The Cost of Oncology Drugs: A Pharmacy Perspective, Part 1, appeared in the Federal Practitioner February 2016 special issue “Best Practices in Hematology and Oncology” and can be accessed here.

Health care costs are the fastest growing financial segment of the U.S. economy. The cost of medications, especially those for treating cancer, is the leading cause of increased health care spending.1 Until recently, the discussion of the high costs of cancer treatment was rarely made public.

Part 1 of this article focused on the emerging discussion of the financial impact of high-cost drugs in the U.S. Part 2 will focus on the drivers of increasing oncology drug costs and the challenges high-cost medications pose for the VA. The article also will review the role of the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) in evaluating new oncology agents. Also presented are the clinical guidance tools designed to aid the clinician in the cost-effective use of these agents and results of a nationwide survey of VA oncology pharmacists regarding the use of cost-containment strategies.

Cost Drivers

Many factors are driving increased oncology drug costs within the VA. Although the cost of individual drugs has the largest impact on the accelerating cost of treating each patient, other clinical and social factors may play a role.

Increasing Cost of Individual Drugs

Drug pricing is not announced until after FDA approval. Oncology drugs at the high end of the cost spectrum are rarely curative and often add only weeks or months to overall survival (OS), the gold standard. Current clinical trial design often uses progression free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint, which makes the use of traditional pharmacoeconomic determinations of value difficult. In addition, many new drugs are first in class and/or have narrow indications that preclude competition from other drugs. Although addressing the issue of the market price for drugs seems to be one that is not controllable, there is increasing demand for drug pricing reform.2

Many believe drug prices should be linked directly to clinical benefit. In a recent article, Goldstein and colleagues proposed establishing a value-based price for necitumumab based on clinical benefit, prior to FDA approval.3 When this analysis was done, necitumumab was pending FDA approval in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine for the treatment of squamous carcinoma of the lung. Using clinical data from the SQUIRE trial on which FDA approval was based, the addition of necitumumab to the chemotherapy regimen led to an incremental survival benefit of 0.15 life-years and 0.11 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY).4 Using a Markov model to evaluate cost-effectiveness, these authors established that the price of necitumumab should be from $563 to $1,309 per cycle. Necitumumab was approved by the FDA on November 24, 2015, with the VA acquisition cost, as of May 2016, at $6,100 per cycle.

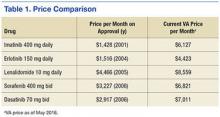

Lack of Generic Products

The approval of generic alternatives for targeted oncology agents should reduce the cost of treating oncology patients. However, since imatinib was approved in May 2001, no single targeted agent had become available as a generic until February 1, 2016, when generic imatinib was made available in the U.S. following approval by the FDA. Currently, generic imatinib is not used in the VA due to lack of Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) contract pricing, which leads to a generic cost that is much higher than the brand-name drug, Gleevec ($6,127 per month vs $9,472 per month for the generic). The reality is that many older agents have steadily increased in price, outpacing inflation (Table 1).5

Aging U.S. Population

Advancing age is the most common risk factor for cancer, leading to an increase in the incidence and treatment of cancer. Because many newer agents are considered easier to tolerate than are traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, clinicians have become more comfortable treating elderly patients, and geriatric oncology has become an established subspecialty within oncology.

Changing Treatment Paradigms

The use of targeted therapies is changing the paradigm from the acute treatment of cancer to chronic cancer management. Most targeted therapies are continued until disease progression or toxicity, leading to chronic, open-ended treatment. This approach is in contrast to older treatment approaches such as chemotherapy, which is often given for a limited duration followed by observation. When successful, chronic treatment with targeted agents can lead to unanticipated high costs. The following current cases at the VA San Diego Healthcare System illustrate this point:

- Renal cell carcinoma: 68-year-old man diagnosed in 2005 with a recurrence in 2012

- High-dose interleukin-2 (2 cycles); sunitinib (3.3 years); pazopanib (2 months); everolimus (2 months); sorafenib (3 months); axitinib (7 months)