Penile cancer is rare with a worldwide incidence of 0.8 cases per 100,000 men.1 The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) followed by soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and Kaposi sarcoma.2 Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common STS subtype at this location.3 Approximately 50 cases of penile LMS have been reported in the English literature, most as isolated case reports while Fetsch and colleagues reported 14 cases from a single institute.4 We present a case of penile LMS with a review of 31 cases. We also describe presentation, treatment options, and recurrence pattern of this rare malignancy.

Case Presentation

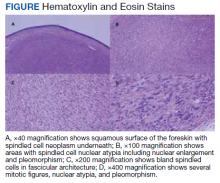

A patient aged 70 years presented to the urology clinic with 1-year history of a slowly enlarging penile mass associated with phimosis. He reported no pain, dysuria, or hesitancy. On examination a 2 × 2-cm smooth, mobile, nonulcerating mass was seen on the tip of his left glans without inguinal lymphadenopathy. He underwent circumcision and excision biopsy that revealed an encapsulated tan-white mass measuring 3 × 2.2 × 1.5 cm under the surface of the foreskin. Histology showed a spindle cell tumor with areas of increased cellularity, prominent atypia, and pleomorphism, focal necrosis, and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms. The tumor stained positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Ki-67 staining showed foci with a very high proliferation index (Figure). Resection margins were negative. Final Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer score was grade 2 (differentiation, 1; mitotic, 3; necrosis, 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show evidence of metastasis. The tumor was classified as superficial, stage IIA (pT1cN0cM0). Local excision with negative margins was deemed adequate treatment.

Discussion

Penile LMS is rare and arises from smooth muscles, which in the penis can be from dartos fascia, erector pili in the skin covering the shaft, or from tunica media of the superficial vessels and cavernosa.5 It commonly presents as a nodule or ulcer that might be accompanied by paraphimosis, phimosis, erectile dysfunction, and lower urinary tract symptoms depending on the extent of local tissue involvement. In our review of 31 cases, the age at presentation ranged from 38 to 85 years, with 1 case report of LMS in a 6-year-old. The highest incidence was in the 6th decade. Tumor behavior can be indolent or aggressive. Most patients in our review had asymptomatic, slow-growing lesions for 6 to 24 months before presentation—including our patient—while others had an aggressive tumor with symptoms for a few weeks followed by rapid metastatic spread.6,7

Histology and Staging

Diagnosis requires biopsy followed by histologic examination and immunohistochemistry of the lesion. Typically, LMS shows fascicles of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, pleomorphisms, and necrotic regions. Mitotic rate is variable and usually > 5 per high power field. Cells stain positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.8 TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) stage is determined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines for STS.

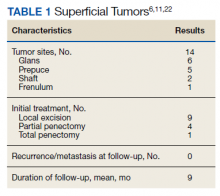

Pratt and colleagues were the first to categorize penile LMS as superficial or deep.9 The former includes all lesions superficial to tunica albuginea while the latter run deep to this layer. Anatomical distinction is an important factor in tumor behavior, treatment selection, and prognosis. In our review, we found 14 cases of superficial and 17 cases of deep LMS.

Treatment

There are no established guidelines on optimum treatment of penile LMS. However, we can extrapolate principles from current guidelines on penile cancer, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, and limb sarcomas. At present, the first-line treatment for superficial penile LMS is wide local excision to achieve negative margins. Circumcision alone might be sufficient for tumors of the distal prepuce, as in our case.10 Radical resection generally is not required for these early-stage tumors. In our review, no patient in this category developed recurrence or metastasis regardless of initial surgery type (Table 1).6,11,12

For deep lesions, partial—if functional penile stump and negative margins can be achieved—or total penectomy is required.10 In our review, more conservative approaches to deep tumors were associated with local recurrences.7,13,14 Lymphatic spread is rare for LMS. Additionally, involvement of local lymph nodes usually coincides with distant spread. Inguinal lymph node dissection is not indicated if initial negative surgical margins are achieved.

For STS at other sites in the body, radiation therapy is recommended postoperatively for high-grade lesions, which can be extrapolated to penile LMS as well. The benefit of preoperative radiation therapy is less certain. In limb sarcomas, radiation is associated with better local control for large-sized tumors and is used for patients with initial unresectable tumors.15 Similar recommendation could be extended to penile LMS with local spread to inguinal lymph nodes, scrotum, or abdominal wall. In our review, postoperative radiation therapy was used in 3 patients with deep tumors.16-18 Of these, short-term relapse occurred in 1 patient.

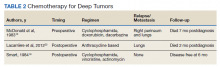

Chemotherapy for LMS remains controversial. The tumor generally is resistant to chemotherapy and systemic therapy, if employed, is for palliative purpose. The most promising results for adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable STS is seen in limb and uterine sarcomas with high-grade, metastatic, or relapsed tumors but improvement in overall survival has been marginal.19,20Single and multidrug regimens based on doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and gemcitabine have been studied with results showing no efficacy or a slight benefit.8,21 Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for penile STS have not been studied. In our review, postoperative chemotherapy was used for 2 patients with deep tumors and 1 patient with a superficial tumor while preoperative chemotherapy was used for 1 patient.16,18,22 Short-term relapse was seen in 2 of 4 of these patients (Table 2).