User login

A 45-year-old woman noticed some redness and scaling around her right nipple. She applied peroxide and OTC antibiotic ointment for approximately seven months with mixed results. She sought medical attention when pain developed in the breast, along with some bloody discharge from the nipple (see Figure 1). Around that time, she also noticed three small nodules in the upper outer portion of the breast.

A mammogram and ultrasound revealed a 1.7 × 2.0–cm spiculated mass in the axillary tail, as well as two smaller breast lesions. A PET/CT scan ordered subsequently revealed intense uptake in the periareolar region and a suspicious axillary node. By then, the biopsy results had confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma, later determined to be Paget’s disease of the breast (PDB).

The patient’s previous medical history was significant for cystic breasts (never biopsied), chronic back pain, anxiety, and obesity. She was perimenopausal with irregular periods, the last one about 10 months ago. Her obstetric history included two pregnancies resulting in live births and no history of abortion; her menarche occurred at age 14 and her first pregnancy at 27. Family history was significant for leukemia in her maternal grandmother and niece. She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. She lived at home with her husband and two daughters, who were all very supportive.

The patient elected to undergo a right modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and prophylactic left total mastectomy. MRM was performed on the right breast because sentinel lymph node identification was unsuccessful. This may have been due to involvement of the right subareolar plexus. Five of eight lymph nodes later tested positive for malignancy. The surgery was completed by placement of bilateral tissue expanders for eventual breast reconstruction.

Chemotherapy was started six weeks after surgery and included 15 weeks (five cycles) of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab (a combination known as TCH), followed by 51 weeks (17 cycles) of trastuzumab, along with daily tamoxifen. The TCH regimen was followed by four weekly cycles of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Adverse effects of treatment have included chest wall dermatitis, right upper extremity lymphedema, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia, and fatigue.

Discussion

Nearly 150 years ago, James Paget recognized a connection between skin changes around the nipple and deeper lesions in the breast.1 The disease that Paget identified is defined as the presence of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma cells (ie, Paget’s cells) within the epidermis of the nipple, with or without an underlying carcinoma.

An underlying breast cancer is present 85% to 95% of the time but is palpable in only approximately 50% of cases (see Figure 2). However, 25% of the time there is neither a palpable mass nor a mammographic abnormality. In these cases particularly, timely diagnosis depends on recognition of suspicious nipple changes, followed by a prompt and thorough diagnostic workup. Unfortunately, the accurate diagnosis of Paget’s disease still takes an average of several months.2

Paget’s disease is rare; it represents only 1% to 3% of new cases of female breast cancer, or about 2,250 cases a year.2-4 (The number of Paget’s disease cases per year was calculated by the author, based on the reported incidence of all breast cancers.) It is even more rare among men. For both genders, the peak age for this disease is between 50 and 60.2

Paget’s disease is an important entity for primary care PAs and NPs because it presents an opportunity to make a timely and life-changing diagnosis, and because it provides an elegant model for understanding current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to breast cancer.

Clinical Presentation and Pathophysiology

The hallmark of PDB is scaly, vesicular, or ulcerated changes that begin in the nipple and spread to the areola. These changes are most often unilateral and may occur with pruritus, burning pain, and/or oozing from the nipple.5 This presentation is often mistaken for common skin conditions, such as eczema. Like eczema, changes in PDB may improve spontaneously and fluctuate over time, which is confusing for both the patient and clinician. A clinical pearl is that eczema is more likely to spread from the areola to the nipple, and will usually respond to topical corticosteroids. By contrast, changes in PDB tend to spread from the nipple to the areola, and corticosteroids do not provide a sustained response. Of note, Paget’s lesions may heal spontaneously even as the underlying malignancy progresses.6

PDB is unique because the underlying lesion and skin changes are not just coincidental. The cutaneous changes and the malignancy that lies beneath have a causal, not merely co-occurring, relationship. Paget himself believed that the nipple changes were both a precursor, and a promoter, of the underlying cancer.1 This transformation theory states that normal nipple epidermis turns into Paget’s cells spontaneously, before there is any underlying disease. This theory is supported by the fact that, occasionally (though rarely), no underlying breast cancer is ever found. Also, the concomitant tumor may be some distance (> 2 cm) from the nipple-areolar complex (NAC), suggesting a synchronous but causally unrelated lesion.6-8

Modern immunochemistry has turned PDB inside out. Today, PDB is believed to begin within the breast and then to spread “upward” to the NAC, called the epidermotrophic theory. This theory is supported by the fact that Paget’s cells share several molecular markers with their respective parenchymal tumors. Some researchers now propose that there is a single Paget’s progenitor cell with a motility factor that allows it to traverse the ductal system, resulting in nipple and skin changes that have come to be recognized as PDB.6-8

The invasive cancers that are associated with PDB are most likely to be both estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–negative and of a high histologic grade.3,7 Estrogen- and progesterone-sensitive tumors respond to hormonal manipulation therapy. Tumors that are receptor-negative and that have a more aggressive grade are more difficult to treat.

Differential Diagnosis

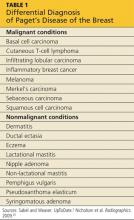

PDB may be confused with the early stages of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), an aggressive malignant disease (see Table 1). Both conditions may present with erythema and skin thickening and may be mistaken for mastitis. However, IBC spreads rapidly through the entire breast, and clinical features may include tenderness, a feeling of heat or heaviness, breast enlargement, and significant lymphadenopathy. Current recommendations call for a biopsy of any area of breast inflammation that does not respond to antibiotics within seven days.9

PDB is not the only cutaneous manifestation of breast cancer. Others include carcinoma erysipeloides (inflammatory changes that resemble cellulitis), carcinoma telangiectaticum (vascularized plaques), and/or inflammatory papules or nodules appearing on the breast, back, neck, or scalp. Each of these non–Paget’s conditions involves lymphatic (versus ductal) spread and signifies advanced malignancy.10

Diagnosis and Staging

After biopsy of the nipple lesion(s), diagnosis proceeds to the assessment of the breast itself and ultimately to cancer staging. PDB may occur (in order of incidence):

• In conjunction with an invasive cancer

• With underlying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

• Without any underlying disease.7

Mammography is used to determine the extent and location of the underlying lesion(s), which is more likely to be peripheral and/or multicentric. However, in some cases, there are no mammographic changes, which is now recognized as an indication for performing a breast MRI.11 Once the lesion is located, direct or image-guided biopsy confirms whether it is invasive cancer or DCIS. Palpable masses that occur with PDB are usually invasive and signal advanced disease.2,6,12,13 Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), which is usually performed at the time of surgery, plays a critical role in cancer staging and treatment planning. SLNB reliably diagnoses axillary metastasis in approximately 98% of patients.14

Like other breast cancers, PDB is also categorized by the expression of molecular markers, including HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). Cancer cells in which HER2 gene is overexpressed tend to proliferate more rapidly than others. HER-status can also provide a clue as to which chemotherapy agents are likely to be most effective.2

Treatment and Management

The primary treatment for breast cancer is surgery, which serves both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. To be effective, surgical treatment of PDB requires excision of the NAC, also called central lumpectomy. This may be sufficient treatment in those rare cases in which the disease is confined to the NAC.11,12

For underlying tumors, partial mastectomy is an option when the tumor is small (< 2 cm) and located close enough to the NAC to achieve negative margins, while leaving a cosmetically acceptable breast. Partial mastectomy is usually followed by whole breast irradiation. A few centers offer intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT)—performed before the surgeon closes the incision—for patients who wish to avoid or limit the duration of postoperative radiation treatment.15-17

Complete mastectomy (including excision of the NAC) should be considered when:

• The distance between the NAC and the underlying tumor is significant

• Multicentric disease and/or diffuse calcifications exist

• Achieving negative margins would remove too much tissue to leave a cosmetically acceptable breast.

Evaluation of the axillary nodes is the same in PDB as with other breast cancers. Patients with disease localized to the NAC and no underlying carcinoma may choose to forego lymph node biopsy. The same is true for patients who have PDB with a single underlying DCIS. However, lymph node biopsy is always recommended in cases of multicentric DCIS or invasive disease, or if a mastectomy is planned.18,19

Sentinel node biopsy results determine whether the mastectomy should be simple (excision of the breast alone) or modified radical (breast and axillary nodes). Today, complete radical mastectomy (excision of the breast, axillary nodes, and pectoral muscle) is reserved for cases in which disease invades the chest wall.18,19

The use of adjuvant (postoperative) therapy in patients with DCIS (whether or not related to PDB) is still debated. For patients with invasive cancers, both radiation therapy and chemotherapy are usually indicated. The decision to use neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemotherapy is made on a case-by-case basis. All decisions are based on the nature of the underlying cancer, regardless of whether the diagnosis is PDB.

Because PDB is categorized as invasive in at least 85% of cases, and because all invasive breast cancers carry about twice the risk for newly diagnosed contralateral disease, systematic follow-up is extremely important for patients with PDB. A clinical exam and updated history should be performed every four to six months during the first two years and at least annually after that. Screening recommendations, including a yearly mammogram, remain the same for asymptomatic patients. Patients with new or recurring symptoms—because they are at high risk for cancer recurrence—or who are undergoing treatment may have additional testing, including assessing for tumor markers, ultrasound, or MRI.2

PDB is treated with the same chemotherapy regimens as other breast cancers. In the early stages, chemotherapy reduces the risk for recurrence. In advanced breast cancer, the goal of chemotherapy is to reduce tumor size and achieve local control.

Prognosis

Patients with negative lymph node biopsy results have survival rates of 85% and 79% at five and 10 years, respectively. Patients with positive node results face survival rates of 32% at five years and 28% at 10 years. As with other cancers, anything that contributes to disease progression (including delayed diagnosis or treatment) decreases the patient’s survival rate.2,3 The overall prognosis for PDB is based on the nature of the underlying breast cancer, including its stage and other predictive factors—not on the fact that it is PDB.

Patient Outcome

Nearing the end of her treatment with trastuzumab, the patient became concerned about new-onset vaginal and left pelvic pain, along with some lower back discomfort. She mentioned these symptoms to her oncologist immediately. A transvaginal ultrasound could not rule out an ovarian neoplasm.

The patient elected to undergo total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO). This option allowed for removal of a mass discovered during the procedure, minimized the risk for subsequent endometrial cancer, and reduced the chance of recurrence of the patient’s estrogen/progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer. The mass itself turned out to be a benign pedunculated fibroid tumor.

The patient was relieved and continues to recover well. A follow-up PET/CT scan is scheduled for three months from now.

Conclusion

PDB is a complex disease that challenges our current understanding of breast cancer and its diagnosis and treatment. It depends uniquely upon ductal (versus blood or lymphatic) spread. Little did Paget and his contemporaries realize they had opened up such a porthole into modern histology. Nor did they appreciate the fact that they had identified an insidious breast cancer that declares itself through the skin.

Today, it is understood that by the time nipple changes of PDB appear, an underlying breast cancer most likely exists. In at least 25% of cases, there is neither a palpable mass nor a positive mammogram finding. For this reason, clinicians must maintain a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for biopsy when there are skin changes at the nipple. This is especially true because the underlying lesions are more likely to be invasive cancers.

Surgical treatment will often mean complete mastectomy, whether simple, modified radical, or radical. This choice will be driven by the extent and location of the underlying disease. There is a role for partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy in those rare cases in which PDB is confined to the NAC with no underlying tumor. Partial mastectomy is also a consideration when the underlying tumor is small and/or located close to the NAC. Patients with PDB may consider whole-breast or NAC reconstruction once radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy are completed.

PDB remains a poignant reminder for all clinicians of the importance of a thorough clinical exam and a well-focused history in all patients at risk for breast cancer. Moreover, it is an enduring example of the fact that common symptoms sometimes do signify something uncommon and potentially life- changing.

References

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. In: Paget S, ed. Selected Essays and Addresses by Sir James Paget. London: Longmans, Green and Co.; 1902:145-148.

2. Sabel MS, Weaver DL. Paget disease of the breast. In: UpToDate. Chagpar AE, Hayes DF, Pierce LJ, eds. www.uptodate.com/contents/paget-disease-of-the-breast. Updated November 27, 2012. Accessed September 9, 2013.

3. Ortiz-Pagan S, Cunto-Amesty G, Narayan S. Effect of Paget’s disease on survival in breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2001;146:1267-1270.

4. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2012. www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2012. Accessed September 9, 2013.

5. Ashikari R, Park K, Huvos AG, Urban JA. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer. 1970;3:680-685.

6. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard K, Sarr MG, Farley DR. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer Treatment Rev. 2001;27:9-18.

7. Chen C-Y, Sun L-M, Anderson BO. Paget disease of the breast: changing patterns of incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment in the U.S. Cancer. 2006;107:1448-1458.

8. Paone JF, Baker R. Pathogenesis and treatment of Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer. 1981;48:825-829.

9. Nelson JA, Patel D, Mancuso P. Inflammatory breast cancer. ADVANCE for NPs and PAs. 2011;2(10):25-28.

10. Ngan V. Skin metastasis. DermNet NZ. New Zealand Dermatological Society. http://dermnetnz.org/lesions/metastasis.html. Accessed September 9, 2013.

11. Amano G, Yajima M, Moroboshi Y, et al. MRI accurately depicts underlying DCIS in a patient with Paget’s disease of the breast without palpable mass and mammography findings. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:149-153.

12. Burrell HC, Evans AJ. Radiological assessment of the breast: what the surgical oncologist needs to know. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:689-691.

13. Muttarak M, Siriya B, Kongmebhol P. Paget’s disease of the breast: clinical, imaging and pathologic findings: a review of 16 patients. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2001;7:e16, 1-7.

14. Laronga C, Hasson D, Hoover S, et al. Paget’s disease in the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:481-483.

15. Pezzi CM, Kukora JS, Audet IM. Breast conservation surgery using nipple-areolar resection for central breast cancers. Arch Surg. 2004;139:32-37.

16. Polgar C, Zsolt O, Tibor K, Janos F. Breast-conserving therapy for Paget disease of the nipple. Cancer. 2002;94:1904-1905.

17. Marshall JK, Griffith KA, Haffty BG, Solin LJ. Conservative management of Paget disease of the breast with radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2142-2149.

18. Vasquez B, Rousseau D, Hurd TC. Surgical management of breast cancer. Sem Oncol. 2007;34:234-240.

19. Mamounas EP. Continuing evolution in breast cancer surgical management. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1603-1606.

20. Nicholson BT, Harvey JA, Cohen MA. Nipple-areolar complex: normal anatomy and benign and malignant processes. Radiographics. 2009;29:509-523.

A 45-year-old woman noticed some redness and scaling around her right nipple. She applied peroxide and OTC antibiotic ointment for approximately seven months with mixed results. She sought medical attention when pain developed in the breast, along with some bloody discharge from the nipple (see Figure 1). Around that time, she also noticed three small nodules in the upper outer portion of the breast.

A mammogram and ultrasound revealed a 1.7 × 2.0–cm spiculated mass in the axillary tail, as well as two smaller breast lesions. A PET/CT scan ordered subsequently revealed intense uptake in the periareolar region and a suspicious axillary node. By then, the biopsy results had confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma, later determined to be Paget’s disease of the breast (PDB).

The patient’s previous medical history was significant for cystic breasts (never biopsied), chronic back pain, anxiety, and obesity. She was perimenopausal with irregular periods, the last one about 10 months ago. Her obstetric history included two pregnancies resulting in live births and no history of abortion; her menarche occurred at age 14 and her first pregnancy at 27. Family history was significant for leukemia in her maternal grandmother and niece. She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. She lived at home with her husband and two daughters, who were all very supportive.

The patient elected to undergo a right modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and prophylactic left total mastectomy. MRM was performed on the right breast because sentinel lymph node identification was unsuccessful. This may have been due to involvement of the right subareolar plexus. Five of eight lymph nodes later tested positive for malignancy. The surgery was completed by placement of bilateral tissue expanders for eventual breast reconstruction.

Chemotherapy was started six weeks after surgery and included 15 weeks (five cycles) of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab (a combination known as TCH), followed by 51 weeks (17 cycles) of trastuzumab, along with daily tamoxifen. The TCH regimen was followed by four weekly cycles of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Adverse effects of treatment have included chest wall dermatitis, right upper extremity lymphedema, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia, and fatigue.

Discussion

Nearly 150 years ago, James Paget recognized a connection between skin changes around the nipple and deeper lesions in the breast.1 The disease that Paget identified is defined as the presence of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma cells (ie, Paget’s cells) within the epidermis of the nipple, with or without an underlying carcinoma.

An underlying breast cancer is present 85% to 95% of the time but is palpable in only approximately 50% of cases (see Figure 2). However, 25% of the time there is neither a palpable mass nor a mammographic abnormality. In these cases particularly, timely diagnosis depends on recognition of suspicious nipple changes, followed by a prompt and thorough diagnostic workup. Unfortunately, the accurate diagnosis of Paget’s disease still takes an average of several months.2

Paget’s disease is rare; it represents only 1% to 3% of new cases of female breast cancer, or about 2,250 cases a year.2-4 (The number of Paget’s disease cases per year was calculated by the author, based on the reported incidence of all breast cancers.) It is even more rare among men. For both genders, the peak age for this disease is between 50 and 60.2

Paget’s disease is an important entity for primary care PAs and NPs because it presents an opportunity to make a timely and life-changing diagnosis, and because it provides an elegant model for understanding current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to breast cancer.

Clinical Presentation and Pathophysiology

The hallmark of PDB is scaly, vesicular, or ulcerated changes that begin in the nipple and spread to the areola. These changes are most often unilateral and may occur with pruritus, burning pain, and/or oozing from the nipple.5 This presentation is often mistaken for common skin conditions, such as eczema. Like eczema, changes in PDB may improve spontaneously and fluctuate over time, which is confusing for both the patient and clinician. A clinical pearl is that eczema is more likely to spread from the areola to the nipple, and will usually respond to topical corticosteroids. By contrast, changes in PDB tend to spread from the nipple to the areola, and corticosteroids do not provide a sustained response. Of note, Paget’s lesions may heal spontaneously even as the underlying malignancy progresses.6

PDB is unique because the underlying lesion and skin changes are not just coincidental. The cutaneous changes and the malignancy that lies beneath have a causal, not merely co-occurring, relationship. Paget himself believed that the nipple changes were both a precursor, and a promoter, of the underlying cancer.1 This transformation theory states that normal nipple epidermis turns into Paget’s cells spontaneously, before there is any underlying disease. This theory is supported by the fact that, occasionally (though rarely), no underlying breast cancer is ever found. Also, the concomitant tumor may be some distance (> 2 cm) from the nipple-areolar complex (NAC), suggesting a synchronous but causally unrelated lesion.6-8

Modern immunochemistry has turned PDB inside out. Today, PDB is believed to begin within the breast and then to spread “upward” to the NAC, called the epidermotrophic theory. This theory is supported by the fact that Paget’s cells share several molecular markers with their respective parenchymal tumors. Some researchers now propose that there is a single Paget’s progenitor cell with a motility factor that allows it to traverse the ductal system, resulting in nipple and skin changes that have come to be recognized as PDB.6-8

The invasive cancers that are associated with PDB are most likely to be both estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–negative and of a high histologic grade.3,7 Estrogen- and progesterone-sensitive tumors respond to hormonal manipulation therapy. Tumors that are receptor-negative and that have a more aggressive grade are more difficult to treat.

Differential Diagnosis

PDB may be confused with the early stages of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), an aggressive malignant disease (see Table 1). Both conditions may present with erythema and skin thickening and may be mistaken for mastitis. However, IBC spreads rapidly through the entire breast, and clinical features may include tenderness, a feeling of heat or heaviness, breast enlargement, and significant lymphadenopathy. Current recommendations call for a biopsy of any area of breast inflammation that does not respond to antibiotics within seven days.9

PDB is not the only cutaneous manifestation of breast cancer. Others include carcinoma erysipeloides (inflammatory changes that resemble cellulitis), carcinoma telangiectaticum (vascularized plaques), and/or inflammatory papules or nodules appearing on the breast, back, neck, or scalp. Each of these non–Paget’s conditions involves lymphatic (versus ductal) spread and signifies advanced malignancy.10

Diagnosis and Staging

After biopsy of the nipple lesion(s), diagnosis proceeds to the assessment of the breast itself and ultimately to cancer staging. PDB may occur (in order of incidence):

• In conjunction with an invasive cancer

• With underlying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

• Without any underlying disease.7

Mammography is used to determine the extent and location of the underlying lesion(s), which is more likely to be peripheral and/or multicentric. However, in some cases, there are no mammographic changes, which is now recognized as an indication for performing a breast MRI.11 Once the lesion is located, direct or image-guided biopsy confirms whether it is invasive cancer or DCIS. Palpable masses that occur with PDB are usually invasive and signal advanced disease.2,6,12,13 Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), which is usually performed at the time of surgery, plays a critical role in cancer staging and treatment planning. SLNB reliably diagnoses axillary metastasis in approximately 98% of patients.14

Like other breast cancers, PDB is also categorized by the expression of molecular markers, including HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). Cancer cells in which HER2 gene is overexpressed tend to proliferate more rapidly than others. HER-status can also provide a clue as to which chemotherapy agents are likely to be most effective.2

Treatment and Management

The primary treatment for breast cancer is surgery, which serves both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. To be effective, surgical treatment of PDB requires excision of the NAC, also called central lumpectomy. This may be sufficient treatment in those rare cases in which the disease is confined to the NAC.11,12

For underlying tumors, partial mastectomy is an option when the tumor is small (< 2 cm) and located close enough to the NAC to achieve negative margins, while leaving a cosmetically acceptable breast. Partial mastectomy is usually followed by whole breast irradiation. A few centers offer intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT)—performed before the surgeon closes the incision—for patients who wish to avoid or limit the duration of postoperative radiation treatment.15-17

Complete mastectomy (including excision of the NAC) should be considered when:

• The distance between the NAC and the underlying tumor is significant

• Multicentric disease and/or diffuse calcifications exist

• Achieving negative margins would remove too much tissue to leave a cosmetically acceptable breast.

Evaluation of the axillary nodes is the same in PDB as with other breast cancers. Patients with disease localized to the NAC and no underlying carcinoma may choose to forego lymph node biopsy. The same is true for patients who have PDB with a single underlying DCIS. However, lymph node biopsy is always recommended in cases of multicentric DCIS or invasive disease, or if a mastectomy is planned.18,19

Sentinel node biopsy results determine whether the mastectomy should be simple (excision of the breast alone) or modified radical (breast and axillary nodes). Today, complete radical mastectomy (excision of the breast, axillary nodes, and pectoral muscle) is reserved for cases in which disease invades the chest wall.18,19

The use of adjuvant (postoperative) therapy in patients with DCIS (whether or not related to PDB) is still debated. For patients with invasive cancers, both radiation therapy and chemotherapy are usually indicated. The decision to use neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemotherapy is made on a case-by-case basis. All decisions are based on the nature of the underlying cancer, regardless of whether the diagnosis is PDB.

Because PDB is categorized as invasive in at least 85% of cases, and because all invasive breast cancers carry about twice the risk for newly diagnosed contralateral disease, systematic follow-up is extremely important for patients with PDB. A clinical exam and updated history should be performed every four to six months during the first two years and at least annually after that. Screening recommendations, including a yearly mammogram, remain the same for asymptomatic patients. Patients with new or recurring symptoms—because they are at high risk for cancer recurrence—or who are undergoing treatment may have additional testing, including assessing for tumor markers, ultrasound, or MRI.2

PDB is treated with the same chemotherapy regimens as other breast cancers. In the early stages, chemotherapy reduces the risk for recurrence. In advanced breast cancer, the goal of chemotherapy is to reduce tumor size and achieve local control.

Prognosis

Patients with negative lymph node biopsy results have survival rates of 85% and 79% at five and 10 years, respectively. Patients with positive node results face survival rates of 32% at five years and 28% at 10 years. As with other cancers, anything that contributes to disease progression (including delayed diagnosis or treatment) decreases the patient’s survival rate.2,3 The overall prognosis for PDB is based on the nature of the underlying breast cancer, including its stage and other predictive factors—not on the fact that it is PDB.

Patient Outcome

Nearing the end of her treatment with trastuzumab, the patient became concerned about new-onset vaginal and left pelvic pain, along with some lower back discomfort. She mentioned these symptoms to her oncologist immediately. A transvaginal ultrasound could not rule out an ovarian neoplasm.

The patient elected to undergo total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO). This option allowed for removal of a mass discovered during the procedure, minimized the risk for subsequent endometrial cancer, and reduced the chance of recurrence of the patient’s estrogen/progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer. The mass itself turned out to be a benign pedunculated fibroid tumor.

The patient was relieved and continues to recover well. A follow-up PET/CT scan is scheduled for three months from now.

Conclusion

PDB is a complex disease that challenges our current understanding of breast cancer and its diagnosis and treatment. It depends uniquely upon ductal (versus blood or lymphatic) spread. Little did Paget and his contemporaries realize they had opened up such a porthole into modern histology. Nor did they appreciate the fact that they had identified an insidious breast cancer that declares itself through the skin.

Today, it is understood that by the time nipple changes of PDB appear, an underlying breast cancer most likely exists. In at least 25% of cases, there is neither a palpable mass nor a positive mammogram finding. For this reason, clinicians must maintain a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for biopsy when there are skin changes at the nipple. This is especially true because the underlying lesions are more likely to be invasive cancers.

Surgical treatment will often mean complete mastectomy, whether simple, modified radical, or radical. This choice will be driven by the extent and location of the underlying disease. There is a role for partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy in those rare cases in which PDB is confined to the NAC with no underlying tumor. Partial mastectomy is also a consideration when the underlying tumor is small and/or located close to the NAC. Patients with PDB may consider whole-breast or NAC reconstruction once radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy are completed.

PDB remains a poignant reminder for all clinicians of the importance of a thorough clinical exam and a well-focused history in all patients at risk for breast cancer. Moreover, it is an enduring example of the fact that common symptoms sometimes do signify something uncommon and potentially life- changing.

References

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. In: Paget S, ed. Selected Essays and Addresses by Sir James Paget. London: Longmans, Green and Co.; 1902:145-148.

2. Sabel MS, Weaver DL. Paget disease of the breast. In: UpToDate. Chagpar AE, Hayes DF, Pierce LJ, eds. www.uptodate.com/contents/paget-disease-of-the-breast. Updated November 27, 2012. Accessed September 9, 2013.

3. Ortiz-Pagan S, Cunto-Amesty G, Narayan S. Effect of Paget’s disease on survival in breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2001;146:1267-1270.

4. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2012. www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2012. Accessed September 9, 2013.

5. Ashikari R, Park K, Huvos AG, Urban JA. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer. 1970;3:680-685.

6. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard K, Sarr MG, Farley DR. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer Treatment Rev. 2001;27:9-18.

7. Chen C-Y, Sun L-M, Anderson BO. Paget disease of the breast: changing patterns of incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment in the U.S. Cancer. 2006;107:1448-1458.

8. Paone JF, Baker R. Pathogenesis and treatment of Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer. 1981;48:825-829.

9. Nelson JA, Patel D, Mancuso P. Inflammatory breast cancer. ADVANCE for NPs and PAs. 2011;2(10):25-28.

10. Ngan V. Skin metastasis. DermNet NZ. New Zealand Dermatological Society. http://dermnetnz.org/lesions/metastasis.html. Accessed September 9, 2013.

11. Amano G, Yajima M, Moroboshi Y, et al. MRI accurately depicts underlying DCIS in a patient with Paget’s disease of the breast without palpable mass and mammography findings. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:149-153.

12. Burrell HC, Evans AJ. Radiological assessment of the breast: what the surgical oncologist needs to know. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:689-691.

13. Muttarak M, Siriya B, Kongmebhol P. Paget’s disease of the breast: clinical, imaging and pathologic findings: a review of 16 patients. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2001;7:e16, 1-7.

14. Laronga C, Hasson D, Hoover S, et al. Paget’s disease in the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:481-483.

15. Pezzi CM, Kukora JS, Audet IM. Breast conservation surgery using nipple-areolar resection for central breast cancers. Arch Surg. 2004;139:32-37.

16. Polgar C, Zsolt O, Tibor K, Janos F. Breast-conserving therapy for Paget disease of the nipple. Cancer. 2002;94:1904-1905.

17. Marshall JK, Griffith KA, Haffty BG, Solin LJ. Conservative management of Paget disease of the breast with radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2142-2149.

18. Vasquez B, Rousseau D, Hurd TC. Surgical management of breast cancer. Sem Oncol. 2007;34:234-240.

19. Mamounas EP. Continuing evolution in breast cancer surgical management. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1603-1606.

20. Nicholson BT, Harvey JA, Cohen MA. Nipple-areolar complex: normal anatomy and benign and malignant processes. Radiographics. 2009;29:509-523.

A 45-year-old woman noticed some redness and scaling around her right nipple. She applied peroxide and OTC antibiotic ointment for approximately seven months with mixed results. She sought medical attention when pain developed in the breast, along with some bloody discharge from the nipple (see Figure 1). Around that time, she also noticed three small nodules in the upper outer portion of the breast.

A mammogram and ultrasound revealed a 1.7 × 2.0–cm spiculated mass in the axillary tail, as well as two smaller breast lesions. A PET/CT scan ordered subsequently revealed intense uptake in the periareolar region and a suspicious axillary node. By then, the biopsy results had confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma, later determined to be Paget’s disease of the breast (PDB).

The patient’s previous medical history was significant for cystic breasts (never biopsied), chronic back pain, anxiety, and obesity. She was perimenopausal with irregular periods, the last one about 10 months ago. Her obstetric history included two pregnancies resulting in live births and no history of abortion; her menarche occurred at age 14 and her first pregnancy at 27. Family history was significant for leukemia in her maternal grandmother and niece. She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. She lived at home with her husband and two daughters, who were all very supportive.

The patient elected to undergo a right modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and prophylactic left total mastectomy. MRM was performed on the right breast because sentinel lymph node identification was unsuccessful. This may have been due to involvement of the right subareolar plexus. Five of eight lymph nodes later tested positive for malignancy. The surgery was completed by placement of bilateral tissue expanders for eventual breast reconstruction.

Chemotherapy was started six weeks after surgery and included 15 weeks (five cycles) of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab (a combination known as TCH), followed by 51 weeks (17 cycles) of trastuzumab, along with daily tamoxifen. The TCH regimen was followed by four weekly cycles of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Adverse effects of treatment have included chest wall dermatitis, right upper extremity lymphedema, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia, and fatigue.

Discussion

Nearly 150 years ago, James Paget recognized a connection between skin changes around the nipple and deeper lesions in the breast.1 The disease that Paget identified is defined as the presence of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma cells (ie, Paget’s cells) within the epidermis of the nipple, with or without an underlying carcinoma.

An underlying breast cancer is present 85% to 95% of the time but is palpable in only approximately 50% of cases (see Figure 2). However, 25% of the time there is neither a palpable mass nor a mammographic abnormality. In these cases particularly, timely diagnosis depends on recognition of suspicious nipple changes, followed by a prompt and thorough diagnostic workup. Unfortunately, the accurate diagnosis of Paget’s disease still takes an average of several months.2

Paget’s disease is rare; it represents only 1% to 3% of new cases of female breast cancer, or about 2,250 cases a year.2-4 (The number of Paget’s disease cases per year was calculated by the author, based on the reported incidence of all breast cancers.) It is even more rare among men. For both genders, the peak age for this disease is between 50 and 60.2

Paget’s disease is an important entity for primary care PAs and NPs because it presents an opportunity to make a timely and life-changing diagnosis, and because it provides an elegant model for understanding current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to breast cancer.

Clinical Presentation and Pathophysiology

The hallmark of PDB is scaly, vesicular, or ulcerated changes that begin in the nipple and spread to the areola. These changes are most often unilateral and may occur with pruritus, burning pain, and/or oozing from the nipple.5 This presentation is often mistaken for common skin conditions, such as eczema. Like eczema, changes in PDB may improve spontaneously and fluctuate over time, which is confusing for both the patient and clinician. A clinical pearl is that eczema is more likely to spread from the areola to the nipple, and will usually respond to topical corticosteroids. By contrast, changes in PDB tend to spread from the nipple to the areola, and corticosteroids do not provide a sustained response. Of note, Paget’s lesions may heal spontaneously even as the underlying malignancy progresses.6

PDB is unique because the underlying lesion and skin changes are not just coincidental. The cutaneous changes and the malignancy that lies beneath have a causal, not merely co-occurring, relationship. Paget himself believed that the nipple changes were both a precursor, and a promoter, of the underlying cancer.1 This transformation theory states that normal nipple epidermis turns into Paget’s cells spontaneously, before there is any underlying disease. This theory is supported by the fact that, occasionally (though rarely), no underlying breast cancer is ever found. Also, the concomitant tumor may be some distance (> 2 cm) from the nipple-areolar complex (NAC), suggesting a synchronous but causally unrelated lesion.6-8

Modern immunochemistry has turned PDB inside out. Today, PDB is believed to begin within the breast and then to spread “upward” to the NAC, called the epidermotrophic theory. This theory is supported by the fact that Paget’s cells share several molecular markers with their respective parenchymal tumors. Some researchers now propose that there is a single Paget’s progenitor cell with a motility factor that allows it to traverse the ductal system, resulting in nipple and skin changes that have come to be recognized as PDB.6-8

The invasive cancers that are associated with PDB are most likely to be both estrogen- and progesterone-receptor–negative and of a high histologic grade.3,7 Estrogen- and progesterone-sensitive tumors respond to hormonal manipulation therapy. Tumors that are receptor-negative and that have a more aggressive grade are more difficult to treat.

Differential Diagnosis

PDB may be confused with the early stages of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), an aggressive malignant disease (see Table 1). Both conditions may present with erythema and skin thickening and may be mistaken for mastitis. However, IBC spreads rapidly through the entire breast, and clinical features may include tenderness, a feeling of heat or heaviness, breast enlargement, and significant lymphadenopathy. Current recommendations call for a biopsy of any area of breast inflammation that does not respond to antibiotics within seven days.9

PDB is not the only cutaneous manifestation of breast cancer. Others include carcinoma erysipeloides (inflammatory changes that resemble cellulitis), carcinoma telangiectaticum (vascularized plaques), and/or inflammatory papules or nodules appearing on the breast, back, neck, or scalp. Each of these non–Paget’s conditions involves lymphatic (versus ductal) spread and signifies advanced malignancy.10

Diagnosis and Staging

After biopsy of the nipple lesion(s), diagnosis proceeds to the assessment of the breast itself and ultimately to cancer staging. PDB may occur (in order of incidence):

• In conjunction with an invasive cancer

• With underlying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

• Without any underlying disease.7

Mammography is used to determine the extent and location of the underlying lesion(s), which is more likely to be peripheral and/or multicentric. However, in some cases, there are no mammographic changes, which is now recognized as an indication for performing a breast MRI.11 Once the lesion is located, direct or image-guided biopsy confirms whether it is invasive cancer or DCIS. Palpable masses that occur with PDB are usually invasive and signal advanced disease.2,6,12,13 Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), which is usually performed at the time of surgery, plays a critical role in cancer staging and treatment planning. SLNB reliably diagnoses axillary metastasis in approximately 98% of patients.14

Like other breast cancers, PDB is also categorized by the expression of molecular markers, including HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). Cancer cells in which HER2 gene is overexpressed tend to proliferate more rapidly than others. HER-status can also provide a clue as to which chemotherapy agents are likely to be most effective.2

Treatment and Management

The primary treatment for breast cancer is surgery, which serves both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. To be effective, surgical treatment of PDB requires excision of the NAC, also called central lumpectomy. This may be sufficient treatment in those rare cases in which the disease is confined to the NAC.11,12

For underlying tumors, partial mastectomy is an option when the tumor is small (< 2 cm) and located close enough to the NAC to achieve negative margins, while leaving a cosmetically acceptable breast. Partial mastectomy is usually followed by whole breast irradiation. A few centers offer intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT)—performed before the surgeon closes the incision—for patients who wish to avoid or limit the duration of postoperative radiation treatment.15-17

Complete mastectomy (including excision of the NAC) should be considered when:

• The distance between the NAC and the underlying tumor is significant

• Multicentric disease and/or diffuse calcifications exist

• Achieving negative margins would remove too much tissue to leave a cosmetically acceptable breast.

Evaluation of the axillary nodes is the same in PDB as with other breast cancers. Patients with disease localized to the NAC and no underlying carcinoma may choose to forego lymph node biopsy. The same is true for patients who have PDB with a single underlying DCIS. However, lymph node biopsy is always recommended in cases of multicentric DCIS or invasive disease, or if a mastectomy is planned.18,19

Sentinel node biopsy results determine whether the mastectomy should be simple (excision of the breast alone) or modified radical (breast and axillary nodes). Today, complete radical mastectomy (excision of the breast, axillary nodes, and pectoral muscle) is reserved for cases in which disease invades the chest wall.18,19

The use of adjuvant (postoperative) therapy in patients with DCIS (whether or not related to PDB) is still debated. For patients with invasive cancers, both radiation therapy and chemotherapy are usually indicated. The decision to use neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemotherapy is made on a case-by-case basis. All decisions are based on the nature of the underlying cancer, regardless of whether the diagnosis is PDB.

Because PDB is categorized as invasive in at least 85% of cases, and because all invasive breast cancers carry about twice the risk for newly diagnosed contralateral disease, systematic follow-up is extremely important for patients with PDB. A clinical exam and updated history should be performed every four to six months during the first two years and at least annually after that. Screening recommendations, including a yearly mammogram, remain the same for asymptomatic patients. Patients with new or recurring symptoms—because they are at high risk for cancer recurrence—or who are undergoing treatment may have additional testing, including assessing for tumor markers, ultrasound, or MRI.2

PDB is treated with the same chemotherapy regimens as other breast cancers. In the early stages, chemotherapy reduces the risk for recurrence. In advanced breast cancer, the goal of chemotherapy is to reduce tumor size and achieve local control.

Prognosis

Patients with negative lymph node biopsy results have survival rates of 85% and 79% at five and 10 years, respectively. Patients with positive node results face survival rates of 32% at five years and 28% at 10 years. As with other cancers, anything that contributes to disease progression (including delayed diagnosis or treatment) decreases the patient’s survival rate.2,3 The overall prognosis for PDB is based on the nature of the underlying breast cancer, including its stage and other predictive factors—not on the fact that it is PDB.

Patient Outcome

Nearing the end of her treatment with trastuzumab, the patient became concerned about new-onset vaginal and left pelvic pain, along with some lower back discomfort. She mentioned these symptoms to her oncologist immediately. A transvaginal ultrasound could not rule out an ovarian neoplasm.

The patient elected to undergo total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO). This option allowed for removal of a mass discovered during the procedure, minimized the risk for subsequent endometrial cancer, and reduced the chance of recurrence of the patient’s estrogen/progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer. The mass itself turned out to be a benign pedunculated fibroid tumor.

The patient was relieved and continues to recover well. A follow-up PET/CT scan is scheduled for three months from now.

Conclusion

PDB is a complex disease that challenges our current understanding of breast cancer and its diagnosis and treatment. It depends uniquely upon ductal (versus blood or lymphatic) spread. Little did Paget and his contemporaries realize they had opened up such a porthole into modern histology. Nor did they appreciate the fact that they had identified an insidious breast cancer that declares itself through the skin.

Today, it is understood that by the time nipple changes of PDB appear, an underlying breast cancer most likely exists. In at least 25% of cases, there is neither a palpable mass nor a positive mammogram finding. For this reason, clinicians must maintain a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for biopsy when there are skin changes at the nipple. This is especially true because the underlying lesions are more likely to be invasive cancers.

Surgical treatment will often mean complete mastectomy, whether simple, modified radical, or radical. This choice will be driven by the extent and location of the underlying disease. There is a role for partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy in those rare cases in which PDB is confined to the NAC with no underlying tumor. Partial mastectomy is also a consideration when the underlying tumor is small and/or located close to the NAC. Patients with PDB may consider whole-breast or NAC reconstruction once radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy are completed.

PDB remains a poignant reminder for all clinicians of the importance of a thorough clinical exam and a well-focused history in all patients at risk for breast cancer. Moreover, it is an enduring example of the fact that common symptoms sometimes do signify something uncommon and potentially life- changing.

References

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. In: Paget S, ed. Selected Essays and Addresses by Sir James Paget. London: Longmans, Green and Co.; 1902:145-148.

2. Sabel MS, Weaver DL. Paget disease of the breast. In: UpToDate. Chagpar AE, Hayes DF, Pierce LJ, eds. www.uptodate.com/contents/paget-disease-of-the-breast. Updated November 27, 2012. Accessed September 9, 2013.

3. Ortiz-Pagan S, Cunto-Amesty G, Narayan S. Effect of Paget’s disease on survival in breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2001;146:1267-1270.

4. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2012. www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2012. Accessed September 9, 2013.

5. Ashikari R, Park K, Huvos AG, Urban JA. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer. 1970;3:680-685.

6. Sakorafas GH, Blanchard K, Sarr MG, Farley DR. Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer Treatment Rev. 2001;27:9-18.

7. Chen C-Y, Sun L-M, Anderson BO. Paget disease of the breast: changing patterns of incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment in the U.S. Cancer. 2006;107:1448-1458.

8. Paone JF, Baker R. Pathogenesis and treatment of Paget’s disease of the breast. Cancer. 1981;48:825-829.

9. Nelson JA, Patel D, Mancuso P. Inflammatory breast cancer. ADVANCE for NPs and PAs. 2011;2(10):25-28.

10. Ngan V. Skin metastasis. DermNet NZ. New Zealand Dermatological Society. http://dermnetnz.org/lesions/metastasis.html. Accessed September 9, 2013.

11. Amano G, Yajima M, Moroboshi Y, et al. MRI accurately depicts underlying DCIS in a patient with Paget’s disease of the breast without palpable mass and mammography findings. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:149-153.

12. Burrell HC, Evans AJ. Radiological assessment of the breast: what the surgical oncologist needs to know. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:689-691.

13. Muttarak M, Siriya B, Kongmebhol P. Paget’s disease of the breast: clinical, imaging and pathologic findings: a review of 16 patients. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2001;7:e16, 1-7.

14. Laronga C, Hasson D, Hoover S, et al. Paget’s disease in the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:481-483.

15. Pezzi CM, Kukora JS, Audet IM. Breast conservation surgery using nipple-areolar resection for central breast cancers. Arch Surg. 2004;139:32-37.

16. Polgar C, Zsolt O, Tibor K, Janos F. Breast-conserving therapy for Paget disease of the nipple. Cancer. 2002;94:1904-1905.

17. Marshall JK, Griffith KA, Haffty BG, Solin LJ. Conservative management of Paget disease of the breast with radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2142-2149.

18. Vasquez B, Rousseau D, Hurd TC. Surgical management of breast cancer. Sem Oncol. 2007;34:234-240.

19. Mamounas EP. Continuing evolution in breast cancer surgical management. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1603-1606.

20. Nicholson BT, Harvey JA, Cohen MA. Nipple-areolar complex: normal anatomy and benign and malignant processes. Radiographics. 2009;29:509-523.