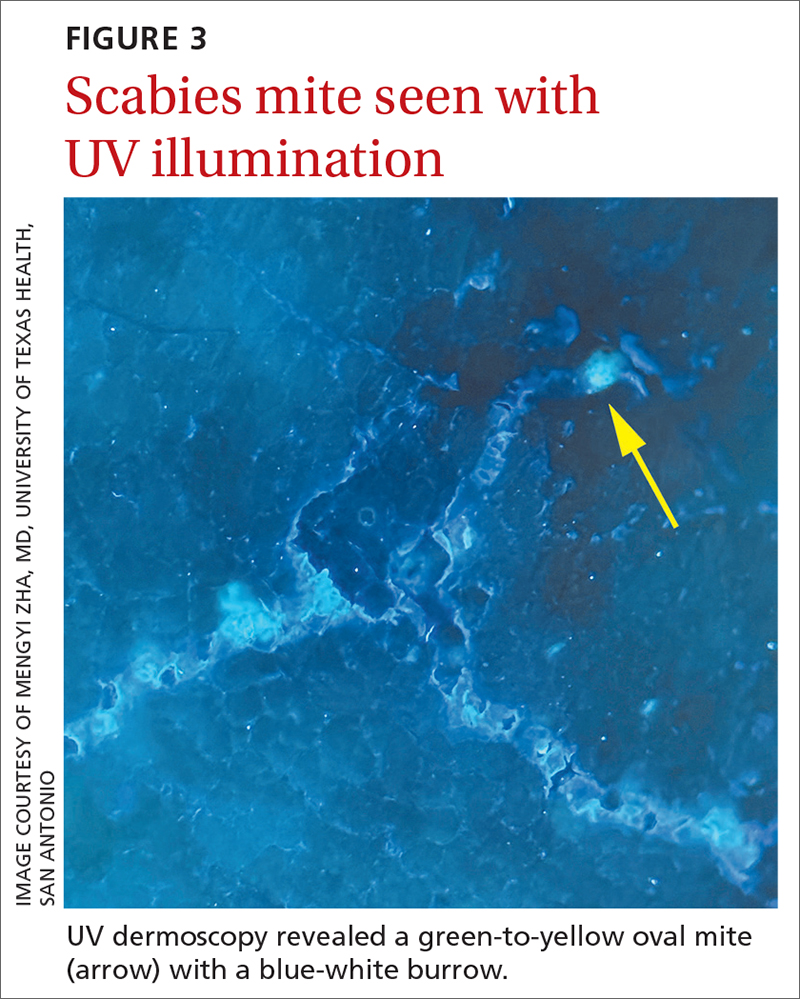

The use of a new UV illumination feature on our dermatoscope (which we’ll describe shortly) made for an even more dramatic diagnostic visual. With the click of a button, the mites fluoresced green to yellow and the burrows fluoresced white to blue (FIGURE 3).

Meeting the criteria. The clinical and dermoscopic findings met the 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies (IACS) Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies,2 confirming the diagnosis in this patient. Scabies infestation poses a significant public health burden globally, with an estimated incidence of more than 454 million in 2016.3

Visualization is key to the diagnosis

Traditionally, the diagnosis of scabies infestation is made by direct visualization of mites via microscopy of skin scrapings.4 However, this approach is seldom feasible in a family medicine office. Fortunately, the 2020 IACS criteria included dermoscopy as a Level A diagnostic method for confirmed scabies.

Continue to: The pros and cons of dermoscopy

The pros and cons of dermoscopy. A handheld dermatoscope is an accessible, convenient tool for any clinician who treats the skin. It has been demonstrated that, in the hands of experts and novices alike, dermoscopy has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 86% for the diagnosis of scabies.5

However, accurate identification of the dermoscopic findings can depend on the operator and can be harder to achieve in patients who have skin of color.2 This is largely because the mite’s brown-to-black triangular head is small (sometimes hidden under skin scales) and easy to miss, especially against darker skin.

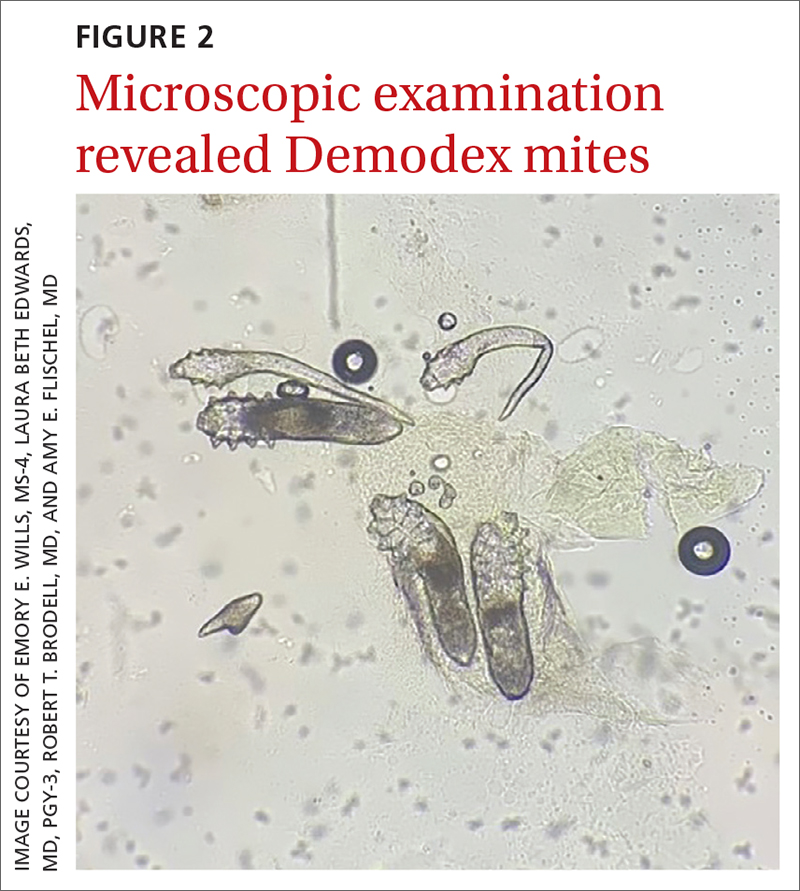

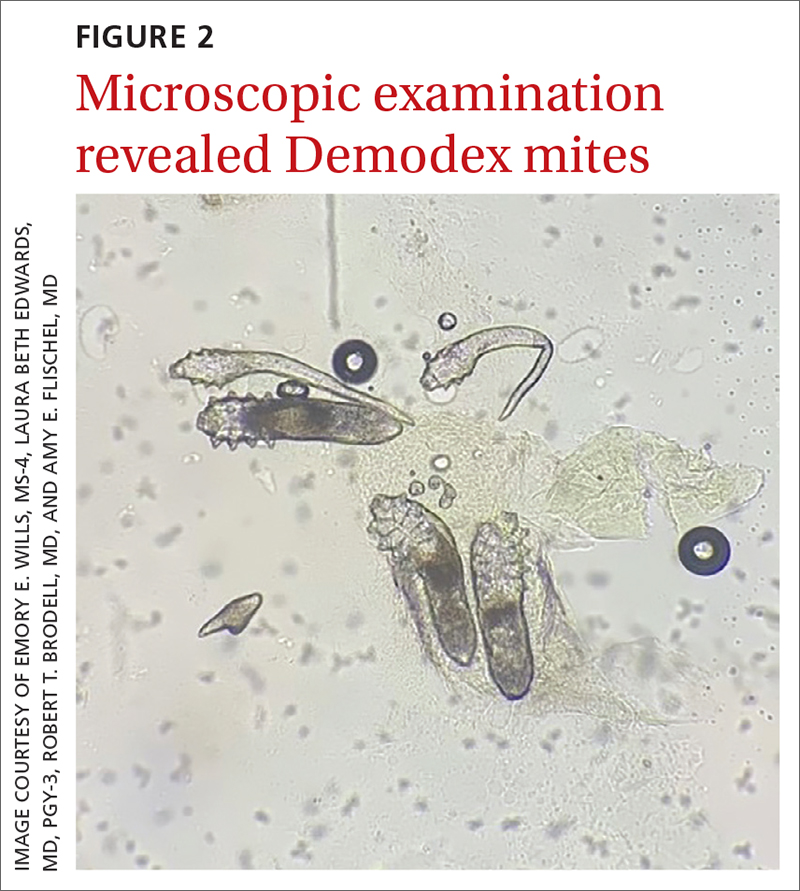

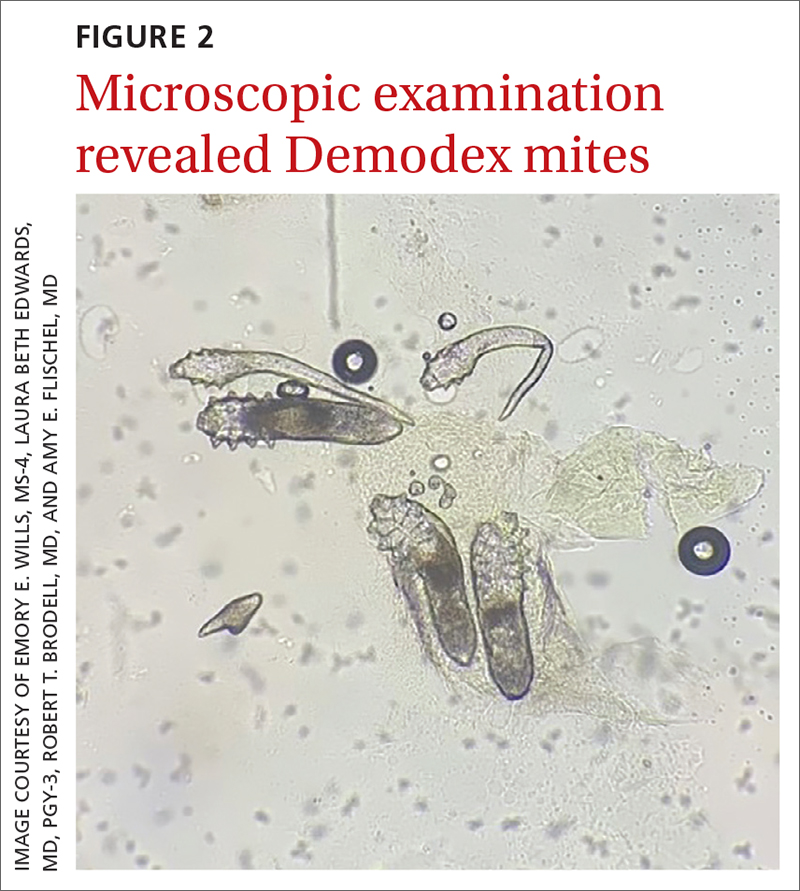

A new technologic feature helps. In this case, we used the built-in 365-nm UV illumination feature of our handheld dermatoscope (Dermlite-5) and both mites and burrows fluoresced intensely (FIGURE 3). A skin scraping at the location of the fluorescent body under microscopic examination confirmed that the organism was a Sarcoptes scabiei mite (FIGURE 4).

UV light dermoscopy can decrease operator error and ameliorate the challenge of diagnosing scabies in skin of color. Specifically, when using UV dermoscopy it’s easier to:

- locate mites, regardless of the patient’s skin color

- see the mite’s entire body, rather than just a small portion (thus increasing diagnostic certainty).

New diagnostic feature, classic treatment

Due to the severity of the patient’s scabies, she was prescribed both permethrin 5% cream and oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg, both to be used immediately and repeated in 1 week. Notably, a systematic review indicated that topical permethrin is a superior treatment to oral ivermectin.6 However, in cases of widespread scabies and crusted scabies, it is standard of care to treat with both medications.

The patient’s pruritus was treated with cetirizine as needed. She was told that the itching might persist for a few weeks after treatment was completed.

Reinfestation was a concern with this patient because she was unable to identify a source for the mites. To minimize the likelihood of reinfestation, we advised her to decontaminate her bedding, clothing, and towels by washing them in hot water (≥ 122° F) or placing in a sealed plastic bag for at least 1 week.1 For crusted scabies cases, thorough vacuuming of a patient’s furniture and carpets is recommended.

1. Gunning K, Kiraly B, Pippitt K. Lice and scabies: treatment update. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:635-642.

2. Engelman D, Yoshizumi J, Hay RJ, et al. The 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:808-820. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18943

A 62-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC WOMAN with a history of well-controlled diabetes and hypertension presented with an intensely pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration. She reported poor sleep due to scratching throughout the night. She denied close contact with individuals with similar rashes or itching, new intimate partners, or recent travel. She worked in an office setting and had stable, noncrowded housing.

A physical exam revealed brown and purple scaly papules and many excoriation marks. The rash was concentrated along clothing lines, around intertriginous areas, and on her ankles, wrists, and the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scabies