User login

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

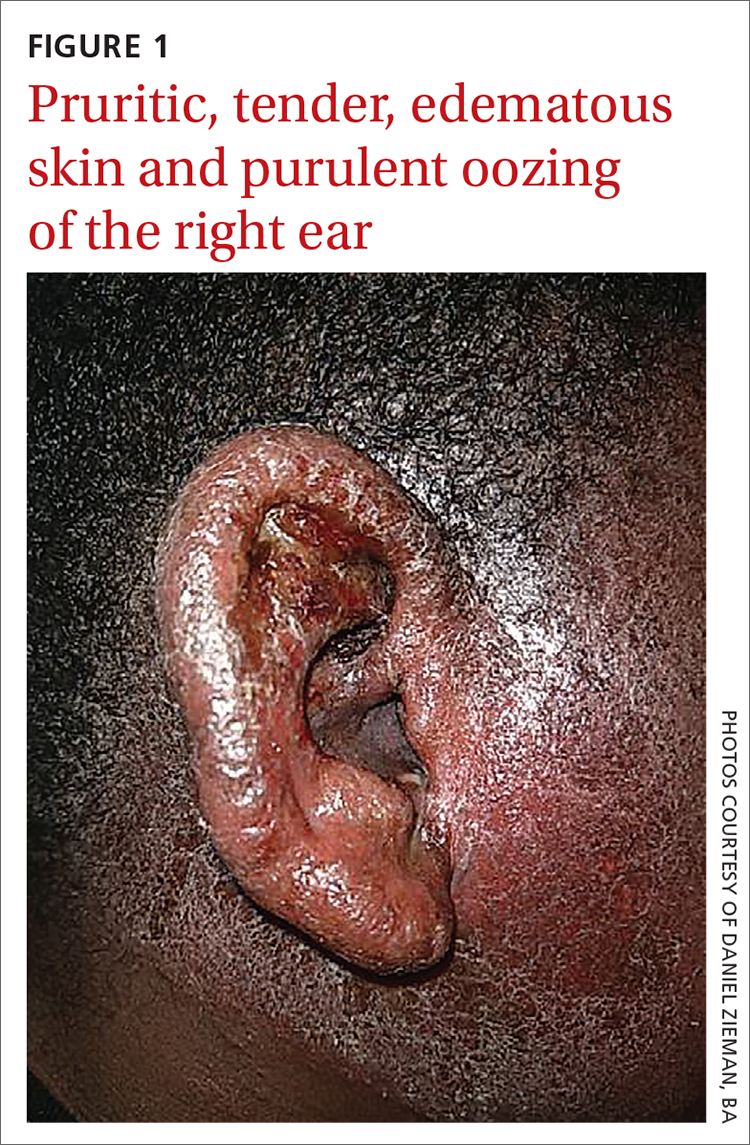

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

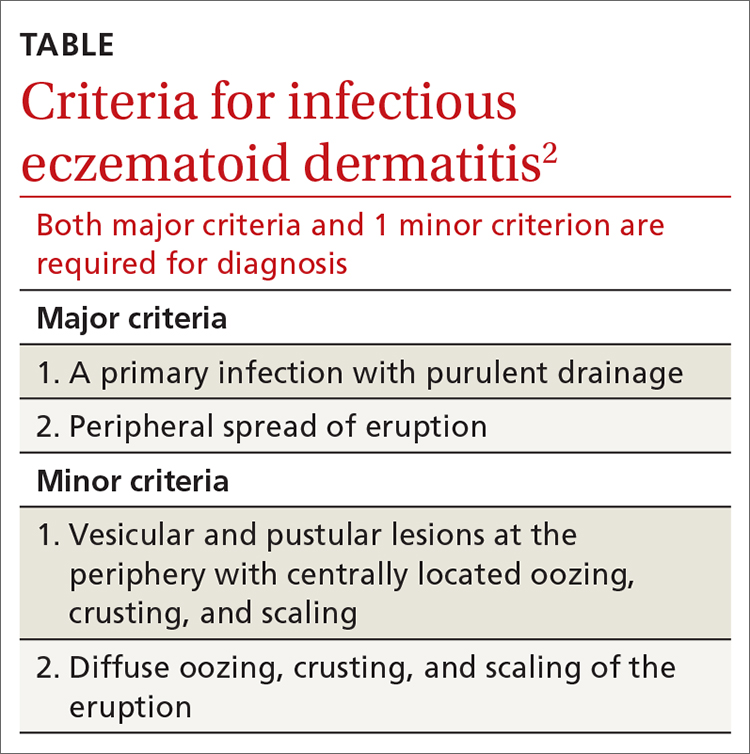

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

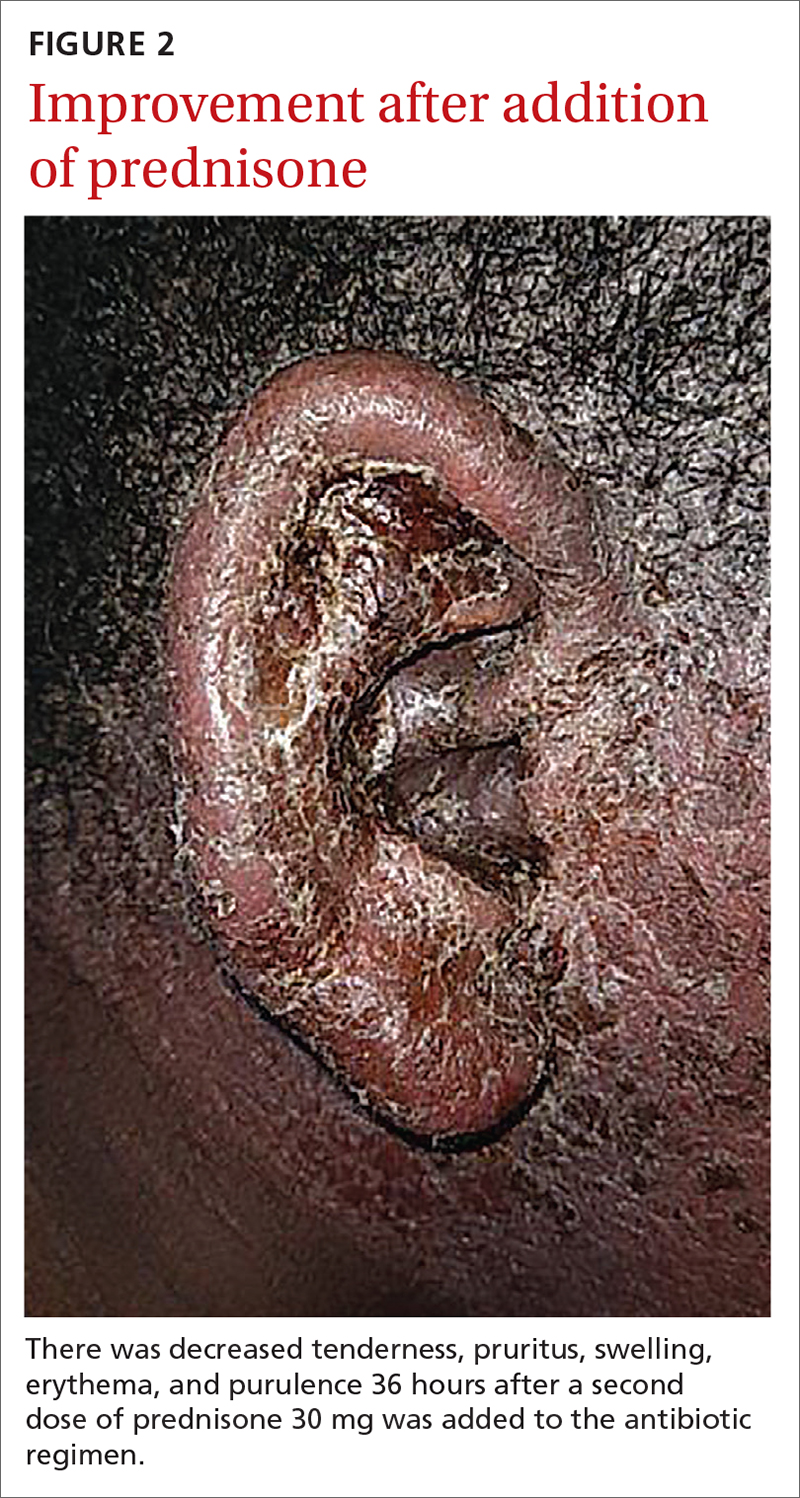

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021