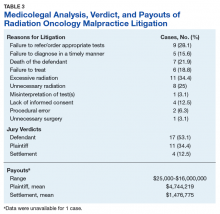

Excessive radiation (n = 11, 34.4%), unnecessary radiation (n = 8, 25%), and a failure to refer and/or order appropriate tests (n = 9, 28.1%) were the 3 most commonly alleged causes of malpractice. A lack of informed consent was implicated in less than one-seventh of cases (4; 12.5%). In 7 (21.9%) cases, the patient passed away.

Between 1985 and 2015, decisions were made in radiation oncologists’ favor in more than half of the cases. The jury ruled for the plaintiff in 11 (34.4%) cases and for the defendant in 17 (53.1%) cases. Settlements were reached in 4 (12.5%) cases, with a mean payout of $1,476,775.

Cases that proceeded to trial had a mean payout of $4,744,219. Payouts ranged from $25,000 to $16,000,000.Discussion

A physician’s duty is to provide medical care within the standard of care. In the courtroom, a radiation oncologist is judged on what a “reasonably prudent” radiation oncologist would do in similar circumstances.26 The plaintiff must establish the standard of care for the patient’s specific diagnosis with evidence, which is often accomplished through expert testimony. A physician is deemed negligent when deviating from this standard of care. The plaintiff must establish 4 factors to be awarded compensation for medical negligence: (1) the physician owed a professional duty to the patient such as the doctor-patient relationship; (2) the physician breeched this duty or failed to meet the standard of care; (3) proximate cause—the breach of duty by the physician directly caused the patient’s injury; and (4) the patient experienced emotional and/or physical damage while in the care of the physician.27

Reasons for Malpractice Claims

The WestlawNext search revealed 3 top theories of breach of standard of care: excessive radiation, unnecessary radiation, and a failure to refer and/or order appropriate tests. As a result, these theories can be interpreted as medical malpractice law in evolution. In other words, the courts still may be laying groundwork to clarify these theories.

However, a more cynical interpretation of why these 3 top theories of breech of standard of care were seen would note the practice of using expert witness testimony as “hired guns” in the U.S. legal system. Plaintiff attorneys know that use of expert witnesses can increase the attorney’s billable hours during the discovery phase and can decrease the likelihood that the case would be thrown out as lacking merit. Nevertheless, when the claim eventually does go to trial, it may lack merit, but not before plaintiff and defense attorneys complete many hours of work. This use of the legal system for financial gains can potentially confound the true reasons why the search resulted in these 3 top theories of breach of standard of care.

A lack of informed consent was not a major issue and was cited only in 4 (12.5%) cases as the cause of alleged malpractice. This finding was reassuring, as informed consent is an important issue that reinforces the physician-patient relationship and enhances patient trust. Previous studies found a perceived lack of informed consent as a basis for a malpractice claim in more than 34% of otolaryngology cases,25% of cranial nerve surgery cases,and 39% of facial plastic surgery cases.28-30 Perhaps the physician patient discussion in radiation oncology may be different compared with that of surgery, as treatments in radiation oncology are guided by large clinical trials, and patients are often referred after discussions with other specialty providers, such as surgeons and medical oncologists. Improving patients’ understanding of their radiation treatment plans is important in reducing malpractice claims relating to informed consent, and recent studies have identified areas where patient education can be improved.31,32

Settlements

Although settlements were reached in a minority of cases, the monetary value of jury verdicts favoring the plaintiff were 3-fold higher than those of out-of-court settlements. Specifically, cases that were settled had a mean payout of $1,476,775, which sharply contrasts with cases that proceeded to trial and a mean payout of $4,744,219. The highest jury award to the plaintiff was $16,000,000, involving a case where it was determined that a double dose of radiation was delivered to a patient’s shoulder. In a simple risk-reward analysis, this suggests that radiation oncologists should consider settling out of court if a malpractice guilty verdict seems possible. However, given the retrospective nature of the analysis, only limited conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of such a strategy.

Regardless, cases that were settled or judged on the plaintiff’s behalf were for a much higher value in radiation oncology compared with indemnity payment claims data in other high-risk specialties (emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecologic surgery, and radiology).33 It is important to highlight the magnitude of real and perceived harm that can be associated with radiation oncology. Regarding perceived harm, the public may lack an understanding of how radiation works. Interestingly, even though the perceived harm may be misplaced, the real harm is still there. Unlike other specialties where some errors can be reversed (ie, if heparin is mistakenly administered, its effects can be reversed by protamine sulfate), once radiation is delivered, it is not reversible. The harm is permanent and can cause disability.

Settlements are often lower in legal cases due to insurance policy limitations, the time line of award payout (settlement funds are paid more rapidly, as verdict awards are dependent on the conclusion of the case), and the inherent risk that an appeals court may overturn a verdict or reduce the amount of the award.34 For all the radiation oncology cases that proceeded to trial, more than half (53.1%) of the cases were in favor of the physician (Table 3). While this is positive news for radiation oncologists, it is still lower than the national average of 75% of malpractice verdicts in favor of the physician.34,35 In contrast, 65% of colorectal surgery cases resulted in a verdict in favor of the physician.36