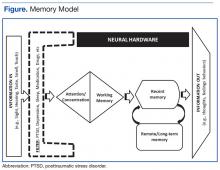

To appreciate these effects, it was important for participants in the memory skills classes to have some understanding of how memory works. The authors developed the Memory Model (Figure) as a visual aid and reference point to discuss the stages of new learning and how different aspects of brain activity are required for new learning and for memory to occur. This straightforward model is based on cognitive science and presented in layman’s terms. An important part of this model is the “filter” stage, which controls the information and stimuli that are available to the brain. Posttraumatic stress disorder involves involuntary emotional responses and efforts to avoid them and selects and colors the information that is processed in some situations (eg, avoidance of situations associated with trauma or dissociation of extreme memories). At other times, such as when a powerful stimulus is presented (eg, a helicopter flying close overhead), the filter may try to block out all inputs in order to preserve safety. The Memory Model also served as a visual aid during class discussions of normal cognitive aging.

The importance of being kind to oneself when lapses occur is emphasized in the class, and patients are urged to seek additional evaluation should lapses increase in severity or frequency.Class sessions incorporated specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART) goals, regular exercises based on mindfulness-based stress reduction approaches, and principles of behavioral activation.5 The SMART goals structure the sessions and permit customization of learning for participants. Class leaders record a goal for each participant and use these throughout the sessions to build rapport, develop communication, and teach memory skills.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction is an evidence-based treatment used in PTSD.6 It provides a counterpoint to the more didactic memory skills and is a method that even those with objective memory impairments can practice and apply successfully. Being in the current moment and emotional regulation are important skills to teach veterans as they learn to exert

some control over their filter and thus, how PTSD affects them. Behavioral activation brings together the literatures on nonpharmacotherapies for mood support as well as dementia prevention strategies (eg, increasing physical activity, social interaction, and cognitive stimulation).Organization

Class sessions occurred weekly for 1 hour for a total of 8 sessions. The weekly class topics included introduction to memory; mood disorders, cognition, and cognitive disorders; barriers to effective memory: assessing readiness for change; developing a routine and becoming organized; attention and concentration; memory improvement (strategies internal and external aids); and reassessing goals.

Over the 3 years of classes reported in this article, the class sizes varied from 4 to 12 participants based on veteran interest, retention, and room size. The classes were structured so that important content areas were covered but with enough elasticity so leaders and veterans would develop a rapport and explore in greater depth the topics that resonated most for the attendees. Group participation was strongly encouraged. Veterans were expressly informed that the class was not for treatment of PTSD and that evidence-based therapies were encouraged to address PTSD especially if their symptoms flared up when compared with previous levels. The attendees also understood that they did not receive formal cognitive or memory testing but were encouraged to pursue testing if they showed significant deficits.

Preliminary Findings

From spring 2012 until spring 2015, 69 veterans agreed to participate and attended at least 1 memory skills class. Eighty-seven percent of participants (n = 60) attended 4 or more classes. The mean age (SD) was 67.3 years (4.2). All the participants were men, and the race/ethnic distribution was similar to that of the aging veteran population and very close to racial demographics for Washington state: 80% white, 14% African American, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% Native American, and 2% unknown.

Attendees were asked, but not required, to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. These questionnaires included self-assessments of cognitive strategies and compensatory methods used; an assessment of concern regarding cognition, life satisfaction, and community integration; the PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C); and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).7,8 The questionnaire also included open response questions to providefeedback on what attendees liked about the classes and recommendations for improvements. The majority of comments for improvement focused on attendees’ desire for longer sessions and repeat offerings. Five veterans did not complete the full set of questionnaires at the beginning of the classes, and 7 did not complete the questionnaires at completion (the 2 subsets did not perfectly overlap).

At the start of the class, on average, veteran participants were experiencing mild depression and moderate symptoms of PTSD as measured by the GDS (n = 54) and the PCL-C (n = 56), respectively. Preliminary comparisons of ratings pre- and post-classes, using simple paired t tests, indicated a reduction in symptoms of depression on the GDS, improved sense of mastery over their memory symptoms, as well as improved quality of life ratings (all P < .01, no corrections). There was no evidence for a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms or report of elimination of cognitive difficulties. With the small sample and modest effects, the clinical significance of these scores cannot be determined. The authors are planning more detailed analyses on a larger set of participants, including measures of health care utilization before and after the class.