User login

Despite the success of several US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiatives in facilitating psychosocial functioning, rehabilitation, and re-entry among veterans experiencing homelessness and/or interactions with the criminal justice system (ie, justice-involved veterans), suicide risk among these veterans remains a significant public health concern. Rates of suicide among veterans experiencing homelessness are more than double that of veterans with no history of homelessness.1 Similarly, justice-involved veterans experience myriad mental health concerns, including elevated rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and self-directed violence relative to those with no history of criminal justice involvement.2

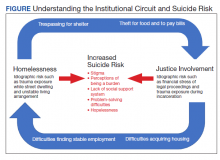

In addition, a bidirectional relationship between criminal justice involvement and homelessness, often called the “institutional circuit,” is well established. Criminal justice involvement can directly result in difficulty finding housing.3 For example, veterans may have their lease agreement denied based solely on their history of criminogenic behavior. Moreover, criminal justice involvement can indirectly impact a veteran’s ability to maintain housing. Indeed, justice-involved veterans can experience difficulty attaining and sustaining employment, which in turn can result in financial difficulties, including inability to afford rental or mortgage payments.

Similarly, those at risk for or experiencing housing instability may resort to criminogenic behavior to survive in the context of limited psychosocial resources.4-6 For instance, a veteran experiencing homelessness may seek refuge from inclement weather in a heated apartment stairwell and subsequently be charged with trespassing. Similarly, these veterans also may resort to theft to eat or pay bills. To this end, homelessness and justice involvement are likely a deleterious cycle that is difficult for the veteran to escape.

Unfortunately, the concurrent impact of housing insecurity and criminal justice involvement often serves to further exacerbate mental health sequelae, including suicide risk (Figure).7 In addition to precipitating frustration and helplessness among veterans who are navigating these stressors, these social determinants of health can engender a perception that the veteran is a burden to those in their support system. For example, these veterans may depend on friends or family to procure housing or transportation assistance for a job, medical appointments, and court hearings.

Furthermore, homelessness and justice involvement can impact veterans’ interpersonal relationships. For instance, veterans with a history of criminal justice involvement may feel stigmatized and ostracized from their social support system. Justice-involved veterans sometimes endorse being labeled an offender, which can result in perceptions that one is poorly perceived by others and generally seen as a bad person.8 In addition, the conditions of a justice-involved veteran’s probation or parole may further exacerbate social relationships. For example, veterans with histories of engaging in intimate partner violence may lose visitation rights with their children, further reinforcing negative views of self and impacting the veterans’ family network.

As such, these homeless and justice-involved veterans may lack a meaningful social support system when navigating psychosocial stressors. Because hopelessness, burdensomeness, and perceptions that one lacks a social support network are potential drivers of suicidal self-directed violence among these populations, facilitating access to and engagement in health (eg, psychotherapy, medication management) and social (eg, case management, transitional housing) services is necessary to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.9

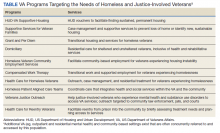

Several VA homeless and justice-related programs have been developed to meet the needs of these veterans (Table). Such programs offer direct access to health and social services capable of addressing mental health symptoms and suicide risk. Moreover, these programs support veterans at various intercepts, or points at which there is an opportunity to identify those at elevated risk and provide access to evidence-based care. For instance, VA homeless programs exist tailored toward those currently, or at risk for, experiencing homelessness. Additionally, VA justice-related programs can target intercepts prior to jail or prison, such as working with crisis intervention teams or diversion courts as well as intercepts following release, such as providing services to facilitate postincarceration reentry. Even VA programs that do not directly administer mental health intervention (eg, Grant and Per Diem, Veterans Justice Outreach) serve as critical points of contact that can connect these veterans to evidence-based suicide prevention treatments (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention; pharmacotherapy) in the VA or the community.

Within these programs, several suicide prevention efforts also are currently underway. In particular, the VA has mandated routine screening for suicide risk. This includes screening for the presence of elevations in acute risk (eg, suicidal intent, recent suicide attempt) and, within the context of acute risk, conducting a comprehensive risk evaluation that captures veterans’ risk and protective factors as well as access to lethal means. These clinical data are used to determine the veteran’s severity of acute and chronic risk and match them to an appropriate intervention.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several gaps in understanding exist, such as for example, elucidating the potential role of traditional VA homeless and justice-related programming in reducing risk for suicide.10 Additional research specific to suicide prevention programming among these populations also remains important.11 In particular, no examination to date has evaluated national rates of suicide risk assessment within these settings or elucidated if specific subsets of homeless and justice-involved veterans may be less likely to receive suicide risk screening. For instance, understanding whether homeless veterans accessing mental health services are more likely to be screened for suicide risk relative to homeless veterans accessing care in other VA settings (eg, emergency services). Moreover, the effectiveness of existing suicide-focused evidence-based treatments among homeless and justice-involved veterans remains unknown. Such research may reveal a need to adapt existing interventions, such as safety planning, to the idiographic needs of homeless or justice-involved veterans in order to improve effectiveness.10 Finally, social determinants of health, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and rurality may confer additional risk coupled with difficulties accessing and engaging in care within these populations.11 As such, research specific to these veteran populations and their inherent suicide prevention needs may further inform suicide prevention efforts.

Despite these gaps, it is important to acknowledge ongoing research and programmatic efforts focused on enhancing mental health and suicide prevention practices within VA settings. For example, efforts led by Temblique and colleagues acknowledge not only challenges to the execution of suicide prevention efforts in VA homeless programs, but also potential methods of enhancing care, including additional training in suicide risk screening and evaluation due to provider discomfort.12 Such quality improvement projects are paramount in their potential to identify gaps in health service delivery and thus potentially save veteran lives.

The VA currently has several programs focused on enhancing care for homeless and justice-involved veterans, and many incorporate suicide prevention initiatives. Further understanding of factors that may impact health service delivery of suicide risk assessment and intervention among these populations may be beneficial in order to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.

1. McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

2. Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):730-739. doi:10.1037/tra0001038

3. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

4. Fischer PJ. Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):46-51. doi:10.1176/ps.39.1.46

5. McCarthy B, Hagan J. Homelessness: a criminogenic situation? Br J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393–410.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048137

6. Solomon P, Draine J. Issues in serving the forensic client. Soc Work. 1995;40(1):25-33.

7. Holliday R, Forster JE, Desai A, et al. Association of lifetime homelessness and justice involvement with psychiatric symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.007

8. Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

9. Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2021;30(1):41-49. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

10. Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

11. Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 2):S103-S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399.

12. Temblique EKR, Foster K, Fujimoto J, Kopelson K, Borthick KM, et al. Addressing the mental health crisis: a one year review of a nationally-led intervention to improve suicide prevention screening at a large homeless veterans clinic. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):12-18. doi:10.12788/fp.0215

Despite the success of several US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiatives in facilitating psychosocial functioning, rehabilitation, and re-entry among veterans experiencing homelessness and/or interactions with the criminal justice system (ie, justice-involved veterans), suicide risk among these veterans remains a significant public health concern. Rates of suicide among veterans experiencing homelessness are more than double that of veterans with no history of homelessness.1 Similarly, justice-involved veterans experience myriad mental health concerns, including elevated rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and self-directed violence relative to those with no history of criminal justice involvement.2

In addition, a bidirectional relationship between criminal justice involvement and homelessness, often called the “institutional circuit,” is well established. Criminal justice involvement can directly result in difficulty finding housing.3 For example, veterans may have their lease agreement denied based solely on their history of criminogenic behavior. Moreover, criminal justice involvement can indirectly impact a veteran’s ability to maintain housing. Indeed, justice-involved veterans can experience difficulty attaining and sustaining employment, which in turn can result in financial difficulties, including inability to afford rental or mortgage payments.

Similarly, those at risk for or experiencing housing instability may resort to criminogenic behavior to survive in the context of limited psychosocial resources.4-6 For instance, a veteran experiencing homelessness may seek refuge from inclement weather in a heated apartment stairwell and subsequently be charged with trespassing. Similarly, these veterans also may resort to theft to eat or pay bills. To this end, homelessness and justice involvement are likely a deleterious cycle that is difficult for the veteran to escape.

Unfortunately, the concurrent impact of housing insecurity and criminal justice involvement often serves to further exacerbate mental health sequelae, including suicide risk (Figure).7 In addition to precipitating frustration and helplessness among veterans who are navigating these stressors, these social determinants of health can engender a perception that the veteran is a burden to those in their support system. For example, these veterans may depend on friends or family to procure housing or transportation assistance for a job, medical appointments, and court hearings.

Furthermore, homelessness and justice involvement can impact veterans’ interpersonal relationships. For instance, veterans with a history of criminal justice involvement may feel stigmatized and ostracized from their social support system. Justice-involved veterans sometimes endorse being labeled an offender, which can result in perceptions that one is poorly perceived by others and generally seen as a bad person.8 In addition, the conditions of a justice-involved veteran’s probation or parole may further exacerbate social relationships. For example, veterans with histories of engaging in intimate partner violence may lose visitation rights with their children, further reinforcing negative views of self and impacting the veterans’ family network.

As such, these homeless and justice-involved veterans may lack a meaningful social support system when navigating psychosocial stressors. Because hopelessness, burdensomeness, and perceptions that one lacks a social support network are potential drivers of suicidal self-directed violence among these populations, facilitating access to and engagement in health (eg, psychotherapy, medication management) and social (eg, case management, transitional housing) services is necessary to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.9

Several VA homeless and justice-related programs have been developed to meet the needs of these veterans (Table). Such programs offer direct access to health and social services capable of addressing mental health symptoms and suicide risk. Moreover, these programs support veterans at various intercepts, or points at which there is an opportunity to identify those at elevated risk and provide access to evidence-based care. For instance, VA homeless programs exist tailored toward those currently, or at risk for, experiencing homelessness. Additionally, VA justice-related programs can target intercepts prior to jail or prison, such as working with crisis intervention teams or diversion courts as well as intercepts following release, such as providing services to facilitate postincarceration reentry. Even VA programs that do not directly administer mental health intervention (eg, Grant and Per Diem, Veterans Justice Outreach) serve as critical points of contact that can connect these veterans to evidence-based suicide prevention treatments (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention; pharmacotherapy) in the VA or the community.

Within these programs, several suicide prevention efforts also are currently underway. In particular, the VA has mandated routine screening for suicide risk. This includes screening for the presence of elevations in acute risk (eg, suicidal intent, recent suicide attempt) and, within the context of acute risk, conducting a comprehensive risk evaluation that captures veterans’ risk and protective factors as well as access to lethal means. These clinical data are used to determine the veteran’s severity of acute and chronic risk and match them to an appropriate intervention.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several gaps in understanding exist, such as for example, elucidating the potential role of traditional VA homeless and justice-related programming in reducing risk for suicide.10 Additional research specific to suicide prevention programming among these populations also remains important.11 In particular, no examination to date has evaluated national rates of suicide risk assessment within these settings or elucidated if specific subsets of homeless and justice-involved veterans may be less likely to receive suicide risk screening. For instance, understanding whether homeless veterans accessing mental health services are more likely to be screened for suicide risk relative to homeless veterans accessing care in other VA settings (eg, emergency services). Moreover, the effectiveness of existing suicide-focused evidence-based treatments among homeless and justice-involved veterans remains unknown. Such research may reveal a need to adapt existing interventions, such as safety planning, to the idiographic needs of homeless or justice-involved veterans in order to improve effectiveness.10 Finally, social determinants of health, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and rurality may confer additional risk coupled with difficulties accessing and engaging in care within these populations.11 As such, research specific to these veteran populations and their inherent suicide prevention needs may further inform suicide prevention efforts.

Despite these gaps, it is important to acknowledge ongoing research and programmatic efforts focused on enhancing mental health and suicide prevention practices within VA settings. For example, efforts led by Temblique and colleagues acknowledge not only challenges to the execution of suicide prevention efforts in VA homeless programs, but also potential methods of enhancing care, including additional training in suicide risk screening and evaluation due to provider discomfort.12 Such quality improvement projects are paramount in their potential to identify gaps in health service delivery and thus potentially save veteran lives.

The VA currently has several programs focused on enhancing care for homeless and justice-involved veterans, and many incorporate suicide prevention initiatives. Further understanding of factors that may impact health service delivery of suicide risk assessment and intervention among these populations may be beneficial in order to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.

Despite the success of several US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiatives in facilitating psychosocial functioning, rehabilitation, and re-entry among veterans experiencing homelessness and/or interactions with the criminal justice system (ie, justice-involved veterans), suicide risk among these veterans remains a significant public health concern. Rates of suicide among veterans experiencing homelessness are more than double that of veterans with no history of homelessness.1 Similarly, justice-involved veterans experience myriad mental health concerns, including elevated rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and self-directed violence relative to those with no history of criminal justice involvement.2

In addition, a bidirectional relationship between criminal justice involvement and homelessness, often called the “institutional circuit,” is well established. Criminal justice involvement can directly result in difficulty finding housing.3 For example, veterans may have their lease agreement denied based solely on their history of criminogenic behavior. Moreover, criminal justice involvement can indirectly impact a veteran’s ability to maintain housing. Indeed, justice-involved veterans can experience difficulty attaining and sustaining employment, which in turn can result in financial difficulties, including inability to afford rental or mortgage payments.

Similarly, those at risk for or experiencing housing instability may resort to criminogenic behavior to survive in the context of limited psychosocial resources.4-6 For instance, a veteran experiencing homelessness may seek refuge from inclement weather in a heated apartment stairwell and subsequently be charged with trespassing. Similarly, these veterans also may resort to theft to eat or pay bills. To this end, homelessness and justice involvement are likely a deleterious cycle that is difficult for the veteran to escape.

Unfortunately, the concurrent impact of housing insecurity and criminal justice involvement often serves to further exacerbate mental health sequelae, including suicide risk (Figure).7 In addition to precipitating frustration and helplessness among veterans who are navigating these stressors, these social determinants of health can engender a perception that the veteran is a burden to those in their support system. For example, these veterans may depend on friends or family to procure housing or transportation assistance for a job, medical appointments, and court hearings.

Furthermore, homelessness and justice involvement can impact veterans’ interpersonal relationships. For instance, veterans with a history of criminal justice involvement may feel stigmatized and ostracized from their social support system. Justice-involved veterans sometimes endorse being labeled an offender, which can result in perceptions that one is poorly perceived by others and generally seen as a bad person.8 In addition, the conditions of a justice-involved veteran’s probation or parole may further exacerbate social relationships. For example, veterans with histories of engaging in intimate partner violence may lose visitation rights with their children, further reinforcing negative views of self and impacting the veterans’ family network.

As such, these homeless and justice-involved veterans may lack a meaningful social support system when navigating psychosocial stressors. Because hopelessness, burdensomeness, and perceptions that one lacks a social support network are potential drivers of suicidal self-directed violence among these populations, facilitating access to and engagement in health (eg, psychotherapy, medication management) and social (eg, case management, transitional housing) services is necessary to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.9

Several VA homeless and justice-related programs have been developed to meet the needs of these veterans (Table). Such programs offer direct access to health and social services capable of addressing mental health symptoms and suicide risk. Moreover, these programs support veterans at various intercepts, or points at which there is an opportunity to identify those at elevated risk and provide access to evidence-based care. For instance, VA homeless programs exist tailored toward those currently, or at risk for, experiencing homelessness. Additionally, VA justice-related programs can target intercepts prior to jail or prison, such as working with crisis intervention teams or diversion courts as well as intercepts following release, such as providing services to facilitate postincarceration reentry. Even VA programs that do not directly administer mental health intervention (eg, Grant and Per Diem, Veterans Justice Outreach) serve as critical points of contact that can connect these veterans to evidence-based suicide prevention treatments (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention; pharmacotherapy) in the VA or the community.

Within these programs, several suicide prevention efforts also are currently underway. In particular, the VA has mandated routine screening for suicide risk. This includes screening for the presence of elevations in acute risk (eg, suicidal intent, recent suicide attempt) and, within the context of acute risk, conducting a comprehensive risk evaluation that captures veterans’ risk and protective factors as well as access to lethal means. These clinical data are used to determine the veteran’s severity of acute and chronic risk and match them to an appropriate intervention.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several gaps in understanding exist, such as for example, elucidating the potential role of traditional VA homeless and justice-related programming in reducing risk for suicide.10 Additional research specific to suicide prevention programming among these populations also remains important.11 In particular, no examination to date has evaluated national rates of suicide risk assessment within these settings or elucidated if specific subsets of homeless and justice-involved veterans may be less likely to receive suicide risk screening. For instance, understanding whether homeless veterans accessing mental health services are more likely to be screened for suicide risk relative to homeless veterans accessing care in other VA settings (eg, emergency services). Moreover, the effectiveness of existing suicide-focused evidence-based treatments among homeless and justice-involved veterans remains unknown. Such research may reveal a need to adapt existing interventions, such as safety planning, to the idiographic needs of homeless or justice-involved veterans in order to improve effectiveness.10 Finally, social determinants of health, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and rurality may confer additional risk coupled with difficulties accessing and engaging in care within these populations.11 As such, research specific to these veteran populations and their inherent suicide prevention needs may further inform suicide prevention efforts.

Despite these gaps, it is important to acknowledge ongoing research and programmatic efforts focused on enhancing mental health and suicide prevention practices within VA settings. For example, efforts led by Temblique and colleagues acknowledge not only challenges to the execution of suicide prevention efforts in VA homeless programs, but also potential methods of enhancing care, including additional training in suicide risk screening and evaluation due to provider discomfort.12 Such quality improvement projects are paramount in their potential to identify gaps in health service delivery and thus potentially save veteran lives.

The VA currently has several programs focused on enhancing care for homeless and justice-involved veterans, and many incorporate suicide prevention initiatives. Further understanding of factors that may impact health service delivery of suicide risk assessment and intervention among these populations may be beneficial in order to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.

1. McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

2. Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):730-739. doi:10.1037/tra0001038

3. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

4. Fischer PJ. Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):46-51. doi:10.1176/ps.39.1.46

5. McCarthy B, Hagan J. Homelessness: a criminogenic situation? Br J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393–410.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048137

6. Solomon P, Draine J. Issues in serving the forensic client. Soc Work. 1995;40(1):25-33.

7. Holliday R, Forster JE, Desai A, et al. Association of lifetime homelessness and justice involvement with psychiatric symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.007

8. Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

9. Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2021;30(1):41-49. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

10. Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

11. Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 2):S103-S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399.

12. Temblique EKR, Foster K, Fujimoto J, Kopelson K, Borthick KM, et al. Addressing the mental health crisis: a one year review of a nationally-led intervention to improve suicide prevention screening at a large homeless veterans clinic. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):12-18. doi:10.12788/fp.0215

1. McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

2. Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):730-739. doi:10.1037/tra0001038

3. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

4. Fischer PJ. Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):46-51. doi:10.1176/ps.39.1.46

5. McCarthy B, Hagan J. Homelessness: a criminogenic situation? Br J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393–410.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048137

6. Solomon P, Draine J. Issues in serving the forensic client. Soc Work. 1995;40(1):25-33.

7. Holliday R, Forster JE, Desai A, et al. Association of lifetime homelessness and justice involvement with psychiatric symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.007

8. Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

9. Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2021;30(1):41-49. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

10. Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

11. Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 2):S103-S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399.

12. Temblique EKR, Foster K, Fujimoto J, Kopelson K, Borthick KM, et al. Addressing the mental health crisis: a one year review of a nationally-led intervention to improve suicide prevention screening at a large homeless veterans clinic. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):12-18. doi:10.12788/fp.0215