User login

Idiopathic Livedo Racemosa Presenting With Splenomegaly and Diffuse Lymphadenopathy

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

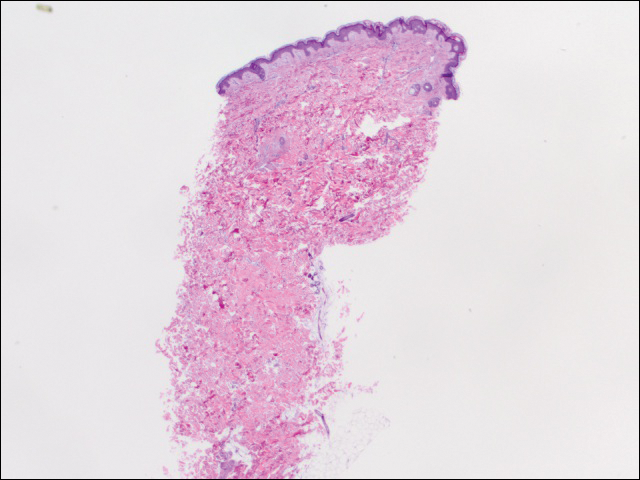

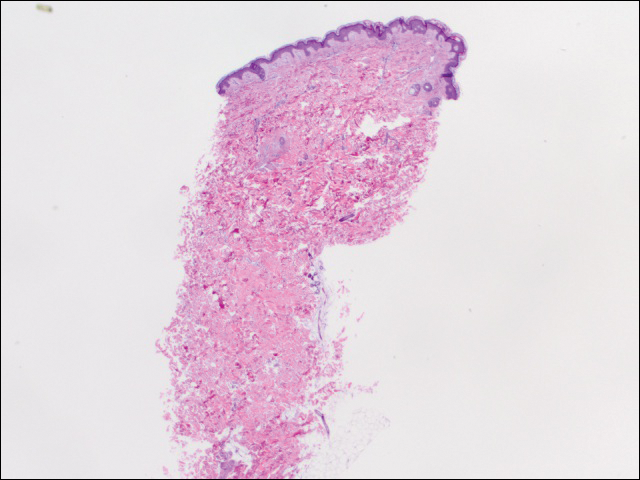

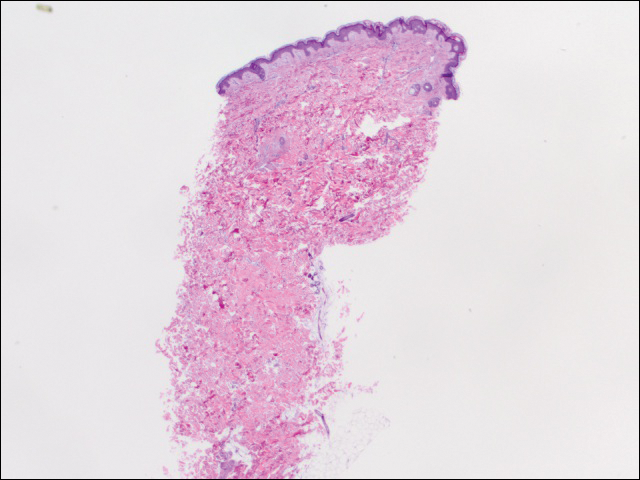

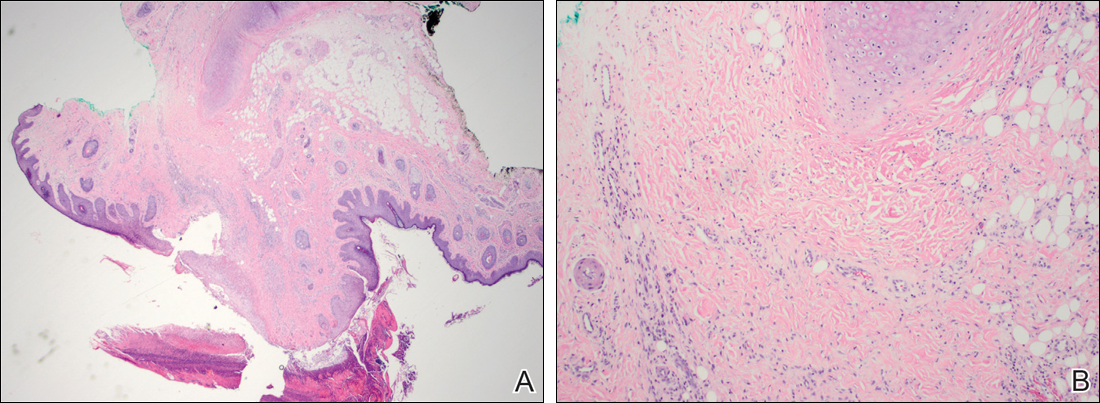

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

Practice Points

- The classic physical diagnostic finding of Sneddon syndrome (SS) is livedo racemosa.

- Early identification and treatment of SS can prevent serious morbidity due to stroke, myocardial infarction, and other thrombotic events.

- Preventive care in SS should include antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulants and smoking cessation along with avoidance of birth control pills.

Necrotic Lesion of the Ear

The Diagnosis: Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis

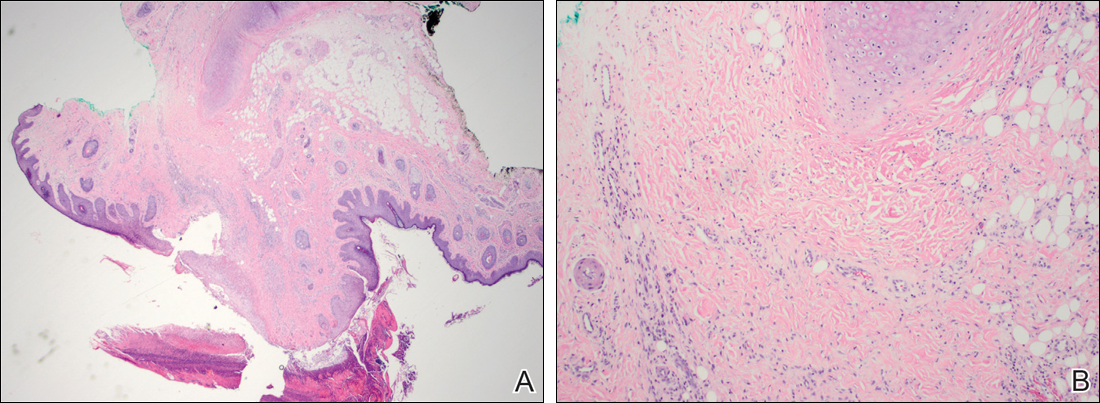

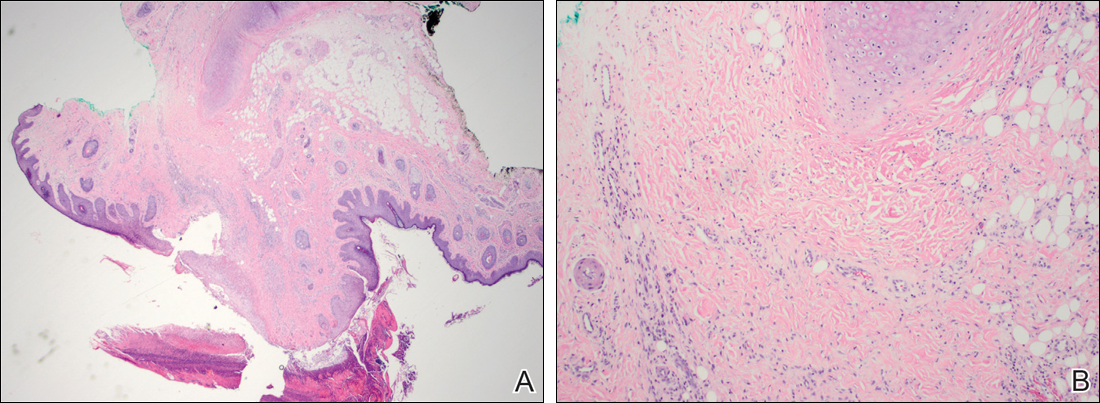

Histopathologic examination revealed focal epidermal erosion and ulceration directly overlying the hyaline cartilage with degenerative changes (Figure). The dermis was relatively noninflamed with fibroplasia of the vasculature. The blood vessels indirectly beneath the ulceration were found to be unremarkable with no indications of fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, or the presence of thrombi. The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which point she reported that she slept on the right side. The excisional biopsy site healed well without recurrence of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis (CNH).

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as clavus helicis, is a benign, usually solitary, painful lesion. Historically, it was first described in 1915 by Winkler1 and in the 1960s the most common documented cases were attributed to the headpieces of telephone operators and nuns.2 In the early 2000s, cell phones were determined to be a growing cause.3 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis is most commonly found on the helix with the antihelix being affected less often.4 The condition is more common in men, with a male to female ratio being reported as high as 10:1. Possible causes of this disorder stem from damage to cartilage associated with pressure, sun exposure, cold temperatures, and microvascular disease. Additionally, some researchers have hypothesized that the cartilaginous damage resulting from solar elastosis and minor trauma leaves a susceptibility to CNH. This disorder usually presents as a small, exquisitely tender nodule that may ulcerate and crust.4 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, and weathering nodules, though CNH tends to be more painful.

The diagnosis of CNH often is clinical but may require a skin biopsy. Histopathology of CNH shows a benign inflammatory lesion with an acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis that may be ulcerated. A primarily lymphocytic infiltrate usually is observed with variable presence of histiocytes and neutrophils. Cartilaginous changes range from simple perichondral thickening to notable areas of degeneration with calcification and ossification.4

Although the diagnosis of CNH often is straightforward, the remarkable necrosis present in our case made for an interesting differential diagnosis. Pernio, cryoglobulinemia, and levamisole-induced vasculopathy were all considered. Pernio, caused by cold-induced vasoconstriction and hypoxemia, classically presents as erythematous lesions with a symmetrical distribution on acral sites.5 Cryoglobulinemia involves proteins that precipitate at cold temperatures causing damage via an occlusive vasculopathy or an immune complex-mediated vasculitis. The presence of cryoglobulinemia is strongly associated with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection.6 Ulcerated and purpuric lesions of cryoglobulinemia may become necrotic. Levamisole is a veterinary antihelminthic drug and common cocaine contaminant, often added to cocaine as a cutting agent. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy favors acral sites and often is noted on the ears as purpuric patches, sometimes with necrosis.7

Several therapies for CNH have been reported with variable effectiveness.8 First-line treatments are the use of pressure-relieving devices including a doughnut-shaped pillow during sleep and intralesional corticosteroids.9 Surgical treatments including cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, wedge resection with helical rim advancement flap, punch and graft technique, and CO2 laser have been tried.8 Photodynamic therapy and topical nitroglycerine also have shown to be of benefit.8,9

Our case of CNH is unique because of the remarkable degree of necrosis present on clinical examination. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis with such an impressive necrotic presentation is rare. We speculate that the patient's underlying hypercoagulable state may have contributed to the dramatic presentation. It is important to keep CNH in mind when evaluating any necrotic lesion on the ear.

- Winkler M. Knötcehnformige Erkrankung am helix. chondrodermatitis nodularis chronic helicis. Arch für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 1915;121:278-285.

- Barker L, Young AW, Sachs W. Chondrodermatitis of the ears: a differential study of nodules of the helix and antihelix. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:15-25.

- Elgart M. Cell phone chondrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:844-848.

- King JM, Plotner AN, Adams BB. Perniosis induced by a cold-therapy system. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1101-1102.

- Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, et al. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151.

- Hennings C, Miller J. Illicit drugs: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:135-142.

- Flynn V, Chisholm C, Grimwood R. Topical nitroglycerin: a promising treatment option for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:531-536.

- Gilaberte Y, Frias M, Pérez-Lorenz J. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1080-1082.

The Diagnosis: Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis

Histopathologic examination revealed focal epidermal erosion and ulceration directly overlying the hyaline cartilage with degenerative changes (Figure). The dermis was relatively noninflamed with fibroplasia of the vasculature. The blood vessels indirectly beneath the ulceration were found to be unremarkable with no indications of fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, or the presence of thrombi. The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which point she reported that she slept on the right side. The excisional biopsy site healed well without recurrence of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis (CNH).

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as clavus helicis, is a benign, usually solitary, painful lesion. Historically, it was first described in 1915 by Winkler1 and in the 1960s the most common documented cases were attributed to the headpieces of telephone operators and nuns.2 In the early 2000s, cell phones were determined to be a growing cause.3 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis is most commonly found on the helix with the antihelix being affected less often.4 The condition is more common in men, with a male to female ratio being reported as high as 10:1. Possible causes of this disorder stem from damage to cartilage associated with pressure, sun exposure, cold temperatures, and microvascular disease. Additionally, some researchers have hypothesized that the cartilaginous damage resulting from solar elastosis and minor trauma leaves a susceptibility to CNH. This disorder usually presents as a small, exquisitely tender nodule that may ulcerate and crust.4 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, and weathering nodules, though CNH tends to be more painful.

The diagnosis of CNH often is clinical but may require a skin biopsy. Histopathology of CNH shows a benign inflammatory lesion with an acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis that may be ulcerated. A primarily lymphocytic infiltrate usually is observed with variable presence of histiocytes and neutrophils. Cartilaginous changes range from simple perichondral thickening to notable areas of degeneration with calcification and ossification.4

Although the diagnosis of CNH often is straightforward, the remarkable necrosis present in our case made for an interesting differential diagnosis. Pernio, cryoglobulinemia, and levamisole-induced vasculopathy were all considered. Pernio, caused by cold-induced vasoconstriction and hypoxemia, classically presents as erythematous lesions with a symmetrical distribution on acral sites.5 Cryoglobulinemia involves proteins that precipitate at cold temperatures causing damage via an occlusive vasculopathy or an immune complex-mediated vasculitis. The presence of cryoglobulinemia is strongly associated with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection.6 Ulcerated and purpuric lesions of cryoglobulinemia may become necrotic. Levamisole is a veterinary antihelminthic drug and common cocaine contaminant, often added to cocaine as a cutting agent. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy favors acral sites and often is noted on the ears as purpuric patches, sometimes with necrosis.7

Several therapies for CNH have been reported with variable effectiveness.8 First-line treatments are the use of pressure-relieving devices including a doughnut-shaped pillow during sleep and intralesional corticosteroids.9 Surgical treatments including cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, wedge resection with helical rim advancement flap, punch and graft technique, and CO2 laser have been tried.8 Photodynamic therapy and topical nitroglycerine also have shown to be of benefit.8,9

Our case of CNH is unique because of the remarkable degree of necrosis present on clinical examination. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis with such an impressive necrotic presentation is rare. We speculate that the patient's underlying hypercoagulable state may have contributed to the dramatic presentation. It is important to keep CNH in mind when evaluating any necrotic lesion on the ear.

The Diagnosis: Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis

Histopathologic examination revealed focal epidermal erosion and ulceration directly overlying the hyaline cartilage with degenerative changes (Figure). The dermis was relatively noninflamed with fibroplasia of the vasculature. The blood vessels indirectly beneath the ulceration were found to be unremarkable with no indications of fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, or the presence of thrombi. The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which point she reported that she slept on the right side. The excisional biopsy site healed well without recurrence of chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis (CNH).

Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, also known as clavus helicis, is a benign, usually solitary, painful lesion. Historically, it was first described in 1915 by Winkler1 and in the 1960s the most common documented cases were attributed to the headpieces of telephone operators and nuns.2 In the early 2000s, cell phones were determined to be a growing cause.3 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis is most commonly found on the helix with the antihelix being affected less often.4 The condition is more common in men, with a male to female ratio being reported as high as 10:1. Possible causes of this disorder stem from damage to cartilage associated with pressure, sun exposure, cold temperatures, and microvascular disease. Additionally, some researchers have hypothesized that the cartilaginous damage resulting from solar elastosis and minor trauma leaves a susceptibility to CNH. This disorder usually presents as a small, exquisitely tender nodule that may ulcerate and crust.4 Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, and weathering nodules, though CNH tends to be more painful.

The diagnosis of CNH often is clinical but may require a skin biopsy. Histopathology of CNH shows a benign inflammatory lesion with an acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis that may be ulcerated. A primarily lymphocytic infiltrate usually is observed with variable presence of histiocytes and neutrophils. Cartilaginous changes range from simple perichondral thickening to notable areas of degeneration with calcification and ossification.4

Although the diagnosis of CNH often is straightforward, the remarkable necrosis present in our case made for an interesting differential diagnosis. Pernio, cryoglobulinemia, and levamisole-induced vasculopathy were all considered. Pernio, caused by cold-induced vasoconstriction and hypoxemia, classically presents as erythematous lesions with a symmetrical distribution on acral sites.5 Cryoglobulinemia involves proteins that precipitate at cold temperatures causing damage via an occlusive vasculopathy or an immune complex-mediated vasculitis. The presence of cryoglobulinemia is strongly associated with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection.6 Ulcerated and purpuric lesions of cryoglobulinemia may become necrotic. Levamisole is a veterinary antihelminthic drug and common cocaine contaminant, often added to cocaine as a cutting agent. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy favors acral sites and often is noted on the ears as purpuric patches, sometimes with necrosis.7

Several therapies for CNH have been reported with variable effectiveness.8 First-line treatments are the use of pressure-relieving devices including a doughnut-shaped pillow during sleep and intralesional corticosteroids.9 Surgical treatments including cryotherapy, simple excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, wedge resection with helical rim advancement flap, punch and graft technique, and CO2 laser have been tried.8 Photodynamic therapy and topical nitroglycerine also have shown to be of benefit.8,9

Our case of CNH is unique because of the remarkable degree of necrosis present on clinical examination. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis with such an impressive necrotic presentation is rare. We speculate that the patient's underlying hypercoagulable state may have contributed to the dramatic presentation. It is important to keep CNH in mind when evaluating any necrotic lesion on the ear.

- Winkler M. Knötcehnformige Erkrankung am helix. chondrodermatitis nodularis chronic helicis. Arch für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 1915;121:278-285.

- Barker L, Young AW, Sachs W. Chondrodermatitis of the ears: a differential study of nodules of the helix and antihelix. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:15-25.

- Elgart M. Cell phone chondrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:844-848.

- King JM, Plotner AN, Adams BB. Perniosis induced by a cold-therapy system. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1101-1102.

- Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, et al. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151.

- Hennings C, Miller J. Illicit drugs: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:135-142.

- Flynn V, Chisholm C, Grimwood R. Topical nitroglycerin: a promising treatment option for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:531-536.

- Gilaberte Y, Frias M, Pérez-Lorenz J. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1080-1082.

- Winkler M. Knötcehnformige Erkrankung am helix. chondrodermatitis nodularis chronic helicis. Arch für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 1915;121:278-285.

- Barker L, Young AW, Sachs W. Chondrodermatitis of the ears: a differential study of nodules of the helix and antihelix. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:15-25.

- Elgart M. Cell phone chondrodermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Peltre B. Neural hyperplasia in chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:844-848.

- King JM, Plotner AN, Adams BB. Perniosis induced by a cold-therapy system. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1101-1102.

- Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, et al. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151.

- Hennings C, Miller J. Illicit drugs: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:135-142.

- Flynn V, Chisholm C, Grimwood R. Topical nitroglycerin: a promising treatment option for chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:531-536.

- Gilaberte Y, Frias M, Pérez-Lorenz J. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1080-1082.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a painful necrotic lesion on the right ear of 1 month's duration. She denied trauma to the ear and had no other skin lesions elsewhere on the body. A course of doxycycline prior to presentation did not result in improvement. Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, deep vein thrombosis, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. She had been taking warfarin regularly for years. She denied using recreational drugs. On physical examination, the right ear demonstrated a 6-mm necrotic area with surrounding tender erythema. Examinations of the left ear, face, and legs were normal. An excisional biopsy was performed.