User login

CHICAGO -- Mitral valve endocarditis is a medical-surgical problem that demands a team approach, and the landscape of the disease has changed significantly for the worst in the recent past, according to a presentation at Heart Valve Summit 2012.

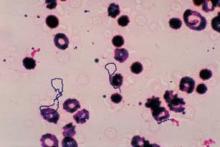

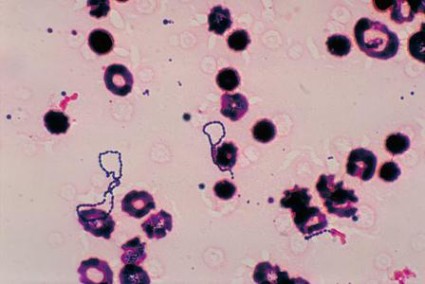

"If you’re lucky enough to have a valve infection with the Strep viridans microorganism, you’re likely to do well," said Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara, director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

On the other hand, patients who’ve been infected with any other type of organism, particularly Staph aureus or its increasingly frequent relative methicillin-resistant Staph aureus, could be in real trouble.

"There’s no question that these organisms are smarter than we are and can lead to destruction of the valve and death of the patient, despite our best intentions," said Dr. O’Gara. He described the evolving epidemiology, natural history, and indications for surgery for this disease to this educational program of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) and the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF).

"Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, and worldwide, among centers with an interest in the care of patients with endocarditis, 6-month mortality rates still approach 25%," he said. This is close to the mortality rate of a type A aortic dissection, so it is by no means trivial. Early surgery is now performed on many who present with the disease in early stages, and perioperative mortality is 12%-20%.

It is a challenge to manage a patient who is asymptomatic with respect to heart failure but who has a large mobile vegetation involving the anterior mitral leaflet, said Dr. O’Gara. Vegetations in this location are the most prone to embolize.

"This is the common question now posed to consulting cardiologists: Does my patient require early surgery for prevention of embolic complications? We don’t really get asked too much any more: ‘Does my patient need early surgery because they’ve developed heart failure?’ I guess we’re much more confident in proceeding under those circumstances."

He discussed considerations for surgery, including the level of local surgical expertise. The intervention is complex and delicate. "This is not something for the faint of heart," said Dr. O’Gara.

In the early time frame following presentation, there is a relationship between the size of the vegetation and the risk of embolization.

The risk of stroke drops rapidly after initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Patients who develop stroke as a complication of endocarditis typically do so the day before, the day of, or the day after presentation, he said. Stroke risk continues to drop quickly in the first 2 weeks after initiation of antibiotics, and by week 5 it’s almost nil.

"If you’re thinking about intervention for prevention of stroke, it makes sense to do so in the first week, after identification of a patient at risk with a large mobile vegetation. It makes much less sense to do so in weeks 2 or 3."

The size of the vegetation alone may dictate mortality. A size of 1.5 cm or greater is associated with increased risk of death at 1 year in the setting of native valve endocarditis.

The good news is that event-free survival rates have been shown to be much better for those who undergo surgery in the first 7 days after presentation with high-risk native, left-sided endocarditis. In-hospital mortality as a function of early surgery appears to have declined over the course of time.

"So, in summary, I think for our management considerations, it’s early diagnosis, risk stratification, a heart team approach, consider early surgery, particularly if you have the operative expertise. The early risk of re-infection in implanted prosthetic material is very low," Dr. O’Gara said.

Dr. O’Gara disclosed ties with the Data Safety Monitoring Board and Lantheus Medical Imaging.

CHICAGO -- Mitral valve endocarditis is a medical-surgical problem that demands a team approach, and the landscape of the disease has changed significantly for the worst in the recent past, according to a presentation at Heart Valve Summit 2012.

"If you’re lucky enough to have a valve infection with the Strep viridans microorganism, you’re likely to do well," said Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara, director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

On the other hand, patients who’ve been infected with any other type of organism, particularly Staph aureus or its increasingly frequent relative methicillin-resistant Staph aureus, could be in real trouble.

"There’s no question that these organisms are smarter than we are and can lead to destruction of the valve and death of the patient, despite our best intentions," said Dr. O’Gara. He described the evolving epidemiology, natural history, and indications for surgery for this disease to this educational program of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) and the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF).

"Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, and worldwide, among centers with an interest in the care of patients with endocarditis, 6-month mortality rates still approach 25%," he said. This is close to the mortality rate of a type A aortic dissection, so it is by no means trivial. Early surgery is now performed on many who present with the disease in early stages, and perioperative mortality is 12%-20%.

It is a challenge to manage a patient who is asymptomatic with respect to heart failure but who has a large mobile vegetation involving the anterior mitral leaflet, said Dr. O’Gara. Vegetations in this location are the most prone to embolize.

"This is the common question now posed to consulting cardiologists: Does my patient require early surgery for prevention of embolic complications? We don’t really get asked too much any more: ‘Does my patient need early surgery because they’ve developed heart failure?’ I guess we’re much more confident in proceeding under those circumstances."

He discussed considerations for surgery, including the level of local surgical expertise. The intervention is complex and delicate. "This is not something for the faint of heart," said Dr. O’Gara.

In the early time frame following presentation, there is a relationship between the size of the vegetation and the risk of embolization.

The risk of stroke drops rapidly after initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Patients who develop stroke as a complication of endocarditis typically do so the day before, the day of, or the day after presentation, he said. Stroke risk continues to drop quickly in the first 2 weeks after initiation of antibiotics, and by week 5 it’s almost nil.

"If you’re thinking about intervention for prevention of stroke, it makes sense to do so in the first week, after identification of a patient at risk with a large mobile vegetation. It makes much less sense to do so in weeks 2 or 3."

The size of the vegetation alone may dictate mortality. A size of 1.5 cm or greater is associated with increased risk of death at 1 year in the setting of native valve endocarditis.

The good news is that event-free survival rates have been shown to be much better for those who undergo surgery in the first 7 days after presentation with high-risk native, left-sided endocarditis. In-hospital mortality as a function of early surgery appears to have declined over the course of time.

"So, in summary, I think for our management considerations, it’s early diagnosis, risk stratification, a heart team approach, consider early surgery, particularly if you have the operative expertise. The early risk of re-infection in implanted prosthetic material is very low," Dr. O’Gara said.

Dr. O’Gara disclosed ties with the Data Safety Monitoring Board and Lantheus Medical Imaging.

CHICAGO -- Mitral valve endocarditis is a medical-surgical problem that demands a team approach, and the landscape of the disease has changed significantly for the worst in the recent past, according to a presentation at Heart Valve Summit 2012.

"If you’re lucky enough to have a valve infection with the Strep viridans microorganism, you’re likely to do well," said Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara, director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

On the other hand, patients who’ve been infected with any other type of organism, particularly Staph aureus or its increasingly frequent relative methicillin-resistant Staph aureus, could be in real trouble.

"There’s no question that these organisms are smarter than we are and can lead to destruction of the valve and death of the patient, despite our best intentions," said Dr. O’Gara. He described the evolving epidemiology, natural history, and indications for surgery for this disease to this educational program of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) and the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF).

"Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, and worldwide, among centers with an interest in the care of patients with endocarditis, 6-month mortality rates still approach 25%," he said. This is close to the mortality rate of a type A aortic dissection, so it is by no means trivial. Early surgery is now performed on many who present with the disease in early stages, and perioperative mortality is 12%-20%.

It is a challenge to manage a patient who is asymptomatic with respect to heart failure but who has a large mobile vegetation involving the anterior mitral leaflet, said Dr. O’Gara. Vegetations in this location are the most prone to embolize.

"This is the common question now posed to consulting cardiologists: Does my patient require early surgery for prevention of embolic complications? We don’t really get asked too much any more: ‘Does my patient need early surgery because they’ve developed heart failure?’ I guess we’re much more confident in proceeding under those circumstances."

He discussed considerations for surgery, including the level of local surgical expertise. The intervention is complex and delicate. "This is not something for the faint of heart," said Dr. O’Gara.

In the early time frame following presentation, there is a relationship between the size of the vegetation and the risk of embolization.

The risk of stroke drops rapidly after initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Patients who develop stroke as a complication of endocarditis typically do so the day before, the day of, or the day after presentation, he said. Stroke risk continues to drop quickly in the first 2 weeks after initiation of antibiotics, and by week 5 it’s almost nil.

"If you’re thinking about intervention for prevention of stroke, it makes sense to do so in the first week, after identification of a patient at risk with a large mobile vegetation. It makes much less sense to do so in weeks 2 or 3."

The size of the vegetation alone may dictate mortality. A size of 1.5 cm or greater is associated with increased risk of death at 1 year in the setting of native valve endocarditis.

The good news is that event-free survival rates have been shown to be much better for those who undergo surgery in the first 7 days after presentation with high-risk native, left-sided endocarditis. In-hospital mortality as a function of early surgery appears to have declined over the course of time.

"So, in summary, I think for our management considerations, it’s early diagnosis, risk stratification, a heart team approach, consider early surgery, particularly if you have the operative expertise. The early risk of re-infection in implanted prosthetic material is very low," Dr. O’Gara said.

Dr. O’Gara disclosed ties with the Data Safety Monitoring Board and Lantheus Medical Imaging.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM HEART VALVE SUMMIT 2012