User login

Ms. C, age 44, has a history of hypertension, chronic shoulder pain associated with a motor vehicle accident almost 2 decades ago, and major depressive disorder (MDD). Her medication regimen includes losartan, 100 mg/d; atenolol, 25 mg/d; gabapentin, 100 mg, 3 times a day; sertraline, 100 mg/d; and naproxen, 500 mg, twice a day as needed for pain. She does not take opioids for pain control because she had a poor response when used in the past. Ms. C denies muscle pain or tenderness but describes pain in nonspecific areas of her arm, shoulder, neck, and chest. Ms. C reports poor quality of sleep and early morning awakenings, which she attributes to her unmanaged pain. Her last appointment with a psychiatrist was “many, many months ago.”

A reciprocal relationship exists between depression and pain. A 2-year, population-based, prospective, observational study of 3,654 patients showed that pain at baseline was an independent predictor of depression and a depression diagnosis was a predictor of developing pain within 2 years.1 Patients with MDD might complain of physical symptoms, such as constipation, generalized aches, frequent headache, and fatigue, many of which overlap with chronic pain disorders. Therefore, a thorough symptom assessment and history is vital for an accurate diagnosis. To decrease polypharmacy and pill burden, optimal treatment should employ agents that treat both conditions.

Using antidepressants to treat pain disorders

Several antidepressants have been studied for managing pain disorders including:

- fibromyalgia

- diabetic neuropathy

- neuropathic pain

- postherpetic neuralgia

- migraine prophylaxis

- chronic musculoskeletal pain.

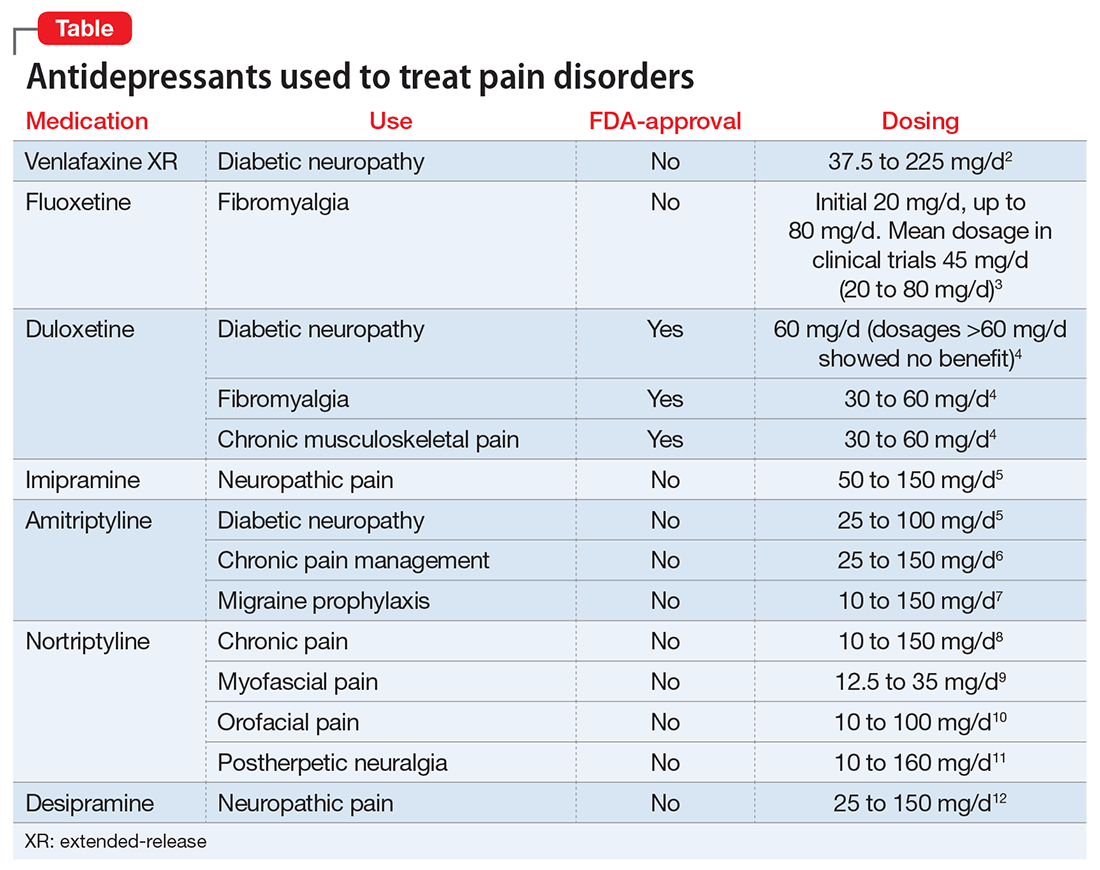

Antidepressants that treat both depression and chronic neuropathic pain include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (Table).2-12 Notably, most antidepressants studied for pain management are used off-label; duloxetine is the only medication with an FDA indication for MDD and pain disorders.

The hypothesized mechanism of action is dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, based on the monoamine hypothesis of depression and pain signaling dysfunction in neuropathic pain. Antidepressants, such as TCAs and SNRIs, address pain by increasing the synaptic concentration of norepinephrine and/or serotonin in the dorsal horn, thereby inhibiting the release of excitatory neurotransmitters and blunting pain pathways.13

TCAs used to treat comorbid depression and pain conditions include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, and desipramine.14 TCAs are cost-effective medications for managing neuropathy and headache; however, the dosages used for pain tend to be lower than those typically used for depression.

TCAs are not commonly prescribed for depression because of their side-effect profile and poor tolerability. TCAs are contraindicated in patients with cardiac conduction abnormalities, epilepsy, and narrow-angle glaucoma. Common adverse effects include dry mouth, sweating, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, sedation, weight gain, urinary retention, and constipation. These adverse effects limit their use and have organizations, such as the American Geriatric Society, to caution against their use in geriatric patients.

SNRIs that have been studied for pain disorders include venlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran.2 Of note, milnacipran is not FDA-approved for MDD, but its L-enantiomer, levomilnacipran, is. Unlike duloxetine and venlafaxine, both milnacipran and levomilnacipran are not available as a generic formulation, therefore they have a higher patient cost. The SNRI dosages used for pain management tend to be similar to those used for MDD, indicating that the target dosage may be effective for both depressive and pain symptoms.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Compared with data available supporting the use of TCAs and SNRIs for pain management, the data for SSRI are sparse. Studies have evaluated fluoxetine, paroxetine, and citalopram for pain, with the most promising data supporting fluoxetine.2 Fluoxetine, 10 to 80 mg/d, has been evaluated in randomized, placebo-controlled trials for pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (n = 3), painful diabetic neuropathy (n = 1), and facial pain (n = 1). Fluoxetine was more effective than placebo at controlling pain in 2 fibromyalgia studies (dosage range, 10 to 80 mg/d) and 1 facial pain study (dosage, 20 mg/d).2

CASE CONTINUED

When evaluating potential treatment options, it is noted that Ms. C is prescribed sertraline, 200 mg/d, but has been taking a lower dosage. Ms. C states that she has been taking sertraline, 100 mg every morning, for months, and noticed some minor initial improvements in mood, but still has days when she don’t feel like doing anything. She fills out a depression rating scale classifying her current depression as moderately severe. Today she rates her pain as 7 out of 10. Suboptimal control of her depression may require a dosage increase; however, perhaps a change in therapy is warranted. It may be prudent to switch Ms. C to an SNRI, such as duloxetine, an agent that can address her depression and provide additional benefits of pain control.

Switching from a SSRI to duloxetine has been shown to be effective when targeting pain symptoms in patients with comorbid MDD. In addition, improvements in pain scores have been seen after a switch to duloxetine in patients with depression with nonresponse or partial response to a SSRI.15

Studies support the decision to change Ms. C’s medication from sertraline to duloxetine, despite an inadequate therapeutic trial of the SSRI.

Using pain medication to treat depression

Conversely, the use of pain medications to treat depression also has been studied. The most notable data supports the use of ketamine, an anesthetic. IV ketamine is well documented for treating pain and, in recent years, has been evaluated for MDD in several small studies. Results show that IV ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, produced a rapid response in depressed patients.16 For pain conditions studies support the use of ketamine as an IV push, continuous infusion, intermittent infusion, as well as oral administration, for many conditions, including acute and postoperative pain, chronic regional pain, and neuropathic pain. However, there is little evidence evaluating ketamine’s effect on both pain scores and depression symptoms in patients such as Ms. C.

1. Chou KL. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression in older adults: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):115-123.

2. Lee YC, Chen PP. A review of SSRIs and SNRIs in neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(17):2813-2825.

3. Arnold LM, Hess EV, Hudson JI, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):191-197.

4. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lily and Company; 2015.

5. Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al; American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine; American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1758-1765.

6. McQuay HJ, Carroll D, Glynn CJ. Low dose amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Anaesthesia. 1992;47(8):646-652.

7. Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al; European Federation of Neurological Societies. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine—revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):968-981.

8. Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Williams RA, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of nortriptyline for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1998;76(3):287-296.

9. Haviv Y, Rettman A, Aframian D, et al. Myofascial pain: an open study on the pharmacotherapeutic response to stepped treatment with tricyclic antidepressants and gabapentin. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2015;29(2):144-151.

10. Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM. Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2014;7:99-115.

11. Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA, Pappagallo M, et al. Opioids versus antidepressants in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2002;59(7):1015-1021.

12. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

13. Argoff C. Mechanisms of pain transmission and pharmacologic management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):2019-2031.

14. Haanpää ML, Gourlay GK, Kent JL, et al. Treatment considerations for patients with neuropathic pain and other medical comorbidities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(suppl 3):S15-S25.

15. Perahia DGS, Quail D, Desaiah D, et al. Switching to duloxetine in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor non- and partial-responders: effects on painful physical symptoms of depression. J Psychiatric Res. 2009;43(5):512-518.

16. Caddy C, Amit BH, McCloud TL, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub2.

Ms. C, age 44, has a history of hypertension, chronic shoulder pain associated with a motor vehicle accident almost 2 decades ago, and major depressive disorder (MDD). Her medication regimen includes losartan, 100 mg/d; atenolol, 25 mg/d; gabapentin, 100 mg, 3 times a day; sertraline, 100 mg/d; and naproxen, 500 mg, twice a day as needed for pain. She does not take opioids for pain control because she had a poor response when used in the past. Ms. C denies muscle pain or tenderness but describes pain in nonspecific areas of her arm, shoulder, neck, and chest. Ms. C reports poor quality of sleep and early morning awakenings, which she attributes to her unmanaged pain. Her last appointment with a psychiatrist was “many, many months ago.”

A reciprocal relationship exists between depression and pain. A 2-year, population-based, prospective, observational study of 3,654 patients showed that pain at baseline was an independent predictor of depression and a depression diagnosis was a predictor of developing pain within 2 years.1 Patients with MDD might complain of physical symptoms, such as constipation, generalized aches, frequent headache, and fatigue, many of which overlap with chronic pain disorders. Therefore, a thorough symptom assessment and history is vital for an accurate diagnosis. To decrease polypharmacy and pill burden, optimal treatment should employ agents that treat both conditions.

Using antidepressants to treat pain disorders

Several antidepressants have been studied for managing pain disorders including:

- fibromyalgia

- diabetic neuropathy

- neuropathic pain

- postherpetic neuralgia

- migraine prophylaxis

- chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Antidepressants that treat both depression and chronic neuropathic pain include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (Table).2-12 Notably, most antidepressants studied for pain management are used off-label; duloxetine is the only medication with an FDA indication for MDD and pain disorders.

The hypothesized mechanism of action is dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, based on the monoamine hypothesis of depression and pain signaling dysfunction in neuropathic pain. Antidepressants, such as TCAs and SNRIs, address pain by increasing the synaptic concentration of norepinephrine and/or serotonin in the dorsal horn, thereby inhibiting the release of excitatory neurotransmitters and blunting pain pathways.13

TCAs used to treat comorbid depression and pain conditions include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, and desipramine.14 TCAs are cost-effective medications for managing neuropathy and headache; however, the dosages used for pain tend to be lower than those typically used for depression.

TCAs are not commonly prescribed for depression because of their side-effect profile and poor tolerability. TCAs are contraindicated in patients with cardiac conduction abnormalities, epilepsy, and narrow-angle glaucoma. Common adverse effects include dry mouth, sweating, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, sedation, weight gain, urinary retention, and constipation. These adverse effects limit their use and have organizations, such as the American Geriatric Society, to caution against their use in geriatric patients.

SNRIs that have been studied for pain disorders include venlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran.2 Of note, milnacipran is not FDA-approved for MDD, but its L-enantiomer, levomilnacipran, is. Unlike duloxetine and venlafaxine, both milnacipran and levomilnacipran are not available as a generic formulation, therefore they have a higher patient cost. The SNRI dosages used for pain management tend to be similar to those used for MDD, indicating that the target dosage may be effective for both depressive and pain symptoms.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Compared with data available supporting the use of TCAs and SNRIs for pain management, the data for SSRI are sparse. Studies have evaluated fluoxetine, paroxetine, and citalopram for pain, with the most promising data supporting fluoxetine.2 Fluoxetine, 10 to 80 mg/d, has been evaluated in randomized, placebo-controlled trials for pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (n = 3), painful diabetic neuropathy (n = 1), and facial pain (n = 1). Fluoxetine was more effective than placebo at controlling pain in 2 fibromyalgia studies (dosage range, 10 to 80 mg/d) and 1 facial pain study (dosage, 20 mg/d).2

CASE CONTINUED

When evaluating potential treatment options, it is noted that Ms. C is prescribed sertraline, 200 mg/d, but has been taking a lower dosage. Ms. C states that she has been taking sertraline, 100 mg every morning, for months, and noticed some minor initial improvements in mood, but still has days when she don’t feel like doing anything. She fills out a depression rating scale classifying her current depression as moderately severe. Today she rates her pain as 7 out of 10. Suboptimal control of her depression may require a dosage increase; however, perhaps a change in therapy is warranted. It may be prudent to switch Ms. C to an SNRI, such as duloxetine, an agent that can address her depression and provide additional benefits of pain control.

Switching from a SSRI to duloxetine has been shown to be effective when targeting pain symptoms in patients with comorbid MDD. In addition, improvements in pain scores have been seen after a switch to duloxetine in patients with depression with nonresponse or partial response to a SSRI.15

Studies support the decision to change Ms. C’s medication from sertraline to duloxetine, despite an inadequate therapeutic trial of the SSRI.

Using pain medication to treat depression

Conversely, the use of pain medications to treat depression also has been studied. The most notable data supports the use of ketamine, an anesthetic. IV ketamine is well documented for treating pain and, in recent years, has been evaluated for MDD in several small studies. Results show that IV ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, produced a rapid response in depressed patients.16 For pain conditions studies support the use of ketamine as an IV push, continuous infusion, intermittent infusion, as well as oral administration, for many conditions, including acute and postoperative pain, chronic regional pain, and neuropathic pain. However, there is little evidence evaluating ketamine’s effect on both pain scores and depression symptoms in patients such as Ms. C.

Ms. C, age 44, has a history of hypertension, chronic shoulder pain associated with a motor vehicle accident almost 2 decades ago, and major depressive disorder (MDD). Her medication regimen includes losartan, 100 mg/d; atenolol, 25 mg/d; gabapentin, 100 mg, 3 times a day; sertraline, 100 mg/d; and naproxen, 500 mg, twice a day as needed for pain. She does not take opioids for pain control because she had a poor response when used in the past. Ms. C denies muscle pain or tenderness but describes pain in nonspecific areas of her arm, shoulder, neck, and chest. Ms. C reports poor quality of sleep and early morning awakenings, which she attributes to her unmanaged pain. Her last appointment with a psychiatrist was “many, many months ago.”

A reciprocal relationship exists between depression and pain. A 2-year, population-based, prospective, observational study of 3,654 patients showed that pain at baseline was an independent predictor of depression and a depression diagnosis was a predictor of developing pain within 2 years.1 Patients with MDD might complain of physical symptoms, such as constipation, generalized aches, frequent headache, and fatigue, many of which overlap with chronic pain disorders. Therefore, a thorough symptom assessment and history is vital for an accurate diagnosis. To decrease polypharmacy and pill burden, optimal treatment should employ agents that treat both conditions.

Using antidepressants to treat pain disorders

Several antidepressants have been studied for managing pain disorders including:

- fibromyalgia

- diabetic neuropathy

- neuropathic pain

- postherpetic neuralgia

- migraine prophylaxis

- chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Antidepressants that treat both depression and chronic neuropathic pain include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (Table).2-12 Notably, most antidepressants studied for pain management are used off-label; duloxetine is the only medication with an FDA indication for MDD and pain disorders.

The hypothesized mechanism of action is dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, based on the monoamine hypothesis of depression and pain signaling dysfunction in neuropathic pain. Antidepressants, such as TCAs and SNRIs, address pain by increasing the synaptic concentration of norepinephrine and/or serotonin in the dorsal horn, thereby inhibiting the release of excitatory neurotransmitters and blunting pain pathways.13

TCAs used to treat comorbid depression and pain conditions include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, and desipramine.14 TCAs are cost-effective medications for managing neuropathy and headache; however, the dosages used for pain tend to be lower than those typically used for depression.

TCAs are not commonly prescribed for depression because of their side-effect profile and poor tolerability. TCAs are contraindicated in patients with cardiac conduction abnormalities, epilepsy, and narrow-angle glaucoma. Common adverse effects include dry mouth, sweating, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, sedation, weight gain, urinary retention, and constipation. These adverse effects limit their use and have organizations, such as the American Geriatric Society, to caution against their use in geriatric patients.

SNRIs that have been studied for pain disorders include venlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran.2 Of note, milnacipran is not FDA-approved for MDD, but its L-enantiomer, levomilnacipran, is. Unlike duloxetine and venlafaxine, both milnacipran and levomilnacipran are not available as a generic formulation, therefore they have a higher patient cost. The SNRI dosages used for pain management tend to be similar to those used for MDD, indicating that the target dosage may be effective for both depressive and pain symptoms.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Compared with data available supporting the use of TCAs and SNRIs for pain management, the data for SSRI are sparse. Studies have evaluated fluoxetine, paroxetine, and citalopram for pain, with the most promising data supporting fluoxetine.2 Fluoxetine, 10 to 80 mg/d, has been evaluated in randomized, placebo-controlled trials for pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (n = 3), painful diabetic neuropathy (n = 1), and facial pain (n = 1). Fluoxetine was more effective than placebo at controlling pain in 2 fibromyalgia studies (dosage range, 10 to 80 mg/d) and 1 facial pain study (dosage, 20 mg/d).2

CASE CONTINUED

When evaluating potential treatment options, it is noted that Ms. C is prescribed sertraline, 200 mg/d, but has been taking a lower dosage. Ms. C states that she has been taking sertraline, 100 mg every morning, for months, and noticed some minor initial improvements in mood, but still has days when she don’t feel like doing anything. She fills out a depression rating scale classifying her current depression as moderately severe. Today she rates her pain as 7 out of 10. Suboptimal control of her depression may require a dosage increase; however, perhaps a change in therapy is warranted. It may be prudent to switch Ms. C to an SNRI, such as duloxetine, an agent that can address her depression and provide additional benefits of pain control.

Switching from a SSRI to duloxetine has been shown to be effective when targeting pain symptoms in patients with comorbid MDD. In addition, improvements in pain scores have been seen after a switch to duloxetine in patients with depression with nonresponse or partial response to a SSRI.15

Studies support the decision to change Ms. C’s medication from sertraline to duloxetine, despite an inadequate therapeutic trial of the SSRI.

Using pain medication to treat depression

Conversely, the use of pain medications to treat depression also has been studied. The most notable data supports the use of ketamine, an anesthetic. IV ketamine is well documented for treating pain and, in recent years, has been evaluated for MDD in several small studies. Results show that IV ketamine, 0.5 mg/kg, produced a rapid response in depressed patients.16 For pain conditions studies support the use of ketamine as an IV push, continuous infusion, intermittent infusion, as well as oral administration, for many conditions, including acute and postoperative pain, chronic regional pain, and neuropathic pain. However, there is little evidence evaluating ketamine’s effect on both pain scores and depression symptoms in patients such as Ms. C.

1. Chou KL. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression in older adults: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):115-123.

2. Lee YC, Chen PP. A review of SSRIs and SNRIs in neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(17):2813-2825.

3. Arnold LM, Hess EV, Hudson JI, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):191-197.

4. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lily and Company; 2015.

5. Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al; American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine; American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1758-1765.

6. McQuay HJ, Carroll D, Glynn CJ. Low dose amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Anaesthesia. 1992;47(8):646-652.

7. Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al; European Federation of Neurological Societies. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine—revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):968-981.

8. Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Williams RA, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of nortriptyline for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1998;76(3):287-296.

9. Haviv Y, Rettman A, Aframian D, et al. Myofascial pain: an open study on the pharmacotherapeutic response to stepped treatment with tricyclic antidepressants and gabapentin. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2015;29(2):144-151.

10. Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM. Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2014;7:99-115.

11. Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA, Pappagallo M, et al. Opioids versus antidepressants in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2002;59(7):1015-1021.

12. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

13. Argoff C. Mechanisms of pain transmission and pharmacologic management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):2019-2031.

14. Haanpää ML, Gourlay GK, Kent JL, et al. Treatment considerations for patients with neuropathic pain and other medical comorbidities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(suppl 3):S15-S25.

15. Perahia DGS, Quail D, Desaiah D, et al. Switching to duloxetine in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor non- and partial-responders: effects on painful physical symptoms of depression. J Psychiatric Res. 2009;43(5):512-518.

16. Caddy C, Amit BH, McCloud TL, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub2.

1. Chou KL. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression in older adults: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):115-123.

2. Lee YC, Chen PP. A review of SSRIs and SNRIs in neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(17):2813-2825.

3. Arnold LM, Hess EV, Hudson JI, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):191-197.

4. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lily and Company; 2015.

5. Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al; American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine; American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1758-1765.

6. McQuay HJ, Carroll D, Glynn CJ. Low dose amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Anaesthesia. 1992;47(8):646-652.

7. Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al; European Federation of Neurological Societies. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine—revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):968-981.

8. Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Williams RA, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of nortriptyline for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1998;76(3):287-296.

9. Haviv Y, Rettman A, Aframian D, et al. Myofascial pain: an open study on the pharmacotherapeutic response to stepped treatment with tricyclic antidepressants and gabapentin. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2015;29(2):144-151.

10. Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM. Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2014;7:99-115.

11. Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA, Pappagallo M, et al. Opioids versus antidepressants in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2002;59(7):1015-1021.

12. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

13. Argoff C. Mechanisms of pain transmission and pharmacologic management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):2019-2031.

14. Haanpää ML, Gourlay GK, Kent JL, et al. Treatment considerations for patients with neuropathic pain and other medical comorbidities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(suppl 3):S15-S25.

15. Perahia DGS, Quail D, Desaiah D, et al. Switching to duloxetine in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor non- and partial-responders: effects on painful physical symptoms of depression. J Psychiatric Res. 2009;43(5):512-518.

16. Caddy C, Amit BH, McCloud TL, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub2.