User login

In hospitals, clinicians constantly encounter conflicting and ambiguous information,” says Ronald M. Epstein, MD, professor of family medicine, psychiatry, and oncology at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) N.Y. “This information often gets processed tacitly, outside of awareness, and often results in various undesired consequences. For example, premature closure of diagnostic thinking or ordering a test rather than inquiring further of the patient.” In the average hospital, distractions and sensory inputs, including smells, sights, sounds, and tactile sensations, as well as multiple tasks to complete, can all seem pretty overwhelming. Faced with so much data, says Dr. Epstein, the tendency of the mind is to simplify and reduce it in some way. And that’s when error can rear its ugly head.

“Simplification is often arbitrary and unconscious,” he says, and thus “the trick of working in hospital is to develop a vigilant awareness of the ambient stimuli that are all around you, making choices as to what you attend to, relegating other stimuli to the background, and in that way avoiding becoming overwhelmed or controlled by them. In that way, you have the capacity for making better judgments.”

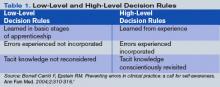

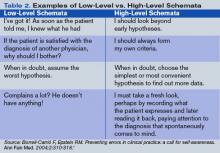

Some clinical decisions can be made fairly easily and routinely (low-level decisions), he says, whereas other patient situations require a fair bit of deliberation (high-level decisions). (See Tables 1 and 2, right.) The human mind tends to avoid the unpleasant and to give more attention to what is compelling. Also, the ambiguity of role and responsibility—especially in large hospitals—may further confound a hospitalist’s mental capacity. Keen attention to each moment also boosts physician well being.

“Hospitalists are often working in crowded, stressful, high-paced, windowless environments in which there is no natural form of respite,” says Dr. Epstein. Therefore, all physicians need ways of keeping themselves from being overwhelmed by the challenges of sensory input and intense emotions caused by exposure to suffering, conflicts, imperatives for critical thinking, and so on.

“If practitioners were able to be more mindful,” he says, “they might experience greater well-being, because they would be able to make more choices about what they attend to and how they react to them.”

Dr. Epstein and his colleagues at the University of Rochester Medical Center—Timothy Quill, MD, Michael Krasner, MD, and Howard Beckman, MD—have studied the qualities of mind required to exercise that awareness extensively, especially as they relate to clinical practice and education.2 They were recently awarded three complementary grants to teach mindfulness to physicians: one from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, another from the Physicians’ Foundation for Health Systems Excellence, and the Mannix Award for Excellence in Medical Education.

But just what does mindfulness in medicine entail?

Defining Mindful Practice

“Mindful practice is recognizing where you are at every moment. If you’re distressed, if you’re content or unhappy, if you’re comfortable or in pain, if you’re experiencing some kind of positive or negative effect, if you’re feeling in tune or disconnected from yourself. It’s that monitoring function to be able to say, I’m angry or I’m uncomfortable, or, possibly, I’m in the flow,” says Dr. Epstein.

For physicians to be able to exercise those qualities of mind, to watch and deconstruct their own behavior (what Dr. Epstein describes as “the ability to observe the observer observing the observed”) is something that goes back a long way for him.3 “There’s nothing really mystical about it,” he says. “People do this all the time. It’s part of being an excellent professional in lots of fields. It’s just that no one has organized the science of doing so in the context of medical training.”

In the late 1990s, Dr. Epstein and his coworkers implemented a curriculum reform process at URMC, and his particular charge was to assess the competence of medical students. To accomplish this, he did two things. First, he reviewed the literature on the assessment and definitions of special competence. Second, he turned the magnifying glass on himself. “I thought that it might be a useful exercise to try to understand what made me practice at my best and what barriers there were to doing so.”

The resulting article from this self-monitoring and evaluation was published in JAMA in 1999, before the review article on defining and assessing professional competence appeared in that same journal.3,4 Exploring the nature of his own mindful practice reacquainted him with two areas in which he had participated as a teenager: music and the study of mind—particularly the use of meditation to enhance mental capacities. Those inquiries led him to explore the psychology of a number of qualities of mind: attentiveness, curiosity, decision-making, and the use of cognitive knowledge. The literature was convergent in a number of ways, he says, and “seemed to point to the fact that a lot of competence is not a matter of book knowledge or the kind of knowledge we can explain but tacit knowledge, things we do semi-automatically that really take some effort to deconstruct.”

He realized that “what distinguished an excellent clinician from someone who wasn’t quite so excellent had to do with some of those same qualities that one sees in accomplished musicians, athletes, and meditators, which is the ability to make fine distinctions, lower one’s own level of reactivity, respond in a more conscious way, and pay attention to the unexpected—the surprises that are part of everyday work but that we often ignore.”

All of this rather radicalized his view of what medical education should be doing. He came to believe that—on top of a foundation of knowledge and skills—physicians need to be attentive to their own mental processes and alert to the effects of bias or prior experience.

Writing about excellent clinical practice in this way drew a crescendo of response from readers of the JAMA. The JAMA editors had thoroughly engaged in helping him refine and present the ideas in a way that would really speak to clinical practitioners and educators.3 After publication, he was amazed to receive hundreds of letters from all over the world from physicians in different specialties expressing their appreciation “for having articulated something that was really at the heart of medicine,” he says. “For me, that was incredibly gratifying.”

Hospitalist Qualities of Mind

What qualities of mind are important for a hospitalist to have?

“You have to be enthusiastic, fast-paced individuals,” says Yousaf Ali, MD, hospitalist at URMC and assistant professor of medicine in the Hospital Medicine Division. You also have to be able to immediately connect with patients and families and to have the knowledge and passion that makes that possible. Further, he says, you need to quickly access knowledge pertaining to caring for patients with multiple problems.

Traci Ferguson, MD, is a hospitalist at Boca Raton Community Hospital in Florida, which, by affiliating with Florida Atlantic University (the regional campus for the University of Miami School of Medicine), is moving from community hospital to teaching hospital. Dr. Ferguson believes the qualities of mind necessary to be a good hospitalist are the capacity to be aware of reactions and biases toward patients in order to avoid being judgmental.

“I think the major thing is being present and being attentive when you are caring for patients,” she says, “and that occurs when you’re writing a chart, when you’re talking to family members, [and] when you’re talking to nurses, just as it does when you’re at the bedside.”

Other qualities of mind, in Dr. Ferguson’s view, include the whole spectrum of empathy and compassion, being personable in the sense of being open to what patients and families have to say, and being patient. She also believes the quality of mind necessary to express a human touch is sometimes missing.

Valerie Lang, MD, is also a hospitalist at URMC and has studied mindfulness with Dr. Epstein. She is enrolled in Dr. Krasner’s class for healthcare providers on being mindful. What qualities of mind does she think are important for a hospitalist to have?

“I want to say an open mind, but that’s such a broad term,” she says. “Dr. Epstein uses the term ‘beginner’s mind’ [to refer to] when you’re willing to consider many alternatives, where you don’t necessarily jump to a conclusion and then just stick with it. As a hospitalist, you start making those conclusions as soon as you hear what the patient’s chief complaint is. I think that having [a] beginner’s mind … is so important because we don’t know these patients, and it’s easy to jump to conclusions because we have to make decisions very quickly and … repeatedly.” She also believes that “being able to reflect on how you are communicating with another person is incredibly important to their care.”

—Valerie Lang, MD, hospitalist, University of Rochester Medical Center

Operationalizing Mindfulness

In 2004, after the publication of two of Dr. Epstein’s articles on mindful practice in action, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation approached him and requested a proposal.5,6 At that time, he was in the process of writing an article on reflection and mindfulness in the context of preventing errors.1 (See Table 3, left.)

“This [proposal] was an intriguing possibility,” says Dr. Epstein, “and galvanized my putting together a curriculum that would not just be elective experiences for preclinical students, which is what the offerings related to mindfulness currently are, but something that was really going to influence clinical training.”

In Dr. Epstein’s view, placing educational reform in the first two years of medical school is teaching it when it matters the least. “Where it matters the most is when students are interacting with patients and using the knowledge and skills and doing work that they’ll ultimately end up doing for the next 30 or 40 years,” says Dr. Epstein.

One project plan is to train practicing primary care physicians to communicate more mindfully with their patients. Outcomes of the intervention will be measured by how it has affected the physicians as well as the patients’ ratings of their physicians and their practice styles.

The second project is a series of annual workshops for 100 third-year medical students and about 250 residents in the nine largest programs at the medical center. All participants will take five seminars that include mindfulness techniques to improve the capacity for paying attention and observing, and narrative exercises, whose themes will include, for instance, suffering, meaningful experience, professionalism, physician self-care, and avoiding burnout. The coursework, which will include both cognitive and experiential content, will also involve training a cadre of about 20 faculty members to teach these sessions, and educational outcomes will ultimately be measured for all participants.

Focus on Metacognition

Dr. Epstein, director of The Rochester Center to Improve Communication in Health Care, says metacognition builds on other approaches, such as the Healer’s Art, a course designed by Rachel Remen, MD, and colleagues, which a number of medical centers are incorporating into their curricula.7

“We are building on Dr. Remen’s wonderful work,” he says. Both curricula include self-awareness, humanism, caring, compassion, meaningful experiences, and physician well being. Both address the “informal curriculum”—a term used to refer to the social environment in which medical trainees adopt values, expectations, and clinical habits. In addition, Dr. Epstein and his colleagues focus on quality of clinical care, including medical decision-making and preventing errors.

“Importantly, our initiative is part of the required curriculum,” says Dr. Epstein. “It targets students and residents working in clinical settings at an advanced level, and it also has a faculty component. … We are trying to transform and heal the informal curriculum, not just immunize students against its toxicity.”

In the Thick of It

All this sounds as if it might benefit hospital practice, according to the hospitalists interviewed for this story. All three believe that mindfulness can be cultivated. Dr. Ali believes the aforementioned forces acting on hospitalists require that hospitalists work at their top capacities, but prioritizing remains essential. He believes one way a hospitalist can cultivate mindfulness in the patient-physician relationship is to avoid burnout in any way that works. Having been a hospitalist for almost 10 years, he discusses this with his medical students and residents. In addition to his hospitalist practice and teaching, Dr. Ali does patient-related quality work, which refreshes his energy.

Dr. Ferguson also thinks mindful practice can be cultivated. “I took cues from the nursing profession in realizing that you do have to care for all aspects of the patient,” she says. “But you can learn this from mentors and people who are successful: people you can emulate, shadow, and follow.”

For her, such a person is Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Dr. Cooper, both a practicing internist and a researcher, studies and teaches about communication between physicians and minorities—that is, how physicians interact with people of the same or different races and ethnicities. Dr. Ferguson says she feels fortunate to have adopted a mindful awareness in that regard.

As director of the medicine clerkship, Dr. Lang came into contact with Dr. Epstein’s project through her Dean’s Teaching Fellowship, a competitive program at the URSM for faculty members who have a special interest in education.

“The discussions with other educators and clinicians really got me thinking about how my own feelings, whether they had to do with a patient or anything else in life, affect my decision-making,” says Dr. Lang. “You see the phenomenon in residency where you’re in morning report when the residents present a patient and everyone is sitting around a table—not involved with the patient—making judgments about what they should have done. It’s so much easier when you’re not involved [in the situation].”

Though Dr. Lang thinks there are a lot of reasons for that, “part of it is that you are not in the excitement of the moment. And the other factor is that when you’re presenting a patient to a group, you wouldn’t convey your own emotions, what else was going on, what were the competing pressures. Even if you have a wonderful intellect and clinical reasoning skills, you might make the wrong decision when you’re in the thick of the situation.”

Mindful Hospital Practice

Dr. Lang has seen a number of outcomes from her study of mindful practice. It has made her aware of her biases and has taught her to say, in certain cases, “OK, I need to think through the problem again to make sure I’m not changing my judgment about what we should be doing clinically based on how I’m feeling about a patient.”

Dr. Lang sometimes asks herself, “How am I feeling about this? Did that wear me down?” Or, sometimes the opposite can occur. A patient can make you feel “puffed up, where they are so complimentary and make you feel so good that you think that every decision you make is perfect,” she explains.

What Dr. Lang has learned about herself has helped her recognize when she might have prematurely closed a differential diagnosis or come to a conclusion too quickly simply because the patient appeared to agree with her clinical assessment.

Dr. Lang also thinks being a mindful physician has made her a better physician and that she is providing better care that results in better outcomes. “I definitely communicate better with my patients. … I think my relationships with my patients have significantly improved.”

What is her recommendation for how her hospitalist colleagues can learn to practice mindfully? “It’s a practice, and it’s a matter of practice,” says Dr. Lang. “It’s not something you get overnight. It’s a matter of every day, every encounter, taking the time before entering the patient’s room to pause, put things aside, and be present with the patient. And then, at the end of the day, take some time to reflect.”

How does education for mindfulness differ from her original medical training? “I don’t think you’re really ever taught how to manage your emotions when you’ve just made a medical error and you are distraught,” says Dr. Lang, “or how to manage doing that when your pager is going off like crazy and yet you need to sit down and be present with your patient. And that’s the kind of thing that ends up being in your way of being the best physician you can be.” TH

References

- Borrell-Carrió F, Epstein RM. Preventing errors in clinical practice: a call for self-awareness. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:310-316.

- Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):387-396.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999 Sep;282(9):833-839.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002 Jan 9;287(2):226-235.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (I): technical competence, evidence-based medicine and relationship-centered care. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21:1-9.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (II): cultivating habits of mind. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21:11-17.

- O’Donnell JF, Rabow MW, Remen RN. The healer’s art: awakening the heart of medicine. Medical Encounter: Newsletter of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. 2007;21, No 1.

In hospitals, clinicians constantly encounter conflicting and ambiguous information,” says Ronald M. Epstein, MD, professor of family medicine, psychiatry, and oncology at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) N.Y. “This information often gets processed tacitly, outside of awareness, and often results in various undesired consequences. For example, premature closure of diagnostic thinking or ordering a test rather than inquiring further of the patient.” In the average hospital, distractions and sensory inputs, including smells, sights, sounds, and tactile sensations, as well as multiple tasks to complete, can all seem pretty overwhelming. Faced with so much data, says Dr. Epstein, the tendency of the mind is to simplify and reduce it in some way. And that’s when error can rear its ugly head.

“Simplification is often arbitrary and unconscious,” he says, and thus “the trick of working in hospital is to develop a vigilant awareness of the ambient stimuli that are all around you, making choices as to what you attend to, relegating other stimuli to the background, and in that way avoiding becoming overwhelmed or controlled by them. In that way, you have the capacity for making better judgments.”

Some clinical decisions can be made fairly easily and routinely (low-level decisions), he says, whereas other patient situations require a fair bit of deliberation (high-level decisions). (See Tables 1 and 2, right.) The human mind tends to avoid the unpleasant and to give more attention to what is compelling. Also, the ambiguity of role and responsibility—especially in large hospitals—may further confound a hospitalist’s mental capacity. Keen attention to each moment also boosts physician well being.

“Hospitalists are often working in crowded, stressful, high-paced, windowless environments in which there is no natural form of respite,” says Dr. Epstein. Therefore, all physicians need ways of keeping themselves from being overwhelmed by the challenges of sensory input and intense emotions caused by exposure to suffering, conflicts, imperatives for critical thinking, and so on.

“If practitioners were able to be more mindful,” he says, “they might experience greater well-being, because they would be able to make more choices about what they attend to and how they react to them.”

Dr. Epstein and his colleagues at the University of Rochester Medical Center—Timothy Quill, MD, Michael Krasner, MD, and Howard Beckman, MD—have studied the qualities of mind required to exercise that awareness extensively, especially as they relate to clinical practice and education.2 They were recently awarded three complementary grants to teach mindfulness to physicians: one from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, another from the Physicians’ Foundation for Health Systems Excellence, and the Mannix Award for Excellence in Medical Education.

But just what does mindfulness in medicine entail?

Defining Mindful Practice

“Mindful practice is recognizing where you are at every moment. If you’re distressed, if you’re content or unhappy, if you’re comfortable or in pain, if you’re experiencing some kind of positive or negative effect, if you’re feeling in tune or disconnected from yourself. It’s that monitoring function to be able to say, I’m angry or I’m uncomfortable, or, possibly, I’m in the flow,” says Dr. Epstein.

For physicians to be able to exercise those qualities of mind, to watch and deconstruct their own behavior (what Dr. Epstein describes as “the ability to observe the observer observing the observed”) is something that goes back a long way for him.3 “There’s nothing really mystical about it,” he says. “People do this all the time. It’s part of being an excellent professional in lots of fields. It’s just that no one has organized the science of doing so in the context of medical training.”

In the late 1990s, Dr. Epstein and his coworkers implemented a curriculum reform process at URMC, and his particular charge was to assess the competence of medical students. To accomplish this, he did two things. First, he reviewed the literature on the assessment and definitions of special competence. Second, he turned the magnifying glass on himself. “I thought that it might be a useful exercise to try to understand what made me practice at my best and what barriers there were to doing so.”

The resulting article from this self-monitoring and evaluation was published in JAMA in 1999, before the review article on defining and assessing professional competence appeared in that same journal.3,4 Exploring the nature of his own mindful practice reacquainted him with two areas in which he had participated as a teenager: music and the study of mind—particularly the use of meditation to enhance mental capacities. Those inquiries led him to explore the psychology of a number of qualities of mind: attentiveness, curiosity, decision-making, and the use of cognitive knowledge. The literature was convergent in a number of ways, he says, and “seemed to point to the fact that a lot of competence is not a matter of book knowledge or the kind of knowledge we can explain but tacit knowledge, things we do semi-automatically that really take some effort to deconstruct.”

He realized that “what distinguished an excellent clinician from someone who wasn’t quite so excellent had to do with some of those same qualities that one sees in accomplished musicians, athletes, and meditators, which is the ability to make fine distinctions, lower one’s own level of reactivity, respond in a more conscious way, and pay attention to the unexpected—the surprises that are part of everyday work but that we often ignore.”

All of this rather radicalized his view of what medical education should be doing. He came to believe that—on top of a foundation of knowledge and skills—physicians need to be attentive to their own mental processes and alert to the effects of bias or prior experience.

Writing about excellent clinical practice in this way drew a crescendo of response from readers of the JAMA. The JAMA editors had thoroughly engaged in helping him refine and present the ideas in a way that would really speak to clinical practitioners and educators.3 After publication, he was amazed to receive hundreds of letters from all over the world from physicians in different specialties expressing their appreciation “for having articulated something that was really at the heart of medicine,” he says. “For me, that was incredibly gratifying.”

Hospitalist Qualities of Mind

What qualities of mind are important for a hospitalist to have?

“You have to be enthusiastic, fast-paced individuals,” says Yousaf Ali, MD, hospitalist at URMC and assistant professor of medicine in the Hospital Medicine Division. You also have to be able to immediately connect with patients and families and to have the knowledge and passion that makes that possible. Further, he says, you need to quickly access knowledge pertaining to caring for patients with multiple problems.

Traci Ferguson, MD, is a hospitalist at Boca Raton Community Hospital in Florida, which, by affiliating with Florida Atlantic University (the regional campus for the University of Miami School of Medicine), is moving from community hospital to teaching hospital. Dr. Ferguson believes the qualities of mind necessary to be a good hospitalist are the capacity to be aware of reactions and biases toward patients in order to avoid being judgmental.

“I think the major thing is being present and being attentive when you are caring for patients,” she says, “and that occurs when you’re writing a chart, when you’re talking to family members, [and] when you’re talking to nurses, just as it does when you’re at the bedside.”

Other qualities of mind, in Dr. Ferguson’s view, include the whole spectrum of empathy and compassion, being personable in the sense of being open to what patients and families have to say, and being patient. She also believes the quality of mind necessary to express a human touch is sometimes missing.

Valerie Lang, MD, is also a hospitalist at URMC and has studied mindfulness with Dr. Epstein. She is enrolled in Dr. Krasner’s class for healthcare providers on being mindful. What qualities of mind does she think are important for a hospitalist to have?

“I want to say an open mind, but that’s such a broad term,” she says. “Dr. Epstein uses the term ‘beginner’s mind’ [to refer to] when you’re willing to consider many alternatives, where you don’t necessarily jump to a conclusion and then just stick with it. As a hospitalist, you start making those conclusions as soon as you hear what the patient’s chief complaint is. I think that having [a] beginner’s mind … is so important because we don’t know these patients, and it’s easy to jump to conclusions because we have to make decisions very quickly and … repeatedly.” She also believes that “being able to reflect on how you are communicating with another person is incredibly important to their care.”

—Valerie Lang, MD, hospitalist, University of Rochester Medical Center

Operationalizing Mindfulness

In 2004, after the publication of two of Dr. Epstein’s articles on mindful practice in action, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation approached him and requested a proposal.5,6 At that time, he was in the process of writing an article on reflection and mindfulness in the context of preventing errors.1 (See Table 3, left.)

“This [proposal] was an intriguing possibility,” says Dr. Epstein, “and galvanized my putting together a curriculum that would not just be elective experiences for preclinical students, which is what the offerings related to mindfulness currently are, but something that was really going to influence clinical training.”

In Dr. Epstein’s view, placing educational reform in the first two years of medical school is teaching it when it matters the least. “Where it matters the most is when students are interacting with patients and using the knowledge and skills and doing work that they’ll ultimately end up doing for the next 30 or 40 years,” says Dr. Epstein.

One project plan is to train practicing primary care physicians to communicate more mindfully with their patients. Outcomes of the intervention will be measured by how it has affected the physicians as well as the patients’ ratings of their physicians and their practice styles.

The second project is a series of annual workshops for 100 third-year medical students and about 250 residents in the nine largest programs at the medical center. All participants will take five seminars that include mindfulness techniques to improve the capacity for paying attention and observing, and narrative exercises, whose themes will include, for instance, suffering, meaningful experience, professionalism, physician self-care, and avoiding burnout. The coursework, which will include both cognitive and experiential content, will also involve training a cadre of about 20 faculty members to teach these sessions, and educational outcomes will ultimately be measured for all participants.

Focus on Metacognition

Dr. Epstein, director of The Rochester Center to Improve Communication in Health Care, says metacognition builds on other approaches, such as the Healer’s Art, a course designed by Rachel Remen, MD, and colleagues, which a number of medical centers are incorporating into their curricula.7

“We are building on Dr. Remen’s wonderful work,” he says. Both curricula include self-awareness, humanism, caring, compassion, meaningful experiences, and physician well being. Both address the “informal curriculum”—a term used to refer to the social environment in which medical trainees adopt values, expectations, and clinical habits. In addition, Dr. Epstein and his colleagues focus on quality of clinical care, including medical decision-making and preventing errors.

“Importantly, our initiative is part of the required curriculum,” says Dr. Epstein. “It targets students and residents working in clinical settings at an advanced level, and it also has a faculty component. … We are trying to transform and heal the informal curriculum, not just immunize students against its toxicity.”

In the Thick of It

All this sounds as if it might benefit hospital practice, according to the hospitalists interviewed for this story. All three believe that mindfulness can be cultivated. Dr. Ali believes the aforementioned forces acting on hospitalists require that hospitalists work at their top capacities, but prioritizing remains essential. He believes one way a hospitalist can cultivate mindfulness in the patient-physician relationship is to avoid burnout in any way that works. Having been a hospitalist for almost 10 years, he discusses this with his medical students and residents. In addition to his hospitalist practice and teaching, Dr. Ali does patient-related quality work, which refreshes his energy.

Dr. Ferguson also thinks mindful practice can be cultivated. “I took cues from the nursing profession in realizing that you do have to care for all aspects of the patient,” she says. “But you can learn this from mentors and people who are successful: people you can emulate, shadow, and follow.”

For her, such a person is Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Dr. Cooper, both a practicing internist and a researcher, studies and teaches about communication between physicians and minorities—that is, how physicians interact with people of the same or different races and ethnicities. Dr. Ferguson says she feels fortunate to have adopted a mindful awareness in that regard.

As director of the medicine clerkship, Dr. Lang came into contact with Dr. Epstein’s project through her Dean’s Teaching Fellowship, a competitive program at the URSM for faculty members who have a special interest in education.

“The discussions with other educators and clinicians really got me thinking about how my own feelings, whether they had to do with a patient or anything else in life, affect my decision-making,” says Dr. Lang. “You see the phenomenon in residency where you’re in morning report when the residents present a patient and everyone is sitting around a table—not involved with the patient—making judgments about what they should have done. It’s so much easier when you’re not involved [in the situation].”

Though Dr. Lang thinks there are a lot of reasons for that, “part of it is that you are not in the excitement of the moment. And the other factor is that when you’re presenting a patient to a group, you wouldn’t convey your own emotions, what else was going on, what were the competing pressures. Even if you have a wonderful intellect and clinical reasoning skills, you might make the wrong decision when you’re in the thick of the situation.”

Mindful Hospital Practice

Dr. Lang has seen a number of outcomes from her study of mindful practice. It has made her aware of her biases and has taught her to say, in certain cases, “OK, I need to think through the problem again to make sure I’m not changing my judgment about what we should be doing clinically based on how I’m feeling about a patient.”

Dr. Lang sometimes asks herself, “How am I feeling about this? Did that wear me down?” Or, sometimes the opposite can occur. A patient can make you feel “puffed up, where they are so complimentary and make you feel so good that you think that every decision you make is perfect,” she explains.

What Dr. Lang has learned about herself has helped her recognize when she might have prematurely closed a differential diagnosis or come to a conclusion too quickly simply because the patient appeared to agree with her clinical assessment.

Dr. Lang also thinks being a mindful physician has made her a better physician and that she is providing better care that results in better outcomes. “I definitely communicate better with my patients. … I think my relationships with my patients have significantly improved.”

What is her recommendation for how her hospitalist colleagues can learn to practice mindfully? “It’s a practice, and it’s a matter of practice,” says Dr. Lang. “It’s not something you get overnight. It’s a matter of every day, every encounter, taking the time before entering the patient’s room to pause, put things aside, and be present with the patient. And then, at the end of the day, take some time to reflect.”

How does education for mindfulness differ from her original medical training? “I don’t think you’re really ever taught how to manage your emotions when you’ve just made a medical error and you are distraught,” says Dr. Lang, “or how to manage doing that when your pager is going off like crazy and yet you need to sit down and be present with your patient. And that’s the kind of thing that ends up being in your way of being the best physician you can be.” TH

References

- Borrell-Carrió F, Epstein RM. Preventing errors in clinical practice: a call for self-awareness. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:310-316.

- Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):387-396.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999 Sep;282(9):833-839.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002 Jan 9;287(2):226-235.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (I): technical competence, evidence-based medicine and relationship-centered care. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21:1-9.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (II): cultivating habits of mind. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21:11-17.

- O’Donnell JF, Rabow MW, Remen RN. The healer’s art: awakening the heart of medicine. Medical Encounter: Newsletter of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. 2007;21, No 1.

In hospitals, clinicians constantly encounter conflicting and ambiguous information,” says Ronald M. Epstein, MD, professor of family medicine, psychiatry, and oncology at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) N.Y. “This information often gets processed tacitly, outside of awareness, and often results in various undesired consequences. For example, premature closure of diagnostic thinking or ordering a test rather than inquiring further of the patient.” In the average hospital, distractions and sensory inputs, including smells, sights, sounds, and tactile sensations, as well as multiple tasks to complete, can all seem pretty overwhelming. Faced with so much data, says Dr. Epstein, the tendency of the mind is to simplify and reduce it in some way. And that’s when error can rear its ugly head.

“Simplification is often arbitrary and unconscious,” he says, and thus “the trick of working in hospital is to develop a vigilant awareness of the ambient stimuli that are all around you, making choices as to what you attend to, relegating other stimuli to the background, and in that way avoiding becoming overwhelmed or controlled by them. In that way, you have the capacity for making better judgments.”

Some clinical decisions can be made fairly easily and routinely (low-level decisions), he says, whereas other patient situations require a fair bit of deliberation (high-level decisions). (See Tables 1 and 2, right.) The human mind tends to avoid the unpleasant and to give more attention to what is compelling. Also, the ambiguity of role and responsibility—especially in large hospitals—may further confound a hospitalist’s mental capacity. Keen attention to each moment also boosts physician well being.

“Hospitalists are often working in crowded, stressful, high-paced, windowless environments in which there is no natural form of respite,” says Dr. Epstein. Therefore, all physicians need ways of keeping themselves from being overwhelmed by the challenges of sensory input and intense emotions caused by exposure to suffering, conflicts, imperatives for critical thinking, and so on.

“If practitioners were able to be more mindful,” he says, “they might experience greater well-being, because they would be able to make more choices about what they attend to and how they react to them.”

Dr. Epstein and his colleagues at the University of Rochester Medical Center—Timothy Quill, MD, Michael Krasner, MD, and Howard Beckman, MD—have studied the qualities of mind required to exercise that awareness extensively, especially as they relate to clinical practice and education.2 They were recently awarded three complementary grants to teach mindfulness to physicians: one from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, another from the Physicians’ Foundation for Health Systems Excellence, and the Mannix Award for Excellence in Medical Education.

But just what does mindfulness in medicine entail?

Defining Mindful Practice

“Mindful practice is recognizing where you are at every moment. If you’re distressed, if you’re content or unhappy, if you’re comfortable or in pain, if you’re experiencing some kind of positive or negative effect, if you’re feeling in tune or disconnected from yourself. It’s that monitoring function to be able to say, I’m angry or I’m uncomfortable, or, possibly, I’m in the flow,” says Dr. Epstein.

For physicians to be able to exercise those qualities of mind, to watch and deconstruct their own behavior (what Dr. Epstein describes as “the ability to observe the observer observing the observed”) is something that goes back a long way for him.3 “There’s nothing really mystical about it,” he says. “People do this all the time. It’s part of being an excellent professional in lots of fields. It’s just that no one has organized the science of doing so in the context of medical training.”

In the late 1990s, Dr. Epstein and his coworkers implemented a curriculum reform process at URMC, and his particular charge was to assess the competence of medical students. To accomplish this, he did two things. First, he reviewed the literature on the assessment and definitions of special competence. Second, he turned the magnifying glass on himself. “I thought that it might be a useful exercise to try to understand what made me practice at my best and what barriers there were to doing so.”

The resulting article from this self-monitoring and evaluation was published in JAMA in 1999, before the review article on defining and assessing professional competence appeared in that same journal.3,4 Exploring the nature of his own mindful practice reacquainted him with two areas in which he had participated as a teenager: music and the study of mind—particularly the use of meditation to enhance mental capacities. Those inquiries led him to explore the psychology of a number of qualities of mind: attentiveness, curiosity, decision-making, and the use of cognitive knowledge. The literature was convergent in a number of ways, he says, and “seemed to point to the fact that a lot of competence is not a matter of book knowledge or the kind of knowledge we can explain but tacit knowledge, things we do semi-automatically that really take some effort to deconstruct.”

He realized that “what distinguished an excellent clinician from someone who wasn’t quite so excellent had to do with some of those same qualities that one sees in accomplished musicians, athletes, and meditators, which is the ability to make fine distinctions, lower one’s own level of reactivity, respond in a more conscious way, and pay attention to the unexpected—the surprises that are part of everyday work but that we often ignore.”

All of this rather radicalized his view of what medical education should be doing. He came to believe that—on top of a foundation of knowledge and skills—physicians need to be attentive to their own mental processes and alert to the effects of bias or prior experience.

Writing about excellent clinical practice in this way drew a crescendo of response from readers of the JAMA. The JAMA editors had thoroughly engaged in helping him refine and present the ideas in a way that would really speak to clinical practitioners and educators.3 After publication, he was amazed to receive hundreds of letters from all over the world from physicians in different specialties expressing their appreciation “for having articulated something that was really at the heart of medicine,” he says. “For me, that was incredibly gratifying.”

Hospitalist Qualities of Mind

What qualities of mind are important for a hospitalist to have?

“You have to be enthusiastic, fast-paced individuals,” says Yousaf Ali, MD, hospitalist at URMC and assistant professor of medicine in the Hospital Medicine Division. You also have to be able to immediately connect with patients and families and to have the knowledge and passion that makes that possible. Further, he says, you need to quickly access knowledge pertaining to caring for patients with multiple problems.

Traci Ferguson, MD, is a hospitalist at Boca Raton Community Hospital in Florida, which, by affiliating with Florida Atlantic University (the regional campus for the University of Miami School of Medicine), is moving from community hospital to teaching hospital. Dr. Ferguson believes the qualities of mind necessary to be a good hospitalist are the capacity to be aware of reactions and biases toward patients in order to avoid being judgmental.

“I think the major thing is being present and being attentive when you are caring for patients,” she says, “and that occurs when you’re writing a chart, when you’re talking to family members, [and] when you’re talking to nurses, just as it does when you’re at the bedside.”

Other qualities of mind, in Dr. Ferguson’s view, include the whole spectrum of empathy and compassion, being personable in the sense of being open to what patients and families have to say, and being patient. She also believes the quality of mind necessary to express a human touch is sometimes missing.

Valerie Lang, MD, is also a hospitalist at URMC and has studied mindfulness with Dr. Epstein. She is enrolled in Dr. Krasner’s class for healthcare providers on being mindful. What qualities of mind does she think are important for a hospitalist to have?

“I want to say an open mind, but that’s such a broad term,” she says. “Dr. Epstein uses the term ‘beginner’s mind’ [to refer to] when you’re willing to consider many alternatives, where you don’t necessarily jump to a conclusion and then just stick with it. As a hospitalist, you start making those conclusions as soon as you hear what the patient’s chief complaint is. I think that having [a] beginner’s mind … is so important because we don’t know these patients, and it’s easy to jump to conclusions because we have to make decisions very quickly and … repeatedly.” She also believes that “being able to reflect on how you are communicating with another person is incredibly important to their care.”

—Valerie Lang, MD, hospitalist, University of Rochester Medical Center

Operationalizing Mindfulness

In 2004, after the publication of two of Dr. Epstein’s articles on mindful practice in action, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation approached him and requested a proposal.5,6 At that time, he was in the process of writing an article on reflection and mindfulness in the context of preventing errors.1 (See Table 3, left.)

“This [proposal] was an intriguing possibility,” says Dr. Epstein, “and galvanized my putting together a curriculum that would not just be elective experiences for preclinical students, which is what the offerings related to mindfulness currently are, but something that was really going to influence clinical training.”

In Dr. Epstein’s view, placing educational reform in the first two years of medical school is teaching it when it matters the least. “Where it matters the most is when students are interacting with patients and using the knowledge and skills and doing work that they’ll ultimately end up doing for the next 30 or 40 years,” says Dr. Epstein.

One project plan is to train practicing primary care physicians to communicate more mindfully with their patients. Outcomes of the intervention will be measured by how it has affected the physicians as well as the patients’ ratings of their physicians and their practice styles.

The second project is a series of annual workshops for 100 third-year medical students and about 250 residents in the nine largest programs at the medical center. All participants will take five seminars that include mindfulness techniques to improve the capacity for paying attention and observing, and narrative exercises, whose themes will include, for instance, suffering, meaningful experience, professionalism, physician self-care, and avoiding burnout. The coursework, which will include both cognitive and experiential content, will also involve training a cadre of about 20 faculty members to teach these sessions, and educational outcomes will ultimately be measured for all participants.

Focus on Metacognition

Dr. Epstein, director of The Rochester Center to Improve Communication in Health Care, says metacognition builds on other approaches, such as the Healer’s Art, a course designed by Rachel Remen, MD, and colleagues, which a number of medical centers are incorporating into their curricula.7

“We are building on Dr. Remen’s wonderful work,” he says. Both curricula include self-awareness, humanism, caring, compassion, meaningful experiences, and physician well being. Both address the “informal curriculum”—a term used to refer to the social environment in which medical trainees adopt values, expectations, and clinical habits. In addition, Dr. Epstein and his colleagues focus on quality of clinical care, including medical decision-making and preventing errors.

“Importantly, our initiative is part of the required curriculum,” says Dr. Epstein. “It targets students and residents working in clinical settings at an advanced level, and it also has a faculty component. … We are trying to transform and heal the informal curriculum, not just immunize students against its toxicity.”

In the Thick of It

All this sounds as if it might benefit hospital practice, according to the hospitalists interviewed for this story. All three believe that mindfulness can be cultivated. Dr. Ali believes the aforementioned forces acting on hospitalists require that hospitalists work at their top capacities, but prioritizing remains essential. He believes one way a hospitalist can cultivate mindfulness in the patient-physician relationship is to avoid burnout in any way that works. Having been a hospitalist for almost 10 years, he discusses this with his medical students and residents. In addition to his hospitalist practice and teaching, Dr. Ali does patient-related quality work, which refreshes his energy.

Dr. Ferguson also thinks mindful practice can be cultivated. “I took cues from the nursing profession in realizing that you do have to care for all aspects of the patient,” she says. “But you can learn this from mentors and people who are successful: people you can emulate, shadow, and follow.”

For her, such a person is Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Dr. Cooper, both a practicing internist and a researcher, studies and teaches about communication between physicians and minorities—that is, how physicians interact with people of the same or different races and ethnicities. Dr. Ferguson says she feels fortunate to have adopted a mindful awareness in that regard.

As director of the medicine clerkship, Dr. Lang came into contact with Dr. Epstein’s project through her Dean’s Teaching Fellowship, a competitive program at the URSM for faculty members who have a special interest in education.

“The discussions with other educators and clinicians really got me thinking about how my own feelings, whether they had to do with a patient or anything else in life, affect my decision-making,” says Dr. Lang. “You see the phenomenon in residency where you’re in morning report when the residents present a patient and everyone is sitting around a table—not involved with the patient—making judgments about what they should have done. It’s so much easier when you’re not involved [in the situation].”

Though Dr. Lang thinks there are a lot of reasons for that, “part of it is that you are not in the excitement of the moment. And the other factor is that when you’re presenting a patient to a group, you wouldn’t convey your own emotions, what else was going on, what were the competing pressures. Even if you have a wonderful intellect and clinical reasoning skills, you might make the wrong decision when you’re in the thick of the situation.”

Mindful Hospital Practice

Dr. Lang has seen a number of outcomes from her study of mindful practice. It has made her aware of her biases and has taught her to say, in certain cases, “OK, I need to think through the problem again to make sure I’m not changing my judgment about what we should be doing clinically based on how I’m feeling about a patient.”

Dr. Lang sometimes asks herself, “How am I feeling about this? Did that wear me down?” Or, sometimes the opposite can occur. A patient can make you feel “puffed up, where they are so complimentary and make you feel so good that you think that every decision you make is perfect,” she explains.

What Dr. Lang has learned about herself has helped her recognize when she might have prematurely closed a differential diagnosis or come to a conclusion too quickly simply because the patient appeared to agree with her clinical assessment.

Dr. Lang also thinks being a mindful physician has made her a better physician and that she is providing better care that results in better outcomes. “I definitely communicate better with my patients. … I think my relationships with my patients have significantly improved.”

What is her recommendation for how her hospitalist colleagues can learn to practice mindfully? “It’s a practice, and it’s a matter of practice,” says Dr. Lang. “It’s not something you get overnight. It’s a matter of every day, every encounter, taking the time before entering the patient’s room to pause, put things aside, and be present with the patient. And then, at the end of the day, take some time to reflect.”

How does education for mindfulness differ from her original medical training? “I don’t think you’re really ever taught how to manage your emotions when you’ve just made a medical error and you are distraught,” says Dr. Lang, “or how to manage doing that when your pager is going off like crazy and yet you need to sit down and be present with your patient. And that’s the kind of thing that ends up being in your way of being the best physician you can be.” TH

References

- Borrell-Carrió F, Epstein RM. Preventing errors in clinical practice: a call for self-awareness. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:310-316.

- Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):387-396.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999 Sep;282(9):833-839.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002 Jan 9;287(2):226-235.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (I): technical competence, evidence-based medicine and relationship-centered care. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21:1-9.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (II): cultivating habits of mind. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21:11-17.

- O’Donnell JF, Rabow MW, Remen RN. The healer’s art: awakening the heart of medicine. Medical Encounter: Newsletter of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. 2007;21, No 1.