Falls often result in injuries with devastating outcomes. In the elderly, falls are the largest cause of injury, mortality, and functional decline, leading to 40% of nursing home admissions.1 Nationally, falls with injury are estimated to cost $19 billion in direct medical costs.2 According to the National Quality Forum (NQF), hospital falls resulting in injury are reportable events. Beginning in fiscal year 2015, reportable events labeled as hospital acquired conditions (HAC) are subject to nonpayment, creating increased regulatory and reimbursement pressure on hospitals.3

Due to the major impact of a fall, The Joint Commission (TJC) requires hospitals to assess a patient’s fall risk on admission and whenever the patient’s condition changes.4 Despite decades of research evaluating various predictive strategies to identify individuals at fall risk, nutritional issues as interactive risk factors have received little attention.

A comparative study on the validity of fall risk assessment scales revealed that tools claiming to predict risk factors do not work well.5 Falls are the result of multiple interactive, synergistic pathologies and risk factors. In a multivariate regression study conducted by Lichtenstein and colleagues in Canada, lower body weight was found to be a statistically significant risk factor for falling.6 In 2004, Oliver and colleagues conducted a systematic review of fall risk assessment tools that included validation testing with sufficient data to allow for calculation of sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values, odds ratios, and confidence intervals.5

Fourteen studies identified common fall risk factors. The majority of these studies identified impaired cognition as a risk factor.5 Of the 14 studies included in the systematic analysis of Oliver and colleagues,6-19 6 identified medications,6,8,11,12,17,18, and 8 noted weakness and unsteady gait as risk factors.6,9-11,14,16,18,19 Only 1 study noted anemia as a risk factor for falls among patients who were post cerebral vascular accident.11 Additionally, only 1 study noted an association between falls resulting in hip fracture and lower body weight.6

One in 4 adults admitted to a hospital is malnourished.20,21 Components of malnutrition, including but not limited to anemia, clinically significant weight loss, and vitamin D deficiency, may be unrecognized interactive risk factors that increase the risk of hospital falls. Malnutrition and dehydration symptoms include fatigue, dizziness, irritability, loss of muscle mass, impulsivity, and the potential for poor judgment. Therefore, it is likely that the severity of specific malnutrition parameters is associated with recurrent falls and possibly injurious falls.

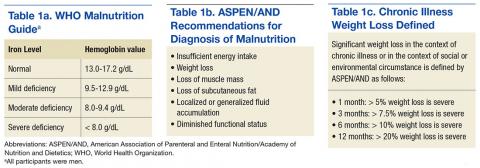

Hunger and inadequate food intake due to chronic disease or chronic food insecurity are real issues for the elderly. Insufficient caloric intake often leads to slow, progressive, and often unnoticed weight loss. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and the American Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) have defined clinically significant weight loss categories to aid in the diagnosis of malnutrition. To aid in the diagnosis of various degrees of malnutrition, clinically significant weight loss is classified as ≥ 5% weight loss in 30 days; ≥ 7.5% weight loss in 90 days; > 10% in 180 days.21 The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies iron deficiency measured by hemoglobin (Hgb) value (for men < 13 g/dL) as the most common and widespread nutritional disorder in the world (Tables 1a, 1b, and 1c).22

Eat Well, Fall Less is a retrospective chart review approved by the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC (LSCVAMC) Internal Review Board. The review seeks to determine whether degree of weight loss and decline in Hgb and vitamin D deficiency, factors of malnutrition, are present in recurrent fallers vs single-event fallers. Researchers hypothesized that individuals who experienced recurrent falls during hospitalization would demonstrate a greater degree of clinically significant weight loss compared with those who had experienced a single fall. The second hypothesis was that recurrent fallers also would have lower Hgb values than that of single-event fallers. The tertiary hypothesis was that individuals with a greater degree of vitamin D deficiency were more likely to be recurrent fallers compared with single-event fallers.

In addition, dementia has been previously identified as an independent risk factor for falls and recurrent falls.23 During phase 2 of the study, the researchers hypothesized that in individuals with dementia, the concurrent diagnosis of malnutrition would be greatest in the recurrent fall population. A total of 30 subjects were included in the analysis.

Methods

Patient record search of note titles for falls was compiled daily. A random sample of 170 veterans who had experienced a fall was screened for study inclusion. Of the 170 charts, data from a total of 120 veterans who experienced a documented fall during a hospitalization between October 1, 2010 and October 31, 2012, were included in this analysis.