User login

UPDATE: contraception

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

We’ve heard that troubling statistic: Approximately 50% of pregnancies in the United States are unintended. But did you know that one half of those unintended pregnancies occur in women who were using some form of birth control at the time of conception?1 Such pregnancies are due to discontinuation of the method, incorrect use, or method failure.2 The focus of this article is contraceptive counseling, with special attention to:

- which methods of combination hormonal contraception women prefer

- the controversy surrounding the contraceptive patch in regard to thromboembolic disease

- long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the intrauterine device (IUD) and the contraceptive implant, with an emphasis on how LARC is of benefit to both the patient and society.

The ultimate goal of good contraceptive counseling? To help women choose the easiest and most effective method with the fewest side effects.

In head-to-head comparison, women preferred the ring to the patch

Creinin MD, Meyn LA, Borgatta L, et al. Multicenter comparison of the contraceptive ring and patch. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:267–277.

The ethinyl estradiol/etonogestril vaginal ring (NuvaRing) and the ethinyl estradiol/norelgestromin patch (OrthoEvra)—both approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001—are the only nonoral forms of combined hormonal contraception on the market. These methods are said to increase patient compliance and, potentially, efficacy, because they are nondaily forms of contraception.

Until recently, these methods had been compared only with the combination oral contraceptive (OC), but a recent trial compared them directly to each other. At the conclusion of the study, 71% of ring users and 26.5% of patch users planned to continue using the assigned method (P<.001).

This information should aid clinicians in counseling women about which combination hormonal method to choose.

Participants started out using the OC

The multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing the patch and ring included 479 women who were using, and happy with, the combination OC. After rating their satisfaction with the OC, women were randomized to the patch or ring and given 3 months’ worth of product. Follow-up involved only two telephone calls and one visit at the end of the third cycle, because this degree of monitoring was thought to mimic clinical practice.

The percentages of women who completed three cycles of their assigned product were 94.6% and 88.2% in the ring and patch groups, respectively (P=.03). The most common reasons for early discontinuation in the ring group were discomfort and adverse effects. In the patch group, the most common reasons were adverse effects, skin irritation, and adherence problems.

Even after adjusting for age, education, and whether an OC was actively being used at the time the study began, patch users were twice as likely to discontinue the patch at the end of three cycles and seven times more likely to state that they did not want to continue the patch.

Adverse effects were greater than with the pill

Women switching from pill to patch were significantly more likely to report breast pain, nausea, skin rash, longer menstrual bleeding, and menstrual pain than women who switched from the pill to the ring (P<.001).

Women who switched from the pill to the ring were more likely to experience vaginal discharge (P=.003) and a larger amount of vaginal discharge than patch users (P<.001).

These findings are similar to those of previous studies that compared the patch with the pill, noting that breast discomfort, application-site reaction, and dysmenorrhea were more common in patch than pill users.3 Earlier studies also found the ring to be associated with complaints of vaginal discharge.4,5

Findings may not be generalizable

The most important finding from this direct comparison is the difference in patient satisfaction between groups. Visual analog scales showed that women using the ring were happier with the ring than with the pill, whereas women using the patch were happier with the pill than with the patch (P<.001). Questionnaires revealed that women were more satisfied with the ring than they were with the patch, and were more likely to recommend the ring than the patch to a friend (P<.001).

Based on continuation rates, patient satisfaction, and adverse-effect profiles, women in this study clearly preferred the ring to the pill, and the pill to the patch. When using this information to counsel patients, however, it is important to recall that this population was specific. The women had been using an OC, with which they were happy. This study cannot necessarily be generalized to women who are just initiating combination hormonal contraception, but it can be helpful in counseling a patient who may want to switch from an OC to a method that involves nondaily dosing.

Does the contraceptive patch raise the risk of thromboembolism?

Jick SS, Kaye JA, Russman S, Jick H. Risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using a contraceptive patch and oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:223–228.

Jick S, Kaye JA, Li L, Jick H. Further results on the risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in users of the contraceptive transdermal patch compared to users of oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2007;76:4–7.

Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, Walker AM. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):339–346.

Both the media and regulatory agencies have raised concerns about whether the contraceptive patch heightens the risk of thromboembolism and is less effective in women above a certain body weight.

The controversy surrounding thromboembolic disease stems from a pharmacokinetics study by van den Heuvel and colleagues that compared serum ethinyl estradiol levels in users of the patch, vaginal ring, and a combination OC containing 30 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 150 μg of levonorgestrel.6 Women randomized to the patch had serum ethinyl estradiol levels 1.6 times higher than women randomized to an OC, and 3.4 times higher than women randomized to the ring.

These findings led the FDA to update package labeling of the patch to warn health-care providers and patients that the patch exposes women to 60% more estrogen and may increase the risk of thromboembolic events. Oddly, the FDA did not require any labeling change to combination OCs to indicate that they contain up to twice as much estrogen as the contraceptive ring.

A set of studies finds no elevated risk

Although the study by van den Heuvel and associates raised the possibility of increased blood clots in patch users, no association between the two had been corroborated at the time it was published.6 Since then, three epidemiological studies have explored the potential link between thromboembolic events and use of the patch.

In the first of these studies, Jick and colleagues used the PharMetrics database to extract data on users of the patch and norg-estimate-containing OCs. This database contains drug prescription information, patient demographic data, and ICD-9 billing codes submitted by managed care health plans. A nested case-control study design was used to compare patch and pill users and control for confounding variables.

The base population was women 15 to 44 years old who were new users of the patch or a norgestimate-containing OC. A thromboembolic event was diagnosed if the patient’s record included a diagnosis code for pulmonary embolus, deep vein thrombosis, or an emergency room visit or diagnostic testing indicating venous thromboembolism (VTE). These diagnosis codes, combined with the prescription of long-term anticoagulation therapy, strengthened the identification of cases. As many as four controls were selected for each case.

The 215,769 women included in this study contributed 147,323 woman-years of exposure to the drugs. There were 31 and 37 cases of VTE identified in the patch and pill groups, respectively, with an incidence of 52.8 for every 100,000 woman-years in the patch group and 41.8 for every 100,000 woman-years in the pill group and an unadjusted, matched odds ratio of VTE in patch versus pill users of 0.9. When the data were adjusted for duration of drug exposure, the odds ratio did not change.

A follow-up study by Jick and associates, published in 2007, had the same study design and included 17 additional months of data. Another 56 cases of VTE were diagnosed. The odds ratio for patch users, compared with pill users, was 1.1. When data from the two studies were combined, 73 and 51 total cases of VTE had occurred in the pill and patch groups, respectively. The overall odds ratio was 1.0.

A third study finds significantly heightened risk

Cole and associates studied insurance claims data from UnitedHealthcare, a database containing medical and prescription claim information as well as patient demographics. Because researchers used pharmacy dispensing records, they were able to include women 15 to 44 years old who had received at least one prescription for the contraceptive patch or a norgestimate-containing OC with 35 μg of ethinyl estradiol.

Unlike the studies by Jick and colleagues, the study by Cole and associates considered all women eligible, even if they had used OCs in the past. Cases of VTE, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were abstracted from this group, identified from insurance claim information, and confirmed by chart review. Review of medical records is an important strength of this study; no such review was done in the studies by Jick and colleagues. Four controls were matched to each case, by age and duration of contraceptive use.

(This study was commissioned in conjunction with both the FDA and Johnson & Johnson, makers of the contraceptive patch, but researchers had full control over the data and results and were not required to consult with Johnson & Johnson when reporting findings.)

There were 49,048 woman-years of exposure to the patch and 202,344 woman-years of exposure to the pill, with an incidence of VTE of 40.8 and 18.3 for every 100,000 woman-years in patch and pill users, respectively. The incidence of AMI was 6.1 and 3.5 for every 100,000 woman-years in patch and pill users, respectively. No ischemic strokes were noted in patch users.

The adjusted incidence ratio for VTE in patch users compared with pill users was 2.2, and for AMI it was 1.8. Following publication of this study, the FDA issued a statement in January of this year that women using the patch face an increased risk of VTE, compared with women using the pill. Package labeling was changed to reflect this heightened risk.

Reasons for different findings

The studies by Jick and colleagues and Cole and associates present very different findings. The studies by Jick and colleagues give the impression that there is no increased risk of VTE in patch users compared with pill users, but the studies have significant flaws. First, Jick and colleagues do not confirm the diagnosis of VTE in the medical record. This is particularly problematic because the reported number of pulmonary emboli (PE) is very high, compared with the number of deep vein thromboses. The 2006 study found 42 cases of PE and only 26 cases of deep vein thrombosis. Because the latter is more common than PE, this could indicate that deep vein thrombosis was underdiagnosed.

Another shortcoming is that Jick and colleagues included only nonfatal thromboembolic events, which may mean that they missed many cases of fatal VTE because they were not looking for this information. The inclusion of new initiators only also may have skewed the data. This would mean that former users of an OC may have been included in the patch group but were ineligible for inclusion in the pill group. This may bias the data toward experienced hormonal contraceptive users in the patch group, thereby falsely lowering the VTE rate.

The study by Cole and associates also has limitations. It included long-term users of hormonal contraceptives in both the patch and the OC groups, which may bias the data toward lower rates of VTE, AMI, and stroke for the same reasons cited above. One would assume that this bias was corrected, because prior use was allowed in both groups, making the bias equally distributed, but there is no way to confirm this with any degree of certainty.

All three studies have some flaws in common

All three studies used prescription information to determine exposure, but there is no guarantee that the women who filled the prescriptions actually used the agents. Patients given drug samples by their clinicians were overlooked because these samples are not tracked through pharmacy data.

Because the data were collected from insurance claims information of privately insured patients, it is impossible to generalize these findings to the general population. We cannot use the findings to determine whether the same results would be seen in uninsured women or women insured through nonprivate programs such as Medicaid or the Veterans Administration.

So what’s the bottom line?

Health-care providers should be cautious about citing these studies as “evidence” when advising patients about the risk of VTE while using the patch. The twofold increased risk of VTE observed in patch users and the almost twofold increased risk of AMI observed by Cole and associates cannot be completely ignored, however, particularly because this study was better designed than those by Jick and colleagues.

It is more important to remember that the incidence of VTE in patch users is extremely low. If a patient has been using the patch, is happy with the method, and has had no adverse effects, there is no reason, based on these findings, to discontinue it. When counseling new initiators, the best that can be done is to explain the potential risks and side effects associated with the method and allow the patient to make an informed choice using the information that is available.

If the increased risk of VTE is accurate, it would still be equal to or lower than the risk during pregnancy. A recent review found the overall incidence of VTE in pregnancy or the postpartum period to be 200 for every 100,000 woman-years.7

In a pooled analysis of the two studies of the contraceptive patch by Jick and colleagues and the one study by Cole and associates, the overall and method failure rates through 13 cycles were 0.8% and 0.6%, respectively, representing 15 pregnancies.1

Subject weights were divided into deciles to determine the number of pregnancies per decile. Interestingly, that number does not appear to be evenly distributed. In deciles 1 through 9, which represent women who weigh up to 80 kg, the number of pregnancies was eight, whereas seven pregnancies occurred in the 10th decile, which represents women weighing more than 80 kg. Because the number of pregnancies in decile 10 is essentially equivalent to all of the other deciles combined, women who weigh more than 80 kg (176 lb) appear to be at increased risk of pregnancy. Five of the seven pregnancies in decile 10 occurred in women weighing more than 90 kg (198 lb).

No studies have directly explored the reasons for this relationship or looked at body mass index or body surface area in relation to efficacy of the patch. Further research is clearly needed.

How to counsel overweight women

It is imperative that patients who weigh more than 198 lb be informed that the pregnancy rate is higher than the rate quoted for the patch. It may even be reasonable to counsel women in that 10thdecile—who weigh more than 176 lb—about alternative forms of hormonal contraception that would be more effective for them than the patch.

Reference

1. Ziemen M, Guillebaud J, Weisberg E, Shangold GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW. Contraceptive efficacy and cycle control with the Ortho Evra/Evra transdermal system: the analysis of pooled data. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 Suppl 2):S13-S18.

Why don’t American women choose long-acting reversible contraception?

Do American women not want to use long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), or are we, as providers, failing to properly educate them about its benefits?

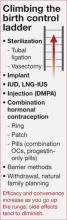

The ParaGard copper IUD, the Mirena levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNGIUS), and the Implanon etonorgestrel contraceptive implant are all highly effective, convenient, long-duration, and reversible (FIGURE). Despite substantial evidence indicating that these methods are well tolerated and highly effective, only about 2% of American women are choosing them to prevent pregnancy.1 This rate lags far behind other countries in IUD utilization. In contrast, more than 50% of contraceptive users in China and Egypt are using intrauterine contraception.8

FIGURE

Copper IUD is effective for 12 years or longer

The copper IUD is FDA-approved for 10 years of use, although studies continue to support its continued efficacy for 12 years or longer.9 The 1-year perfect-use failure rate is 0.6%, and the typical use failure rate is 0.5% to 0.8%.10 The total failure rate over 12 years is 2.2%.9

Benefits. The copper IUD does not increase the risk of intrauterine infection and is safe to place in nulliparous patients.11 It is an excellent choice for women who clearly prefer to have monthly menses and for women who have personal or medical contraindications to hormonal birth control. Women using this method of birth control can expect excellent efficacy, rapid reversibility, and minimal side effects.

Adverse effects. The most common adverse events in copper IUD users are heavier menses and dysmenorrhea. Approximately 4.5% of women discontinue the copper IUD in the first year of use because of these particular side effects.12

LNG-IUS: Highly effective, with important noncontraceptive benefits

This method of birth control is comparable to the copper IUD in terms of efficacy and tolerability. It is FDA-approved for 5 years of use, with a cumulative 5-year failure rate of 0.7 for every 100 women.13 One small study demonstrated that this method is potentially effective up to 7 years, with a 1.1% pregnancy rate.11 With perfect use, the first-year pregnancy rate is 0.1% to 0.2%.14

Benefits. The progestin component provides noncontraceptive benefits, including a reduction in menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea,15 treatment of endometrial hyperplasia16 and endometrial cancer,17 endometrial protection in women using tamoxifen,18 treatment of endometriosis,19 and protection from pelvic inflammatory disease.20

Adverse effects. The primary disadvantage of this device is a change in bleeding pattern in some women, who may experience irregular spotting, primarily in the first 3 to 6 months.21 About 20% of users will become amenorrheic by 12 months of use, a feature that is highly desirable for many, but troubling to some.

Implant is essentially 100% effective

The newest LARC device is the etonorgestrel implant, which was approved by the FDA in July 2006. The single-rod implant is typically placed in the subcuticular tissue of the non-dominant arm, although placement in the dominant arm is fine if the patient prefers.

Benefits. In a 3-year study involving 635 subjects, no pregnancies were reported.22 The reported Pearl index of 0.38 pregnancies for every 100,000 woman-years of use relates to pregnancies that occurred shortly after discontinuation rather than during actual use. These studies included only women below 130% of their ideal body weight who were not using liver enzyme-inducing medications. The pregnancy rate in women who use such medications, or weigh above 130% of their ideal body weight, is unknown. Postmarketing surveillance has reported some pregnancies, as would be expected. The device is easily inserted and easily removed as long as 3 years later.

Adverse effects. The primary adverse effect of this implant is bleeding disturbances; discontinuation was usually due to this side effect.22 The cumulative discontinuation rate was 10% at 6 months, 20% at 12 months, 31% at 2 years, and 32.2% at 3 years.22

Training required. FDA approval included a stipulation that practitioners complete company-sponsored training (www.implanonusa.com) to insert and remove the device.

Overall benefits include minimal side effects, low cost

All LARC methods provide excellent protection against pregnancy (equal to or better than sterilization), have minimal side effects, and are rapidly reversible. They are also appropriate for women in whom combination hormonal contraception is contraindicated, such as smokers older than 35 years and women who have had VTE.

A final and important advantage: These methods are more cost-effective than other contraceptive methods, including combination OCs. They may require a higher initial investment, but the LNG-IUS and copper IUD are the least costly methods of contraception over 5 years of use.23

As providers continue to educate themselves and help women gain a better understanding of which methods are truly highly effective, they will likely begin to recommend LARC more often. Use of these devices has the potential to significantly decrease the high rate of unintended pregnancy.

Authors’ note: The figure at right depicts how the efficacy and convenience of contraceptive options rise (and side effects fall) along a continuum. LARC methods are “high up the ladder”—an observation that serves as food for thought as we counsel patients about what methods of birth control are best for them.

1. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:24-29, 46.

2. Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Long S. Unintended pregnancies and use, misuse and discontinuation of oral contraceptives. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:355-360.

3. Sibai BM, Odlind V, Meador ML, Shangold GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW. A comparative and pooled analysis of the safety and tolerability of the contraceptive patch (Ortho Evra/Evra). Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 Suppl 2):S19-S26.

4. Arhendt HJ, Nisand I, Bastianelli C, et al. Efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of the combined contraceptive ring, NuvaRing, compared with an oral contraceptive containing 30 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone. Contraception. 2006;74:451-457.

5. Oddson K, Leifels-Fischer B, de Melo NR, et al. Efficacy and safety of a contraceptive vaginal ring (NuvaRing) compared with a combined oral contraceptive:a 1-year randomized trial. Contraception. 2005;71:176-182.

6. van den Heuvel MW, van Bragt AJ, Alnabawy AK, Kaptein MC. Comparison of ethinylestradiol pharmacokinetics in three hormonal contraceptive formulations: The vaginal ring, the transdermal patch and an oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2005;72:168-174.

7. Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum:a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697-706.

8. d’Arcangues C. Worldwide use of intrauterine devices for contraception. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl):S2-S7.

9. Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56:341-352.

10. Sivin I, Schmidt F. Effectiveness of IUDs: a review. Contraception. 1987;36:55-84.

11. Rivera R, Chen-Mok M, McMullen S. Analysis of client characteristics that may affect early discontinuation of the TCu-380A IUD. Contraception. 1999;60:155-160.

12. Hubacher D, Lara-Ricalde R, Taylor DJ, Guerra Infante F, Guzmán-Rodríguez R. Use of copper intrauterine devices and the risk of tubal infertility among nulligravid women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:561-567.

13. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In:Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 18th ed. New York: Ardent Media, Inc.;2004:495-530.

14. Sivin I, Stern J. Healthduring prolonged use of levonorgestrel 20 micrograms/d and the copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devices: a multicenter study. International Committee for Contraception Research (ICCR). Fertil Steril. 1994;61:70-77.

15. Kadir RA, Chi C. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system: bleeding disorders and anticoagulant therapy. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl):S123-S129.

16. Wildemeersch D, Dhont M. Treatment of non-atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1297-1298.

17. Dhar KK, NeedhiRajan T, Koslowski M, Woolas RP. Is levonorgestrel intrauterine system effective for treatment of early endometrial cancer? Report of four cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:924-927.

18. Gardner FJ, Konje JC, Abrams KR, et al. Endometrial protection from tamoxifen-stimulated changes by a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system:a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:1711-1717.

19. Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy, side-effects and continuation rates of women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intra-uterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel):a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:789-793.

20. Toivonen J, Luukkainen T, Allonen H. Protective effect of intrauterine release of levonorgestrel on pelvic infection: three years’comparative experience of levonorgestrel-and copper-releasing intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:261-264.

21. Backman T, Huhtala S, Blom T, Luoto R, Rauramo I, Koskenvuo M. Length of use and symptoms associated with premature removal of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system:a nationwide study of 17,360 users. BJOG. 2000;107:335-339.

22. Croxatto HB. Clinical profile of Implanon:a single-rod etonorgestrel contraceptive implant. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2000;5(Suppl 2):21-28.

23. Chiou CF, Trussell J, Reyes E, et al. Economic analysis of contraceptives for women. Contraception. 2003;68:3-10.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

We’ve heard that troubling statistic: Approximately 50% of pregnancies in the United States are unintended. But did you know that one half of those unintended pregnancies occur in women who were using some form of birth control at the time of conception?1 Such pregnancies are due to discontinuation of the method, incorrect use, or method failure.2 The focus of this article is contraceptive counseling, with special attention to:

- which methods of combination hormonal contraception women prefer

- the controversy surrounding the contraceptive patch in regard to thromboembolic disease

- long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the intrauterine device (IUD) and the contraceptive implant, with an emphasis on how LARC is of benefit to both the patient and society.

The ultimate goal of good contraceptive counseling? To help women choose the easiest and most effective method with the fewest side effects.

In head-to-head comparison, women preferred the ring to the patch

Creinin MD, Meyn LA, Borgatta L, et al. Multicenter comparison of the contraceptive ring and patch. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:267–277.

The ethinyl estradiol/etonogestril vaginal ring (NuvaRing) and the ethinyl estradiol/norelgestromin patch (OrthoEvra)—both approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001—are the only nonoral forms of combined hormonal contraception on the market. These methods are said to increase patient compliance and, potentially, efficacy, because they are nondaily forms of contraception.

Until recently, these methods had been compared only with the combination oral contraceptive (OC), but a recent trial compared them directly to each other. At the conclusion of the study, 71% of ring users and 26.5% of patch users planned to continue using the assigned method (P<.001).

This information should aid clinicians in counseling women about which combination hormonal method to choose.

Participants started out using the OC

The multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing the patch and ring included 479 women who were using, and happy with, the combination OC. After rating their satisfaction with the OC, women were randomized to the patch or ring and given 3 months’ worth of product. Follow-up involved only two telephone calls and one visit at the end of the third cycle, because this degree of monitoring was thought to mimic clinical practice.

The percentages of women who completed three cycles of their assigned product were 94.6% and 88.2% in the ring and patch groups, respectively (P=.03). The most common reasons for early discontinuation in the ring group were discomfort and adverse effects. In the patch group, the most common reasons were adverse effects, skin irritation, and adherence problems.

Even after adjusting for age, education, and whether an OC was actively being used at the time the study began, patch users were twice as likely to discontinue the patch at the end of three cycles and seven times more likely to state that they did not want to continue the patch.

Adverse effects were greater than with the pill

Women switching from pill to patch were significantly more likely to report breast pain, nausea, skin rash, longer menstrual bleeding, and menstrual pain than women who switched from the pill to the ring (P<.001).

Women who switched from the pill to the ring were more likely to experience vaginal discharge (P=.003) and a larger amount of vaginal discharge than patch users (P<.001).

These findings are similar to those of previous studies that compared the patch with the pill, noting that breast discomfort, application-site reaction, and dysmenorrhea were more common in patch than pill users.3 Earlier studies also found the ring to be associated with complaints of vaginal discharge.4,5

Findings may not be generalizable

The most important finding from this direct comparison is the difference in patient satisfaction between groups. Visual analog scales showed that women using the ring were happier with the ring than with the pill, whereas women using the patch were happier with the pill than with the patch (P<.001). Questionnaires revealed that women were more satisfied with the ring than they were with the patch, and were more likely to recommend the ring than the patch to a friend (P<.001).

Based on continuation rates, patient satisfaction, and adverse-effect profiles, women in this study clearly preferred the ring to the pill, and the pill to the patch. When using this information to counsel patients, however, it is important to recall that this population was specific. The women had been using an OC, with which they were happy. This study cannot necessarily be generalized to women who are just initiating combination hormonal contraception, but it can be helpful in counseling a patient who may want to switch from an OC to a method that involves nondaily dosing.

Does the contraceptive patch raise the risk of thromboembolism?

Jick SS, Kaye JA, Russman S, Jick H. Risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using a contraceptive patch and oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:223–228.

Jick S, Kaye JA, Li L, Jick H. Further results on the risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in users of the contraceptive transdermal patch compared to users of oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2007;76:4–7.

Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, Walker AM. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):339–346.

Both the media and regulatory agencies have raised concerns about whether the contraceptive patch heightens the risk of thromboembolism and is less effective in women above a certain body weight.

The controversy surrounding thromboembolic disease stems from a pharmacokinetics study by van den Heuvel and colleagues that compared serum ethinyl estradiol levels in users of the patch, vaginal ring, and a combination OC containing 30 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 150 μg of levonorgestrel.6 Women randomized to the patch had serum ethinyl estradiol levels 1.6 times higher than women randomized to an OC, and 3.4 times higher than women randomized to the ring.

These findings led the FDA to update package labeling of the patch to warn health-care providers and patients that the patch exposes women to 60% more estrogen and may increase the risk of thromboembolic events. Oddly, the FDA did not require any labeling change to combination OCs to indicate that they contain up to twice as much estrogen as the contraceptive ring.

A set of studies finds no elevated risk

Although the study by van den Heuvel and associates raised the possibility of increased blood clots in patch users, no association between the two had been corroborated at the time it was published.6 Since then, three epidemiological studies have explored the potential link between thromboembolic events and use of the patch.

In the first of these studies, Jick and colleagues used the PharMetrics database to extract data on users of the patch and norg-estimate-containing OCs. This database contains drug prescription information, patient demographic data, and ICD-9 billing codes submitted by managed care health plans. A nested case-control study design was used to compare patch and pill users and control for confounding variables.

The base population was women 15 to 44 years old who were new users of the patch or a norgestimate-containing OC. A thromboembolic event was diagnosed if the patient’s record included a diagnosis code for pulmonary embolus, deep vein thrombosis, or an emergency room visit or diagnostic testing indicating venous thromboembolism (VTE). These diagnosis codes, combined with the prescription of long-term anticoagulation therapy, strengthened the identification of cases. As many as four controls were selected for each case.

The 215,769 women included in this study contributed 147,323 woman-years of exposure to the drugs. There were 31 and 37 cases of VTE identified in the patch and pill groups, respectively, with an incidence of 52.8 for every 100,000 woman-years in the patch group and 41.8 for every 100,000 woman-years in the pill group and an unadjusted, matched odds ratio of VTE in patch versus pill users of 0.9. When the data were adjusted for duration of drug exposure, the odds ratio did not change.

A follow-up study by Jick and associates, published in 2007, had the same study design and included 17 additional months of data. Another 56 cases of VTE were diagnosed. The odds ratio for patch users, compared with pill users, was 1.1. When data from the two studies were combined, 73 and 51 total cases of VTE had occurred in the pill and patch groups, respectively. The overall odds ratio was 1.0.

A third study finds significantly heightened risk

Cole and associates studied insurance claims data from UnitedHealthcare, a database containing medical and prescription claim information as well as patient demographics. Because researchers used pharmacy dispensing records, they were able to include women 15 to 44 years old who had received at least one prescription for the contraceptive patch or a norgestimate-containing OC with 35 μg of ethinyl estradiol.

Unlike the studies by Jick and colleagues, the study by Cole and associates considered all women eligible, even if they had used OCs in the past. Cases of VTE, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were abstracted from this group, identified from insurance claim information, and confirmed by chart review. Review of medical records is an important strength of this study; no such review was done in the studies by Jick and colleagues. Four controls were matched to each case, by age and duration of contraceptive use.

(This study was commissioned in conjunction with both the FDA and Johnson & Johnson, makers of the contraceptive patch, but researchers had full control over the data and results and were not required to consult with Johnson & Johnson when reporting findings.)

There were 49,048 woman-years of exposure to the patch and 202,344 woman-years of exposure to the pill, with an incidence of VTE of 40.8 and 18.3 for every 100,000 woman-years in patch and pill users, respectively. The incidence of AMI was 6.1 and 3.5 for every 100,000 woman-years in patch and pill users, respectively. No ischemic strokes were noted in patch users.

The adjusted incidence ratio for VTE in patch users compared with pill users was 2.2, and for AMI it was 1.8. Following publication of this study, the FDA issued a statement in January of this year that women using the patch face an increased risk of VTE, compared with women using the pill. Package labeling was changed to reflect this heightened risk.

Reasons for different findings

The studies by Jick and colleagues and Cole and associates present very different findings. The studies by Jick and colleagues give the impression that there is no increased risk of VTE in patch users compared with pill users, but the studies have significant flaws. First, Jick and colleagues do not confirm the diagnosis of VTE in the medical record. This is particularly problematic because the reported number of pulmonary emboli (PE) is very high, compared with the number of deep vein thromboses. The 2006 study found 42 cases of PE and only 26 cases of deep vein thrombosis. Because the latter is more common than PE, this could indicate that deep vein thrombosis was underdiagnosed.

Another shortcoming is that Jick and colleagues included only nonfatal thromboembolic events, which may mean that they missed many cases of fatal VTE because they were not looking for this information. The inclusion of new initiators only also may have skewed the data. This would mean that former users of an OC may have been included in the patch group but were ineligible for inclusion in the pill group. This may bias the data toward experienced hormonal contraceptive users in the patch group, thereby falsely lowering the VTE rate.

The study by Cole and associates also has limitations. It included long-term users of hormonal contraceptives in both the patch and the OC groups, which may bias the data toward lower rates of VTE, AMI, and stroke for the same reasons cited above. One would assume that this bias was corrected, because prior use was allowed in both groups, making the bias equally distributed, but there is no way to confirm this with any degree of certainty.

All three studies have some flaws in common

All three studies used prescription information to determine exposure, but there is no guarantee that the women who filled the prescriptions actually used the agents. Patients given drug samples by their clinicians were overlooked because these samples are not tracked through pharmacy data.

Because the data were collected from insurance claims information of privately insured patients, it is impossible to generalize these findings to the general population. We cannot use the findings to determine whether the same results would be seen in uninsured women or women insured through nonprivate programs such as Medicaid or the Veterans Administration.

So what’s the bottom line?

Health-care providers should be cautious about citing these studies as “evidence” when advising patients about the risk of VTE while using the patch. The twofold increased risk of VTE observed in patch users and the almost twofold increased risk of AMI observed by Cole and associates cannot be completely ignored, however, particularly because this study was better designed than those by Jick and colleagues.

It is more important to remember that the incidence of VTE in patch users is extremely low. If a patient has been using the patch, is happy with the method, and has had no adverse effects, there is no reason, based on these findings, to discontinue it. When counseling new initiators, the best that can be done is to explain the potential risks and side effects associated with the method and allow the patient to make an informed choice using the information that is available.

If the increased risk of VTE is accurate, it would still be equal to or lower than the risk during pregnancy. A recent review found the overall incidence of VTE in pregnancy or the postpartum period to be 200 for every 100,000 woman-years.7

In a pooled analysis of the two studies of the contraceptive patch by Jick and colleagues and the one study by Cole and associates, the overall and method failure rates through 13 cycles were 0.8% and 0.6%, respectively, representing 15 pregnancies.1

Subject weights were divided into deciles to determine the number of pregnancies per decile. Interestingly, that number does not appear to be evenly distributed. In deciles 1 through 9, which represent women who weigh up to 80 kg, the number of pregnancies was eight, whereas seven pregnancies occurred in the 10th decile, which represents women weighing more than 80 kg. Because the number of pregnancies in decile 10 is essentially equivalent to all of the other deciles combined, women who weigh more than 80 kg (176 lb) appear to be at increased risk of pregnancy. Five of the seven pregnancies in decile 10 occurred in women weighing more than 90 kg (198 lb).

No studies have directly explored the reasons for this relationship or looked at body mass index or body surface area in relation to efficacy of the patch. Further research is clearly needed.

How to counsel overweight women

It is imperative that patients who weigh more than 198 lb be informed that the pregnancy rate is higher than the rate quoted for the patch. It may even be reasonable to counsel women in that 10thdecile—who weigh more than 176 lb—about alternative forms of hormonal contraception that would be more effective for them than the patch.

Reference

1. Ziemen M, Guillebaud J, Weisberg E, Shangold GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW. Contraceptive efficacy and cycle control with the Ortho Evra/Evra transdermal system: the analysis of pooled data. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 Suppl 2):S13-S18.

Why don’t American women choose long-acting reversible contraception?

Do American women not want to use long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), or are we, as providers, failing to properly educate them about its benefits?

The ParaGard copper IUD, the Mirena levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNGIUS), and the Implanon etonorgestrel contraceptive implant are all highly effective, convenient, long-duration, and reversible (FIGURE). Despite substantial evidence indicating that these methods are well tolerated and highly effective, only about 2% of American women are choosing them to prevent pregnancy.1 This rate lags far behind other countries in IUD utilization. In contrast, more than 50% of contraceptive users in China and Egypt are using intrauterine contraception.8

FIGURE

Copper IUD is effective for 12 years or longer

The copper IUD is FDA-approved for 10 years of use, although studies continue to support its continued efficacy for 12 years or longer.9 The 1-year perfect-use failure rate is 0.6%, and the typical use failure rate is 0.5% to 0.8%.10 The total failure rate over 12 years is 2.2%.9

Benefits. The copper IUD does not increase the risk of intrauterine infection and is safe to place in nulliparous patients.11 It is an excellent choice for women who clearly prefer to have monthly menses and for women who have personal or medical contraindications to hormonal birth control. Women using this method of birth control can expect excellent efficacy, rapid reversibility, and minimal side effects.

Adverse effects. The most common adverse events in copper IUD users are heavier menses and dysmenorrhea. Approximately 4.5% of women discontinue the copper IUD in the first year of use because of these particular side effects.12

LNG-IUS: Highly effective, with important noncontraceptive benefits

This method of birth control is comparable to the copper IUD in terms of efficacy and tolerability. It is FDA-approved for 5 years of use, with a cumulative 5-year failure rate of 0.7 for every 100 women.13 One small study demonstrated that this method is potentially effective up to 7 years, with a 1.1% pregnancy rate.11 With perfect use, the first-year pregnancy rate is 0.1% to 0.2%.14

Benefits. The progestin component provides noncontraceptive benefits, including a reduction in menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea,15 treatment of endometrial hyperplasia16 and endometrial cancer,17 endometrial protection in women using tamoxifen,18 treatment of endometriosis,19 and protection from pelvic inflammatory disease.20

Adverse effects. The primary disadvantage of this device is a change in bleeding pattern in some women, who may experience irregular spotting, primarily in the first 3 to 6 months.21 About 20% of users will become amenorrheic by 12 months of use, a feature that is highly desirable for many, but troubling to some.

Implant is essentially 100% effective

The newest LARC device is the etonorgestrel implant, which was approved by the FDA in July 2006. The single-rod implant is typically placed in the subcuticular tissue of the non-dominant arm, although placement in the dominant arm is fine if the patient prefers.

Benefits. In a 3-year study involving 635 subjects, no pregnancies were reported.22 The reported Pearl index of 0.38 pregnancies for every 100,000 woman-years of use relates to pregnancies that occurred shortly after discontinuation rather than during actual use. These studies included only women below 130% of their ideal body weight who were not using liver enzyme-inducing medications. The pregnancy rate in women who use such medications, or weigh above 130% of their ideal body weight, is unknown. Postmarketing surveillance has reported some pregnancies, as would be expected. The device is easily inserted and easily removed as long as 3 years later.

Adverse effects. The primary adverse effect of this implant is bleeding disturbances; discontinuation was usually due to this side effect.22 The cumulative discontinuation rate was 10% at 6 months, 20% at 12 months, 31% at 2 years, and 32.2% at 3 years.22

Training required. FDA approval included a stipulation that practitioners complete company-sponsored training (www.implanonusa.com) to insert and remove the device.

Overall benefits include minimal side effects, low cost

All LARC methods provide excellent protection against pregnancy (equal to or better than sterilization), have minimal side effects, and are rapidly reversible. They are also appropriate for women in whom combination hormonal contraception is contraindicated, such as smokers older than 35 years and women who have had VTE.

A final and important advantage: These methods are more cost-effective than other contraceptive methods, including combination OCs. They may require a higher initial investment, but the LNG-IUS and copper IUD are the least costly methods of contraception over 5 years of use.23

As providers continue to educate themselves and help women gain a better understanding of which methods are truly highly effective, they will likely begin to recommend LARC more often. Use of these devices has the potential to significantly decrease the high rate of unintended pregnancy.

Authors’ note: The figure at right depicts how the efficacy and convenience of contraceptive options rise (and side effects fall) along a continuum. LARC methods are “high up the ladder”—an observation that serves as food for thought as we counsel patients about what methods of birth control are best for them.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

We’ve heard that troubling statistic: Approximately 50% of pregnancies in the United States are unintended. But did you know that one half of those unintended pregnancies occur in women who were using some form of birth control at the time of conception?1 Such pregnancies are due to discontinuation of the method, incorrect use, or method failure.2 The focus of this article is contraceptive counseling, with special attention to:

- which methods of combination hormonal contraception women prefer

- the controversy surrounding the contraceptive patch in regard to thromboembolic disease

- long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the intrauterine device (IUD) and the contraceptive implant, with an emphasis on how LARC is of benefit to both the patient and society.

The ultimate goal of good contraceptive counseling? To help women choose the easiest and most effective method with the fewest side effects.

In head-to-head comparison, women preferred the ring to the patch

Creinin MD, Meyn LA, Borgatta L, et al. Multicenter comparison of the contraceptive ring and patch. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:267–277.

The ethinyl estradiol/etonogestril vaginal ring (NuvaRing) and the ethinyl estradiol/norelgestromin patch (OrthoEvra)—both approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001—are the only nonoral forms of combined hormonal contraception on the market. These methods are said to increase patient compliance and, potentially, efficacy, because they are nondaily forms of contraception.

Until recently, these methods had been compared only with the combination oral contraceptive (OC), but a recent trial compared them directly to each other. At the conclusion of the study, 71% of ring users and 26.5% of patch users planned to continue using the assigned method (P<.001).

This information should aid clinicians in counseling women about which combination hormonal method to choose.

Participants started out using the OC

The multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing the patch and ring included 479 women who were using, and happy with, the combination OC. After rating their satisfaction with the OC, women were randomized to the patch or ring and given 3 months’ worth of product. Follow-up involved only two telephone calls and one visit at the end of the third cycle, because this degree of monitoring was thought to mimic clinical practice.

The percentages of women who completed three cycles of their assigned product were 94.6% and 88.2% in the ring and patch groups, respectively (P=.03). The most common reasons for early discontinuation in the ring group were discomfort and adverse effects. In the patch group, the most common reasons were adverse effects, skin irritation, and adherence problems.

Even after adjusting for age, education, and whether an OC was actively being used at the time the study began, patch users were twice as likely to discontinue the patch at the end of three cycles and seven times more likely to state that they did not want to continue the patch.

Adverse effects were greater than with the pill

Women switching from pill to patch were significantly more likely to report breast pain, nausea, skin rash, longer menstrual bleeding, and menstrual pain than women who switched from the pill to the ring (P<.001).

Women who switched from the pill to the ring were more likely to experience vaginal discharge (P=.003) and a larger amount of vaginal discharge than patch users (P<.001).

These findings are similar to those of previous studies that compared the patch with the pill, noting that breast discomfort, application-site reaction, and dysmenorrhea were more common in patch than pill users.3 Earlier studies also found the ring to be associated with complaints of vaginal discharge.4,5

Findings may not be generalizable

The most important finding from this direct comparison is the difference in patient satisfaction between groups. Visual analog scales showed that women using the ring were happier with the ring than with the pill, whereas women using the patch were happier with the pill than with the patch (P<.001). Questionnaires revealed that women were more satisfied with the ring than they were with the patch, and were more likely to recommend the ring than the patch to a friend (P<.001).

Based on continuation rates, patient satisfaction, and adverse-effect profiles, women in this study clearly preferred the ring to the pill, and the pill to the patch. When using this information to counsel patients, however, it is important to recall that this population was specific. The women had been using an OC, with which they were happy. This study cannot necessarily be generalized to women who are just initiating combination hormonal contraception, but it can be helpful in counseling a patient who may want to switch from an OC to a method that involves nondaily dosing.

Does the contraceptive patch raise the risk of thromboembolism?

Jick SS, Kaye JA, Russman S, Jick H. Risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using a contraceptive patch and oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:223–228.

Jick S, Kaye JA, Li L, Jick H. Further results on the risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in users of the contraceptive transdermal patch compared to users of oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2007;76:4–7.

Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, Walker AM. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):339–346.

Both the media and regulatory agencies have raised concerns about whether the contraceptive patch heightens the risk of thromboembolism and is less effective in women above a certain body weight.

The controversy surrounding thromboembolic disease stems from a pharmacokinetics study by van den Heuvel and colleagues that compared serum ethinyl estradiol levels in users of the patch, vaginal ring, and a combination OC containing 30 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 150 μg of levonorgestrel.6 Women randomized to the patch had serum ethinyl estradiol levels 1.6 times higher than women randomized to an OC, and 3.4 times higher than women randomized to the ring.

These findings led the FDA to update package labeling of the patch to warn health-care providers and patients that the patch exposes women to 60% more estrogen and may increase the risk of thromboembolic events. Oddly, the FDA did not require any labeling change to combination OCs to indicate that they contain up to twice as much estrogen as the contraceptive ring.

A set of studies finds no elevated risk

Although the study by van den Heuvel and associates raised the possibility of increased blood clots in patch users, no association between the two had been corroborated at the time it was published.6 Since then, three epidemiological studies have explored the potential link between thromboembolic events and use of the patch.

In the first of these studies, Jick and colleagues used the PharMetrics database to extract data on users of the patch and norg-estimate-containing OCs. This database contains drug prescription information, patient demographic data, and ICD-9 billing codes submitted by managed care health plans. A nested case-control study design was used to compare patch and pill users and control for confounding variables.

The base population was women 15 to 44 years old who were new users of the patch or a norgestimate-containing OC. A thromboembolic event was diagnosed if the patient’s record included a diagnosis code for pulmonary embolus, deep vein thrombosis, or an emergency room visit or diagnostic testing indicating venous thromboembolism (VTE). These diagnosis codes, combined with the prescription of long-term anticoagulation therapy, strengthened the identification of cases. As many as four controls were selected for each case.

The 215,769 women included in this study contributed 147,323 woman-years of exposure to the drugs. There were 31 and 37 cases of VTE identified in the patch and pill groups, respectively, with an incidence of 52.8 for every 100,000 woman-years in the patch group and 41.8 for every 100,000 woman-years in the pill group and an unadjusted, matched odds ratio of VTE in patch versus pill users of 0.9. When the data were adjusted for duration of drug exposure, the odds ratio did not change.

A follow-up study by Jick and associates, published in 2007, had the same study design and included 17 additional months of data. Another 56 cases of VTE were diagnosed. The odds ratio for patch users, compared with pill users, was 1.1. When data from the two studies were combined, 73 and 51 total cases of VTE had occurred in the pill and patch groups, respectively. The overall odds ratio was 1.0.

A third study finds significantly heightened risk

Cole and associates studied insurance claims data from UnitedHealthcare, a database containing medical and prescription claim information as well as patient demographics. Because researchers used pharmacy dispensing records, they were able to include women 15 to 44 years old who had received at least one prescription for the contraceptive patch or a norgestimate-containing OC with 35 μg of ethinyl estradiol.

Unlike the studies by Jick and colleagues, the study by Cole and associates considered all women eligible, even if they had used OCs in the past. Cases of VTE, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were abstracted from this group, identified from insurance claim information, and confirmed by chart review. Review of medical records is an important strength of this study; no such review was done in the studies by Jick and colleagues. Four controls were matched to each case, by age and duration of contraceptive use.

(This study was commissioned in conjunction with both the FDA and Johnson & Johnson, makers of the contraceptive patch, but researchers had full control over the data and results and were not required to consult with Johnson & Johnson when reporting findings.)

There were 49,048 woman-years of exposure to the patch and 202,344 woman-years of exposure to the pill, with an incidence of VTE of 40.8 and 18.3 for every 100,000 woman-years in patch and pill users, respectively. The incidence of AMI was 6.1 and 3.5 for every 100,000 woman-years in patch and pill users, respectively. No ischemic strokes were noted in patch users.

The adjusted incidence ratio for VTE in patch users compared with pill users was 2.2, and for AMI it was 1.8. Following publication of this study, the FDA issued a statement in January of this year that women using the patch face an increased risk of VTE, compared with women using the pill. Package labeling was changed to reflect this heightened risk.

Reasons for different findings

The studies by Jick and colleagues and Cole and associates present very different findings. The studies by Jick and colleagues give the impression that there is no increased risk of VTE in patch users compared with pill users, but the studies have significant flaws. First, Jick and colleagues do not confirm the diagnosis of VTE in the medical record. This is particularly problematic because the reported number of pulmonary emboli (PE) is very high, compared with the number of deep vein thromboses. The 2006 study found 42 cases of PE and only 26 cases of deep vein thrombosis. Because the latter is more common than PE, this could indicate that deep vein thrombosis was underdiagnosed.

Another shortcoming is that Jick and colleagues included only nonfatal thromboembolic events, which may mean that they missed many cases of fatal VTE because they were not looking for this information. The inclusion of new initiators only also may have skewed the data. This would mean that former users of an OC may have been included in the patch group but were ineligible for inclusion in the pill group. This may bias the data toward experienced hormonal contraceptive users in the patch group, thereby falsely lowering the VTE rate.

The study by Cole and associates also has limitations. It included long-term users of hormonal contraceptives in both the patch and the OC groups, which may bias the data toward lower rates of VTE, AMI, and stroke for the same reasons cited above. One would assume that this bias was corrected, because prior use was allowed in both groups, making the bias equally distributed, but there is no way to confirm this with any degree of certainty.

All three studies have some flaws in common

All three studies used prescription information to determine exposure, but there is no guarantee that the women who filled the prescriptions actually used the agents. Patients given drug samples by their clinicians were overlooked because these samples are not tracked through pharmacy data.

Because the data were collected from insurance claims information of privately insured patients, it is impossible to generalize these findings to the general population. We cannot use the findings to determine whether the same results would be seen in uninsured women or women insured through nonprivate programs such as Medicaid or the Veterans Administration.

So what’s the bottom line?

Health-care providers should be cautious about citing these studies as “evidence” when advising patients about the risk of VTE while using the patch. The twofold increased risk of VTE observed in patch users and the almost twofold increased risk of AMI observed by Cole and associates cannot be completely ignored, however, particularly because this study was better designed than those by Jick and colleagues.

It is more important to remember that the incidence of VTE in patch users is extremely low. If a patient has been using the patch, is happy with the method, and has had no adverse effects, there is no reason, based on these findings, to discontinue it. When counseling new initiators, the best that can be done is to explain the potential risks and side effects associated with the method and allow the patient to make an informed choice using the information that is available.

If the increased risk of VTE is accurate, it would still be equal to or lower than the risk during pregnancy. A recent review found the overall incidence of VTE in pregnancy or the postpartum period to be 200 for every 100,000 woman-years.7

In a pooled analysis of the two studies of the contraceptive patch by Jick and colleagues and the one study by Cole and associates, the overall and method failure rates through 13 cycles were 0.8% and 0.6%, respectively, representing 15 pregnancies.1

Subject weights were divided into deciles to determine the number of pregnancies per decile. Interestingly, that number does not appear to be evenly distributed. In deciles 1 through 9, which represent women who weigh up to 80 kg, the number of pregnancies was eight, whereas seven pregnancies occurred in the 10th decile, which represents women weighing more than 80 kg. Because the number of pregnancies in decile 10 is essentially equivalent to all of the other deciles combined, women who weigh more than 80 kg (176 lb) appear to be at increased risk of pregnancy. Five of the seven pregnancies in decile 10 occurred in women weighing more than 90 kg (198 lb).

No studies have directly explored the reasons for this relationship or looked at body mass index or body surface area in relation to efficacy of the patch. Further research is clearly needed.

How to counsel overweight women

It is imperative that patients who weigh more than 198 lb be informed that the pregnancy rate is higher than the rate quoted for the patch. It may even be reasonable to counsel women in that 10thdecile—who weigh more than 176 lb—about alternative forms of hormonal contraception that would be more effective for them than the patch.

Reference

1. Ziemen M, Guillebaud J, Weisberg E, Shangold GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW. Contraceptive efficacy and cycle control with the Ortho Evra/Evra transdermal system: the analysis of pooled data. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 Suppl 2):S13-S18.

Why don’t American women choose long-acting reversible contraception?

Do American women not want to use long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), or are we, as providers, failing to properly educate them about its benefits?

The ParaGard copper IUD, the Mirena levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNGIUS), and the Implanon etonorgestrel contraceptive implant are all highly effective, convenient, long-duration, and reversible (FIGURE). Despite substantial evidence indicating that these methods are well tolerated and highly effective, only about 2% of American women are choosing them to prevent pregnancy.1 This rate lags far behind other countries in IUD utilization. In contrast, more than 50% of contraceptive users in China and Egypt are using intrauterine contraception.8

FIGURE

Copper IUD is effective for 12 years or longer

The copper IUD is FDA-approved for 10 years of use, although studies continue to support its continued efficacy for 12 years or longer.9 The 1-year perfect-use failure rate is 0.6%, and the typical use failure rate is 0.5% to 0.8%.10 The total failure rate over 12 years is 2.2%.9

Benefits. The copper IUD does not increase the risk of intrauterine infection and is safe to place in nulliparous patients.11 It is an excellent choice for women who clearly prefer to have monthly menses and for women who have personal or medical contraindications to hormonal birth control. Women using this method of birth control can expect excellent efficacy, rapid reversibility, and minimal side effects.

Adverse effects. The most common adverse events in copper IUD users are heavier menses and dysmenorrhea. Approximately 4.5% of women discontinue the copper IUD in the first year of use because of these particular side effects.12

LNG-IUS: Highly effective, with important noncontraceptive benefits

This method of birth control is comparable to the copper IUD in terms of efficacy and tolerability. It is FDA-approved for 5 years of use, with a cumulative 5-year failure rate of 0.7 for every 100 women.13 One small study demonstrated that this method is potentially effective up to 7 years, with a 1.1% pregnancy rate.11 With perfect use, the first-year pregnancy rate is 0.1% to 0.2%.14

Benefits. The progestin component provides noncontraceptive benefits, including a reduction in menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea,15 treatment of endometrial hyperplasia16 and endometrial cancer,17 endometrial protection in women using tamoxifen,18 treatment of endometriosis,19 and protection from pelvic inflammatory disease.20

Adverse effects. The primary disadvantage of this device is a change in bleeding pattern in some women, who may experience irregular spotting, primarily in the first 3 to 6 months.21 About 20% of users will become amenorrheic by 12 months of use, a feature that is highly desirable for many, but troubling to some.

Implant is essentially 100% effective

The newest LARC device is the etonorgestrel implant, which was approved by the FDA in July 2006. The single-rod implant is typically placed in the subcuticular tissue of the non-dominant arm, although placement in the dominant arm is fine if the patient prefers.

Benefits. In a 3-year study involving 635 subjects, no pregnancies were reported.22 The reported Pearl index of 0.38 pregnancies for every 100,000 woman-years of use relates to pregnancies that occurred shortly after discontinuation rather than during actual use. These studies included only women below 130% of their ideal body weight who were not using liver enzyme-inducing medications. The pregnancy rate in women who use such medications, or weigh above 130% of their ideal body weight, is unknown. Postmarketing surveillance has reported some pregnancies, as would be expected. The device is easily inserted and easily removed as long as 3 years later.

Adverse effects. The primary adverse effect of this implant is bleeding disturbances; discontinuation was usually due to this side effect.22 The cumulative discontinuation rate was 10% at 6 months, 20% at 12 months, 31% at 2 years, and 32.2% at 3 years.22

Training required. FDA approval included a stipulation that practitioners complete company-sponsored training (www.implanonusa.com) to insert and remove the device.

Overall benefits include minimal side effects, low cost

All LARC methods provide excellent protection against pregnancy (equal to or better than sterilization), have minimal side effects, and are rapidly reversible. They are also appropriate for women in whom combination hormonal contraception is contraindicated, such as smokers older than 35 years and women who have had VTE.

A final and important advantage: These methods are more cost-effective than other contraceptive methods, including combination OCs. They may require a higher initial investment, but the LNG-IUS and copper IUD are the least costly methods of contraception over 5 years of use.23

As providers continue to educate themselves and help women gain a better understanding of which methods are truly highly effective, they will likely begin to recommend LARC more often. Use of these devices has the potential to significantly decrease the high rate of unintended pregnancy.

Authors’ note: The figure at right depicts how the efficacy and convenience of contraceptive options rise (and side effects fall) along a continuum. LARC methods are “high up the ladder”—an observation that serves as food for thought as we counsel patients about what methods of birth control are best for them.

1. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:24-29, 46.

2. Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Long S. Unintended pregnancies and use, misuse and discontinuation of oral contraceptives. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:355-360.

3. Sibai BM, Odlind V, Meador ML, Shangold GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW. A comparative and pooled analysis of the safety and tolerability of the contraceptive patch (Ortho Evra/Evra). Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 Suppl 2):S19-S26.

4. Arhendt HJ, Nisand I, Bastianelli C, et al. Efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of the combined contraceptive ring, NuvaRing, compared with an oral contraceptive containing 30 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone. Contraception. 2006;74:451-457.

5. Oddson K, Leifels-Fischer B, de Melo NR, et al. Efficacy and safety of a contraceptive vaginal ring (NuvaRing) compared with a combined oral contraceptive:a 1-year randomized trial. Contraception. 2005;71:176-182.

6. van den Heuvel MW, van Bragt AJ, Alnabawy AK, Kaptein MC. Comparison of ethinylestradiol pharmacokinetics in three hormonal contraceptive formulations: The vaginal ring, the transdermal patch and an oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2005;72:168-174.

7. Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum:a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697-706.

8. d’Arcangues C. Worldwide use of intrauterine devices for contraception. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl):S2-S7.

9. Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56:341-352.

10. Sivin I, Schmidt F. Effectiveness of IUDs: a review. Contraception. 1987;36:55-84.

11. Rivera R, Chen-Mok M, McMullen S. Analysis of client characteristics that may affect early discontinuation of the TCu-380A IUD. Contraception. 1999;60:155-160.

12. Hubacher D, Lara-Ricalde R, Taylor DJ, Guerra Infante F, Guzmán-Rodríguez R. Use of copper intrauterine devices and the risk of tubal infertility among nulligravid women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:561-567.

13. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In:Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 18th ed. New York: Ardent Media, Inc.;2004:495-530.

14. Sivin I, Stern J. Healthduring prolonged use of levonorgestrel 20 micrograms/d and the copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devices: a multicenter study. International Committee for Contraception Research (ICCR). Fertil Steril. 1994;61:70-77.

15. Kadir RA, Chi C. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system: bleeding disorders and anticoagulant therapy. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl):S123-S129.

16. Wildemeersch D, Dhont M. Treatment of non-atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1297-1298.

17. Dhar KK, NeedhiRajan T, Koslowski M, Woolas RP. Is levonorgestrel intrauterine system effective for treatment of early endometrial cancer? Report of four cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:924-927.

18. Gardner FJ, Konje JC, Abrams KR, et al. Endometrial protection from tamoxifen-stimulated changes by a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system:a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:1711-1717.

19. Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy, side-effects and continuation rates of women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intra-uterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel):a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:789-793.

20. Toivonen J, Luukkainen T, Allonen H. Protective effect of intrauterine release of levonorgestrel on pelvic infection: three years’comparative experience of levonorgestrel-and copper-releasing intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:261-264.

21. Backman T, Huhtala S, Blom T, Luoto R, Rauramo I, Koskenvuo M. Length of use and symptoms associated with premature removal of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system:a nationwide study of 17,360 users. BJOG. 2000;107:335-339.

22. Croxatto HB. Clinical profile of Implanon:a single-rod etonorgestrel contraceptive implant. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2000;5(Suppl 2):21-28.

23. Chiou CF, Trussell J, Reyes E, et al. Economic analysis of contraceptives for women. Contraception. 2003;68:3-10.

1. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:24-29, 46.

2. Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Long S. Unintended pregnancies and use, misuse and discontinuation of oral contraceptives. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:355-360.

3. Sibai BM, Odlind V, Meador ML, Shangold GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW. A comparative and pooled analysis of the safety and tolerability of the contraceptive patch (Ortho Evra/Evra). Fertil Steril. 2002;77(2 Suppl 2):S19-S26.

4. Arhendt HJ, Nisand I, Bastianelli C, et al. Efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of the combined contraceptive ring, NuvaRing, compared with an oral contraceptive containing 30 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone. Contraception. 2006;74:451-457.

5. Oddson K, Leifels-Fischer B, de Melo NR, et al. Efficacy and safety of a contraceptive vaginal ring (NuvaRing) compared with a combined oral contraceptive:a 1-year randomized trial. Contraception. 2005;71:176-182.

6. van den Heuvel MW, van Bragt AJ, Alnabawy AK, Kaptein MC. Comparison of ethinylestradiol pharmacokinetics in three hormonal contraceptive formulations: The vaginal ring, the transdermal patch and an oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2005;72:168-174.

7. Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum:a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697-706.

8. d’Arcangues C. Worldwide use of intrauterine devices for contraception. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl):S2-S7.

9. Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56:341-352.

10. Sivin I, Schmidt F. Effectiveness of IUDs: a review. Contraception. 1987;36:55-84.

11. Rivera R, Chen-Mok M, McMullen S. Analysis of client characteristics that may affect early discontinuation of the TCu-380A IUD. Contraception. 1999;60:155-160.

12. Hubacher D, Lara-Ricalde R, Taylor DJ, Guerra Infante F, Guzmán-Rodríguez R. Use of copper intrauterine devices and the risk of tubal infertility among nulligravid women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:561-567.

13. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In:Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 18th ed. New York: Ardent Media, Inc.;2004:495-530.

14. Sivin I, Stern J. Healthduring prolonged use of levonorgestrel 20 micrograms/d and the copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devices: a multicenter study. International Committee for Contraception Research (ICCR). Fertil Steril. 1994;61:70-77.

15. Kadir RA, Chi C. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system: bleeding disorders and anticoagulant therapy. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl):S123-S129.

16. Wildemeersch D, Dhont M. Treatment of non-atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1297-1298.

17. Dhar KK, NeedhiRajan T, Koslowski M, Woolas RP. Is levonorgestrel intrauterine system effective for treatment of early endometrial cancer? Report of four cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:924-927.

18. Gardner FJ, Konje JC, Abrams KR, et al. Endometrial protection from tamoxifen-stimulated changes by a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system:a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:1711-1717.

19. Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy, side-effects and continuation rates of women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intra-uterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel):a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:789-793.

20. Toivonen J, Luukkainen T, Allonen H. Protective effect of intrauterine release of levonorgestrel on pelvic infection: three years’comparative experience of levonorgestrel-and copper-releasing intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:261-264.

21. Backman T, Huhtala S, Blom T, Luoto R, Rauramo I, Koskenvuo M. Length of use and symptoms associated with premature removal of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system:a nationwide study of 17,360 users. BJOG. 2000;107:335-339.

22. Croxatto HB. Clinical profile of Implanon:a single-rod etonorgestrel contraceptive implant. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2000;5(Suppl 2):21-28.

23. Chiou CF, Trussell J, Reyes E, et al. Economic analysis of contraceptives for women. Contraception. 2003;68:3-10.