User login

In the 1970s and 1980s, indigent patients experienced problems at hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) around the country. They were refused care and shuttled to other facilities for services. To protect patients against these types of abuses, Congress passed The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA).·

EMTALA mandates that all patients presenting to the ED - regardless of insurance status - receive a medical screening examination and be medically stable prior to transfer to another facility. If a hospital has the facilities to treat the emergency, the patient can not be transferred to another ED. To address these requirements, every hospital must have physicians on call to assist emergency physicians in assessing and treating unassigned patients.

By the late 1990s, as EMTALA requirements took hold, inadequate on-call physician coverage reached crisis proportions and became a front page issue. In 1999, USA Today carried the following headline: "A Care Crisis in ERs: Nation's Hospitals Plagued by Shortage of On-Call Specialists" (1). In that same year, Modem Healthcare ran an article with the following headline: "Blaming the Docs: Patient Dumping Probes See Physicians as Culprits in Turning Away Indigent from ERs" (2). In California, a task force was formed to address the matter (3), and the American Medical Association (AMA) began exploring solutions at the highest levels (4).

Why do hospitals have problems organizing their medical staff to be available to provide on-call treatment of unassigned patients in the ED and subsequent to admission? There appear to be three major reasons for this problem.

First, at a minimum, on-call treatment of unassigned patients creates an inconvenience for physicians, taking away from their personal time; worse. it can reduce the number of available hours they have to spend with their office-based patients.

Second, there are financial disincentives to on-call coverage. Often unassigned patients presenting in the ED are uninsured or under-insured. On-call physicians frequently do not receive adequate compensation for the task of treating these patients.

Finally, on-call duty can bring bureaucratic hassles and/or legal liability for physicians. Dealing with state Medicaid agencies may require addressing administrative requirements, completing paperwork, and paying penalties for not following the rules.

Richard Frankenstein, MD, a pulmonologist in Southern California, admitted an uninsured patient with multiple chronic illnesses when he was the on-call physician at one of his affiliated hospitals. The patient spent 8 weeks in the hospital, much of that time in intensive care. Frankenstein often visited this patient twice a day, so his already busy schedule began hour earlier and ended 1 hour later. He received no compensation for these efforts. That commitment dragged me away from my primary responsibilities,” said Frankenstein. "I'm no longer on staff there, and that situation was a major reason that I resigned (5).

During the past 5 years, the crisis of on-call physician coverage has been significantly reduced and hospitalists emerge as one of the major reasons why. Although there are still issues related to the availability of on-call specialists and surgeons, hospitals that have implemented hospital medicine programs are able to make available experienced general internists to triage, admit, and treat unassigned patients.

Hospital Medicine Programs:

A Value Added Resource to Hospitals

Hospital medicine programs are characterized by several unique features that facilitate the treatment of unassigned patients and result in significant benefits for hospitals. Figure 1 above illustrates these relationships.

Mark Aronson, MD, serves as a member of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), a 5O0-bed academic medical center in Boston and is also Vice Chairman for Quality and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. BIDMC has a mature hospital medicine program, and approximately 55-60% of the program's patients are unassigned, representing more than 25% of the hospital's general medicine census. Aronson believes that the hospital medicine program provides value to both patients and the institution. He described a case in which a nursing home patient without health insurance presented in the ED. After the initial evaluation, the ED attending decided to admit the patient. One of the hospitalists recognized the patient as someone he had treated several times before. He knew that her medical condition would not require hospitalization and arranged the appropriate treatment, allowing for transfer back to the nursing home. “In this situation, because the hospitalist had a relationship and history with the unassigned patient, the patient received timely, quality medical care and the hospital saved a significant amount of money” (5).

In the ED, the prompt and efficient treatment of unassigned patients can reduce backlogs and minimize hassles for emergency physicians. There is no need for the emergency physician to track down an on-call physician to admit the patient. The ED maintains a better work flow and makes better use of their resources, especially of physician and nursing time as well as space. Most hospitalists are familiar with pertinent laws (e.g., EMTALA) and insurance company policies, thereby spending less time investigating and resolving problems. The hospitals benefits through improved throughput.

"We have a high-volume ED with a large percentage of unassigned patients. In addition our hospital census is often 120% at midday and 90% at midnight. Efficient flow of patients though the ED at all hours is a critical issue at our hospital," says Patrick Cawley, MD, Director of Hospitalist Services at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. "We have been asked to lead throughput initiatives which have resulted in a dramatic reduction in backlogs and the movement of patients out of the ED either to a bed or possibly to an alternative setting.”

The members of the medical staff of a hospital are often the driving force for the creation of a hospital medicine program. Having hopitalists at their institution may mean that affiliated physicians do not have to assume the undesirable responsibilities of participating in an on-call schedule. Furthermore, since hospitalists typically do not have an office practice, community physicians still have the opportunity to care for the unassigned patients once they are discharged, thereby building their practice. Hospitals can refer the patients according to an equitable schedule approved by the medical staff. By addressing issues related to on-call physician coverage, a hospital can improve medical staff relations.

At Winchester Medical Center in Virginia, family practitioners in the area surrendered their admitting privileges, creating an onerous call schedule for generalist internists. The hospital hired four hospitalists to admit and treat all unassigned patients. Instead of taking call, the internists are part of a primary care roster and rotate responsibility for unassigned patients once they are discharged (6). It has been a win-win solution for the hospital and the medical staff.

Often the unassigned patients have significant discharge planning and placement problems, especially those that are uninsured. While these issues can be daunting to the office-based physicians, hospitalists usually have a more comprehensive knowledge of the resources of the hospital and the community to help solve these placement and post-discharge care issues.

In treating unassigned patients, hospitalists blend their clinical skills with knowledge of their hospital’s objectives, concerns, policies, and procedures. Since they are a relatively small, cohesive group within the institution, hospitalists are often familiar with practice guidelines, medical records documentation requirements, computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems, quality initiatives, and utilization management requirements.

"The hospitalists’ responsibilities in our program must have a good citizenship component," says Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, Director of the Inpatient Medicine Service at Merry Medical Center in Springfield, MA and co-founder of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). "Each physician must serve on a committee, a project, or a program that serves the hospital. Hospitalists are often the leaders of hospital-wide initiatives directed at quality of care, utilization management, and throughput.”

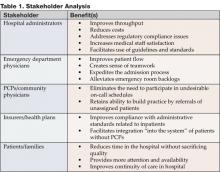

Stakeholder Analysis

By treating unassigned patients, hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. The benefits to these stakeholders are summarized in Table 1.

Assigning Value to Hospitalists' Work

Hospitalists typically manage unassigned and uninsured patients as part of their regular job duties. It is important that the administrator or leader of the hospital medicine group have a budgetary understanding of how to "score" the services that the hospitalists provide to these patients.

If the hospitalist service is provided by an independent, contracted group, they may be paid for treating the unassigned, uninsured patients. Often the payment is in the form of a case rate, based on the "average" number of services provided in an admission and using a Medicare or other mutually agreed upon fee schedule.

If the hospitalists are employees of the hospital, it is expected that they will assume responsibility for unassigned, uninsured patients. Although the hospital medicine group will not receive direct reimbursement for seeing these patients (unlike a contracted hospitalist group), the value of this service to the hospital must be recognized. In these situations, hospital administrators should acknowledge the critical need to credit the hospitalists for real work that must be performed but that generates little or no revenue. An equivalent case rate can be credited as a paper transaction to the hospitalist group to address the value of these services.

Conclusion

Given the current economic environment, the issue of treating unassigned and uninsured patients will not soon diminish. Demand is likely to increase with the nationwide growth in the number of uninsured patients. Physician resistance to call coverage and the rise of malpractice premiums will continue to create more pressure for hospitals to find solutions to this crisis. "We recognize that hospitalists are only part of the solution," says Ron Angus, MS, Past President of SHM. "Hospitals and government agencies must provide funding to cover the costs of inpatient care for acutely ill, uninsured - and usually unassigned - patients. Hospitals must also find ways to ensure that other specialists are available to hospitalists for acutely ill inpatients who require specialty expertise or procedures. With such cooperation and participation, hospitalists can be an important part of the solution to the problems now reaching crisis proportions in American emergency rooms" (7).

References

- Appleby J. Hospitals plagued by on-call shortage. USA Today June 16. 1999.

- Blaming the docs: patient dumping probes see physicians as culprits in turning away indigent from ERs. Modern Healthcare August 9, 1999.

- Winston K, The Advisory Board Company, Clinical Initiatives Center. Cause for concern: ensuring adequate and timely on-call physician coverage in the emergency department. ED Watch Issue #4, May 2, 2000.

- Foubister V. Is there a dearth of specialists in the ED? American Medical News July 12, 1999.

- Wanted: doctors willing to take ER call. ACP-ASIM Observer American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, November 2001.

- Aronson M, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Personal interview. December 2004.

- Angus R, letter to the editor, ACP-ASIM Observer American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, December 2001.

In the 1970s and 1980s, indigent patients experienced problems at hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) around the country. They were refused care and shuttled to other facilities for services. To protect patients against these types of abuses, Congress passed The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA).·

EMTALA mandates that all patients presenting to the ED - regardless of insurance status - receive a medical screening examination and be medically stable prior to transfer to another facility. If a hospital has the facilities to treat the emergency, the patient can not be transferred to another ED. To address these requirements, every hospital must have physicians on call to assist emergency physicians in assessing and treating unassigned patients.

By the late 1990s, as EMTALA requirements took hold, inadequate on-call physician coverage reached crisis proportions and became a front page issue. In 1999, USA Today carried the following headline: "A Care Crisis in ERs: Nation's Hospitals Plagued by Shortage of On-Call Specialists" (1). In that same year, Modem Healthcare ran an article with the following headline: "Blaming the Docs: Patient Dumping Probes See Physicians as Culprits in Turning Away Indigent from ERs" (2). In California, a task force was formed to address the matter (3), and the American Medical Association (AMA) began exploring solutions at the highest levels (4).

Why do hospitals have problems organizing their medical staff to be available to provide on-call treatment of unassigned patients in the ED and subsequent to admission? There appear to be three major reasons for this problem.

First, at a minimum, on-call treatment of unassigned patients creates an inconvenience for physicians, taking away from their personal time; worse. it can reduce the number of available hours they have to spend with their office-based patients.

Second, there are financial disincentives to on-call coverage. Often unassigned patients presenting in the ED are uninsured or under-insured. On-call physicians frequently do not receive adequate compensation for the task of treating these patients.

Finally, on-call duty can bring bureaucratic hassles and/or legal liability for physicians. Dealing with state Medicaid agencies may require addressing administrative requirements, completing paperwork, and paying penalties for not following the rules.

Richard Frankenstein, MD, a pulmonologist in Southern California, admitted an uninsured patient with multiple chronic illnesses when he was the on-call physician at one of his affiliated hospitals. The patient spent 8 weeks in the hospital, much of that time in intensive care. Frankenstein often visited this patient twice a day, so his already busy schedule began hour earlier and ended 1 hour later. He received no compensation for these efforts. That commitment dragged me away from my primary responsibilities,” said Frankenstein. "I'm no longer on staff there, and that situation was a major reason that I resigned (5).

During the past 5 years, the crisis of on-call physician coverage has been significantly reduced and hospitalists emerge as one of the major reasons why. Although there are still issues related to the availability of on-call specialists and surgeons, hospitals that have implemented hospital medicine programs are able to make available experienced general internists to triage, admit, and treat unassigned patients.

Hospital Medicine Programs:

A Value Added Resource to Hospitals

Hospital medicine programs are characterized by several unique features that facilitate the treatment of unassigned patients and result in significant benefits for hospitals. Figure 1 above illustrates these relationships.

Mark Aronson, MD, serves as a member of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), a 5O0-bed academic medical center in Boston and is also Vice Chairman for Quality and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. BIDMC has a mature hospital medicine program, and approximately 55-60% of the program's patients are unassigned, representing more than 25% of the hospital's general medicine census. Aronson believes that the hospital medicine program provides value to both patients and the institution. He described a case in which a nursing home patient without health insurance presented in the ED. After the initial evaluation, the ED attending decided to admit the patient. One of the hospitalists recognized the patient as someone he had treated several times before. He knew that her medical condition would not require hospitalization and arranged the appropriate treatment, allowing for transfer back to the nursing home. “In this situation, because the hospitalist had a relationship and history with the unassigned patient, the patient received timely, quality medical care and the hospital saved a significant amount of money” (5).

In the ED, the prompt and efficient treatment of unassigned patients can reduce backlogs and minimize hassles for emergency physicians. There is no need for the emergency physician to track down an on-call physician to admit the patient. The ED maintains a better work flow and makes better use of their resources, especially of physician and nursing time as well as space. Most hospitalists are familiar with pertinent laws (e.g., EMTALA) and insurance company policies, thereby spending less time investigating and resolving problems. The hospitals benefits through improved throughput.

"We have a high-volume ED with a large percentage of unassigned patients. In addition our hospital census is often 120% at midday and 90% at midnight. Efficient flow of patients though the ED at all hours is a critical issue at our hospital," says Patrick Cawley, MD, Director of Hospitalist Services at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. "We have been asked to lead throughput initiatives which have resulted in a dramatic reduction in backlogs and the movement of patients out of the ED either to a bed or possibly to an alternative setting.”

The members of the medical staff of a hospital are often the driving force for the creation of a hospital medicine program. Having hopitalists at their institution may mean that affiliated physicians do not have to assume the undesirable responsibilities of participating in an on-call schedule. Furthermore, since hospitalists typically do not have an office practice, community physicians still have the opportunity to care for the unassigned patients once they are discharged, thereby building their practice. Hospitals can refer the patients according to an equitable schedule approved by the medical staff. By addressing issues related to on-call physician coverage, a hospital can improve medical staff relations.

At Winchester Medical Center in Virginia, family practitioners in the area surrendered their admitting privileges, creating an onerous call schedule for generalist internists. The hospital hired four hospitalists to admit and treat all unassigned patients. Instead of taking call, the internists are part of a primary care roster and rotate responsibility for unassigned patients once they are discharged (6). It has been a win-win solution for the hospital and the medical staff.

Often the unassigned patients have significant discharge planning and placement problems, especially those that are uninsured. While these issues can be daunting to the office-based physicians, hospitalists usually have a more comprehensive knowledge of the resources of the hospital and the community to help solve these placement and post-discharge care issues.

In treating unassigned patients, hospitalists blend their clinical skills with knowledge of their hospital’s objectives, concerns, policies, and procedures. Since they are a relatively small, cohesive group within the institution, hospitalists are often familiar with practice guidelines, medical records documentation requirements, computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems, quality initiatives, and utilization management requirements.

"The hospitalists’ responsibilities in our program must have a good citizenship component," says Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, Director of the Inpatient Medicine Service at Merry Medical Center in Springfield, MA and co-founder of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). "Each physician must serve on a committee, a project, or a program that serves the hospital. Hospitalists are often the leaders of hospital-wide initiatives directed at quality of care, utilization management, and throughput.”

Stakeholder Analysis

By treating unassigned patients, hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. The benefits to these stakeholders are summarized in Table 1.

Assigning Value to Hospitalists' Work

Hospitalists typically manage unassigned and uninsured patients as part of their regular job duties. It is important that the administrator or leader of the hospital medicine group have a budgetary understanding of how to "score" the services that the hospitalists provide to these patients.

If the hospitalist service is provided by an independent, contracted group, they may be paid for treating the unassigned, uninsured patients. Often the payment is in the form of a case rate, based on the "average" number of services provided in an admission and using a Medicare or other mutually agreed upon fee schedule.

If the hospitalists are employees of the hospital, it is expected that they will assume responsibility for unassigned, uninsured patients. Although the hospital medicine group will not receive direct reimbursement for seeing these patients (unlike a contracted hospitalist group), the value of this service to the hospital must be recognized. In these situations, hospital administrators should acknowledge the critical need to credit the hospitalists for real work that must be performed but that generates little or no revenue. An equivalent case rate can be credited as a paper transaction to the hospitalist group to address the value of these services.

Conclusion

Given the current economic environment, the issue of treating unassigned and uninsured patients will not soon diminish. Demand is likely to increase with the nationwide growth in the number of uninsured patients. Physician resistance to call coverage and the rise of malpractice premiums will continue to create more pressure for hospitals to find solutions to this crisis. "We recognize that hospitalists are only part of the solution," says Ron Angus, MS, Past President of SHM. "Hospitals and government agencies must provide funding to cover the costs of inpatient care for acutely ill, uninsured - and usually unassigned - patients. Hospitals must also find ways to ensure that other specialists are available to hospitalists for acutely ill inpatients who require specialty expertise or procedures. With such cooperation and participation, hospitalists can be an important part of the solution to the problems now reaching crisis proportions in American emergency rooms" (7).

References

- Appleby J. Hospitals plagued by on-call shortage. USA Today June 16. 1999.

- Blaming the docs: patient dumping probes see physicians as culprits in turning away indigent from ERs. Modern Healthcare August 9, 1999.

- Winston K, The Advisory Board Company, Clinical Initiatives Center. Cause for concern: ensuring adequate and timely on-call physician coverage in the emergency department. ED Watch Issue #4, May 2, 2000.

- Foubister V. Is there a dearth of specialists in the ED? American Medical News July 12, 1999.

- Wanted: doctors willing to take ER call. ACP-ASIM Observer American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, November 2001.

- Aronson M, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Personal interview. December 2004.

- Angus R, letter to the editor, ACP-ASIM Observer American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, December 2001.

In the 1970s and 1980s, indigent patients experienced problems at hospital Emergency Departments (EDs) around the country. They were refused care and shuttled to other facilities for services. To protect patients against these types of abuses, Congress passed The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA).·

EMTALA mandates that all patients presenting to the ED - regardless of insurance status - receive a medical screening examination and be medically stable prior to transfer to another facility. If a hospital has the facilities to treat the emergency, the patient can not be transferred to another ED. To address these requirements, every hospital must have physicians on call to assist emergency physicians in assessing and treating unassigned patients.

By the late 1990s, as EMTALA requirements took hold, inadequate on-call physician coverage reached crisis proportions and became a front page issue. In 1999, USA Today carried the following headline: "A Care Crisis in ERs: Nation's Hospitals Plagued by Shortage of On-Call Specialists" (1). In that same year, Modem Healthcare ran an article with the following headline: "Blaming the Docs: Patient Dumping Probes See Physicians as Culprits in Turning Away Indigent from ERs" (2). In California, a task force was formed to address the matter (3), and the American Medical Association (AMA) began exploring solutions at the highest levels (4).

Why do hospitals have problems organizing their medical staff to be available to provide on-call treatment of unassigned patients in the ED and subsequent to admission? There appear to be three major reasons for this problem.

First, at a minimum, on-call treatment of unassigned patients creates an inconvenience for physicians, taking away from their personal time; worse. it can reduce the number of available hours they have to spend with their office-based patients.

Second, there are financial disincentives to on-call coverage. Often unassigned patients presenting in the ED are uninsured or under-insured. On-call physicians frequently do not receive adequate compensation for the task of treating these patients.

Finally, on-call duty can bring bureaucratic hassles and/or legal liability for physicians. Dealing with state Medicaid agencies may require addressing administrative requirements, completing paperwork, and paying penalties for not following the rules.

Richard Frankenstein, MD, a pulmonologist in Southern California, admitted an uninsured patient with multiple chronic illnesses when he was the on-call physician at one of his affiliated hospitals. The patient spent 8 weeks in the hospital, much of that time in intensive care. Frankenstein often visited this patient twice a day, so his already busy schedule began hour earlier and ended 1 hour later. He received no compensation for these efforts. That commitment dragged me away from my primary responsibilities,” said Frankenstein. "I'm no longer on staff there, and that situation was a major reason that I resigned (5).

During the past 5 years, the crisis of on-call physician coverage has been significantly reduced and hospitalists emerge as one of the major reasons why. Although there are still issues related to the availability of on-call specialists and surgeons, hospitals that have implemented hospital medicine programs are able to make available experienced general internists to triage, admit, and treat unassigned patients.

Hospital Medicine Programs:

A Value Added Resource to Hospitals

Hospital medicine programs are characterized by several unique features that facilitate the treatment of unassigned patients and result in significant benefits for hospitals. Figure 1 above illustrates these relationships.

Mark Aronson, MD, serves as a member of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), a 5O0-bed academic medical center in Boston and is also Vice Chairman for Quality and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. BIDMC has a mature hospital medicine program, and approximately 55-60% of the program's patients are unassigned, representing more than 25% of the hospital's general medicine census. Aronson believes that the hospital medicine program provides value to both patients and the institution. He described a case in which a nursing home patient without health insurance presented in the ED. After the initial evaluation, the ED attending decided to admit the patient. One of the hospitalists recognized the patient as someone he had treated several times before. He knew that her medical condition would not require hospitalization and arranged the appropriate treatment, allowing for transfer back to the nursing home. “In this situation, because the hospitalist had a relationship and history with the unassigned patient, the patient received timely, quality medical care and the hospital saved a significant amount of money” (5).

In the ED, the prompt and efficient treatment of unassigned patients can reduce backlogs and minimize hassles for emergency physicians. There is no need for the emergency physician to track down an on-call physician to admit the patient. The ED maintains a better work flow and makes better use of their resources, especially of physician and nursing time as well as space. Most hospitalists are familiar with pertinent laws (e.g., EMTALA) and insurance company policies, thereby spending less time investigating and resolving problems. The hospitals benefits through improved throughput.

"We have a high-volume ED with a large percentage of unassigned patients. In addition our hospital census is often 120% at midday and 90% at midnight. Efficient flow of patients though the ED at all hours is a critical issue at our hospital," says Patrick Cawley, MD, Director of Hospitalist Services at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. "We have been asked to lead throughput initiatives which have resulted in a dramatic reduction in backlogs and the movement of patients out of the ED either to a bed or possibly to an alternative setting.”

The members of the medical staff of a hospital are often the driving force for the creation of a hospital medicine program. Having hopitalists at their institution may mean that affiliated physicians do not have to assume the undesirable responsibilities of participating in an on-call schedule. Furthermore, since hospitalists typically do not have an office practice, community physicians still have the opportunity to care for the unassigned patients once they are discharged, thereby building their practice. Hospitals can refer the patients according to an equitable schedule approved by the medical staff. By addressing issues related to on-call physician coverage, a hospital can improve medical staff relations.

At Winchester Medical Center in Virginia, family practitioners in the area surrendered their admitting privileges, creating an onerous call schedule for generalist internists. The hospital hired four hospitalists to admit and treat all unassigned patients. Instead of taking call, the internists are part of a primary care roster and rotate responsibility for unassigned patients once they are discharged (6). It has been a win-win solution for the hospital and the medical staff.

Often the unassigned patients have significant discharge planning and placement problems, especially those that are uninsured. While these issues can be daunting to the office-based physicians, hospitalists usually have a more comprehensive knowledge of the resources of the hospital and the community to help solve these placement and post-discharge care issues.

In treating unassigned patients, hospitalists blend their clinical skills with knowledge of their hospital’s objectives, concerns, policies, and procedures. Since they are a relatively small, cohesive group within the institution, hospitalists are often familiar with practice guidelines, medical records documentation requirements, computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems, quality initiatives, and utilization management requirements.

"The hospitalists’ responsibilities in our program must have a good citizenship component," says Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, Director of the Inpatient Medicine Service at Merry Medical Center in Springfield, MA and co-founder of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). "Each physician must serve on a committee, a project, or a program that serves the hospital. Hospitalists are often the leaders of hospital-wide initiatives directed at quality of care, utilization management, and throughput.”

Stakeholder Analysis

By treating unassigned patients, hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. The benefits to these stakeholders are summarized in Table 1.

Assigning Value to Hospitalists' Work

Hospitalists typically manage unassigned and uninsured patients as part of their regular job duties. It is important that the administrator or leader of the hospital medicine group have a budgetary understanding of how to "score" the services that the hospitalists provide to these patients.

If the hospitalist service is provided by an independent, contracted group, they may be paid for treating the unassigned, uninsured patients. Often the payment is in the form of a case rate, based on the "average" number of services provided in an admission and using a Medicare or other mutually agreed upon fee schedule.

If the hospitalists are employees of the hospital, it is expected that they will assume responsibility for unassigned, uninsured patients. Although the hospital medicine group will not receive direct reimbursement for seeing these patients (unlike a contracted hospitalist group), the value of this service to the hospital must be recognized. In these situations, hospital administrators should acknowledge the critical need to credit the hospitalists for real work that must be performed but that generates little or no revenue. An equivalent case rate can be credited as a paper transaction to the hospitalist group to address the value of these services.

Conclusion

Given the current economic environment, the issue of treating unassigned and uninsured patients will not soon diminish. Demand is likely to increase with the nationwide growth in the number of uninsured patients. Physician resistance to call coverage and the rise of malpractice premiums will continue to create more pressure for hospitals to find solutions to this crisis. "We recognize that hospitalists are only part of the solution," says Ron Angus, MS, Past President of SHM. "Hospitals and government agencies must provide funding to cover the costs of inpatient care for acutely ill, uninsured - and usually unassigned - patients. Hospitals must also find ways to ensure that other specialists are available to hospitalists for acutely ill inpatients who require specialty expertise or procedures. With such cooperation and participation, hospitalists can be an important part of the solution to the problems now reaching crisis proportions in American emergency rooms" (7).

References

- Appleby J. Hospitals plagued by on-call shortage. USA Today June 16. 1999.

- Blaming the docs: patient dumping probes see physicians as culprits in turning away indigent from ERs. Modern Healthcare August 9, 1999.

- Winston K, The Advisory Board Company, Clinical Initiatives Center. Cause for concern: ensuring adequate and timely on-call physician coverage in the emergency department. ED Watch Issue #4, May 2, 2000.

- Foubister V. Is there a dearth of specialists in the ED? American Medical News July 12, 1999.

- Wanted: doctors willing to take ER call. ACP-ASIM Observer American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, November 2001.

- Aronson M, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Personal interview. December 2004.

- Angus R, letter to the editor, ACP-ASIM Observer American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, December 2001.