User login

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

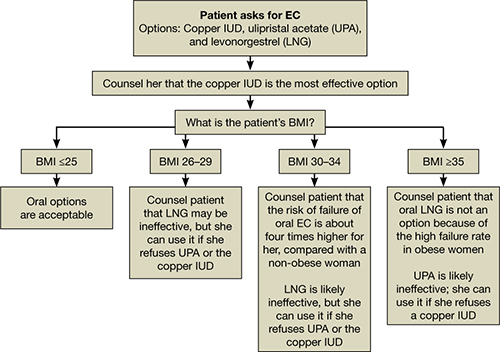

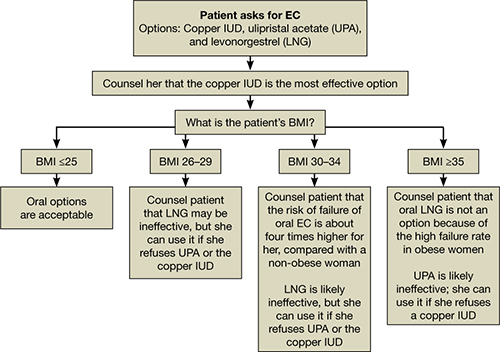

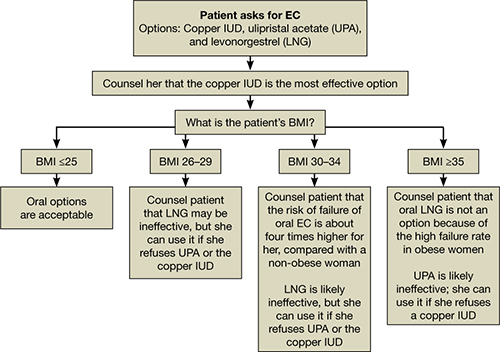

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.