User login

UPDATE ON CONTRACEPTION

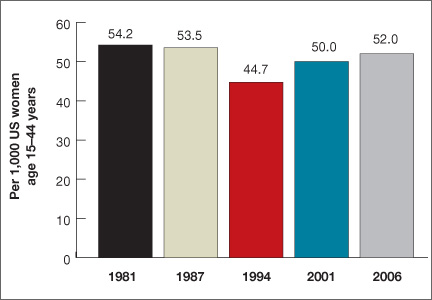

Women spend about 5 years of their reproductive lives trying to get pregnant and the other three decades trying to avoid it.1 Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of these end in abortion.2 In the past 15 years, new contraceptive options have been developed to address this staggering statistic (FIGURE 1). Despite these innovations, the unintended pregnancy rate has increased continually since 1994 (FIGURE 2).23

What are we doing wrong? In this article, we will review how recent innovations are disseminated through the medical community in the context of three specific contraceptive technologies:

-

hysteroscopic sterilization (Essure)

-

ulipristal acetate emergency contraception (Ella)

-

the 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla).

In the process, we assess the available data on the intended and potential impacts of these technologies and describe how ObGyns can best translate these data when considering how to incorporate these new technologies into practice.

| FIGURE 2: Changes in the unintended pregnancy rate, 1981–2006 |

How contraceptive technologies spread in the medical community

Innovations spread through communication channels between individuals of a social network, who are then given time to adopt them. As opinion leaders of a social network become early adopters of a technology, dissemination of the innovation through the social network accelerates.4 This phenomenon is best described by the “diffusion of innovations theory” popularized in 1962 by sociologist Everett Rogers for agricultural applications; he also applied the model to public health.5 The variables he determined to be involved in the acceptance of an innovation are:

-

its relative advantage compared with existing technologies

-

compatibility with current practice

-

low complexity

-

high “trialability” (a potential adopter can easily attempt to use the innovation in his or her practice)

-

high “observability” (the results are easily observed and described to colleagues).

In contrast to new technology itself, medical evidence does not spread rapidly. Data generally spread far more slowly than new technology, typically taking longer than 10 years to influence medical practice.6,7 Opinion leaders can impair the dissemination of data by relying on anecdotal evidence to justify their recommendations.8 Negative findings that challenge these intuitive beliefs can take even longer to disseminate, allowing certain innovations to diffuse through the medical community faster than reports of any associated problems.9

Related article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

How hysteroscopic sterilization gained widespread adoption

Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB, Smith KJ. Reliability of laparoscopic compared with hysteroscopic sterilization at 1 year: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2):273–279.

Since its introduction into the market in 2002, more than 650,000 Essure hysteroscopic sterilization procedures have been performed worldwide.10 This procedure has diffused quickly through the medical community because of the characteristics we mentioned earlier, which ease acceptance in any network:

-

Relative advantage compared with existing technologies. Compared with existing laparoscopic sterilization methods, hysteroscopic sterilization was seen as a less invasive office procedure that could be performed more cost-effectively under local anesthesia, with very high efficacy, if successful.

-

Compatibility with current practice. Because many clinicians were providing in-office hysteroscopy, adding sterilization was a simple step.

-

Low complexity. Hysteroscopic sterilization builds on operative hysteroscopic skills with which gynecologists are familiar.

-

High trialability. The manufacturer’s representatives were willing to bring the instruments to any office for clinicians to try in their practice. The company worked with hysteroscopic equipment companies to create significant discounts for providers who would perform the procedure regularly.

-

High observability. Successful deployment of the devices, and the appearance of the confirmation test, were visualized and described easily as clinicians spoke to other clinicians, helping with dissemination.

Despite these features, however, new data suggest that hysteroscopic sterilization is less effective than laparoscopic sterilization. A successful Essure procedure requires:

-

visualization of both tubal ostia on hysteroscopy

-

successful deployment of the microinserts at the appropriate position

-

hysterosalpingography at least 3 months later (with use of an alternate form of contraception in the interim)

-

demonstrated tubal occlusion by the Essure devices (not by tubal spasm) on hysterosalpingogram.

Although 5-year data collected by the makers of Essure (and posted on their Web site) show a very high rate of efficacy and a failure rate of 0.17%, these data come from women who completed all of the required steps for successful sterilization and study follow-up.

How hysteroscopic sterilization compares with the laparoscopic approach

Gariepy and colleagues created an evidence-based clinical decision analysis to estimate the probability of successful sterilization after a hysteroscopic procedure in the operating room (OR) or office versus laparoscopic sterilization. A decision analysis, which includes the range of data available to assess different outcomes, is the best methodology to provide population-level information about likelihoods, including rare events (eg, pregnancy after sterilization), in the absence of a randomized trial.

A decision analysis assigns women to outcomes based on their intended method of sterilization, mimicking real-life situations created by the multiple steps required for successful completion of the procedure and confirmation of sterilization. When the probabilities of failing these steps are taken into account, 94% and 95% of women choosing hysteroscopic sterilization in the office and OR, respectively, would be successfully sterilized within 1 year, compared with a success rate of 99% in those who opt for laparoscopic sterilization. The estimates of hysteroscopic success include 6% of women who would attempt hysteroscopy but ultimately be sterilized via laparoscopy, and 5% of women who would decline further sterilization attempts after hysteroscopic sterilization fails.

|

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE Hysteroscopic sterilization has its advantages, including a very high efficacy rate among women who meet all the criteria for successful occlusion. Among these criteria is confirmation, by hysterosalpingography, of occlusion 3 months after deployment of the microinserts.10 However, the efficacy of hysteroscopic sterilization is inferior at a population level; therefore, it should not be used indiscriminately. Rather, hysteroscopic sterilization may be a better option for women for whom laparoscopy itself carries a high risk, such as women with complicated diabetes or severe cardiopulmonary disease. While we await similar studies or further trials that evaluate population-based estimates of pregnancy rates, women considering sterilization should be counseled accordingly. |

How limits on access can prevent widespread use of effective contraception

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to emergency contraception. Committee Opinion No. 542. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1250–1253.

Ulipristal acetate as emergency contraception (EC) was introduced to the market in 2010. As was noted in this Update in 2011, ulipristal acetate is more effective than progestin-only emergency contraception and maintains this efficacy for a longer period of time.11 Despite these clear advantages, ulipristal acetate is unlikely to realize its full potential.

Data related to EC as a public health benefit have been largely disappointing. Increased access and availability have not yet reduced the unintended pregnancy rate in the United States. Although use of EC increased from 4.2% in 2002 to 11% in 2008,12 even women with a knowledge of EC do not always use it when needed.13,14

Use of ulipristal acetate, in particular, remains limited because it lacks one important requirement for rapid diffusion—access. Although it is clinically superior to the progestin-only method of EC, is compatible with current practice, and has both high trialability and high observability, access to the drug remains too complex for easy dissemination due to its prescription-only status. Because women can now obtain progestin-only EC over the counter, the use of ulipristal acetate is likely to remain low unless the access barrier to this effective oral EC regimen is reduced.

|

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE When counseling women of reproductive age about contraception, offer them an advance prescription for ulipristal acetate and advise them of its greater efficacy, compared with progestin-only emergency contraception. |

Skyla versus other IUDs: What the data reveal

Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616–622.e1–e3.

The 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla) boasts a smaller frame and a narrower inserter than the two intrauterine devices (IUDs) already on the market (ParaGard and Mirena), a lower amount of levonorgestrel than the other levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena), and 3 years of continuous contraception. Both of the IUDs that predated Skyla are backed by data supporting their efficacy and safety in nulliparous women,15-18 but a number of clinicians and opinion leaders have stated that Skyla’s smaller frame and inserter make it an ideal IUD for the narrower cervical canal and smaller endometrial cavity of nulliparous women,19 including Gemzell-Danielsson and colleagues.

Skyla meets the prerequisites for rapid diffusion; it is highly compatible with current practice and easy to place and use. Of all these characteristics, the relative advantage granted by its size is most likely to promote its diffusion through the medical community.

Ease of placement versus Mirena

Clinical information about Skyla is currently available from two sources. The first is the product package insert, which includes selected data from the product’s Phase 3 study. This study included 1,432 participants, of whom 556 (38.8%) were nulliparous and 540 (37.7%) were treated in the United States.20

The second source is a published, peer-reviewed Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product.21 In the Phase 2 trial, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt. Investigators rated placement for the smaller devices “easy” in 455 of 484 (94.0%) women, compared with 219 of 254 (86.2%) women given Mirena (P <.001). Most of the women given the smaller devices rated their pain with insertion as “mild pain” or “no pain,” compared with those given Mirena (72.3% vs 57.9%; P <.001). Adverse events were similar between users of the different products, except that significantly more women were classified as having an ovarian cyst among Mirena users than among users of the smaller, low-dose devices (22% vs 6%; P <.0001).

Little difference in "clinically relevant" effects

The claim that Skyla has an advantage over Mirena or ParaGard falls short on closer inspection. Although a clinician may prefer easy insertion and a patient with no pain, only very difficult or severely painful placements have clinical relevance.

Investigators rated only 4 of 254 (1.6%) Mirena insertions as “very difficult,” compared with 4 of 484 (0.8%) for the smaller devices (P=.46). Further, women found Mirena insertion to cause severe pain in only 17 of 254 (6.7%) insertions, compared with 21 of 484 (4.3%) placements of the smaller devices (P=.22). The smaller device and inserter, therefore, may have no clinical advantage.

Adverse events were similar

The data on adverse events are similarly misleading. Investigators in the Phase 2 study found that the lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs had an 8.6% rate of ovarian cysts and the Mirena had a 22% rate (P <.0001). However, the Phase 2 study included a pelvic ultrasound examination at every visit, and ovarian cysts were included as an adverse event if the size was 3 cm or greater, regardless of symptoms.

Complaints of abdominal or low abdominal pain were as common among Mirena users as among users of the smaller devices, so this finding likely represents asymptomatic, clinically irrelevant cysts.

Most ovarian cysts found in users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system are asymptomatic.22

Fewer Skyla users developed amenorrhea

Bleeding patterns differed between the products. Users of the smaller, low-dose device reported slightly more spotting and bleeding over the course of a month. In the Phase 2 trial, at the end of 3 years, only 12.7% of Skyla users achieved amenorrhea, compared with 23.6% of Mirena users. The amenorrhea rate for Mirena was very similar to the 20% rate reported in earlier studies,23,24 but the rate for Skyla was even lower (6%) in the larger Phase 3 study.

What about efficacy?

If there are no real advantages to be gained from the size of the device and inserter in terms of pain, and no real improvement in adverse effects or bleeding patterns, what about efficacy?

No direct comparisons are available, but if the devices are evaluated in terms of their first-year Pearl index rating from Phase 3 studies for approval in the United States, then among a cohort of 100,000 users, about 190 Mirena users would become pregnant in the first year, compared with 410 Skyla users.

All IUDs are considered highly effective contraceptives, but small relative differences can have a large impact on a population level if the methods are not used correctly or patients are not counseled appropriately. Although it is more effective than user-dependent contraceptives such as the pill, Skyla is the least effective of the highly effective methods available. If the device has any real benefits in comparison with the other IUDs, they must be better demonstrated with additional data.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

ObGyns have done much to increase the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives such as the IUD (Mirena, ParaGard), the etonogestrel implant (Implanon, Nexplanon), and the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera). We applaud this success and urge ObGyns to continue prescribing these options.

In addition, if we want to have a positive impact on the unintended pregnancy rate, we need to increase awareness of, access to, and use of the most effective contraceptive options in our community of providers and among our patients. We also need to eliminate barriers to use of the most effective methods—eg, discussing ulipristal acetate with our patients and providing advance prescriptions. We also need to be cautious about adopting some innovations, as the data for Skyla and Essure illustrate. They may be terrific options for very specific populations of women, but indiscriminate use may, paradoxically, increase the rate of unintended pregnancy.

Women spend about 5 years of their reproductive lives trying to get pregnant and the other three decades trying to avoid it.1 Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of these end in abortion.2 In the past 15 years, new contraceptive options have been developed to address this staggering statistic (FIGURE 1). Despite these innovations, the unintended pregnancy rate has increased continually since 1994 (FIGURE 2).23

What are we doing wrong? In this article, we will review how recent innovations are disseminated through the medical community in the context of three specific contraceptive technologies:

-

hysteroscopic sterilization (Essure)

-

ulipristal acetate emergency contraception (Ella)

-

the 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla).

In the process, we assess the available data on the intended and potential impacts of these technologies and describe how ObGyns can best translate these data when considering how to incorporate these new technologies into practice.

| FIGURE 2: Changes in the unintended pregnancy rate, 1981–2006 |

How contraceptive technologies spread in the medical community

Innovations spread through communication channels between individuals of a social network, who are then given time to adopt them. As opinion leaders of a social network become early adopters of a technology, dissemination of the innovation through the social network accelerates.4 This phenomenon is best described by the “diffusion of innovations theory” popularized in 1962 by sociologist Everett Rogers for agricultural applications; he also applied the model to public health.5 The variables he determined to be involved in the acceptance of an innovation are:

-

its relative advantage compared with existing technologies

-

compatibility with current practice

-

low complexity

-

high “trialability” (a potential adopter can easily attempt to use the innovation in his or her practice)

-

high “observability” (the results are easily observed and described to colleagues).

In contrast to new technology itself, medical evidence does not spread rapidly. Data generally spread far more slowly than new technology, typically taking longer than 10 years to influence medical practice.6,7 Opinion leaders can impair the dissemination of data by relying on anecdotal evidence to justify their recommendations.8 Negative findings that challenge these intuitive beliefs can take even longer to disseminate, allowing certain innovations to diffuse through the medical community faster than reports of any associated problems.9

Related article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

How hysteroscopic sterilization gained widespread adoption

Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB, Smith KJ. Reliability of laparoscopic compared with hysteroscopic sterilization at 1 year: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2):273–279.

Since its introduction into the market in 2002, more than 650,000 Essure hysteroscopic sterilization procedures have been performed worldwide.10 This procedure has diffused quickly through the medical community because of the characteristics we mentioned earlier, which ease acceptance in any network:

-

Relative advantage compared with existing technologies. Compared with existing laparoscopic sterilization methods, hysteroscopic sterilization was seen as a less invasive office procedure that could be performed more cost-effectively under local anesthesia, with very high efficacy, if successful.

-

Compatibility with current practice. Because many clinicians were providing in-office hysteroscopy, adding sterilization was a simple step.

-

Low complexity. Hysteroscopic sterilization builds on operative hysteroscopic skills with which gynecologists are familiar.

-

High trialability. The manufacturer’s representatives were willing to bring the instruments to any office for clinicians to try in their practice. The company worked with hysteroscopic equipment companies to create significant discounts for providers who would perform the procedure regularly.

-

High observability. Successful deployment of the devices, and the appearance of the confirmation test, were visualized and described easily as clinicians spoke to other clinicians, helping with dissemination.

Despite these features, however, new data suggest that hysteroscopic sterilization is less effective than laparoscopic sterilization. A successful Essure procedure requires:

-

visualization of both tubal ostia on hysteroscopy

-

successful deployment of the microinserts at the appropriate position

-

hysterosalpingography at least 3 months later (with use of an alternate form of contraception in the interim)

-

demonstrated tubal occlusion by the Essure devices (not by tubal spasm) on hysterosalpingogram.

Although 5-year data collected by the makers of Essure (and posted on their Web site) show a very high rate of efficacy and a failure rate of 0.17%, these data come from women who completed all of the required steps for successful sterilization and study follow-up.

How hysteroscopic sterilization compares with the laparoscopic approach

Gariepy and colleagues created an evidence-based clinical decision analysis to estimate the probability of successful sterilization after a hysteroscopic procedure in the operating room (OR) or office versus laparoscopic sterilization. A decision analysis, which includes the range of data available to assess different outcomes, is the best methodology to provide population-level information about likelihoods, including rare events (eg, pregnancy after sterilization), in the absence of a randomized trial.

A decision analysis assigns women to outcomes based on their intended method of sterilization, mimicking real-life situations created by the multiple steps required for successful completion of the procedure and confirmation of sterilization. When the probabilities of failing these steps are taken into account, 94% and 95% of women choosing hysteroscopic sterilization in the office and OR, respectively, would be successfully sterilized within 1 year, compared with a success rate of 99% in those who opt for laparoscopic sterilization. The estimates of hysteroscopic success include 6% of women who would attempt hysteroscopy but ultimately be sterilized via laparoscopy, and 5% of women who would decline further sterilization attempts after hysteroscopic sterilization fails.

|

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE Hysteroscopic sterilization has its advantages, including a very high efficacy rate among women who meet all the criteria for successful occlusion. Among these criteria is confirmation, by hysterosalpingography, of occlusion 3 months after deployment of the microinserts.10 However, the efficacy of hysteroscopic sterilization is inferior at a population level; therefore, it should not be used indiscriminately. Rather, hysteroscopic sterilization may be a better option for women for whom laparoscopy itself carries a high risk, such as women with complicated diabetes or severe cardiopulmonary disease. While we await similar studies or further trials that evaluate population-based estimates of pregnancy rates, women considering sterilization should be counseled accordingly. |

How limits on access can prevent widespread use of effective contraception

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to emergency contraception. Committee Opinion No. 542. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1250–1253.

Ulipristal acetate as emergency contraception (EC) was introduced to the market in 2010. As was noted in this Update in 2011, ulipristal acetate is more effective than progestin-only emergency contraception and maintains this efficacy for a longer period of time.11 Despite these clear advantages, ulipristal acetate is unlikely to realize its full potential.

Data related to EC as a public health benefit have been largely disappointing. Increased access and availability have not yet reduced the unintended pregnancy rate in the United States. Although use of EC increased from 4.2% in 2002 to 11% in 2008,12 even women with a knowledge of EC do not always use it when needed.13,14

Use of ulipristal acetate, in particular, remains limited because it lacks one important requirement for rapid diffusion—access. Although it is clinically superior to the progestin-only method of EC, is compatible with current practice, and has both high trialability and high observability, access to the drug remains too complex for easy dissemination due to its prescription-only status. Because women can now obtain progestin-only EC over the counter, the use of ulipristal acetate is likely to remain low unless the access barrier to this effective oral EC regimen is reduced.

|

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE When counseling women of reproductive age about contraception, offer them an advance prescription for ulipristal acetate and advise them of its greater efficacy, compared with progestin-only emergency contraception. |

Skyla versus other IUDs: What the data reveal

Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616–622.e1–e3.

The 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla) boasts a smaller frame and a narrower inserter than the two intrauterine devices (IUDs) already on the market (ParaGard and Mirena), a lower amount of levonorgestrel than the other levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena), and 3 years of continuous contraception. Both of the IUDs that predated Skyla are backed by data supporting their efficacy and safety in nulliparous women,15-18 but a number of clinicians and opinion leaders have stated that Skyla’s smaller frame and inserter make it an ideal IUD for the narrower cervical canal and smaller endometrial cavity of nulliparous women,19 including Gemzell-Danielsson and colleagues.

Skyla meets the prerequisites for rapid diffusion; it is highly compatible with current practice and easy to place and use. Of all these characteristics, the relative advantage granted by its size is most likely to promote its diffusion through the medical community.

Ease of placement versus Mirena

Clinical information about Skyla is currently available from two sources. The first is the product package insert, which includes selected data from the product’s Phase 3 study. This study included 1,432 participants, of whom 556 (38.8%) were nulliparous and 540 (37.7%) were treated in the United States.20

The second source is a published, peer-reviewed Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product.21 In the Phase 2 trial, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt. Investigators rated placement for the smaller devices “easy” in 455 of 484 (94.0%) women, compared with 219 of 254 (86.2%) women given Mirena (P <.001). Most of the women given the smaller devices rated their pain with insertion as “mild pain” or “no pain,” compared with those given Mirena (72.3% vs 57.9%; P <.001). Adverse events were similar between users of the different products, except that significantly more women were classified as having an ovarian cyst among Mirena users than among users of the smaller, low-dose devices (22% vs 6%; P <.0001).

Little difference in "clinically relevant" effects

The claim that Skyla has an advantage over Mirena or ParaGard falls short on closer inspection. Although a clinician may prefer easy insertion and a patient with no pain, only very difficult or severely painful placements have clinical relevance.

Investigators rated only 4 of 254 (1.6%) Mirena insertions as “very difficult,” compared with 4 of 484 (0.8%) for the smaller devices (P=.46). Further, women found Mirena insertion to cause severe pain in only 17 of 254 (6.7%) insertions, compared with 21 of 484 (4.3%) placements of the smaller devices (P=.22). The smaller device and inserter, therefore, may have no clinical advantage.

Adverse events were similar

The data on adverse events are similarly misleading. Investigators in the Phase 2 study found that the lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs had an 8.6% rate of ovarian cysts and the Mirena had a 22% rate (P <.0001). However, the Phase 2 study included a pelvic ultrasound examination at every visit, and ovarian cysts were included as an adverse event if the size was 3 cm or greater, regardless of symptoms.

Complaints of abdominal or low abdominal pain were as common among Mirena users as among users of the smaller devices, so this finding likely represents asymptomatic, clinically irrelevant cysts.

Most ovarian cysts found in users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system are asymptomatic.22

Fewer Skyla users developed amenorrhea

Bleeding patterns differed between the products. Users of the smaller, low-dose device reported slightly more spotting and bleeding over the course of a month. In the Phase 2 trial, at the end of 3 years, only 12.7% of Skyla users achieved amenorrhea, compared with 23.6% of Mirena users. The amenorrhea rate for Mirena was very similar to the 20% rate reported in earlier studies,23,24 but the rate for Skyla was even lower (6%) in the larger Phase 3 study.

What about efficacy?

If there are no real advantages to be gained from the size of the device and inserter in terms of pain, and no real improvement in adverse effects or bleeding patterns, what about efficacy?

No direct comparisons are available, but if the devices are evaluated in terms of their first-year Pearl index rating from Phase 3 studies for approval in the United States, then among a cohort of 100,000 users, about 190 Mirena users would become pregnant in the first year, compared with 410 Skyla users.

All IUDs are considered highly effective contraceptives, but small relative differences can have a large impact on a population level if the methods are not used correctly or patients are not counseled appropriately. Although it is more effective than user-dependent contraceptives such as the pill, Skyla is the least effective of the highly effective methods available. If the device has any real benefits in comparison with the other IUDs, they must be better demonstrated with additional data.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

ObGyns have done much to increase the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives such as the IUD (Mirena, ParaGard), the etonogestrel implant (Implanon, Nexplanon), and the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera). We applaud this success and urge ObGyns to continue prescribing these options.

In addition, if we want to have a positive impact on the unintended pregnancy rate, we need to increase awareness of, access to, and use of the most effective contraceptive options in our community of providers and among our patients. We also need to eliminate barriers to use of the most effective methods—eg, discussing ulipristal acetate with our patients and providing advance prescriptions. We also need to be cautious about adopting some innovations, as the data for Skyla and Essure illustrate. They may be terrific options for very specific populations of women, but indiscriminate use may, paradoxically, increase the rate of unintended pregnancy.

Women spend about 5 years of their reproductive lives trying to get pregnant and the other three decades trying to avoid it.1 Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of these end in abortion.2 In the past 15 years, new contraceptive options have been developed to address this staggering statistic (FIGURE 1). Despite these innovations, the unintended pregnancy rate has increased continually since 1994 (FIGURE 2).23

What are we doing wrong? In this article, we will review how recent innovations are disseminated through the medical community in the context of three specific contraceptive technologies:

-

hysteroscopic sterilization (Essure)

-

ulipristal acetate emergency contraception (Ella)

-

the 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla).

In the process, we assess the available data on the intended and potential impacts of these technologies and describe how ObGyns can best translate these data when considering how to incorporate these new technologies into practice.

| FIGURE 2: Changes in the unintended pregnancy rate, 1981–2006 |

How contraceptive technologies spread in the medical community

Innovations spread through communication channels between individuals of a social network, who are then given time to adopt them. As opinion leaders of a social network become early adopters of a technology, dissemination of the innovation through the social network accelerates.4 This phenomenon is best described by the “diffusion of innovations theory” popularized in 1962 by sociologist Everett Rogers for agricultural applications; he also applied the model to public health.5 The variables he determined to be involved in the acceptance of an innovation are:

-

its relative advantage compared with existing technologies

-

compatibility with current practice

-

low complexity

-

high “trialability” (a potential adopter can easily attempt to use the innovation in his or her practice)

-

high “observability” (the results are easily observed and described to colleagues).

In contrast to new technology itself, medical evidence does not spread rapidly. Data generally spread far more slowly than new technology, typically taking longer than 10 years to influence medical practice.6,7 Opinion leaders can impair the dissemination of data by relying on anecdotal evidence to justify their recommendations.8 Negative findings that challenge these intuitive beliefs can take even longer to disseminate, allowing certain innovations to diffuse through the medical community faster than reports of any associated problems.9

Related article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

How hysteroscopic sterilization gained widespread adoption

Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB, Smith KJ. Reliability of laparoscopic compared with hysteroscopic sterilization at 1 year: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2):273–279.

Since its introduction into the market in 2002, more than 650,000 Essure hysteroscopic sterilization procedures have been performed worldwide.10 This procedure has diffused quickly through the medical community because of the characteristics we mentioned earlier, which ease acceptance in any network:

-

Relative advantage compared with existing technologies. Compared with existing laparoscopic sterilization methods, hysteroscopic sterilization was seen as a less invasive office procedure that could be performed more cost-effectively under local anesthesia, with very high efficacy, if successful.

-

Compatibility with current practice. Because many clinicians were providing in-office hysteroscopy, adding sterilization was a simple step.

-

Low complexity. Hysteroscopic sterilization builds on operative hysteroscopic skills with which gynecologists are familiar.

-

High trialability. The manufacturer’s representatives were willing to bring the instruments to any office for clinicians to try in their practice. The company worked with hysteroscopic equipment companies to create significant discounts for providers who would perform the procedure regularly.

-

High observability. Successful deployment of the devices, and the appearance of the confirmation test, were visualized and described easily as clinicians spoke to other clinicians, helping with dissemination.

Despite these features, however, new data suggest that hysteroscopic sterilization is less effective than laparoscopic sterilization. A successful Essure procedure requires:

-

visualization of both tubal ostia on hysteroscopy

-

successful deployment of the microinserts at the appropriate position

-

hysterosalpingography at least 3 months later (with use of an alternate form of contraception in the interim)

-

demonstrated tubal occlusion by the Essure devices (not by tubal spasm) on hysterosalpingogram.

Although 5-year data collected by the makers of Essure (and posted on their Web site) show a very high rate of efficacy and a failure rate of 0.17%, these data come from women who completed all of the required steps for successful sterilization and study follow-up.

How hysteroscopic sterilization compares with the laparoscopic approach

Gariepy and colleagues created an evidence-based clinical decision analysis to estimate the probability of successful sterilization after a hysteroscopic procedure in the operating room (OR) or office versus laparoscopic sterilization. A decision analysis, which includes the range of data available to assess different outcomes, is the best methodology to provide population-level information about likelihoods, including rare events (eg, pregnancy after sterilization), in the absence of a randomized trial.

A decision analysis assigns women to outcomes based on their intended method of sterilization, mimicking real-life situations created by the multiple steps required for successful completion of the procedure and confirmation of sterilization. When the probabilities of failing these steps are taken into account, 94% and 95% of women choosing hysteroscopic sterilization in the office and OR, respectively, would be successfully sterilized within 1 year, compared with a success rate of 99% in those who opt for laparoscopic sterilization. The estimates of hysteroscopic success include 6% of women who would attempt hysteroscopy but ultimately be sterilized via laparoscopy, and 5% of women who would decline further sterilization attempts after hysteroscopic sterilization fails.

|

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE Hysteroscopic sterilization has its advantages, including a very high efficacy rate among women who meet all the criteria for successful occlusion. Among these criteria is confirmation, by hysterosalpingography, of occlusion 3 months after deployment of the microinserts.10 However, the efficacy of hysteroscopic sterilization is inferior at a population level; therefore, it should not be used indiscriminately. Rather, hysteroscopic sterilization may be a better option for women for whom laparoscopy itself carries a high risk, such as women with complicated diabetes or severe cardiopulmonary disease. While we await similar studies or further trials that evaluate population-based estimates of pregnancy rates, women considering sterilization should be counseled accordingly. |

How limits on access can prevent widespread use of effective contraception

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to emergency contraception. Committee Opinion No. 542. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1250–1253.

Ulipristal acetate as emergency contraception (EC) was introduced to the market in 2010. As was noted in this Update in 2011, ulipristal acetate is more effective than progestin-only emergency contraception and maintains this efficacy for a longer period of time.11 Despite these clear advantages, ulipristal acetate is unlikely to realize its full potential.

Data related to EC as a public health benefit have been largely disappointing. Increased access and availability have not yet reduced the unintended pregnancy rate in the United States. Although use of EC increased from 4.2% in 2002 to 11% in 2008,12 even women with a knowledge of EC do not always use it when needed.13,14

Use of ulipristal acetate, in particular, remains limited because it lacks one important requirement for rapid diffusion—access. Although it is clinically superior to the progestin-only method of EC, is compatible with current practice, and has both high trialability and high observability, access to the drug remains too complex for easy dissemination due to its prescription-only status. Because women can now obtain progestin-only EC over the counter, the use of ulipristal acetate is likely to remain low unless the access barrier to this effective oral EC regimen is reduced.

|

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE When counseling women of reproductive age about contraception, offer them an advance prescription for ulipristal acetate and advise them of its greater efficacy, compared with progestin-only emergency contraception. |

Skyla versus other IUDs: What the data reveal

Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616–622.e1–e3.

The 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla) boasts a smaller frame and a narrower inserter than the two intrauterine devices (IUDs) already on the market (ParaGard and Mirena), a lower amount of levonorgestrel than the other levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena), and 3 years of continuous contraception. Both of the IUDs that predated Skyla are backed by data supporting their efficacy and safety in nulliparous women,15-18 but a number of clinicians and opinion leaders have stated that Skyla’s smaller frame and inserter make it an ideal IUD for the narrower cervical canal and smaller endometrial cavity of nulliparous women,19 including Gemzell-Danielsson and colleagues.

Skyla meets the prerequisites for rapid diffusion; it is highly compatible with current practice and easy to place and use. Of all these characteristics, the relative advantage granted by its size is most likely to promote its diffusion through the medical community.

Ease of placement versus Mirena

Clinical information about Skyla is currently available from two sources. The first is the product package insert, which includes selected data from the product’s Phase 3 study. This study included 1,432 participants, of whom 556 (38.8%) were nulliparous and 540 (37.7%) were treated in the United States.20

The second source is a published, peer-reviewed Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product.21 In the Phase 2 trial, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt. Investigators rated placement for the smaller devices “easy” in 455 of 484 (94.0%) women, compared with 219 of 254 (86.2%) women given Mirena (P <.001). Most of the women given the smaller devices rated their pain with insertion as “mild pain” or “no pain,” compared with those given Mirena (72.3% vs 57.9%; P <.001). Adverse events were similar between users of the different products, except that significantly more women were classified as having an ovarian cyst among Mirena users than among users of the smaller, low-dose devices (22% vs 6%; P <.0001).

Little difference in "clinically relevant" effects

The claim that Skyla has an advantage over Mirena or ParaGard falls short on closer inspection. Although a clinician may prefer easy insertion and a patient with no pain, only very difficult or severely painful placements have clinical relevance.

Investigators rated only 4 of 254 (1.6%) Mirena insertions as “very difficult,” compared with 4 of 484 (0.8%) for the smaller devices (P=.46). Further, women found Mirena insertion to cause severe pain in only 17 of 254 (6.7%) insertions, compared with 21 of 484 (4.3%) placements of the smaller devices (P=.22). The smaller device and inserter, therefore, may have no clinical advantage.

Adverse events were similar

The data on adverse events are similarly misleading. Investigators in the Phase 2 study found that the lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs had an 8.6% rate of ovarian cysts and the Mirena had a 22% rate (P <.0001). However, the Phase 2 study included a pelvic ultrasound examination at every visit, and ovarian cysts were included as an adverse event if the size was 3 cm or greater, regardless of symptoms.

Complaints of abdominal or low abdominal pain were as common among Mirena users as among users of the smaller devices, so this finding likely represents asymptomatic, clinically irrelevant cysts.

Most ovarian cysts found in users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system are asymptomatic.22

Fewer Skyla users developed amenorrhea

Bleeding patterns differed between the products. Users of the smaller, low-dose device reported slightly more spotting and bleeding over the course of a month. In the Phase 2 trial, at the end of 3 years, only 12.7% of Skyla users achieved amenorrhea, compared with 23.6% of Mirena users. The amenorrhea rate for Mirena was very similar to the 20% rate reported in earlier studies,23,24 but the rate for Skyla was even lower (6%) in the larger Phase 3 study.

What about efficacy?

If there are no real advantages to be gained from the size of the device and inserter in terms of pain, and no real improvement in adverse effects or bleeding patterns, what about efficacy?

No direct comparisons are available, but if the devices are evaluated in terms of their first-year Pearl index rating from Phase 3 studies for approval in the United States, then among a cohort of 100,000 users, about 190 Mirena users would become pregnant in the first year, compared with 410 Skyla users.

All IUDs are considered highly effective contraceptives, but small relative differences can have a large impact on a population level if the methods are not used correctly or patients are not counseled appropriately. Although it is more effective than user-dependent contraceptives such as the pill, Skyla is the least effective of the highly effective methods available. If the device has any real benefits in comparison with the other IUDs, they must be better demonstrated with additional data.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

ObGyns have done much to increase the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives such as the IUD (Mirena, ParaGard), the etonogestrel implant (Implanon, Nexplanon), and the injectable contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera). We applaud this success and urge ObGyns to continue prescribing these options.

In addition, if we want to have a positive impact on the unintended pregnancy rate, we need to increase awareness of, access to, and use of the most effective contraceptive options in our community of providers and among our patients. We also need to eliminate barriers to use of the most effective methods—eg, discussing ulipristal acetate with our patients and providing advance prescriptions. We also need to be cautious about adopting some innovations, as the data for Skyla and Essure illustrate. They may be terrific options for very specific populations of women, but indiscriminate use may, paradoxically, increase the rate of unintended pregnancy.

UPDATE ON CONTRACEPTION

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

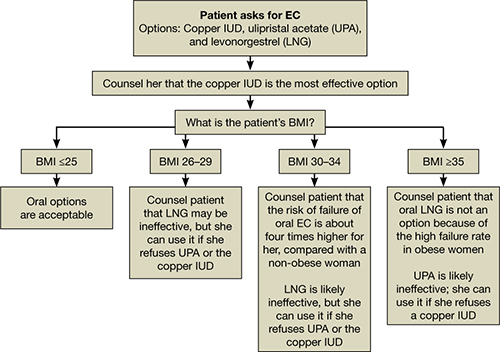

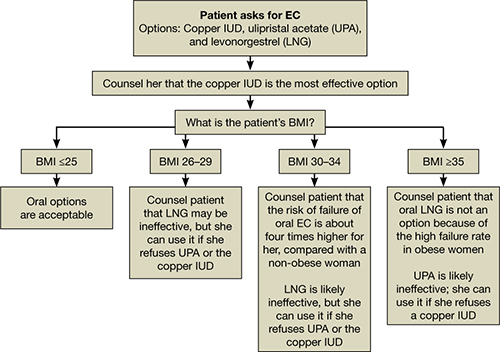

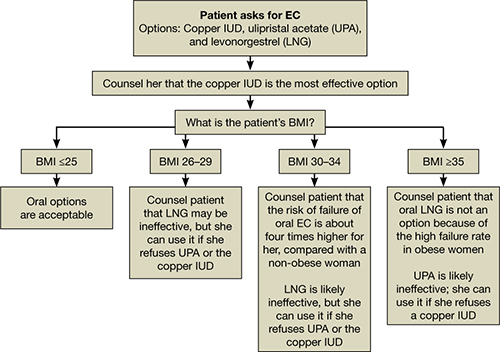

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.