Despite important advances in treatment and prevention over the past 30 years, HIV remains a significant public health concern in the US, with nearly 40,000 new HIV infections. annually.1 Among the estimated 1.1 million Americans currently living with HIV, 1 in 8 remains undiagnosed, and only half (49%) are virally suppressed.2 Although data demonstrate that viral suppression virtually eliminates the risk of transmission among people living with HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV remains an integral part of a coordinated effort to reduce transmission. Uptake of PrEP is particularly vital considering the large percentage of people in the US living with HIV who are not virally suppressed because they have not started, are unable to stay on HIV antiretroviral treatment, or have not been diagnosed.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest single provider of care to HIV-infected individuals in the US, with more than 28,000 veterans in care with HIV in 2016 (data from the VA National HIV Clinical Registry Reports, written communication from Population Health Service, Office of Patient Care Services, January 2018). Furthermore, according to written communication from the VA Population Health Service Office of Patient Care Services, in January 2018 the VA had an undiagnosed incidence (the rate of screening tests in 2016 identifying new positive HIV diagnoses) above the CDC’s recommended threshold of ≥ 0.1%.3 Regional variations in newly diagnosed HIV infections within the VA health care system generally mirror those of the national HIV epidemic in the US, making prevention imperative, particularly in regions with a greater prevalence of undiagnosed individuals.

The only FDA-approved medication for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), a fixed-dose combination of 2 antiretroviral medications that are also used to treat HIV. Its efficacy has been proven among numerous populations at risk for HIV, including those with sexual and injection drug use risk factors.4,5 Use of TDF/FTC for PrEP has been available at the VA since its July 2012 FDA approval. In May 2014, the US Public Health Service (PHS) and the US Department of Health and Human Services released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for PrEP. Soon after, in September 2014, the VA released more formal guidance on the use of TDF/FTC for HIV PrEP as outlined by the PHS.6 Similar to patterns outside the VA, PrEP uptake across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has been modest and variable.

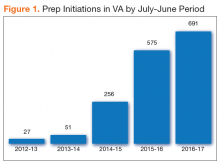

A recent VHA analysis of the variability in PrEP uptake identified about 1,600 patients who had been prescribed PrEP in the VA as of June 2017 among about 6 million veterans in care. Across VA medical facilities, the absolute number of PrEP initiations ranged from 0 to 109 with the maximum PrEP initiation rate at 146.4/100,000 veterans in care. Eight facilities did not initiate a single PrEP prescription over the 5-year period. This study presents strategicefforts undertaken by the VA to increase access to and uptake of PrEP across the health care system and to decrease disparities in HIV prevention care.

VA National PrEP Working Group

In the beginning of 2017, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions (HHRC) programs within the VHA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a national working group to better measure and address the gaps in PrEP usage across the health care system. This multidisciplinary PrEP Working Group was composed of more than 40 members with expertise in HIV clinical care and PrEP, including physicians, clinical pharmacists, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), social workers, psychologists, implementation scientists, and representatives from other VA programs with a relevant programmatic or policy interest in PrEP.

Implementation Targets

The National PrEP Working Group identified increased PrEP uptake across the VHA system as the primary implementation target with a specific focus on increasing PrEP use in primary care clinics and among those at highest risk. As noted earlier, overall uptake of PrEP across VHA medical facilities has been modest; however, new PrEP initiations have increased in each 12-month period since FDA approval (Figure 1).

To rapidly understand barriers to accessing PrEP, the National PrEP Working Group developed and deployed an informal survey to HIV clinicians at all VA facilities, with nearly half responding (n = 68). These frontline providers identified several important and common barriers inhibiting PrEP uptake, including knowledge gaps among providers without infectious diseases training in the indication, use, and monitoring of PrEP; limited understanding about the availability of PrEP in the VA; and uncertainty about how to access training or education to become competent to prescribe PrEP. A national, non-VA survey of primary care providers from 2009 to 2012 found an increased willingness and interest in providing PrEP following targeted education and training.7

Patient adherence was not identified by providers as a significant barrier to PrEP uptake in this informal survey. A recent analysis of adherence among a national cohort of veterans on HIV PrEP in VA care between July 2012 and June 2016 found that adherence in the first year of PrEP was high with some differences detected by age, race, and gender.8

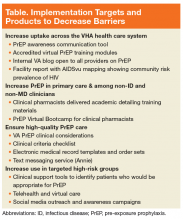

As an initial step in addressing these identified barriers to prescribing PrEP in the VHA, the National PrEP Working Group developed several provider education materials, trainings, and support tools to impact the overarching goal, and identified implementation targets of increasing access outside of primary care and among noninfectious disease and nonphysician clinicians, ensuring high-quality PrEP care in all settings, and targeting PrEP uptake to at-risk populations (Table).

Tools specifically designed to increase overall system level awareness within the VA included (1) a PrEP Awareness Communication Tool Kit made centrally available as a repository for all PrEP products, tools, and other resources; (2) nationally accredited, virtual trainings in 2 formats made broadly available to all potentially prescribing disciplines; (3) creation of an internal VA blog dedicated to PrEP to foster communication and dialogue among providers of all disciplines; and (4) aggregated facility reports designed to help guide local quality improvement efforts to improve PrEP access and uptake.