User login

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the genital and perianal skin of postmenopausal women. The mean age of onset is the mid- to late 50s; fewer than 15% of lichen sclerosus cases present in children.1,2 Case 1 represents presentation of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a premenopausal woman, which is uncommon.

The classic presentation of lichen sclerosus is a well-defined white, atrophic plaque with a wrinkled surface appearance located on the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin. Less commonly, examination may reveal white papules and macules, pallor with overlying edema, or hyperpigmentation. Loss of labia minora tissue and phimosis of the clitoral hood also are often present in patients with untreated lichen sclerosus.

Additionally, secondary changes, such as erosions, fissuring, and blisters, can be seen on examination. The most frequent symptom associated with lichen sclerosus is intense itching of the affected area. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, dysuria, sexual dysfunction, and bleeding. Occasionally, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic.1 Like other autoimmune conditions, lichen sclerosus may persist indefinitely, highlighting the importance of effective treatment.

How should we evaluate and treat patients with these symptoms?

Perform a skin biopsy and start treatment with very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment daily for at least 6 weeks.

Skin biopsy. Definitive diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is made based on a skin biopsy. Because treatment can impact the interpretation of a skin biopsy, a biopsy is optimally performed prior to treatment initiation.

The patient in Case 1 underwent biopsy of the left labia majora. Results were consistent with early lichen sclerosus. The patient in Case 2 was reluctant to proceed with vulvar biopsy.

A biopsy specimen should be taken from the affected area that is most white in appearance.1

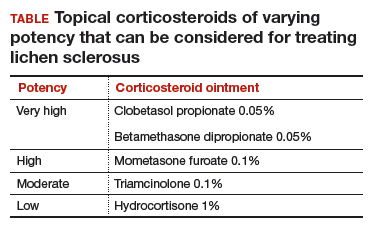

Topical treatment. To induce remission, twice-daily application of very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment to the affected area for at least 6 weeks is recommended. Once the skin color and texture have normalized, the topical corticosteroid strength (and frequency of application) can slowly be reduced to the lowest potency/frequency at which the patient remains in remission. Examples of very high–, high-, moderate-, and low-potency corticosteroid ointments are listed in the TABLE.

Follow-up. Evaluate the patient every 3 months until the topical steroid potency remains stable and the skin appearance is normal.

Treat early, and aggressively, to prevent complications

Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are important in managing this disease process. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, significant scarring and deformation of the vulva can occur.1

Neoplastic transformation of lichen sclerosus into vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma can occur (mean incidence, 2.8%). However, the literature reports significant variability in the incidence, ranging between 0% and 31%.3 Published reports support decreased scarring and future development of malignancies in patients who adhere to treatment recommendations.4

Symptoms resolved

In both cases described here, the patients were treated with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Both women reported complete resolution of pruritus after treatment. As can be seen in the posttreatment photo of the patient described in Case 1, her vulvar inflammation resolved (FIGURE 4).

These cases represent the varied exam findings in patients experiencing vulvar pruritus with early (Case 1) versus more advanced (Case 2) lichen sclerosus. In addition, they underscore that appropriate evaluation and management of lichen sclerosus can produce excellent treatment results.

- Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

- Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180-183.

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061-1067.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the genital and perianal skin of postmenopausal women. The mean age of onset is the mid- to late 50s; fewer than 15% of lichen sclerosus cases present in children.1,2 Case 1 represents presentation of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a premenopausal woman, which is uncommon.

The classic presentation of lichen sclerosus is a well-defined white, atrophic plaque with a wrinkled surface appearance located on the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin. Less commonly, examination may reveal white papules and macules, pallor with overlying edema, or hyperpigmentation. Loss of labia minora tissue and phimosis of the clitoral hood also are often present in patients with untreated lichen sclerosus.

Additionally, secondary changes, such as erosions, fissuring, and blisters, can be seen on examination. The most frequent symptom associated with lichen sclerosus is intense itching of the affected area. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, dysuria, sexual dysfunction, and bleeding. Occasionally, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic.1 Like other autoimmune conditions, lichen sclerosus may persist indefinitely, highlighting the importance of effective treatment.

How should we evaluate and treat patients with these symptoms?

Perform a skin biopsy and start treatment with very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment daily for at least 6 weeks.

Skin biopsy. Definitive diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is made based on a skin biopsy. Because treatment can impact the interpretation of a skin biopsy, a biopsy is optimally performed prior to treatment initiation.

The patient in Case 1 underwent biopsy of the left labia majora. Results were consistent with early lichen sclerosus. The patient in Case 2 was reluctant to proceed with vulvar biopsy.

A biopsy specimen should be taken from the affected area that is most white in appearance.1

Topical treatment. To induce remission, twice-daily application of very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment to the affected area for at least 6 weeks is recommended. Once the skin color and texture have normalized, the topical corticosteroid strength (and frequency of application) can slowly be reduced to the lowest potency/frequency at which the patient remains in remission. Examples of very high–, high-, moderate-, and low-potency corticosteroid ointments are listed in the TABLE.

Follow-up. Evaluate the patient every 3 months until the topical steroid potency remains stable and the skin appearance is normal.

Treat early, and aggressively, to prevent complications

Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are important in managing this disease process. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, significant scarring and deformation of the vulva can occur.1

Neoplastic transformation of lichen sclerosus into vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma can occur (mean incidence, 2.8%). However, the literature reports significant variability in the incidence, ranging between 0% and 31%.3 Published reports support decreased scarring and future development of malignancies in patients who adhere to treatment recommendations.4

Symptoms resolved

In both cases described here, the patients were treated with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Both women reported complete resolution of pruritus after treatment. As can be seen in the posttreatment photo of the patient described in Case 1, her vulvar inflammation resolved (FIGURE 4).

These cases represent the varied exam findings in patients experiencing vulvar pruritus with early (Case 1) versus more advanced (Case 2) lichen sclerosus. In addition, they underscore that appropriate evaluation and management of lichen sclerosus can produce excellent treatment results.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the genital and perianal skin of postmenopausal women. The mean age of onset is the mid- to late 50s; fewer than 15% of lichen sclerosus cases present in children.1,2 Case 1 represents presentation of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a premenopausal woman, which is uncommon.

The classic presentation of lichen sclerosus is a well-defined white, atrophic plaque with a wrinkled surface appearance located on the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin. Less commonly, examination may reveal white papules and macules, pallor with overlying edema, or hyperpigmentation. Loss of labia minora tissue and phimosis of the clitoral hood also are often present in patients with untreated lichen sclerosus.

Additionally, secondary changes, such as erosions, fissuring, and blisters, can be seen on examination. The most frequent symptom associated with lichen sclerosus is intense itching of the affected area. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, dysuria, sexual dysfunction, and bleeding. Occasionally, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic.1 Like other autoimmune conditions, lichen sclerosus may persist indefinitely, highlighting the importance of effective treatment.

How should we evaluate and treat patients with these symptoms?

Perform a skin biopsy and start treatment with very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment daily for at least 6 weeks.

Skin biopsy. Definitive diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is made based on a skin biopsy. Because treatment can impact the interpretation of a skin biopsy, a biopsy is optimally performed prior to treatment initiation.

The patient in Case 1 underwent biopsy of the left labia majora. Results were consistent with early lichen sclerosus. The patient in Case 2 was reluctant to proceed with vulvar biopsy.

A biopsy specimen should be taken from the affected area that is most white in appearance.1

Topical treatment. To induce remission, twice-daily application of very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment to the affected area for at least 6 weeks is recommended. Once the skin color and texture have normalized, the topical corticosteroid strength (and frequency of application) can slowly be reduced to the lowest potency/frequency at which the patient remains in remission. Examples of very high–, high-, moderate-, and low-potency corticosteroid ointments are listed in the TABLE.

Follow-up. Evaluate the patient every 3 months until the topical steroid potency remains stable and the skin appearance is normal.

Treat early, and aggressively, to prevent complications

Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are important in managing this disease process. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, significant scarring and deformation of the vulva can occur.1

Neoplastic transformation of lichen sclerosus into vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma can occur (mean incidence, 2.8%). However, the literature reports significant variability in the incidence, ranging between 0% and 31%.3 Published reports support decreased scarring and future development of malignancies in patients who adhere to treatment recommendations.4

Symptoms resolved

In both cases described here, the patients were treated with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Both women reported complete resolution of pruritus after treatment. As can be seen in the posttreatment photo of the patient described in Case 1, her vulvar inflammation resolved (FIGURE 4).

These cases represent the varied exam findings in patients experiencing vulvar pruritus with early (Case 1) versus more advanced (Case 2) lichen sclerosus. In addition, they underscore that appropriate evaluation and management of lichen sclerosus can produce excellent treatment results.

- Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

- Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180-183.

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061-1067.

- Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

- Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180-183.

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061-1067.

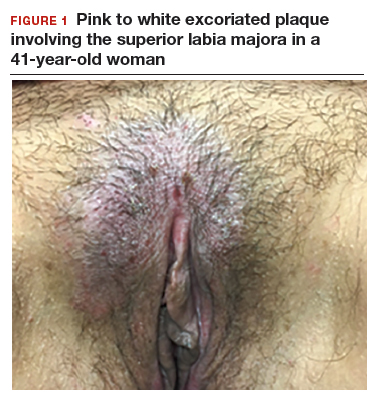

CASE 1: Vulvar pruritus affecting a woman’s quality of life

A 41-year-old premenopausal white woman presented to her gynecologist with intense vulvar pruritus for a 6-month duration, with a recent increase in severity (FIGURE 1). She tried treating it with topical antifungal cream, hydrocortisone ointment, and coconut oil, with no improvement. She noted that the intense itching was interfering with her sleep and marriage. The patient denied having an increase in urinary frequency or urgency, dysuria, hematochezia, or bowel changes.

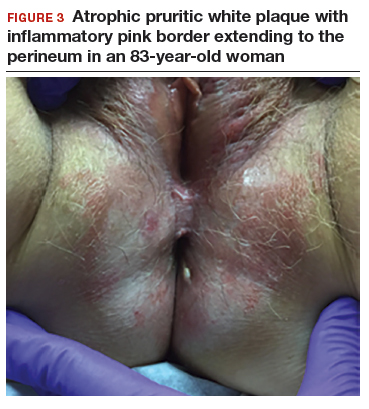

CASE 2: Older woman with long-term persistent genital pruritus

An 83-year-old postmenopausal white woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a regular skin examination. The patient endorsed symptoms of vulvar and perianal pruritus that had persisted for more than 6 months (FIGURES 2 and 3). The genital itching occurred throughout most of the day. The patient previously treated her symptoms with an over-the-counter antifungal cream, which minimally improved the itching.