Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a significant cause of morbidity, mortality, and health care costs in the US.1,2 Surgery can be the inciting cause for exposure to an opioid; as many as 23% of patients develop chronic OUD following surgery.3,4 Patients with a history of substance use, mood disorders, anxiety, or previous chronic opioid use (COU) are at risk for relapse, dose escalation, and poor pain control after high-risk surgery, such as orthopedic joint procedures.5 Recently focus has been on identifying high-risk patients before orthopedic joint surgery and implementing evidence-based strategies that reduce the postoperative incidence of COU.

A transitional pain service (TPS) has been shown to reduce COU for high-risk surgical patients in different health care settings.6-9 The TPS model bundles multiple interventions that can be applied to patients at high risk for COU within a health care system. This includes individually tailored programs for preoperative education or pain management planning, use of multimodal analgesia (including regional or neuraxial techniques or nonopioid systemic medications), application of nonpharmacologic modalities (such as cognitive-based intervention), and a coordinated approach to postdischarge instructions and transitions of care. These interventions are coordinated by a multidisciplinary clinical service consisting of anesthesiologists and advanced practice clinicians with specialization in acute pain management and opioid tapering, nurse care coordinators, and psychologists with expertise in cognitive behavioral therapy.

TPS has been shown to reduce the incidence of COU for patients undergoing orthopedic joint surgery, but its impact on health care use and costs is unknown.6-9 The TPS intervention is resource intensive and increases the use of health care for preoperative education or pain management, which may increase the burden of costs. However, reducing long-term COU may reduce the use of health care for COU- and OUD-related complications, leading to cost savings. This study evaluated whether the TPS intervention influenced health care use and cost for inpatient, outpatient, or pharmacy services during the year following orthopedic joint surgery compared with that of the standard pain management care for procedures that place patients at high risk for COU. We used a difference-in-differences (DID) analysis to estimate this intervention effect, using multivariable regression models that controlled for unobserved time trends and cohort characteristics.

METHODS

This was a quasi-experimental study of patients who underwent orthopedic joint surgery and associated procedures at high risk for COU at the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Healthcare System (VASLCHS) between January 2016 through April 2020. The pre-TPS period between January 2016 through December 2017 was compared with the post-TPS period between January 2018 to September 2019. The control patient cohort was selected from 5 geographically diverse VA health care systems throughout the US: Eastern Colorado, Central Plains (Nebraska), White River Junction (Vermont), North Florida/South Georgia, and Portland (Oregon). By sampling health care costs from VA medical centers (VAMCs) across these different regions, our control group was generalizable to veterans receiving orthopedic joint surgery across the US. This study used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a repository of nearly all clinical and administrative data found in electronic health records for VA-provided care and fee-basis care paid for by the VA.10 All data were hosted and analyzed in the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) workspace. The University of Utah Institutional Review Board and the VASLCHS Office of Research and Development approved the protocol for this study.

TPS Intervention

The VASLCHS TPS has already been described in detail elsewhere.6,7 Briefly, patients at high risk for COU at the VASLCHS were enrolled in the TPS program before surgery for total knee, hip, or shoulder arthroplasty or rotator cuff procedures. The TPS service consists of an anesthesiologist and advanced practice clinician with specialization in acute pain management and opioid tapering, a psychologist with expertise in cognitive behavioral therapy, and 3 nurse care coordinators. These TPS practitioners work together to provide preoperative education, including setting expectations regarding postoperative pain, recommending nonopioid pain management strategies, and providing guidance regarding the appropriate use of opioids for surgical pain. Individual pain plans were developed and implemented for the perioperative period. After surgery, the TPS provided recommendations and support for nonopioid pain therapies and opioid tapers. Patients were followed by the TPS team for at least 12 months after surgery. At a minimum, the goals set by TPS included cessation of all opioid use for prior nonopioid users (NOU) by 90 days after surgery and the return to baseline opioid use or lower for prior COU patients by 90 days after surgery. The TPS also encouraged and supported opioid tapering among COU patients to reduce or completely stop opioid use after surgery.

Patient Cohorts

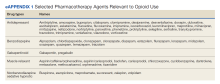

Veterans having primary or revision total knee, hip, or shoulder arthroplasty or rotator cuff repair between January 1, 2016, and September 30, 2019, at the aforementioned VAMCs were included in the study. Patients who had any hospitalization within 90 days pre- or postindex surgery or who died within 8 months after surgery were excluded from analysis. Patients who had multiple surgeries during the index inpatient visit or within 90 days after the index surgery also were excluded. Comorbid conditions for mental health and substance use were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision Clinical Modification (ICD-10) codes or 9th revision equivalent grouped by Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCS-R).11 Preoperative exposure to clinically relevant pharmacotherapy (ie, agents associated with prolonged opioid use and nonopioid adjuvants) was captured using VA outpatient prescription records (eAppendix 1).