User login

Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer

• whether a photograph was enclosed

• whether additional items were enclosed (eg, gifts, drawings)

• whether the letter was rejected by prison authorities

• the writer’s purpose.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Letters were assigned to 1 of 5 categories:

Acquaintance letters sought ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer. They focused largely on conveying information about the writer.

Show of support letters also sought an ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer, but instead focused on him, not the writer.

Romance letters used words that conveyed romantic or non-platonic affection.

Spiritual letters gave advice to the murderer with a religious tone.

Words of wisdom letters offered advice but lacked a religious tone.

Given the nonstandardized nature of categorization and the lack of a formal questionnaire, we were unable to perform an exploratory factor analysis on our categorizations. Inter-rater reliability of letter categorization was 0.79.

Results: Writer profiles, purpose for writing

In all, we reviewed 819 letters:

• Thirty-five letters were excluded because they were written by family members, children, or other prisoners

• Of the remaining 784 letters, there were 333 unique writers

• Two-hundred sixty letters were written by women, 61 by men; 2 were co-written by both sexes; sex could not be determined for 10.

Women were more likely than men to write a letter (P = .014) and to write ≥3 letters (P = .001). The age of the writer was determined for 117 (35.1%) letters; mean age was 27.8 (± 8.9) years (range, 18 to 59 years).

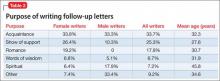

The purpose of the letters differed by sex (P < .001) but not by the writer’s age (P = .058). Women were more likely than men to write letters categorized as “Acquaintance,” “Romance,” and “Show of support”; in contrast, men were more likely than women to write a letter categorized as “Spiritual” (Table 1). Approximately 95% of letters were handwritten. Letters averaged 3 pages (range, 1 to 16 pages).

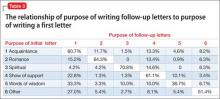

Two-hundred sixteen writers wrote a single letter; 53 wrote 2 letters; 18 wrote 3 letters; 11 wrote 4 letters; 30 wrote 5 to 10 letters; and 9 wrote 11 to 43 letters. The purpose of follow-up letters was associated with the age of the writer (P < .001) and with the writer’s sex (P < .001). Women were more likely to write “Show of support” and “Romance” follow-up letters; men were more likely to write “Spiritual” follow-up letters (Table 2).

Results suggested that the purpose of the initial letter was a reasonable predictor of the purpose of follow-up letters (P < .001) (Table 3). The murderer never responded to any letters. Letters were most often written from his state of incarceration; next, from contiguous states; then, from non-contiguous states; and, last, from international locations (P < .001).

Of the initial letters from writers who wrote ≥10, 60% were categorized as “Acquaintance” and 20% as “Romance.” The writer who wrote the most letters (43) moved during the course of her letter-writing to live in the same state as the murderer; she stated in her letters that she did so to be closer to him and to be able to attend his court hearings. Four other writers, each of whom wrote >5 letters, stated that they had traveled to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend some of his hearings in person.

Composite examples of more common categories of letters

Names and other pertinent identifying information have been changed.

Acquaintance. Hi, Steve. I’ve been following your case and just wanted to write you so that maybe we could be friends or keep in touch since you’re probably pretty bored. I’m a 27-year-old college student studying marketing and working at Applebee’s as a waitress (for now) until I can land my dream job. I’ve enclosed a picture of me and my dachshund along with a photo of my favorite beach in the world. Write me back if you want. Jenny.

Show of support. Steve: I’ve been really worried about you since first seeing you on TV. You look different lately and I hope they’re treating you OK and feeding you decent food. In case they’re not, I’ve enclosed a little something to buy yourself a treat. Just know that there are many of us that care about you and are really pulling for you to be strong in this tough situation you’re in. Yours truly, Karen.

Romance. Dearest Steven: My mind has been filled with thoughts of you and of us since I last saw you in my dreams! Be strong, because you are going to beat this once they understand that you are not responsible for what happened! Don’t you see, sweetie, the system failed you, and now you’re caught up in something that you will soon overcome. When I think of the day that you get released, and how we’ll be able to settle down somewhere together, it gets me incredibly excited. You and I are meant to be together, because I understand you and can help you get better. I love you, Steven! Please write me back so that I know we’re on the same page about our plans for the future. Love, ♥ Your sweetie, Rachel.

Spiritual. Dear Child of God: The Lord has a plan for you. I know that things right now might be confusing, and you’re in a black place, but He is there right beside you. If you need some reading materials to give you comfort, just let me know and I can get a Bible to you along with some other books to give you solace and strengthen your walk with Him. God forgives you and he loves you so much! Much love in Christ, Mary.

Discussion

Given that the mass murderer in this study was a young man, it is not surprising that 78% of writers of initial letters were women. However, it is interesting that, among women’s initial letters, 44% were “Acquaintance” letters and only 15% were categorized as “Romance.”

Given the severity of the murderer’s crime, it is remarkable that he received only 1 “Hate mail” letter.

Initial “Spiritual” letters were more likely to be followed by letters of the same category than any other category; “Romance” letters were a close second. This demonstrates the consistent efforts of writers in these 2 categories. Highly persistent writers (≥10 letters) were most likely to fall into “Acquaintance” and “Romance” categories. The persistence of these writers is remarkable, in view of the fact that none of their letters were answered. We hypothesize that the killer did not reply because he had no interest in correspondence.

Similarities to stalking. Given that 9 writers wrote >10 letters each and 2 wrote >20 each, elements of their behavior are not unlike what is seen in stalkers.3 Consistent with the stalking literature and Mullen et al4 stalker typology, many writers in this study appeared to seek intimacy with the perpetrator through “Romance” or “Show of support” letters, and might be akin to Mullen’s so-called intimacy-seeking stalker. Such stalkers’ behavior arises out of loneliness, with a strong desire for a relationship with the target; a significant percentage of such stalkers suffer a delusional disorder.

Mullen’s so-called incompetent suitor stalker is similar to the intimacy-seeking type but, instead, has an interest in a short-term relationship and is far less persistent in his (her) stalking behavior4; this type might apply to the writers in this study who wrote >1 but <10 letters.

Two additional observations also are notable when trying to characterize people who write letters: (1) A high percentage of people who stalk a celebrity suffer a psychotic disorder5,6; (2) 4 letter-writers traveled, and 1 relocated, to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend his hearings and be closer to him.

This study has limitations:

• categorization of letters is inherently subjective and the categories themselves were created by the researchers

• the nature and categorization of such letters might vary considerably with the age and sex of the violent criminal; our findings in this case are not generalizable.

Last, researchers who plan to study writers of letters to incarcerated criminals should consider sending a personality test and other questionnaires to those writers to understand this population better.

Treatment considerations

Psychiatrists treating patients who seek a romantic attachment with a violent person should consider psychotherapy as a means of treating possible character pathology. The desire for romance with a violent criminal was greater among repeat writers (20%) than in initial letters (15%), suggesting that people who have a strong inclination to associate with a violent person might benefit from exploring romantic feelings in therapy. Specifically, therapists would be wise to explore with such patients the possibility that they experienced violence or verbal abuse in childhood or adulthood.

To the extent that evidence of prior abuse exists, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might be appropriate; specialized therapy for men and women with a history of abuse might be indicated. It is important to provide validation for patients who are victims when they describe their abuse, and to stress that they did nothing to provoke the violence. Furthermore, investigation of why the patient feels drawn romantically toward a violent criminal is helpful, as well as an examination of how such behavior is self-defeating.

There might be value in having patients keep a journal in lieu of actually sending letters; there is evidence that “journaling” can reduce substance use recidivism.7 This work can be performed in conjunction with group or individual psychotherapy that addresses any history of abuse and subsequent PTSD.

Many patients are reluctant to discuss their romantic feelings toward a violent criminal until the psychiatrist has established a strong doctor−patient relationship. Last, clinicians should not hesitate to refer these patients to a therapist who specializes in domestic violence.

Related Resource

• Marazziti D, Falaschi V, Lombardi A, et al. Stalking: a neurobiological perspective. Riv Psichiatr. 2015;50(1):12-18.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mouradian VE. Women’s stay-leave decisions in relationships involving intimate partner violence. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley Centers for Women Publications; 2004:3,4.

2. Bell KM, Naugle AE. Understanding stay/leave decisions in violent relationships: a behavior analytic approach. Behav Soc Issues. 2005;14(1):21-46.

3. Westrup D, Fremouw WJ. Stalking behavior: a literature review and suggested functional analytic assessment technology. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3: 255-274.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

5. West SG, Friedman SH. These boots are made for stalking: characteristics of female stalkers. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2008;5(8):37-42.

6. Nadkarni R, Grubin D. Stalking: why do people do it? BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1486-1487.

7. Proctor SL, Hoffmann NG, Allison S. The effectiveness of interactive journaling in reducing recidivism among substance-dependent jail inmates. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2012;56(2):317-332.

Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer

• whether a photograph was enclosed

• whether additional items were enclosed (eg, gifts, drawings)

• whether the letter was rejected by prison authorities

• the writer’s purpose.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Letters were assigned to 1 of 5 categories:

Acquaintance letters sought ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer. They focused largely on conveying information about the writer.

Show of support letters also sought an ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer, but instead focused on him, not the writer.

Romance letters used words that conveyed romantic or non-platonic affection.

Spiritual letters gave advice to the murderer with a religious tone.

Words of wisdom letters offered advice but lacked a religious tone.

Given the nonstandardized nature of categorization and the lack of a formal questionnaire, we were unable to perform an exploratory factor analysis on our categorizations. Inter-rater reliability of letter categorization was 0.79.

Results: Writer profiles, purpose for writing

In all, we reviewed 819 letters:

• Thirty-five letters were excluded because they were written by family members, children, or other prisoners

• Of the remaining 784 letters, there were 333 unique writers

• Two-hundred sixty letters were written by women, 61 by men; 2 were co-written by both sexes; sex could not be determined for 10.

Women were more likely than men to write a letter (P = .014) and to write ≥3 letters (P = .001). The age of the writer was determined for 117 (35.1%) letters; mean age was 27.8 (± 8.9) years (range, 18 to 59 years).

The purpose of the letters differed by sex (P < .001) but not by the writer’s age (P = .058). Women were more likely than men to write letters categorized as “Acquaintance,” “Romance,” and “Show of support”; in contrast, men were more likely than women to write a letter categorized as “Spiritual” (Table 1). Approximately 95% of letters were handwritten. Letters averaged 3 pages (range, 1 to 16 pages).

Two-hundred sixteen writers wrote a single letter; 53 wrote 2 letters; 18 wrote 3 letters; 11 wrote 4 letters; 30 wrote 5 to 10 letters; and 9 wrote 11 to 43 letters. The purpose of follow-up letters was associated with the age of the writer (P < .001) and with the writer’s sex (P < .001). Women were more likely to write “Show of support” and “Romance” follow-up letters; men were more likely to write “Spiritual” follow-up letters (Table 2).

Results suggested that the purpose of the initial letter was a reasonable predictor of the purpose of follow-up letters (P < .001) (Table 3). The murderer never responded to any letters. Letters were most often written from his state of incarceration; next, from contiguous states; then, from non-contiguous states; and, last, from international locations (P < .001).

Of the initial letters from writers who wrote ≥10, 60% were categorized as “Acquaintance” and 20% as “Romance.” The writer who wrote the most letters (43) moved during the course of her letter-writing to live in the same state as the murderer; she stated in her letters that she did so to be closer to him and to be able to attend his court hearings. Four other writers, each of whom wrote >5 letters, stated that they had traveled to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend some of his hearings in person.

Composite examples of more common categories of letters

Names and other pertinent identifying information have been changed.

Acquaintance. Hi, Steve. I’ve been following your case and just wanted to write you so that maybe we could be friends or keep in touch since you’re probably pretty bored. I’m a 27-year-old college student studying marketing and working at Applebee’s as a waitress (for now) until I can land my dream job. I’ve enclosed a picture of me and my dachshund along with a photo of my favorite beach in the world. Write me back if you want. Jenny.

Show of support. Steve: I’ve been really worried about you since first seeing you on TV. You look different lately and I hope they’re treating you OK and feeding you decent food. In case they’re not, I’ve enclosed a little something to buy yourself a treat. Just know that there are many of us that care about you and are really pulling for you to be strong in this tough situation you’re in. Yours truly, Karen.

Romance. Dearest Steven: My mind has been filled with thoughts of you and of us since I last saw you in my dreams! Be strong, because you are going to beat this once they understand that you are not responsible for what happened! Don’t you see, sweetie, the system failed you, and now you’re caught up in something that you will soon overcome. When I think of the day that you get released, and how we’ll be able to settle down somewhere together, it gets me incredibly excited. You and I are meant to be together, because I understand you and can help you get better. I love you, Steven! Please write me back so that I know we’re on the same page about our plans for the future. Love, ♥ Your sweetie, Rachel.

Spiritual. Dear Child of God: The Lord has a plan for you. I know that things right now might be confusing, and you’re in a black place, but He is there right beside you. If you need some reading materials to give you comfort, just let me know and I can get a Bible to you along with some other books to give you solace and strengthen your walk with Him. God forgives you and he loves you so much! Much love in Christ, Mary.

Discussion

Given that the mass murderer in this study was a young man, it is not surprising that 78% of writers of initial letters were women. However, it is interesting that, among women’s initial letters, 44% were “Acquaintance” letters and only 15% were categorized as “Romance.”

Given the severity of the murderer’s crime, it is remarkable that he received only 1 “Hate mail” letter.

Initial “Spiritual” letters were more likely to be followed by letters of the same category than any other category; “Romance” letters were a close second. This demonstrates the consistent efforts of writers in these 2 categories. Highly persistent writers (≥10 letters) were most likely to fall into “Acquaintance” and “Romance” categories. The persistence of these writers is remarkable, in view of the fact that none of their letters were answered. We hypothesize that the killer did not reply because he had no interest in correspondence.

Similarities to stalking. Given that 9 writers wrote >10 letters each and 2 wrote >20 each, elements of their behavior are not unlike what is seen in stalkers.3 Consistent with the stalking literature and Mullen et al4 stalker typology, many writers in this study appeared to seek intimacy with the perpetrator through “Romance” or “Show of support” letters, and might be akin to Mullen’s so-called intimacy-seeking stalker. Such stalkers’ behavior arises out of loneliness, with a strong desire for a relationship with the target; a significant percentage of such stalkers suffer a delusional disorder.

Mullen’s so-called incompetent suitor stalker is similar to the intimacy-seeking type but, instead, has an interest in a short-term relationship and is far less persistent in his (her) stalking behavior4; this type might apply to the writers in this study who wrote >1 but <10 letters.

Two additional observations also are notable when trying to characterize people who write letters: (1) A high percentage of people who stalk a celebrity suffer a psychotic disorder5,6; (2) 4 letter-writers traveled, and 1 relocated, to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend his hearings and be closer to him.

This study has limitations:

• categorization of letters is inherently subjective and the categories themselves were created by the researchers

• the nature and categorization of such letters might vary considerably with the age and sex of the violent criminal; our findings in this case are not generalizable.

Last, researchers who plan to study writers of letters to incarcerated criminals should consider sending a personality test and other questionnaires to those writers to understand this population better.

Treatment considerations

Psychiatrists treating patients who seek a romantic attachment with a violent person should consider psychotherapy as a means of treating possible character pathology. The desire for romance with a violent criminal was greater among repeat writers (20%) than in initial letters (15%), suggesting that people who have a strong inclination to associate with a violent person might benefit from exploring romantic feelings in therapy. Specifically, therapists would be wise to explore with such patients the possibility that they experienced violence or verbal abuse in childhood or adulthood.

To the extent that evidence of prior abuse exists, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might be appropriate; specialized therapy for men and women with a history of abuse might be indicated. It is important to provide validation for patients who are victims when they describe their abuse, and to stress that they did nothing to provoke the violence. Furthermore, investigation of why the patient feels drawn romantically toward a violent criminal is helpful, as well as an examination of how such behavior is self-defeating.

There might be value in having patients keep a journal in lieu of actually sending letters; there is evidence that “journaling” can reduce substance use recidivism.7 This work can be performed in conjunction with group or individual psychotherapy that addresses any history of abuse and subsequent PTSD.

Many patients are reluctant to discuss their romantic feelings toward a violent criminal until the psychiatrist has established a strong doctor−patient relationship. Last, clinicians should not hesitate to refer these patients to a therapist who specializes in domestic violence.

Related Resource

• Marazziti D, Falaschi V, Lombardi A, et al. Stalking: a neurobiological perspective. Riv Psichiatr. 2015;50(1):12-18.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer

• whether a photograph was enclosed

• whether additional items were enclosed (eg, gifts, drawings)

• whether the letter was rejected by prison authorities

• the writer’s purpose.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Letters were assigned to 1 of 5 categories:

Acquaintance letters sought ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer. They focused largely on conveying information about the writer.

Show of support letters also sought an ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer, but instead focused on him, not the writer.

Romance letters used words that conveyed romantic or non-platonic affection.

Spiritual letters gave advice to the murderer with a religious tone.

Words of wisdom letters offered advice but lacked a religious tone.

Given the nonstandardized nature of categorization and the lack of a formal questionnaire, we were unable to perform an exploratory factor analysis on our categorizations. Inter-rater reliability of letter categorization was 0.79.

Results: Writer profiles, purpose for writing

In all, we reviewed 819 letters:

• Thirty-five letters were excluded because they were written by family members, children, or other prisoners

• Of the remaining 784 letters, there were 333 unique writers

• Two-hundred sixty letters were written by women, 61 by men; 2 were co-written by both sexes; sex could not be determined for 10.

Women were more likely than men to write a letter (P = .014) and to write ≥3 letters (P = .001). The age of the writer was determined for 117 (35.1%) letters; mean age was 27.8 (± 8.9) years (range, 18 to 59 years).

The purpose of the letters differed by sex (P < .001) but not by the writer’s age (P = .058). Women were more likely than men to write letters categorized as “Acquaintance,” “Romance,” and “Show of support”; in contrast, men were more likely than women to write a letter categorized as “Spiritual” (Table 1). Approximately 95% of letters were handwritten. Letters averaged 3 pages (range, 1 to 16 pages).

Two-hundred sixteen writers wrote a single letter; 53 wrote 2 letters; 18 wrote 3 letters; 11 wrote 4 letters; 30 wrote 5 to 10 letters; and 9 wrote 11 to 43 letters. The purpose of follow-up letters was associated with the age of the writer (P < .001) and with the writer’s sex (P < .001). Women were more likely to write “Show of support” and “Romance” follow-up letters; men were more likely to write “Spiritual” follow-up letters (Table 2).

Results suggested that the purpose of the initial letter was a reasonable predictor of the purpose of follow-up letters (P < .001) (Table 3). The murderer never responded to any letters. Letters were most often written from his state of incarceration; next, from contiguous states; then, from non-contiguous states; and, last, from international locations (P < .001).

Of the initial letters from writers who wrote ≥10, 60% were categorized as “Acquaintance” and 20% as “Romance.” The writer who wrote the most letters (43) moved during the course of her letter-writing to live in the same state as the murderer; she stated in her letters that she did so to be closer to him and to be able to attend his court hearings. Four other writers, each of whom wrote >5 letters, stated that they had traveled to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend some of his hearings in person.

Composite examples of more common categories of letters

Names and other pertinent identifying information have been changed.

Acquaintance. Hi, Steve. I’ve been following your case and just wanted to write you so that maybe we could be friends or keep in touch since you’re probably pretty bored. I’m a 27-year-old college student studying marketing and working at Applebee’s as a waitress (for now) until I can land my dream job. I’ve enclosed a picture of me and my dachshund along with a photo of my favorite beach in the world. Write me back if you want. Jenny.

Show of support. Steve: I’ve been really worried about you since first seeing you on TV. You look different lately and I hope they’re treating you OK and feeding you decent food. In case they’re not, I’ve enclosed a little something to buy yourself a treat. Just know that there are many of us that care about you and are really pulling for you to be strong in this tough situation you’re in. Yours truly, Karen.

Romance. Dearest Steven: My mind has been filled with thoughts of you and of us since I last saw you in my dreams! Be strong, because you are going to beat this once they understand that you are not responsible for what happened! Don’t you see, sweetie, the system failed you, and now you’re caught up in something that you will soon overcome. When I think of the day that you get released, and how we’ll be able to settle down somewhere together, it gets me incredibly excited. You and I are meant to be together, because I understand you and can help you get better. I love you, Steven! Please write me back so that I know we’re on the same page about our plans for the future. Love, ♥ Your sweetie, Rachel.

Spiritual. Dear Child of God: The Lord has a plan for you. I know that things right now might be confusing, and you’re in a black place, but He is there right beside you. If you need some reading materials to give you comfort, just let me know and I can get a Bible to you along with some other books to give you solace and strengthen your walk with Him. God forgives you and he loves you so much! Much love in Christ, Mary.

Discussion

Given that the mass murderer in this study was a young man, it is not surprising that 78% of writers of initial letters were women. However, it is interesting that, among women’s initial letters, 44% were “Acquaintance” letters and only 15% were categorized as “Romance.”

Given the severity of the murderer’s crime, it is remarkable that he received only 1 “Hate mail” letter.

Initial “Spiritual” letters were more likely to be followed by letters of the same category than any other category; “Romance” letters were a close second. This demonstrates the consistent efforts of writers in these 2 categories. Highly persistent writers (≥10 letters) were most likely to fall into “Acquaintance” and “Romance” categories. The persistence of these writers is remarkable, in view of the fact that none of their letters were answered. We hypothesize that the killer did not reply because he had no interest in correspondence.

Similarities to stalking. Given that 9 writers wrote >10 letters each and 2 wrote >20 each, elements of their behavior are not unlike what is seen in stalkers.3 Consistent with the stalking literature and Mullen et al4 stalker typology, many writers in this study appeared to seek intimacy with the perpetrator through “Romance” or “Show of support” letters, and might be akin to Mullen’s so-called intimacy-seeking stalker. Such stalkers’ behavior arises out of loneliness, with a strong desire for a relationship with the target; a significant percentage of such stalkers suffer a delusional disorder.

Mullen’s so-called incompetent suitor stalker is similar to the intimacy-seeking type but, instead, has an interest in a short-term relationship and is far less persistent in his (her) stalking behavior4; this type might apply to the writers in this study who wrote >1 but <10 letters.

Two additional observations also are notable when trying to characterize people who write letters: (1) A high percentage of people who stalk a celebrity suffer a psychotic disorder5,6; (2) 4 letter-writers traveled, and 1 relocated, to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend his hearings and be closer to him.

This study has limitations:

• categorization of letters is inherently subjective and the categories themselves were created by the researchers

• the nature and categorization of such letters might vary considerably with the age and sex of the violent criminal; our findings in this case are not generalizable.

Last, researchers who plan to study writers of letters to incarcerated criminals should consider sending a personality test and other questionnaires to those writers to understand this population better.

Treatment considerations

Psychiatrists treating patients who seek a romantic attachment with a violent person should consider psychotherapy as a means of treating possible character pathology. The desire for romance with a violent criminal was greater among repeat writers (20%) than in initial letters (15%), suggesting that people who have a strong inclination to associate with a violent person might benefit from exploring romantic feelings in therapy. Specifically, therapists would be wise to explore with such patients the possibility that they experienced violence or verbal abuse in childhood or adulthood.

To the extent that evidence of prior abuse exists, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might be appropriate; specialized therapy for men and women with a history of abuse might be indicated. It is important to provide validation for patients who are victims when they describe their abuse, and to stress that they did nothing to provoke the violence. Furthermore, investigation of why the patient feels drawn romantically toward a violent criminal is helpful, as well as an examination of how such behavior is self-defeating.

There might be value in having patients keep a journal in lieu of actually sending letters; there is evidence that “journaling” can reduce substance use recidivism.7 This work can be performed in conjunction with group or individual psychotherapy that addresses any history of abuse and subsequent PTSD.

Many patients are reluctant to discuss their romantic feelings toward a violent criminal until the psychiatrist has established a strong doctor−patient relationship. Last, clinicians should not hesitate to refer these patients to a therapist who specializes in domestic violence.

Related Resource

• Marazziti D, Falaschi V, Lombardi A, et al. Stalking: a neurobiological perspective. Riv Psichiatr. 2015;50(1):12-18.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mouradian VE. Women’s stay-leave decisions in relationships involving intimate partner violence. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley Centers for Women Publications; 2004:3,4.

2. Bell KM, Naugle AE. Understanding stay/leave decisions in violent relationships: a behavior analytic approach. Behav Soc Issues. 2005;14(1):21-46.

3. Westrup D, Fremouw WJ. Stalking behavior: a literature review and suggested functional analytic assessment technology. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3: 255-274.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

5. West SG, Friedman SH. These boots are made for stalking: characteristics of female stalkers. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2008;5(8):37-42.

6. Nadkarni R, Grubin D. Stalking: why do people do it? BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1486-1487.

7. Proctor SL, Hoffmann NG, Allison S. The effectiveness of interactive journaling in reducing recidivism among substance-dependent jail inmates. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2012;56(2):317-332.

1. Mouradian VE. Women’s stay-leave decisions in relationships involving intimate partner violence. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley Centers for Women Publications; 2004:3,4.

2. Bell KM, Naugle AE. Understanding stay/leave decisions in violent relationships: a behavior analytic approach. Behav Soc Issues. 2005;14(1):21-46.

3. Westrup D, Fremouw WJ. Stalking behavior: a literature review and suggested functional analytic assessment technology. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3: 255-274.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

5. West SG, Friedman SH. These boots are made for stalking: characteristics of female stalkers. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2008;5(8):37-42.

6. Nadkarni R, Grubin D. Stalking: why do people do it? BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1486-1487.

7. Proctor SL, Hoffmann NG, Allison S. The effectiveness of interactive journaling in reducing recidivism among substance-dependent jail inmates. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2012;56(2):317-332.