User login

There is now great interest in the Supreme Court’s handling of cases that involve a woman’s ability to have an abortion. Recent decisions, and those planned in the next few months will be the source of intense scrutiny. But the Court’s involvement in reproductive rights did not begin with abortion. In fact, the Supreme Court has a long history of controversial decisions dealing with reproductive rights.

Involuntary sterilization

A notable, even infamous, case was Buck v Bell (1927)—later discredited—in which the Court reviewed a state law that provided for the involuntary sterilization of the “feeble minded.”1 The 8-1 decision was that the state could choose to have such a law to protect the so-called genetic health of the state. The law was based on a theory of eugenics. The opinion by the highly respected Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes included the unfortunate conclusion, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”2 As mentioned, the law has since been thoroughly discredited. In 1942, the Court did come to a different result, holding in Skinner v Oklahoma that it was unconstitutional for a state to involuntarily sterilize “habitual criminals.”3

Contraception

Forty years after Buck, in Griswold v Connecticut, the Court reviewed a state law that prohibited the distribution of any drug or device used for contraception (even for married couples).4 In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the state law as violating a marital right of privacy. Beyond its specific holding, Griswold was important in several ways. First, a physician was raising the rights of patients (not specifically his own rights). This is notable because, ordinarily in court, litigants may argue their own rights, not the rights of others. This has been important in later reproductive rights cases because often it has been physicians raising and arguing the rights of patients.

A second interesting part of Griswold was the source of this constitutional right of privacy. The Constitution contains no express privacy provision. In Griswold, the Court found that the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 9th Amendments create the right to privacy in marital relations. Writing for the majority, Justice Douglas found that “emanations” from these amendments have “penumbras” that create a right of marital privacy.

Although Griswold was based on marital privacy, a few years later, in 1972, the Court essentially converted that right to one of reproductive privacy (“the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”) In Eisenstadt v Baird, the Court held that it was a violation of equal protection (the 14th Amendment) for a state to allow contraception to the married but deny it to an unmarried person.5

Continue to: Abortion...

Abortion

In 1971, the Court had heard arguments in 2 cases that raised issues regarding whether state laws prohibiting abortion were constitutional. The first oral argument in Roe v Wade is widely considered one of the worst oral arguments in modern history, and for several reasons the Court set the case for rehearing the following Term (October 1972). In January 1973, the Court decided Roe v Wade.6 The 7-2 decision was written by Justice Blackmun, who had at one point been the attorney for the Mayo Clinic and might be considered one of the first “health lawyers.” The Court held that the Constitution (perhaps in the 14th or 9th Amendment) includes a right of privacy that includes the right of a woman to choose to have, or not to have, an abortion. In implementing the right, the Court held that a state may impose only modest medical safeguards for the mother (eg, requiring that abortions be performed by a licensed physician). In the second trimester, to the point of viability, a state could impose only limitations on abortion that were reasonably directed to ensure the health of the mother. After a fetus was viable (could live outside the mother’s body), the state was free to regulate or prohibit abortions and protect the fetus. At the time, viability was approximately the beginning of the third trimester.6

The clear majority of the Court in Roe (7-2) may have suggested that there was not strong opposition to the decision. That, of course, was not the case. Legal and political conflict surrounding the case has been, and remains, intense. Since 1973, the Court has been called upon to decide many abortion cases, and each case seems to beget more controversy and still more cases.

Some of the legal objections to Roe and other abortion decisions are that the constitutional basis for the decision remains unclear—a specific right of privacy is not contained in the text of the Constitution. Several locations of a possible right of privacy have been mentioned by various justices, but “substantive due process” became the common constitutional basis for the right. Critics note that “substantive” due process (as opposed to procedural due process) is not mentioned in the Constitution, and it is short on clear guiding principles. Beyond those jurisprudential issues, of course, there were strong religious and philosophical objections to abortion. What followed Roe has been a long series of efforts to limit or discourage access to abortion, and the Supreme Court has had to decide a great many abortion cases (and a few contraception cases) over the last 50 years. Most years (except from 2008‒2013) the Court has heard, on average, at least one abortion case.

By way of examples, here are some of the issues related to abortion that the Court has decided:

- Payment and facilities. States and the federal government are not required to pay for abortions for women who cannot afford them or to provide facilities for abortion.7-10

- Informed consent. Some states’ special informed consent requirements for abortion were upheld, but complex consents that required the father’s participation were not.

- Ability to advertise. Prohibitions on advertisement of abortion services were struck down.

- Location. Requirements for hospital-only abortions (or similar regulations) were struck down.

- Anti-abortion protests. Several cases addressed guidelines involving demonstrations near abortion clinics.

Of particular importance was the case of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey—“Casey.”11 In 1992 that case reaffirmed the “essential” holding of Roe v Wade. A plurality in that case de-emphasized the trimester framework and applied an “undue burden” test on limitations on abortion. In the more recent cases argued before the Court, Casey is frequently referred to as specifically reaffirming, and therefore solidifying, Roe.

Consent for minors

There have been several cases since 1973 that involved contraceptives or abortions and “minors” (generally, adolescents aged <18 years, although there are some state-defined exceptions). These cases typically involve 2 issues: the right of minors to consent to treatment and the obligation of the physician to provide information to parents about treatment to their minor daughter. In 1977 the Court struck down a New York law that prohibited the distribution of contraceptives to minors.12 However, abortion issues involving minors have been more complicated. While the Court has struck down “2-parent” consent statutes,13 it has generally upheld 1-parent consent statutes, but only if those statutes contain a “judicial bypass” provision and an emergency medical provision.11,14,15 (This bypass allows a minor to “bypass” parental consent to abortion in some circumstances, and instead seek judicial authorization for an abortion.) Generally, the Court has upheld parental notification for abortions, with exceptions where it would be harmful to the minor who is seeking the abortion.16-19

Continue to: Who can perform an abortion...

Who can perform an abortion

Over the years there have also been several cases raising questions about the professionals who can perform abortions, their hospital privileges, and what facilities can perform abortions. Two of those cases in recent years have, for example, seen the Court strike down state statutes that required the physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at least in 1 nearby hospital.20,21 The basis for these decisions is that the admitting qualification is an “undue burden” because it serves almost no health purpose, while significantly limiting the number of professionals who can perform abortions.

Cases this Term

The current Term of the Court (officially the “October 2021 Term”) may be one of the most significant for reproductive rights in recent history. The Court accepted 6 abortion-related cases to hear. It dismissed 3 of those cases, which had become “moot” because the Biden administration changed the rules that had been legally challenged.22-24 It has heard arguments in the 3 (technically 4) remaining cases, in which decisions will be announced over the next several months.

The first of these cases (involving the Texas Heartbeat Act) raises very important, but vexing, procedural issues about a Texas abortion law. The second (Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson) is a direct challenge to Roe v Wade. The third case (Cameron v EMW Women’s Surgical Center) involves the narrow question of whether a state attorney general can intervene in a case to uphold a state abortion law when another state official refuses to defend the law.25 It is worthwhile taking a look at the first 2 of these cases.

Texas Heartbeat Act

In the first case (technically, it is 2 cases, as we will see), the Texas legislature adopted a law that prohibits abortions after there is a discernable heartbeat (around 6 weeks of pregnancy). The law precludes state officials from enforcing the law. Instead, it allows almost any private citizen to seek monetary damages ($10,000 plus fees) from anyone who performs an abortion or “aids and abets” an abortion. (This is in some ways similar to “private attorney general” actions found in the False Claims Act, and in some civil rights and labor laws.) This statute is clearly inconsistent with Roe in that it prohibits abortions before the end of the second trimester. If it were a usual law—a Texas law being enforced by state officials—federal courts would issue injunctions to state officials against enforcing the law. The difficulty with the Texas law (and its very purpose) is that there are procedural limitations in federal law that make it very difficult to find a path for federal courts to review the Texas statute quickly. For example, would federal courts enjoin every private citizen of the state? There is a longstanding Constitutional doctrine that precludes federal courts from enjoining state courts.26 Therefore, it is difficult to challenge the law before someone performing or aiding an abortion has been ordered to pay the private citizen who is enforcing it. In the interim, which could be months or even years, health care providers face uncertainty about continuing to provide abortion services. Some providers would stop providing abortion services, reducing the availability of those services.

Two cases challenge this Texas procedure. In the first, Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, 27 abortion providers seek to find some way through the procedural thicket to allow an immediate challenge to the statute. It is important because this technique of exclusive private enforcement could be used in any number of ways by the state to chill important constitutional rights (beyond abortion—to speech, to bear arms). In the second case involving the Texas law, U.S. v Texas, the federal government seeks to intervene in the case, which is another unusual procedure.28 The Court found these questions so important and difficult that it allowed 3 hours of argument (and 4 sets of lawyers). It seems likely that the Court will find a mechanism for allowing some early federal court review of individual enforcement of state laws, while minimizing harm to the state-national federalism that is at the heart of the Constitution.

For the recent procedural decisions in the Texas cases, see the “Current Court Decisions” box below.

On December 10, 2021, the Court handed down two decisions in reproductive freedom (abortion) cases, both involving the Texas abortion law (which prohibits most abortions after a fetal heartbeat can be detected and allows only private individuals to enforce the law). The more significant of the two cases, Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson,1 was the request of abortion providers (and others) to allow them to challenge the constitutionality of the Texas law by suing various state officials or a private individual, before the enforcement of the new Texas law.

The decision of the Court was somewhat complex because of the split among justices. Overall:

- The Court held 8-1 that before the law is enforced, providers have the ability to sue executives of medical licensing boards. This was based on the possibility that there could be licensure discipline for professionals who violate the new abortion law. Only Justice Thomas dissented from this part of the decision, which was written by Justice Gorsuch.

- The Court unanimously held that state-court judges could not be sued to stop enforcement of the law, and dismissed them from the suit.

- In a 5-4 split the Court held that state court clerks (and the state attorney general) could not be brought into federal court as a way of challenging the law. This was based on the 11th Amendment, sovereign immunity, and an important precedent from 1908.2 Chief Justice Roberts wrote from the justices who were essentially in dissent (Justices Bryer, Kagan, and Sotomayor). Justice Sotomayor also wrote a dissent (joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan) urging that there should be some way for providers to test the constitutionality of the law before enforcement. Allowing an action against state court clerks would be a good way to do that. She also expressly noted the problem of the Texas law approach being used by other states to attack any number of constitutional rights.

- The Court unanimously dismissed (for lack of standing) the one private citizen who had been sued. He had signed a sworn statement that he did not intend to seek the damages against abortion providers under the Texas law.

- The Court declined again to stay the Texas law while it is being challenged. That is, it left standing the 5th Circuit order allowing the law to go into effect.

- In a second, related case, the Court dismissed, without deciding, the Biden administration’s request to become a party in the Texas abortion case.3

References

- Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, No. 21–463 (Dec. 10, 2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov /opinions/21pdf/21-463_new_8o6b.pdf.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

- U.S. v Texas, 21-588 (Dec. 10, 2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21-588 _c07d.pdf

Continue to: Re-evaluating the viability standard...

Re-evaluating the viability standard

The substantive abortion issue in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization is the constitutionality of the Mississippi Gestational Age Act, which allows abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy only for medical emergencies or severe fetal abnormality.29 This case is likely the most watched and controversial case of the Term. Many medical organizations have filed amicus curiae briefs, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists joined by the American Medical Association,30 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics,31 and the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists.32 The reason for all this attention is that the Court has accepted to resolve “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.” Thus, it represents a direct challenge to the trimester/viability structure of Roe.

It appears that there are 3 justices ready to outright overrule Roe, 3 that would uphold it as is, and 3 who are not in favor of Roe, but feel bound by precedent or are not in favor of a traumatic move. For that reason, there may be a narrow decision in this case. For example, the Court might find a procedural way to avoid directly deciding the abortion issue in this case, or it might uphold the right to abortion but change the viability standard. It is also true that predicting what the Court will do in controversial cases is a fool’s errand.

The complexity of reproductive rights and the ObGyn practice

These cases and policies affect the day-to-day practice of obstetrics. It is the most legally complex area of medical practice for several reasons. The law varies considerably from state to state. The clinician who practices both in California and across the border in Arizona will face substantially different laws, especially regarding the treatment of adolescents. And the reproductive rights laws in many states are a complicated mix of state statutes and state court decisions, with an overlay of federal statutes and court decisions, and a series of both state and federal regulations. This article demonstrates an additional complexity for practitioners—the continuous change in the law surrounding reproductive rights—and practice involving adolescent patients is especially difficult.

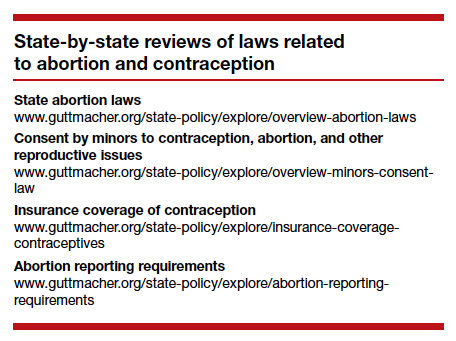

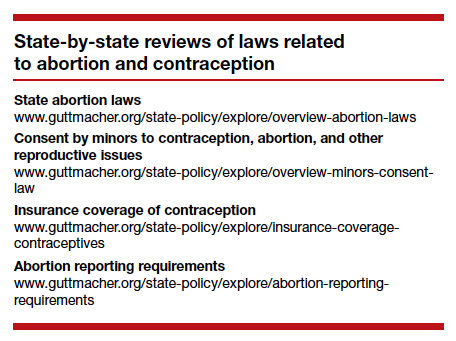

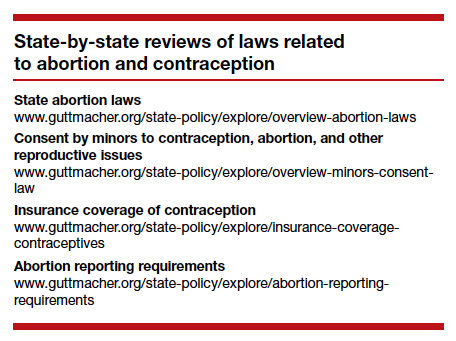

There are some good state-by-state reviews of laws related to abortion and contraception. We find the Guttmacher Institute particularly helpful. (See “State-by-state reviews of laws related to abortion and contraception”.) Although these are good resources, they are not the basis for legal practice with the current law in a state. The complexity and ever-changing nature of reproductive rights is one of the reasons we believe that it is important that anyone in active ObGyn practice maintain an ongoing professional relationship with a lawyer with expertise in this area of practice. This relationship should establish and update policies and procedures consistent with local law, consent and other forms, reporting of possible child abuse, and the like. An annual legal checkup may be as important for physicians as a physical checkup is for their patients.

Future outcomes

At the end of the Term, we will review the outcome of the cases noted above—and the possibility of follow-on cases. Whatever the Court does this Term, it will not be the end of the legal and political struggles over abortion and other reproductive issues. These questions deeply divide our society, and the cases and controversies reflect that continuing division. ●

- Buck v Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

- Id. at 207.

- Skinner v State of Oklahoma, ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942).

- Griswold v Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

- Eisenstadt v Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Harris v McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980).

- Williams v Zbaraz, 448 U.S 358 (1980).

- Webster v Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989).

- Rust v Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173 (1991).

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Carey v Population Services, 431 U.S. 678 (1977).

- Bellotti v Baird, 443 U.S. 622 (1979).

- Planned Parenthood of Kansas City v Ashcroft, 462 U.S. 476 (1983).

- Planned Parenthood of Northern New England v Ayotte, 546 U.S. 320 (2006).

- H.L. v Matheson, 450 U.S. 398 (1981).

- Hodgson v Minnesota, 497 U.S. 417 (1990).

- Ohio v Akron Center for Reproductive Health, 497 U.S. 502 (1990).

- Lambert v Wicklund, 520 U.S. 292 (1997).

- June Medical Services v Russo, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), https:// www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-1323_c07d.pdf.

- Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. 582 (2016).

- AMA v Becerra, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/american-medical -association-v-cochran.

- Becerra v Baltimore, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cochran-v-mayor-and-city-council-of-baltimore.

- Oregon v Becerra, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/oregon-v-cochran.

- Cameron v EMW Women’s Surgical Center, 20-601. https:// www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cameron-v-emw -womens-surgical-center-p-s-c.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

- Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, 21-463. https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/whole-womans-health-v -jackson.

- U.S. v Texas, 21-588. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files /cases/united-states-v-texas-3.

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/dobbs-v -jackson-womens-health-organization.

- Brief of Amici Curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists et al., Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 2021). https://www.acog.org/ -/media/project/acog/acogorg/files/advocacy/amicus -briefs/2021/20210920-dobbs-v-jwho-amicus-brief.pdf?la=e n&hash=717DFDD07A03B93A04490E66835BB8C5.

- Brief Amicus Curiae of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 20, 2021). https://www.supremecourt. gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/193019/20210920155508744 _41426%20pdf%20Chen.pdf.

- Brief Amicus Curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 2021). https://www.supremecourt .gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/185350/20210729163532595 _No.%2019-1392%20-%20American%20Association %20of%20Pro-Life%20Obstetricians%20and%20 Gynecologists%20-%20Amicus%20Brief%20in%20Support %20of%20Petitioner%20-%207-29-21.pdf.

There is now great interest in the Supreme Court’s handling of cases that involve a woman’s ability to have an abortion. Recent decisions, and those planned in the next few months will be the source of intense scrutiny. But the Court’s involvement in reproductive rights did not begin with abortion. In fact, the Supreme Court has a long history of controversial decisions dealing with reproductive rights.

Involuntary sterilization

A notable, even infamous, case was Buck v Bell (1927)—later discredited—in which the Court reviewed a state law that provided for the involuntary sterilization of the “feeble minded.”1 The 8-1 decision was that the state could choose to have such a law to protect the so-called genetic health of the state. The law was based on a theory of eugenics. The opinion by the highly respected Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes included the unfortunate conclusion, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”2 As mentioned, the law has since been thoroughly discredited. In 1942, the Court did come to a different result, holding in Skinner v Oklahoma that it was unconstitutional for a state to involuntarily sterilize “habitual criminals.”3

Contraception

Forty years after Buck, in Griswold v Connecticut, the Court reviewed a state law that prohibited the distribution of any drug or device used for contraception (even for married couples).4 In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the state law as violating a marital right of privacy. Beyond its specific holding, Griswold was important in several ways. First, a physician was raising the rights of patients (not specifically his own rights). This is notable because, ordinarily in court, litigants may argue their own rights, not the rights of others. This has been important in later reproductive rights cases because often it has been physicians raising and arguing the rights of patients.

A second interesting part of Griswold was the source of this constitutional right of privacy. The Constitution contains no express privacy provision. In Griswold, the Court found that the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 9th Amendments create the right to privacy in marital relations. Writing for the majority, Justice Douglas found that “emanations” from these amendments have “penumbras” that create a right of marital privacy.

Although Griswold was based on marital privacy, a few years later, in 1972, the Court essentially converted that right to one of reproductive privacy (“the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”) In Eisenstadt v Baird, the Court held that it was a violation of equal protection (the 14th Amendment) for a state to allow contraception to the married but deny it to an unmarried person.5

Continue to: Abortion...

Abortion

In 1971, the Court had heard arguments in 2 cases that raised issues regarding whether state laws prohibiting abortion were constitutional. The first oral argument in Roe v Wade is widely considered one of the worst oral arguments in modern history, and for several reasons the Court set the case for rehearing the following Term (October 1972). In January 1973, the Court decided Roe v Wade.6 The 7-2 decision was written by Justice Blackmun, who had at one point been the attorney for the Mayo Clinic and might be considered one of the first “health lawyers.” The Court held that the Constitution (perhaps in the 14th or 9th Amendment) includes a right of privacy that includes the right of a woman to choose to have, or not to have, an abortion. In implementing the right, the Court held that a state may impose only modest medical safeguards for the mother (eg, requiring that abortions be performed by a licensed physician). In the second trimester, to the point of viability, a state could impose only limitations on abortion that were reasonably directed to ensure the health of the mother. After a fetus was viable (could live outside the mother’s body), the state was free to regulate or prohibit abortions and protect the fetus. At the time, viability was approximately the beginning of the third trimester.6

The clear majority of the Court in Roe (7-2) may have suggested that there was not strong opposition to the decision. That, of course, was not the case. Legal and political conflict surrounding the case has been, and remains, intense. Since 1973, the Court has been called upon to decide many abortion cases, and each case seems to beget more controversy and still more cases.

Some of the legal objections to Roe and other abortion decisions are that the constitutional basis for the decision remains unclear—a specific right of privacy is not contained in the text of the Constitution. Several locations of a possible right of privacy have been mentioned by various justices, but “substantive due process” became the common constitutional basis for the right. Critics note that “substantive” due process (as opposed to procedural due process) is not mentioned in the Constitution, and it is short on clear guiding principles. Beyond those jurisprudential issues, of course, there were strong religious and philosophical objections to abortion. What followed Roe has been a long series of efforts to limit or discourage access to abortion, and the Supreme Court has had to decide a great many abortion cases (and a few contraception cases) over the last 50 years. Most years (except from 2008‒2013) the Court has heard, on average, at least one abortion case.

By way of examples, here are some of the issues related to abortion that the Court has decided:

- Payment and facilities. States and the federal government are not required to pay for abortions for women who cannot afford them or to provide facilities for abortion.7-10

- Informed consent. Some states’ special informed consent requirements for abortion were upheld, but complex consents that required the father’s participation were not.

- Ability to advertise. Prohibitions on advertisement of abortion services were struck down.

- Location. Requirements for hospital-only abortions (or similar regulations) were struck down.

- Anti-abortion protests. Several cases addressed guidelines involving demonstrations near abortion clinics.

Of particular importance was the case of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey—“Casey.”11 In 1992 that case reaffirmed the “essential” holding of Roe v Wade. A plurality in that case de-emphasized the trimester framework and applied an “undue burden” test on limitations on abortion. In the more recent cases argued before the Court, Casey is frequently referred to as specifically reaffirming, and therefore solidifying, Roe.

Consent for minors

There have been several cases since 1973 that involved contraceptives or abortions and “minors” (generally, adolescents aged <18 years, although there are some state-defined exceptions). These cases typically involve 2 issues: the right of minors to consent to treatment and the obligation of the physician to provide information to parents about treatment to their minor daughter. In 1977 the Court struck down a New York law that prohibited the distribution of contraceptives to minors.12 However, abortion issues involving minors have been more complicated. While the Court has struck down “2-parent” consent statutes,13 it has generally upheld 1-parent consent statutes, but only if those statutes contain a “judicial bypass” provision and an emergency medical provision.11,14,15 (This bypass allows a minor to “bypass” parental consent to abortion in some circumstances, and instead seek judicial authorization for an abortion.) Generally, the Court has upheld parental notification for abortions, with exceptions where it would be harmful to the minor who is seeking the abortion.16-19

Continue to: Who can perform an abortion...

Who can perform an abortion

Over the years there have also been several cases raising questions about the professionals who can perform abortions, their hospital privileges, and what facilities can perform abortions. Two of those cases in recent years have, for example, seen the Court strike down state statutes that required the physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at least in 1 nearby hospital.20,21 The basis for these decisions is that the admitting qualification is an “undue burden” because it serves almost no health purpose, while significantly limiting the number of professionals who can perform abortions.

Cases this Term

The current Term of the Court (officially the “October 2021 Term”) may be one of the most significant for reproductive rights in recent history. The Court accepted 6 abortion-related cases to hear. It dismissed 3 of those cases, which had become “moot” because the Biden administration changed the rules that had been legally challenged.22-24 It has heard arguments in the 3 (technically 4) remaining cases, in which decisions will be announced over the next several months.

The first of these cases (involving the Texas Heartbeat Act) raises very important, but vexing, procedural issues about a Texas abortion law. The second (Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson) is a direct challenge to Roe v Wade. The third case (Cameron v EMW Women’s Surgical Center) involves the narrow question of whether a state attorney general can intervene in a case to uphold a state abortion law when another state official refuses to defend the law.25 It is worthwhile taking a look at the first 2 of these cases.

Texas Heartbeat Act

In the first case (technically, it is 2 cases, as we will see), the Texas legislature adopted a law that prohibits abortions after there is a discernable heartbeat (around 6 weeks of pregnancy). The law precludes state officials from enforcing the law. Instead, it allows almost any private citizen to seek monetary damages ($10,000 plus fees) from anyone who performs an abortion or “aids and abets” an abortion. (This is in some ways similar to “private attorney general” actions found in the False Claims Act, and in some civil rights and labor laws.) This statute is clearly inconsistent with Roe in that it prohibits abortions before the end of the second trimester. If it were a usual law—a Texas law being enforced by state officials—federal courts would issue injunctions to state officials against enforcing the law. The difficulty with the Texas law (and its very purpose) is that there are procedural limitations in federal law that make it very difficult to find a path for federal courts to review the Texas statute quickly. For example, would federal courts enjoin every private citizen of the state? There is a longstanding Constitutional doctrine that precludes federal courts from enjoining state courts.26 Therefore, it is difficult to challenge the law before someone performing or aiding an abortion has been ordered to pay the private citizen who is enforcing it. In the interim, which could be months or even years, health care providers face uncertainty about continuing to provide abortion services. Some providers would stop providing abortion services, reducing the availability of those services.

Two cases challenge this Texas procedure. In the first, Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, 27 abortion providers seek to find some way through the procedural thicket to allow an immediate challenge to the statute. It is important because this technique of exclusive private enforcement could be used in any number of ways by the state to chill important constitutional rights (beyond abortion—to speech, to bear arms). In the second case involving the Texas law, U.S. v Texas, the federal government seeks to intervene in the case, which is another unusual procedure.28 The Court found these questions so important and difficult that it allowed 3 hours of argument (and 4 sets of lawyers). It seems likely that the Court will find a mechanism for allowing some early federal court review of individual enforcement of state laws, while minimizing harm to the state-national federalism that is at the heart of the Constitution.

For the recent procedural decisions in the Texas cases, see the “Current Court Decisions” box below.

On December 10, 2021, the Court handed down two decisions in reproductive freedom (abortion) cases, both involving the Texas abortion law (which prohibits most abortions after a fetal heartbeat can be detected and allows only private individuals to enforce the law). The more significant of the two cases, Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson,1 was the request of abortion providers (and others) to allow them to challenge the constitutionality of the Texas law by suing various state officials or a private individual, before the enforcement of the new Texas law.

The decision of the Court was somewhat complex because of the split among justices. Overall:

- The Court held 8-1 that before the law is enforced, providers have the ability to sue executives of medical licensing boards. This was based on the possibility that there could be licensure discipline for professionals who violate the new abortion law. Only Justice Thomas dissented from this part of the decision, which was written by Justice Gorsuch.

- The Court unanimously held that state-court judges could not be sued to stop enforcement of the law, and dismissed them from the suit.

- In a 5-4 split the Court held that state court clerks (and the state attorney general) could not be brought into federal court as a way of challenging the law. This was based on the 11th Amendment, sovereign immunity, and an important precedent from 1908.2 Chief Justice Roberts wrote from the justices who were essentially in dissent (Justices Bryer, Kagan, and Sotomayor). Justice Sotomayor also wrote a dissent (joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan) urging that there should be some way for providers to test the constitutionality of the law before enforcement. Allowing an action against state court clerks would be a good way to do that. She also expressly noted the problem of the Texas law approach being used by other states to attack any number of constitutional rights.

- The Court unanimously dismissed (for lack of standing) the one private citizen who had been sued. He had signed a sworn statement that he did not intend to seek the damages against abortion providers under the Texas law.

- The Court declined again to stay the Texas law while it is being challenged. That is, it left standing the 5th Circuit order allowing the law to go into effect.

- In a second, related case, the Court dismissed, without deciding, the Biden administration’s request to become a party in the Texas abortion case.3

References

- Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, No. 21–463 (Dec. 10, 2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov /opinions/21pdf/21-463_new_8o6b.pdf.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

- U.S. v Texas, 21-588 (Dec. 10, 2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21-588 _c07d.pdf

Continue to: Re-evaluating the viability standard...

Re-evaluating the viability standard

The substantive abortion issue in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization is the constitutionality of the Mississippi Gestational Age Act, which allows abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy only for medical emergencies or severe fetal abnormality.29 This case is likely the most watched and controversial case of the Term. Many medical organizations have filed amicus curiae briefs, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists joined by the American Medical Association,30 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics,31 and the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists.32 The reason for all this attention is that the Court has accepted to resolve “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.” Thus, it represents a direct challenge to the trimester/viability structure of Roe.

It appears that there are 3 justices ready to outright overrule Roe, 3 that would uphold it as is, and 3 who are not in favor of Roe, but feel bound by precedent or are not in favor of a traumatic move. For that reason, there may be a narrow decision in this case. For example, the Court might find a procedural way to avoid directly deciding the abortion issue in this case, or it might uphold the right to abortion but change the viability standard. It is also true that predicting what the Court will do in controversial cases is a fool’s errand.

The complexity of reproductive rights and the ObGyn practice

These cases and policies affect the day-to-day practice of obstetrics. It is the most legally complex area of medical practice for several reasons. The law varies considerably from state to state. The clinician who practices both in California and across the border in Arizona will face substantially different laws, especially regarding the treatment of adolescents. And the reproductive rights laws in many states are a complicated mix of state statutes and state court decisions, with an overlay of federal statutes and court decisions, and a series of both state and federal regulations. This article demonstrates an additional complexity for practitioners—the continuous change in the law surrounding reproductive rights—and practice involving adolescent patients is especially difficult.

There are some good state-by-state reviews of laws related to abortion and contraception. We find the Guttmacher Institute particularly helpful. (See “State-by-state reviews of laws related to abortion and contraception”.) Although these are good resources, they are not the basis for legal practice with the current law in a state. The complexity and ever-changing nature of reproductive rights is one of the reasons we believe that it is important that anyone in active ObGyn practice maintain an ongoing professional relationship with a lawyer with expertise in this area of practice. This relationship should establish and update policies and procedures consistent with local law, consent and other forms, reporting of possible child abuse, and the like. An annual legal checkup may be as important for physicians as a physical checkup is for their patients.

Future outcomes

At the end of the Term, we will review the outcome of the cases noted above—and the possibility of follow-on cases. Whatever the Court does this Term, it will not be the end of the legal and political struggles over abortion and other reproductive issues. These questions deeply divide our society, and the cases and controversies reflect that continuing division. ●

There is now great interest in the Supreme Court’s handling of cases that involve a woman’s ability to have an abortion. Recent decisions, and those planned in the next few months will be the source of intense scrutiny. But the Court’s involvement in reproductive rights did not begin with abortion. In fact, the Supreme Court has a long history of controversial decisions dealing with reproductive rights.

Involuntary sterilization

A notable, even infamous, case was Buck v Bell (1927)—later discredited—in which the Court reviewed a state law that provided for the involuntary sterilization of the “feeble minded.”1 The 8-1 decision was that the state could choose to have such a law to protect the so-called genetic health of the state. The law was based on a theory of eugenics. The opinion by the highly respected Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes included the unfortunate conclusion, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”2 As mentioned, the law has since been thoroughly discredited. In 1942, the Court did come to a different result, holding in Skinner v Oklahoma that it was unconstitutional for a state to involuntarily sterilize “habitual criminals.”3

Contraception

Forty years after Buck, in Griswold v Connecticut, the Court reviewed a state law that prohibited the distribution of any drug or device used for contraception (even for married couples).4 In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the state law as violating a marital right of privacy. Beyond its specific holding, Griswold was important in several ways. First, a physician was raising the rights of patients (not specifically his own rights). This is notable because, ordinarily in court, litigants may argue their own rights, not the rights of others. This has been important in later reproductive rights cases because often it has been physicians raising and arguing the rights of patients.

A second interesting part of Griswold was the source of this constitutional right of privacy. The Constitution contains no express privacy provision. In Griswold, the Court found that the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 9th Amendments create the right to privacy in marital relations. Writing for the majority, Justice Douglas found that “emanations” from these amendments have “penumbras” that create a right of marital privacy.

Although Griswold was based on marital privacy, a few years later, in 1972, the Court essentially converted that right to one of reproductive privacy (“the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”) In Eisenstadt v Baird, the Court held that it was a violation of equal protection (the 14th Amendment) for a state to allow contraception to the married but deny it to an unmarried person.5

Continue to: Abortion...

Abortion

In 1971, the Court had heard arguments in 2 cases that raised issues regarding whether state laws prohibiting abortion were constitutional. The first oral argument in Roe v Wade is widely considered one of the worst oral arguments in modern history, and for several reasons the Court set the case for rehearing the following Term (October 1972). In January 1973, the Court decided Roe v Wade.6 The 7-2 decision was written by Justice Blackmun, who had at one point been the attorney for the Mayo Clinic and might be considered one of the first “health lawyers.” The Court held that the Constitution (perhaps in the 14th or 9th Amendment) includes a right of privacy that includes the right of a woman to choose to have, or not to have, an abortion. In implementing the right, the Court held that a state may impose only modest medical safeguards for the mother (eg, requiring that abortions be performed by a licensed physician). In the second trimester, to the point of viability, a state could impose only limitations on abortion that were reasonably directed to ensure the health of the mother. After a fetus was viable (could live outside the mother’s body), the state was free to regulate or prohibit abortions and protect the fetus. At the time, viability was approximately the beginning of the third trimester.6

The clear majority of the Court in Roe (7-2) may have suggested that there was not strong opposition to the decision. That, of course, was not the case. Legal and political conflict surrounding the case has been, and remains, intense. Since 1973, the Court has been called upon to decide many abortion cases, and each case seems to beget more controversy and still more cases.

Some of the legal objections to Roe and other abortion decisions are that the constitutional basis for the decision remains unclear—a specific right of privacy is not contained in the text of the Constitution. Several locations of a possible right of privacy have been mentioned by various justices, but “substantive due process” became the common constitutional basis for the right. Critics note that “substantive” due process (as opposed to procedural due process) is not mentioned in the Constitution, and it is short on clear guiding principles. Beyond those jurisprudential issues, of course, there were strong religious and philosophical objections to abortion. What followed Roe has been a long series of efforts to limit or discourage access to abortion, and the Supreme Court has had to decide a great many abortion cases (and a few contraception cases) over the last 50 years. Most years (except from 2008‒2013) the Court has heard, on average, at least one abortion case.

By way of examples, here are some of the issues related to abortion that the Court has decided:

- Payment and facilities. States and the federal government are not required to pay for abortions for women who cannot afford them or to provide facilities for abortion.7-10

- Informed consent. Some states’ special informed consent requirements for abortion were upheld, but complex consents that required the father’s participation were not.

- Ability to advertise. Prohibitions on advertisement of abortion services were struck down.

- Location. Requirements for hospital-only abortions (or similar regulations) were struck down.

- Anti-abortion protests. Several cases addressed guidelines involving demonstrations near abortion clinics.

Of particular importance was the case of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey—“Casey.”11 In 1992 that case reaffirmed the “essential” holding of Roe v Wade. A plurality in that case de-emphasized the trimester framework and applied an “undue burden” test on limitations on abortion. In the more recent cases argued before the Court, Casey is frequently referred to as specifically reaffirming, and therefore solidifying, Roe.

Consent for minors

There have been several cases since 1973 that involved contraceptives or abortions and “minors” (generally, adolescents aged <18 years, although there are some state-defined exceptions). These cases typically involve 2 issues: the right of minors to consent to treatment and the obligation of the physician to provide information to parents about treatment to their minor daughter. In 1977 the Court struck down a New York law that prohibited the distribution of contraceptives to minors.12 However, abortion issues involving minors have been more complicated. While the Court has struck down “2-parent” consent statutes,13 it has generally upheld 1-parent consent statutes, but only if those statutes contain a “judicial bypass” provision and an emergency medical provision.11,14,15 (This bypass allows a minor to “bypass” parental consent to abortion in some circumstances, and instead seek judicial authorization for an abortion.) Generally, the Court has upheld parental notification for abortions, with exceptions where it would be harmful to the minor who is seeking the abortion.16-19

Continue to: Who can perform an abortion...

Who can perform an abortion

Over the years there have also been several cases raising questions about the professionals who can perform abortions, their hospital privileges, and what facilities can perform abortions. Two of those cases in recent years have, for example, seen the Court strike down state statutes that required the physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at least in 1 nearby hospital.20,21 The basis for these decisions is that the admitting qualification is an “undue burden” because it serves almost no health purpose, while significantly limiting the number of professionals who can perform abortions.

Cases this Term

The current Term of the Court (officially the “October 2021 Term”) may be one of the most significant for reproductive rights in recent history. The Court accepted 6 abortion-related cases to hear. It dismissed 3 of those cases, which had become “moot” because the Biden administration changed the rules that had been legally challenged.22-24 It has heard arguments in the 3 (technically 4) remaining cases, in which decisions will be announced over the next several months.

The first of these cases (involving the Texas Heartbeat Act) raises very important, but vexing, procedural issues about a Texas abortion law. The second (Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson) is a direct challenge to Roe v Wade. The third case (Cameron v EMW Women’s Surgical Center) involves the narrow question of whether a state attorney general can intervene in a case to uphold a state abortion law when another state official refuses to defend the law.25 It is worthwhile taking a look at the first 2 of these cases.

Texas Heartbeat Act

In the first case (technically, it is 2 cases, as we will see), the Texas legislature adopted a law that prohibits abortions after there is a discernable heartbeat (around 6 weeks of pregnancy). The law precludes state officials from enforcing the law. Instead, it allows almost any private citizen to seek monetary damages ($10,000 plus fees) from anyone who performs an abortion or “aids and abets” an abortion. (This is in some ways similar to “private attorney general” actions found in the False Claims Act, and in some civil rights and labor laws.) This statute is clearly inconsistent with Roe in that it prohibits abortions before the end of the second trimester. If it were a usual law—a Texas law being enforced by state officials—federal courts would issue injunctions to state officials against enforcing the law. The difficulty with the Texas law (and its very purpose) is that there are procedural limitations in federal law that make it very difficult to find a path for federal courts to review the Texas statute quickly. For example, would federal courts enjoin every private citizen of the state? There is a longstanding Constitutional doctrine that precludes federal courts from enjoining state courts.26 Therefore, it is difficult to challenge the law before someone performing or aiding an abortion has been ordered to pay the private citizen who is enforcing it. In the interim, which could be months or even years, health care providers face uncertainty about continuing to provide abortion services. Some providers would stop providing abortion services, reducing the availability of those services.

Two cases challenge this Texas procedure. In the first, Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, 27 abortion providers seek to find some way through the procedural thicket to allow an immediate challenge to the statute. It is important because this technique of exclusive private enforcement could be used in any number of ways by the state to chill important constitutional rights (beyond abortion—to speech, to bear arms). In the second case involving the Texas law, U.S. v Texas, the federal government seeks to intervene in the case, which is another unusual procedure.28 The Court found these questions so important and difficult that it allowed 3 hours of argument (and 4 sets of lawyers). It seems likely that the Court will find a mechanism for allowing some early federal court review of individual enforcement of state laws, while minimizing harm to the state-national federalism that is at the heart of the Constitution.

For the recent procedural decisions in the Texas cases, see the “Current Court Decisions” box below.

On December 10, 2021, the Court handed down two decisions in reproductive freedom (abortion) cases, both involving the Texas abortion law (which prohibits most abortions after a fetal heartbeat can be detected and allows only private individuals to enforce the law). The more significant of the two cases, Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson,1 was the request of abortion providers (and others) to allow them to challenge the constitutionality of the Texas law by suing various state officials or a private individual, before the enforcement of the new Texas law.

The decision of the Court was somewhat complex because of the split among justices. Overall:

- The Court held 8-1 that before the law is enforced, providers have the ability to sue executives of medical licensing boards. This was based on the possibility that there could be licensure discipline for professionals who violate the new abortion law. Only Justice Thomas dissented from this part of the decision, which was written by Justice Gorsuch.

- The Court unanimously held that state-court judges could not be sued to stop enforcement of the law, and dismissed them from the suit.

- In a 5-4 split the Court held that state court clerks (and the state attorney general) could not be brought into federal court as a way of challenging the law. This was based on the 11th Amendment, sovereign immunity, and an important precedent from 1908.2 Chief Justice Roberts wrote from the justices who were essentially in dissent (Justices Bryer, Kagan, and Sotomayor). Justice Sotomayor also wrote a dissent (joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan) urging that there should be some way for providers to test the constitutionality of the law before enforcement. Allowing an action against state court clerks would be a good way to do that. She also expressly noted the problem of the Texas law approach being used by other states to attack any number of constitutional rights.

- The Court unanimously dismissed (for lack of standing) the one private citizen who had been sued. He had signed a sworn statement that he did not intend to seek the damages against abortion providers under the Texas law.

- The Court declined again to stay the Texas law while it is being challenged. That is, it left standing the 5th Circuit order allowing the law to go into effect.

- In a second, related case, the Court dismissed, without deciding, the Biden administration’s request to become a party in the Texas abortion case.3

References

- Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, No. 21–463 (Dec. 10, 2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov /opinions/21pdf/21-463_new_8o6b.pdf.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

- U.S. v Texas, 21-588 (Dec. 10, 2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21-588 _c07d.pdf

Continue to: Re-evaluating the viability standard...

Re-evaluating the viability standard

The substantive abortion issue in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization is the constitutionality of the Mississippi Gestational Age Act, which allows abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy only for medical emergencies or severe fetal abnormality.29 This case is likely the most watched and controversial case of the Term. Many medical organizations have filed amicus curiae briefs, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists joined by the American Medical Association,30 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics,31 and the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists.32 The reason for all this attention is that the Court has accepted to resolve “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.” Thus, it represents a direct challenge to the trimester/viability structure of Roe.

It appears that there are 3 justices ready to outright overrule Roe, 3 that would uphold it as is, and 3 who are not in favor of Roe, but feel bound by precedent or are not in favor of a traumatic move. For that reason, there may be a narrow decision in this case. For example, the Court might find a procedural way to avoid directly deciding the abortion issue in this case, or it might uphold the right to abortion but change the viability standard. It is also true that predicting what the Court will do in controversial cases is a fool’s errand.

The complexity of reproductive rights and the ObGyn practice

These cases and policies affect the day-to-day practice of obstetrics. It is the most legally complex area of medical practice for several reasons. The law varies considerably from state to state. The clinician who practices both in California and across the border in Arizona will face substantially different laws, especially regarding the treatment of adolescents. And the reproductive rights laws in many states are a complicated mix of state statutes and state court decisions, with an overlay of federal statutes and court decisions, and a series of both state and federal regulations. This article demonstrates an additional complexity for practitioners—the continuous change in the law surrounding reproductive rights—and practice involving adolescent patients is especially difficult.

There are some good state-by-state reviews of laws related to abortion and contraception. We find the Guttmacher Institute particularly helpful. (See “State-by-state reviews of laws related to abortion and contraception”.) Although these are good resources, they are not the basis for legal practice with the current law in a state. The complexity and ever-changing nature of reproductive rights is one of the reasons we believe that it is important that anyone in active ObGyn practice maintain an ongoing professional relationship with a lawyer with expertise in this area of practice. This relationship should establish and update policies and procedures consistent with local law, consent and other forms, reporting of possible child abuse, and the like. An annual legal checkup may be as important for physicians as a physical checkup is for their patients.

Future outcomes

At the end of the Term, we will review the outcome of the cases noted above—and the possibility of follow-on cases. Whatever the Court does this Term, it will not be the end of the legal and political struggles over abortion and other reproductive issues. These questions deeply divide our society, and the cases and controversies reflect that continuing division. ●

- Buck v Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

- Id. at 207.

- Skinner v State of Oklahoma, ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942).

- Griswold v Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

- Eisenstadt v Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Harris v McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980).

- Williams v Zbaraz, 448 U.S 358 (1980).

- Webster v Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989).

- Rust v Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173 (1991).

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Carey v Population Services, 431 U.S. 678 (1977).

- Bellotti v Baird, 443 U.S. 622 (1979).

- Planned Parenthood of Kansas City v Ashcroft, 462 U.S. 476 (1983).

- Planned Parenthood of Northern New England v Ayotte, 546 U.S. 320 (2006).

- H.L. v Matheson, 450 U.S. 398 (1981).

- Hodgson v Minnesota, 497 U.S. 417 (1990).

- Ohio v Akron Center for Reproductive Health, 497 U.S. 502 (1990).

- Lambert v Wicklund, 520 U.S. 292 (1997).

- June Medical Services v Russo, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), https:// www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-1323_c07d.pdf.

- Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. 582 (2016).

- AMA v Becerra, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/american-medical -association-v-cochran.

- Becerra v Baltimore, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cochran-v-mayor-and-city-council-of-baltimore.

- Oregon v Becerra, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/oregon-v-cochran.

- Cameron v EMW Women’s Surgical Center, 20-601. https:// www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cameron-v-emw -womens-surgical-center-p-s-c.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

- Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, 21-463. https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/whole-womans-health-v -jackson.

- U.S. v Texas, 21-588. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files /cases/united-states-v-texas-3.

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/dobbs-v -jackson-womens-health-organization.

- Brief of Amici Curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists et al., Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 2021). https://www.acog.org/ -/media/project/acog/acogorg/files/advocacy/amicus -briefs/2021/20210920-dobbs-v-jwho-amicus-brief.pdf?la=e n&hash=717DFDD07A03B93A04490E66835BB8C5.

- Brief Amicus Curiae of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 20, 2021). https://www.supremecourt. gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/193019/20210920155508744 _41426%20pdf%20Chen.pdf.

- Brief Amicus Curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 2021). https://www.supremecourt .gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/185350/20210729163532595 _No.%2019-1392%20-%20American%20Association %20of%20Pro-Life%20Obstetricians%20and%20 Gynecologists%20-%20Amicus%20Brief%20in%20Support %20of%20Petitioner%20-%207-29-21.pdf.

- Buck v Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

- Id. at 207.

- Skinner v State of Oklahoma, ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942).

- Griswold v Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

- Eisenstadt v Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Harris v McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980).

- Williams v Zbaraz, 448 U.S 358 (1980).

- Webster v Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989).

- Rust v Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173 (1991).

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Carey v Population Services, 431 U.S. 678 (1977).

- Bellotti v Baird, 443 U.S. 622 (1979).

- Planned Parenthood of Kansas City v Ashcroft, 462 U.S. 476 (1983).

- Planned Parenthood of Northern New England v Ayotte, 546 U.S. 320 (2006).

- H.L. v Matheson, 450 U.S. 398 (1981).

- Hodgson v Minnesota, 497 U.S. 417 (1990).

- Ohio v Akron Center for Reproductive Health, 497 U.S. 502 (1990).

- Lambert v Wicklund, 520 U.S. 292 (1997).

- June Medical Services v Russo, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), https:// www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-1323_c07d.pdf.

- Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. 582 (2016).

- AMA v Becerra, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/american-medical -association-v-cochran.

- Becerra v Baltimore, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cochran-v-mayor-and-city-council-of-baltimore.

- Oregon v Becerra, dismissed May 17, 2021, https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/oregon-v-cochran.

- Cameron v EMW Women’s Surgical Center, 20-601. https:// www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cameron-v-emw -womens-surgical-center-p-s-c.

- Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

- Whole Woman’s Health v Jackson, 21-463. https://www .scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/whole-womans-health-v -jackson.

- U.S. v Texas, 21-588. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files /cases/united-states-v-texas-3.

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/dobbs-v -jackson-womens-health-organization.

- Brief of Amici Curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists et al., Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 2021). https://www.acog.org/ -/media/project/acog/acogorg/files/advocacy/amicus -briefs/2021/20210920-dobbs-v-jwho-amicus-brief.pdf?la=e n&hash=717DFDD07A03B93A04490E66835BB8C5.

- Brief Amicus Curiae of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 20, 2021). https://www.supremecourt. gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/193019/20210920155508744 _41426%20pdf%20Chen.pdf.

- Brief Amicus Curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization (Sep. 2021). https://www.supremecourt .gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/185350/20210729163532595 _No.%2019-1392%20-%20American%20Association %20of%20Pro-Life%20Obstetricians%20and%20 Gynecologists%20-%20Amicus%20Brief%20in%20Support %20of%20Petitioner%20-%207-29-21.pdf.