User login

A 15-year-old girl presents to your clinic with poorly controlled chronic migraines that prevent her from attending school three to four days per month. As part of her treatment regimen, you are considering migraine prevention strategies. Should you prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate?

Migraine headaches are the most common reason for headache presentation in pediatric neurology outpatient clinics, affecting 5% to 10% of the pediatric population worldwide.2 Current recommendations regarding prophylactic migraine therapy in childhood are based on consensus opinions.3,4 While the FDA has not approved any medications for migraine prevention in children younger than 12, surveys of pediatric headache specialists suggest that amitriptyline and topiramate are among the most commonly prescribed medications for childhood migraine prophylaxis.3,4

There is low-quality evidence from individual RCTs about the effectiveness of topiramate. A meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues included three RCTs comparing topiramate to placebo for the prevention of episodic migraines (migraine headaches that occur < 15 x/mo) in a combined total of 283 children younger than 18.5 Topiramate demonstrated a nonclinically significant, but statistically significant, reduction of less than one headache per month (–0.71). This is based on moderate-quality evidence due to a high placebo response rate and study durations of only 12 weeks.5 The FDA has approved topiramate for migraine prevention in children ages 12 to 17.6

Adult guidelines. The findings described above are consistent with the most recent adult guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.7 In a joint publication from 2012, these societies recommended both topiramate and amitriptyline for the prevention of migraines in adults based on high-quality (Level A) and medium-quality (Level B) evidence, respectively.7

STUDY SUMMARY

No better than placebo in children

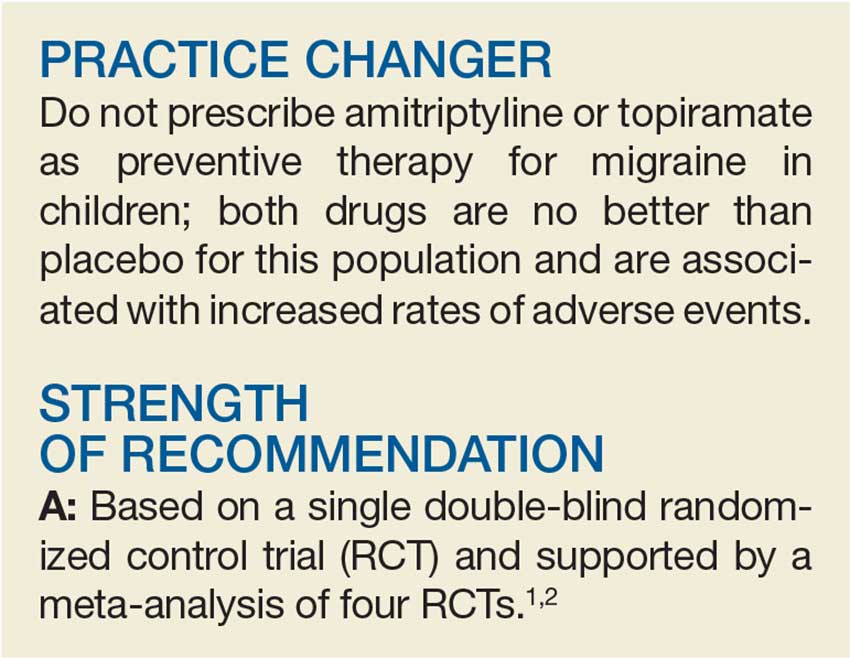

A multicenter, double-blind RCT by Powers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of pediatric migraines.1 Target dosing for amitriptyline and topiramate was set at 1 mg/kg/d and 2 mg/kg/d, respectively. Titration toward these doses occurred over an eight-week period, based on reported adverse effects. Patients then continued their maximum tolerated dose for an additional 16 weeks.

Patients were predominantly white (70%), female (68%), and 8 to 17 years of age. They had at least four headache days over a prospective 28-day pretreatment period and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) score of 11 to 139 (scores of 11-50 indicate mild-to-moderate disability; of > 50, severe disability).1,8 The primary endpoint consisted of at least a 50% relative reduction (RR) in the number of headache days in the final 28 days of the trial, compared to the 28-day pretherapy (baseline) period.1

The authors of the study included 328 patients in the primary efficacy analysis and randomly assigned them in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either amitriptyline (132 patients), topiramate (130 patients), or placebo (66 patients). After 24 weeks of therapy, there was no significant difference between the amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo groups in the primary endpoint (52% amitriptyline, 55% topiramate, 61% placebo; adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.71 between amitriptyline and placebo; OR, 0.81 between topiramate and placebo; OR, 0.88 between amitriptyline and topiramate).

Continue to: There was also no difference...

There was also no difference in the secondary outcomes of absolute reduction in headache days and headache-related disability as determined by PedMIDAS. The study was stopped early for futility. Compared with placebo, amitriptyline significantly increased fatigue (number needed to harm [NNH], 8) and dry mouth (NNH, 9) and was associated with three serious adverse events of altered mood. Compared with placebo, topiramate significantly increased paresthesia (NNH, 4) and weight loss (NNH, 13) and was associated with one serious adverse event—a suicide attempt.1

WHAT’S NEW?

Higher-level evidence, lack of efficacy

This RCT provides new, higher-level evidence that demonstrates the lack of efficacy of amitriptyline and topiramate in the prevention of pediatric migraines. It also highlights the risk for increased adverse events with topiramate and amitriptyline.

Two of the three topiramate trials used in the older meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues and this new RCT were included in an updated meta-analysis by Le and colleagues (total participants, 465) published in 2017.1,2,5 This newer meta-analysis found no statistical benefit associated with the use of topiramate over placebo. It demonstrated a nonsignificant decrease in the number of patients with at least a 50% relative reduction in headache frequency (risk ratio, 1.26) and in the overall number of headache days (mean difference, –0.77) in patients younger than 18.2 Both meta-analyses, however, showed an increase in the rate of adverse events in patients using topiramate versus placebo.2,5

CAVEATS

Is there a gender predominance?

El-Chammas and colleagues describe male pediatric patients as being the predominant pediatric gender with migraines.5 However, they do not quote an incidence rate or cite the reference for this statement. No other reference to gender predominance was noted in the literature. The current study, in addition to the total population of the meta-analysis by Le and colleagues, included women as the predominant patient population.1,2 Hopefully, future studies will help to delineate whether there is a gender predominance and, if so, whether the current treatment data apply to both genders.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

There are no barriers to implementing this recommendation immediately.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018;67 [4]:238-239, 241).

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

4. Hershey AD. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:190-204.

5. El-Chammas K, Keyes J, Thompson N, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:250-258.

6. Qudexy XR. Highlights of prescribing information. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205122s003s005lbl.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2018.

7. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

8. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.

A 15-year-old girl presents to your clinic with poorly controlled chronic migraines that prevent her from attending school three to four days per month. As part of her treatment regimen, you are considering migraine prevention strategies. Should you prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate?

Migraine headaches are the most common reason for headache presentation in pediatric neurology outpatient clinics, affecting 5% to 10% of the pediatric population worldwide.2 Current recommendations regarding prophylactic migraine therapy in childhood are based on consensus opinions.3,4 While the FDA has not approved any medications for migraine prevention in children younger than 12, surveys of pediatric headache specialists suggest that amitriptyline and topiramate are among the most commonly prescribed medications for childhood migraine prophylaxis.3,4

There is low-quality evidence from individual RCTs about the effectiveness of topiramate. A meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues included three RCTs comparing topiramate to placebo for the prevention of episodic migraines (migraine headaches that occur < 15 x/mo) in a combined total of 283 children younger than 18.5 Topiramate demonstrated a nonclinically significant, but statistically significant, reduction of less than one headache per month (–0.71). This is based on moderate-quality evidence due to a high placebo response rate and study durations of only 12 weeks.5 The FDA has approved topiramate for migraine prevention in children ages 12 to 17.6

Adult guidelines. The findings described above are consistent with the most recent adult guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.7 In a joint publication from 2012, these societies recommended both topiramate and amitriptyline for the prevention of migraines in adults based on high-quality (Level A) and medium-quality (Level B) evidence, respectively.7

STUDY SUMMARY

No better than placebo in children

A multicenter, double-blind RCT by Powers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of pediatric migraines.1 Target dosing for amitriptyline and topiramate was set at 1 mg/kg/d and 2 mg/kg/d, respectively. Titration toward these doses occurred over an eight-week period, based on reported adverse effects. Patients then continued their maximum tolerated dose for an additional 16 weeks.

Patients were predominantly white (70%), female (68%), and 8 to 17 years of age. They had at least four headache days over a prospective 28-day pretreatment period and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) score of 11 to 139 (scores of 11-50 indicate mild-to-moderate disability; of > 50, severe disability).1,8 The primary endpoint consisted of at least a 50% relative reduction (RR) in the number of headache days in the final 28 days of the trial, compared to the 28-day pretherapy (baseline) period.1

The authors of the study included 328 patients in the primary efficacy analysis and randomly assigned them in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either amitriptyline (132 patients), topiramate (130 patients), or placebo (66 patients). After 24 weeks of therapy, there was no significant difference between the amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo groups in the primary endpoint (52% amitriptyline, 55% topiramate, 61% placebo; adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.71 between amitriptyline and placebo; OR, 0.81 between topiramate and placebo; OR, 0.88 between amitriptyline and topiramate).

Continue to: There was also no difference...

There was also no difference in the secondary outcomes of absolute reduction in headache days and headache-related disability as determined by PedMIDAS. The study was stopped early for futility. Compared with placebo, amitriptyline significantly increased fatigue (number needed to harm [NNH], 8) and dry mouth (NNH, 9) and was associated with three serious adverse events of altered mood. Compared with placebo, topiramate significantly increased paresthesia (NNH, 4) and weight loss (NNH, 13) and was associated with one serious adverse event—a suicide attempt.1

WHAT’S NEW?

Higher-level evidence, lack of efficacy

This RCT provides new, higher-level evidence that demonstrates the lack of efficacy of amitriptyline and topiramate in the prevention of pediatric migraines. It also highlights the risk for increased adverse events with topiramate and amitriptyline.

Two of the three topiramate trials used in the older meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues and this new RCT were included in an updated meta-analysis by Le and colleagues (total participants, 465) published in 2017.1,2,5 This newer meta-analysis found no statistical benefit associated with the use of topiramate over placebo. It demonstrated a nonsignificant decrease in the number of patients with at least a 50% relative reduction in headache frequency (risk ratio, 1.26) and in the overall number of headache days (mean difference, –0.77) in patients younger than 18.2 Both meta-analyses, however, showed an increase in the rate of adverse events in patients using topiramate versus placebo.2,5

CAVEATS

Is there a gender predominance?

El-Chammas and colleagues describe male pediatric patients as being the predominant pediatric gender with migraines.5 However, they do not quote an incidence rate or cite the reference for this statement. No other reference to gender predominance was noted in the literature. The current study, in addition to the total population of the meta-analysis by Le and colleagues, included women as the predominant patient population.1,2 Hopefully, future studies will help to delineate whether there is a gender predominance and, if so, whether the current treatment data apply to both genders.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

There are no barriers to implementing this recommendation immediately.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018;67 [4]:238-239, 241).

A 15-year-old girl presents to your clinic with poorly controlled chronic migraines that prevent her from attending school three to four days per month. As part of her treatment regimen, you are considering migraine prevention strategies. Should you prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate?

Migraine headaches are the most common reason for headache presentation in pediatric neurology outpatient clinics, affecting 5% to 10% of the pediatric population worldwide.2 Current recommendations regarding prophylactic migraine therapy in childhood are based on consensus opinions.3,4 While the FDA has not approved any medications for migraine prevention in children younger than 12, surveys of pediatric headache specialists suggest that amitriptyline and topiramate are among the most commonly prescribed medications for childhood migraine prophylaxis.3,4

There is low-quality evidence from individual RCTs about the effectiveness of topiramate. A meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues included three RCTs comparing topiramate to placebo for the prevention of episodic migraines (migraine headaches that occur < 15 x/mo) in a combined total of 283 children younger than 18.5 Topiramate demonstrated a nonclinically significant, but statistically significant, reduction of less than one headache per month (–0.71). This is based on moderate-quality evidence due to a high placebo response rate and study durations of only 12 weeks.5 The FDA has approved topiramate for migraine prevention in children ages 12 to 17.6

Adult guidelines. The findings described above are consistent with the most recent adult guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.7 In a joint publication from 2012, these societies recommended both topiramate and amitriptyline for the prevention of migraines in adults based on high-quality (Level A) and medium-quality (Level B) evidence, respectively.7

STUDY SUMMARY

No better than placebo in children

A multicenter, double-blind RCT by Powers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of pediatric migraines.1 Target dosing for amitriptyline and topiramate was set at 1 mg/kg/d and 2 mg/kg/d, respectively. Titration toward these doses occurred over an eight-week period, based on reported adverse effects. Patients then continued their maximum tolerated dose for an additional 16 weeks.

Patients were predominantly white (70%), female (68%), and 8 to 17 years of age. They had at least four headache days over a prospective 28-day pretreatment period and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) score of 11 to 139 (scores of 11-50 indicate mild-to-moderate disability; of > 50, severe disability).1,8 The primary endpoint consisted of at least a 50% relative reduction (RR) in the number of headache days in the final 28 days of the trial, compared to the 28-day pretherapy (baseline) period.1

The authors of the study included 328 patients in the primary efficacy analysis and randomly assigned them in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either amitriptyline (132 patients), topiramate (130 patients), or placebo (66 patients). After 24 weeks of therapy, there was no significant difference between the amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo groups in the primary endpoint (52% amitriptyline, 55% topiramate, 61% placebo; adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.71 between amitriptyline and placebo; OR, 0.81 between topiramate and placebo; OR, 0.88 between amitriptyline and topiramate).

Continue to: There was also no difference...

There was also no difference in the secondary outcomes of absolute reduction in headache days and headache-related disability as determined by PedMIDAS. The study was stopped early for futility. Compared with placebo, amitriptyline significantly increased fatigue (number needed to harm [NNH], 8) and dry mouth (NNH, 9) and was associated with three serious adverse events of altered mood. Compared with placebo, topiramate significantly increased paresthesia (NNH, 4) and weight loss (NNH, 13) and was associated with one serious adverse event—a suicide attempt.1

WHAT’S NEW?

Higher-level evidence, lack of efficacy

This RCT provides new, higher-level evidence that demonstrates the lack of efficacy of amitriptyline and topiramate in the prevention of pediatric migraines. It also highlights the risk for increased adverse events with topiramate and amitriptyline.

Two of the three topiramate trials used in the older meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues and this new RCT were included in an updated meta-analysis by Le and colleagues (total participants, 465) published in 2017.1,2,5 This newer meta-analysis found no statistical benefit associated with the use of topiramate over placebo. It demonstrated a nonsignificant decrease in the number of patients with at least a 50% relative reduction in headache frequency (risk ratio, 1.26) and in the overall number of headache days (mean difference, –0.77) in patients younger than 18.2 Both meta-analyses, however, showed an increase in the rate of adverse events in patients using topiramate versus placebo.2,5

CAVEATS

Is there a gender predominance?

El-Chammas and colleagues describe male pediatric patients as being the predominant pediatric gender with migraines.5 However, they do not quote an incidence rate or cite the reference for this statement. No other reference to gender predominance was noted in the literature. The current study, in addition to the total population of the meta-analysis by Le and colleagues, included women as the predominant patient population.1,2 Hopefully, future studies will help to delineate whether there is a gender predominance and, if so, whether the current treatment data apply to both genders.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

There are no barriers to implementing this recommendation immediately.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018;67 [4]:238-239, 241).

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

4. Hershey AD. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:190-204.

5. El-Chammas K, Keyes J, Thompson N, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:250-258.

6. Qudexy XR. Highlights of prescribing information. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205122s003s005lbl.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2018.

7. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

8. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

4. Hershey AD. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:190-204.

5. El-Chammas K, Keyes J, Thompson N, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:250-258.

6. Qudexy XR. Highlights of prescribing information. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205122s003s005lbl.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2018.

7. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

8. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.