User login

From the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Existing research has demonstrated overall low rates of residents establishing care with a primary care physician (PCP). We conducted a survey-based study to better understand chronic illness, PCP utilization, and prescription medication use patterns in resident physician populations.

- Methods: In 2017, we invited internal and family medicine trainees from a convenience sample of U.S. residency programs to participate in a survey. We compared the characteristics of residents who had established care with a PCP to those who had not.

- Results: The response rate was 45% (348/766 residents). The majority (n = 205, 59%) of respondents stated they had established care with a PCP primarily for routine preventative care (n = 159, 79%) and access in the event of an emergency (n = 132, 66%). However, 31% (n = 103) denied having had a wellness visit in over 3 years. Nearly a quarter of residents (n = 77, 23%) reported a chronic medical illness and 14% (n = 45) reported a preexisting mental health condition prior to residency. One-third (n = 111, 33%) reported taking a long-term prescription medication. Compared to residents who had not established care, those with a PCP (n = 205) more often reported a chronic condition (P < 0.001), seeing a subspecialist (P = 0.01), or taking long-term prescription medications (P < 0.001). One in 5 (n = 62,19%) respondents reported receiving prescriptions for an acute illness from an individual with whom they did not have a doctor-patient relationship.

- Conclusion: Medical residents have a substantial burden of chronic illness that may not be met through interactions with PCPs. Further understanding their medical needs and barriers to accessing care is necessary to ensure trainee well-being.

Keywords: Medical education-graduate, physician behavior, survey research, access to care.

Although internal medicine (IM) and family medicine (FM) residents must learn to provide high-quality primary care to their patients, little is known about whether they appropriately access such care themselves. Resident burnout and resilience has received attention [1,2], but there has been limited focus on understanding the burden of chronic medical and mental illness among residents. In particular, little is known about whether residents access primary care physicians (PCPs)—for either acute or chronic medical needs—and about resident self-medication practices.

Residency is often characterized by a life-changing geographic relocation. Even residents who do not relocate may still need to establish care with a new PCP due to health insurance or loss of access to a student clinic [3]. Establishing primary care with a new doctor typically requires scheduling a new patient visit, often with a wait time of several days to weeks [4,5]. Furthermore, lack of time, erratic schedules, and concerns about privacy and the stigma of being ill as a physician are barriers to establishing care [6-8]. Individuals who have not established primary care may experience delays in routine preventative health services, screening for chronic medical and mental health conditions, as well as access to care during acute illnesses [9,10]. Worse, they may engage in potentially unsafe practices, such as having colleagues write prescriptions for them, or even self-prescribing [8,11,12].

Existing research has demonstrated overall low rates of residents establishing care with a PCP [6–8,13]. However, these studies have either been limited to large academic centers or conducted outside the United States. Improving resident well-being may prove challenging without a clear understanding of current primary care utilization practices, the burden of chronic illness among residents, and patterns of prescription medication use and needs. Therefore, we conducted a survey-based study to understand primary care utilization and the burden of chronic illness among residents. We also assessed whether lack of primary care is associated with potentially risky behaviors, such as self-prescribing of medications.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

The survey was distributed to current residents at IM and FM programs within the United States in 2017. Individual programs were recruited by directly contacting program directors or chief medical residents via email. Rather than contacting sites directly through standard templated emails, we identified programs both through personal contacts as well as the Electronic Residency Application Service list of accredited IM training programs. We elected to use this approach in order to increase response rates and to ensure that a sample representative of the trainee population was constructed. Programs were located in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and Pacific regions, and included small community-based programs and large academic centers.

Development of the Survey

The survey instrument was developed by the authors and reviewed by residents and PCPs at the University of Michigan to ensure relevance and comprehension of questions (The survey is available in the Appendix.). Once finalized, the survey was programmed into an online survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and pilot-tested before being disseminated to the sampling frame. Data collected in the survey included: respondent’s utilization of a PCP, burden of chronic illness, long-term prescription medications, prescribing source, and demographic characteristics.

Each participating program distributed the survey to their residents through an email containing an anonymous hyperlink. The survey was available for completion for 4 weeks. We asked participating programs to send email reminders to encourage participation. Participants were given the option of receiving a $10 Amazon gift card after completion. All responses were recorded anonymously. The study received a “not regulated” status by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM 00123888).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate results. Respondents were encouraged, but not required, to answer all questions. Therefore, the response rate for each question was calculated using the total number of responses for that question as the denominator. Bivariable comparisons were made using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical data. A P value < 0.05, with 2-sided alpha, was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

Of the 29 programs contacted, 10 agreed to participate within the study timeframe. Of 766 potential respondents, 348 (45%) residents answered the survey (Table 1). The majority of respondents (n = 276, 82%) were from IM programs. Respondents were from all training years as follows: postgraduate year 1 residents (PGY-1, or interns; n = 130, 39%), PGY-2 residents (n = 98, 29%), PGY-3 residents (n = 93, 28%), and PGY-4 residents (n = 12, 4%). Most respondents were from the South (n = 130, 39%) and Midwest (n = 123, 37%) regions, and over half (n = 179, 54%) were female. Most respondents (n = 285, 86%) stated that they did not have children. The majority (n = 236, 71%) were completing residency in an area where they had not previously lived for more than 1 year.

Primary Care Utilization

Among the 348 respondents, 59% (n = 205) reported having established care with a PCP. An additional 6% (n = 21) had established care with an obstetrician/gynecologist for routine needs (Table 2). The 2 most common reasons for establishing care with a PCP were routine primary care needs, including contraception (n = 159, 79%), and access to a physician in the event of an acute medical need (n = 132, 66%).

Among respondents who had established care with a PCP, most (n = 188, 94%) had completed at least 1 appointment. However, among these 188 respondents, 68% (n = 127) stated that they had not made an acute visit in more than 12 months. When asked about wellness visits, almost one third of respondents (n = 103, 31%) stated that they had not been seen for a wellness visit in the past 3 years.

Burden of Chronic Illness

Most respondents (n = 223, 67%) stated that they did not have a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency (Table 3). However, 23% (n = 77) of respondents stated that they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness prior to residency, and 14% (n = 45) indicated they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition prior to residency. Almost one fifth of respondents (n = 60, 18%) reported seeing a subspecialist for a medical illness, and 33% (n = 111) reported taking a long-term prescription medication. With respect to major medical issues, the majority of residents (n = 239, 72%) denied experiencing events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, or an emergency department (ED) visit during training.

[polldaddy:10116940]

Inappropriate Prescriptions

While the majority of respondents denied writing a prescription for themselves for an acute or chronic medical condition, almost one fifth (n = 62, 19%) had received a prescription for an acute medical need from a provider outside of a clinical relationship (ie, from someone other than their PCP or specialty provider). Notably, 5% (n = 15) reported that this had occurred at least 2 or 3 times in the past 12 months (Table 4). Compared to respondents not taking long-term prescription medications, respondents who were already taking long-term prescription medications more frequently reported inappropriately receiving chronic prescriptions outside of an established clinical relationship (n = 14, 13% vs. n = 14, 6%; P = 0.05) and more often self-prescribed medications for acute needs (n = 12, 11% vs. n = 7, 3%; P = 0.005).

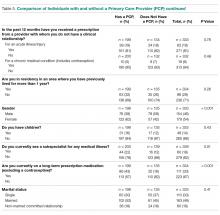

Comparison of Residents With and Without a PCP

Important differences were noted between residents who had a PCP versus those who did not (Table 5). For example, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP indicated they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness (n = 55, 28% vs. n = 22, 16%; P = 0.01) or a chronic mental health condition (n = 34, 17% vs. n = 11, 8%; P = 0.02) before residency. Additionally, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP (n = 70, 35% vs. n = 25, 18%; P = 0.001) reported experiencing medical events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, ED visit, or new diagnosis of a chronic medical illness during residency. Finally, a higher percentage of respondents with a PCP stated that they had visited a subspecialist for a medical illness (n = 44, 22% vs. n = 16,12%; P = 0.01) or were taking long-term prescription medications (n = 86, 43% vs. n = 25; 18%; P < 0.001). When comparing PGY-1 to PGY-2–PGY-4 residents, the former reported having established a medical relationship with a PCP significantly less frequently (n = 56, 43% vs. n = 142, 70%; P < 0.001).

Discussion

This survey-based study of medical residents across the United States suggests that a substantial proportion do not establish relationships with PCPs. Additionally, our data suggest that despite establishing care, few residents subsequently visited their PCP during training for wellness visits or routine care. Self-reported rates of chronic medical and mental health conditions were substantial in our sample. Furthermore, inappropriate self-prescription and the receipt of prescriptions outside of a medical relationship were also reported. These findings suggest that future studies that focus on the unique medical and mental health needs of physicians in training, as well as interventions to encourage care in this vulnerable period, are necessary.

We observed that most respondents that established primary care were female trainees. Although it is impossible to know with certainty, one hypothesis behind this discrepancy is that women routinely need to access preventative care for gynecologic needs such as pap smears, contraception, and potentially pregnancy and preconception counseling [14,15]. Similarly, residents with a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency established care with a local PCP at a significantly greater frequency than those without such diagnoses. While selection bias cannot be excluded, this finding suggests that illness is a driving factor in establishing care. There also appears to be an association between accessing the medical system (either for prescription medications or subspecialist care) and having established care with a PCP. Collectively, these data suggest that individuals without a compelling reason to access medical services might have barriers to accessing care in the event of medical needs or may not receive routine preventative care [9,10].

In general, we found that rates of reported inappropriate prescriptions were lower than those reported in prior studies where a comparable resident population was surveyed [8,12,16]. Inclusion of multiple institutions, differences in temporality, social desirability bias, and reporting bias might have influenced our findings in this regard. Surprisingly, we found that having a PCP did not influence likelihood of inappropriate prescription receipt, perhaps suggesting that this behavior reflects some degree of universal difficulty in accessing care. Alternatively, this finding might relate to a cultural tendency to self-prescribe among resident physicians. The fact that individuals on chronic medications more often both received and wrote inappropriate prescriptions suggests this problem might be more pronounced in individuals who take medications more often, as these residents have specific needs [12]. Future studies targeting these individuals thus appear warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample size was modest and the response rate of 45% was low. However, to our knowledge, this remains among the largest survey on this topic, and our response rate is comparable to similar trainee studies [8,11,13]. Second, we designed and created a novel survey for this study. While the questions were pilot-tested with users prior to dissemination, validation of the instrument was not performed. Third, since the study population was restricted to residents in fields that participate in primary care, our findings may not be generalizable to patterns of PCP use in other specialties [6].

These limitations aside, our study has important strengths. This is the first national study of its kind with specific questions addressing primary care access and utilization, prescription medication use and related practices, and the prevalence of medical conditions among trainees. Important differences in the rates of establishing primary care between male and female respondents, first- year and senior residents, and those with and without chronic disease suggest a need to target specific resident groups (males, interns, those without pre-existing conditions) for wellness-related interventions. Such interventions could include distribution of a list of local providers to first year residents, advanced protected time for doctor’s appointments, and safeguards to ensure health information is protected from potential supervisors. Future studies should also include residents from non-primary care oriented specialties such as surgery, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology to obtain results that are more generalizable to the resident population as a whole. Additionally, the rates of inappropriate prescriptions were not insignificant and warrant further evaluation of the driving forces behind these behaviors.

Conclusion

Medical residents have a substantial burden of chronic illness that may not be met through interactions with PCPs. More research into barriers that residents face while accessing care and an assessment of interventions to facilitate their access to care is important to promote trainee well-being. Without such direction and initiative, it may prove harder for physicians to heal themselves or those for whom they provide care.

Acknowledgments: We thank Suzanne Winter, the study coordinator, for her support with editing and formatting the manuscript, Latoya Kuhn for performing the statistical analysis and creating data tables, and Dr. Namita Sachdev and Dr. Renuka Tipirneni for providing feedback on the survey instrument. We also thank the involved programs for their participation.

Corresponding author: Vineet Chopra, NCRC 2800 Plymouth Rd., Bldg 16, 432, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, vineetc@med.umich.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Previous presentations: Results were presented at the Annual Michigan Medicine 2017 Internal Medicine Research Symposium.

1. Kassam A, Horton J, Shoimer I, Patten S. Predictors of well-being in resident physicians: a descriptive and psychometric study. J Grad Med Educ 2015;7:70–4.

2. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:358–67.

3. Burstin HR, Swartz K, O’Neil AC, et al. The effect of change of health insurance on access to care. Inquiry 1998;35:389–97.

4. Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Friedman AB, et al. Access to primary care appointments following 2014 insurance expansions. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:107–12.

5. Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, et al. Appointment availability after increases in Medicaid payments for primary care. N Engl J Med 2015;372:537–45.

6. Gupta G, Schleinitz MD, Reinert SE, McGarry KA. Resident physician preventive health behaviors and perspectives on primary care. R I Med J (2013) 2013;96:43–7.

7. Rosen IM, Christine JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:116-21.

8. Campbell S, Delva D. Physician do not heal thyself. Survey of personal health practices among medical residents. Can Fam Physician 2003;49:1121–7.

9. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502.

10. Weissman JS, Stern R, Fielding SL, et al. Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:325–31.

11. Guille C, Sen S. Prescription drug use and self-prescription among training physicians. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:371–2.

12. Roberts LW, Kim JP. Informal health care practices of residents: “curbside” consultation and self-diagnosis and treatment. Acad Psychiatry 2015;39:22-30.

13. Cohen JS, Patten S. Well-being in residency training: a survey examining resident physician satisfaction both within and outside of residency training and mental health in Alberta. BMC Med Educ 2005;5:21.

14. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Published March 2012. Accessed August 21, 2018.

15. Health Resources and Services Administration. Women’s preventative services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines2016/index.html. Updated October 2017. Accessed August 21, 2018.

16. Christie JD, Rosen IM, Bellini LM, et al. Prescription drug use and self-prescription among resident physicians. JAMA 1998;280(14):1253–5.

From the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Existing research has demonstrated overall low rates of residents establishing care with a primary care physician (PCP). We conducted a survey-based study to better understand chronic illness, PCP utilization, and prescription medication use patterns in resident physician populations.

- Methods: In 2017, we invited internal and family medicine trainees from a convenience sample of U.S. residency programs to participate in a survey. We compared the characteristics of residents who had established care with a PCP to those who had not.

- Results: The response rate was 45% (348/766 residents). The majority (n = 205, 59%) of respondents stated they had established care with a PCP primarily for routine preventative care (n = 159, 79%) and access in the event of an emergency (n = 132, 66%). However, 31% (n = 103) denied having had a wellness visit in over 3 years. Nearly a quarter of residents (n = 77, 23%) reported a chronic medical illness and 14% (n = 45) reported a preexisting mental health condition prior to residency. One-third (n = 111, 33%) reported taking a long-term prescription medication. Compared to residents who had not established care, those with a PCP (n = 205) more often reported a chronic condition (P < 0.001), seeing a subspecialist (P = 0.01), or taking long-term prescription medications (P < 0.001). One in 5 (n = 62,19%) respondents reported receiving prescriptions for an acute illness from an individual with whom they did not have a doctor-patient relationship.

- Conclusion: Medical residents have a substantial burden of chronic illness that may not be met through interactions with PCPs. Further understanding their medical needs and barriers to accessing care is necessary to ensure trainee well-being.

Keywords: Medical education-graduate, physician behavior, survey research, access to care.

Although internal medicine (IM) and family medicine (FM) residents must learn to provide high-quality primary care to their patients, little is known about whether they appropriately access such care themselves. Resident burnout and resilience has received attention [1,2], but there has been limited focus on understanding the burden of chronic medical and mental illness among residents. In particular, little is known about whether residents access primary care physicians (PCPs)—for either acute or chronic medical needs—and about resident self-medication practices.

Residency is often characterized by a life-changing geographic relocation. Even residents who do not relocate may still need to establish care with a new PCP due to health insurance or loss of access to a student clinic [3]. Establishing primary care with a new doctor typically requires scheduling a new patient visit, often with a wait time of several days to weeks [4,5]. Furthermore, lack of time, erratic schedules, and concerns about privacy and the stigma of being ill as a physician are barriers to establishing care [6-8]. Individuals who have not established primary care may experience delays in routine preventative health services, screening for chronic medical and mental health conditions, as well as access to care during acute illnesses [9,10]. Worse, they may engage in potentially unsafe practices, such as having colleagues write prescriptions for them, or even self-prescribing [8,11,12].

Existing research has demonstrated overall low rates of residents establishing care with a PCP [6–8,13]. However, these studies have either been limited to large academic centers or conducted outside the United States. Improving resident well-being may prove challenging without a clear understanding of current primary care utilization practices, the burden of chronic illness among residents, and patterns of prescription medication use and needs. Therefore, we conducted a survey-based study to understand primary care utilization and the burden of chronic illness among residents. We also assessed whether lack of primary care is associated with potentially risky behaviors, such as self-prescribing of medications.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

The survey was distributed to current residents at IM and FM programs within the United States in 2017. Individual programs were recruited by directly contacting program directors or chief medical residents via email. Rather than contacting sites directly through standard templated emails, we identified programs both through personal contacts as well as the Electronic Residency Application Service list of accredited IM training programs. We elected to use this approach in order to increase response rates and to ensure that a sample representative of the trainee population was constructed. Programs were located in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and Pacific regions, and included small community-based programs and large academic centers.

Development of the Survey

The survey instrument was developed by the authors and reviewed by residents and PCPs at the University of Michigan to ensure relevance and comprehension of questions (The survey is available in the Appendix.). Once finalized, the survey was programmed into an online survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and pilot-tested before being disseminated to the sampling frame. Data collected in the survey included: respondent’s utilization of a PCP, burden of chronic illness, long-term prescription medications, prescribing source, and demographic characteristics.

Each participating program distributed the survey to their residents through an email containing an anonymous hyperlink. The survey was available for completion for 4 weeks. We asked participating programs to send email reminders to encourage participation. Participants were given the option of receiving a $10 Amazon gift card after completion. All responses were recorded anonymously. The study received a “not regulated” status by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM 00123888).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate results. Respondents were encouraged, but not required, to answer all questions. Therefore, the response rate for each question was calculated using the total number of responses for that question as the denominator. Bivariable comparisons were made using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical data. A P value < 0.05, with 2-sided alpha, was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

Of the 29 programs contacted, 10 agreed to participate within the study timeframe. Of 766 potential respondents, 348 (45%) residents answered the survey (Table 1). The majority of respondents (n = 276, 82%) were from IM programs. Respondents were from all training years as follows: postgraduate year 1 residents (PGY-1, or interns; n = 130, 39%), PGY-2 residents (n = 98, 29%), PGY-3 residents (n = 93, 28%), and PGY-4 residents (n = 12, 4%). Most respondents were from the South (n = 130, 39%) and Midwest (n = 123, 37%) regions, and over half (n = 179, 54%) were female. Most respondents (n = 285, 86%) stated that they did not have children. The majority (n = 236, 71%) were completing residency in an area where they had not previously lived for more than 1 year.

Primary Care Utilization

Among the 348 respondents, 59% (n = 205) reported having established care with a PCP. An additional 6% (n = 21) had established care with an obstetrician/gynecologist for routine needs (Table 2). The 2 most common reasons for establishing care with a PCP were routine primary care needs, including contraception (n = 159, 79%), and access to a physician in the event of an acute medical need (n = 132, 66%).

Among respondents who had established care with a PCP, most (n = 188, 94%) had completed at least 1 appointment. However, among these 188 respondents, 68% (n = 127) stated that they had not made an acute visit in more than 12 months. When asked about wellness visits, almost one third of respondents (n = 103, 31%) stated that they had not been seen for a wellness visit in the past 3 years.

Burden of Chronic Illness

Most respondents (n = 223, 67%) stated that they did not have a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency (Table 3). However, 23% (n = 77) of respondents stated that they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness prior to residency, and 14% (n = 45) indicated they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition prior to residency. Almost one fifth of respondents (n = 60, 18%) reported seeing a subspecialist for a medical illness, and 33% (n = 111) reported taking a long-term prescription medication. With respect to major medical issues, the majority of residents (n = 239, 72%) denied experiencing events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, or an emergency department (ED) visit during training.

[polldaddy:10116940]

Inappropriate Prescriptions

While the majority of respondents denied writing a prescription for themselves for an acute or chronic medical condition, almost one fifth (n = 62, 19%) had received a prescription for an acute medical need from a provider outside of a clinical relationship (ie, from someone other than their PCP or specialty provider). Notably, 5% (n = 15) reported that this had occurred at least 2 or 3 times in the past 12 months (Table 4). Compared to respondents not taking long-term prescription medications, respondents who were already taking long-term prescription medications more frequently reported inappropriately receiving chronic prescriptions outside of an established clinical relationship (n = 14, 13% vs. n = 14, 6%; P = 0.05) and more often self-prescribed medications for acute needs (n = 12, 11% vs. n = 7, 3%; P = 0.005).

Comparison of Residents With and Without a PCP

Important differences were noted between residents who had a PCP versus those who did not (Table 5). For example, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP indicated they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness (n = 55, 28% vs. n = 22, 16%; P = 0.01) or a chronic mental health condition (n = 34, 17% vs. n = 11, 8%; P = 0.02) before residency. Additionally, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP (n = 70, 35% vs. n = 25, 18%; P = 0.001) reported experiencing medical events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, ED visit, or new diagnosis of a chronic medical illness during residency. Finally, a higher percentage of respondents with a PCP stated that they had visited a subspecialist for a medical illness (n = 44, 22% vs. n = 16,12%; P = 0.01) or were taking long-term prescription medications (n = 86, 43% vs. n = 25; 18%; P < 0.001). When comparing PGY-1 to PGY-2–PGY-4 residents, the former reported having established a medical relationship with a PCP significantly less frequently (n = 56, 43% vs. n = 142, 70%; P < 0.001).

Discussion

This survey-based study of medical residents across the United States suggests that a substantial proportion do not establish relationships with PCPs. Additionally, our data suggest that despite establishing care, few residents subsequently visited their PCP during training for wellness visits or routine care. Self-reported rates of chronic medical and mental health conditions were substantial in our sample. Furthermore, inappropriate self-prescription and the receipt of prescriptions outside of a medical relationship were also reported. These findings suggest that future studies that focus on the unique medical and mental health needs of physicians in training, as well as interventions to encourage care in this vulnerable period, are necessary.

We observed that most respondents that established primary care were female trainees. Although it is impossible to know with certainty, one hypothesis behind this discrepancy is that women routinely need to access preventative care for gynecologic needs such as pap smears, contraception, and potentially pregnancy and preconception counseling [14,15]. Similarly, residents with a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency established care with a local PCP at a significantly greater frequency than those without such diagnoses. While selection bias cannot be excluded, this finding suggests that illness is a driving factor in establishing care. There also appears to be an association between accessing the medical system (either for prescription medications or subspecialist care) and having established care with a PCP. Collectively, these data suggest that individuals without a compelling reason to access medical services might have barriers to accessing care in the event of medical needs or may not receive routine preventative care [9,10].

In general, we found that rates of reported inappropriate prescriptions were lower than those reported in prior studies where a comparable resident population was surveyed [8,12,16]. Inclusion of multiple institutions, differences in temporality, social desirability bias, and reporting bias might have influenced our findings in this regard. Surprisingly, we found that having a PCP did not influence likelihood of inappropriate prescription receipt, perhaps suggesting that this behavior reflects some degree of universal difficulty in accessing care. Alternatively, this finding might relate to a cultural tendency to self-prescribe among resident physicians. The fact that individuals on chronic medications more often both received and wrote inappropriate prescriptions suggests this problem might be more pronounced in individuals who take medications more often, as these residents have specific needs [12]. Future studies targeting these individuals thus appear warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample size was modest and the response rate of 45% was low. However, to our knowledge, this remains among the largest survey on this topic, and our response rate is comparable to similar trainee studies [8,11,13]. Second, we designed and created a novel survey for this study. While the questions were pilot-tested with users prior to dissemination, validation of the instrument was not performed. Third, since the study population was restricted to residents in fields that participate in primary care, our findings may not be generalizable to patterns of PCP use in other specialties [6].

These limitations aside, our study has important strengths. This is the first national study of its kind with specific questions addressing primary care access and utilization, prescription medication use and related practices, and the prevalence of medical conditions among trainees. Important differences in the rates of establishing primary care between male and female respondents, first- year and senior residents, and those with and without chronic disease suggest a need to target specific resident groups (males, interns, those without pre-existing conditions) for wellness-related interventions. Such interventions could include distribution of a list of local providers to first year residents, advanced protected time for doctor’s appointments, and safeguards to ensure health information is protected from potential supervisors. Future studies should also include residents from non-primary care oriented specialties such as surgery, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology to obtain results that are more generalizable to the resident population as a whole. Additionally, the rates of inappropriate prescriptions were not insignificant and warrant further evaluation of the driving forces behind these behaviors.

Conclusion

Medical residents have a substantial burden of chronic illness that may not be met through interactions with PCPs. More research into barriers that residents face while accessing care and an assessment of interventions to facilitate their access to care is important to promote trainee well-being. Without such direction and initiative, it may prove harder for physicians to heal themselves or those for whom they provide care.

Acknowledgments: We thank Suzanne Winter, the study coordinator, for her support with editing and formatting the manuscript, Latoya Kuhn for performing the statistical analysis and creating data tables, and Dr. Namita Sachdev and Dr. Renuka Tipirneni for providing feedback on the survey instrument. We also thank the involved programs for their participation.

Corresponding author: Vineet Chopra, NCRC 2800 Plymouth Rd., Bldg 16, 432, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, vineetc@med.umich.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Previous presentations: Results were presented at the Annual Michigan Medicine 2017 Internal Medicine Research Symposium.

From the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Existing research has demonstrated overall low rates of residents establishing care with a primary care physician (PCP). We conducted a survey-based study to better understand chronic illness, PCP utilization, and prescription medication use patterns in resident physician populations.

- Methods: In 2017, we invited internal and family medicine trainees from a convenience sample of U.S. residency programs to participate in a survey. We compared the characteristics of residents who had established care with a PCP to those who had not.

- Results: The response rate was 45% (348/766 residents). The majority (n = 205, 59%) of respondents stated they had established care with a PCP primarily for routine preventative care (n = 159, 79%) and access in the event of an emergency (n = 132, 66%). However, 31% (n = 103) denied having had a wellness visit in over 3 years. Nearly a quarter of residents (n = 77, 23%) reported a chronic medical illness and 14% (n = 45) reported a preexisting mental health condition prior to residency. One-third (n = 111, 33%) reported taking a long-term prescription medication. Compared to residents who had not established care, those with a PCP (n = 205) more often reported a chronic condition (P < 0.001), seeing a subspecialist (P = 0.01), or taking long-term prescription medications (P < 0.001). One in 5 (n = 62,19%) respondents reported receiving prescriptions for an acute illness from an individual with whom they did not have a doctor-patient relationship.

- Conclusion: Medical residents have a substantial burden of chronic illness that may not be met through interactions with PCPs. Further understanding their medical needs and barriers to accessing care is necessary to ensure trainee well-being.

Keywords: Medical education-graduate, physician behavior, survey research, access to care.

Although internal medicine (IM) and family medicine (FM) residents must learn to provide high-quality primary care to their patients, little is known about whether they appropriately access such care themselves. Resident burnout and resilience has received attention [1,2], but there has been limited focus on understanding the burden of chronic medical and mental illness among residents. In particular, little is known about whether residents access primary care physicians (PCPs)—for either acute or chronic medical needs—and about resident self-medication practices.

Residency is often characterized by a life-changing geographic relocation. Even residents who do not relocate may still need to establish care with a new PCP due to health insurance or loss of access to a student clinic [3]. Establishing primary care with a new doctor typically requires scheduling a new patient visit, often with a wait time of several days to weeks [4,5]. Furthermore, lack of time, erratic schedules, and concerns about privacy and the stigma of being ill as a physician are barriers to establishing care [6-8]. Individuals who have not established primary care may experience delays in routine preventative health services, screening for chronic medical and mental health conditions, as well as access to care during acute illnesses [9,10]. Worse, they may engage in potentially unsafe practices, such as having colleagues write prescriptions for them, or even self-prescribing [8,11,12].

Existing research has demonstrated overall low rates of residents establishing care with a PCP [6–8,13]. However, these studies have either been limited to large academic centers or conducted outside the United States. Improving resident well-being may prove challenging without a clear understanding of current primary care utilization practices, the burden of chronic illness among residents, and patterns of prescription medication use and needs. Therefore, we conducted a survey-based study to understand primary care utilization and the burden of chronic illness among residents. We also assessed whether lack of primary care is associated with potentially risky behaviors, such as self-prescribing of medications.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

The survey was distributed to current residents at IM and FM programs within the United States in 2017. Individual programs were recruited by directly contacting program directors or chief medical residents via email. Rather than contacting sites directly through standard templated emails, we identified programs both through personal contacts as well as the Electronic Residency Application Service list of accredited IM training programs. We elected to use this approach in order to increase response rates and to ensure that a sample representative of the trainee population was constructed. Programs were located in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and Pacific regions, and included small community-based programs and large academic centers.

Development of the Survey

The survey instrument was developed by the authors and reviewed by residents and PCPs at the University of Michigan to ensure relevance and comprehension of questions (The survey is available in the Appendix.). Once finalized, the survey was programmed into an online survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and pilot-tested before being disseminated to the sampling frame. Data collected in the survey included: respondent’s utilization of a PCP, burden of chronic illness, long-term prescription medications, prescribing source, and demographic characteristics.

Each participating program distributed the survey to their residents through an email containing an anonymous hyperlink. The survey was available for completion for 4 weeks. We asked participating programs to send email reminders to encourage participation. Participants were given the option of receiving a $10 Amazon gift card after completion. All responses were recorded anonymously. The study received a “not regulated” status by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM 00123888).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate results. Respondents were encouraged, but not required, to answer all questions. Therefore, the response rate for each question was calculated using the total number of responses for that question as the denominator. Bivariable comparisons were made using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical data. A P value < 0.05, with 2-sided alpha, was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

Of the 29 programs contacted, 10 agreed to participate within the study timeframe. Of 766 potential respondents, 348 (45%) residents answered the survey (Table 1). The majority of respondents (n = 276, 82%) were from IM programs. Respondents were from all training years as follows: postgraduate year 1 residents (PGY-1, or interns; n = 130, 39%), PGY-2 residents (n = 98, 29%), PGY-3 residents (n = 93, 28%), and PGY-4 residents (n = 12, 4%). Most respondents were from the South (n = 130, 39%) and Midwest (n = 123, 37%) regions, and over half (n = 179, 54%) were female. Most respondents (n = 285, 86%) stated that they did not have children. The majority (n = 236, 71%) were completing residency in an area where they had not previously lived for more than 1 year.

Primary Care Utilization

Among the 348 respondents, 59% (n = 205) reported having established care with a PCP. An additional 6% (n = 21) had established care with an obstetrician/gynecologist for routine needs (Table 2). The 2 most common reasons for establishing care with a PCP were routine primary care needs, including contraception (n = 159, 79%), and access to a physician in the event of an acute medical need (n = 132, 66%).

Among respondents who had established care with a PCP, most (n = 188, 94%) had completed at least 1 appointment. However, among these 188 respondents, 68% (n = 127) stated that they had not made an acute visit in more than 12 months. When asked about wellness visits, almost one third of respondents (n = 103, 31%) stated that they had not been seen for a wellness visit in the past 3 years.

Burden of Chronic Illness

Most respondents (n = 223, 67%) stated that they did not have a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency (Table 3). However, 23% (n = 77) of respondents stated that they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness prior to residency, and 14% (n = 45) indicated they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition prior to residency. Almost one fifth of respondents (n = 60, 18%) reported seeing a subspecialist for a medical illness, and 33% (n = 111) reported taking a long-term prescription medication. With respect to major medical issues, the majority of residents (n = 239, 72%) denied experiencing events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, or an emergency department (ED) visit during training.

[polldaddy:10116940]

Inappropriate Prescriptions

While the majority of respondents denied writing a prescription for themselves for an acute or chronic medical condition, almost one fifth (n = 62, 19%) had received a prescription for an acute medical need from a provider outside of a clinical relationship (ie, from someone other than their PCP or specialty provider). Notably, 5% (n = 15) reported that this had occurred at least 2 or 3 times in the past 12 months (Table 4). Compared to respondents not taking long-term prescription medications, respondents who were already taking long-term prescription medications more frequently reported inappropriately receiving chronic prescriptions outside of an established clinical relationship (n = 14, 13% vs. n = 14, 6%; P = 0.05) and more often self-prescribed medications for acute needs (n = 12, 11% vs. n = 7, 3%; P = 0.005).

Comparison of Residents With and Without a PCP

Important differences were noted between residents who had a PCP versus those who did not (Table 5). For example, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP indicated they had been diagnosed with a chronic medical illness (n = 55, 28% vs. n = 22, 16%; P = 0.01) or a chronic mental health condition (n = 34, 17% vs. n = 11, 8%; P = 0.02) before residency. Additionally, a higher percentage of residents with a PCP (n = 70, 35% vs. n = 25, 18%; P = 0.001) reported experiencing medical events such as pregnancy, hospitalization, surgery, ED visit, or new diagnosis of a chronic medical illness during residency. Finally, a higher percentage of respondents with a PCP stated that they had visited a subspecialist for a medical illness (n = 44, 22% vs. n = 16,12%; P = 0.01) or were taking long-term prescription medications (n = 86, 43% vs. n = 25; 18%; P < 0.001). When comparing PGY-1 to PGY-2–PGY-4 residents, the former reported having established a medical relationship with a PCP significantly less frequently (n = 56, 43% vs. n = 142, 70%; P < 0.001).

Discussion

This survey-based study of medical residents across the United States suggests that a substantial proportion do not establish relationships with PCPs. Additionally, our data suggest that despite establishing care, few residents subsequently visited their PCP during training for wellness visits or routine care. Self-reported rates of chronic medical and mental health conditions were substantial in our sample. Furthermore, inappropriate self-prescription and the receipt of prescriptions outside of a medical relationship were also reported. These findings suggest that future studies that focus on the unique medical and mental health needs of physicians in training, as well as interventions to encourage care in this vulnerable period, are necessary.

We observed that most respondents that established primary care were female trainees. Although it is impossible to know with certainty, one hypothesis behind this discrepancy is that women routinely need to access preventative care for gynecologic needs such as pap smears, contraception, and potentially pregnancy and preconception counseling [14,15]. Similarly, residents with a chronic medical or mental health condition prior to residency established care with a local PCP at a significantly greater frequency than those without such diagnoses. While selection bias cannot be excluded, this finding suggests that illness is a driving factor in establishing care. There also appears to be an association between accessing the medical system (either for prescription medications or subspecialist care) and having established care with a PCP. Collectively, these data suggest that individuals without a compelling reason to access medical services might have barriers to accessing care in the event of medical needs or may not receive routine preventative care [9,10].

In general, we found that rates of reported inappropriate prescriptions were lower than those reported in prior studies where a comparable resident population was surveyed [8,12,16]. Inclusion of multiple institutions, differences in temporality, social desirability bias, and reporting bias might have influenced our findings in this regard. Surprisingly, we found that having a PCP did not influence likelihood of inappropriate prescription receipt, perhaps suggesting that this behavior reflects some degree of universal difficulty in accessing care. Alternatively, this finding might relate to a cultural tendency to self-prescribe among resident physicians. The fact that individuals on chronic medications more often both received and wrote inappropriate prescriptions suggests this problem might be more pronounced in individuals who take medications more often, as these residents have specific needs [12]. Future studies targeting these individuals thus appear warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample size was modest and the response rate of 45% was low. However, to our knowledge, this remains among the largest survey on this topic, and our response rate is comparable to similar trainee studies [8,11,13]. Second, we designed and created a novel survey for this study. While the questions were pilot-tested with users prior to dissemination, validation of the instrument was not performed. Third, since the study population was restricted to residents in fields that participate in primary care, our findings may not be generalizable to patterns of PCP use in other specialties [6].

These limitations aside, our study has important strengths. This is the first national study of its kind with specific questions addressing primary care access and utilization, prescription medication use and related practices, and the prevalence of medical conditions among trainees. Important differences in the rates of establishing primary care between male and female respondents, first- year and senior residents, and those with and without chronic disease suggest a need to target specific resident groups (males, interns, those without pre-existing conditions) for wellness-related interventions. Such interventions could include distribution of a list of local providers to first year residents, advanced protected time for doctor’s appointments, and safeguards to ensure health information is protected from potential supervisors. Future studies should also include residents from non-primary care oriented specialties such as surgery, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology to obtain results that are more generalizable to the resident population as a whole. Additionally, the rates of inappropriate prescriptions were not insignificant and warrant further evaluation of the driving forces behind these behaviors.

Conclusion

Medical residents have a substantial burden of chronic illness that may not be met through interactions with PCPs. More research into barriers that residents face while accessing care and an assessment of interventions to facilitate their access to care is important to promote trainee well-being. Without such direction and initiative, it may prove harder for physicians to heal themselves or those for whom they provide care.

Acknowledgments: We thank Suzanne Winter, the study coordinator, for her support with editing and formatting the manuscript, Latoya Kuhn for performing the statistical analysis and creating data tables, and Dr. Namita Sachdev and Dr. Renuka Tipirneni for providing feedback on the survey instrument. We also thank the involved programs for their participation.

Corresponding author: Vineet Chopra, NCRC 2800 Plymouth Rd., Bldg 16, 432, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, vineetc@med.umich.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Previous presentations: Results were presented at the Annual Michigan Medicine 2017 Internal Medicine Research Symposium.

1. Kassam A, Horton J, Shoimer I, Patten S. Predictors of well-being in resident physicians: a descriptive and psychometric study. J Grad Med Educ 2015;7:70–4.

2. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:358–67.

3. Burstin HR, Swartz K, O’Neil AC, et al. The effect of change of health insurance on access to care. Inquiry 1998;35:389–97.

4. Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Friedman AB, et al. Access to primary care appointments following 2014 insurance expansions. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:107–12.

5. Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, et al. Appointment availability after increases in Medicaid payments for primary care. N Engl J Med 2015;372:537–45.

6. Gupta G, Schleinitz MD, Reinert SE, McGarry KA. Resident physician preventive health behaviors and perspectives on primary care. R I Med J (2013) 2013;96:43–7.

7. Rosen IM, Christine JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:116-21.

8. Campbell S, Delva D. Physician do not heal thyself. Survey of personal health practices among medical residents. Can Fam Physician 2003;49:1121–7.

9. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502.

10. Weissman JS, Stern R, Fielding SL, et al. Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:325–31.

11. Guille C, Sen S. Prescription drug use and self-prescription among training physicians. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:371–2.

12. Roberts LW, Kim JP. Informal health care practices of residents: “curbside” consultation and self-diagnosis and treatment. Acad Psychiatry 2015;39:22-30.

13. Cohen JS, Patten S. Well-being in residency training: a survey examining resident physician satisfaction both within and outside of residency training and mental health in Alberta. BMC Med Educ 2005;5:21.

14. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Published March 2012. Accessed August 21, 2018.

15. Health Resources and Services Administration. Women’s preventative services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines2016/index.html. Updated October 2017. Accessed August 21, 2018.

16. Christie JD, Rosen IM, Bellini LM, et al. Prescription drug use and self-prescription among resident physicians. JAMA 1998;280(14):1253–5.

1. Kassam A, Horton J, Shoimer I, Patten S. Predictors of well-being in resident physicians: a descriptive and psychometric study. J Grad Med Educ 2015;7:70–4.

2. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:358–67.

3. Burstin HR, Swartz K, O’Neil AC, et al. The effect of change of health insurance on access to care. Inquiry 1998;35:389–97.

4. Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Friedman AB, et al. Access to primary care appointments following 2014 insurance expansions. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:107–12.

5. Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, et al. Appointment availability after increases in Medicaid payments for primary care. N Engl J Med 2015;372:537–45.

6. Gupta G, Schleinitz MD, Reinert SE, McGarry KA. Resident physician preventive health behaviors and perspectives on primary care. R I Med J (2013) 2013;96:43–7.

7. Rosen IM, Christine JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:116-21.

8. Campbell S, Delva D. Physician do not heal thyself. Survey of personal health practices among medical residents. Can Fam Physician 2003;49:1121–7.

9. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502.

10. Weissman JS, Stern R, Fielding SL, et al. Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:325–31.

11. Guille C, Sen S. Prescription drug use and self-prescription among training physicians. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:371–2.

12. Roberts LW, Kim JP. Informal health care practices of residents: “curbside” consultation and self-diagnosis and treatment. Acad Psychiatry 2015;39:22-30.

13. Cohen JS, Patten S. Well-being in residency training: a survey examining resident physician satisfaction both within and outside of residency training and mental health in Alberta. BMC Med Educ 2005;5:21.

14. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical cancer: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Published March 2012. Accessed August 21, 2018.

15. Health Resources and Services Administration. Women’s preventative services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines2016/index.html. Updated October 2017. Accessed August 21, 2018.

16. Christie JD, Rosen IM, Bellini LM, et al. Prescription drug use and self-prescription among resident physicians. JAMA 1998;280(14):1253–5.