User login

Impact of Expanded Eligibility for Veterans With Other Than Honorable Discharges on Treatment Courts and VA Mental Health Care

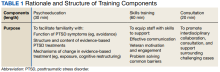

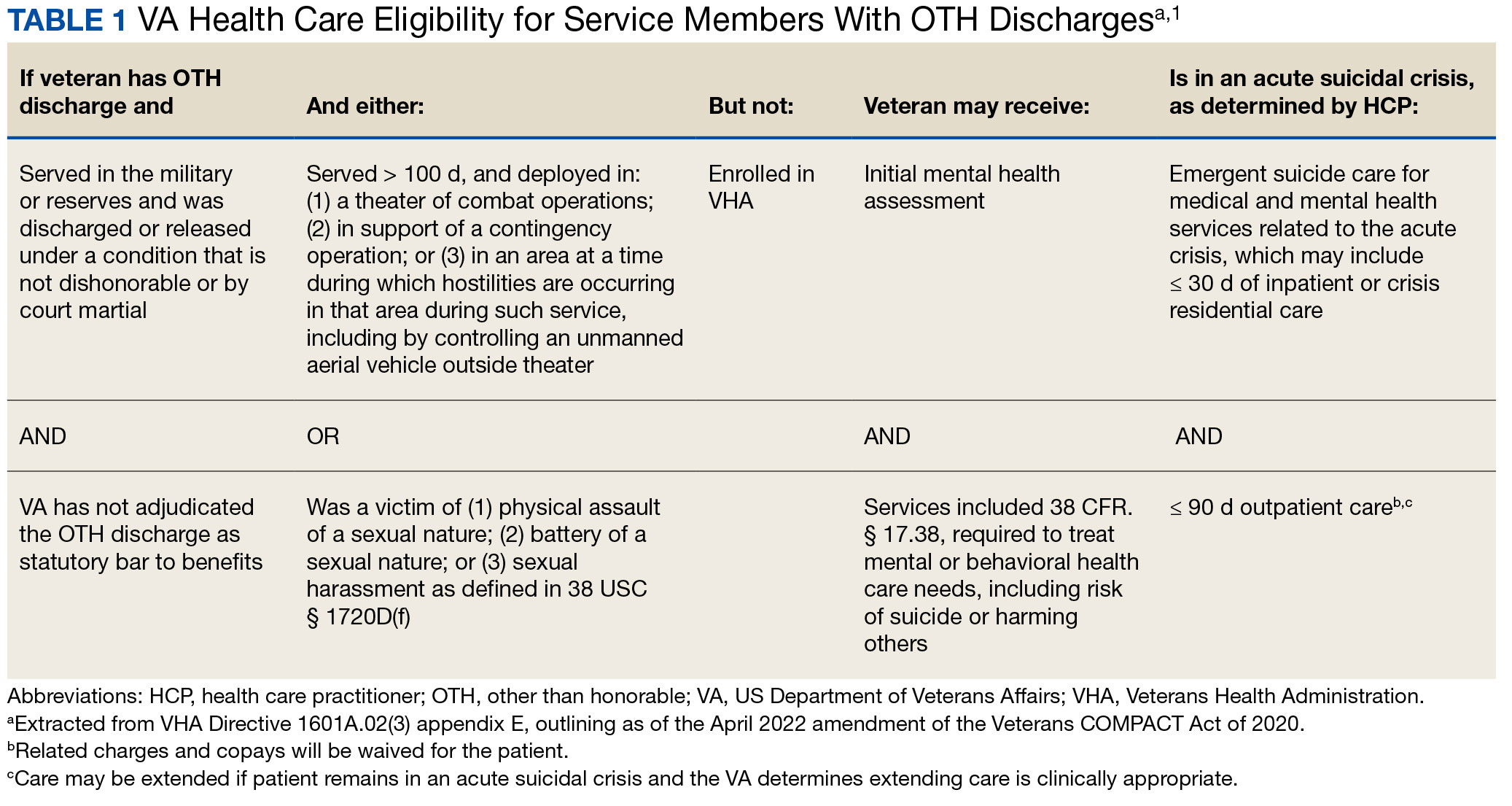

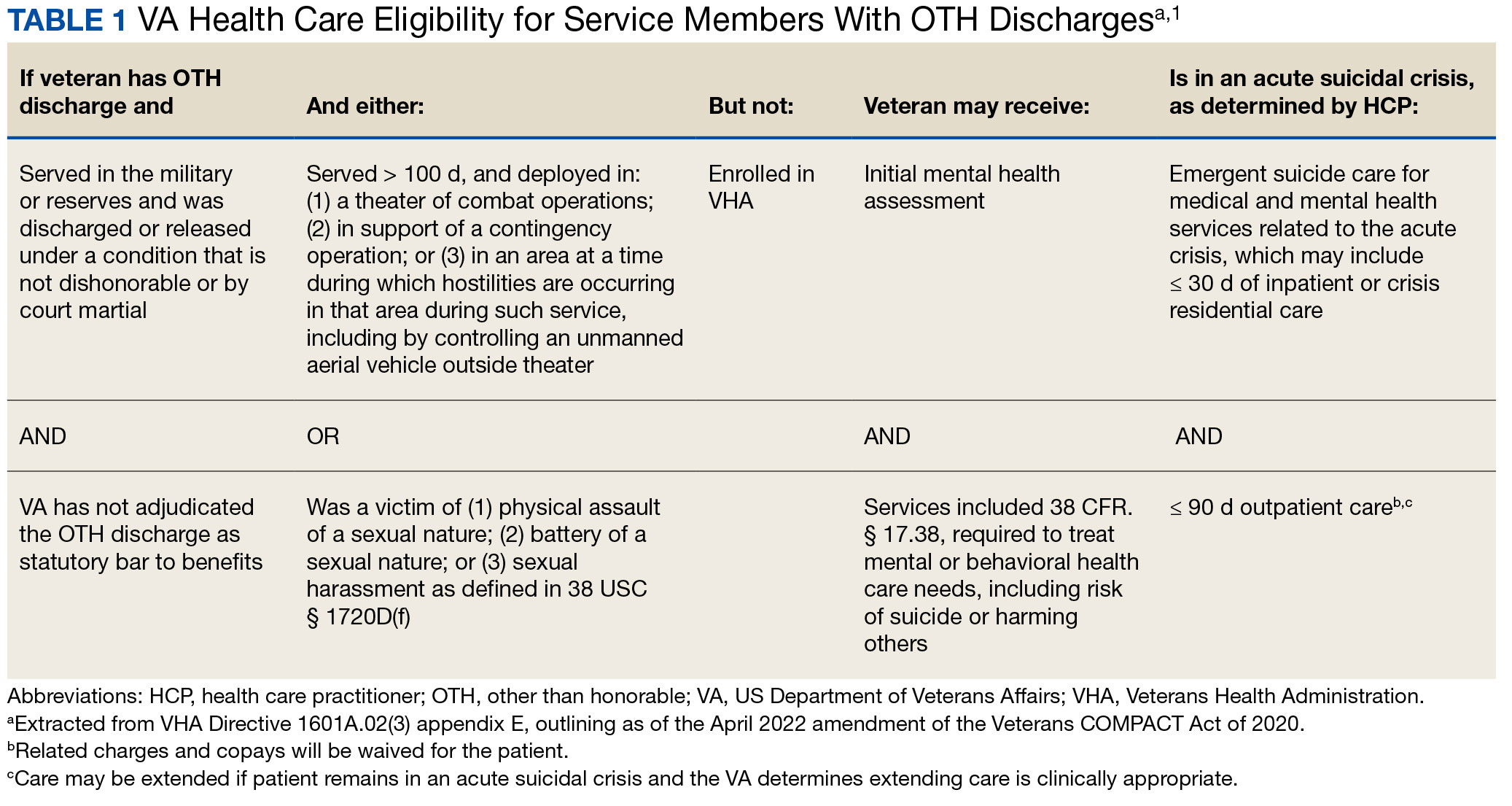

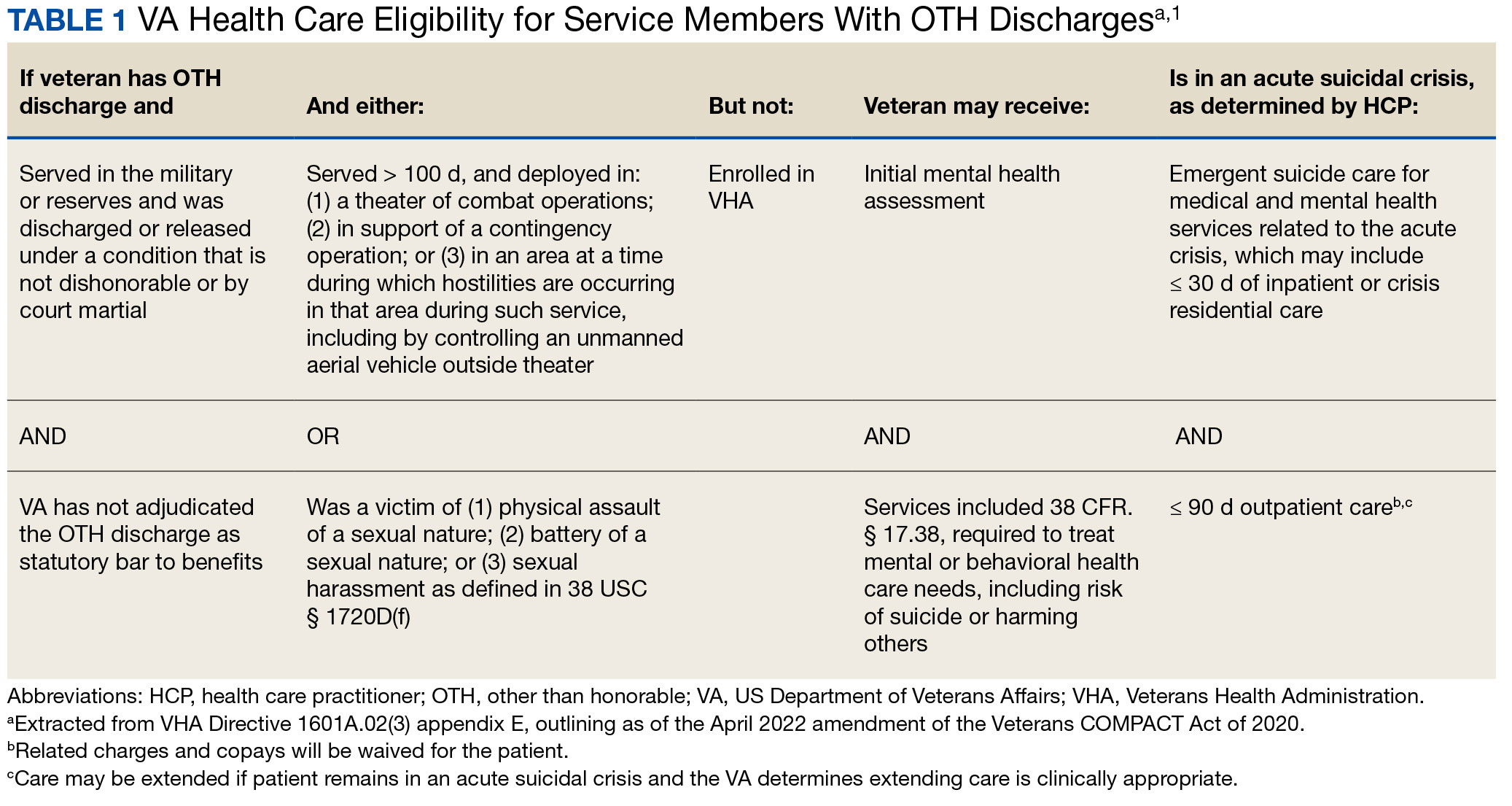

In April 2022, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) revised its behavioral health care eligibility policies to provide comprehensive mental and behavioral health care to former service members who received an Other Than Honorable (OTH) discharge characterization upon separation from military service.1 This policy shift represents a marked expansion in eligibility practices (Table 1 includes amended eligibility criteria).

Since June 2017, eligibility policies allowed veterans with OTH discharges to receive “emergent mental health services” needed to stabilize acute mental health crises related to military service (eg, acute escalations in suicide risk).2,3 Previously, veterans with OTH discharges were largely ineligible for VA-based health care; these individuals were only able to access Veterans Health Administration (VHA) mental and behavioral health care through limited channels of eligibility (eg, for treatment of military sexual trauma or psychosis or other mental illness within 2 years of discharge).4,5 The impetus for expansions in eligibility stemmed from VA efforts to reduce the suicide rate among veterans.6-8 Implications of such expansion extend beyond suicide prevention efforts, with notable promised effects on the care of veterans with criminal-legal involvement. This article highlights potential effects of recent eligibility expansions on veterans with criminal-legal involvement and makes specific recommendations for agencies and organizations serving these veterans.

OTHER THAN HONORABLE DISCHARGE

The US Department of Defense delineates 6 discharge characterizations provided to service members upon separation from military service: honorable, general under honorable conditions, OTH, bad conduct, dishonorable, and uncharacterized. Honorable discharge characterizations are considered to reflect general concordance between service member behavior and military standards; general discharge characterizations reflect some disparity between the service member’s behavior and military standards; OTH, bad conduct, and dishonorable discharge characterizations reflect serious disparities between the service member’s behavior and military standards; and uncharacterized discharge characterizations are given when other discharge characterizations are deemed inappropriate.9,10 OTH discharge characterizations are typically issued under instances of misconduct, fraudulent entry, security reasons, or in lieu of trial by court martial.9,10

Recent research suggests that about 85% of service members receive an honorable discharge characterization upon separation from military service, 8% receive general, 6% receive OTH, and 1% receive bad conduct or dishonorable discharges.11 In 2017, the VA estimated there were > 500,000 prior service members with OTH discharge characterizations, which has grown over time (1.9% during the Korean Conflict, 2.5% during the Vietnam War Era, 3.9% during the Cold War, 4.8% in the Persian Gulf War, and 5.8% in the post-9/11 era).7,11

The OTH discharge characterization is 1 of 3 less than honorable discharges informally referred to as bad papers (ie, OTH, bad conduct, or dishonorable). Former service members receiving these discharge characterizations face significant social stigma and structural discrimination upon military discharge, including significant hurdles to employment and educational pursuits as well as notable social alienation.12 Due to their discharge characterization, some are viewed as less deserving of the veteran title, and until recently, many did not qualify for the complex legal definition of veteran as established by the Congress.11,13 Veterans with OTH discharge characterizations have also historically been excluded from services (eg, VHA care),3 benefits (eg, disability compensation),14 and protections (eg, Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act)15 offered to veterans with honorable or general discharge characterizations. However, eligibility policies have gradually expanded, providing veterans with OTH discharges with access to VHA-based mental and behavioral health services and VA supportive housing assistance.1,3,16

Perhaps due to their historical exclusion from VA services, there is limited research available on the behavioral health and associated needs of veterans with OTH discharges. Some scholars argue that historical exclusions have exacerbated underlying difficulties faced by this population, thereby contributing to stark health and social disparities across discharge types.14,15,17 Studies with large veteran samples, for example, reflect notable demographic and behavioral health differences across discharge types. Compared to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are significantly more likely to be younger, have lower income, use substances, have a history of criminal-legal involvement, and have mental and physical health difficulties.18,19

Substantial evidence also suggests a historical racial bias, with service members of color being disproportionately more likely to receive an OTH discharge.12 Similarly, across all branches of military service, Black service members are significantly more likely to face general or special court martial in military justice proceedings when compared with White service members.20 Service members from gender and sexual minorities are also disproportionately impacted by the OTH designation. Historically, many have been discharged with bad papers due to discriminatory policies, such as Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, which discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation between December 1993 and September 2011, and Directive-type Memorandum-19-004, which banned transgender persons from military service between April 2019 and January 2021.21,22

There is also significant mental health bias in the provision of OTH discharges, such that OTH characterizations are disproportionately represented among individuals with mental health disorders.18-20 Veterans discharged from military service due to behavioral misconduct are significantly more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for various behavioral health conditions and to experience homelessness, criminal-legal involvement, and suicidal ideation and behavior compared with routinely-discharged veterans.23-28

Consistent with their comparatively higher rates of criminal-legal involvement relative to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are disproportionately represented in criminal justice settings. While veterans with OTH discharges represent only 6% of discharging service members and 2.5% of community-based veterans, they represent 10% of incarcerated veterans.11,18,23,29 Preliminary research suggests veterans with OTH discharges may be at higher risk for lifetime incarceration, though the association between OTH discharge and frequency of lifetime arrests remains unclear.18,30

VETERANS TREATMENT COURTS

Given the overrepresentation of veterans with OTH discharges in criminal-legal settings, consideration for this subset of the veteran population and its unique needs is commonplace among problem-solving courts that service veterans. First conceptualized in 2004, Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs) are specialized problem-solving courts that divert veterans away from traditional judicial court and penal systems and into community-based supervision and treatment (most commonly behavioral health services).31-34 Although each VTC program is unique in structure, policies, and procedures, most VTCs can be characterized by certain key elements, including voluntary participation, plea requirements, delayed sentencing (often including reduced or dismissed charges), integration of military culture into court proceedings, a rehabilitative vs adversarial approach to decreasing risk of future criminal behavior, mandated treatment and supervision during participation, and use of veteran mentors to provide peer support.32-35 Eligibility requirements vary; however, many restrict participation to veterans with honorable discharge types and charges for nonviolent offenses.32,33,35-37

VTCs connect veterans within the criminal-legal system to needed behavioral health, community, and social services.31-33,37 VTC participants are commonly connected to case management, behavioral health care, therapeutic journaling programs, and vocational rehabilitation.38,39 Accordingly, the most common difficulties faced by veterans participating in these courts include substance use, mental health, family issues, anger management and/or aggressive behavior, and homelessness.36,39 There is limited research on the effectiveness of VTCs. Evidence on their overall effectiveness is largely mixed, though some studies suggest VTC graduates tend to have lower recidivism rates than offenders more broadly or persons who terminate VTC programs prior to completion.40,41 Other studies suggest that VTC participants are more likely to have jail sanctions, new arrests, and new incarcerations relative to nontreatment court participants.42 Notably, experimental designs (considered the gold standard in assessing effectiveness) to date have not been applied to evaluate the effectiveness of VTCs; as such, the effectiveness of these programs remains an area in need of continued empirical investigation.

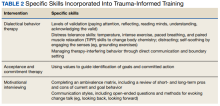

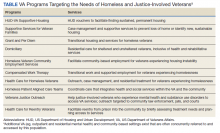

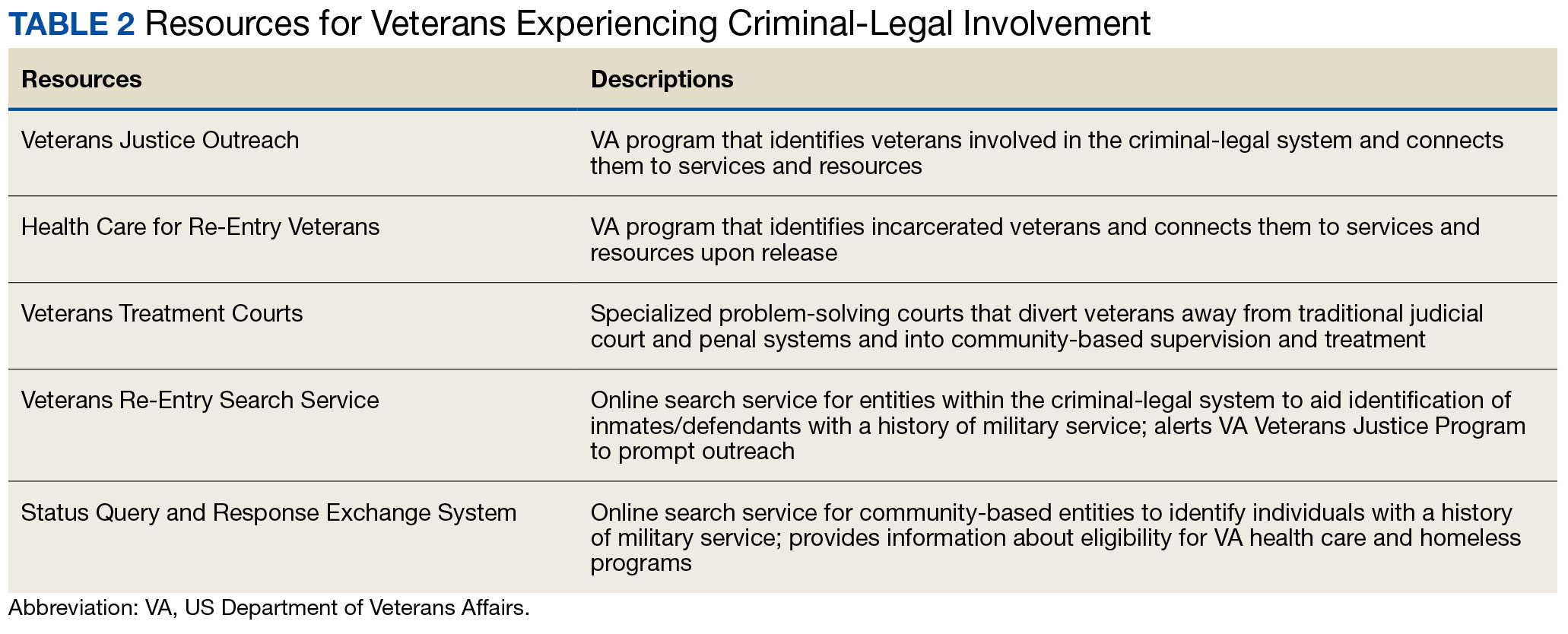

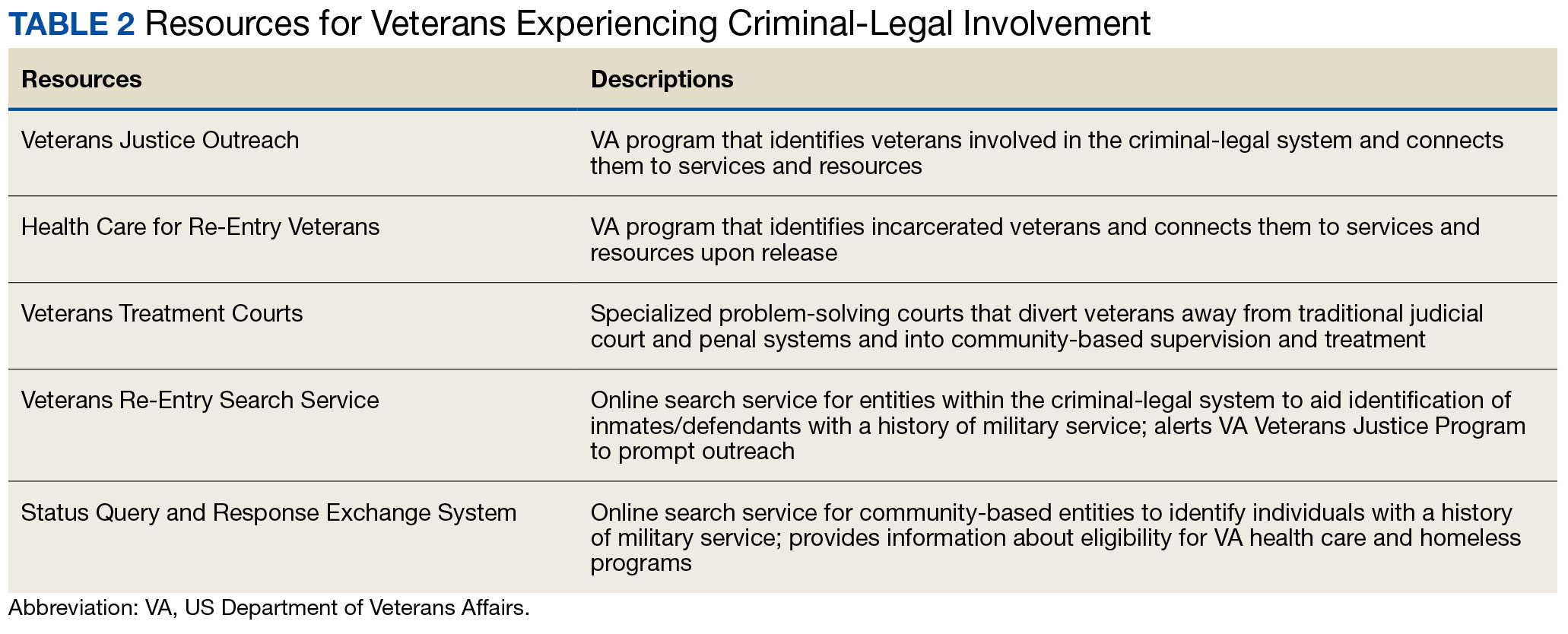

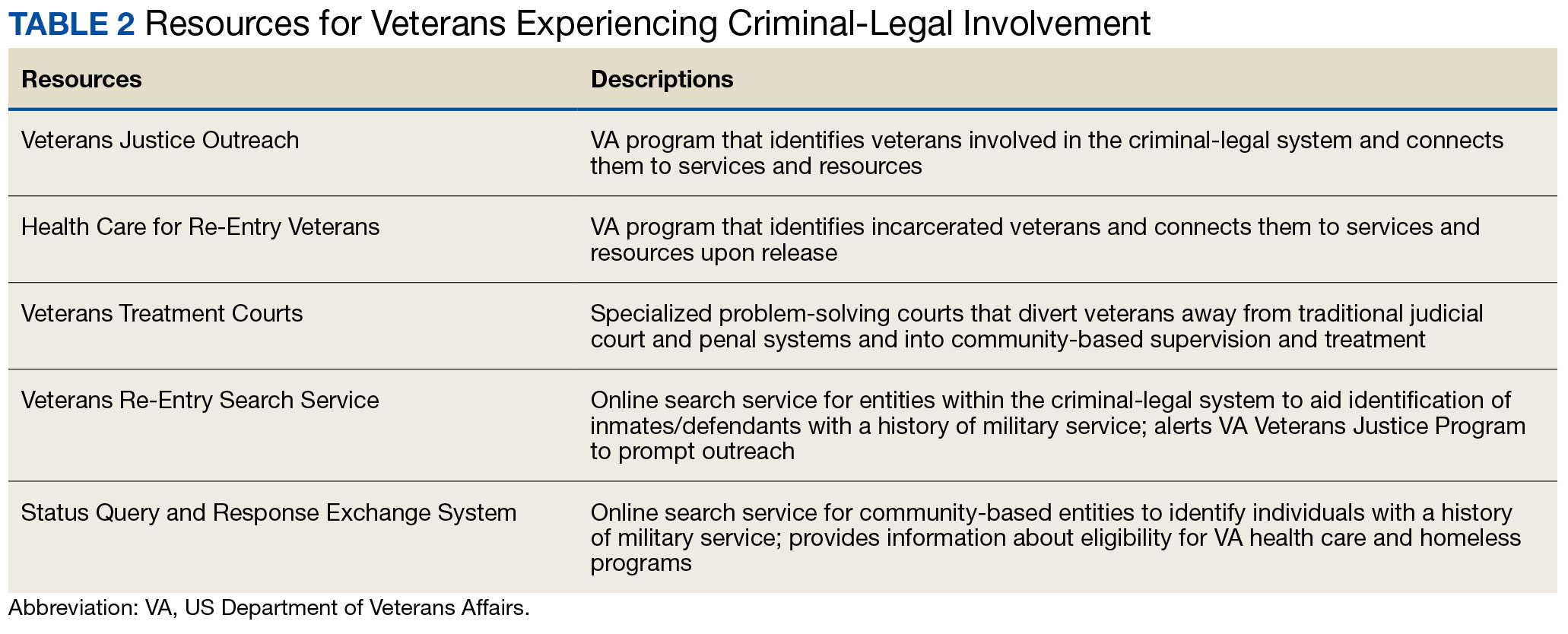

Like all problem-solving courts, VTCs occasionally struggle to connect participating defendants with appropriate care, particularly when encountering structural barriers (eg, insurance, transportation) and/or complex behavioral health needs (eg, personality disorders).34,43 As suicide rates among veterans experiencing criminal-legal involvement surge (about 150 per 100,000 in 2021, a 10% increase from 2020 to 2021 compared to about 40 per 100,000 and a 1.8% increase among other veterans), efficiency of adequate care coordination is vital.44 Many VTCs rely on VTC-VA partnerships and collaborations to navigate these difficulties and facilitate connection of participating veterans to needed services.32-34,45 For example, within the VHA, Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-Entry Veterans (HCRV) specialists assist and bridge the gap between the criminal-legal system (including, but not limited to VTCs) and VA services by engaging veterans involved in the criminal-legal system and connecting them to needed VA-based services (Table 2). Generally, VJO specialists support veterans involved with the front end of the criminallegal system (eg, arrest, pretrial incarceration, or participation in VTCs), while HCRV specialists tend to support veterans transitioning back into the community after a period of incarceration.46,47 Specific to VTCs, VJO specialists typically serve as liaisons between the courts and VA, coordinating VA services for defendants to fulfill their terms of VTC participation.46

The historical exclusion of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations from VA-based services has restricted many from accessing VTC programs.32 Of 17 VTC programs active in Pennsylvania in 2014, only 5 accepted veterans with OTstayH discharges, and 3 required application to and eligibility for VA benefits.33 Similarly, in national surveys of VTC programs, about 1 in 3 report excluding veterans deemed ineligible for VA services.35,36 When veterans with OTH discharges have accessed VTC programs, they have historically relied on non-VA, community-based programming to fulfill treatment mandates, which may be less suited to addressing the unique needs of veterans.48

Veterans who utilize VTCs receive several benefits, namely peer support and mentorship, acceptance into a veteran-centric space, and connection with specially trained staff capable of supporting the veteran through applications for a range of VA benefits (eg, service connection, housing support).31-33,37 Given the disparate prevalence of OTH discharge characterizations among service members from racial, sexual, and gender minorities and among service members with mental health disorders, exclusion of veterans with OTH discharges from VTCs solely based on the type of discharge likely contributes to structural inequities among these already underserved groups by restricting access to these potential benefits. Such structural inequity stands in direct conflict with VTC best practice standards, which admonish programs to adjust eligibility requirements to facilitate access to treatment court programs for historically marginalized groups.49

ELIGIBILITY EXPANSIONS

Given the overrepresentation of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations within the criminal-legal system and historical barriers of these veterans to access needed mental and behavioral health care, expansions in VA eligibility policies could have immense implications for VTCs. First, these expansions could mitigate common barriers to connecting VTC-participating veterans with OTH discharges with needed behavioral health care by allowing these veterans to access established, VA-based services and programming. Expansion may also allow VTCs to serve as a key intercept point for identifying and engaging veterans with OTH discharges who may be unaware of their eligibility for VA-based behavioral health care.

Access to VA health care services is a major resource for VTC participants and a common requirement.32 Eligibility expansion should ease access barriers veterans with OTH discharges commonly face. By providing a potential source of treatment, expansions may also support OTH eligibility practices within VTCs, particularly practices that require participants to be eligible for VA health care.33,35,36 Some VTCs may continue to determine eligibility on the basis of discharge status and remain inaccessible to veterans with OTH discharge characterizations without program-level policy changes.32,36,37

Communicating changes in eligibility policies relevant to veterans with OTH discharges may be a challenge, because many of these individuals have no established channels of communication with the VA. Because veterans with OTH discharges are at increased risk for legal system involvement, VTCs may serve as a unique point of contact to help facilitate communication.18 For example, upon referral to a VTC, veterans with OTH discharges can be identified, VA health care eligibility can be verified, and veterans can connect to VA staff to facilitate enrollment in VA services and care.

VJO specialists are in a favorable position to serve a critical role in utilizing VTCs as a potential intercept point for engaging veterans with OTH discharge characterizations. As outlined in the STRONG Veterans Act of 2022, VJOs are mandated to “spread awareness and understanding of veteran eligibility for the [VJO] Program, including the eligibility of veterans who were discharged from service in the Armed Forces under conditions other than honorable.”50 The Act further requires VJOs to be annually trained in communicating eligibility changes as they arise. Accordingly, VJOs receive ongoing training in a wide variety of critical outreach topics, including changes in eligibility; while VJOs cannot make eligibility determinations, they are tasked with enrolling all veterans involved in the criminal-legal system with whom they interact into VHA services, whether through typical or special eligibility criteria (M. Stimmel, PhD, National Training Director for Veteran Justice Programming, oral communication, July 14, 2023). VJOs therefore routinely serve in this capacity of facilitating VA enrollment of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations.

Recommendations to Veteran-Servicing Judicial Programs

Considering these potential implications, professionals routinely interacting with veterans involved in the criminal-legal system should become familiarized with recent changes in VA eligibility policies. Such familiarization would support the identification of veterans previously considered ineligible for care; provision of education to these veterans regarding their new eligibility; and referral to appropriate VA-based behavioral health care options. Although conceptually simple, executing such an educational campaign may prove logistically difficult. Given their historical exclusion from VA services, veterans with OTH discharge characterizations are unlikely to seek VA-based services in times of need, instead relying on a broad swath of civilian community-based organizations and resources. Usual approaches to advertising VHA health care policy changes (eg, by notifying VA employees and/or departments providing corresponding services or by circulating information to veteran-focused mailing lists and organizations) likely would prove insufficient. Educational campaigns to disseminate information about recent OTH eligibility changes should instead consider partnering with traditionally civilian, communitybased organizations and institutions, such as state bar associations, legal aid networks, case management services, nonveteran treatment court programs (eg, drug courts, or domestic violence courts), or probation/ parole programs. Because national surveys suggest generally low military cultural competence among civilian populations, providing concurrent support in developing foundational veteran cultural competencies (eg, how to phrase questions about military service history, or understanding discharge characterizations) may be necessary to ensure effective identification and engagement of veteran clients.48

Programs that serve veterans with criminal-legal involvement should also consider potential relevance of recent OTH eligibility changes to program operations. VTC program staff and key partners (eg, judges, case managers, district attorneys, or defense attorneys), should revisit policies and procedures surrounding the engagement of veterans with OTH discharges within VTC programs and strategies for connecting these veterans with needed services. VTC programs that have historically excluded veterans with OTH discharges due to associated difficulties in locating and connecting with needed services should consider expanding eligibility policies considering recent shifts in VA behavioral health care eligibility.33,35,36 Within the VHA, VJO specialists can play a critical role in supporting these VTC eligibility and cultural shifts. Some evidence suggests a large proportion of VTC referrals are facilitated by VJO specialists and that many such referrals are identified when veterans involved with the criminal-legal system seek VA support and/or services.33 Given the historical exclusion of veterans with OTH discharges from VA care, strategies used by VJO specialists to identify, connect, and engage veterans with OTH discharges with VTCs and other services may be beneficial.

Even with knowledge of VA eligibility changes and considerations of these changes on local operations, many forensic settings and programs struggle to identify veterans. These difficulties are likely amplified among veterans with OTH discharge characterizations, who may be hesitant to self-disclose their military service history due to fear of stigma and/or views of OTH discharge characterizations as undeserving of the veteran title.12 The VA offers 2 tools to aid in identification of veterans for these settings: the Veterans Re-Entry Search Service (VRSS) and Status Query and Response Exchange System (SQUARES). For VRSS, correctional facilities, courts, and other criminal justice entities upload a simple spreadsheet that contains basic identifying information of inmates or defendants in their system. VRSS returns information about which inmates or defendants have a history of military service and alerts VA Veterans Justice Programs staff so they can conduct outreach. A pilot study conducted by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation found that 2.7% of its inmate population self-identified as veterans, while VRSS identified 7.7% of inmates with a history of military service. This difference represented about 5000 previously unidentified veterans.51 Similarly, community entities that partner with the VA, such as law enforcement or homeless service programs, can be approved to become a SQUARES user and submit identifying information of individuals with whom they interact directly into the SQUARES search engine. SQUARES then directly returns information about the individual’s veteran status and eligibility for VA health care and homeless programs.

Other Eligibility Limitations

VTCs and other professionals looking to refer veterans with OTH discharge characterizations to VA-based behavioral health care should be aware of potential limitations in eligibility and access. Specifically, although veterans with OTH discharges are now broadly eligible for VA-based behavioral health care and homeless programs, they remain ineligible for other forms of health care, including primary care and nonbehavioral specialty care.1 Research has found a strong comorbidity between behavioral and nonbehavioral health concerns, particularly within historically marginalized demographic groups.52-55 Because these historically marginalized groups are often overrepresented among persons with criminal-legal involvement, veterans with OTH discharges, and VTC participants, such comorbidities require consideration by services or programming designed to support veterans with criminal-legal involvement.12,56-58 Connection with VA-based health care will therefore continue to fall short of addressing all health care needs of veterans with OTH discharges and effective case management will require considerable treatment coordination between VA behavioral health care practitioners (HCPs) and community-based HCPs (eg, primary care professionals or nonbehavioral HCPs).

Implications for VA Mental Health Care

Recent eligibility expansions will also have inevitable consequences for VA mental health care systems. For many years, these systems have been overburdened by high caseloads and clinician burnout.59,60 Given the generally elevated rates of mental health and substance use concerns among veterans with OTH discharge characterizations, expansions hold the potential to further burden caseloads with clinically complex, high-risk, high-need clients. Nevertheless, these expansions are also structured in a way that forces existing systems to absorb the responsibilities of providing necessary care to these veterans. To mitigate detrimental effects of eligibility expansions on the broader VA mental health system, clinicians should be explicitly trained in identifying veterans with OTH discharge characterizations and the implications of discharge status on broader health care eligibility. Treatment of veterans with OTH discharges may also benefit from close coordination between mental health professionals and behavioral health care coordinators to ensure appropriate coordination of care between VA- and non–VA-based HCPs.

CONCLUSIONS

Recent changes to VA eligibility policies now allow comprehensive mental and behavioral health care services to be provided to veterans with OTH discharges.1 Compared to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are more likely to be persons of color, sexual or gender minorities, and experiencing mental health-related difficulties. Given the disproportionate mental health burden often faced by veterans with OTH discharges and relative overrepresentation of these veterans in judicial and correctional systems, these changes have considerable implications for programs and services designed to support veterans with criminallegal involvement. Professionals within these systems, particularly VTC programs, are therefore encouraged to familiarize themselves with recent changes in VA eligibility policies and to revisit strategies, policies, and procedures surrounding the engagement and enrollment of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations. Doing so may ensure veterans with OTH discharges are effectively connected to needed behavioral health care services.

- US Department of Veterans, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1601A.02(6): Eligibility Determination. Updated March 6, 2024. Accessed August 8, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8908

- Mental and behavioral health care for certain former members of the Armed Forces. 38 USC §1720I (2018). Accessed August 5, 2024. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:38%20section:1720I%20edition:prelim

- US Department of Veterans, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1601A.02, Eligibility Determination. June 7, 2017.

- US Department of Veterans, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1115(1), Military Sexual Trauma (MST) Program. May 8, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2024. https:// www.va.gov/vhapublications/viewpublication.asp?pub_ID=6402

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Tentative Eligibility Determinations; Presumptive Eligibility for Psychosis and Other Mental Illness. 38 CFR §17.109. May 14, 2013. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/05/14/2013-11410/tentative-eligibility-determinations-presumptive-eligibility-for-psychosis-and-other-mental-illness

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. National strategy for preventing veteran suicide 2018-2028. Published September 2018. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA secretary announces intention to expand mental health care to former service members with other-than-honorable discharges and in crisis. Press Release. March 8, 2017. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=2867

- Smith C. Dramatic increase in mental health services to other-than-honorable discharge veterans. VA News. February 23, 2022. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://news.va.gov/100460/dramatic-increase-in-mental-health-services-to-other-than-honorable-discharge-veterans/

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 1332.14. Enlisted administrative separations. Updated August 1, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/133214p.pdf

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 1332.30. Commissioned officer administrative separations. Updated September 9, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/133230p.pdf

- OUTVETS, Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School, Veterans Legal Services. Turned away: how the VA unlawfully denies healthcare to veterans with bad paper discharges. 2020. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://legalservicescenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Turn-Away-Report.pdf

- McClean H. Discharged and discarded: the collateral consequences of a less-than-honorable military discharge. Columbia Law Rev. 2021;121(7):2203-2268.

- Veterans Benefits, General Provisions, Definitions. 38 USC §101(2) (1958). Accessed August 5, 2024. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title38-section101&num=0&edition=prelim

- Bedford JR. Other than honorable discharges: unfair and unjust life sentences of decreased earning capacity. U Penn J Law Pub Affairs. 2021;6(4):687.

- Karin ML. Other than honorable discrimination. Case Western Reserve Law Rev. 2016;67(1):135-191. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss1/9

- Veteran HOUSE Act of 2020, HR 2398, 116th Cong, (2020). Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/2398

- Scapardine D. Leaving other than honorable soldiers behind: how the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs inadvertently created a health and social crisis. Md Law Rev. 2017;76(4):1133-1165.

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Brancu M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors and other than honorable military discharge: providing healthcare to previously ineligible veterans. Mil Med. 2018;183(9-10):e532-e538. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx128

- Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Characteristics and health needs of veterans with other-than-honorable discharges: expanding eligibility in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2018;183(5-6):e153-e157. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx110

- Christensen DM, Tsilker Y. Racial disparities in military justice: findings of substantial and persistent racial disparities within the United States military justice system. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.protectourdefenders.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Report_20.pdf

- Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, 10 USC §654 (1993) (Repealed 2010). Accessed August 5, 2024. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title10/pdf/USCODE-2010-title10-subtitleA-partII-chap37-sec654.pdf

- Palm Center. The making of a ban: how DTM-19-004 works to push transgender people out of military service. 2019. March 20, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.palmcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/The-Making-of-a-Ban.pdf

- Edwards ER, Greene AL, Epshteyn G, Gromatsky M, Kinney AR, Holliday R. Mental health of incarcerated veterans and civilians: latent class analysis of the 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates. Crim Justice Behav. 2022;49(12):1800- 1821. doi:10.1177/00938548221121142

- Brignone E, Fargo JD, Blais RK, Carter ME, Samore MH, Gundlapalli AV. Non-routine discharge from military service: mental illness, substance use disorders, and suicidality. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):557-565. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.015

- Gamache G, Rosenheck R, Tessler R. Military discharge status of homeless veterans with mental illness. Mil Med. 2000;165(11):803-808. doi:10.1093/milmed/165.11.803

- Gundlapalli AV, Fargo JD, Metraux S, et al. Military Misconduct and Homelessness Among US Veterans Separated From Active Duty, 2001-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(8):832-834. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.8207

- Brooks Holliday S, Pedersen ER. The association between discharge status, mental health, and substance misuse among young adult veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:428-434. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.011

- Williamson RB. DOD Health: Actions Needed to Ensure Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic Brain Injury are Considered in Misconduct Separations. US Government Accountability Office; 2017. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1168610.pdf

- Maruschak LM, Bronson J, Alper M. Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners: survey of prison inmates. US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics. June 2021. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/imhprpspi16st.pdf

- Brooke E, Gau J. Military service and lifetime arrests: examining the effects of the total military experience on arrests in a sample of prison inmates. Crim Justice Policy Rev. 2018;29(1):24-44. doi:10.1177/0887403415619007

- Russell RT. Veterans treatment court: a proactive approach. N Engl J Crim Civ Confin. 2009;35:357-372.

- Cartwright T. To care for him who shall have borne the battle: the recent development of Veterans Treatment Courts in America. Stanford Law Pol Rev. 2011;22:295-316.

- Douds AS, Ahlin EM, Howard D, Stigerwalt S. Varieties of veterans’ courts: a statewide assessment of veterans’ treatment court components. Crim Justice Policy Rev. 2017;28:740-769. doi:10.1177/0887403415620633

- Rowen J. Worthy of justice: a veterans treatment court in practice. Law Policy. 2020;42(1):78-100. doi:10.1111/lapo.12142

- Timko C, Flatley B, Tjemsland A, et al. A longitudinal examination of veterans treatment courts’ characteristics and eligibility criteria. Justice Res Policy. 2016;17(2):123-136.

- Baldwin JM. Executive summary: national survey of veterans treatment courts. SSRN. Preprint posted online June 5, 2013. Accessed August 5, 2024. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2274138

- Renz T. Veterans treatment court: a hand up rather than lock up. Richmond Public Interest Law Rev. 2013;17(3):697-705. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/pilr/vol17/iss3/6

- Knudsen KJ, Wingenfeld S. A specialized treatment court for veterans with trauma exposure: implications for the field. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(2):127-135. doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9845-9

- McCall JD, Tsai J, Gordon AJ. Veterans treatment court research: participant characteristics, outcomes, and gaps in the literature. J Offender Rehabil. 2018;57:384-401. doi:10.1080/10509674.2018.1510864

- Smith JS. The Anchorage, Alaska veterans court and recidivism: July 6, 2004 – December 31, 2010. Alsk Law Rev. 2012;29(1):93-111.

- Hartley RD, Baldwin JM. Waging war on recidivism among justice-involved veterans: an impact evaluation of a large urban veterans treatment court. Crim Justice Policy Rev. 2019;30(1):52-78. doi:10.1177/0887403416650490

- Tsai J, Flatley B, Kasprow WJ, Clark S, Finlay A. Diversion of veterans with criminal justice involvement to treatment courts: participant characteristics and outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(4):375-383. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201600233

- Edwards ER, Sissoko DR, Abrams D, Samost D, La Gamma S, Geraci J. Connecting mental health court participants with services: process, challenges, and recommendations. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2020;26(4):463-475. doi:10.1037/law0000236

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. US Department of Veterans Affairs; November 2023. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- Finlay AK, Clark S, Blue-Howells J, et al. Logic model of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ role in veterans treatment courts. Drug Court Rev. 2019;2:45-62.

- Finlay AK, Smelson D, Sawh L, et al. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs veterans justice outreach program: connecting justice-involved veterans with mental health and substance use disorder treatment. Crim Justice Policy Rev. 2016;27(2):10.1177/0887403414562601. doi:10.1177/0887403414562601

- Finlay AK, Stimmel M, Blue-Howells J, et al. Use of Veterans Health Administration mental health and substance use disorder treatment after exiting prison: the health care for reentry veterans program. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2017;44(2):177-187. doi:10.1007/s10488-015-0708-z

- Meyer EG, Writer BW, Brim W. The Importance of Military Cultural Competence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(3):26. doi:10.1007/s11920-016-0662-9

- National Association of Drug Court Professionals. Adult Drug Court Best Practice Standards Volume I. National Association of Drug Court Professionals; 2013. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://allrise.org/publications/standards/

- STRONG Veterans Act of 2022, HR 6411, 117th Cong (2022). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6411/text

- Pelletier D, Clark S, Davis L. Veterans reentry search service (VRSS) and the SQUARES application. Presented at: National Association of Drug Court Professionals Conference; August 15-18, 2021; National Harbor, Maryland.

- Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Association of Mental Disorders With Subsequent Chronic Physical Conditions: World Mental Health Surveys From 17 Countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):150-158. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688

- Ahmed N, Conway CA. Medical and mental health comorbidities among minority racial/ethnic groups in the United States. J Soc Beh Health Sci. 2020;14(1):153-168. doi:10.5590/JSBHS.2020.14.1.11

- Hanna B, Desai R, Parekh T, Guirguis E, Kumar G, Sachdeva R. Psychiatric disorders in the U.S. transgender population. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;39:1-7.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.09.009

- Watkins DC, Assari S, Johnson-Lawrence V. Race and ethnic group differences in comorbid major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and chronic medical conditions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(3):385- 394. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0085-z

- Baldwin J. Whom do they serve? National examination of veterans treatment court participants and their challenges. Crim Justice Policy Rev. 2017;28(6):515-554. doi:10.1177/0887403415606184

- Beatty LG, Snell TL. Profile of prison inmates, 2016. US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics. December 2021. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppi16.pdf

- Al-Rousan T, Rubenstein L, Sieleni B, Deol H, Wallace RB. Inside the nation’s largest mental health institution: a prevalence study in a state prison system. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):342. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4257-0

- Rosen CS, Kaplan AN, Nelson DB, et al. Implementation context and burnout among Department of Veterans Affairs psychotherapists prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2023;320:517-524. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.141

- Tsai J, Jones N, Klee A, Deegan D. Job burnout among mental health staff at a veterans affairs psychosocial rehabilitation center. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(2):294- 297. doi:10.1007/s10597-019-00487-5

In April 2022, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) revised its behavioral health care eligibility policies to provide comprehensive mental and behavioral health care to former service members who received an Other Than Honorable (OTH) discharge characterization upon separation from military service.1 This policy shift represents a marked expansion in eligibility practices (Table 1 includes amended eligibility criteria).

Since June 2017, eligibility policies allowed veterans with OTH discharges to receive “emergent mental health services” needed to stabilize acute mental health crises related to military service (eg, acute escalations in suicide risk).2,3 Previously, veterans with OTH discharges were largely ineligible for VA-based health care; these individuals were only able to access Veterans Health Administration (VHA) mental and behavioral health care through limited channels of eligibility (eg, for treatment of military sexual trauma or psychosis or other mental illness within 2 years of discharge).4,5 The impetus for expansions in eligibility stemmed from VA efforts to reduce the suicide rate among veterans.6-8 Implications of such expansion extend beyond suicide prevention efforts, with notable promised effects on the care of veterans with criminal-legal involvement. This article highlights potential effects of recent eligibility expansions on veterans with criminal-legal involvement and makes specific recommendations for agencies and organizations serving these veterans.

OTHER THAN HONORABLE DISCHARGE

The US Department of Defense delineates 6 discharge characterizations provided to service members upon separation from military service: honorable, general under honorable conditions, OTH, bad conduct, dishonorable, and uncharacterized. Honorable discharge characterizations are considered to reflect general concordance between service member behavior and military standards; general discharge characterizations reflect some disparity between the service member’s behavior and military standards; OTH, bad conduct, and dishonorable discharge characterizations reflect serious disparities between the service member’s behavior and military standards; and uncharacterized discharge characterizations are given when other discharge characterizations are deemed inappropriate.9,10 OTH discharge characterizations are typically issued under instances of misconduct, fraudulent entry, security reasons, or in lieu of trial by court martial.9,10

Recent research suggests that about 85% of service members receive an honorable discharge characterization upon separation from military service, 8% receive general, 6% receive OTH, and 1% receive bad conduct or dishonorable discharges.11 In 2017, the VA estimated there were > 500,000 prior service members with OTH discharge characterizations, which has grown over time (1.9% during the Korean Conflict, 2.5% during the Vietnam War Era, 3.9% during the Cold War, 4.8% in the Persian Gulf War, and 5.8% in the post-9/11 era).7,11

The OTH discharge characterization is 1 of 3 less than honorable discharges informally referred to as bad papers (ie, OTH, bad conduct, or dishonorable). Former service members receiving these discharge characterizations face significant social stigma and structural discrimination upon military discharge, including significant hurdles to employment and educational pursuits as well as notable social alienation.12 Due to their discharge characterization, some are viewed as less deserving of the veteran title, and until recently, many did not qualify for the complex legal definition of veteran as established by the Congress.11,13 Veterans with OTH discharge characterizations have also historically been excluded from services (eg, VHA care),3 benefits (eg, disability compensation),14 and protections (eg, Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act)15 offered to veterans with honorable or general discharge characterizations. However, eligibility policies have gradually expanded, providing veterans with OTH discharges with access to VHA-based mental and behavioral health services and VA supportive housing assistance.1,3,16

Perhaps due to their historical exclusion from VA services, there is limited research available on the behavioral health and associated needs of veterans with OTH discharges. Some scholars argue that historical exclusions have exacerbated underlying difficulties faced by this population, thereby contributing to stark health and social disparities across discharge types.14,15,17 Studies with large veteran samples, for example, reflect notable demographic and behavioral health differences across discharge types. Compared to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are significantly more likely to be younger, have lower income, use substances, have a history of criminal-legal involvement, and have mental and physical health difficulties.18,19

Substantial evidence also suggests a historical racial bias, with service members of color being disproportionately more likely to receive an OTH discharge.12 Similarly, across all branches of military service, Black service members are significantly more likely to face general or special court martial in military justice proceedings when compared with White service members.20 Service members from gender and sexual minorities are also disproportionately impacted by the OTH designation. Historically, many have been discharged with bad papers due to discriminatory policies, such as Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, which discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation between December 1993 and September 2011, and Directive-type Memorandum-19-004, which banned transgender persons from military service between April 2019 and January 2021.21,22

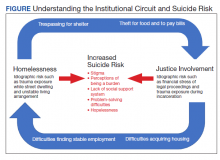

There is also significant mental health bias in the provision of OTH discharges, such that OTH characterizations are disproportionately represented among individuals with mental health disorders.18-20 Veterans discharged from military service due to behavioral misconduct are significantly more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for various behavioral health conditions and to experience homelessness, criminal-legal involvement, and suicidal ideation and behavior compared with routinely-discharged veterans.23-28

Consistent with their comparatively higher rates of criminal-legal involvement relative to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are disproportionately represented in criminal justice settings. While veterans with OTH discharges represent only 6% of discharging service members and 2.5% of community-based veterans, they represent 10% of incarcerated veterans.11,18,23,29 Preliminary research suggests veterans with OTH discharges may be at higher risk for lifetime incarceration, though the association between OTH discharge and frequency of lifetime arrests remains unclear.18,30

VETERANS TREATMENT COURTS

Given the overrepresentation of veterans with OTH discharges in criminal-legal settings, consideration for this subset of the veteran population and its unique needs is commonplace among problem-solving courts that service veterans. First conceptualized in 2004, Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs) are specialized problem-solving courts that divert veterans away from traditional judicial court and penal systems and into community-based supervision and treatment (most commonly behavioral health services).31-34 Although each VTC program is unique in structure, policies, and procedures, most VTCs can be characterized by certain key elements, including voluntary participation, plea requirements, delayed sentencing (often including reduced or dismissed charges), integration of military culture into court proceedings, a rehabilitative vs adversarial approach to decreasing risk of future criminal behavior, mandated treatment and supervision during participation, and use of veteran mentors to provide peer support.32-35 Eligibility requirements vary; however, many restrict participation to veterans with honorable discharge types and charges for nonviolent offenses.32,33,35-37

VTCs connect veterans within the criminal-legal system to needed behavioral health, community, and social services.31-33,37 VTC participants are commonly connected to case management, behavioral health care, therapeutic journaling programs, and vocational rehabilitation.38,39 Accordingly, the most common difficulties faced by veterans participating in these courts include substance use, mental health, family issues, anger management and/or aggressive behavior, and homelessness.36,39 There is limited research on the effectiveness of VTCs. Evidence on their overall effectiveness is largely mixed, though some studies suggest VTC graduates tend to have lower recidivism rates than offenders more broadly or persons who terminate VTC programs prior to completion.40,41 Other studies suggest that VTC participants are more likely to have jail sanctions, new arrests, and new incarcerations relative to nontreatment court participants.42 Notably, experimental designs (considered the gold standard in assessing effectiveness) to date have not been applied to evaluate the effectiveness of VTCs; as such, the effectiveness of these programs remains an area in need of continued empirical investigation.

Like all problem-solving courts, VTCs occasionally struggle to connect participating defendants with appropriate care, particularly when encountering structural barriers (eg, insurance, transportation) and/or complex behavioral health needs (eg, personality disorders).34,43 As suicide rates among veterans experiencing criminal-legal involvement surge (about 150 per 100,000 in 2021, a 10% increase from 2020 to 2021 compared to about 40 per 100,000 and a 1.8% increase among other veterans), efficiency of adequate care coordination is vital.44 Many VTCs rely on VTC-VA partnerships and collaborations to navigate these difficulties and facilitate connection of participating veterans to needed services.32-34,45 For example, within the VHA, Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-Entry Veterans (HCRV) specialists assist and bridge the gap between the criminal-legal system (including, but not limited to VTCs) and VA services by engaging veterans involved in the criminal-legal system and connecting them to needed VA-based services (Table 2). Generally, VJO specialists support veterans involved with the front end of the criminallegal system (eg, arrest, pretrial incarceration, or participation in VTCs), while HCRV specialists tend to support veterans transitioning back into the community after a period of incarceration.46,47 Specific to VTCs, VJO specialists typically serve as liaisons between the courts and VA, coordinating VA services for defendants to fulfill their terms of VTC participation.46

The historical exclusion of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations from VA-based services has restricted many from accessing VTC programs.32 Of 17 VTC programs active in Pennsylvania in 2014, only 5 accepted veterans with OTstayH discharges, and 3 required application to and eligibility for VA benefits.33 Similarly, in national surveys of VTC programs, about 1 in 3 report excluding veterans deemed ineligible for VA services.35,36 When veterans with OTH discharges have accessed VTC programs, they have historically relied on non-VA, community-based programming to fulfill treatment mandates, which may be less suited to addressing the unique needs of veterans.48

Veterans who utilize VTCs receive several benefits, namely peer support and mentorship, acceptance into a veteran-centric space, and connection with specially trained staff capable of supporting the veteran through applications for a range of VA benefits (eg, service connection, housing support).31-33,37 Given the disparate prevalence of OTH discharge characterizations among service members from racial, sexual, and gender minorities and among service members with mental health disorders, exclusion of veterans with OTH discharges from VTCs solely based on the type of discharge likely contributes to structural inequities among these already underserved groups by restricting access to these potential benefits. Such structural inequity stands in direct conflict with VTC best practice standards, which admonish programs to adjust eligibility requirements to facilitate access to treatment court programs for historically marginalized groups.49

ELIGIBILITY EXPANSIONS

Given the overrepresentation of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations within the criminal-legal system and historical barriers of these veterans to access needed mental and behavioral health care, expansions in VA eligibility policies could have immense implications for VTCs. First, these expansions could mitigate common barriers to connecting VTC-participating veterans with OTH discharges with needed behavioral health care by allowing these veterans to access established, VA-based services and programming. Expansion may also allow VTCs to serve as a key intercept point for identifying and engaging veterans with OTH discharges who may be unaware of their eligibility for VA-based behavioral health care.

Access to VA health care services is a major resource for VTC participants and a common requirement.32 Eligibility expansion should ease access barriers veterans with OTH discharges commonly face. By providing a potential source of treatment, expansions may also support OTH eligibility practices within VTCs, particularly practices that require participants to be eligible for VA health care.33,35,36 Some VTCs may continue to determine eligibility on the basis of discharge status and remain inaccessible to veterans with OTH discharge characterizations without program-level policy changes.32,36,37

Communicating changes in eligibility policies relevant to veterans with OTH discharges may be a challenge, because many of these individuals have no established channels of communication with the VA. Because veterans with OTH discharges are at increased risk for legal system involvement, VTCs may serve as a unique point of contact to help facilitate communication.18 For example, upon referral to a VTC, veterans with OTH discharges can be identified, VA health care eligibility can be verified, and veterans can connect to VA staff to facilitate enrollment in VA services and care.

VJO specialists are in a favorable position to serve a critical role in utilizing VTCs as a potential intercept point for engaging veterans with OTH discharge characterizations. As outlined in the STRONG Veterans Act of 2022, VJOs are mandated to “spread awareness and understanding of veteran eligibility for the [VJO] Program, including the eligibility of veterans who were discharged from service in the Armed Forces under conditions other than honorable.”50 The Act further requires VJOs to be annually trained in communicating eligibility changes as they arise. Accordingly, VJOs receive ongoing training in a wide variety of critical outreach topics, including changes in eligibility; while VJOs cannot make eligibility determinations, they are tasked with enrolling all veterans involved in the criminal-legal system with whom they interact into VHA services, whether through typical or special eligibility criteria (M. Stimmel, PhD, National Training Director for Veteran Justice Programming, oral communication, July 14, 2023). VJOs therefore routinely serve in this capacity of facilitating VA enrollment of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations.

Recommendations to Veteran-Servicing Judicial Programs

Considering these potential implications, professionals routinely interacting with veterans involved in the criminal-legal system should become familiarized with recent changes in VA eligibility policies. Such familiarization would support the identification of veterans previously considered ineligible for care; provision of education to these veterans regarding their new eligibility; and referral to appropriate VA-based behavioral health care options. Although conceptually simple, executing such an educational campaign may prove logistically difficult. Given their historical exclusion from VA services, veterans with OTH discharge characterizations are unlikely to seek VA-based services in times of need, instead relying on a broad swath of civilian community-based organizations and resources. Usual approaches to advertising VHA health care policy changes (eg, by notifying VA employees and/or departments providing corresponding services or by circulating information to veteran-focused mailing lists and organizations) likely would prove insufficient. Educational campaigns to disseminate information about recent OTH eligibility changes should instead consider partnering with traditionally civilian, communitybased organizations and institutions, such as state bar associations, legal aid networks, case management services, nonveteran treatment court programs (eg, drug courts, or domestic violence courts), or probation/ parole programs. Because national surveys suggest generally low military cultural competence among civilian populations, providing concurrent support in developing foundational veteran cultural competencies (eg, how to phrase questions about military service history, or understanding discharge characterizations) may be necessary to ensure effective identification and engagement of veteran clients.48

Programs that serve veterans with criminal-legal involvement should also consider potential relevance of recent OTH eligibility changes to program operations. VTC program staff and key partners (eg, judges, case managers, district attorneys, or defense attorneys), should revisit policies and procedures surrounding the engagement of veterans with OTH discharges within VTC programs and strategies for connecting these veterans with needed services. VTC programs that have historically excluded veterans with OTH discharges due to associated difficulties in locating and connecting with needed services should consider expanding eligibility policies considering recent shifts in VA behavioral health care eligibility.33,35,36 Within the VHA, VJO specialists can play a critical role in supporting these VTC eligibility and cultural shifts. Some evidence suggests a large proportion of VTC referrals are facilitated by VJO specialists and that many such referrals are identified when veterans involved with the criminal-legal system seek VA support and/or services.33 Given the historical exclusion of veterans with OTH discharges from VA care, strategies used by VJO specialists to identify, connect, and engage veterans with OTH discharges with VTCs and other services may be beneficial.

Even with knowledge of VA eligibility changes and considerations of these changes on local operations, many forensic settings and programs struggle to identify veterans. These difficulties are likely amplified among veterans with OTH discharge characterizations, who may be hesitant to self-disclose their military service history due to fear of stigma and/or views of OTH discharge characterizations as undeserving of the veteran title.12 The VA offers 2 tools to aid in identification of veterans for these settings: the Veterans Re-Entry Search Service (VRSS) and Status Query and Response Exchange System (SQUARES). For VRSS, correctional facilities, courts, and other criminal justice entities upload a simple spreadsheet that contains basic identifying information of inmates or defendants in their system. VRSS returns information about which inmates or defendants have a history of military service and alerts VA Veterans Justice Programs staff so they can conduct outreach. A pilot study conducted by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation found that 2.7% of its inmate population self-identified as veterans, while VRSS identified 7.7% of inmates with a history of military service. This difference represented about 5000 previously unidentified veterans.51 Similarly, community entities that partner with the VA, such as law enforcement or homeless service programs, can be approved to become a SQUARES user and submit identifying information of individuals with whom they interact directly into the SQUARES search engine. SQUARES then directly returns information about the individual’s veteran status and eligibility for VA health care and homeless programs.

Other Eligibility Limitations

VTCs and other professionals looking to refer veterans with OTH discharge characterizations to VA-based behavioral health care should be aware of potential limitations in eligibility and access. Specifically, although veterans with OTH discharges are now broadly eligible for VA-based behavioral health care and homeless programs, they remain ineligible for other forms of health care, including primary care and nonbehavioral specialty care.1 Research has found a strong comorbidity between behavioral and nonbehavioral health concerns, particularly within historically marginalized demographic groups.52-55 Because these historically marginalized groups are often overrepresented among persons with criminal-legal involvement, veterans with OTH discharges, and VTC participants, such comorbidities require consideration by services or programming designed to support veterans with criminal-legal involvement.12,56-58 Connection with VA-based health care will therefore continue to fall short of addressing all health care needs of veterans with OTH discharges and effective case management will require considerable treatment coordination between VA behavioral health care practitioners (HCPs) and community-based HCPs (eg, primary care professionals or nonbehavioral HCPs).

Implications for VA Mental Health Care

Recent eligibility expansions will also have inevitable consequences for VA mental health care systems. For many years, these systems have been overburdened by high caseloads and clinician burnout.59,60 Given the generally elevated rates of mental health and substance use concerns among veterans with OTH discharge characterizations, expansions hold the potential to further burden caseloads with clinically complex, high-risk, high-need clients. Nevertheless, these expansions are also structured in a way that forces existing systems to absorb the responsibilities of providing necessary care to these veterans. To mitigate detrimental effects of eligibility expansions on the broader VA mental health system, clinicians should be explicitly trained in identifying veterans with OTH discharge characterizations and the implications of discharge status on broader health care eligibility. Treatment of veterans with OTH discharges may also benefit from close coordination between mental health professionals and behavioral health care coordinators to ensure appropriate coordination of care between VA- and non–VA-based HCPs.

CONCLUSIONS

Recent changes to VA eligibility policies now allow comprehensive mental and behavioral health care services to be provided to veterans with OTH discharges.1 Compared to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are more likely to be persons of color, sexual or gender minorities, and experiencing mental health-related difficulties. Given the disproportionate mental health burden often faced by veterans with OTH discharges and relative overrepresentation of these veterans in judicial and correctional systems, these changes have considerable implications for programs and services designed to support veterans with criminallegal involvement. Professionals within these systems, particularly VTC programs, are therefore encouraged to familiarize themselves with recent changes in VA eligibility policies and to revisit strategies, policies, and procedures surrounding the engagement and enrollment of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations. Doing so may ensure veterans with OTH discharges are effectively connected to needed behavioral health care services.

In April 2022, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) revised its behavioral health care eligibility policies to provide comprehensive mental and behavioral health care to former service members who received an Other Than Honorable (OTH) discharge characterization upon separation from military service.1 This policy shift represents a marked expansion in eligibility practices (Table 1 includes amended eligibility criteria).

Since June 2017, eligibility policies allowed veterans with OTH discharges to receive “emergent mental health services” needed to stabilize acute mental health crises related to military service (eg, acute escalations in suicide risk).2,3 Previously, veterans with OTH discharges were largely ineligible for VA-based health care; these individuals were only able to access Veterans Health Administration (VHA) mental and behavioral health care through limited channels of eligibility (eg, for treatment of military sexual trauma or psychosis or other mental illness within 2 years of discharge).4,5 The impetus for expansions in eligibility stemmed from VA efforts to reduce the suicide rate among veterans.6-8 Implications of such expansion extend beyond suicide prevention efforts, with notable promised effects on the care of veterans with criminal-legal involvement. This article highlights potential effects of recent eligibility expansions on veterans with criminal-legal involvement and makes specific recommendations for agencies and organizations serving these veterans.

OTHER THAN HONORABLE DISCHARGE

The US Department of Defense delineates 6 discharge characterizations provided to service members upon separation from military service: honorable, general under honorable conditions, OTH, bad conduct, dishonorable, and uncharacterized. Honorable discharge characterizations are considered to reflect general concordance between service member behavior and military standards; general discharge characterizations reflect some disparity between the service member’s behavior and military standards; OTH, bad conduct, and dishonorable discharge characterizations reflect serious disparities between the service member’s behavior and military standards; and uncharacterized discharge characterizations are given when other discharge characterizations are deemed inappropriate.9,10 OTH discharge characterizations are typically issued under instances of misconduct, fraudulent entry, security reasons, or in lieu of trial by court martial.9,10

Recent research suggests that about 85% of service members receive an honorable discharge characterization upon separation from military service, 8% receive general, 6% receive OTH, and 1% receive bad conduct or dishonorable discharges.11 In 2017, the VA estimated there were > 500,000 prior service members with OTH discharge characterizations, which has grown over time (1.9% during the Korean Conflict, 2.5% during the Vietnam War Era, 3.9% during the Cold War, 4.8% in the Persian Gulf War, and 5.8% in the post-9/11 era).7,11

The OTH discharge characterization is 1 of 3 less than honorable discharges informally referred to as bad papers (ie, OTH, bad conduct, or dishonorable). Former service members receiving these discharge characterizations face significant social stigma and structural discrimination upon military discharge, including significant hurdles to employment and educational pursuits as well as notable social alienation.12 Due to their discharge characterization, some are viewed as less deserving of the veteran title, and until recently, many did not qualify for the complex legal definition of veteran as established by the Congress.11,13 Veterans with OTH discharge characterizations have also historically been excluded from services (eg, VHA care),3 benefits (eg, disability compensation),14 and protections (eg, Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act)15 offered to veterans with honorable or general discharge characterizations. However, eligibility policies have gradually expanded, providing veterans with OTH discharges with access to VHA-based mental and behavioral health services and VA supportive housing assistance.1,3,16

Perhaps due to their historical exclusion from VA services, there is limited research available on the behavioral health and associated needs of veterans with OTH discharges. Some scholars argue that historical exclusions have exacerbated underlying difficulties faced by this population, thereby contributing to stark health and social disparities across discharge types.14,15,17 Studies with large veteran samples, for example, reflect notable demographic and behavioral health differences across discharge types. Compared to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are significantly more likely to be younger, have lower income, use substances, have a history of criminal-legal involvement, and have mental and physical health difficulties.18,19

Substantial evidence also suggests a historical racial bias, with service members of color being disproportionately more likely to receive an OTH discharge.12 Similarly, across all branches of military service, Black service members are significantly more likely to face general or special court martial in military justice proceedings when compared with White service members.20 Service members from gender and sexual minorities are also disproportionately impacted by the OTH designation. Historically, many have been discharged with bad papers due to discriminatory policies, such as Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, which discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation between December 1993 and September 2011, and Directive-type Memorandum-19-004, which banned transgender persons from military service between April 2019 and January 2021.21,22

There is also significant mental health bias in the provision of OTH discharges, such that OTH characterizations are disproportionately represented among individuals with mental health disorders.18-20 Veterans discharged from military service due to behavioral misconduct are significantly more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for various behavioral health conditions and to experience homelessness, criminal-legal involvement, and suicidal ideation and behavior compared with routinely-discharged veterans.23-28

Consistent with their comparatively higher rates of criminal-legal involvement relative to routinely discharged veterans, veterans with OTH discharges are disproportionately represented in criminal justice settings. While veterans with OTH discharges represent only 6% of discharging service members and 2.5% of community-based veterans, they represent 10% of incarcerated veterans.11,18,23,29 Preliminary research suggests veterans with OTH discharges may be at higher risk for lifetime incarceration, though the association between OTH discharge and frequency of lifetime arrests remains unclear.18,30

VETERANS TREATMENT COURTS

Given the overrepresentation of veterans with OTH discharges in criminal-legal settings, consideration for this subset of the veteran population and its unique needs is commonplace among problem-solving courts that service veterans. First conceptualized in 2004, Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs) are specialized problem-solving courts that divert veterans away from traditional judicial court and penal systems and into community-based supervision and treatment (most commonly behavioral health services).31-34 Although each VTC program is unique in structure, policies, and procedures, most VTCs can be characterized by certain key elements, including voluntary participation, plea requirements, delayed sentencing (often including reduced or dismissed charges), integration of military culture into court proceedings, a rehabilitative vs adversarial approach to decreasing risk of future criminal behavior, mandated treatment and supervision during participation, and use of veteran mentors to provide peer support.32-35 Eligibility requirements vary; however, many restrict participation to veterans with honorable discharge types and charges for nonviolent offenses.32,33,35-37

VTCs connect veterans within the criminal-legal system to needed behavioral health, community, and social services.31-33,37 VTC participants are commonly connected to case management, behavioral health care, therapeutic journaling programs, and vocational rehabilitation.38,39 Accordingly, the most common difficulties faced by veterans participating in these courts include substance use, mental health, family issues, anger management and/or aggressive behavior, and homelessness.36,39 There is limited research on the effectiveness of VTCs. Evidence on their overall effectiveness is largely mixed, though some studies suggest VTC graduates tend to have lower recidivism rates than offenders more broadly or persons who terminate VTC programs prior to completion.40,41 Other studies suggest that VTC participants are more likely to have jail sanctions, new arrests, and new incarcerations relative to nontreatment court participants.42 Notably, experimental designs (considered the gold standard in assessing effectiveness) to date have not been applied to evaluate the effectiveness of VTCs; as such, the effectiveness of these programs remains an area in need of continued empirical investigation.

Like all problem-solving courts, VTCs occasionally struggle to connect participating defendants with appropriate care, particularly when encountering structural barriers (eg, insurance, transportation) and/or complex behavioral health needs (eg, personality disorders).34,43 As suicide rates among veterans experiencing criminal-legal involvement surge (about 150 per 100,000 in 2021, a 10% increase from 2020 to 2021 compared to about 40 per 100,000 and a 1.8% increase among other veterans), efficiency of adequate care coordination is vital.44 Many VTCs rely on VTC-VA partnerships and collaborations to navigate these difficulties and facilitate connection of participating veterans to needed services.32-34,45 For example, within the VHA, Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-Entry Veterans (HCRV) specialists assist and bridge the gap between the criminal-legal system (including, but not limited to VTCs) and VA services by engaging veterans involved in the criminal-legal system and connecting them to needed VA-based services (Table 2). Generally, VJO specialists support veterans involved with the front end of the criminallegal system (eg, arrest, pretrial incarceration, or participation in VTCs), while HCRV specialists tend to support veterans transitioning back into the community after a period of incarceration.46,47 Specific to VTCs, VJO specialists typically serve as liaisons between the courts and VA, coordinating VA services for defendants to fulfill their terms of VTC participation.46

The historical exclusion of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations from VA-based services has restricted many from accessing VTC programs.32 Of 17 VTC programs active in Pennsylvania in 2014, only 5 accepted veterans with OTstayH discharges, and 3 required application to and eligibility for VA benefits.33 Similarly, in national surveys of VTC programs, about 1 in 3 report excluding veterans deemed ineligible for VA services.35,36 When veterans with OTH discharges have accessed VTC programs, they have historically relied on non-VA, community-based programming to fulfill treatment mandates, which may be less suited to addressing the unique needs of veterans.48

Veterans who utilize VTCs receive several benefits, namely peer support and mentorship, acceptance into a veteran-centric space, and connection with specially trained staff capable of supporting the veteran through applications for a range of VA benefits (eg, service connection, housing support).31-33,37 Given the disparate prevalence of OTH discharge characterizations among service members from racial, sexual, and gender minorities and among service members with mental health disorders, exclusion of veterans with OTH discharges from VTCs solely based on the type of discharge likely contributes to structural inequities among these already underserved groups by restricting access to these potential benefits. Such structural inequity stands in direct conflict with VTC best practice standards, which admonish programs to adjust eligibility requirements to facilitate access to treatment court programs for historically marginalized groups.49

ELIGIBILITY EXPANSIONS

Given the overrepresentation of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations within the criminal-legal system and historical barriers of these veterans to access needed mental and behavioral health care, expansions in VA eligibility policies could have immense implications for VTCs. First, these expansions could mitigate common barriers to connecting VTC-participating veterans with OTH discharges with needed behavioral health care by allowing these veterans to access established, VA-based services and programming. Expansion may also allow VTCs to serve as a key intercept point for identifying and engaging veterans with OTH discharges who may be unaware of their eligibility for VA-based behavioral health care.

Access to VA health care services is a major resource for VTC participants and a common requirement.32 Eligibility expansion should ease access barriers veterans with OTH discharges commonly face. By providing a potential source of treatment, expansions may also support OTH eligibility practices within VTCs, particularly practices that require participants to be eligible for VA health care.33,35,36 Some VTCs may continue to determine eligibility on the basis of discharge status and remain inaccessible to veterans with OTH discharge characterizations without program-level policy changes.32,36,37

Communicating changes in eligibility policies relevant to veterans with OTH discharges may be a challenge, because many of these individuals have no established channels of communication with the VA. Because veterans with OTH discharges are at increased risk for legal system involvement, VTCs may serve as a unique point of contact to help facilitate communication.18 For example, upon referral to a VTC, veterans with OTH discharges can be identified, VA health care eligibility can be verified, and veterans can connect to VA staff to facilitate enrollment in VA services and care.

VJO specialists are in a favorable position to serve a critical role in utilizing VTCs as a potential intercept point for engaging veterans with OTH discharge characterizations. As outlined in the STRONG Veterans Act of 2022, VJOs are mandated to “spread awareness and understanding of veteran eligibility for the [VJO] Program, including the eligibility of veterans who were discharged from service in the Armed Forces under conditions other than honorable.”50 The Act further requires VJOs to be annually trained in communicating eligibility changes as they arise. Accordingly, VJOs receive ongoing training in a wide variety of critical outreach topics, including changes in eligibility; while VJOs cannot make eligibility determinations, they are tasked with enrolling all veterans involved in the criminal-legal system with whom they interact into VHA services, whether through typical or special eligibility criteria (M. Stimmel, PhD, National Training Director for Veteran Justice Programming, oral communication, July 14, 2023). VJOs therefore routinely serve in this capacity of facilitating VA enrollment of veterans with OTH discharge characterizations.

Recommendations to Veteran-Servicing Judicial Programs

Considering these potential implications, professionals routinely interacting with veterans involved in the criminal-legal system should become familiarized with recent changes in VA eligibility policies. Such familiarization would support the identification of veterans previously considered ineligible for care; provision of education to these veterans regarding their new eligibility; and referral to appropriate VA-based behavioral health care options. Although conceptually simple, executing such an educational campaign may prove logistically difficult. Given their historical exclusion from VA services, veterans with OTH discharge characterizations are unlikely to seek VA-based services in times of need, instead relying on a broad swath of civilian community-based organizations and resources. Usual approaches to advertising VHA health care policy changes (eg, by notifying VA employees and/or departments providing corresponding services or by circulating information to veteran-focused mailing lists and organizations) likely would prove insufficient. Educational campaigns to disseminate information about recent OTH eligibility changes should instead consider partnering with traditionally civilian, communitybased organizations and institutions, such as state bar associations, legal aid networks, case management services, nonveteran treatment court programs (eg, drug courts, or domestic violence courts), or probation/ parole programs. Because national surveys suggest generally low military cultural competence among civilian populations, providing concurrent support in developing foundational veteran cultural competencies (eg, how to phrase questions about military service history, or understanding discharge characterizations) may be necessary to ensure effective identification and engagement of veteran clients.48