Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is an important public health concern. Deep venous thrombosis is estimated to affect 10% to 20% of medical (nonsurgical) patients, 15% to 40% of stroke patients, and 10% to 80% of critical care patients who are not prophylaxed.1 Venous thromboembolism is associated with significant resource utilization, long-term sequelae, recurrent events, and sudden death.2

The current guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians recommend use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis as the preferred strategy for nonsurgical (or medical) patients (IB, formerly IA, recommendation) and for critically ill patients (2C recommendation) at low risk for bleeding.1,3 Mechanical (or nonpharmacologic) thromboprophylaxis (eg, intermittent pneumatic compression) is an alternative for those at increased risk for bleeding (2C recommendation).3 Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in high-risk patients, similar to those studied in randomized controlled clinical trials, reduces the occurrence of symptomatic DVT by 34 events per 1,000 patients treated.3 However, data are conflicting regarding mortality benefit.4,5

Related: Trends in Venous Thromboembolism

The Joint Commission adopted any thromboprophylaxis (measure includes pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic strategies) as a core discretionary measure in the ORYX (National Quality Hospital Measures) program. The ORYX measurements are intended to support Joint Commission-accredited organizations in institutional quality improvement efforts. The thromboprophylaxis core measure became effective May 2009 and remains as an option for hospitals to meet the 4 core measure set accreditation requirement. A top-performing hospital should provide this measure to applicable patients ≥ 95% of the time, according to the Joint Commission.6 The Joint Commission does not encourage use of any risk assessment model (RAM), such as the Padua Prediction Score to preferentially select high-risk medical patients.3

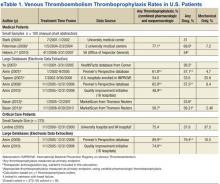

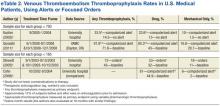

A disparity exists between thromboprophylaxis recommendations and practices in the nonsurgical patient, even when electronic prompts or alerts are available (eTables 1 and 2). In the U.S., pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is administered to 23.6% to 81.1% of medical patients and 37.9% to 79.4% of critical care patients.7-21 In most cases, these rates are liberal estimates, because they include patients who are already on therapeutic anticoagulation or may have received only 1 prophylactic dose during hospitalization.8-11,13-20 When studies exclude patients receiving therapeutic (or treatment doses) anti-coagulation, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates are substantially lower, typically 31% to 33% for medical patients and 37.9% for critical care patients.7,12,21 Furthermore, when studies examine appropriateness of thromboprophylaxis (eg, within the first 2 days of hospitalization or at the correct dose, correct time, or predefined duration), calculations are often less robust.10,11,13,14,22,23

The VHA uses thromboprophylaxis of surgical patients as an external peer review (EPR) performance measure (PM). With the great attention to this national measure, Altom and colleagues reported 89.9% of surgeries adhered.24 Before 2015, VTE thromboprophylaxis EPR PM did not exist. However, the VHA has initiated efforts to assure that providers are adherent to the new indications, which include VTE prophylaxis and treatment.

There is little published literature evaluating VHA performance.Quraishi and colleagues reported a pharmacologic prophylaxis rate of 63% in nonsurgical patients at a single VAMC, facilitated by the use of an admission VTE order set. Unfortunately, their estimate allowed inclusion of 5% of patients receiving treatment doses of anticoagulation and failed to provide any estimates on regimen appropriateness (eg, correct dose, correct time, or correct duration).18 Lentine and colleagues documented a pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48% for a subset of veteran critical care patients who were not already receiving indicated therapeutic anticoagulants.21

Veterans have poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource use than do nonveterans; therefore, it is postulated that veterans can derive clinical benefit from improved attention to thromboprophylaxis benchmarking, performance improvement, and potentially, implementation of electronic alerts or reminder tools.25 Nationally, VHA has no formal inpatient reminder tools to trigger use of thromboprophylaxis for high-risk medical patients, although individual health care systems may have created alerts or tools. Some studies demonstrated that order sets and electronic tools are helpful, whereas others demonstrated potential for harm.17-20,26,27

For any hospitalization at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS), the only electronic prompt to order VTE thromboprophylaxis occurs when the admission order set is completed. But the prompt can be readily bypassed if the quick admission orders are selected. Although no further electronic prompts in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) are invoked following admission, the authors hypothesized that the rate of VTE thromboprophylaxis, specifically pharmacologic, in a subset of veterans with respiratory disease will be higher than the usual published rates.

Purpose and Relevance

This study’s primary aim was to assess the rate of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in veterans with pulmonary disease who were admitted for a nonsurgical stay. The 2 secondary aims were to determine whether thromboprophylaxis was appropriate and to characterize whether differences exist for pharmacologic prophylaxis according to level of care (medical critical care unit [CCU] vs acute care medical ward).