User login

› Explore the potential benefits of team-based care by conducting a full assessment of your practice, including patient panels, payer mix, current finances, regional pay-for-performance programs, leadership support, and your staff’s training and talents. A

› Consider partnering with a local pharmacist or with insurers to use their community health workers, nurse case managers, and other self-management support tools. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim” approach to optimizing the delivery of health care in the United States calls for improving the patient’s experience of care, including both quality and satisfaction; improving the health of populations; and reducing the per-capita cost of health care.1 Unfortunately, achieving these goals is being made more challenging by a perfect storm of conditions: The age of the population and the number of people accessing the systems are increasing, while the number of providers available to care for these patients is decreasing. The number of annual office visits to family physicians (FPs) in the United States is projected to increase from 462 million in 2008 to 565 million in 2025, which will require an estimated 51,880 additional FPs.2

One of the health care delivery models that has recently gained traction to help address this is team-based care. By practicing in a team-based care model, physicians and other clinicians can care for more patients, better manage those with high-risk and high-cost needs, and improve overall quality of care and satisfaction for all involved. Here we review the evidence for team-based care and its use for chronic disease management, and offer suggestions for its implementation.

The many providers who comprise the team

There is little consistency in the definition, composition, training, or maintenance of health care teams. Naylor et al3 defined team-based care as “the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care.”

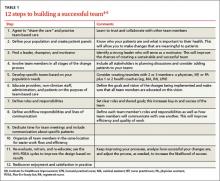

While the team construct will vary based on the needs of your practice and your patients, developing a high-functioning team is essential to achieving success. Our 12-step checklist for building a successful team is a good starting point (TABLE 1).4-6 Many other resources are available to help with each step of this process (TABLE 2).

Teams should be led by a primary care provider—a physician, nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA)—and consist of other members that complement the other’s expertise and roles, such as nurse case managers, clinical pharmacists, social workers, and behavioral health experts. Some practices have large teams with interdisciplinary members, including pharmacists, PAs, and NPs (the “expanded staffing” model), while others form smaller “teamlets” consisting of a physician and a registered nurse (RN) who serves as a health coach.

In the expanded staffing model, RNs and clinical pharmacists assume greater care management, while medical assistants (MAs) and licensed practice nurses (LPNs) are responsible for pre-visit, outreach, and follow-up activities.7 Redefining roles can spread the work among all team members, which allows each member to work to their level of training and licensure and permits the MD/NP/PA to focus on more complex tasks.

The teamlet model has 2 main features: 1) Patient encounters involve a clinician (MD, NP, PA) and a health coach (MA, RN, LPN); and 2) Care is expanded beyond the usual 15-minute visit to include pre-visit, visit, post-visit, and between-visit care.8 Incorporating a health coach puts an increased focus on the patient and self-management support, with the goals of increasing satisfaction for both the patient and the health care team, improving outcomes, and lowering cost due to fewer emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions/readmissions.

Smaller teams seem to be more effective and more manageable.8,9 In one example of well-functioning teamlet composed of RNs and MAs, an MA is responsible for patients coming in for timely chronic and preventive care needs, while the RNs focus their efforts on tasks that require their expertise, including health coaching, self-management support, and patient education.9 Although smaller offices may not have the resources of a large academic practice, this model of maximizing the role of the MAs is reasonable and achievable.

Another example of a successful teamlet model is a clinical microsystem, in which a small group of clinicians and support staff work together to provide care to a discrete group of patients.10,11 (For more information on clinical microsystems, go to the Dartmouth Institute Microsystem Academy at https://clinicalmicrosystem.org.)

What are the barriers to creating team-based care?

Many providers and administrators are concerned about the costs of creating a team-based model of care. These include the cost of hiring new staff, retraining current staff, and educating team members and patients, as well as the cost of developing and maintaining the necessary information technology.

There is, of course, always the concern about physicians relinquishing patient care tasks to other team members. The flip side of that is that staff members may not be eager to increase their roles and responsibilities. In addition, developing a high-functioning team requires ongoing efforts to train and retrain, as well as dedicated leadership and an ongoing commitment to team building.12

Team-based care can work well for managing chronic diseases

Despite the challenges of developing and maintaining this approach to care, the evidence suggests that implementing a team-based model can be especially useful for patients with chronic diseases, because it can improve patient outcomes and access to care, decrease costs, and improve clinician satisfaction—as detailed below.

Improved patient outcomes. Initial evidence suggests that implementing a team-based model can improve patients’ health and experience of care.13,14 The most positive findings have been observed for team-based efforts at managing specific diseases, such as diabetes and congestive heart failure (CHF), or specific populations, such as older patients with chronic illness. Studies have shown that using a team approach results in improved metrics, including HbA1c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure (BP), and body mass index.7,15-20 Team-based models that pair physicians and other primary care providers with a clinical pharmacist have increased patients’ medication adherence and provider adherence to recommended prescribing habits.15,21-23

One small clinical microsystem that focused on self-management support with health coaching increased patients’ ratings of their confidence in self-management from 40% to 60% at baseline to 80% to 90% after one year. This program also increased the proportion of patients in whom BP was controlled by 10% to 15%.10

Despite these successes, some team-based models may not always be “doable” because of the costs of adding an advanced practice clinician to the staff, or the challenges of recruiting the right person for the job. (How to adapt team-based care for smaller practices is discussed below.)

Improved access to care. A preponderance of data shows that team-based care increases the volume of patient visits, thereby improving access to care.7,21,24-28 The critical elements to successfully achieving this are effective training and delegation. In private practice, using well-trained clinical assistants to create a physician-driven team can increase patient visit volume by an estimated 30% (using 1 assistant) to 60% (using 2 assistants).24

Similar increases in visit volume are seen in larger patient-centered medical home (PCMH) models that consist of physicians, PAs or NPs, MAs, LPNs, RNs, and clinical pharmacists.7,25 Teams with defined ratios of assistants to physicians/NPs/PAs see the most patients per day compared to care coordinator models (ie, 1 assistant for multiple physicians) or enhanced traditional models.21 When focusing on disease-specific care, the impact on access can be even greater. A diabetes-specific team-based care program resulted in a >50% increase in daily patient encounters and 4-fold increase in annual office visits.28

In addition to increasing visits, team-based care also increases access to care by decreasing wait times for an appointment and increasing the use of secure messaging and telephone visits.7,25 In a prospective cohort pilot study of more than 2000 patients enrolled in a team-based care model, the average scheduling time for a face-to-face visit for nonurgent care decreased from a mean of 26.5 days to 14 days, compared to a mean of 31.5 days to 17.8 days for controls.25 (The decrease in the control group was likely due to implementation of an electronic medical record in the practice.) Furthermore, a non-controlled evaluation of health plan-based practice groups with very large patient populations (ie, >300,000 patients) reported up to a 3-fold decrease in appointment waiting time when using a team-based model.29

Some studies have found a decrease in office visits after implementing team-based care.7 However, these reports also found a corresponding increase (by as much as 80%) in the use of secure messaging and telephone encounters, which translated to an overall enhanced communication with patients and ultimately increased access to care.7

Decreased costs. Several controlled trials have looked at the financial impact of using team-based care to manage chronic conditions such as asthma, CHF, and diabetes. Rich et al30 found a nurse-directed program of patient self-management support via telephone and home visit follow-up was associated with a 56% reduction in hospital readmissions, which translated to a $460 decrease in cost per patient over a 3-month period compared to a control group. In a study by Domurat,31 hospital stays were 50% shorter for high-risk diabetes patients who were managed by a team that offered planned visits, telephone contact, and group visits; this resulted in a lower cost of care. Katon et al32 found that when a nurse manager was added to a primary care team to enhance self-management support, intensify treatment, and coordinate continuity of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions, outpatient health costs were decreased by $594 per patient over 24 months.

Liu et al33 randomly assigned 354 patients in a VA primary care clinic who met criteria for major depression or dysthymia to usual care or a collaborative care model. The collaborative care model included a mental health care team that provided telephone contact to encourage medication adherence and reviewed and suggested modifications to the treatment plan. After an initial expenditure of $519 per patient, a savings of approximately $33 per patient for total outpatient costs was realized.

A team-based coordinated care program for patients with multiple chronic conditions reduced patient visits to specialists by 24%, ED visits by 13%, and hospitalizations by 39%.34 An internal evaluation found that the program saved money by reducing admissions, including intensive care unit stays and “observational” stays for Medicare fee-for-service patients.35

What about reimbursement? Most studies that have evaluated the financial aspects of implementing team-based care have calculated the cost savings for the health system—rather than for an individual practice—through decreased hospital admissions, readmissions, and ED visits. Efficient, high-quality teams will require a substantial initial investment of time and hiring and training of staff before savings can be realized.

Team-based care may not be financially sustainable unless current reimbursement models are changed. The current US system bases payment on quantity of care instead of quality of care, reimburses only for clinician services, and does not compensate teams.36 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to recognize the need to reimburse for services that are not delivered in face-to-face patient encounters. For example, the agency established a new G-code that can be used for non-face-to-face care management services for Medicare patients with 2 or more significant chronic conditions; this code took effect on January 1, 2015.37

Some insurers are reimbursing practices for obtaining designation as a PCMH. This type of reimbursement could be expanded to include other types of team-based efforts—such as self-management support and health coaching.

Improved team satisfaction. While many primary care providers are experiencing fatigue and burnout,38 support staff in many practices also experience job dissatisfaction, which leads to increased absenteeism and high turnover. Several studies indicate that involving all levels of staff in the improvement process and empowering them to work to their full potential by enhancing their roles and realigning responsibilities can increase satisfaction.7,11,21,38,39 This in turn can lead to increased loyalty, commitment, and productivity, with decreased burnout and turnover.

TABLE 2

| Team-based care: Additional resources | |

| Resource | Comments |

The Dartmouth Institute Microsystem Academy | This site includes assessment tools and strategies for implementing clinical microsystems into practices |

Improving Chronic Illness Care | This site provides information about the chronic care model, care coordination, and patient-centered medical homes |

TeamSTEPPS | TeamSTEPPS is an evidence-based teamwork system to improve communication and teamwork skills among health care professionals. All resources, including training materials, are free and downloadable |

Godfrey MM, Melin CN, Muething SE, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 3. Transformation of two hospitals using microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem strategies. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:591-603. | This article provides resources and strategies to engage all levels of the health system in team-based care |

McKinley KE, Berry SA, Laam LA, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 4. Building innovative population-specific mesosystems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:655-663. | This article describes how to engage leadership at the health systems level |

Adapting team-based care for smaller practices

Physicians who practice alone or in small groups may have limited capacity to employ allied health professionals. However, your “team” doesn’t need to be housed only in your office. One innovative approach is the community-based medical home, where physicians with medical homes and/or care teams in their offices refer to, and collaborate with, a network of community-based professionals and agencies for clinical and social service support for their patients.22 Some options are to partner with a local pharmacist or with insurers to use their community health workers, nurse case managers, and other self-management support tools.

While having team-based care strategies is necessary to achieve a PCMH designation, you do not need to seek such designation in order to practice team-based care. Start by conducting a full assessment of your practice, including patient panels, payer mix, current finances, regional pay-for-performance programs, leadership support, and your staff’s training and talents. In addition, determine what you value for your practice and what outcomes you hope for, along with a clear plan of how to measure these outcomes. This will allow you to determine if the estimated cost of the proposed strategy is “worth it” in terms of your individual situation and goals.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michele Q. Zawora, MD, Thomas Jefferson University, 1015 Walnut Street, Suite 401, Philadelphia, Pa 19107; michele.zawora@jefferson.edu

1. Institute of Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Web site. Available at http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2015.

2.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503-509.

3. Naylor MD, Coburn KD, Kurtzman ET, et al. Inter-professional team-based primary care for chronically ill adults: State of the science. White paper presented at: the ABIM Foundation meeting to Advance Team-Based Care for the Chronically Ill in Ambulatory Settings; March 24-25, 2010; Philadelphia, PA.

4.Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, et al. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s Retooling for an Aging America report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2328-2337.

5.Kuzel AJ. Keys to high-functioning office teams. Family Practice Management. 2011;18:15-18.

6.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

7. Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The Group Health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:835-843.

8. Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:457-461.

9. Chen EH, Thom DH, Hessler DM, et al. Using the teamlet model to improve chronic care in an academic primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 4):S610-S614.

10. Wasson JH, Anders SG, Moore LG, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 2. Learning from micro practices about providing patients the care they want and need. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:445-452.

11. Williams I, Dickinson H, Robinson S. Clinical microsystems: An evaluation. Health Services Management Centre, School of Public Policy, University of Birmingham, England; 2007. Available at: http://chain.ulcc.ac.uk/chain/documents/hsmc_evaluation_report_CMS2007final.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2015.

12. Willard R, Bodenheimer T. The building blocks of high-performing primary care: Lessons from the field. April 2012. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/B/PDF%20BuildingBlocksPrimaryCare.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569-572.

14. Boult C, Karm L, Groves C. Improving chronic care: the “guided care” model. Perm J. 2008;12:50-54.

15. Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD006560.

16. Bloom FJ, Graf TR, Steele GD. Improved patient outcomes in 3 years with a system of care for diabetes. October 2012. Available at: http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2012/Commentaries/VSRT-Improved-Patient-Outcomes.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Bloom FJ Jr, Yan X, Stewart WF, et al. Primary care diabetes bundle management: 3-year outcomes for microvascular and macrovascular events. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:e175-e182.

18. Pape GA, Hunt JS, Butler KL, et al. Team-based care approach to cholesterol management in diabetes mellitus: two-year cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1480-1486.

19. Scanlon DP, Hollenbeak CS, Beich J, et al. Financial and clinical impact of team-based treatment for medicaid enrollees with diabetes in a federally qualified health center. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2160-2165.

20. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, et al. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD001481.

21. Goldberg GD, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, et al. Team-based care: a critical element of primary care practice transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16:150-156.

22. Lipton HL. Home is where the health is: advancing team-based care in chronic disease management. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1945-1948.

23. Farris KB, Côté I, Feeny D, et al. Enhancing primary care for complex patients. Demonstration project using multidisciplinary teams. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:998-1003.

24. Anderson P, Halley MD. A new approach to making your doctor-nurse team more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

25. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T, Grundy P. The outcomes of implementing patient-centered medical home interventions: A review of the evidence on quality, access and costs from recent prospective evaluation studies, August 2009. Washington, DC; Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2009.

26. Smith M, Giuliano MR, Starkowski MP. In Connecticut: improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:646-654.

27. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;16:955-964.

28. Bray P, Roupe M, Young S, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of system redesign for diabetes care management in rural areas: the eastern North Carolina experience. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31:712-718.

29. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health Partners uses “BestCare” practices to improve care and outcomes, reduce costs. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Web site. Available at http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Documents/IHITripleAimHealthPartnersSummaryofSuccessJul09v2.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

30. Rich MW, Beckman V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190-1195.

31. Domurat ES. Diabetes managed care and clinical outcomes: the Harbor City, California Kaiser Permanente diabetes care system. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:1299-1307.

32. Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:506-514.

33. Liu CF, Hendrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in a primary care veteran population. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:698-704.

34. Berenson RA; The Urban Institute. Challenging the status quo in chronic disease care: seven case studies. California Healthcare Foundation: 2006. California HealthCare Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/C/PDF%20ChallengingStatusQuoCaseStudies.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

35. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, et al. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1817-1825.

36. Schneider ME. Medicare finalizes plan for non-face-to-face payments. Family Practice News Web site. Available at: http://www.familypracticenews.com/?id=2633&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=226457&cHash=2aeafe0585c7156dcf23891d010cd12f. Accessed December 2, 2013.

37. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact sheets: Policy and payment changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2015. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/newsroom/mediareleasedatabase/fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-10-31-7.html. Accessed February 13, 2015.

38. Berry LL, Dunham J. Redefining the patient experience with collaborative care. Harvard Business Review Blog Network. Harvard Business Review Web site. Available at: https://hbr.org/2013/09/redefining-the-patient-experience-with-collaborative-care/. Accessed February 5, 2015.

39. Lyon RK, Slawson J. An organized approach to chronic disease care. Fam Pract Manag. 2011;18:27-31.

› Explore the potential benefits of team-based care by conducting a full assessment of your practice, including patient panels, payer mix, current finances, regional pay-for-performance programs, leadership support, and your staff’s training and talents. A

› Consider partnering with a local pharmacist or with insurers to use their community health workers, nurse case managers, and other self-management support tools. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim” approach to optimizing the delivery of health care in the United States calls for improving the patient’s experience of care, including both quality and satisfaction; improving the health of populations; and reducing the per-capita cost of health care.1 Unfortunately, achieving these goals is being made more challenging by a perfect storm of conditions: The age of the population and the number of people accessing the systems are increasing, while the number of providers available to care for these patients is decreasing. The number of annual office visits to family physicians (FPs) in the United States is projected to increase from 462 million in 2008 to 565 million in 2025, which will require an estimated 51,880 additional FPs.2

One of the health care delivery models that has recently gained traction to help address this is team-based care. By practicing in a team-based care model, physicians and other clinicians can care for more patients, better manage those with high-risk and high-cost needs, and improve overall quality of care and satisfaction for all involved. Here we review the evidence for team-based care and its use for chronic disease management, and offer suggestions for its implementation.

The many providers who comprise the team

There is little consistency in the definition, composition, training, or maintenance of health care teams. Naylor et al3 defined team-based care as “the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care.”

While the team construct will vary based on the needs of your practice and your patients, developing a high-functioning team is essential to achieving success. Our 12-step checklist for building a successful team is a good starting point (TABLE 1).4-6 Many other resources are available to help with each step of this process (TABLE 2).

Teams should be led by a primary care provider—a physician, nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA)—and consist of other members that complement the other’s expertise and roles, such as nurse case managers, clinical pharmacists, social workers, and behavioral health experts. Some practices have large teams with interdisciplinary members, including pharmacists, PAs, and NPs (the “expanded staffing” model), while others form smaller “teamlets” consisting of a physician and a registered nurse (RN) who serves as a health coach.

In the expanded staffing model, RNs and clinical pharmacists assume greater care management, while medical assistants (MAs) and licensed practice nurses (LPNs) are responsible for pre-visit, outreach, and follow-up activities.7 Redefining roles can spread the work among all team members, which allows each member to work to their level of training and licensure and permits the MD/NP/PA to focus on more complex tasks.

The teamlet model has 2 main features: 1) Patient encounters involve a clinician (MD, NP, PA) and a health coach (MA, RN, LPN); and 2) Care is expanded beyond the usual 15-minute visit to include pre-visit, visit, post-visit, and between-visit care.8 Incorporating a health coach puts an increased focus on the patient and self-management support, with the goals of increasing satisfaction for both the patient and the health care team, improving outcomes, and lowering cost due to fewer emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions/readmissions.

Smaller teams seem to be more effective and more manageable.8,9 In one example of well-functioning teamlet composed of RNs and MAs, an MA is responsible for patients coming in for timely chronic and preventive care needs, while the RNs focus their efforts on tasks that require their expertise, including health coaching, self-management support, and patient education.9 Although smaller offices may not have the resources of a large academic practice, this model of maximizing the role of the MAs is reasonable and achievable.

Another example of a successful teamlet model is a clinical microsystem, in which a small group of clinicians and support staff work together to provide care to a discrete group of patients.10,11 (For more information on clinical microsystems, go to the Dartmouth Institute Microsystem Academy at https://clinicalmicrosystem.org.)

What are the barriers to creating team-based care?

Many providers and administrators are concerned about the costs of creating a team-based model of care. These include the cost of hiring new staff, retraining current staff, and educating team members and patients, as well as the cost of developing and maintaining the necessary information technology.

There is, of course, always the concern about physicians relinquishing patient care tasks to other team members. The flip side of that is that staff members may not be eager to increase their roles and responsibilities. In addition, developing a high-functioning team requires ongoing efforts to train and retrain, as well as dedicated leadership and an ongoing commitment to team building.12

Team-based care can work well for managing chronic diseases

Despite the challenges of developing and maintaining this approach to care, the evidence suggests that implementing a team-based model can be especially useful for patients with chronic diseases, because it can improve patient outcomes and access to care, decrease costs, and improve clinician satisfaction—as detailed below.

Improved patient outcomes. Initial evidence suggests that implementing a team-based model can improve patients’ health and experience of care.13,14 The most positive findings have been observed for team-based efforts at managing specific diseases, such as diabetes and congestive heart failure (CHF), or specific populations, such as older patients with chronic illness. Studies have shown that using a team approach results in improved metrics, including HbA1c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure (BP), and body mass index.7,15-20 Team-based models that pair physicians and other primary care providers with a clinical pharmacist have increased patients’ medication adherence and provider adherence to recommended prescribing habits.15,21-23

One small clinical microsystem that focused on self-management support with health coaching increased patients’ ratings of their confidence in self-management from 40% to 60% at baseline to 80% to 90% after one year. This program also increased the proportion of patients in whom BP was controlled by 10% to 15%.10

Despite these successes, some team-based models may not always be “doable” because of the costs of adding an advanced practice clinician to the staff, or the challenges of recruiting the right person for the job. (How to adapt team-based care for smaller practices is discussed below.)

Improved access to care. A preponderance of data shows that team-based care increases the volume of patient visits, thereby improving access to care.7,21,24-28 The critical elements to successfully achieving this are effective training and delegation. In private practice, using well-trained clinical assistants to create a physician-driven team can increase patient visit volume by an estimated 30% (using 1 assistant) to 60% (using 2 assistants).24

Similar increases in visit volume are seen in larger patient-centered medical home (PCMH) models that consist of physicians, PAs or NPs, MAs, LPNs, RNs, and clinical pharmacists.7,25 Teams with defined ratios of assistants to physicians/NPs/PAs see the most patients per day compared to care coordinator models (ie, 1 assistant for multiple physicians) or enhanced traditional models.21 When focusing on disease-specific care, the impact on access can be even greater. A diabetes-specific team-based care program resulted in a >50% increase in daily patient encounters and 4-fold increase in annual office visits.28

In addition to increasing visits, team-based care also increases access to care by decreasing wait times for an appointment and increasing the use of secure messaging and telephone visits.7,25 In a prospective cohort pilot study of more than 2000 patients enrolled in a team-based care model, the average scheduling time for a face-to-face visit for nonurgent care decreased from a mean of 26.5 days to 14 days, compared to a mean of 31.5 days to 17.8 days for controls.25 (The decrease in the control group was likely due to implementation of an electronic medical record in the practice.) Furthermore, a non-controlled evaluation of health plan-based practice groups with very large patient populations (ie, >300,000 patients) reported up to a 3-fold decrease in appointment waiting time when using a team-based model.29

Some studies have found a decrease in office visits after implementing team-based care.7 However, these reports also found a corresponding increase (by as much as 80%) in the use of secure messaging and telephone encounters, which translated to an overall enhanced communication with patients and ultimately increased access to care.7

Decreased costs. Several controlled trials have looked at the financial impact of using team-based care to manage chronic conditions such as asthma, CHF, and diabetes. Rich et al30 found a nurse-directed program of patient self-management support via telephone and home visit follow-up was associated with a 56% reduction in hospital readmissions, which translated to a $460 decrease in cost per patient over a 3-month period compared to a control group. In a study by Domurat,31 hospital stays were 50% shorter for high-risk diabetes patients who were managed by a team that offered planned visits, telephone contact, and group visits; this resulted in a lower cost of care. Katon et al32 found that when a nurse manager was added to a primary care team to enhance self-management support, intensify treatment, and coordinate continuity of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions, outpatient health costs were decreased by $594 per patient over 24 months.

Liu et al33 randomly assigned 354 patients in a VA primary care clinic who met criteria for major depression or dysthymia to usual care or a collaborative care model. The collaborative care model included a mental health care team that provided telephone contact to encourage medication adherence and reviewed and suggested modifications to the treatment plan. After an initial expenditure of $519 per patient, a savings of approximately $33 per patient for total outpatient costs was realized.

A team-based coordinated care program for patients with multiple chronic conditions reduced patient visits to specialists by 24%, ED visits by 13%, and hospitalizations by 39%.34 An internal evaluation found that the program saved money by reducing admissions, including intensive care unit stays and “observational” stays for Medicare fee-for-service patients.35

What about reimbursement? Most studies that have evaluated the financial aspects of implementing team-based care have calculated the cost savings for the health system—rather than for an individual practice—through decreased hospital admissions, readmissions, and ED visits. Efficient, high-quality teams will require a substantial initial investment of time and hiring and training of staff before savings can be realized.

Team-based care may not be financially sustainable unless current reimbursement models are changed. The current US system bases payment on quantity of care instead of quality of care, reimburses only for clinician services, and does not compensate teams.36 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to recognize the need to reimburse for services that are not delivered in face-to-face patient encounters. For example, the agency established a new G-code that can be used for non-face-to-face care management services for Medicare patients with 2 or more significant chronic conditions; this code took effect on January 1, 2015.37

Some insurers are reimbursing practices for obtaining designation as a PCMH. This type of reimbursement could be expanded to include other types of team-based efforts—such as self-management support and health coaching.

Improved team satisfaction. While many primary care providers are experiencing fatigue and burnout,38 support staff in many practices also experience job dissatisfaction, which leads to increased absenteeism and high turnover. Several studies indicate that involving all levels of staff in the improvement process and empowering them to work to their full potential by enhancing their roles and realigning responsibilities can increase satisfaction.7,11,21,38,39 This in turn can lead to increased loyalty, commitment, and productivity, with decreased burnout and turnover.

TABLE 2

| Team-based care: Additional resources | |

| Resource | Comments |

The Dartmouth Institute Microsystem Academy | This site includes assessment tools and strategies for implementing clinical microsystems into practices |

Improving Chronic Illness Care | This site provides information about the chronic care model, care coordination, and patient-centered medical homes |

TeamSTEPPS | TeamSTEPPS is an evidence-based teamwork system to improve communication and teamwork skills among health care professionals. All resources, including training materials, are free and downloadable |

Godfrey MM, Melin CN, Muething SE, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 3. Transformation of two hospitals using microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem strategies. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:591-603. | This article provides resources and strategies to engage all levels of the health system in team-based care |

McKinley KE, Berry SA, Laam LA, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 4. Building innovative population-specific mesosystems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:655-663. | This article describes how to engage leadership at the health systems level |

Adapting team-based care for smaller practices

Physicians who practice alone or in small groups may have limited capacity to employ allied health professionals. However, your “team” doesn’t need to be housed only in your office. One innovative approach is the community-based medical home, where physicians with medical homes and/or care teams in their offices refer to, and collaborate with, a network of community-based professionals and agencies for clinical and social service support for their patients.22 Some options are to partner with a local pharmacist or with insurers to use their community health workers, nurse case managers, and other self-management support tools.

While having team-based care strategies is necessary to achieve a PCMH designation, you do not need to seek such designation in order to practice team-based care. Start by conducting a full assessment of your practice, including patient panels, payer mix, current finances, regional pay-for-performance programs, leadership support, and your staff’s training and talents. In addition, determine what you value for your practice and what outcomes you hope for, along with a clear plan of how to measure these outcomes. This will allow you to determine if the estimated cost of the proposed strategy is “worth it” in terms of your individual situation and goals.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michele Q. Zawora, MD, Thomas Jefferson University, 1015 Walnut Street, Suite 401, Philadelphia, Pa 19107; michele.zawora@jefferson.edu

› Explore the potential benefits of team-based care by conducting a full assessment of your practice, including patient panels, payer mix, current finances, regional pay-for-performance programs, leadership support, and your staff’s training and talents. A

› Consider partnering with a local pharmacist or with insurers to use their community health workers, nurse case managers, and other self-management support tools. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim” approach to optimizing the delivery of health care in the United States calls for improving the patient’s experience of care, including both quality and satisfaction; improving the health of populations; and reducing the per-capita cost of health care.1 Unfortunately, achieving these goals is being made more challenging by a perfect storm of conditions: The age of the population and the number of people accessing the systems are increasing, while the number of providers available to care for these patients is decreasing. The number of annual office visits to family physicians (FPs) in the United States is projected to increase from 462 million in 2008 to 565 million in 2025, which will require an estimated 51,880 additional FPs.2

One of the health care delivery models that has recently gained traction to help address this is team-based care. By practicing in a team-based care model, physicians and other clinicians can care for more patients, better manage those with high-risk and high-cost needs, and improve overall quality of care and satisfaction for all involved. Here we review the evidence for team-based care and its use for chronic disease management, and offer suggestions for its implementation.

The many providers who comprise the team

There is little consistency in the definition, composition, training, or maintenance of health care teams. Naylor et al3 defined team-based care as “the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care.”

While the team construct will vary based on the needs of your practice and your patients, developing a high-functioning team is essential to achieving success. Our 12-step checklist for building a successful team is a good starting point (TABLE 1).4-6 Many other resources are available to help with each step of this process (TABLE 2).

Teams should be led by a primary care provider—a physician, nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA)—and consist of other members that complement the other’s expertise and roles, such as nurse case managers, clinical pharmacists, social workers, and behavioral health experts. Some practices have large teams with interdisciplinary members, including pharmacists, PAs, and NPs (the “expanded staffing” model), while others form smaller “teamlets” consisting of a physician and a registered nurse (RN) who serves as a health coach.

In the expanded staffing model, RNs and clinical pharmacists assume greater care management, while medical assistants (MAs) and licensed practice nurses (LPNs) are responsible for pre-visit, outreach, and follow-up activities.7 Redefining roles can spread the work among all team members, which allows each member to work to their level of training and licensure and permits the MD/NP/PA to focus on more complex tasks.

The teamlet model has 2 main features: 1) Patient encounters involve a clinician (MD, NP, PA) and a health coach (MA, RN, LPN); and 2) Care is expanded beyond the usual 15-minute visit to include pre-visit, visit, post-visit, and between-visit care.8 Incorporating a health coach puts an increased focus on the patient and self-management support, with the goals of increasing satisfaction for both the patient and the health care team, improving outcomes, and lowering cost due to fewer emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions/readmissions.

Smaller teams seem to be more effective and more manageable.8,9 In one example of well-functioning teamlet composed of RNs and MAs, an MA is responsible for patients coming in for timely chronic and preventive care needs, while the RNs focus their efforts on tasks that require their expertise, including health coaching, self-management support, and patient education.9 Although smaller offices may not have the resources of a large academic practice, this model of maximizing the role of the MAs is reasonable and achievable.

Another example of a successful teamlet model is a clinical microsystem, in which a small group of clinicians and support staff work together to provide care to a discrete group of patients.10,11 (For more information on clinical microsystems, go to the Dartmouth Institute Microsystem Academy at https://clinicalmicrosystem.org.)

What are the barriers to creating team-based care?

Many providers and administrators are concerned about the costs of creating a team-based model of care. These include the cost of hiring new staff, retraining current staff, and educating team members and patients, as well as the cost of developing and maintaining the necessary information technology.

There is, of course, always the concern about physicians relinquishing patient care tasks to other team members. The flip side of that is that staff members may not be eager to increase their roles and responsibilities. In addition, developing a high-functioning team requires ongoing efforts to train and retrain, as well as dedicated leadership and an ongoing commitment to team building.12

Team-based care can work well for managing chronic diseases

Despite the challenges of developing and maintaining this approach to care, the evidence suggests that implementing a team-based model can be especially useful for patients with chronic diseases, because it can improve patient outcomes and access to care, decrease costs, and improve clinician satisfaction—as detailed below.

Improved patient outcomes. Initial evidence suggests that implementing a team-based model can improve patients’ health and experience of care.13,14 The most positive findings have been observed for team-based efforts at managing specific diseases, such as diabetes and congestive heart failure (CHF), or specific populations, such as older patients with chronic illness. Studies have shown that using a team approach results in improved metrics, including HbA1c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure (BP), and body mass index.7,15-20 Team-based models that pair physicians and other primary care providers with a clinical pharmacist have increased patients’ medication adherence and provider adherence to recommended prescribing habits.15,21-23

One small clinical microsystem that focused on self-management support with health coaching increased patients’ ratings of their confidence in self-management from 40% to 60% at baseline to 80% to 90% after one year. This program also increased the proportion of patients in whom BP was controlled by 10% to 15%.10

Despite these successes, some team-based models may not always be “doable” because of the costs of adding an advanced practice clinician to the staff, or the challenges of recruiting the right person for the job. (How to adapt team-based care for smaller practices is discussed below.)

Improved access to care. A preponderance of data shows that team-based care increases the volume of patient visits, thereby improving access to care.7,21,24-28 The critical elements to successfully achieving this are effective training and delegation. In private practice, using well-trained clinical assistants to create a physician-driven team can increase patient visit volume by an estimated 30% (using 1 assistant) to 60% (using 2 assistants).24

Similar increases in visit volume are seen in larger patient-centered medical home (PCMH) models that consist of physicians, PAs or NPs, MAs, LPNs, RNs, and clinical pharmacists.7,25 Teams with defined ratios of assistants to physicians/NPs/PAs see the most patients per day compared to care coordinator models (ie, 1 assistant for multiple physicians) or enhanced traditional models.21 When focusing on disease-specific care, the impact on access can be even greater. A diabetes-specific team-based care program resulted in a >50% increase in daily patient encounters and 4-fold increase in annual office visits.28

In addition to increasing visits, team-based care also increases access to care by decreasing wait times for an appointment and increasing the use of secure messaging and telephone visits.7,25 In a prospective cohort pilot study of more than 2000 patients enrolled in a team-based care model, the average scheduling time for a face-to-face visit for nonurgent care decreased from a mean of 26.5 days to 14 days, compared to a mean of 31.5 days to 17.8 days for controls.25 (The decrease in the control group was likely due to implementation of an electronic medical record in the practice.) Furthermore, a non-controlled evaluation of health plan-based practice groups with very large patient populations (ie, >300,000 patients) reported up to a 3-fold decrease in appointment waiting time when using a team-based model.29

Some studies have found a decrease in office visits after implementing team-based care.7 However, these reports also found a corresponding increase (by as much as 80%) in the use of secure messaging and telephone encounters, which translated to an overall enhanced communication with patients and ultimately increased access to care.7

Decreased costs. Several controlled trials have looked at the financial impact of using team-based care to manage chronic conditions such as asthma, CHF, and diabetes. Rich et al30 found a nurse-directed program of patient self-management support via telephone and home visit follow-up was associated with a 56% reduction in hospital readmissions, which translated to a $460 decrease in cost per patient over a 3-month period compared to a control group. In a study by Domurat,31 hospital stays were 50% shorter for high-risk diabetes patients who were managed by a team that offered planned visits, telephone contact, and group visits; this resulted in a lower cost of care. Katon et al32 found that when a nurse manager was added to a primary care team to enhance self-management support, intensify treatment, and coordinate continuity of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions, outpatient health costs were decreased by $594 per patient over 24 months.

Liu et al33 randomly assigned 354 patients in a VA primary care clinic who met criteria for major depression or dysthymia to usual care or a collaborative care model. The collaborative care model included a mental health care team that provided telephone contact to encourage medication adherence and reviewed and suggested modifications to the treatment plan. After an initial expenditure of $519 per patient, a savings of approximately $33 per patient for total outpatient costs was realized.

A team-based coordinated care program for patients with multiple chronic conditions reduced patient visits to specialists by 24%, ED visits by 13%, and hospitalizations by 39%.34 An internal evaluation found that the program saved money by reducing admissions, including intensive care unit stays and “observational” stays for Medicare fee-for-service patients.35

What about reimbursement? Most studies that have evaluated the financial aspects of implementing team-based care have calculated the cost savings for the health system—rather than for an individual practice—through decreased hospital admissions, readmissions, and ED visits. Efficient, high-quality teams will require a substantial initial investment of time and hiring and training of staff before savings can be realized.

Team-based care may not be financially sustainable unless current reimbursement models are changed. The current US system bases payment on quantity of care instead of quality of care, reimburses only for clinician services, and does not compensate teams.36 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to recognize the need to reimburse for services that are not delivered in face-to-face patient encounters. For example, the agency established a new G-code that can be used for non-face-to-face care management services for Medicare patients with 2 or more significant chronic conditions; this code took effect on January 1, 2015.37

Some insurers are reimbursing practices for obtaining designation as a PCMH. This type of reimbursement could be expanded to include other types of team-based efforts—such as self-management support and health coaching.

Improved team satisfaction. While many primary care providers are experiencing fatigue and burnout,38 support staff in many practices also experience job dissatisfaction, which leads to increased absenteeism and high turnover. Several studies indicate that involving all levels of staff in the improvement process and empowering them to work to their full potential by enhancing their roles and realigning responsibilities can increase satisfaction.7,11,21,38,39 This in turn can lead to increased loyalty, commitment, and productivity, with decreased burnout and turnover.

TABLE 2

| Team-based care: Additional resources | |

| Resource | Comments |

The Dartmouth Institute Microsystem Academy | This site includes assessment tools and strategies for implementing clinical microsystems into practices |

Improving Chronic Illness Care | This site provides information about the chronic care model, care coordination, and patient-centered medical homes |

TeamSTEPPS | TeamSTEPPS is an evidence-based teamwork system to improve communication and teamwork skills among health care professionals. All resources, including training materials, are free and downloadable |

Godfrey MM, Melin CN, Muething SE, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 3. Transformation of two hospitals using microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem strategies. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:591-603. | This article provides resources and strategies to engage all levels of the health system in team-based care |

McKinley KE, Berry SA, Laam LA, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 4. Building innovative population-specific mesosystems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:655-663. | This article describes how to engage leadership at the health systems level |

Adapting team-based care for smaller practices

Physicians who practice alone or in small groups may have limited capacity to employ allied health professionals. However, your “team” doesn’t need to be housed only in your office. One innovative approach is the community-based medical home, where physicians with medical homes and/or care teams in their offices refer to, and collaborate with, a network of community-based professionals and agencies for clinical and social service support for their patients.22 Some options are to partner with a local pharmacist or with insurers to use their community health workers, nurse case managers, and other self-management support tools.

While having team-based care strategies is necessary to achieve a PCMH designation, you do not need to seek such designation in order to practice team-based care. Start by conducting a full assessment of your practice, including patient panels, payer mix, current finances, regional pay-for-performance programs, leadership support, and your staff’s training and talents. In addition, determine what you value for your practice and what outcomes you hope for, along with a clear plan of how to measure these outcomes. This will allow you to determine if the estimated cost of the proposed strategy is “worth it” in terms of your individual situation and goals.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michele Q. Zawora, MD, Thomas Jefferson University, 1015 Walnut Street, Suite 401, Philadelphia, Pa 19107; michele.zawora@jefferson.edu

1. Institute of Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Web site. Available at http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2015.

2.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503-509.

3. Naylor MD, Coburn KD, Kurtzman ET, et al. Inter-professional team-based primary care for chronically ill adults: State of the science. White paper presented at: the ABIM Foundation meeting to Advance Team-Based Care for the Chronically Ill in Ambulatory Settings; March 24-25, 2010; Philadelphia, PA.

4.Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, et al. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s Retooling for an Aging America report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2328-2337.

5.Kuzel AJ. Keys to high-functioning office teams. Family Practice Management. 2011;18:15-18.

6.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

7. Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The Group Health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:835-843.

8. Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:457-461.

9. Chen EH, Thom DH, Hessler DM, et al. Using the teamlet model to improve chronic care in an academic primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 4):S610-S614.

10. Wasson JH, Anders SG, Moore LG, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 2. Learning from micro practices about providing patients the care they want and need. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:445-452.

11. Williams I, Dickinson H, Robinson S. Clinical microsystems: An evaluation. Health Services Management Centre, School of Public Policy, University of Birmingham, England; 2007. Available at: http://chain.ulcc.ac.uk/chain/documents/hsmc_evaluation_report_CMS2007final.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2015.

12. Willard R, Bodenheimer T. The building blocks of high-performing primary care: Lessons from the field. April 2012. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/B/PDF%20BuildingBlocksPrimaryCare.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569-572.

14. Boult C, Karm L, Groves C. Improving chronic care: the “guided care” model. Perm J. 2008;12:50-54.

15. Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD006560.

16. Bloom FJ, Graf TR, Steele GD. Improved patient outcomes in 3 years with a system of care for diabetes. October 2012. Available at: http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2012/Commentaries/VSRT-Improved-Patient-Outcomes.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Bloom FJ Jr, Yan X, Stewart WF, et al. Primary care diabetes bundle management: 3-year outcomes for microvascular and macrovascular events. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:e175-e182.

18. Pape GA, Hunt JS, Butler KL, et al. Team-based care approach to cholesterol management in diabetes mellitus: two-year cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1480-1486.

19. Scanlon DP, Hollenbeak CS, Beich J, et al. Financial and clinical impact of team-based treatment for medicaid enrollees with diabetes in a federally qualified health center. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2160-2165.

20. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, et al. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD001481.

21. Goldberg GD, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, et al. Team-based care: a critical element of primary care practice transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16:150-156.

22. Lipton HL. Home is where the health is: advancing team-based care in chronic disease management. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1945-1948.

23. Farris KB, Côté I, Feeny D, et al. Enhancing primary care for complex patients. Demonstration project using multidisciplinary teams. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:998-1003.

24. Anderson P, Halley MD. A new approach to making your doctor-nurse team more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

25. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T, Grundy P. The outcomes of implementing patient-centered medical home interventions: A review of the evidence on quality, access and costs from recent prospective evaluation studies, August 2009. Washington, DC; Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2009.

26. Smith M, Giuliano MR, Starkowski MP. In Connecticut: improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:646-654.

27. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;16:955-964.

28. Bray P, Roupe M, Young S, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of system redesign for diabetes care management in rural areas: the eastern North Carolina experience. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31:712-718.

29. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health Partners uses “BestCare” practices to improve care and outcomes, reduce costs. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Web site. Available at http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Documents/IHITripleAimHealthPartnersSummaryofSuccessJul09v2.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

30. Rich MW, Beckman V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190-1195.

31. Domurat ES. Diabetes managed care and clinical outcomes: the Harbor City, California Kaiser Permanente diabetes care system. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:1299-1307.

32. Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:506-514.

33. Liu CF, Hendrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in a primary care veteran population. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:698-704.

34. Berenson RA; The Urban Institute. Challenging the status quo in chronic disease care: seven case studies. California Healthcare Foundation: 2006. California HealthCare Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/C/PDF%20ChallengingStatusQuoCaseStudies.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

35. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, et al. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1817-1825.

36. Schneider ME. Medicare finalizes plan for non-face-to-face payments. Family Practice News Web site. Available at: http://www.familypracticenews.com/?id=2633&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=226457&cHash=2aeafe0585c7156dcf23891d010cd12f. Accessed December 2, 2013.

37. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact sheets: Policy and payment changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2015. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/newsroom/mediareleasedatabase/fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-10-31-7.html. Accessed February 13, 2015.

38. Berry LL, Dunham J. Redefining the patient experience with collaborative care. Harvard Business Review Blog Network. Harvard Business Review Web site. Available at: https://hbr.org/2013/09/redefining-the-patient-experience-with-collaborative-care/. Accessed February 5, 2015.

39. Lyon RK, Slawson J. An organized approach to chronic disease care. Fam Pract Manag. 2011;18:27-31.

1. Institute of Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Web site. Available at http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2015.

2.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503-509.

3. Naylor MD, Coburn KD, Kurtzman ET, et al. Inter-professional team-based primary care for chronically ill adults: State of the science. White paper presented at: the ABIM Foundation meeting to Advance Team-Based Care for the Chronically Ill in Ambulatory Settings; March 24-25, 2010; Philadelphia, PA.

4.Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, et al. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s Retooling for an Aging America report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2328-2337.

5.Kuzel AJ. Keys to high-functioning office teams. Family Practice Management. 2011;18:15-18.

6.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

7. Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The Group Health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:835-843.

8. Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:457-461.

9. Chen EH, Thom DH, Hessler DM, et al. Using the teamlet model to improve chronic care in an academic primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 4):S610-S614.

10. Wasson JH, Anders SG, Moore LG, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 2. Learning from micro practices about providing patients the care they want and need. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:445-452.

11. Williams I, Dickinson H, Robinson S. Clinical microsystems: An evaluation. Health Services Management Centre, School of Public Policy, University of Birmingham, England; 2007. Available at: http://chain.ulcc.ac.uk/chain/documents/hsmc_evaluation_report_CMS2007final.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2015.

12. Willard R, Bodenheimer T. The building blocks of high-performing primary care: Lessons from the field. April 2012. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/B/PDF%20BuildingBlocksPrimaryCare.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569-572.

14. Boult C, Karm L, Groves C. Improving chronic care: the “guided care” model. Perm J. 2008;12:50-54.

15. Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD006560.

16. Bloom FJ, Graf TR, Steele GD. Improved patient outcomes in 3 years with a system of care for diabetes. October 2012. Available at: http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2012/Commentaries/VSRT-Improved-Patient-Outcomes.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Bloom FJ Jr, Yan X, Stewart WF, et al. Primary care diabetes bundle management: 3-year outcomes for microvascular and macrovascular events. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:e175-e182.

18. Pape GA, Hunt JS, Butler KL, et al. Team-based care approach to cholesterol management in diabetes mellitus: two-year cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1480-1486.

19. Scanlon DP, Hollenbeak CS, Beich J, et al. Financial and clinical impact of team-based treatment for medicaid enrollees with diabetes in a federally qualified health center. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2160-2165.

20. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, et al. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD001481.

21. Goldberg GD, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, et al. Team-based care: a critical element of primary care practice transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16:150-156.

22. Lipton HL. Home is where the health is: advancing team-based care in chronic disease management. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1945-1948.

23. Farris KB, Côté I, Feeny D, et al. Enhancing primary care for complex patients. Demonstration project using multidisciplinary teams. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:998-1003.

24. Anderson P, Halley MD. A new approach to making your doctor-nurse team more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

25. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T, Grundy P. The outcomes of implementing patient-centered medical home interventions: A review of the evidence on quality, access and costs from recent prospective evaluation studies, August 2009. Washington, DC; Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2009.

26. Smith M, Giuliano MR, Starkowski MP. In Connecticut: improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:646-654.

27. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;16:955-964.

28. Bray P, Roupe M, Young S, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of system redesign for diabetes care management in rural areas: the eastern North Carolina experience. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31:712-718.

29. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health Partners uses “BestCare” practices to improve care and outcomes, reduce costs. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Web site. Available at http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Documents/IHITripleAimHealthPartnersSummaryofSuccessJul09v2.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

30. Rich MW, Beckman V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190-1195.

31. Domurat ES. Diabetes managed care and clinical outcomes: the Harbor City, California Kaiser Permanente diabetes care system. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:1299-1307.

32. Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:506-514.

33. Liu CF, Hendrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in a primary care veteran population. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:698-704.

34. Berenson RA; The Urban Institute. Challenging the status quo in chronic disease care: seven case studies. California Healthcare Foundation: 2006. California HealthCare Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/C/PDF%20ChallengingStatusQuoCaseStudies.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

35. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, et al. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1817-1825.

36. Schneider ME. Medicare finalizes plan for non-face-to-face payments. Family Practice News Web site. Available at: http://www.familypracticenews.com/?id=2633&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=226457&cHash=2aeafe0585c7156dcf23891d010cd12f. Accessed December 2, 2013.

37. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact sheets: Policy and payment changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2015. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/newsroom/mediareleasedatabase/fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-10-31-7.html. Accessed February 13, 2015.

38. Berry LL, Dunham J. Redefining the patient experience with collaborative care. Harvard Business Review Blog Network. Harvard Business Review Web site. Available at: https://hbr.org/2013/09/redefining-the-patient-experience-with-collaborative-care/. Accessed February 5, 2015.

39. Lyon RK, Slawson J. An organized approach to chronic disease care. Fam Pract Manag. 2011;18:27-31.