User login

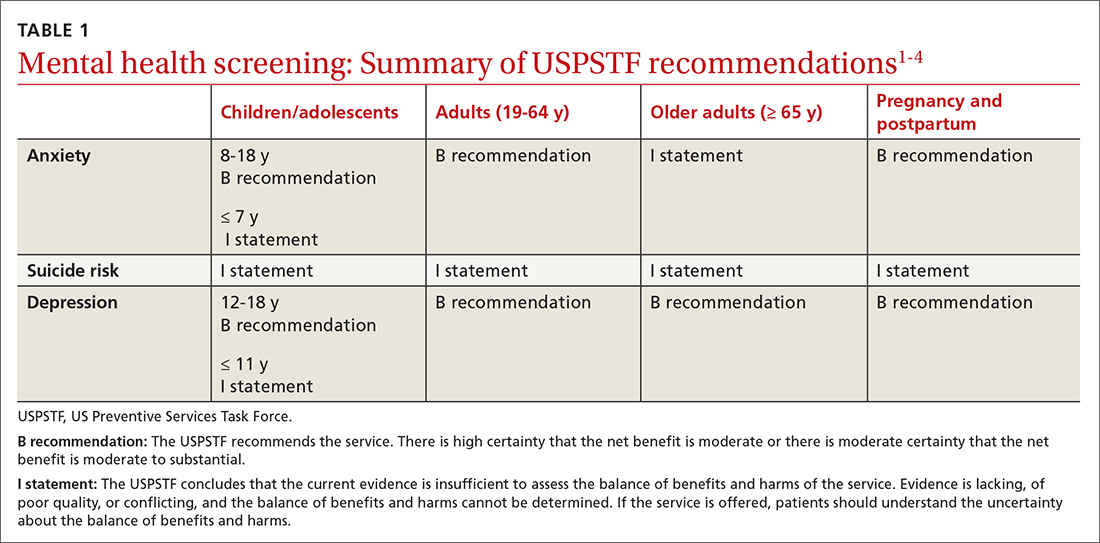

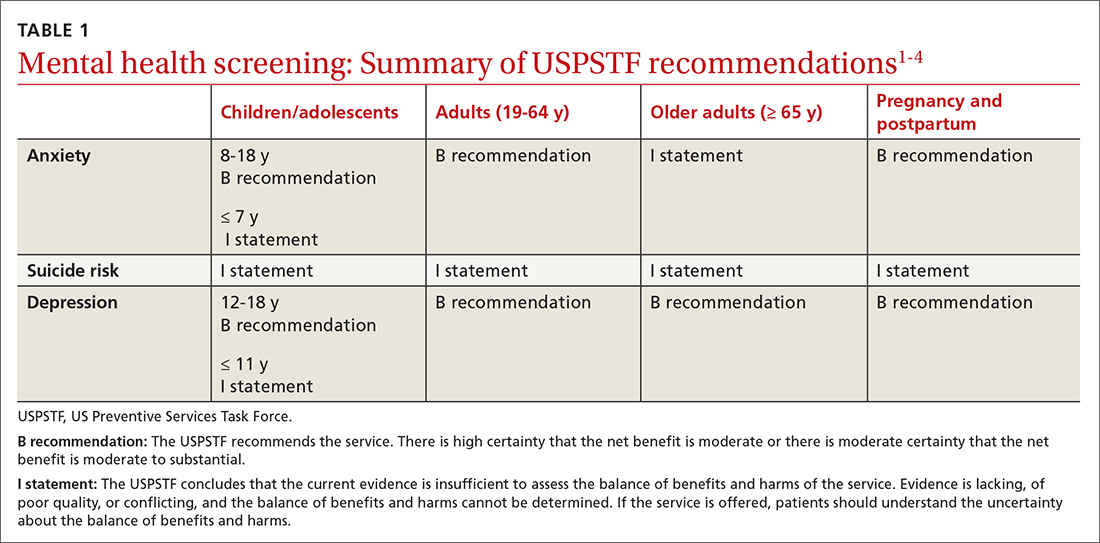

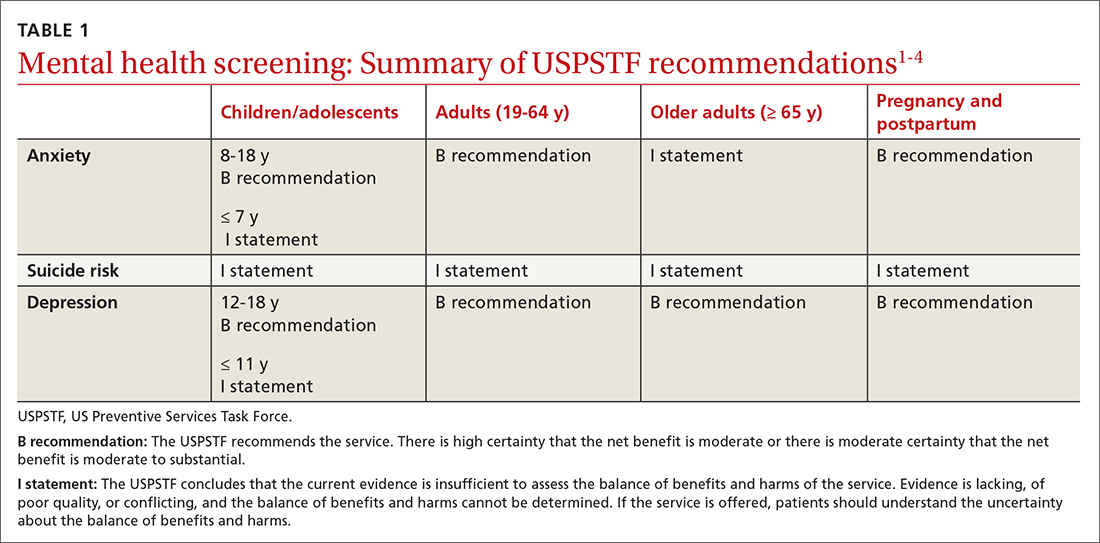

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

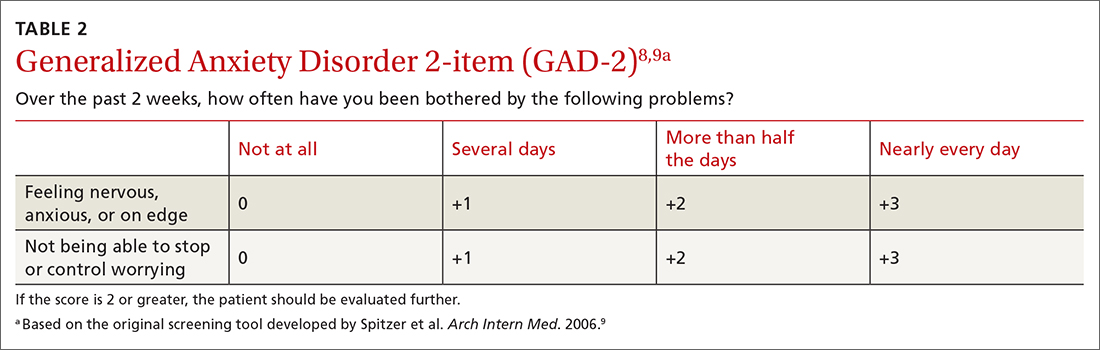

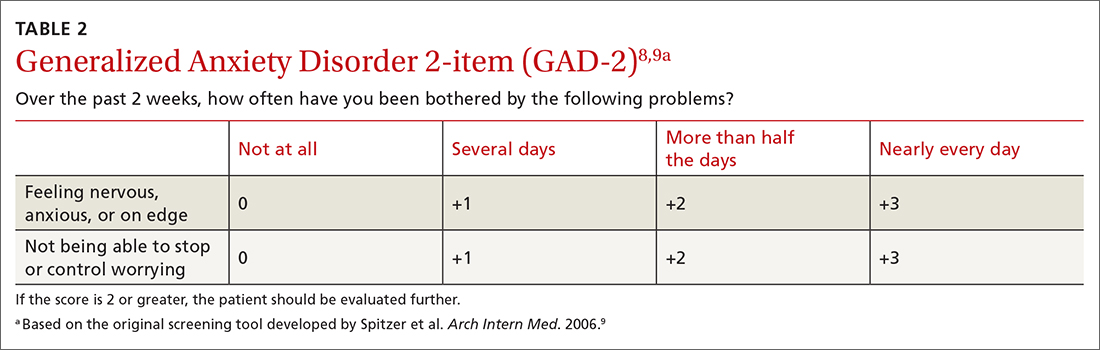

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

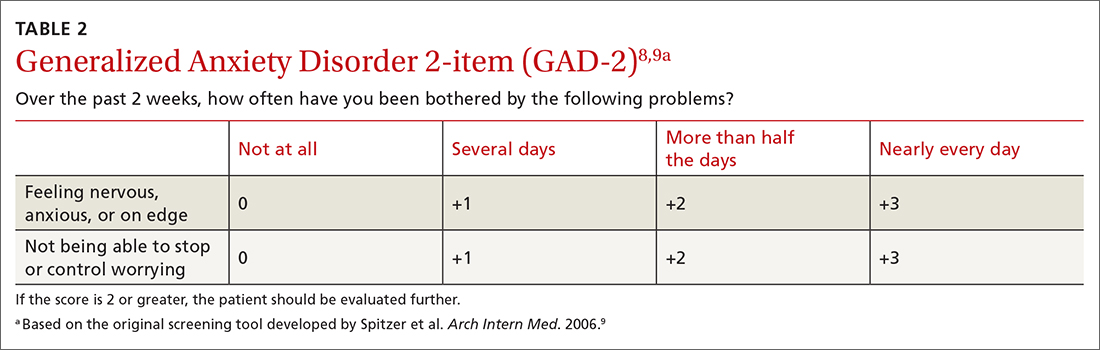

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

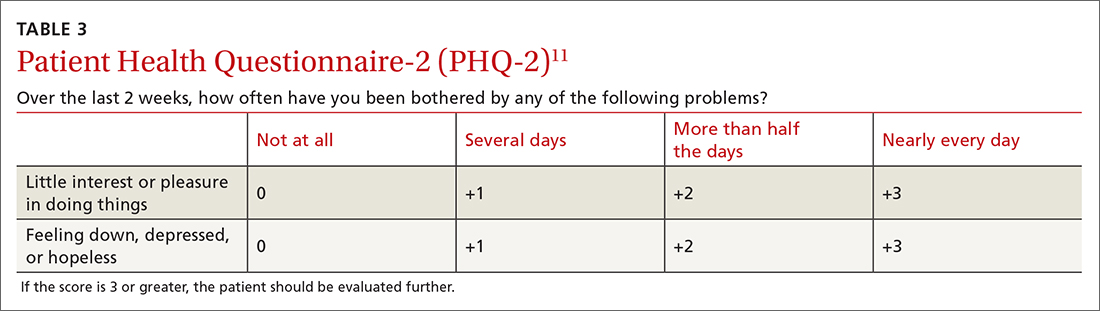

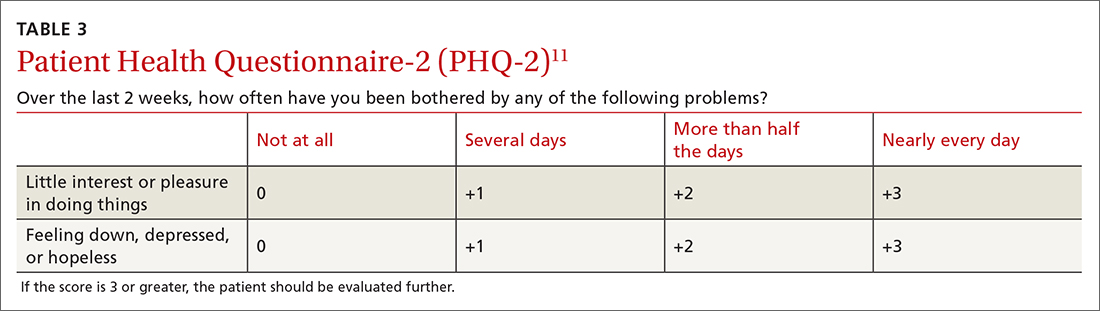

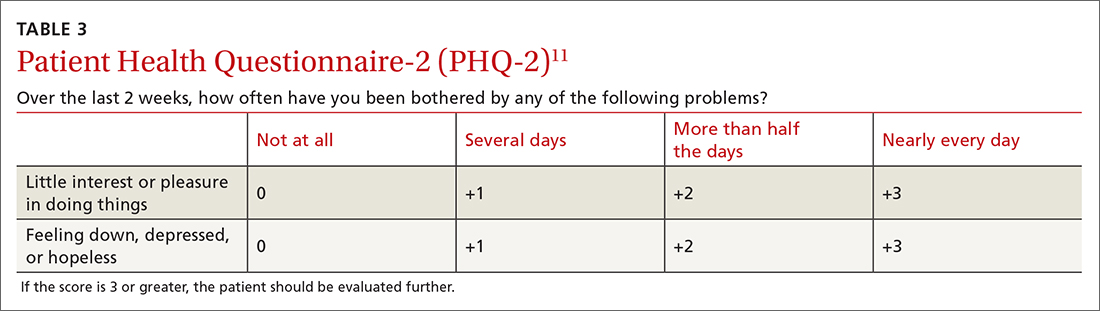

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310