User login

Over the last 3 decades, abundant evidence has demonstrated the association between surgical volume and outcomes. Patients operated on by high-volume surgeons and at high-volume hospitals have superior outcomes.

Surgical volume in gynecology

The association between both hospital and surgeon volume and outcomes has been explored across a number of gynecologic procedures.3 A meta-analysis that included 741,000 patients found that low-volume surgeons had an increased rate of complications overall, a higher rate of intraoperative complications, and a higher rate of postoperative complications compared with high-volume surgeons. While there was no association between volume and mortality overall, when limited to gynecologic oncology studies, low surgeon volume was associated with increased perioperative mortality.3

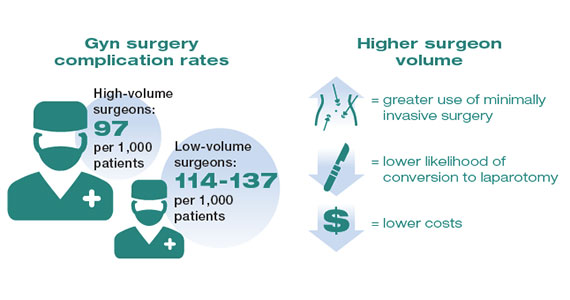

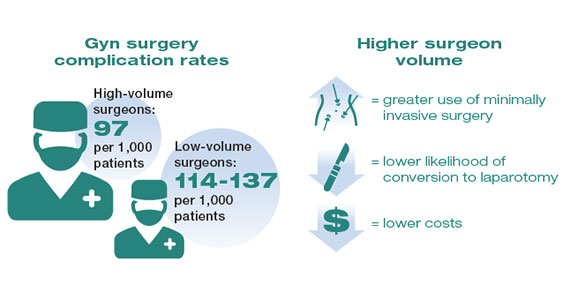

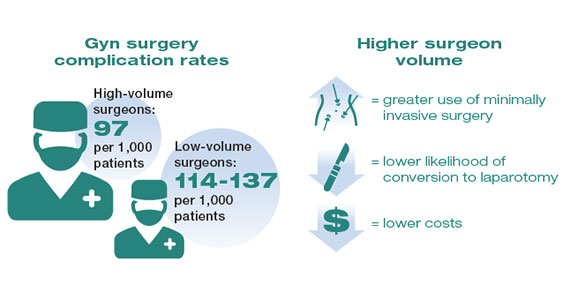

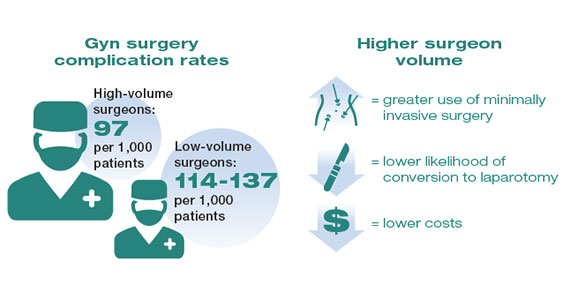

While these studies demonstrated a statistically significant association between surgeon volume and perioperative outcomes, the magnitude of the effect is modest compared with other higher-risk procedures associated with greater perioperative morbidity. For example, in a large study that examined oncologic and cardiovascular surgery, perioperative mortality in patients who underwent pancreatic resection was reduced from 15% for low-volume surgeons to 5% for high-volume surgeons.1 By contrast, for gynecologic surgery, complications occurred in 97 per 1,000 patients operated on by high-volume surgeons compared with between 114 and 137 per 1,000 for low-volume surgeons. Thus, to avoid 1 in-hospital complication, 30 surgeries performed by low-volume surgeons would need to be moved to high-volume surgeons. For intraoperative complications, 38 patients would need to be moved from low- to high-volume surgeons to prevent 1 such complication.3 In addition to morbidity and mortality, higher surgeon volume is associated with greater use of minimally invasive surgery, a lower likelihood of conversion to laparotomy, and lower costs.3

Similarly, hospital volume also has been associated with outcomes for gynecologic surgery.4 In a report of patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy, the authors found that the complication rate was 18% lower for patients at high- versus low-volume hospitals. In addition, cost was lower at the high-volume centers.4 Like surgeon volume, the magnitude of the differential in outcomes between high- and low-volume hospitals is often modest.4

While most studies have focused on short-term outcomes, surgical volume appears also to be associated with longer-term outcomes. For gynecologic cancer, studies have demonstrated an association between hospital volume and survival for ovarian and cervical cancer.5-7 A large report of centers across the United States found that the 5-year survival rate increased from 39% for patients treated at low-volume centers to 51% at the highest-volume hospitals.5 In urogynecology, surgeon volume has been associated with midurethral sling revision. One study noted that after an individual surgeon performed 50 procedures a year, each additional case was associated with a decline in the rate of sling revision.8 One could argue that these longer-term end points may be the measures that matter most to patients.

Although the magnitude of the association between surgical volume and outcomes in gynecology appears to be relatively modest, outcomes for very-low-volume (VLV) surgeons are substantially worse. An analysis of more than 430,000 patients who underwent hysterectomy compared outcomes between VLV surgeons (characterized as surgeons who performed only 1 hysterectomy in the prior year) and other gynecologic surgeons. The overall complication rate was 32% in VLV surgeons compared with 10% among other surgeons, while the perioperative mortality rate was 2.5% versus 0.2% in the 2 groups, respectively. Likely reflecting changing practice patterns in gynecology, a sizable number of surgeons were classified as VLV physicians.9

Continue to: Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume...

Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume

The large body of literature on volume and outcomes has led to a number of public health initiatives aimed at reducing perioperative morbidity and mortality. Broadly, these efforts focus on regionalization of care, targeted quality improvement, and the development of minimum volume standards. Each strategy holds promise but also the potential to lead to unwanted consequences.

Regionalization of care

Recognition of the volume-outcomes paradigm has led to efforts to regionalize care for complex procedures to high-volume surgeons and centers.10 A cohort study of surgical patterns of care for Medicare recipients who underwent cancer resections or abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from 1999 to 2008 demonstrated these shifting practice patterns. For example, in 1999–2000, pancreatectomy was performed in 1,308 hospitals, with a median case volume of 5 procedures per year. By 2007–2008, the number of hospitals in which pancreatectomy was performed declined to 978, and the median case volume rose to 16 procedures per year. Importantly, over this time period, risk-adjusted mortality for pancreatectomy declined by 19%, and increased hospital volume was responsible for more than two-thirds of the decline in mortality.10

There has similarly been a gradual concentration of some gynecologic procedures to higher-volume surgeons and centers.11,12 Among patients undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in New York State, 845 surgeons with a mean case volume of 3 procedures per year treated patients in 2000. By 2014, the number of surgeons who performed these operations declined to 317 while mean annual case volume rose to 10 procedures per year. The number of hospitals in which women with endometrial cancer were treated declined from 182 to 98 over the same time period.11 Similar trends were noted for patients undergoing ovarian cancer resection.12 While patterns of gynecologic care for some surgical procedures have clearly changed, it has been more difficult to link these changes to improvements in outcomes.11,12

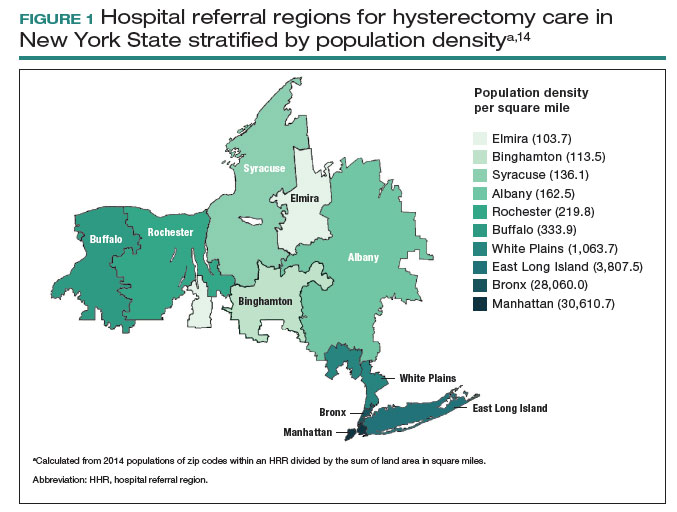

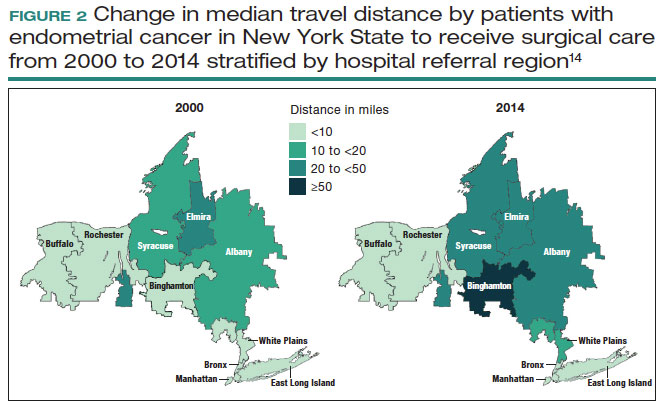

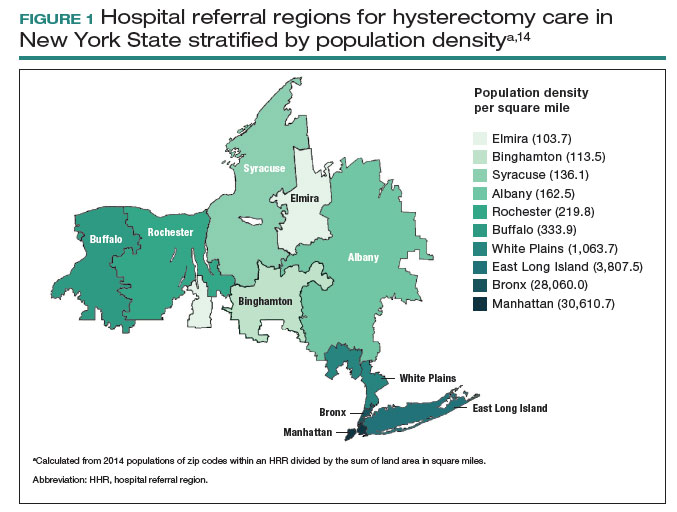

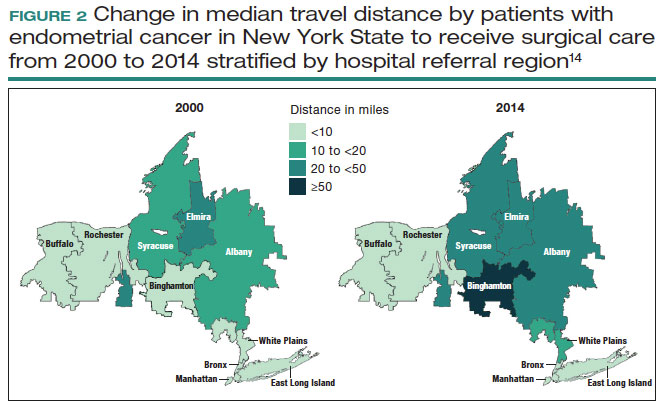

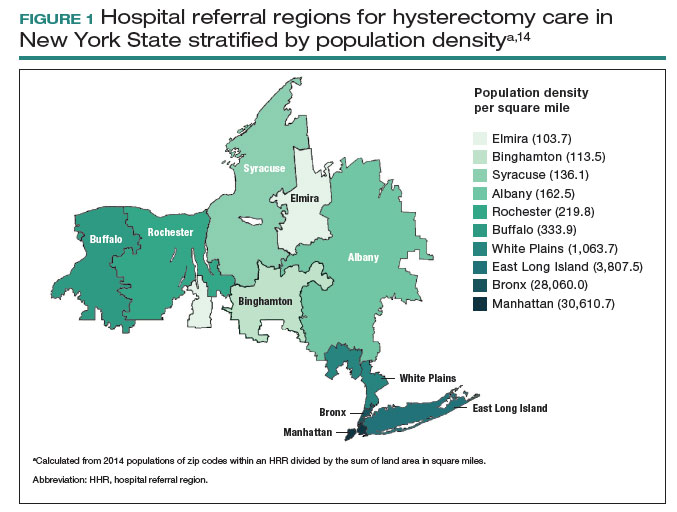

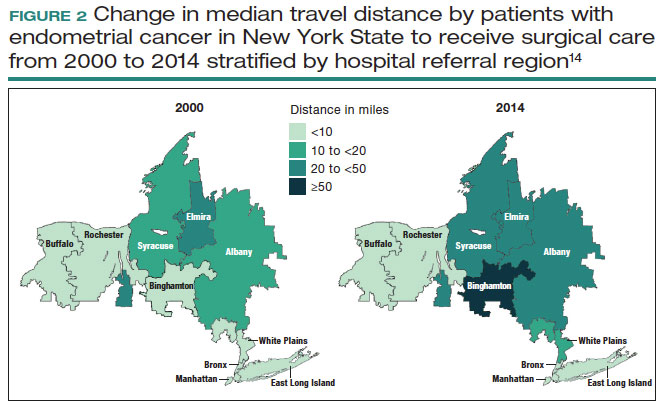

Despite the intuitive appeal of regionalization of surgical care, such a strategy has a number of limitations and practical challenges. Not surprisingly, limiting the number of surgeons and hospitals that perform a given procedure necessitates that patients travel a greater distance to obtain necessary surgical care.13,14 An analysis of endometrial cancer patients in New York State stratified patients based on their area of residence into 10 hospital referral regions (HRRs), which represent health care markets for tertiary medical care. From 2000 to 2014, the distance patients traveled to receive their surgical care increased in all of the HRRs studied. This was most pronounced in 1 of the HRRs in which the median travel distance rose by 47 miles over the 15-year period (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 2).14

Whether patients are willing to travel for care remains a matter of debate and depends on the disease, the surgical procedure, and the anticipated benefit associated with a longer travel distance.15,16 In a discrete choice experiment, 100 participants were given a hypothetical scenario in which they had potentially resectable pancreatic cancer; they were queried on their willingness to travel for care based on varying differences in mortality between a local and regional hospital.15 When mortality at the local hospital was double that of the regional hospital (6% vs 3%), 45% of patients chose to remain at the local hospital. When the differential increased to a 4 times greater mortality at the local hospital (12% vs 3%), 23% of patients still chose to remain at the local hospital.15

A similar study asked patients with ovarian neoplasms whether they would travel 50 miles to a regional center for surgery based on some degree of increased 5-year survival.16 Overall, 79% of patients would travel for a 4% improvement in survival while 97% would travel for a 12% improvement in survival.16

Lastly, a number of studies have shown that regionalization of surgical care disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients and those with low socioeconomic status.12,13,17 A simulation study on the effect of regionalizing care for pancreatectomy noted that using a hospital volume threshold of 20 procedures per year, a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic patients than White patients would be required to travel to a higher-volume center.13 Similarly, Medicaid recipients were more likely to be affected.13 Despite the inequities in who must travel for regionalized care, prior work has suggested that regionalization of cancer care to high-volume centers may reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival for some cancers.18

Targeted quality improvement

Realizing the practical limitations of regionalization of care, an alternative strategy is to improve the quality of care at low-volume hospitals.5,19 Quality of care and surgical volume often are correlated, and the delivery of high-quality care can mitigate some of the influence of surgical volume on outcomes.

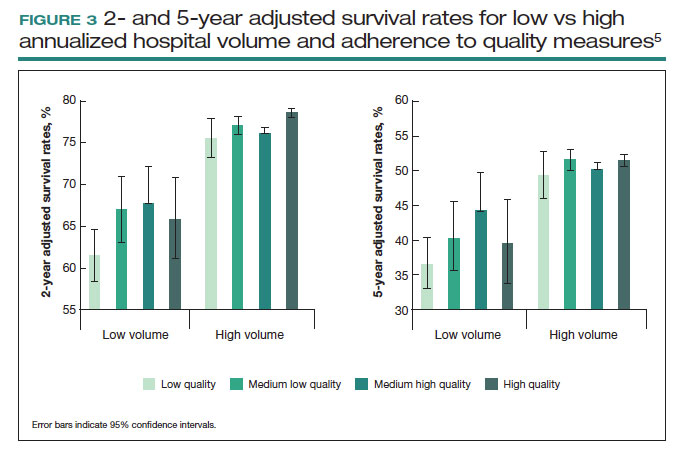

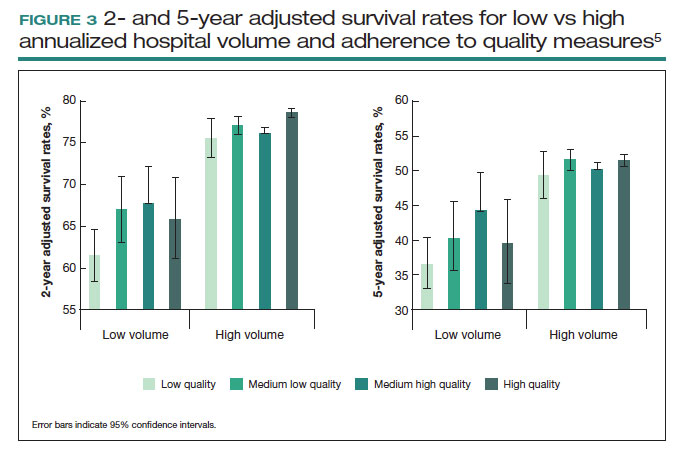

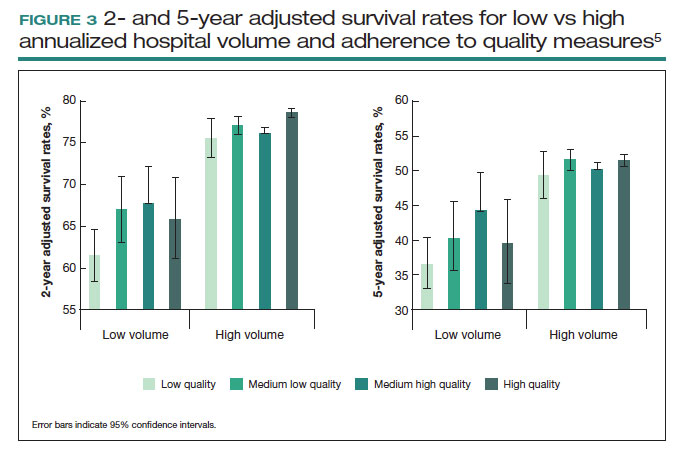

These principles were demonstrated in a study of more than 100,000 patients with ovarian cancer that stratified treating hospitals into volume quintiles.5 As expected, survival (both 2- and 5-year) was highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals (FIGURE 3).5 Similarly, quality of care, measured through adherence to various process measures, was also highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals. Interestingly, in the second-fourth volume quintile hospitals, there was substantial variation in adherence to quality metrics. Among hospitals with higher quality care, an improved survival was noted compared with lower quality care hospitals within the same volume quintile. Survival at high-quality, intermediate-volume hospitals approached that of the high-volume quintile hospitals.5

These findings highlight the importance of quality of care as well as the complex interplay of surgical volume and other factors.20 Many have argued that it may be more appropriate to measure quality of care and past performance and outcomes rather than surgical volume.21

Continue to: Minimum volume standards...

Minimum volume standards

While efforts to regionalize surgical care have gradually evolved, calls have been growing to formalize policies that limit the performance of some procedures to surgeons and centers that meet a minimum volume threshold or standard.21 One such effort, based on consensus from 3 academic hospital systems, was a campaign for hospitals to “Take the Volume Pledge.”21 The campaign’s goal is to encourage health care systems to restrict the performance of 10 procedures to surgeons and hospitals within their systems that meet a minimum volume standard for the given operations.21 In essence, procedures would be restricted for low-volume providers and centers and triaged to higher-volume surgeons and hospitals within a given health care system.21

Proponents of the Volume Pledge argue that it is a relatively straightforward way to align patients and providers to optimize outcomes. The Volume Pledge focuses on larger hospital systems and encourages referral within the given system, thus mitigating competitive and financial concerns about referring patients to outside providers. Those who have argued against the Volume Pledge point out that the volume cut points chosen are somewhat arbitrary, that these policies have the potential to negatively impact rural hospitals and those serving smaller communities, and that quality is a more appropriate metric than volume.22 The Volume Pledge does not include any gynecologic procedures, and to date it has met with only limited success.23

Perhaps more directly applicable to gynecologic surgeons are ongoing national trends to base hospital credentialing on surgical volume. In essence, individual surgeons must demonstrate that they have performed a minimum number of procedures to obtain or retain privileges.24,25 While there is strong evidence of the association between volume and outcomes for some complex surgical procedures, linking volume to credentialing has a number of potential pitfalls. Studies of surgical outcomes based on volume represent average performance, and many low-volume providers have better-than-expected outcomes. Volume measures typically represent recent performance; it is difficult to measure the overall experience of individual surgeons. Similarly, surgical outcomes depend on both the surgeon and the system in which the surgeon operates. It is difficult, if not impossible, to account for differences in the environment in which a surgeon works.25

A study of gynecologic surgeons who performed hysterectomy in New York State demonstrates many of the complexities of volume-based credentialing.26 In a cohort of more than55,000 patients who underwent abdominal hysterectomy, there was a strong association between low surgeon volume and a higher-than-expected rate of complications. If one were to consider limiting privileges to even the lowest-volume providers, there would be a significant impact on the surgical workforce. In this cohort, limiting credentialing to the lowest-volume providers, those who performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year would restrict the privileges of 17.5% of the surgeons in the cohort. Further, in this low-volume cohort that performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year, 69% of the surgeons actually had outcomes that were better than predicted.26 These data highlight not only the difficulty of applying averages to individual surgeons but also the profound impact that policy changes could have on the practice of gynecologic surgery.

Volume-outcomes paradigm discussions continue

The association between higher surgeon and hospital procedural volume for gynecologic surgeries and improved outcomes now has been convincingly demonstrated. With this knowledge, over the last decade the patterns of care for patients undergoing gynecologic surgery have clearly shifted, and these operations are now more commonly being performed by a smaller number of physicians and at fewer hospitals.

While efforts to improve quality are clearly important, many policy interventions, such as regionalization of care, have untoward consequences that must be considered. As we move forward, it will be essential to ensure that there is a robust debate among patients, providers, and policymakers on the merits of public health policies based on the volume-outcomes paradigm. ●

- Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117-2127.

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:11281137.

- Mowat A, Maher C, Ballard E. Surgical outcomes for low-volume vs high-volume surgeons in gynecology surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:21-33.

- Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effect of surgical volume on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:709-716.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Association of hospital volume and quality of care with survival for ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:545-553.

- Cliby WA, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Ovarian cancer in the United States: contemporary patterns of care associated with improved survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:11-17.

- Matsuo K, Shimada M, Yamaguchi S, et al. Association of radical hysterectomy surgical volume and survival for early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1086-1098.

- Brennand EA, Quan H. Evaluation of the effect of surgeon’s operative volume and specialty on likelihood of revision after mesh midurethral sling placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1099-1108.

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Outcomes of hysterectomy performed by very low-volume surgeons. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:981-990.

- Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:21282137.

- Wright JD, Ruiz MP, Chen L, et al. Changes in surgical volume and outcomes over time for women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:59-69.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Buskwofie A, et al. Regionalization of care for women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:394-400.

- Fong ZV, Hashimoto DA, Jin G, et al. Simulated volume-based regionalization of complex procedures: impact on spatial access to care. Ann Surg. 2021;274:312-318.

- Knisely A, Huang Y, Melamed A, et al. Effect of regionalization of endometrial cancer care on site of care and patient travel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:58.e1-58.e10.

- Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204-209.

- Shalowitz DI, Nivasch E, Burger RA, et al. Are patients willing to travel for better ovarian cancer care? Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:42-48.

- Rehmani SS, Liu B, Al-Ayoubi AM, et al. Racial disparity in utilization of high-volume hospitals for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:346-353.

- Nattinger AB, Rademacher N, McGinley EL, et al. Can regionalization of care reduce socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival? Med Care. 2021;59:77-81.

- Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J, et al. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:696-704.

- Kurlansky PA, Argenziano M, Dunton R, et al. Quality, not volume, determines outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery in a university-based community hospital network. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:287-293.

- Urbach DR. Pledging to eliminate low-volume surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1388-1390.

- Blanco BA, Kothari AN, Blackwell RH, et al. “Take the Volume Pledge” may result in disparity in access to care. Surgery. 2017;161:837-845.

- Farjah F, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Gaissert H, et al. Volume Pledge is not associated with better short-term outcomes after lung cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3518-3527.

- Tracy EE, Zephyrin LC, Rosman DA, et al. Credentialing based on surgical volume, physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:947-951.

- Statement on credentialing and privileging and volume performance issues. April 1, 2018. American College of Surgeons. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://facs.org/about-acs/statements/credentialing-andprivileging-and-volume-performance-issues/

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Effect of minimum-volume standards on patient outcomes and surgical practice patterns for hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1229-1237.

Over the last 3 decades, abundant evidence has demonstrated the association between surgical volume and outcomes. Patients operated on by high-volume surgeons and at high-volume hospitals have superior outcomes.

Surgical volume in gynecology

The association between both hospital and surgeon volume and outcomes has been explored across a number of gynecologic procedures.3 A meta-analysis that included 741,000 patients found that low-volume surgeons had an increased rate of complications overall, a higher rate of intraoperative complications, and a higher rate of postoperative complications compared with high-volume surgeons. While there was no association between volume and mortality overall, when limited to gynecologic oncology studies, low surgeon volume was associated with increased perioperative mortality.3

While these studies demonstrated a statistically significant association between surgeon volume and perioperative outcomes, the magnitude of the effect is modest compared with other higher-risk procedures associated with greater perioperative morbidity. For example, in a large study that examined oncologic and cardiovascular surgery, perioperative mortality in patients who underwent pancreatic resection was reduced from 15% for low-volume surgeons to 5% for high-volume surgeons.1 By contrast, for gynecologic surgery, complications occurred in 97 per 1,000 patients operated on by high-volume surgeons compared with between 114 and 137 per 1,000 for low-volume surgeons. Thus, to avoid 1 in-hospital complication, 30 surgeries performed by low-volume surgeons would need to be moved to high-volume surgeons. For intraoperative complications, 38 patients would need to be moved from low- to high-volume surgeons to prevent 1 such complication.3 In addition to morbidity and mortality, higher surgeon volume is associated with greater use of minimally invasive surgery, a lower likelihood of conversion to laparotomy, and lower costs.3

Similarly, hospital volume also has been associated with outcomes for gynecologic surgery.4 In a report of patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy, the authors found that the complication rate was 18% lower for patients at high- versus low-volume hospitals. In addition, cost was lower at the high-volume centers.4 Like surgeon volume, the magnitude of the differential in outcomes between high- and low-volume hospitals is often modest.4

While most studies have focused on short-term outcomes, surgical volume appears also to be associated with longer-term outcomes. For gynecologic cancer, studies have demonstrated an association between hospital volume and survival for ovarian and cervical cancer.5-7 A large report of centers across the United States found that the 5-year survival rate increased from 39% for patients treated at low-volume centers to 51% at the highest-volume hospitals.5 In urogynecology, surgeon volume has been associated with midurethral sling revision. One study noted that after an individual surgeon performed 50 procedures a year, each additional case was associated with a decline in the rate of sling revision.8 One could argue that these longer-term end points may be the measures that matter most to patients.

Although the magnitude of the association between surgical volume and outcomes in gynecology appears to be relatively modest, outcomes for very-low-volume (VLV) surgeons are substantially worse. An analysis of more than 430,000 patients who underwent hysterectomy compared outcomes between VLV surgeons (characterized as surgeons who performed only 1 hysterectomy in the prior year) and other gynecologic surgeons. The overall complication rate was 32% in VLV surgeons compared with 10% among other surgeons, while the perioperative mortality rate was 2.5% versus 0.2% in the 2 groups, respectively. Likely reflecting changing practice patterns in gynecology, a sizable number of surgeons were classified as VLV physicians.9

Continue to: Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume...

Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume

The large body of literature on volume and outcomes has led to a number of public health initiatives aimed at reducing perioperative morbidity and mortality. Broadly, these efforts focus on regionalization of care, targeted quality improvement, and the development of minimum volume standards. Each strategy holds promise but also the potential to lead to unwanted consequences.

Regionalization of care

Recognition of the volume-outcomes paradigm has led to efforts to regionalize care for complex procedures to high-volume surgeons and centers.10 A cohort study of surgical patterns of care for Medicare recipients who underwent cancer resections or abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from 1999 to 2008 demonstrated these shifting practice patterns. For example, in 1999–2000, pancreatectomy was performed in 1,308 hospitals, with a median case volume of 5 procedures per year. By 2007–2008, the number of hospitals in which pancreatectomy was performed declined to 978, and the median case volume rose to 16 procedures per year. Importantly, over this time period, risk-adjusted mortality for pancreatectomy declined by 19%, and increased hospital volume was responsible for more than two-thirds of the decline in mortality.10

There has similarly been a gradual concentration of some gynecologic procedures to higher-volume surgeons and centers.11,12 Among patients undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in New York State, 845 surgeons with a mean case volume of 3 procedures per year treated patients in 2000. By 2014, the number of surgeons who performed these operations declined to 317 while mean annual case volume rose to 10 procedures per year. The number of hospitals in which women with endometrial cancer were treated declined from 182 to 98 over the same time period.11 Similar trends were noted for patients undergoing ovarian cancer resection.12 While patterns of gynecologic care for some surgical procedures have clearly changed, it has been more difficult to link these changes to improvements in outcomes.11,12

Despite the intuitive appeal of regionalization of surgical care, such a strategy has a number of limitations and practical challenges. Not surprisingly, limiting the number of surgeons and hospitals that perform a given procedure necessitates that patients travel a greater distance to obtain necessary surgical care.13,14 An analysis of endometrial cancer patients in New York State stratified patients based on their area of residence into 10 hospital referral regions (HRRs), which represent health care markets for tertiary medical care. From 2000 to 2014, the distance patients traveled to receive their surgical care increased in all of the HRRs studied. This was most pronounced in 1 of the HRRs in which the median travel distance rose by 47 miles over the 15-year period (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 2).14

Whether patients are willing to travel for care remains a matter of debate and depends on the disease, the surgical procedure, and the anticipated benefit associated with a longer travel distance.15,16 In a discrete choice experiment, 100 participants were given a hypothetical scenario in which they had potentially resectable pancreatic cancer; they were queried on their willingness to travel for care based on varying differences in mortality between a local and regional hospital.15 When mortality at the local hospital was double that of the regional hospital (6% vs 3%), 45% of patients chose to remain at the local hospital. When the differential increased to a 4 times greater mortality at the local hospital (12% vs 3%), 23% of patients still chose to remain at the local hospital.15

A similar study asked patients with ovarian neoplasms whether they would travel 50 miles to a regional center for surgery based on some degree of increased 5-year survival.16 Overall, 79% of patients would travel for a 4% improvement in survival while 97% would travel for a 12% improvement in survival.16

Lastly, a number of studies have shown that regionalization of surgical care disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients and those with low socioeconomic status.12,13,17 A simulation study on the effect of regionalizing care for pancreatectomy noted that using a hospital volume threshold of 20 procedures per year, a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic patients than White patients would be required to travel to a higher-volume center.13 Similarly, Medicaid recipients were more likely to be affected.13 Despite the inequities in who must travel for regionalized care, prior work has suggested that regionalization of cancer care to high-volume centers may reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival for some cancers.18

Targeted quality improvement

Realizing the practical limitations of regionalization of care, an alternative strategy is to improve the quality of care at low-volume hospitals.5,19 Quality of care and surgical volume often are correlated, and the delivery of high-quality care can mitigate some of the influence of surgical volume on outcomes.

These principles were demonstrated in a study of more than 100,000 patients with ovarian cancer that stratified treating hospitals into volume quintiles.5 As expected, survival (both 2- and 5-year) was highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals (FIGURE 3).5 Similarly, quality of care, measured through adherence to various process measures, was also highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals. Interestingly, in the second-fourth volume quintile hospitals, there was substantial variation in adherence to quality metrics. Among hospitals with higher quality care, an improved survival was noted compared with lower quality care hospitals within the same volume quintile. Survival at high-quality, intermediate-volume hospitals approached that of the high-volume quintile hospitals.5

These findings highlight the importance of quality of care as well as the complex interplay of surgical volume and other factors.20 Many have argued that it may be more appropriate to measure quality of care and past performance and outcomes rather than surgical volume.21

Continue to: Minimum volume standards...

Minimum volume standards

While efforts to regionalize surgical care have gradually evolved, calls have been growing to formalize policies that limit the performance of some procedures to surgeons and centers that meet a minimum volume threshold or standard.21 One such effort, based on consensus from 3 academic hospital systems, was a campaign for hospitals to “Take the Volume Pledge.”21 The campaign’s goal is to encourage health care systems to restrict the performance of 10 procedures to surgeons and hospitals within their systems that meet a minimum volume standard for the given operations.21 In essence, procedures would be restricted for low-volume providers and centers and triaged to higher-volume surgeons and hospitals within a given health care system.21

Proponents of the Volume Pledge argue that it is a relatively straightforward way to align patients and providers to optimize outcomes. The Volume Pledge focuses on larger hospital systems and encourages referral within the given system, thus mitigating competitive and financial concerns about referring patients to outside providers. Those who have argued against the Volume Pledge point out that the volume cut points chosen are somewhat arbitrary, that these policies have the potential to negatively impact rural hospitals and those serving smaller communities, and that quality is a more appropriate metric than volume.22 The Volume Pledge does not include any gynecologic procedures, and to date it has met with only limited success.23

Perhaps more directly applicable to gynecologic surgeons are ongoing national trends to base hospital credentialing on surgical volume. In essence, individual surgeons must demonstrate that they have performed a minimum number of procedures to obtain or retain privileges.24,25 While there is strong evidence of the association between volume and outcomes for some complex surgical procedures, linking volume to credentialing has a number of potential pitfalls. Studies of surgical outcomes based on volume represent average performance, and many low-volume providers have better-than-expected outcomes. Volume measures typically represent recent performance; it is difficult to measure the overall experience of individual surgeons. Similarly, surgical outcomes depend on both the surgeon and the system in which the surgeon operates. It is difficult, if not impossible, to account for differences in the environment in which a surgeon works.25

A study of gynecologic surgeons who performed hysterectomy in New York State demonstrates many of the complexities of volume-based credentialing.26 In a cohort of more than55,000 patients who underwent abdominal hysterectomy, there was a strong association between low surgeon volume and a higher-than-expected rate of complications. If one were to consider limiting privileges to even the lowest-volume providers, there would be a significant impact on the surgical workforce. In this cohort, limiting credentialing to the lowest-volume providers, those who performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year would restrict the privileges of 17.5% of the surgeons in the cohort. Further, in this low-volume cohort that performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year, 69% of the surgeons actually had outcomes that were better than predicted.26 These data highlight not only the difficulty of applying averages to individual surgeons but also the profound impact that policy changes could have on the practice of gynecologic surgery.

Volume-outcomes paradigm discussions continue

The association between higher surgeon and hospital procedural volume for gynecologic surgeries and improved outcomes now has been convincingly demonstrated. With this knowledge, over the last decade the patterns of care for patients undergoing gynecologic surgery have clearly shifted, and these operations are now more commonly being performed by a smaller number of physicians and at fewer hospitals.

While efforts to improve quality are clearly important, many policy interventions, such as regionalization of care, have untoward consequences that must be considered. As we move forward, it will be essential to ensure that there is a robust debate among patients, providers, and policymakers on the merits of public health policies based on the volume-outcomes paradigm. ●

Over the last 3 decades, abundant evidence has demonstrated the association between surgical volume and outcomes. Patients operated on by high-volume surgeons and at high-volume hospitals have superior outcomes.

Surgical volume in gynecology

The association between both hospital and surgeon volume and outcomes has been explored across a number of gynecologic procedures.3 A meta-analysis that included 741,000 patients found that low-volume surgeons had an increased rate of complications overall, a higher rate of intraoperative complications, and a higher rate of postoperative complications compared with high-volume surgeons. While there was no association between volume and mortality overall, when limited to gynecologic oncology studies, low surgeon volume was associated with increased perioperative mortality.3

While these studies demonstrated a statistically significant association between surgeon volume and perioperative outcomes, the magnitude of the effect is modest compared with other higher-risk procedures associated with greater perioperative morbidity. For example, in a large study that examined oncologic and cardiovascular surgery, perioperative mortality in patients who underwent pancreatic resection was reduced from 15% for low-volume surgeons to 5% for high-volume surgeons.1 By contrast, for gynecologic surgery, complications occurred in 97 per 1,000 patients operated on by high-volume surgeons compared with between 114 and 137 per 1,000 for low-volume surgeons. Thus, to avoid 1 in-hospital complication, 30 surgeries performed by low-volume surgeons would need to be moved to high-volume surgeons. For intraoperative complications, 38 patients would need to be moved from low- to high-volume surgeons to prevent 1 such complication.3 In addition to morbidity and mortality, higher surgeon volume is associated with greater use of minimally invasive surgery, a lower likelihood of conversion to laparotomy, and lower costs.3

Similarly, hospital volume also has been associated with outcomes for gynecologic surgery.4 In a report of patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy, the authors found that the complication rate was 18% lower for patients at high- versus low-volume hospitals. In addition, cost was lower at the high-volume centers.4 Like surgeon volume, the magnitude of the differential in outcomes between high- and low-volume hospitals is often modest.4

While most studies have focused on short-term outcomes, surgical volume appears also to be associated with longer-term outcomes. For gynecologic cancer, studies have demonstrated an association between hospital volume and survival for ovarian and cervical cancer.5-7 A large report of centers across the United States found that the 5-year survival rate increased from 39% for patients treated at low-volume centers to 51% at the highest-volume hospitals.5 In urogynecology, surgeon volume has been associated with midurethral sling revision. One study noted that after an individual surgeon performed 50 procedures a year, each additional case was associated with a decline in the rate of sling revision.8 One could argue that these longer-term end points may be the measures that matter most to patients.

Although the magnitude of the association between surgical volume and outcomes in gynecology appears to be relatively modest, outcomes for very-low-volume (VLV) surgeons are substantially worse. An analysis of more than 430,000 patients who underwent hysterectomy compared outcomes between VLV surgeons (characterized as surgeons who performed only 1 hysterectomy in the prior year) and other gynecologic surgeons. The overall complication rate was 32% in VLV surgeons compared with 10% among other surgeons, while the perioperative mortality rate was 2.5% versus 0.2% in the 2 groups, respectively. Likely reflecting changing practice patterns in gynecology, a sizable number of surgeons were classified as VLV physicians.9

Continue to: Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume...

Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume

The large body of literature on volume and outcomes has led to a number of public health initiatives aimed at reducing perioperative morbidity and mortality. Broadly, these efforts focus on regionalization of care, targeted quality improvement, and the development of minimum volume standards. Each strategy holds promise but also the potential to lead to unwanted consequences.

Regionalization of care

Recognition of the volume-outcomes paradigm has led to efforts to regionalize care for complex procedures to high-volume surgeons and centers.10 A cohort study of surgical patterns of care for Medicare recipients who underwent cancer resections or abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from 1999 to 2008 demonstrated these shifting practice patterns. For example, in 1999–2000, pancreatectomy was performed in 1,308 hospitals, with a median case volume of 5 procedures per year. By 2007–2008, the number of hospitals in which pancreatectomy was performed declined to 978, and the median case volume rose to 16 procedures per year. Importantly, over this time period, risk-adjusted mortality for pancreatectomy declined by 19%, and increased hospital volume was responsible for more than two-thirds of the decline in mortality.10

There has similarly been a gradual concentration of some gynecologic procedures to higher-volume surgeons and centers.11,12 Among patients undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in New York State, 845 surgeons with a mean case volume of 3 procedures per year treated patients in 2000. By 2014, the number of surgeons who performed these operations declined to 317 while mean annual case volume rose to 10 procedures per year. The number of hospitals in which women with endometrial cancer were treated declined from 182 to 98 over the same time period.11 Similar trends were noted for patients undergoing ovarian cancer resection.12 While patterns of gynecologic care for some surgical procedures have clearly changed, it has been more difficult to link these changes to improvements in outcomes.11,12

Despite the intuitive appeal of regionalization of surgical care, such a strategy has a number of limitations and practical challenges. Not surprisingly, limiting the number of surgeons and hospitals that perform a given procedure necessitates that patients travel a greater distance to obtain necessary surgical care.13,14 An analysis of endometrial cancer patients in New York State stratified patients based on their area of residence into 10 hospital referral regions (HRRs), which represent health care markets for tertiary medical care. From 2000 to 2014, the distance patients traveled to receive their surgical care increased in all of the HRRs studied. This was most pronounced in 1 of the HRRs in which the median travel distance rose by 47 miles over the 15-year period (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 2).14

Whether patients are willing to travel for care remains a matter of debate and depends on the disease, the surgical procedure, and the anticipated benefit associated with a longer travel distance.15,16 In a discrete choice experiment, 100 participants were given a hypothetical scenario in which they had potentially resectable pancreatic cancer; they were queried on their willingness to travel for care based on varying differences in mortality between a local and regional hospital.15 When mortality at the local hospital was double that of the regional hospital (6% vs 3%), 45% of patients chose to remain at the local hospital. When the differential increased to a 4 times greater mortality at the local hospital (12% vs 3%), 23% of patients still chose to remain at the local hospital.15

A similar study asked patients with ovarian neoplasms whether they would travel 50 miles to a regional center for surgery based on some degree of increased 5-year survival.16 Overall, 79% of patients would travel for a 4% improvement in survival while 97% would travel for a 12% improvement in survival.16

Lastly, a number of studies have shown that regionalization of surgical care disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients and those with low socioeconomic status.12,13,17 A simulation study on the effect of regionalizing care for pancreatectomy noted that using a hospital volume threshold of 20 procedures per year, a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic patients than White patients would be required to travel to a higher-volume center.13 Similarly, Medicaid recipients were more likely to be affected.13 Despite the inequities in who must travel for regionalized care, prior work has suggested that regionalization of cancer care to high-volume centers may reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival for some cancers.18

Targeted quality improvement

Realizing the practical limitations of regionalization of care, an alternative strategy is to improve the quality of care at low-volume hospitals.5,19 Quality of care and surgical volume often are correlated, and the delivery of high-quality care can mitigate some of the influence of surgical volume on outcomes.

These principles were demonstrated in a study of more than 100,000 patients with ovarian cancer that stratified treating hospitals into volume quintiles.5 As expected, survival (both 2- and 5-year) was highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals (FIGURE 3).5 Similarly, quality of care, measured through adherence to various process measures, was also highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals. Interestingly, in the second-fourth volume quintile hospitals, there was substantial variation in adherence to quality metrics. Among hospitals with higher quality care, an improved survival was noted compared with lower quality care hospitals within the same volume quintile. Survival at high-quality, intermediate-volume hospitals approached that of the high-volume quintile hospitals.5

These findings highlight the importance of quality of care as well as the complex interplay of surgical volume and other factors.20 Many have argued that it may be more appropriate to measure quality of care and past performance and outcomes rather than surgical volume.21

Continue to: Minimum volume standards...

Minimum volume standards

While efforts to regionalize surgical care have gradually evolved, calls have been growing to formalize policies that limit the performance of some procedures to surgeons and centers that meet a minimum volume threshold or standard.21 One such effort, based on consensus from 3 academic hospital systems, was a campaign for hospitals to “Take the Volume Pledge.”21 The campaign’s goal is to encourage health care systems to restrict the performance of 10 procedures to surgeons and hospitals within their systems that meet a minimum volume standard for the given operations.21 In essence, procedures would be restricted for low-volume providers and centers and triaged to higher-volume surgeons and hospitals within a given health care system.21

Proponents of the Volume Pledge argue that it is a relatively straightforward way to align patients and providers to optimize outcomes. The Volume Pledge focuses on larger hospital systems and encourages referral within the given system, thus mitigating competitive and financial concerns about referring patients to outside providers. Those who have argued against the Volume Pledge point out that the volume cut points chosen are somewhat arbitrary, that these policies have the potential to negatively impact rural hospitals and those serving smaller communities, and that quality is a more appropriate metric than volume.22 The Volume Pledge does not include any gynecologic procedures, and to date it has met with only limited success.23

Perhaps more directly applicable to gynecologic surgeons are ongoing national trends to base hospital credentialing on surgical volume. In essence, individual surgeons must demonstrate that they have performed a minimum number of procedures to obtain or retain privileges.24,25 While there is strong evidence of the association between volume and outcomes for some complex surgical procedures, linking volume to credentialing has a number of potential pitfalls. Studies of surgical outcomes based on volume represent average performance, and many low-volume providers have better-than-expected outcomes. Volume measures typically represent recent performance; it is difficult to measure the overall experience of individual surgeons. Similarly, surgical outcomes depend on both the surgeon and the system in which the surgeon operates. It is difficult, if not impossible, to account for differences in the environment in which a surgeon works.25

A study of gynecologic surgeons who performed hysterectomy in New York State demonstrates many of the complexities of volume-based credentialing.26 In a cohort of more than55,000 patients who underwent abdominal hysterectomy, there was a strong association between low surgeon volume and a higher-than-expected rate of complications. If one were to consider limiting privileges to even the lowest-volume providers, there would be a significant impact on the surgical workforce. In this cohort, limiting credentialing to the lowest-volume providers, those who performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year would restrict the privileges of 17.5% of the surgeons in the cohort. Further, in this low-volume cohort that performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year, 69% of the surgeons actually had outcomes that were better than predicted.26 These data highlight not only the difficulty of applying averages to individual surgeons but also the profound impact that policy changes could have on the practice of gynecologic surgery.

Volume-outcomes paradigm discussions continue

The association between higher surgeon and hospital procedural volume for gynecologic surgeries and improved outcomes now has been convincingly demonstrated. With this knowledge, over the last decade the patterns of care for patients undergoing gynecologic surgery have clearly shifted, and these operations are now more commonly being performed by a smaller number of physicians and at fewer hospitals.

While efforts to improve quality are clearly important, many policy interventions, such as regionalization of care, have untoward consequences that must be considered. As we move forward, it will be essential to ensure that there is a robust debate among patients, providers, and policymakers on the merits of public health policies based on the volume-outcomes paradigm. ●

- Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117-2127.

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:11281137.

- Mowat A, Maher C, Ballard E. Surgical outcomes for low-volume vs high-volume surgeons in gynecology surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:21-33.

- Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effect of surgical volume on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:709-716.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Association of hospital volume and quality of care with survival for ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:545-553.

- Cliby WA, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Ovarian cancer in the United States: contemporary patterns of care associated with improved survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:11-17.

- Matsuo K, Shimada M, Yamaguchi S, et al. Association of radical hysterectomy surgical volume and survival for early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1086-1098.

- Brennand EA, Quan H. Evaluation of the effect of surgeon’s operative volume and specialty on likelihood of revision after mesh midurethral sling placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1099-1108.

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Outcomes of hysterectomy performed by very low-volume surgeons. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:981-990.

- Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:21282137.

- Wright JD, Ruiz MP, Chen L, et al. Changes in surgical volume and outcomes over time for women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:59-69.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Buskwofie A, et al. Regionalization of care for women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:394-400.

- Fong ZV, Hashimoto DA, Jin G, et al. Simulated volume-based regionalization of complex procedures: impact on spatial access to care. Ann Surg. 2021;274:312-318.

- Knisely A, Huang Y, Melamed A, et al. Effect of regionalization of endometrial cancer care on site of care and patient travel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:58.e1-58.e10.

- Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204-209.

- Shalowitz DI, Nivasch E, Burger RA, et al. Are patients willing to travel for better ovarian cancer care? Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:42-48.

- Rehmani SS, Liu B, Al-Ayoubi AM, et al. Racial disparity in utilization of high-volume hospitals for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:346-353.

- Nattinger AB, Rademacher N, McGinley EL, et al. Can regionalization of care reduce socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival? Med Care. 2021;59:77-81.

- Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J, et al. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:696-704.

- Kurlansky PA, Argenziano M, Dunton R, et al. Quality, not volume, determines outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery in a university-based community hospital network. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:287-293.

- Urbach DR. Pledging to eliminate low-volume surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1388-1390.

- Blanco BA, Kothari AN, Blackwell RH, et al. “Take the Volume Pledge” may result in disparity in access to care. Surgery. 2017;161:837-845.

- Farjah F, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Gaissert H, et al. Volume Pledge is not associated with better short-term outcomes after lung cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3518-3527.

- Tracy EE, Zephyrin LC, Rosman DA, et al. Credentialing based on surgical volume, physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:947-951.

- Statement on credentialing and privileging and volume performance issues. April 1, 2018. American College of Surgeons. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://facs.org/about-acs/statements/credentialing-andprivileging-and-volume-performance-issues/

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Effect of minimum-volume standards on patient outcomes and surgical practice patterns for hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1229-1237.

- Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117-2127.

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:11281137.

- Mowat A, Maher C, Ballard E. Surgical outcomes for low-volume vs high-volume surgeons in gynecology surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:21-33.

- Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effect of surgical volume on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:709-716.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Association of hospital volume and quality of care with survival for ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:545-553.

- Cliby WA, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Ovarian cancer in the United States: contemporary patterns of care associated with improved survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:11-17.

- Matsuo K, Shimada M, Yamaguchi S, et al. Association of radical hysterectomy surgical volume and survival for early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1086-1098.

- Brennand EA, Quan H. Evaluation of the effect of surgeon’s operative volume and specialty on likelihood of revision after mesh midurethral sling placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1099-1108.

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Outcomes of hysterectomy performed by very low-volume surgeons. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:981-990.

- Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:21282137.

- Wright JD, Ruiz MP, Chen L, et al. Changes in surgical volume and outcomes over time for women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:59-69.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Buskwofie A, et al. Regionalization of care for women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:394-400.

- Fong ZV, Hashimoto DA, Jin G, et al. Simulated volume-based regionalization of complex procedures: impact on spatial access to care. Ann Surg. 2021;274:312-318.

- Knisely A, Huang Y, Melamed A, et al. Effect of regionalization of endometrial cancer care on site of care and patient travel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:58.e1-58.e10.

- Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204-209.

- Shalowitz DI, Nivasch E, Burger RA, et al. Are patients willing to travel for better ovarian cancer care? Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:42-48.

- Rehmani SS, Liu B, Al-Ayoubi AM, et al. Racial disparity in utilization of high-volume hospitals for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:346-353.

- Nattinger AB, Rademacher N, McGinley EL, et al. Can regionalization of care reduce socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival? Med Care. 2021;59:77-81.

- Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J, et al. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:696-704.

- Kurlansky PA, Argenziano M, Dunton R, et al. Quality, not volume, determines outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery in a university-based community hospital network. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:287-293.

- Urbach DR. Pledging to eliminate low-volume surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1388-1390.

- Blanco BA, Kothari AN, Blackwell RH, et al. “Take the Volume Pledge” may result in disparity in access to care. Surgery. 2017;161:837-845.

- Farjah F, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Gaissert H, et al. Volume Pledge is not associated with better short-term outcomes after lung cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3518-3527.

- Tracy EE, Zephyrin LC, Rosman DA, et al. Credentialing based on surgical volume, physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:947-951.

- Statement on credentialing and privileging and volume performance issues. April 1, 2018. American College of Surgeons. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://facs.org/about-acs/statements/credentialing-andprivileging-and-volume-performance-issues/

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Effect of minimum-volume standards on patient outcomes and surgical practice patterns for hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1229-1237.