User login

Not acne, but what?

AN OTHERWISE HEALTHY

Scattered papules and pustules were present on the forehead, nose, and cheeks, with background erythema and telangiectasias (FIGURE 1). A few pinpoint crusted excoriations were noted. A sample was taken from the papules and pustules using a #15 blade and submitted for examination.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rosacea with Demodex mites

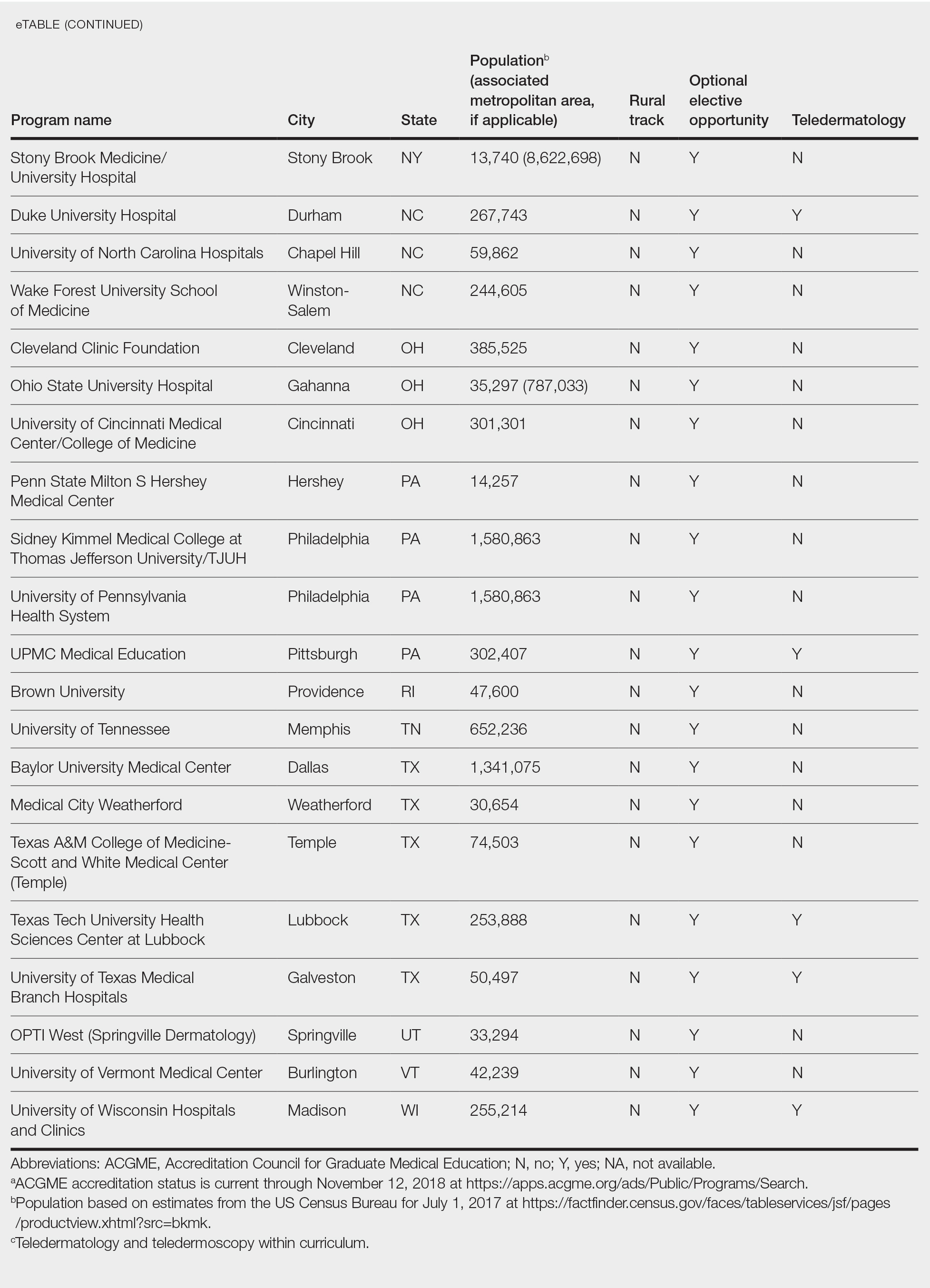

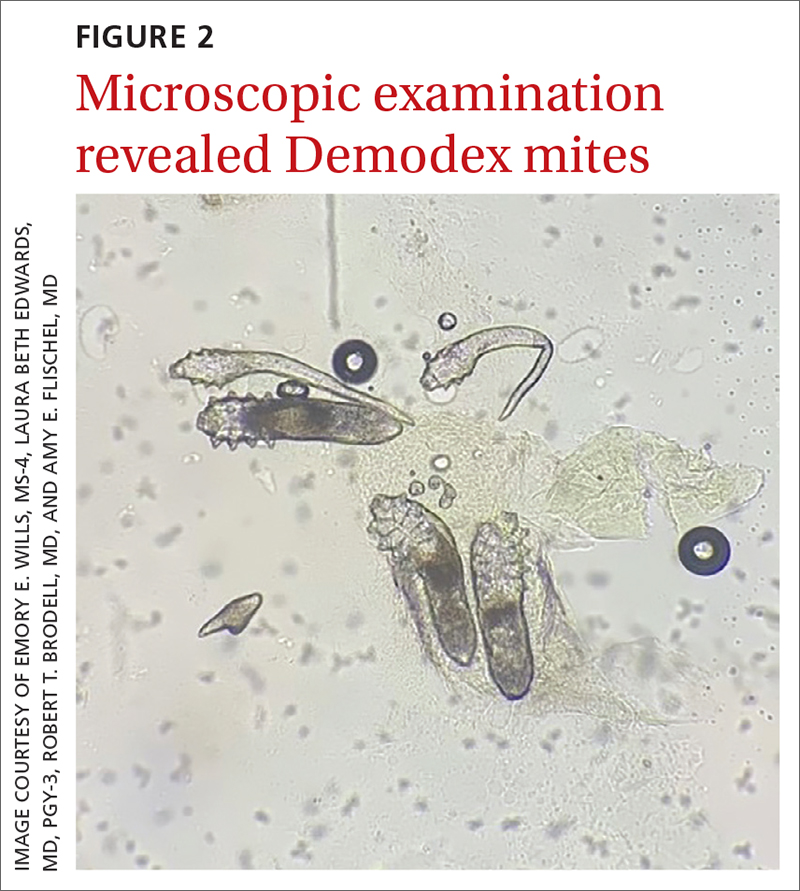

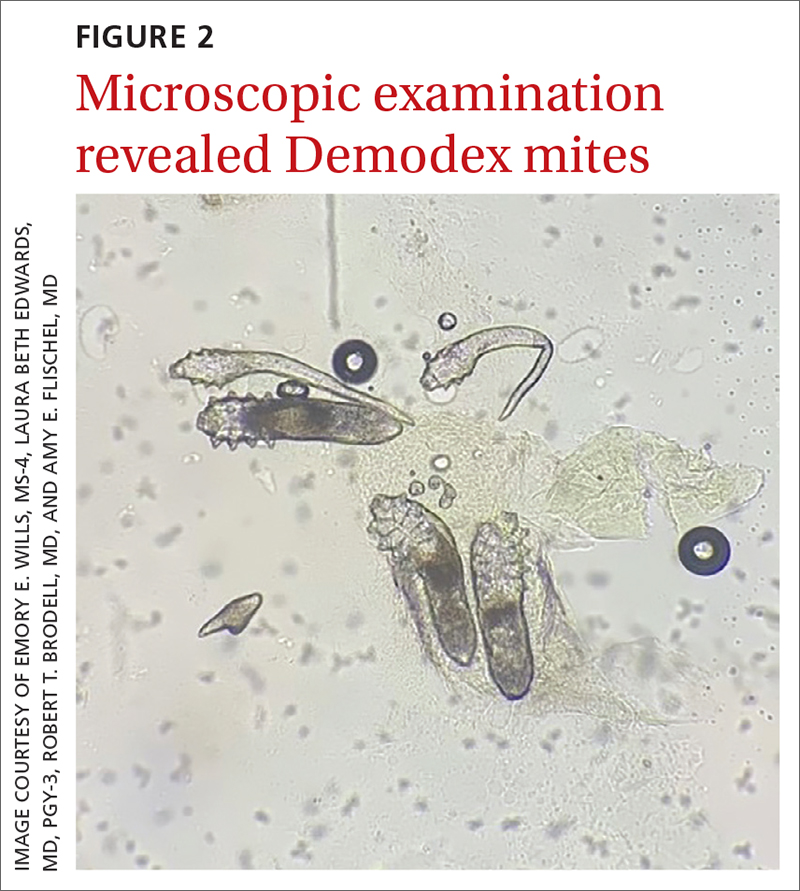

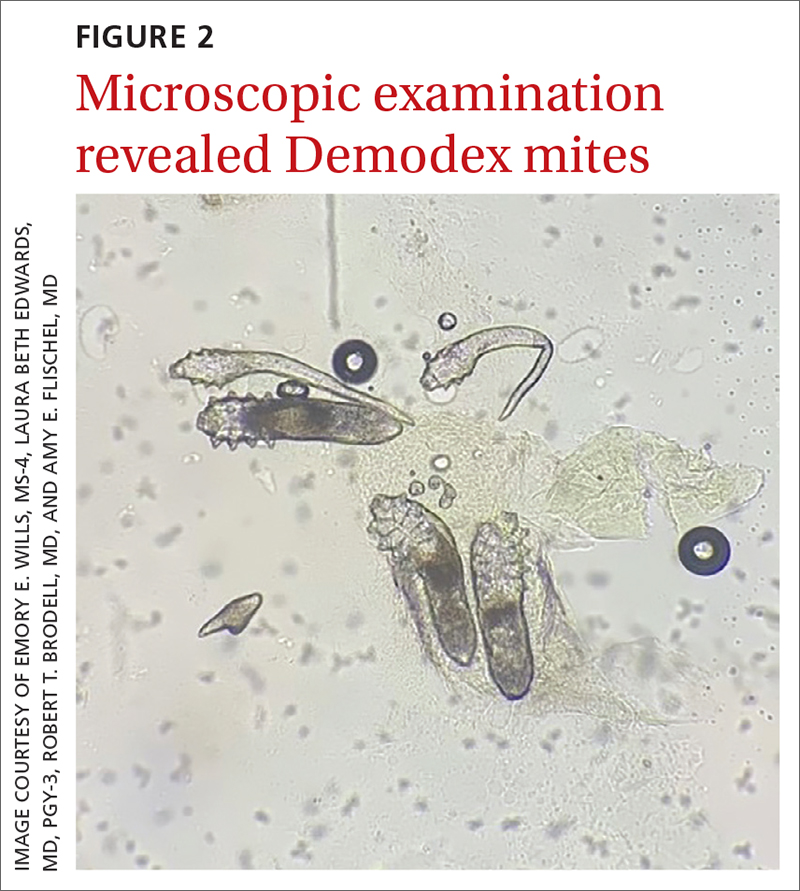

Under light microscopy, the scraping revealed Demodex mites (FIGURE 2). It has been proposed that these mites play a role in the inflammatory process seen in rosacea, although studies have yet to determine whether the inflammatory symptoms of rosacea cause the mites to proliferate or if the mites contribute to the initial inflammatory process.1,2

Demodex folliculorum and D brevis are part of normal skin flora; they are found in about 12% of all follicles and most commonly involve the face.3 They often become abundant in the presence of numerous sebaceous glands. Men have more sebaceous glands than women do, and thus run a greater risk for infestation with mites. An abnormal proliferation of Demodex mites can lead to demodicosis.

Demodex mites can be examined microscopically via the skin surface sampling technique known as scraping, which was done in this case. Samples taken from the papules and pustules utilizing a #15 blade are placed in immersion oil on a glass slide, cover-slipped, and examined by light microscopy.

Rosacea is thought to be an inflammatory disease in which the immune system is triggered by a variety of factors, including UV light, heat, stress, alcohol, hormonal influences, and microorganisms.1,4 The disease is found in up to 10% of the population worldwide.1

The diagnosis of rosacea requires at least 1 of the 2 “core features”—persistent central facial erythema or phymatous changes—or 2 of 4 “major features”: papules/pustules, ocular manifestation, flushing, and telangiectasias. There are 3 phenotypes: ocular, papulopustular, and erythematotelangiectatic.5,6

Continue to: The connection

The connection. Papulopustular and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea may be caused by a proliferation of Demodex mites and increased vascular endothelial growth factor production.2 In fact, a proliferation of Demodex is seen in almost all cases of papulopustular rosacea and more than 60% of cases of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.2

Patient age and distribution of lesions narrowed the differential

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units caused by increased sebum production, inflammation, and bacterial colonization (Propionibacterium acnes) of hair follicles on the face, neck, chest, and other areas. Both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions can be present, and in serious cases, scarring can result.7 The case patient’s age and accompanying broad erythema were more consistent with rosacea than acne vulgaris.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition usually stemming from an inflammatory reaction to a common yeast. Classic symptoms include scaling and erythema of the scalp and central face, as well as pruritus. Topical antifungals such as ketoconazole 2% cream and 2% shampoo are the mainstay of treatment.8 The broad distribution and papulopustules in this patient argue against the diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a systemic inflammatory disease that often has cutaneous manifestations. Acute lupus manifests as an erythematous “butterfly rash” across the face and cheeks. Chronic discoid lupus involves depigmented plaques, erythematous macules, telangiectasias, and scarring with loss of normal hair follicles. These findings classically are photodistributed.9 The classic broad erythema extending from the cheeks over the bridge of the nose was not present in this patient.

Treatment is primarily topical

Mild cases of rosacea often can be managed with topical antibiotic creams. More severe cases may require systemic antibiotics such as tetracycline or doxycycline, although these are used with caution due to the potential for antibiotic resistance.

Ivermectin 1% cream is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved medication that is applied once daily for up to a year to treat the inflammatory pustules associated with Demodex mites. Although it is costly, studies have shown better results with topical ivermectin than with other topical medications (eg, metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream). However, metronidazole 0.75% gel applied twice daily and oral tetracycline 250 mg or doxycycline 100 mg daily or twice daily for at least 2 months often are utilized when the cost of topical ivermectin is prohibitive.10

Our patient was treated with a combination of doxycycline 100 mg daily for 30 days and

1. Forton FMN. Rosacea, an infectious disease: why rosacea with papulopustules should be considered a demodicosis. A narrative review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:987-1002. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18049

2. Forton FMN. The pathogenic role of demodex mites in rosacea: a potential therapeutic target already in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea? Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:1229-1253. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00458-9

3. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.006

4. Erbağci Z, OzgöztaŞi O. The significance of demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421-425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00218.x

5. Tan J, Almeida LMC, Criber B, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:431-438. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122

6. Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.037

7. Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:361-372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8.

8. Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:185-190.

9. Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:355-362.

10. Raedler LA. Soolantra (ivermectin) 1% cream: a novel, antibiotic-free agent approved for the treatment of patients with rosacea. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(Spec Feature):122-125.

AN OTHERWISE HEALTHY

Scattered papules and pustules were present on the forehead, nose, and cheeks, with background erythema and telangiectasias (FIGURE 1). A few pinpoint crusted excoriations were noted. A sample was taken from the papules and pustules using a #15 blade and submitted for examination.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rosacea with Demodex mites

Under light microscopy, the scraping revealed Demodex mites (FIGURE 2). It has been proposed that these mites play a role in the inflammatory process seen in rosacea, although studies have yet to determine whether the inflammatory symptoms of rosacea cause the mites to proliferate or if the mites contribute to the initial inflammatory process.1,2

Demodex folliculorum and D brevis are part of normal skin flora; they are found in about 12% of all follicles and most commonly involve the face.3 They often become abundant in the presence of numerous sebaceous glands. Men have more sebaceous glands than women do, and thus run a greater risk for infestation with mites. An abnormal proliferation of Demodex mites can lead to demodicosis.

Demodex mites can be examined microscopically via the skin surface sampling technique known as scraping, which was done in this case. Samples taken from the papules and pustules utilizing a #15 blade are placed in immersion oil on a glass slide, cover-slipped, and examined by light microscopy.

Rosacea is thought to be an inflammatory disease in which the immune system is triggered by a variety of factors, including UV light, heat, stress, alcohol, hormonal influences, and microorganisms.1,4 The disease is found in up to 10% of the population worldwide.1

The diagnosis of rosacea requires at least 1 of the 2 “core features”—persistent central facial erythema or phymatous changes—or 2 of 4 “major features”: papules/pustules, ocular manifestation, flushing, and telangiectasias. There are 3 phenotypes: ocular, papulopustular, and erythematotelangiectatic.5,6

Continue to: The connection

The connection. Papulopustular and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea may be caused by a proliferation of Demodex mites and increased vascular endothelial growth factor production.2 In fact, a proliferation of Demodex is seen in almost all cases of papulopustular rosacea and more than 60% of cases of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.2

Patient age and distribution of lesions narrowed the differential

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units caused by increased sebum production, inflammation, and bacterial colonization (Propionibacterium acnes) of hair follicles on the face, neck, chest, and other areas. Both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions can be present, and in serious cases, scarring can result.7 The case patient’s age and accompanying broad erythema were more consistent with rosacea than acne vulgaris.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition usually stemming from an inflammatory reaction to a common yeast. Classic symptoms include scaling and erythema of the scalp and central face, as well as pruritus. Topical antifungals such as ketoconazole 2% cream and 2% shampoo are the mainstay of treatment.8 The broad distribution and papulopustules in this patient argue against the diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a systemic inflammatory disease that often has cutaneous manifestations. Acute lupus manifests as an erythematous “butterfly rash” across the face and cheeks. Chronic discoid lupus involves depigmented plaques, erythematous macules, telangiectasias, and scarring with loss of normal hair follicles. These findings classically are photodistributed.9 The classic broad erythema extending from the cheeks over the bridge of the nose was not present in this patient.

Treatment is primarily topical

Mild cases of rosacea often can be managed with topical antibiotic creams. More severe cases may require systemic antibiotics such as tetracycline or doxycycline, although these are used with caution due to the potential for antibiotic resistance.

Ivermectin 1% cream is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved medication that is applied once daily for up to a year to treat the inflammatory pustules associated with Demodex mites. Although it is costly, studies have shown better results with topical ivermectin than with other topical medications (eg, metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream). However, metronidazole 0.75% gel applied twice daily and oral tetracycline 250 mg or doxycycline 100 mg daily or twice daily for at least 2 months often are utilized when the cost of topical ivermectin is prohibitive.10

Our patient was treated with a combination of doxycycline 100 mg daily for 30 days and

AN OTHERWISE HEALTHY

Scattered papules and pustules were present on the forehead, nose, and cheeks, with background erythema and telangiectasias (FIGURE 1). A few pinpoint crusted excoriations were noted. A sample was taken from the papules and pustules using a #15 blade and submitted for examination.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rosacea with Demodex mites

Under light microscopy, the scraping revealed Demodex mites (FIGURE 2). It has been proposed that these mites play a role in the inflammatory process seen in rosacea, although studies have yet to determine whether the inflammatory symptoms of rosacea cause the mites to proliferate or if the mites contribute to the initial inflammatory process.1,2

Demodex folliculorum and D brevis are part of normal skin flora; they are found in about 12% of all follicles and most commonly involve the face.3 They often become abundant in the presence of numerous sebaceous glands. Men have more sebaceous glands than women do, and thus run a greater risk for infestation with mites. An abnormal proliferation of Demodex mites can lead to demodicosis.

Demodex mites can be examined microscopically via the skin surface sampling technique known as scraping, which was done in this case. Samples taken from the papules and pustules utilizing a #15 blade are placed in immersion oil on a glass slide, cover-slipped, and examined by light microscopy.

Rosacea is thought to be an inflammatory disease in which the immune system is triggered by a variety of factors, including UV light, heat, stress, alcohol, hormonal influences, and microorganisms.1,4 The disease is found in up to 10% of the population worldwide.1

The diagnosis of rosacea requires at least 1 of the 2 “core features”—persistent central facial erythema or phymatous changes—or 2 of 4 “major features”: papules/pustules, ocular manifestation, flushing, and telangiectasias. There are 3 phenotypes: ocular, papulopustular, and erythematotelangiectatic.5,6

Continue to: The connection

The connection. Papulopustular and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea may be caused by a proliferation of Demodex mites and increased vascular endothelial growth factor production.2 In fact, a proliferation of Demodex is seen in almost all cases of papulopustular rosacea and more than 60% of cases of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.2

Patient age and distribution of lesions narrowed the differential

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units caused by increased sebum production, inflammation, and bacterial colonization (Propionibacterium acnes) of hair follicles on the face, neck, chest, and other areas. Both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions can be present, and in serious cases, scarring can result.7 The case patient’s age and accompanying broad erythema were more consistent with rosacea than acne vulgaris.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition usually stemming from an inflammatory reaction to a common yeast. Classic symptoms include scaling and erythema of the scalp and central face, as well as pruritus. Topical antifungals such as ketoconazole 2% cream and 2% shampoo are the mainstay of treatment.8 The broad distribution and papulopustules in this patient argue against the diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a systemic inflammatory disease that often has cutaneous manifestations. Acute lupus manifests as an erythematous “butterfly rash” across the face and cheeks. Chronic discoid lupus involves depigmented plaques, erythematous macules, telangiectasias, and scarring with loss of normal hair follicles. These findings classically are photodistributed.9 The classic broad erythema extending from the cheeks over the bridge of the nose was not present in this patient.

Treatment is primarily topical

Mild cases of rosacea often can be managed with topical antibiotic creams. More severe cases may require systemic antibiotics such as tetracycline or doxycycline, although these are used with caution due to the potential for antibiotic resistance.

Ivermectin 1% cream is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved medication that is applied once daily for up to a year to treat the inflammatory pustules associated with Demodex mites. Although it is costly, studies have shown better results with topical ivermectin than with other topical medications (eg, metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream). However, metronidazole 0.75% gel applied twice daily and oral tetracycline 250 mg or doxycycline 100 mg daily or twice daily for at least 2 months often are utilized when the cost of topical ivermectin is prohibitive.10

Our patient was treated with a combination of doxycycline 100 mg daily for 30 days and

1. Forton FMN. Rosacea, an infectious disease: why rosacea with papulopustules should be considered a demodicosis. A narrative review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:987-1002. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18049

2. Forton FMN. The pathogenic role of demodex mites in rosacea: a potential therapeutic target already in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea? Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:1229-1253. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00458-9

3. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.006

4. Erbağci Z, OzgöztaŞi O. The significance of demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421-425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00218.x

5. Tan J, Almeida LMC, Criber B, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:431-438. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122

6. Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.037

7. Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:361-372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8.

8. Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:185-190.

9. Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:355-362.

10. Raedler LA. Soolantra (ivermectin) 1% cream: a novel, antibiotic-free agent approved for the treatment of patients with rosacea. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(Spec Feature):122-125.

1. Forton FMN. Rosacea, an infectious disease: why rosacea with papulopustules should be considered a demodicosis. A narrative review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:987-1002. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18049

2. Forton FMN. The pathogenic role of demodex mites in rosacea: a potential therapeutic target already in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea? Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:1229-1253. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00458-9

3. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.006

4. Erbağci Z, OzgöztaŞi O. The significance of demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421-425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00218.x

5. Tan J, Almeida LMC, Criber B, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:431-438. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122

6. Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.037

7. Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:361-372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8.

8. Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:185-190.

9. Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:355-362.

10. Raedler LA. Soolantra (ivermectin) 1% cream: a novel, antibiotic-free agent approved for the treatment of patients with rosacea. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(Spec Feature):122-125.

Facial Follicular Spicules: A Rare Cutaneous Presentation of Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and congestive heart failure presented with a disfiguring eruption comprised of asymptomatic papules on the face that appeared 12 months post–heart transplantation. Immunosuppressive medications included mycophenolic acid and tacrolimus ointment (FK506). The pinpoint papules spread from the central face to the ears, arms, and legs. Physical examination revealed multiple 0.5- to 1-mm flesh-colored papules over the glabella, nose, nasolabial folds, philtrum, chin, ears, arms, and legs sparing the trunk. The initial appearance of the facial rash resembled the surface of a nutmeg grater with central white spiny excrescences overlying fine papules (spinulosism)(Figure 1). In addition, eyebrow alopecia was present.

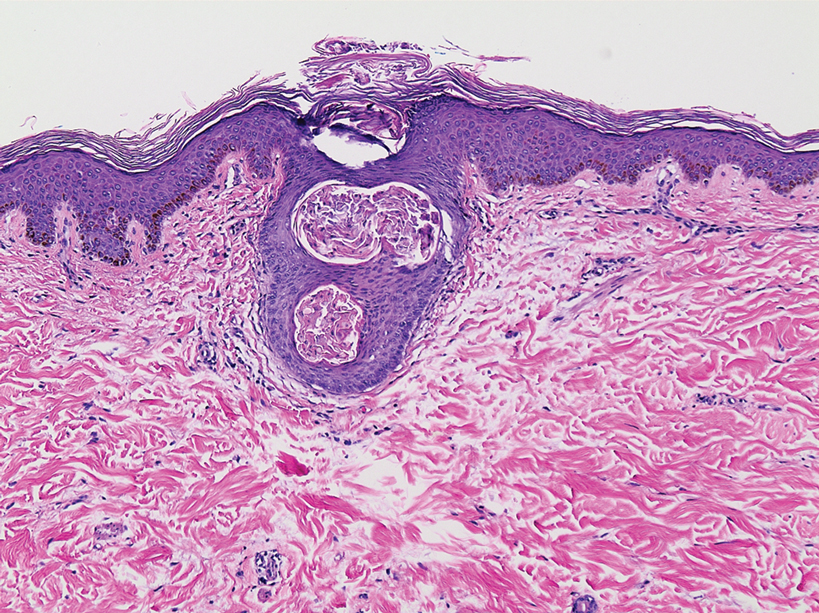

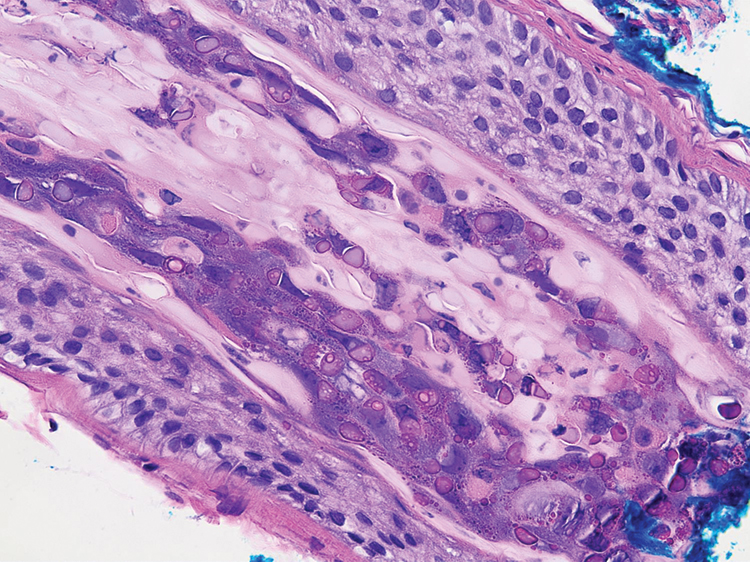

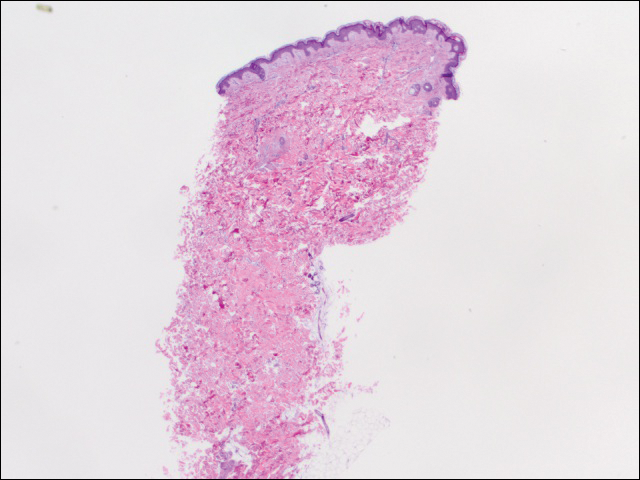

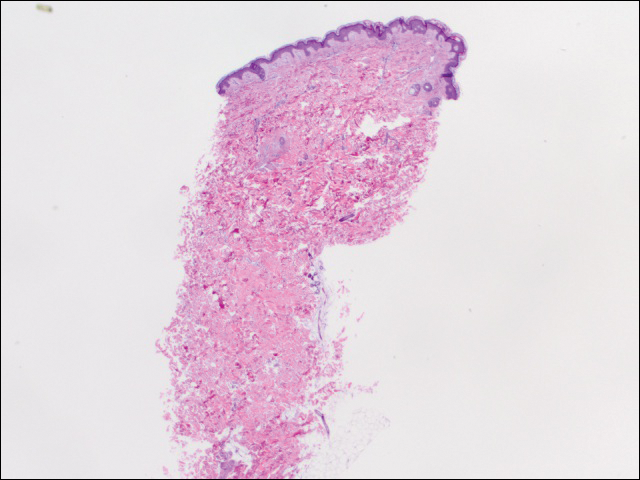

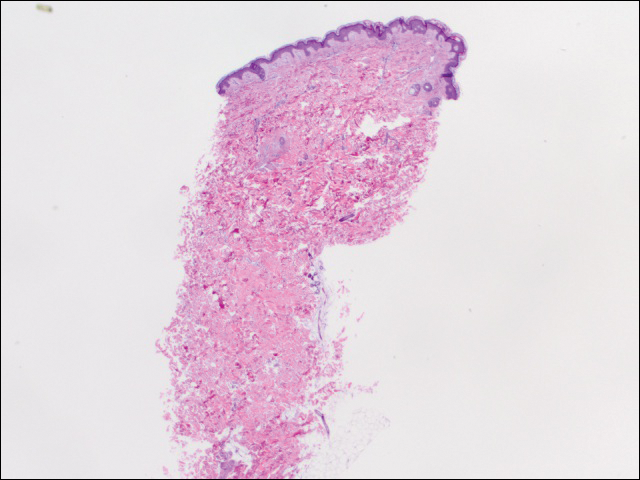

A 3-mm punch biopsy of a papule with a central spine was performed on the left thigh. Microscopic examination revealed marked dilatation of anagen hair follicles with a proliferation of haphazard inner root sheath cells replacing the follicular lumen. Hair shafts were absent, and plugged infundibula were observed (Figure 2). The inner root sheath keratinocytes were enlarged and dystrophic with deeply eosinophilic trichohyalin granules (Figure 3). The epidermis, outer root sheath epithelium, and eccrine structures were unremarkable.

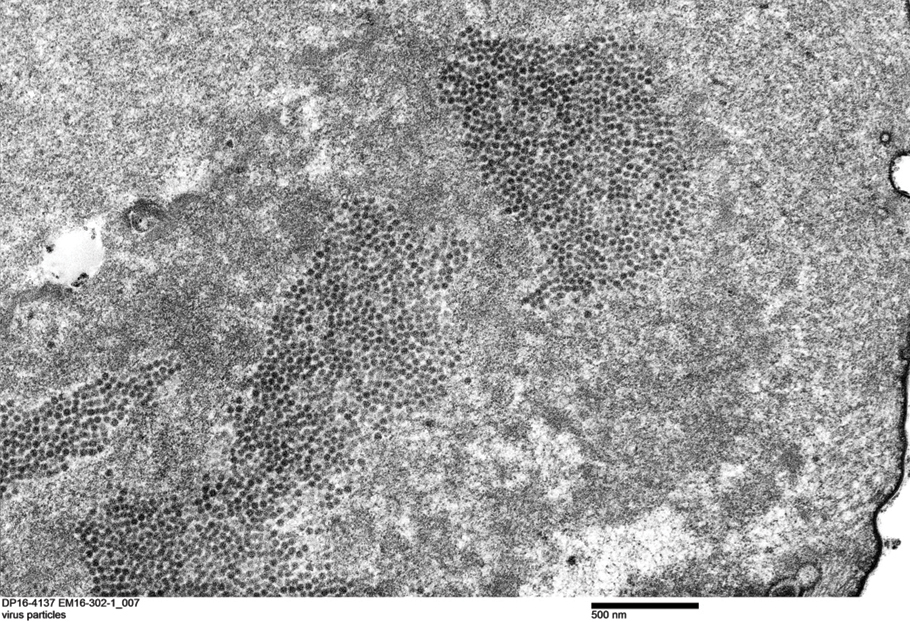

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed the presence of intranuclear viral inclusions within affected inner root sheath keratinocytes composed of nonenveloped icosahedral viral particles measuring 33 to 38 nm in diameter (Figure 4). These findings morphologically were consistent with a polyomavirus. No intracytoplasmic or extracellular viral particles were identified. The clinical history, physical examination, histopathology, and electron microscopy features strongly supported the diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) despite insufficient material being retrieved for polymerase chain reaction identification.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first described by Haycox et al1 in 1999. The authors suggested a viral etiology. Eleven years later, TS-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) was identified by van der Meijden et al.2 Follicular keratinocytes are the specific target for TSPyV.3 Evidence has been presented suggesting that TS is caused by a primary infection or reactivation of TSPyV in the setting of immunosuppression.4,5

Patients with TS present with papular eruptions that appear on the central face with spiny excrescences and various degrees of alopecia involving the eyebrows or eyelashes. Histopathologic features include distended hair follicles with expansion of inner root sheath cells, eosinophilic trichohyalin granules, and the absence of hair shafts. The viral protein can be verified through immunohistochemistry TSPyV VP1 staining that demonstrates co-localization with trichohyalin. Viral particles also can be visualized as 35- to 38-nm intranuclear particles with an organized crystalloid morphology on TEM.6,7 The negative polymerase chain reaction in our patient could be the result of suboptimal template DNA concentration extracted from the limited amount of tissue remaining in the block after hematoxylin and eosin staining.

The clinical differential diagnosis of central facial spinulosism includes the follicular spicules of multiple myeloma (FSMM). In fact, FSMM and TS can only be differentiated after obtaining a blood profile and bone marrow biopsy that excludes the diagnosis of FSMM. A history of immunosuppression typically suggests TS. Histopathology often is equivocal in FSMM8; however, TEM reveals viral particles (TSPyV) in TS. Transmission electron microscopy in FSMM demonstrates fibrillary structures arranged in a paracrystalline configuration with unknown significance instead of viral particles. Despite the absence of viral particles on TEM, a low mean copy number of Merkel cell polyomavirus was isolated from a patient with FSMM who responded dramatically to treatment with topical cidofovir gel 1%.8 In addition to treating the underlying multiple myeloma in FSMM, topical cidofovir gel 1% also may have a role in treatment of these patients, suggesting a possible viral rather than simply paraneoplastic etiology of FSMM. Therefore, polyomavirus infection should be considered in the initial workup of any patient with fine facial follicular spicules.

The most effective management of TS in transplant recipients is to reduce immunosuppression to the lowest level possible without jeopardizing the transplanted organ.9 In our case, reduction of immunosuppressive drugs was not possible. In fact, immunosuppression in our patient was increased following evidence of early rejection of the heart transplant. Although manual extraction of the keratin spicules resulted in considerable improvement in a similar facial eruption in a patient with pediatric pre–B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia developing TS,10 it is impossible to apply this approach to patients such as ours who have thousands of tiny lesions. Fortunately, custom-compounded cidofovir gel 1% applied twice daily to the patient’s face and ears for 4 weeks led to near-complete clearance at follow-up (Figure 5). Due to the high cost of the medication (approaching $700 for one tube), our patient applied this medication to the face only several times weekly with excellent improvement. Thus, it appears that it is possible to suppress this virus with topical medication alone.

Polyomavirus infection should be considered in patients presenting with fine follicular spiny papules, especially those who are immunosuppressed. The possibility of coexisting multiple myeloma should be excluded.

Acknowledgment—We sincerely thank Glenn A. Hoskins (Jackson, Mississippi), the electron microscopy technologist, for the detection of viral particles and the electron microscope photographs.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromized patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Rouanet J, Aubin F, Gaboriaud P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a polyomavirus infection specifically targeting follicular keratinocytes in immunocompromised patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:629-632.

- van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- van der Meijden E, Horváth B, Nijland M, et al. Primary polyomavirus infection, not reactivation, as the cause of trichodysplasia spinulosa in immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1080-1084.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:726-733.

- Kazem S, van der Meijden E, Feltkamp MC. The trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus: virological background and clinical implications. APMIS. 2013;121:770-782.

- van Boheemen S, Jones T, Muhlemann B, et al. Cidofovir gel as treatment of follicular spicules in multiple myeloma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:82-84.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Barton M, Lockhart S, Sidbury R, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a 7-year-old boy managed using physical extraction of keratin spicules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:E74-E76.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and congestive heart failure presented with a disfiguring eruption comprised of asymptomatic papules on the face that appeared 12 months post–heart transplantation. Immunosuppressive medications included mycophenolic acid and tacrolimus ointment (FK506). The pinpoint papules spread from the central face to the ears, arms, and legs. Physical examination revealed multiple 0.5- to 1-mm flesh-colored papules over the glabella, nose, nasolabial folds, philtrum, chin, ears, arms, and legs sparing the trunk. The initial appearance of the facial rash resembled the surface of a nutmeg grater with central white spiny excrescences overlying fine papules (spinulosism)(Figure 1). In addition, eyebrow alopecia was present.

A 3-mm punch biopsy of a papule with a central spine was performed on the left thigh. Microscopic examination revealed marked dilatation of anagen hair follicles with a proliferation of haphazard inner root sheath cells replacing the follicular lumen. Hair shafts were absent, and plugged infundibula were observed (Figure 2). The inner root sheath keratinocytes were enlarged and dystrophic with deeply eosinophilic trichohyalin granules (Figure 3). The epidermis, outer root sheath epithelium, and eccrine structures were unremarkable.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed the presence of intranuclear viral inclusions within affected inner root sheath keratinocytes composed of nonenveloped icosahedral viral particles measuring 33 to 38 nm in diameter (Figure 4). These findings morphologically were consistent with a polyomavirus. No intracytoplasmic or extracellular viral particles were identified. The clinical history, physical examination, histopathology, and electron microscopy features strongly supported the diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) despite insufficient material being retrieved for polymerase chain reaction identification.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first described by Haycox et al1 in 1999. The authors suggested a viral etiology. Eleven years later, TS-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) was identified by van der Meijden et al.2 Follicular keratinocytes are the specific target for TSPyV.3 Evidence has been presented suggesting that TS is caused by a primary infection or reactivation of TSPyV in the setting of immunosuppression.4,5

Patients with TS present with papular eruptions that appear on the central face with spiny excrescences and various degrees of alopecia involving the eyebrows or eyelashes. Histopathologic features include distended hair follicles with expansion of inner root sheath cells, eosinophilic trichohyalin granules, and the absence of hair shafts. The viral protein can be verified through immunohistochemistry TSPyV VP1 staining that demonstrates co-localization with trichohyalin. Viral particles also can be visualized as 35- to 38-nm intranuclear particles with an organized crystalloid morphology on TEM.6,7 The negative polymerase chain reaction in our patient could be the result of suboptimal template DNA concentration extracted from the limited amount of tissue remaining in the block after hematoxylin and eosin staining.

The clinical differential diagnosis of central facial spinulosism includes the follicular spicules of multiple myeloma (FSMM). In fact, FSMM and TS can only be differentiated after obtaining a blood profile and bone marrow biopsy that excludes the diagnosis of FSMM. A history of immunosuppression typically suggests TS. Histopathology often is equivocal in FSMM8; however, TEM reveals viral particles (TSPyV) in TS. Transmission electron microscopy in FSMM demonstrates fibrillary structures arranged in a paracrystalline configuration with unknown significance instead of viral particles. Despite the absence of viral particles on TEM, a low mean copy number of Merkel cell polyomavirus was isolated from a patient with FSMM who responded dramatically to treatment with topical cidofovir gel 1%.8 In addition to treating the underlying multiple myeloma in FSMM, topical cidofovir gel 1% also may have a role in treatment of these patients, suggesting a possible viral rather than simply paraneoplastic etiology of FSMM. Therefore, polyomavirus infection should be considered in the initial workup of any patient with fine facial follicular spicules.

The most effective management of TS in transplant recipients is to reduce immunosuppression to the lowest level possible without jeopardizing the transplanted organ.9 In our case, reduction of immunosuppressive drugs was not possible. In fact, immunosuppression in our patient was increased following evidence of early rejection of the heart transplant. Although manual extraction of the keratin spicules resulted in considerable improvement in a similar facial eruption in a patient with pediatric pre–B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia developing TS,10 it is impossible to apply this approach to patients such as ours who have thousands of tiny lesions. Fortunately, custom-compounded cidofovir gel 1% applied twice daily to the patient’s face and ears for 4 weeks led to near-complete clearance at follow-up (Figure 5). Due to the high cost of the medication (approaching $700 for one tube), our patient applied this medication to the face only several times weekly with excellent improvement. Thus, it appears that it is possible to suppress this virus with topical medication alone.

Polyomavirus infection should be considered in patients presenting with fine follicular spiny papules, especially those who are immunosuppressed. The possibility of coexisting multiple myeloma should be excluded.

Acknowledgment—We sincerely thank Glenn A. Hoskins (Jackson, Mississippi), the electron microscopy technologist, for the detection of viral particles and the electron microscope photographs.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and congestive heart failure presented with a disfiguring eruption comprised of asymptomatic papules on the face that appeared 12 months post–heart transplantation. Immunosuppressive medications included mycophenolic acid and tacrolimus ointment (FK506). The pinpoint papules spread from the central face to the ears, arms, and legs. Physical examination revealed multiple 0.5- to 1-mm flesh-colored papules over the glabella, nose, nasolabial folds, philtrum, chin, ears, arms, and legs sparing the trunk. The initial appearance of the facial rash resembled the surface of a nutmeg grater with central white spiny excrescences overlying fine papules (spinulosism)(Figure 1). In addition, eyebrow alopecia was present.

A 3-mm punch biopsy of a papule with a central spine was performed on the left thigh. Microscopic examination revealed marked dilatation of anagen hair follicles with a proliferation of haphazard inner root sheath cells replacing the follicular lumen. Hair shafts were absent, and plugged infundibula were observed (Figure 2). The inner root sheath keratinocytes were enlarged and dystrophic with deeply eosinophilic trichohyalin granules (Figure 3). The epidermis, outer root sheath epithelium, and eccrine structures were unremarkable.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed the presence of intranuclear viral inclusions within affected inner root sheath keratinocytes composed of nonenveloped icosahedral viral particles measuring 33 to 38 nm in diameter (Figure 4). These findings morphologically were consistent with a polyomavirus. No intracytoplasmic or extracellular viral particles were identified. The clinical history, physical examination, histopathology, and electron microscopy features strongly supported the diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) despite insufficient material being retrieved for polymerase chain reaction identification.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first described by Haycox et al1 in 1999. The authors suggested a viral etiology. Eleven years later, TS-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) was identified by van der Meijden et al.2 Follicular keratinocytes are the specific target for TSPyV.3 Evidence has been presented suggesting that TS is caused by a primary infection or reactivation of TSPyV in the setting of immunosuppression.4,5

Patients with TS present with papular eruptions that appear on the central face with spiny excrescences and various degrees of alopecia involving the eyebrows or eyelashes. Histopathologic features include distended hair follicles with expansion of inner root sheath cells, eosinophilic trichohyalin granules, and the absence of hair shafts. The viral protein can be verified through immunohistochemistry TSPyV VP1 staining that demonstrates co-localization with trichohyalin. Viral particles also can be visualized as 35- to 38-nm intranuclear particles with an organized crystalloid morphology on TEM.6,7 The negative polymerase chain reaction in our patient could be the result of suboptimal template DNA concentration extracted from the limited amount of tissue remaining in the block after hematoxylin and eosin staining.

The clinical differential diagnosis of central facial spinulosism includes the follicular spicules of multiple myeloma (FSMM). In fact, FSMM and TS can only be differentiated after obtaining a blood profile and bone marrow biopsy that excludes the diagnosis of FSMM. A history of immunosuppression typically suggests TS. Histopathology often is equivocal in FSMM8; however, TEM reveals viral particles (TSPyV) in TS. Transmission electron microscopy in FSMM demonstrates fibrillary structures arranged in a paracrystalline configuration with unknown significance instead of viral particles. Despite the absence of viral particles on TEM, a low mean copy number of Merkel cell polyomavirus was isolated from a patient with FSMM who responded dramatically to treatment with topical cidofovir gel 1%.8 In addition to treating the underlying multiple myeloma in FSMM, topical cidofovir gel 1% also may have a role in treatment of these patients, suggesting a possible viral rather than simply paraneoplastic etiology of FSMM. Therefore, polyomavirus infection should be considered in the initial workup of any patient with fine facial follicular spicules.

The most effective management of TS in transplant recipients is to reduce immunosuppression to the lowest level possible without jeopardizing the transplanted organ.9 In our case, reduction of immunosuppressive drugs was not possible. In fact, immunosuppression in our patient was increased following evidence of early rejection of the heart transplant. Although manual extraction of the keratin spicules resulted in considerable improvement in a similar facial eruption in a patient with pediatric pre–B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia developing TS,10 it is impossible to apply this approach to patients such as ours who have thousands of tiny lesions. Fortunately, custom-compounded cidofovir gel 1% applied twice daily to the patient’s face and ears for 4 weeks led to near-complete clearance at follow-up (Figure 5). Due to the high cost of the medication (approaching $700 for one tube), our patient applied this medication to the face only several times weekly with excellent improvement. Thus, it appears that it is possible to suppress this virus with topical medication alone.

Polyomavirus infection should be considered in patients presenting with fine follicular spiny papules, especially those who are immunosuppressed. The possibility of coexisting multiple myeloma should be excluded.

Acknowledgment—We sincerely thank Glenn A. Hoskins (Jackson, Mississippi), the electron microscopy technologist, for the detection of viral particles and the electron microscope photographs.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromized patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Rouanet J, Aubin F, Gaboriaud P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a polyomavirus infection specifically targeting follicular keratinocytes in immunocompromised patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:629-632.

- van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- van der Meijden E, Horváth B, Nijland M, et al. Primary polyomavirus infection, not reactivation, as the cause of trichodysplasia spinulosa in immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1080-1084.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:726-733.

- Kazem S, van der Meijden E, Feltkamp MC. The trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus: virological background and clinical implications. APMIS. 2013;121:770-782.

- van Boheemen S, Jones T, Muhlemann B, et al. Cidofovir gel as treatment of follicular spicules in multiple myeloma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:82-84.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Barton M, Lockhart S, Sidbury R, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a 7-year-old boy managed using physical extraction of keratin spicules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:E74-E76.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromized patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Rouanet J, Aubin F, Gaboriaud P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a polyomavirus infection specifically targeting follicular keratinocytes in immunocompromised patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:629-632.

- van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- van der Meijden E, Horváth B, Nijland M, et al. Primary polyomavirus infection, not reactivation, as the cause of trichodysplasia spinulosa in immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1080-1084.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:726-733.

- Kazem S, van der Meijden E, Feltkamp MC. The trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus: virological background and clinical implications. APMIS. 2013;121:770-782.

- van Boheemen S, Jones T, Muhlemann B, et al. Cidofovir gel as treatment of follicular spicules in multiple myeloma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:82-84.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Barton M, Lockhart S, Sidbury R, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a 7-year-old boy managed using physical extraction of keratin spicules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:E74-E76.

Practice Points

- Trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) is a rare skin disease caused by primary TS-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) infecting follicular keratinocytes in immunocompromised patients.

- Trichodysplasia spinulosa typically presents with papular eruptions that appear on the central face with spiny excrescences and various degrees of alopecia involving the eyebrows or eyelashes.

- The viral protein can be verified through immunohistochemistry TSPyV major capsid protein VP1 staining or can be visualized on transmission electron microscopy.

- Follicular spicules of multiple myeloma should be ruled out before initiating treatment with cidofovir gel 1% for TS.

Authors’ response

My co-authors and I appreciate the excellent comments regarding our Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain,” and would like to provide some additional detail.

After our patient’s 27-day hospital stay, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center for continued inpatient physical therapy for 14 days due to weakness and deconditioning. Following his discharge from the rehabilitation center, the patient was still confined to a wheelchair. He was prescribed an oral prednisone taper (as mentioned in our article) and celecoxib 200 mg bid and referred for outpatient physical therapy. At a follow-up appointment with the rheumatologist, he received adalimumab 80 mg followed by 40 mg every other week, which led to improvement in his range of motion and pain. Two months after outpatient physical therapy, the patient was lost to follow-up.

We agree with Dr. Hahn et al that many of these patients with chlamydia-associated ReA become “long-haulers.” In medicine—especially when rare diseases are considered—we must often make decisions without perfect science. The studies referenced by Dr. Hahn et al suggest that combinations of doxycycline and rifampin or azithromycin and rifampin may treat not only chlamydial infection, but ReA and associated cutaneous disease, as well.1,2 While these studies are small in size, larger studies may never be funded. We agree that combination therapy should be considered in this population of patients.

Hannah R. Badon, MD

Ross L. Pearlman, MD

Robert T. Brodell, MD

Jackson, MS

1. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

2. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

My co-authors and I appreciate the excellent comments regarding our Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain,” and would like to provide some additional detail.

After our patient’s 27-day hospital stay, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center for continued inpatient physical therapy for 14 days due to weakness and deconditioning. Following his discharge from the rehabilitation center, the patient was still confined to a wheelchair. He was prescribed an oral prednisone taper (as mentioned in our article) and celecoxib 200 mg bid and referred for outpatient physical therapy. At a follow-up appointment with the rheumatologist, he received adalimumab 80 mg followed by 40 mg every other week, which led to improvement in his range of motion and pain. Two months after outpatient physical therapy, the patient was lost to follow-up.

We agree with Dr. Hahn et al that many of these patients with chlamydia-associated ReA become “long-haulers.” In medicine—especially when rare diseases are considered—we must often make decisions without perfect science. The studies referenced by Dr. Hahn et al suggest that combinations of doxycycline and rifampin or azithromycin and rifampin may treat not only chlamydial infection, but ReA and associated cutaneous disease, as well.1,2 While these studies are small in size, larger studies may never be funded. We agree that combination therapy should be considered in this population of patients.

Hannah R. Badon, MD

Ross L. Pearlman, MD

Robert T. Brodell, MD

Jackson, MS

My co-authors and I appreciate the excellent comments regarding our Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain,” and would like to provide some additional detail.

After our patient’s 27-day hospital stay, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center for continued inpatient physical therapy for 14 days due to weakness and deconditioning. Following his discharge from the rehabilitation center, the patient was still confined to a wheelchair. He was prescribed an oral prednisone taper (as mentioned in our article) and celecoxib 200 mg bid and referred for outpatient physical therapy. At a follow-up appointment with the rheumatologist, he received adalimumab 80 mg followed by 40 mg every other week, which led to improvement in his range of motion and pain. Two months after outpatient physical therapy, the patient was lost to follow-up.

We agree with Dr. Hahn et al that many of these patients with chlamydia-associated ReA become “long-haulers.” In medicine—especially when rare diseases are considered—we must often make decisions without perfect science. The studies referenced by Dr. Hahn et al suggest that combinations of doxycycline and rifampin or azithromycin and rifampin may treat not only chlamydial infection, but ReA and associated cutaneous disease, as well.1,2 While these studies are small in size, larger studies may never be funded. We agree that combination therapy should be considered in this population of patients.

Hannah R. Badon, MD

Ross L. Pearlman, MD

Robert T. Brodell, MD

Jackson, MS

1. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

2. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

1. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

2. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

Erythematous ear with drainage

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

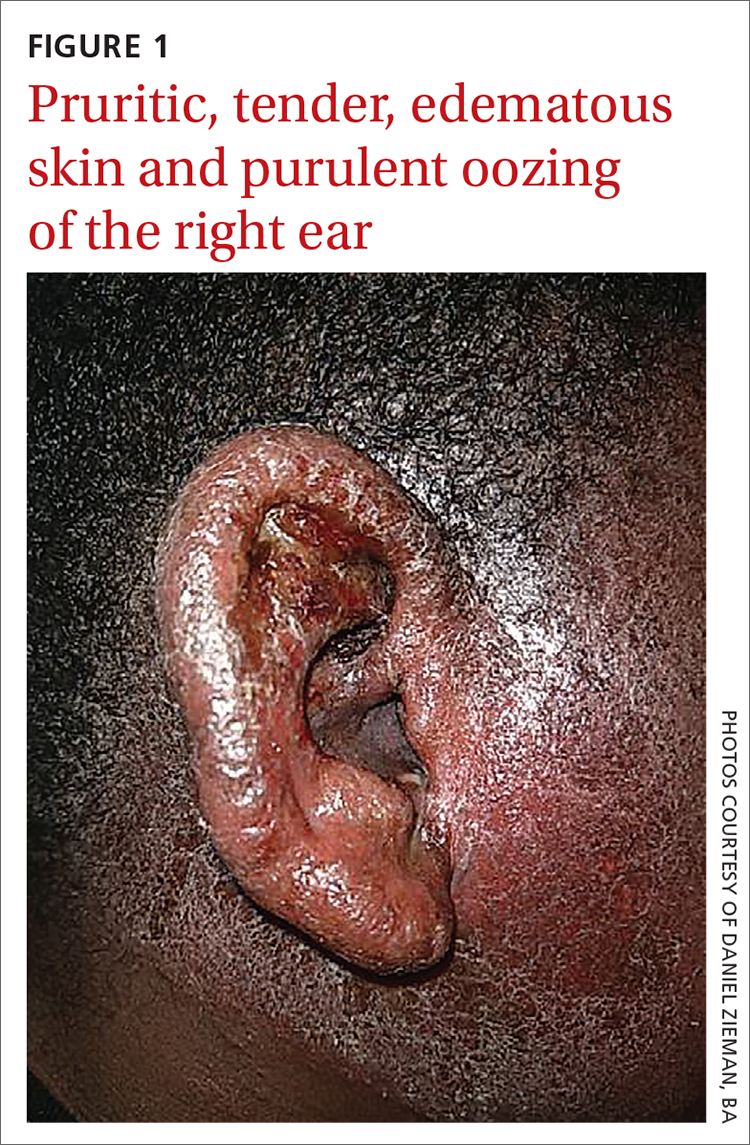

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

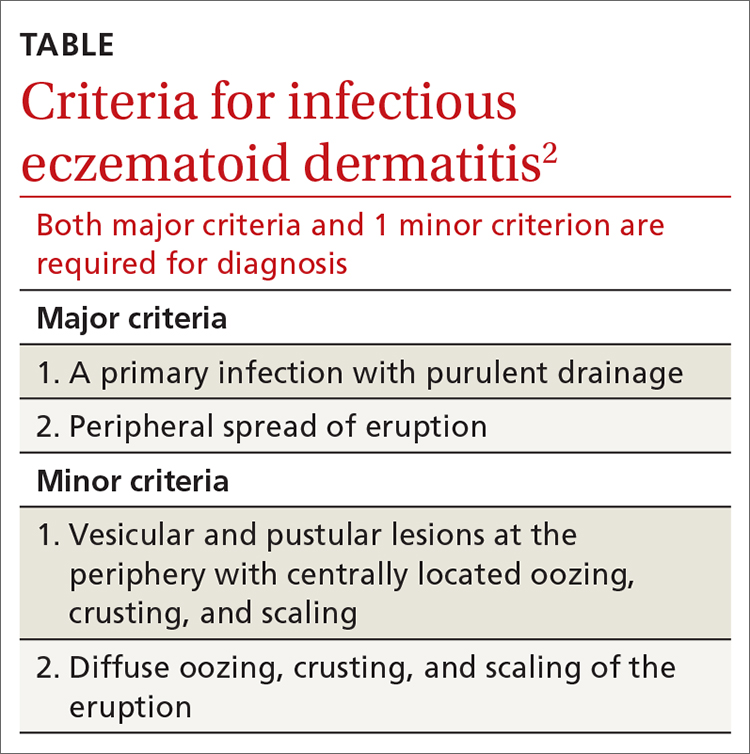

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

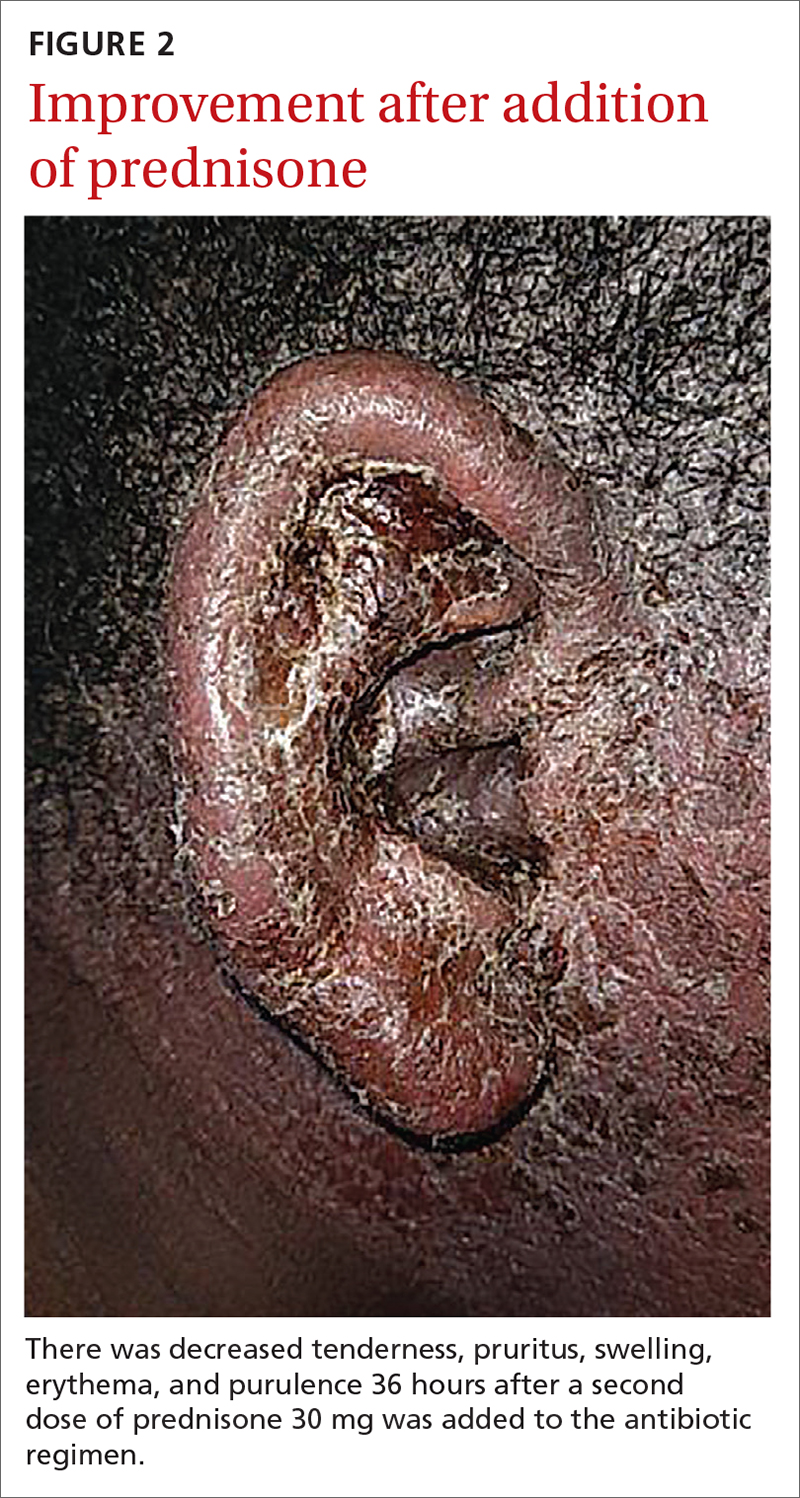

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

Foot rash and joint pain

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-month history of joint pain, swelling, and difficulty walking that began with swelling of his right knee (FIGURE 1A). The patient said that over the course of several weeks, the swelling and joint pain spread to his left knee, followed by bilateral elbows and ankles. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin produced only modest improvement.

Two weeks prior to presentation, the patient also experienced widespread pruritus and conjunctivitis. His past medical history was significant for a sexual encounter that resulted in urinary tract infection (UTI)–like symptoms approximately 1 month prior to the onset of his joint symptoms. He did not seek care for the UTI-like symptoms.

In the ED, the patient was febrile (102.1 °F) and tachycardic. Skin examination revealed erythematous papules, intact vesicles, and pustules with background hyperkeratosis and desquamation on his right foot (FIGURE 1B). The patient had spotty erythema on his palate and a 4-mm superficial erosion on the right penile shaft. Swelling and tenderness were noted over the elbows, knees, hands, and ankles. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted.

An arthrocentesis was performed on the right knee that demonstrated no organisms on Gram stain and a normal joint fluid cell count. A complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and urinalysis were ordered. A punch biopsy was performed on a scaly patch on the right elbow.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The patient’s history, clinical findings, and lab results, including a positive Chlamydia trachomatis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test from a urethral swab, pointed to a diagnosis of keratoderma blenorrhagicum in association with reactive arthritis (following infection with C trachomatis).

Relevant diagnostic findings included an elevated CRP of 26.5 mg/L (normal range, < 10 mg/L), an elevated ESR of 116 mm/h (normal range, < 15 mm/h) and as noted, a positive C trachomatis PCR test. The patient’s white blood cell count was 9.7/μL (normal range, 4.5-11 μL) and the rest of the CBC was within normal limits. Urinalysis was positive for leukocytes and rare bacteria. A treponemal antibody test was negative.

Additionally, the punch biopsy from the right elbow revealed acanthosis, intercellular spongiosis, and subcorneal pustules consistent with localized pustular psoriasis or keratoderma blenorrhagicum. After the diagnosis was made, human leukocyte antigen B27 allele (HLA-B27) testing was conducted and was positive.

A predisposition exacerbates the infection

Reactive arthritis, a type of spondyloarthropathy, features a triad of conjunctivitis, urethritis, and arthritis that follows either gastrointestinal or urogenital infection.1 Reactive arthritis occurs with a male predominance of 3:1, and the worldwide prevalence is 1 in 3000.1 Causative bacteria include C trachomatis, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile, and C pneumoniae.2 Patients with the HLA-B27 allele are 50 times more likely to develop reactive arthritis following infection with the aforementioned bacteria.1

Findings consistent with a diagnosis of reactive arthritis include a recent history of gastrointestinal or urogenital illness, joint pain, conjunctivitis, oral lesions, cutaneous changes, and genital lesions.3 Diagnostic tests should include arthrocentesis with cultures or PCR and cell count, ESR, CRP, CBC, and urinalysis. HLA-B27 can be used to support the diagnosis but is not routinely recommended.2

Pustules and psoriasiform scaling characterize this diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the signs and symptoms seen in this patient include disseminated gonococcal arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and secondary syphilis.

Gonococcal arthritis manifests with painful, sterile joints as well as pustules on the palms and soles, but not with the psoriasiform scaling and desquamation that was seen in this case. A culture or PCR from urethral discharge or pustules on the palms and soles could be used to confirm this diagnosis.3

Continue to: Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis

Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis and the psoriasiform rashing of reactive arthritis (keratoderma blenorrhagicum) show similar histopathology; however, patients with psoriatic arthritis generally exhibit fewer constitutional symptoms.4

Rheumatoid arthritis also manifests with joint pain and swelling, especially in the hands, wrists, and knees. This diagnosis was unlikely in this patient, where small joints were largely uninvolved.4

Secondary syphilis also manifests with papular, scaly, erythematous lesions on the palms and soles along with pityriasis rosea–like rashing on the trunk. However, it rarely produces pustules or hyperkeratotic keratoderma.5 As noted earlier, a treponemal antibody test in this patient was negative.

Drug therapy is the best option

First-line therapy for reactive arthritis consists of NSAIDs. If the patient exhibits an inadequate response after a 2-week trial, intra-articular or systemic glucocorticoids may be considered.3 If the patient fails to respond to the steroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be considered. Reactive arthritis is considered chronic if the disease lasts longer than 6 months, at which point, DMARDs or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors may be utilized.3 For cutaneous manifestations, such as keratoderma blenorrhagicum, topical glucocorticoids twice daily may be used along with keratolytic agents.

Our patient received 2 doses of azithromycin (500 mg IV) and 1 dose of ceftriaxone (2 g IV) to treat his infection while in the ED. Over the course of his hospital stay, he received ceftriaxone (1 g IV daily) for 6 days and naproxen (500 mg tid po) which was tapered. Additionally, he received a week of methylprednisolone (60 mg IM daily) before tapering to oral prednisone. His taper consisted of 40 mg po for 1 week and was decreased by 10 mg each week. Augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream and urea 20% cream were prescribed for twice-daily application for the hyperkeratotic scale on both of his feet.

1. Hayes KM, Hayes RJP, Turk MA, et al. Evolving patterns of reactive arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2083-2088. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04522-4

2. Duba AS, Mathew SD. The seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Prim Care. 2018;45:271-287. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.005

3. Yu DT, van Tubergen A. Reactive arthritis. In: Joachim S, Romain PL, eds. UpToDate. Updated April 28, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis?search=reactive%20arthritis&topicRef=5571&source=see_link#H9

4. Barth WF, Segal K. Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome). Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:499-503, 507.

5. Coleman E, Fiahlo A, Brateanu A. Secondary syphilis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:510-511. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84a.16089

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-month history of joint pain, swelling, and difficulty walking that began with swelling of his right knee (FIGURE 1A). The patient said that over the course of several weeks, the swelling and joint pain spread to his left knee, followed by bilateral elbows and ankles. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin produced only modest improvement.

Two weeks prior to presentation, the patient also experienced widespread pruritus and conjunctivitis. His past medical history was significant for a sexual encounter that resulted in urinary tract infection (UTI)–like symptoms approximately 1 month prior to the onset of his joint symptoms. He did not seek care for the UTI-like symptoms.

In the ED, the patient was febrile (102.1 °F) and tachycardic. Skin examination revealed erythematous papules, intact vesicles, and pustules with background hyperkeratosis and desquamation on his right foot (FIGURE 1B). The patient had spotty erythema on his palate and a 4-mm superficial erosion on the right penile shaft. Swelling and tenderness were noted over the elbows, knees, hands, and ankles. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted.