User login

A Multi-Center Retrospective Study Evaluating Palliative Antineoplastic Therapy Administered and Medication De-escalation in Veteran Cancer Patients Toward the End-of-life

BACKGROUND: Metastatic cancer patients near endof- life often continue to receive aggressive cancer treatments and are prescribed many chronic futile medications. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends avoiding use of chemotherapy towards end of life in solid tumor patients with poor performance due to potential risk of adverse events.

OBJECTIVES: The objective of this multi-site study was to evaluate the incidence of palliative antineoplastic therapy administration for patients with metastatic cancer as well as the number of patients who received non-essential medications at thirty and fourteen days prior to death.

METHODS: This was a retrospective, multicenter study conducted at 6 Veteran Affairs Medical Centers: Southern Arizona, Lexington, Robley Rex, John D Dingell, San Diego, and Richard L Roudebush. The electronic medical record system identified patients deceased between July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2018 with metastatic lung, colorectal, prostate, pancreatic cancer, or melanoma. Data were analyzed using descriptive analysis.

RESULTS: A total of 651 patients were included in the multicenter study, and the average age of veterans was 71 years with metastatic lung cancer being the most common malignancy at 55%. Within 30 days and 14 days of death, respectively, 24.6% and 13.2% had an antineoplastic agent. Within the last 30 days of life, 45% of patients received systemic chemotherapy, 38% received oral targeted agent, and 17% received immunotherapy. Within last 30 days of life, 50% received a first line treatment, 26.9% received a second line treatment, and 23.2% received ≥ third line of treatment. There was a large proportion of patients hospitalized (n=208) and/ or had ED visits (n=204) due to antineoplastic treatment and/or complications from malignancy. Within the last 30 days of death, 76.3% had ≥ 1 active chronic medication. Palliative care providers were the top recommenders for medication de-escalation.

CONCLUSION: The results of this multi-site retrospective study provides insight into the management of endof- life care for metastatic cancer patients across the VA health care system. Overall the results of this study demonstrate an opportunity for promoting detailed discussions with patients regarding palliative care earlier after diagnosis of metastatic cancer.

BACKGROUND: Metastatic cancer patients near endof- life often continue to receive aggressive cancer treatments and are prescribed many chronic futile medications. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends avoiding use of chemotherapy towards end of life in solid tumor patients with poor performance due to potential risk of adverse events.

OBJECTIVES: The objective of this multi-site study was to evaluate the incidence of palliative antineoplastic therapy administration for patients with metastatic cancer as well as the number of patients who received non-essential medications at thirty and fourteen days prior to death.

METHODS: This was a retrospective, multicenter study conducted at 6 Veteran Affairs Medical Centers: Southern Arizona, Lexington, Robley Rex, John D Dingell, San Diego, and Richard L Roudebush. The electronic medical record system identified patients deceased between July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2018 with metastatic lung, colorectal, prostate, pancreatic cancer, or melanoma. Data were analyzed using descriptive analysis.

RESULTS: A total of 651 patients were included in the multicenter study, and the average age of veterans was 71 years with metastatic lung cancer being the most common malignancy at 55%. Within 30 days and 14 days of death, respectively, 24.6% and 13.2% had an antineoplastic agent. Within the last 30 days of life, 45% of patients received systemic chemotherapy, 38% received oral targeted agent, and 17% received immunotherapy. Within last 30 days of life, 50% received a first line treatment, 26.9% received a second line treatment, and 23.2% received ≥ third line of treatment. There was a large proportion of patients hospitalized (n=208) and/ or had ED visits (n=204) due to antineoplastic treatment and/or complications from malignancy. Within the last 30 days of death, 76.3% had ≥ 1 active chronic medication. Palliative care providers were the top recommenders for medication de-escalation.

CONCLUSION: The results of this multi-site retrospective study provides insight into the management of endof- life care for metastatic cancer patients across the VA health care system. Overall the results of this study demonstrate an opportunity for promoting detailed discussions with patients regarding palliative care earlier after diagnosis of metastatic cancer.

BACKGROUND: Metastatic cancer patients near endof- life often continue to receive aggressive cancer treatments and are prescribed many chronic futile medications. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends avoiding use of chemotherapy towards end of life in solid tumor patients with poor performance due to potential risk of adverse events.

OBJECTIVES: The objective of this multi-site study was to evaluate the incidence of palliative antineoplastic therapy administration for patients with metastatic cancer as well as the number of patients who received non-essential medications at thirty and fourteen days prior to death.

METHODS: This was a retrospective, multicenter study conducted at 6 Veteran Affairs Medical Centers: Southern Arizona, Lexington, Robley Rex, John D Dingell, San Diego, and Richard L Roudebush. The electronic medical record system identified patients deceased between July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2018 with metastatic lung, colorectal, prostate, pancreatic cancer, or melanoma. Data were analyzed using descriptive analysis.

RESULTS: A total of 651 patients were included in the multicenter study, and the average age of veterans was 71 years with metastatic lung cancer being the most common malignancy at 55%. Within 30 days and 14 days of death, respectively, 24.6% and 13.2% had an antineoplastic agent. Within the last 30 days of life, 45% of patients received systemic chemotherapy, 38% received oral targeted agent, and 17% received immunotherapy. Within last 30 days of life, 50% received a first line treatment, 26.9% received a second line treatment, and 23.2% received ≥ third line of treatment. There was a large proportion of patients hospitalized (n=208) and/ or had ED visits (n=204) due to antineoplastic treatment and/or complications from malignancy. Within the last 30 days of death, 76.3% had ≥ 1 active chronic medication. Palliative care providers were the top recommenders for medication de-escalation.

CONCLUSION: The results of this multi-site retrospective study provides insight into the management of endof- life care for metastatic cancer patients across the VA health care system. Overall the results of this study demonstrate an opportunity for promoting detailed discussions with patients regarding palliative care earlier after diagnosis of metastatic cancer.

The Cost of Oncology Drugs: A Pharmacy Perspective, Part 2

The Cost of Oncology Drugs: A Pharmacy Perspective, Part 1, appeared in the Federal Practitioner February 2016 special issue “Best Practices in Hematology and Oncology” and can be accessed here.

Health care costs are the fastest growing financial segment of the U.S. economy. The cost of medications, especially those for treating cancer, is the leading cause of increased health care spending.1 Until recently, the discussion of the high costs of cancer treatment was rarely made public.

Part 1 of this article focused on the emerging discussion of the financial impact of high-cost drugs in the U.S. Part 2 will focus on the drivers of increasing oncology drug costs and the challenges high-cost medications pose for the VA. The article also will review the role of the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) in evaluating new oncology agents. Also presented are the clinical guidance tools designed to aid the clinician in the cost-effective use of these agents and results of a nationwide survey of VA oncology pharmacists regarding the use of cost-containment strategies.

Cost Drivers

Many factors are driving increased oncology drug costs within the VA. Although the cost of individual drugs has the largest impact on the accelerating cost of treating each patient, other clinical and social factors may play a role.

Increasing Cost of Individual Drugs

Drug pricing is not announced until after FDA approval. Oncology drugs at the high end of the cost spectrum are rarely curative and often add only weeks or months to overall survival (OS), the gold standard. Current clinical trial design often uses progression free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint, which makes the use of traditional pharmacoeconomic determinations of value difficult. In addition, many new drugs are first in class and/or have narrow indications that preclude competition from other drugs. Although addressing the issue of the market price for drugs seems to be one that is not controllable, there is increasing demand for drug pricing reform.2

Many believe drug prices should be linked directly to clinical benefit. In a recent article, Goldstein and colleagues proposed establishing a value-based price for necitumumab based on clinical benefit, prior to FDA approval.3 When this analysis was done, necitumumab was pending FDA approval in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine for the treatment of squamous carcinoma of the lung. Using clinical data from the SQUIRE trial on which FDA approval was based, the addition of necitumumab to the chemotherapy regimen led to an incremental survival benefit of 0.15 life-years and 0.11 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY).4 Using a Markov model to evaluate cost-effectiveness, these authors established that the price of necitumumab should be from $563 to $1,309 per cycle. Necitumumab was approved by the FDA on November 24, 2015, with the VA acquisition cost, as of May 2016, at $6,100 per cycle.

Lack of Generic Products

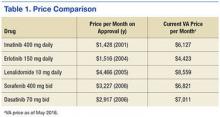

The approval of generic alternatives for targeted oncology agents should reduce the cost of treating oncology patients. However, since imatinib was approved in May 2001, no single targeted agent had become available as a generic until February 1, 2016, when generic imatinib was made available in the U.S. following approval by the FDA. Currently, generic imatinib is not used in the VA due to lack of Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) contract pricing, which leads to a generic cost that is much higher than the brand-name drug, Gleevec ($6,127 per month vs $9,472 per month for the generic). The reality is that many older agents have steadily increased in price, outpacing inflation (Table 1).5

Aging U.S. Population

Advancing age is the most common risk factor for cancer, leading to an increase in the incidence and treatment of cancer. Because many newer agents are considered easier to tolerate than are traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, clinicians have become more comfortable treating elderly patients, and geriatric oncology has become an established subspecialty within oncology.

Changing Treatment Paradigms

The use of targeted therapies is changing the paradigm from the acute treatment of cancer to chronic cancer management. Most targeted therapies are continued until disease progression or toxicity, leading to chronic, open-ended treatment. This approach is in contrast to older treatment approaches such as chemotherapy, which is often given for a limited duration followed by observation. When successful, chronic treatment with targeted agents can lead to unanticipated high costs. The following current cases at the VA San Diego Healthcare System illustrate this point:

- Renal cell carcinoma: 68-year-old man diagnosed in 2005 with a recurrence in 2012

- High-dose interleukin-2 (2 cycles); sunitinib (3.3 years); pazopanib (2 months); everolimus (2 months); sorafenib (3 months); axitinib (7 months)

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 68-year-old man started romidepsin September 22, 2010

The rate of FDA approval for oncology drugs has been accelerating rapidly in the past 15 years. Sequential therapies beyond second-line therapy are common as more agents become available. Table 2 shows FDA approval for all cancer drugs by decade.

As researchers continue to better understand the many pathways involved with the development and progression of cancer, they are beginning to combine multiple targeted agents to augment response rates, prolong survival, and reduce the potential for resistance. Recent combination regimens approved by the FDA include dabrafenib plus trametinib (January 2014), and ipilimumab plus nivolumab (October 2015), both for the treatment of melanoma. In November 2015, ixazomib was FDA approved to be used in combination with lenalidomide for multiple myeloma. Many more combination regimens are currently in clinical trials, and more combinations are expected to receive FDA approval. It is easy to see how the combination of multiple expensive agents with the prospect of prolonged therapy has the potential to increase the cost of many regimens to well over $100,000 per year.

Maintenance therapy is used to prolong PFS for patients receiving an excellent response to primary therapy. For example, VA costs for maintenance regimens include lenalidomide 10 mg daily: $8,314 for 28 days equals $216,177 for 2 years; bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 (2.6 mg) q: 2 weeks equals $60,730 for 2 years (includes waste as bortezomib 3.5-mg vials do not a contain preservative and must be discarded within 8 hours of preparation); and rituximab 800 mg q: 2 months equals $47,635 for 2 years.

Until recently, immunotherapy for cancer was limited to melanoma and renal cell carcinoma using interleukin-2 (aldesleukin) and interferon alfa. However, the immergence of new immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies, have expanded the role of immunotherapy to many other, more common, malignancies, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, head and neck cancer, and many more.

Most randomized clinical trials study drugs as second- or occasionally third-line therapy. However, many patients continue to be treated beyond the third-line setting, often without evidence-based data to support potential benefit. Patients often place value on treatments unlikely to work so as not to give up hope. These “hopeful gambles,” even with the potential of significant toxicity and decreased quality of life (QOL), are common in cancer treatment.6 In addition, oncologists often overestimate the clinical benefit when considering additional therapy in this setting.7

Influx of New Patients

Outside the VHA setting, the financial burden of cancer treatment has led to an influx of new patients transferring care to the VHA to reduce out-of-pocket expenses. Because private insurance copays for oral agents are increasing, many reaching 20% to 30%, out-of-pocket expenses for medications can reach several thousand dollars per month. Patients often change insurance plans due to changing jobs or to decrease cost, or employers may change plans to save money, which may significantly alter or discontinue coverage. Patients often request that the VA provide medication while continuing to see only their private oncologist. This practice should be discouraged because the VA, without clinical involvement, may supply drugs for inappropriate indications. In addition, VA providers writing prescriptions for medications without personally following patients may be liable for poor outcomes.

VA PBM Services

Prior to 1995, the VA was a much criticized and poorly performing health care system that had experienced significant budget cuts, forcing many veterans to seek care outside the VA. Then beginning in 1995, a remarkable transformation occurred, which modernized and improved the VA into a system that consistently outperforms the private sector in quality of care, patient safety, patient satisfaction, all at a lower cost.8 The story of the VA’s transformation has been well chronicled by Phillip Longman.9

Under the direction of VA Under Secretary for Health Kenneth Kizer, MD, MPH, VA established PBM Clinical Services to develop and maintain the National Drug Formulary, create clinical guidance documents, and manage drug costs and utilization. A recent article by Heron and Geraci examined the functions and role of the VA PBM in controlling oncology drug costs.10 The following is a brief review of several documents and VA PBM responsibilities as reviewed by Heron and Geraci.

VA National Formulary

Prior to the establishment of the VA National Formulary in 1995, each VA maintained its own formulary, which led to extreme variability in drug access across the country. When a patient accessed care at different VAMCs, it was common for the patient’s medications to be changed based on the specific facility formulary. This practice led to many potential problems, such as lack of clinical benefit and potentially increased or new toxicities, and led to extra hospital visits for monitoring and adjustment of medications.

In contrast, the VA National Formulary now offers a uniform pharmacy benefit to all veterans by reducing variation in access to drugs. In addition, using preferred agents in each drug class provides VA with additional leverage when contracting with drug suppliers to reduce prices across the entire VA system.

Many oncology agents are not included on the VA National Formulary due to cost and the potential for off-label use. However, the formulary status of oncology agents in no way limits access or the availability of any oncology drug for appropriate patients. In fact, nonformulary approval requests work as a mechanism for review to ensure that these agents are used properly in the subset of patients who are most likely to benefit.

The PBM assesses all new oncology drugs for value and potential use within the VA, as well as cost impact. Following this assessment, various clinical guidance documents may be developed that are intended to guide clinicians in the proper use of medications for veterans. All documents prepared by the PBM undergo an extensive peer review by the Medical Advisory Panel and other experts in the field.

Drug Monographs

A drug monograph is a comprehensive, evidence-based drug review that summarizes efficacy and safety based on clinical trial data published in peer-reviewed journals, abstracts, and/or FDA Medical Review transcripts. Cost-effectiveness analysis is included if available.

Criteria for Use

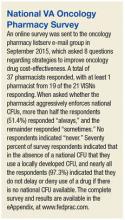

Criteria for Use (CFU) are developed for drugs considered to be at high risk for inappropriate use or with safety concerns. The purpose of the CFU is to select patients most likely to benefit from these agents by using clinical criteria, which may qualify or eliminate a patient for treatment. National CFUs are available on the national PBM website. Local CFUs are often written and shared among oncology pharmacists via the VA oncology pharmacist listserv.

Abbreviated Reviews

Similar to drug monographs, abbreviated reviews are much shorter and focus on the relevant clinical sections of the drug monograph necessary for clinical or formulary decision making.

National Acquisition Center

The National Acquisition Center (NAC) is the pharmaceutical contracting mechanism for the VA and works closely with the PBM.5 The NAC pursues significant drug price reductions for the VA based on many strategies. Public Law 102-585 ensures that certain government agencies, including the VA, receive special discounts on pharmaceuticals, which is at least a 24% discount from the nonfederal Average Manufacturer Price. This is known as the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) and/or Big 4 pricing. In addition, bulk purchases and performance-based incentive agreements can lead to substantial local discounts. By working with specific drug distribution and warehouse contractors, the NAC assures ready access to drugs for VA patients. The NAC also allows for an efficient drug inventory process, thus reducing inventory management costs.

Guidance Documents

In 2012, the VA Oncology Field Advisory Committee (FAC) created the High Cost Oncology Drug Work Group to address the impact of high-cost oncology drugs within the VA.11 This work group was composed of VA oncologists and pharmacists whose efforts resulted in 5 guidance documents designed to reduce drug costs by optimizing therapy and reducing waste: (1) Dose Rounding in Oncology; (2) Oral Anticancer Drugs Dispensing and Monitoring; (3) Oncology Drug Table: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring; (4) Chemotherapy Review Committee Process; and (5) Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs. Reviews of 2 of these documents follows.

Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs provides a decision tool to aid members of the oncology health care team in optimizing patient outcomes while attempting to obtain the greatest value from innovative therapies. When a high-cost or off-label request is made for a particular patient, using this process encourages thoughtful and evidence-based use of the drug by considering all clinical evidence in addition to the FDA-approved indication. Finally, a drug’s safety profile in relation to the indication, therapeutic goal, and specific patient characteristics and desires are integrated into a final decision to determine the appropriateness of the therapeutic intervention for the patient.

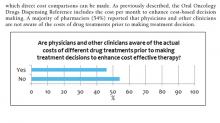

Oncology Drug Table: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring contains a list of oral oncology drugs and includes recommendations for dispensing amount, adverse effects, laboratory monitoring, formulary status, approval requirements, and monthly cost of each agent based on the current NAC pricing.5 Cost awareness is critical when comparing alternative treatment options to minimize cost when treatments with similar benefits are considered. Most VA oncologists do not have easy access to the cost of various treatments and can be surprised about how expensive many common regimens cost. The costs listed in this document are updated about every 3 months.

Conclusion

Using newer, expensive targeted oncology agents in a cost-effective manner must be a proactive, collaborative, and multidisciplinary process. Pharmacists should not be solely responsible for monitoring and controlling high-cost treatments. Well-informed, evidence-based decisions are needed to ensure expensive agents are used in the subset of patients who are most likely to benefit. Clinical tools addressing value should be used to aid in appropriate and cost-effective treatment plans using drug monographs and CFUs, VHA Guidance on Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs, and the Oral Chemotherapy Dispensing and Monitoring Reference, among other resources. Due to the subjective nature of value in medicine, agreeing on policy will have many challenges, such as how to place a value on various gains in overall survival, progression free survival, response rates, and QOL.

eAppendix

1. Bach PB. Limits on Medicare's ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):626-633.

2. Kantarjian H, Steensma D, Rius Sanjuan J, Eishaug A, Light D. High cancer drug prices in the United States: reasons and proposed solutions. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):e208-e211.

3. Goldstein DA, Chen Q, Ayer T, et al. Necitumumab in metastatic squamous cell lung cancer: establishing a value-based cost. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1293-1300.

4. Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV, et al; SQUIRE Investigators. Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):763-774.

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Acquisition Center, Pharmaceutical Catalog Search. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Acquisition Center website. http://www1.va.gov/nac/index.cfm?template=Search_Pharmaceutical_Catalog. Updated June 13, 2016. Accessed June 13, 2016.

6. Lakdawalla DN, Romley JA, Sanchez Y, Maclean JR, Penrod JR, Philipson T. How cancer patients value hope and the implications for cost-effectiveness assessments of high-cost cancer therapies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):676-682.

7. Ubel PA, Berry SR, Nadler E, et al. In a survey, marked inconsistency in how oncologists judged value of high-cost cancer drugs in relation to gains in survival. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):709-717.

8. Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12):938-945. 9. Longman P. Best Care Anywhere: Why VA Health Care Would Work for Everyone. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2012. 10. Heron BB, Geraci MC. Controlling the cost of oncology drugs within the VA: a national perspective. Fed Pract. 2015;32(suppl 1):18S-22S.

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services Intranet, Documents and Lists. https://vaww.cmopnational.va.gov/cmop/PBM/Clinical%20Guidance/Forms/AllItems.aspx. Accessed May 19, 2016.

The Cost of Oncology Drugs: A Pharmacy Perspective, Part 1, appeared in the Federal Practitioner February 2016 special issue “Best Practices in Hematology and Oncology” and can be accessed here.

Health care costs are the fastest growing financial segment of the U.S. economy. The cost of medications, especially those for treating cancer, is the leading cause of increased health care spending.1 Until recently, the discussion of the high costs of cancer treatment was rarely made public.

Part 1 of this article focused on the emerging discussion of the financial impact of high-cost drugs in the U.S. Part 2 will focus on the drivers of increasing oncology drug costs and the challenges high-cost medications pose for the VA. The article also will review the role of the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) in evaluating new oncology agents. Also presented are the clinical guidance tools designed to aid the clinician in the cost-effective use of these agents and results of a nationwide survey of VA oncology pharmacists regarding the use of cost-containment strategies.

Cost Drivers

Many factors are driving increased oncology drug costs within the VA. Although the cost of individual drugs has the largest impact on the accelerating cost of treating each patient, other clinical and social factors may play a role.

Increasing Cost of Individual Drugs

Drug pricing is not announced until after FDA approval. Oncology drugs at the high end of the cost spectrum are rarely curative and often add only weeks or months to overall survival (OS), the gold standard. Current clinical trial design often uses progression free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint, which makes the use of traditional pharmacoeconomic determinations of value difficult. In addition, many new drugs are first in class and/or have narrow indications that preclude competition from other drugs. Although addressing the issue of the market price for drugs seems to be one that is not controllable, there is increasing demand for drug pricing reform.2

Many believe drug prices should be linked directly to clinical benefit. In a recent article, Goldstein and colleagues proposed establishing a value-based price for necitumumab based on clinical benefit, prior to FDA approval.3 When this analysis was done, necitumumab was pending FDA approval in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine for the treatment of squamous carcinoma of the lung. Using clinical data from the SQUIRE trial on which FDA approval was based, the addition of necitumumab to the chemotherapy regimen led to an incremental survival benefit of 0.15 life-years and 0.11 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY).4 Using a Markov model to evaluate cost-effectiveness, these authors established that the price of necitumumab should be from $563 to $1,309 per cycle. Necitumumab was approved by the FDA on November 24, 2015, with the VA acquisition cost, as of May 2016, at $6,100 per cycle.

Lack of Generic Products

The approval of generic alternatives for targeted oncology agents should reduce the cost of treating oncology patients. However, since imatinib was approved in May 2001, no single targeted agent had become available as a generic until February 1, 2016, when generic imatinib was made available in the U.S. following approval by the FDA. Currently, generic imatinib is not used in the VA due to lack of Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) contract pricing, which leads to a generic cost that is much higher than the brand-name drug, Gleevec ($6,127 per month vs $9,472 per month for the generic). The reality is that many older agents have steadily increased in price, outpacing inflation (Table 1).5

Aging U.S. Population

Advancing age is the most common risk factor for cancer, leading to an increase in the incidence and treatment of cancer. Because many newer agents are considered easier to tolerate than are traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, clinicians have become more comfortable treating elderly patients, and geriatric oncology has become an established subspecialty within oncology.

Changing Treatment Paradigms

The use of targeted therapies is changing the paradigm from the acute treatment of cancer to chronic cancer management. Most targeted therapies are continued until disease progression or toxicity, leading to chronic, open-ended treatment. This approach is in contrast to older treatment approaches such as chemotherapy, which is often given for a limited duration followed by observation. When successful, chronic treatment with targeted agents can lead to unanticipated high costs. The following current cases at the VA San Diego Healthcare System illustrate this point:

- Renal cell carcinoma: 68-year-old man diagnosed in 2005 with a recurrence in 2012

- High-dose interleukin-2 (2 cycles); sunitinib (3.3 years); pazopanib (2 months); everolimus (2 months); sorafenib (3 months); axitinib (7 months)

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 68-year-old man started romidepsin September 22, 2010

The rate of FDA approval for oncology drugs has been accelerating rapidly in the past 15 years. Sequential therapies beyond second-line therapy are common as more agents become available. Table 2 shows FDA approval for all cancer drugs by decade.

As researchers continue to better understand the many pathways involved with the development and progression of cancer, they are beginning to combine multiple targeted agents to augment response rates, prolong survival, and reduce the potential for resistance. Recent combination regimens approved by the FDA include dabrafenib plus trametinib (January 2014), and ipilimumab plus nivolumab (October 2015), both for the treatment of melanoma. In November 2015, ixazomib was FDA approved to be used in combination with lenalidomide for multiple myeloma. Many more combination regimens are currently in clinical trials, and more combinations are expected to receive FDA approval. It is easy to see how the combination of multiple expensive agents with the prospect of prolonged therapy has the potential to increase the cost of many regimens to well over $100,000 per year.

Maintenance therapy is used to prolong PFS for patients receiving an excellent response to primary therapy. For example, VA costs for maintenance regimens include lenalidomide 10 mg daily: $8,314 for 28 days equals $216,177 for 2 years; bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 (2.6 mg) q: 2 weeks equals $60,730 for 2 years (includes waste as bortezomib 3.5-mg vials do not a contain preservative and must be discarded within 8 hours of preparation); and rituximab 800 mg q: 2 months equals $47,635 for 2 years.

Until recently, immunotherapy for cancer was limited to melanoma and renal cell carcinoma using interleukin-2 (aldesleukin) and interferon alfa. However, the immergence of new immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies, have expanded the role of immunotherapy to many other, more common, malignancies, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, head and neck cancer, and many more.

Most randomized clinical trials study drugs as second- or occasionally third-line therapy. However, many patients continue to be treated beyond the third-line setting, often without evidence-based data to support potential benefit. Patients often place value on treatments unlikely to work so as not to give up hope. These “hopeful gambles,” even with the potential of significant toxicity and decreased quality of life (QOL), are common in cancer treatment.6 In addition, oncologists often overestimate the clinical benefit when considering additional therapy in this setting.7

Influx of New Patients

Outside the VHA setting, the financial burden of cancer treatment has led to an influx of new patients transferring care to the VHA to reduce out-of-pocket expenses. Because private insurance copays for oral agents are increasing, many reaching 20% to 30%, out-of-pocket expenses for medications can reach several thousand dollars per month. Patients often change insurance plans due to changing jobs or to decrease cost, or employers may change plans to save money, which may significantly alter or discontinue coverage. Patients often request that the VA provide medication while continuing to see only their private oncologist. This practice should be discouraged because the VA, without clinical involvement, may supply drugs for inappropriate indications. In addition, VA providers writing prescriptions for medications without personally following patients may be liable for poor outcomes.

VA PBM Services

Prior to 1995, the VA was a much criticized and poorly performing health care system that had experienced significant budget cuts, forcing many veterans to seek care outside the VA. Then beginning in 1995, a remarkable transformation occurred, which modernized and improved the VA into a system that consistently outperforms the private sector in quality of care, patient safety, patient satisfaction, all at a lower cost.8 The story of the VA’s transformation has been well chronicled by Phillip Longman.9

Under the direction of VA Under Secretary for Health Kenneth Kizer, MD, MPH, VA established PBM Clinical Services to develop and maintain the National Drug Formulary, create clinical guidance documents, and manage drug costs and utilization. A recent article by Heron and Geraci examined the functions and role of the VA PBM in controlling oncology drug costs.10 The following is a brief review of several documents and VA PBM responsibilities as reviewed by Heron and Geraci.

VA National Formulary

Prior to the establishment of the VA National Formulary in 1995, each VA maintained its own formulary, which led to extreme variability in drug access across the country. When a patient accessed care at different VAMCs, it was common for the patient’s medications to be changed based on the specific facility formulary. This practice led to many potential problems, such as lack of clinical benefit and potentially increased or new toxicities, and led to extra hospital visits for monitoring and adjustment of medications.

In contrast, the VA National Formulary now offers a uniform pharmacy benefit to all veterans by reducing variation in access to drugs. In addition, using preferred agents in each drug class provides VA with additional leverage when contracting with drug suppliers to reduce prices across the entire VA system.

Many oncology agents are not included on the VA National Formulary due to cost and the potential for off-label use. However, the formulary status of oncology agents in no way limits access or the availability of any oncology drug for appropriate patients. In fact, nonformulary approval requests work as a mechanism for review to ensure that these agents are used properly in the subset of patients who are most likely to benefit.

The PBM assesses all new oncology drugs for value and potential use within the VA, as well as cost impact. Following this assessment, various clinical guidance documents may be developed that are intended to guide clinicians in the proper use of medications for veterans. All documents prepared by the PBM undergo an extensive peer review by the Medical Advisory Panel and other experts in the field.

Drug Monographs

A drug monograph is a comprehensive, evidence-based drug review that summarizes efficacy and safety based on clinical trial data published in peer-reviewed journals, abstracts, and/or FDA Medical Review transcripts. Cost-effectiveness analysis is included if available.

Criteria for Use

Criteria for Use (CFU) are developed for drugs considered to be at high risk for inappropriate use or with safety concerns. The purpose of the CFU is to select patients most likely to benefit from these agents by using clinical criteria, which may qualify or eliminate a patient for treatment. National CFUs are available on the national PBM website. Local CFUs are often written and shared among oncology pharmacists via the VA oncology pharmacist listserv.

Abbreviated Reviews

Similar to drug monographs, abbreviated reviews are much shorter and focus on the relevant clinical sections of the drug monograph necessary for clinical or formulary decision making.

National Acquisition Center

The National Acquisition Center (NAC) is the pharmaceutical contracting mechanism for the VA and works closely with the PBM.5 The NAC pursues significant drug price reductions for the VA based on many strategies. Public Law 102-585 ensures that certain government agencies, including the VA, receive special discounts on pharmaceuticals, which is at least a 24% discount from the nonfederal Average Manufacturer Price. This is known as the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) and/or Big 4 pricing. In addition, bulk purchases and performance-based incentive agreements can lead to substantial local discounts. By working with specific drug distribution and warehouse contractors, the NAC assures ready access to drugs for VA patients. The NAC also allows for an efficient drug inventory process, thus reducing inventory management costs.

Guidance Documents

In 2012, the VA Oncology Field Advisory Committee (FAC) created the High Cost Oncology Drug Work Group to address the impact of high-cost oncology drugs within the VA.11 This work group was composed of VA oncologists and pharmacists whose efforts resulted in 5 guidance documents designed to reduce drug costs by optimizing therapy and reducing waste: (1) Dose Rounding in Oncology; (2) Oral Anticancer Drugs Dispensing and Monitoring; (3) Oncology Drug Table: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring; (4) Chemotherapy Review Committee Process; and (5) Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs. Reviews of 2 of these documents follows.

Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs provides a decision tool to aid members of the oncology health care team in optimizing patient outcomes while attempting to obtain the greatest value from innovative therapies. When a high-cost or off-label request is made for a particular patient, using this process encourages thoughtful and evidence-based use of the drug by considering all clinical evidence in addition to the FDA-approved indication. Finally, a drug’s safety profile in relation to the indication, therapeutic goal, and specific patient characteristics and desires are integrated into a final decision to determine the appropriateness of the therapeutic intervention for the patient.

Oncology Drug Table: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring contains a list of oral oncology drugs and includes recommendations for dispensing amount, adverse effects, laboratory monitoring, formulary status, approval requirements, and monthly cost of each agent based on the current NAC pricing.5 Cost awareness is critical when comparing alternative treatment options to minimize cost when treatments with similar benefits are considered. Most VA oncologists do not have easy access to the cost of various treatments and can be surprised about how expensive many common regimens cost. The costs listed in this document are updated about every 3 months.

Conclusion

Using newer, expensive targeted oncology agents in a cost-effective manner must be a proactive, collaborative, and multidisciplinary process. Pharmacists should not be solely responsible for monitoring and controlling high-cost treatments. Well-informed, evidence-based decisions are needed to ensure expensive agents are used in the subset of patients who are most likely to benefit. Clinical tools addressing value should be used to aid in appropriate and cost-effective treatment plans using drug monographs and CFUs, VHA Guidance on Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs, and the Oral Chemotherapy Dispensing and Monitoring Reference, among other resources. Due to the subjective nature of value in medicine, agreeing on policy will have many challenges, such as how to place a value on various gains in overall survival, progression free survival, response rates, and QOL.

eAppendix

The Cost of Oncology Drugs: A Pharmacy Perspective, Part 1, appeared in the Federal Practitioner February 2016 special issue “Best Practices in Hematology and Oncology” and can be accessed here.

Health care costs are the fastest growing financial segment of the U.S. economy. The cost of medications, especially those for treating cancer, is the leading cause of increased health care spending.1 Until recently, the discussion of the high costs of cancer treatment was rarely made public.

Part 1 of this article focused on the emerging discussion of the financial impact of high-cost drugs in the U.S. Part 2 will focus on the drivers of increasing oncology drug costs and the challenges high-cost medications pose for the VA. The article also will review the role of the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) in evaluating new oncology agents. Also presented are the clinical guidance tools designed to aid the clinician in the cost-effective use of these agents and results of a nationwide survey of VA oncology pharmacists regarding the use of cost-containment strategies.

Cost Drivers

Many factors are driving increased oncology drug costs within the VA. Although the cost of individual drugs has the largest impact on the accelerating cost of treating each patient, other clinical and social factors may play a role.

Increasing Cost of Individual Drugs

Drug pricing is not announced until after FDA approval. Oncology drugs at the high end of the cost spectrum are rarely curative and often add only weeks or months to overall survival (OS), the gold standard. Current clinical trial design often uses progression free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint, which makes the use of traditional pharmacoeconomic determinations of value difficult. In addition, many new drugs are first in class and/or have narrow indications that preclude competition from other drugs. Although addressing the issue of the market price for drugs seems to be one that is not controllable, there is increasing demand for drug pricing reform.2

Many believe drug prices should be linked directly to clinical benefit. In a recent article, Goldstein and colleagues proposed establishing a value-based price for necitumumab based on clinical benefit, prior to FDA approval.3 When this analysis was done, necitumumab was pending FDA approval in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine for the treatment of squamous carcinoma of the lung. Using clinical data from the SQUIRE trial on which FDA approval was based, the addition of necitumumab to the chemotherapy regimen led to an incremental survival benefit of 0.15 life-years and 0.11 quality-adjusted life-years (QALY).4 Using a Markov model to evaluate cost-effectiveness, these authors established that the price of necitumumab should be from $563 to $1,309 per cycle. Necitumumab was approved by the FDA on November 24, 2015, with the VA acquisition cost, as of May 2016, at $6,100 per cycle.

Lack of Generic Products

The approval of generic alternatives for targeted oncology agents should reduce the cost of treating oncology patients. However, since imatinib was approved in May 2001, no single targeted agent had become available as a generic until February 1, 2016, when generic imatinib was made available in the U.S. following approval by the FDA. Currently, generic imatinib is not used in the VA due to lack of Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) contract pricing, which leads to a generic cost that is much higher than the brand-name drug, Gleevec ($6,127 per month vs $9,472 per month for the generic). The reality is that many older agents have steadily increased in price, outpacing inflation (Table 1).5

Aging U.S. Population

Advancing age is the most common risk factor for cancer, leading to an increase in the incidence and treatment of cancer. Because many newer agents are considered easier to tolerate than are traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, clinicians have become more comfortable treating elderly patients, and geriatric oncology has become an established subspecialty within oncology.

Changing Treatment Paradigms

The use of targeted therapies is changing the paradigm from the acute treatment of cancer to chronic cancer management. Most targeted therapies are continued until disease progression or toxicity, leading to chronic, open-ended treatment. This approach is in contrast to older treatment approaches such as chemotherapy, which is often given for a limited duration followed by observation. When successful, chronic treatment with targeted agents can lead to unanticipated high costs. The following current cases at the VA San Diego Healthcare System illustrate this point:

- Renal cell carcinoma: 68-year-old man diagnosed in 2005 with a recurrence in 2012

- High-dose interleukin-2 (2 cycles); sunitinib (3.3 years); pazopanib (2 months); everolimus (2 months); sorafenib (3 months); axitinib (7 months)

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 68-year-old man started romidepsin September 22, 2010

The rate of FDA approval for oncology drugs has been accelerating rapidly in the past 15 years. Sequential therapies beyond second-line therapy are common as more agents become available. Table 2 shows FDA approval for all cancer drugs by decade.

As researchers continue to better understand the many pathways involved with the development and progression of cancer, they are beginning to combine multiple targeted agents to augment response rates, prolong survival, and reduce the potential for resistance. Recent combination regimens approved by the FDA include dabrafenib plus trametinib (January 2014), and ipilimumab plus nivolumab (October 2015), both for the treatment of melanoma. In November 2015, ixazomib was FDA approved to be used in combination with lenalidomide for multiple myeloma. Many more combination regimens are currently in clinical trials, and more combinations are expected to receive FDA approval. It is easy to see how the combination of multiple expensive agents with the prospect of prolonged therapy has the potential to increase the cost of many regimens to well over $100,000 per year.

Maintenance therapy is used to prolong PFS for patients receiving an excellent response to primary therapy. For example, VA costs for maintenance regimens include lenalidomide 10 mg daily: $8,314 for 28 days equals $216,177 for 2 years; bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 (2.6 mg) q: 2 weeks equals $60,730 for 2 years (includes waste as bortezomib 3.5-mg vials do not a contain preservative and must be discarded within 8 hours of preparation); and rituximab 800 mg q: 2 months equals $47,635 for 2 years.

Until recently, immunotherapy for cancer was limited to melanoma and renal cell carcinoma using interleukin-2 (aldesleukin) and interferon alfa. However, the immergence of new immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies, have expanded the role of immunotherapy to many other, more common, malignancies, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, head and neck cancer, and many more.

Most randomized clinical trials study drugs as second- or occasionally third-line therapy. However, many patients continue to be treated beyond the third-line setting, often without evidence-based data to support potential benefit. Patients often place value on treatments unlikely to work so as not to give up hope. These “hopeful gambles,” even with the potential of significant toxicity and decreased quality of life (QOL), are common in cancer treatment.6 In addition, oncologists often overestimate the clinical benefit when considering additional therapy in this setting.7

Influx of New Patients

Outside the VHA setting, the financial burden of cancer treatment has led to an influx of new patients transferring care to the VHA to reduce out-of-pocket expenses. Because private insurance copays for oral agents are increasing, many reaching 20% to 30%, out-of-pocket expenses for medications can reach several thousand dollars per month. Patients often change insurance plans due to changing jobs or to decrease cost, or employers may change plans to save money, which may significantly alter or discontinue coverage. Patients often request that the VA provide medication while continuing to see only their private oncologist. This practice should be discouraged because the VA, without clinical involvement, may supply drugs for inappropriate indications. In addition, VA providers writing prescriptions for medications without personally following patients may be liable for poor outcomes.

VA PBM Services

Prior to 1995, the VA was a much criticized and poorly performing health care system that had experienced significant budget cuts, forcing many veterans to seek care outside the VA. Then beginning in 1995, a remarkable transformation occurred, which modernized and improved the VA into a system that consistently outperforms the private sector in quality of care, patient safety, patient satisfaction, all at a lower cost.8 The story of the VA’s transformation has been well chronicled by Phillip Longman.9

Under the direction of VA Under Secretary for Health Kenneth Kizer, MD, MPH, VA established PBM Clinical Services to develop and maintain the National Drug Formulary, create clinical guidance documents, and manage drug costs and utilization. A recent article by Heron and Geraci examined the functions and role of the VA PBM in controlling oncology drug costs.10 The following is a brief review of several documents and VA PBM responsibilities as reviewed by Heron and Geraci.

VA National Formulary

Prior to the establishment of the VA National Formulary in 1995, each VA maintained its own formulary, which led to extreme variability in drug access across the country. When a patient accessed care at different VAMCs, it was common for the patient’s medications to be changed based on the specific facility formulary. This practice led to many potential problems, such as lack of clinical benefit and potentially increased or new toxicities, and led to extra hospital visits for monitoring and adjustment of medications.

In contrast, the VA National Formulary now offers a uniform pharmacy benefit to all veterans by reducing variation in access to drugs. In addition, using preferred agents in each drug class provides VA with additional leverage when contracting with drug suppliers to reduce prices across the entire VA system.

Many oncology agents are not included on the VA National Formulary due to cost and the potential for off-label use. However, the formulary status of oncology agents in no way limits access or the availability of any oncology drug for appropriate patients. In fact, nonformulary approval requests work as a mechanism for review to ensure that these agents are used properly in the subset of patients who are most likely to benefit.

The PBM assesses all new oncology drugs for value and potential use within the VA, as well as cost impact. Following this assessment, various clinical guidance documents may be developed that are intended to guide clinicians in the proper use of medications for veterans. All documents prepared by the PBM undergo an extensive peer review by the Medical Advisory Panel and other experts in the field.

Drug Monographs

A drug monograph is a comprehensive, evidence-based drug review that summarizes efficacy and safety based on clinical trial data published in peer-reviewed journals, abstracts, and/or FDA Medical Review transcripts. Cost-effectiveness analysis is included if available.

Criteria for Use

Criteria for Use (CFU) are developed for drugs considered to be at high risk for inappropriate use or with safety concerns. The purpose of the CFU is to select patients most likely to benefit from these agents by using clinical criteria, which may qualify or eliminate a patient for treatment. National CFUs are available on the national PBM website. Local CFUs are often written and shared among oncology pharmacists via the VA oncology pharmacist listserv.

Abbreviated Reviews

Similar to drug monographs, abbreviated reviews are much shorter and focus on the relevant clinical sections of the drug monograph necessary for clinical or formulary decision making.

National Acquisition Center

The National Acquisition Center (NAC) is the pharmaceutical contracting mechanism for the VA and works closely with the PBM.5 The NAC pursues significant drug price reductions for the VA based on many strategies. Public Law 102-585 ensures that certain government agencies, including the VA, receive special discounts on pharmaceuticals, which is at least a 24% discount from the nonfederal Average Manufacturer Price. This is known as the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) and/or Big 4 pricing. In addition, bulk purchases and performance-based incentive agreements can lead to substantial local discounts. By working with specific drug distribution and warehouse contractors, the NAC assures ready access to drugs for VA patients. The NAC also allows for an efficient drug inventory process, thus reducing inventory management costs.

Guidance Documents

In 2012, the VA Oncology Field Advisory Committee (FAC) created the High Cost Oncology Drug Work Group to address the impact of high-cost oncology drugs within the VA.11 This work group was composed of VA oncologists and pharmacists whose efforts resulted in 5 guidance documents designed to reduce drug costs by optimizing therapy and reducing waste: (1) Dose Rounding in Oncology; (2) Oral Anticancer Drugs Dispensing and Monitoring; (3) Oncology Drug Table: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring; (4) Chemotherapy Review Committee Process; and (5) Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs. Reviews of 2 of these documents follows.

Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs provides a decision tool to aid members of the oncology health care team in optimizing patient outcomes while attempting to obtain the greatest value from innovative therapies. When a high-cost or off-label request is made for a particular patient, using this process encourages thoughtful and evidence-based use of the drug by considering all clinical evidence in addition to the FDA-approved indication. Finally, a drug’s safety profile in relation to the indication, therapeutic goal, and specific patient characteristics and desires are integrated into a final decision to determine the appropriateness of the therapeutic intervention for the patient.

Oncology Drug Table: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring contains a list of oral oncology drugs and includes recommendations for dispensing amount, adverse effects, laboratory monitoring, formulary status, approval requirements, and monthly cost of each agent based on the current NAC pricing.5 Cost awareness is critical when comparing alternative treatment options to minimize cost when treatments with similar benefits are considered. Most VA oncologists do not have easy access to the cost of various treatments and can be surprised about how expensive many common regimens cost. The costs listed in this document are updated about every 3 months.

Conclusion

Using newer, expensive targeted oncology agents in a cost-effective manner must be a proactive, collaborative, and multidisciplinary process. Pharmacists should not be solely responsible for monitoring and controlling high-cost treatments. Well-informed, evidence-based decisions are needed to ensure expensive agents are used in the subset of patients who are most likely to benefit. Clinical tools addressing value should be used to aid in appropriate and cost-effective treatment plans using drug monographs and CFUs, VHA Guidance on Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs, and the Oral Chemotherapy Dispensing and Monitoring Reference, among other resources. Due to the subjective nature of value in medicine, agreeing on policy will have many challenges, such as how to place a value on various gains in overall survival, progression free survival, response rates, and QOL.

eAppendix

1. Bach PB. Limits on Medicare's ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):626-633.

2. Kantarjian H, Steensma D, Rius Sanjuan J, Eishaug A, Light D. High cancer drug prices in the United States: reasons and proposed solutions. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):e208-e211.

3. Goldstein DA, Chen Q, Ayer T, et al. Necitumumab in metastatic squamous cell lung cancer: establishing a value-based cost. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1293-1300.

4. Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV, et al; SQUIRE Investigators. Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):763-774.

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Acquisition Center, Pharmaceutical Catalog Search. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Acquisition Center website. http://www1.va.gov/nac/index.cfm?template=Search_Pharmaceutical_Catalog. Updated June 13, 2016. Accessed June 13, 2016.

6. Lakdawalla DN, Romley JA, Sanchez Y, Maclean JR, Penrod JR, Philipson T. How cancer patients value hope and the implications for cost-effectiveness assessments of high-cost cancer therapies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):676-682.

7. Ubel PA, Berry SR, Nadler E, et al. In a survey, marked inconsistency in how oncologists judged value of high-cost cancer drugs in relation to gains in survival. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):709-717.

8. Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12):938-945. 9. Longman P. Best Care Anywhere: Why VA Health Care Would Work for Everyone. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2012. 10. Heron BB, Geraci MC. Controlling the cost of oncology drugs within the VA: a national perspective. Fed Pract. 2015;32(suppl 1):18S-22S.

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services Intranet, Documents and Lists. https://vaww.cmopnational.va.gov/cmop/PBM/Clinical%20Guidance/Forms/AllItems.aspx. Accessed May 19, 2016.

1. Bach PB. Limits on Medicare's ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):626-633.

2. Kantarjian H, Steensma D, Rius Sanjuan J, Eishaug A, Light D. High cancer drug prices in the United States: reasons and proposed solutions. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):e208-e211.

3. Goldstein DA, Chen Q, Ayer T, et al. Necitumumab in metastatic squamous cell lung cancer: establishing a value-based cost. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1293-1300.

4. Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV, et al; SQUIRE Investigators. Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):763-774.

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Acquisition Center, Pharmaceutical Catalog Search. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Acquisition Center website. http://www1.va.gov/nac/index.cfm?template=Search_Pharmaceutical_Catalog. Updated June 13, 2016. Accessed June 13, 2016.

6. Lakdawalla DN, Romley JA, Sanchez Y, Maclean JR, Penrod JR, Philipson T. How cancer patients value hope and the implications for cost-effectiveness assessments of high-cost cancer therapies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):676-682.

7. Ubel PA, Berry SR, Nadler E, et al. In a survey, marked inconsistency in how oncologists judged value of high-cost cancer drugs in relation to gains in survival. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(4):709-717.

8. Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12):938-945. 9. Longman P. Best Care Anywhere: Why VA Health Care Would Work for Everyone. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2012. 10. Heron BB, Geraci MC. Controlling the cost of oncology drugs within the VA: a national perspective. Fed Pract. 2015;32(suppl 1):18S-22S.

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services Intranet, Documents and Lists. https://vaww.cmopnational.va.gov/cmop/PBM/Clinical%20Guidance/Forms/AllItems.aspx. Accessed May 19, 2016.

The Cost of Oncology Drugs: A Pharmacy Perspective, Part I

Health care costs are the fastest growing financial segment of the U.S. economy. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimates health care spending in the U.S. will increase from $3.0 trillion in 2014 to $5.4 trillion by 2024.1 About 19.3% of the U.S. gross domestic product is consumed by health care, which is twice that of any other country in the world. It is often stated that the increasing cost of health care is the most significant financial threat to the U.S. economy. The cost of medications, including those for treating cancer, is the leading cause of increased health care spending.2

The cost of cancer care is the most rapidly increasing component of U.S. health care spending and will increase from $125 billion in 2010 to an estimated $158 billion in 2020, a 27% increase.3 Most experts agree that the current escalation of costs is unsustainable and, if left unchecked, will have a devastating effect on the quality of health care and an increasing negative financial impact on individuals, businesses, and government. However, that discussion is outside the scope of this article.

The affordability of health care has become a major concern for most Americans. During the recent U.S. financial crisis, most of the focus was on the bursting of the housing bubble, plummeting real estate prices, the loss of jobs, and the failure of large financial institutions. However, medical bills were still the leading cause of personal bankruptcies during this period. In 2007, 62% of personal bankruptcies in the U.S. were due to medical costs, and 78% of those bankruptcies involved patients who had health insurance at the beginning of their illness.4

The cost of prescription medications is causing financial difficulties for many patients, especially elderly.

Americans who have multiple chronic medical conditions and live on fixed incomes. A recently released survey by the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation found that the high cost of prescription medications, especially those to treat serious medical conditions such as cancer, is the top health concern of 77% of those Americans polled.5 In this environment, oncology providers face many challenges in their obligation to treat cancer patients in a cost-effective manner.

This article will appear in 2 parts. Part 1 will focus on the emerging discussion of the financial impact of high-cost drugs in the U.S. The drivers of increasing oncology drug costs will also be reviewed. Part 2 will focus on the challenges of high cost medications in the VA and the role the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Service has in evaluating new oncology agents. Clinical guidance tools designed to aid the clinician in the cost-effective use of these agents and results of a nationwide survey of VA oncology pharmacists regarding the use of cost-containment strategies will also be presented.

Background

When discussing the value of targeted therapies, it is useful to define both targeted therapy and value. A targeted therapy is a type of treatment using drugs or other substances to identify and attack cancer cells with less harm to normal cells, according to the National Cancer Institute. 6 Some targeted therapies block the action of certain enzymes, proteins, or other molecules involved in the growth and spread of cancer cells (the molecular target). Other types of targeted therapies help the immune system kill cancer cells or deliver toxic substances directly to cancer cells and kill them.

Targeted therapy may have fewer adverse effects (AEs) than do other types of cancer treatment. Most targeted therapies are either small molecules or monoclonal antibodies. Although imatinib, released in 2001, is the drug that coined the phrase targeted therapy, many drugs released earlier, such as rituximab, can be considered targeted therapies due to their specific, or targeted, mechanism of action.

Value is the price an object will bring in an open and competitive, or free, market as determined by the consumer. To put the definition of value in simpler terms, Warren Buffet has been quoted as saying, “Cost is what you pay, value is what you get.” The oncology market is not entirely free and open. Market price is determined by the manufacturer, entry into the market is regulated by the FDA, purchasers (like the VA and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) have only limited ability to negotiate prices, and refusing to pay for life-saving or life-prolonging medications often is not an option. As costs for oncology drugs rapidly increase, the cost-benefit ratio, or value, is being increasingly debated. When comparing the clinical benefits these agents provide with cost, the perception of value is highly subjective and can change significantly based on who is paying the bill.

Questioning High-Cost Drugs

Charles Moertel and colleagues published a landmark trial 25 years ago, which reported that treatment with fluorouracil and levamisole for 1 year decreased the death rate of patients with stage C (stage III) colon cancer by 33% following curative surgery.7 Although this trial was clinically significant, there was as much discussion about the high cost of levamisole (Ergamisol) tablets as there

was about its clinical benefit for patients.

In a 1991 letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, Rossof and colleagues questioned the high cost of the levamisole in the treatment regimen.8 Rossof and colleagues were surprised at the drug’s price on approval, about $5 for each tablet, and detailed their concerns on how this price was determined. “On the basis of the cost to a veterinarian, the calculated cost of a hypothetical 50-mg tablet should be in the range of 3 to 6 cents,” they argued. The total cost to the patient of 1 year of treament was nearly $1,200. Their conclusion was that “…the price chosen for the new American consumer is far too high and requires justification by the manufacturer.”

A reply from Janssen Pharmaceutica, the drug’s manufacturer, offered many justifications for the price.8 According to the company, Ergamisol was supplied free to 5,000 research patients prior to FDA approval. It was also given for free to indigent patients. The company also insisted that its pricing compared favorably with its competitors, such as zidovudine, octreotide, newer generation nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and antihypertension drugs. “Drug pricing includes additional expensive research, physician education, compassionate use programs, and ensuring high-quality control. Janssen scientists studied immunomodulating effect of Ergamisol for 25 years with no financial return. Drug development is high-risk, so companies must be able to derive a reasonable return on sales.”8

The cost of levamisole was $1,200 per year in 1991, and after adjustment for inflation would cost about $1,988 in 2015, or $166 per month. If these prices caused outrage in 1990, it is easy to see how current prices of well over $10,000 per month for therapies, which often render small clinical benefits, can seem outrageous by comparison.

Public Debate Over Cancer Drug Prices

In the U.S., about 1.66 million patients will be diagnosed with cancer in 2015.9 Although about 30% to 40% of these patients will be effectively cured, only 3% to 4% will be cured using pharmacotherapy (usually traditional chemotherapy) as a sole modality. Therefore, the use of oncology drugs by the vast majority of cancer patients is not to cure but to control or palliate patients with advanced cancer. It is important to note that the cost of most curative regimens is cheap compared with many medications used for advanced disease. Until a few years ago, discussion of the high costs of cancer treatment was rarely made public due to the devastating nature of cancer. However, with the rapid price increases and relatively disappointing clinical benefits of the many new drugs entering the market, the question of value can no longer be ignored. Many authors havepresented commentaries and strategies addressing the issues

surrounding the high cost of cancer drugs.10-15

It was a groundbreaking 2012 letter to the New York Times that brought the issue to public attention.16 Dr. Peter Bach and his colleagues at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center announced they would not purchase a “phenomenally expensive new cancer drug” for their patients, calling their decision a no-brainer. The drug, ziv-afilbercept (Zaltrap), was twice the price of a similar drug, bevacizumab (Avastin), but was no more efficacious in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Bach and colleagues went on to say how high drug prices are having a potentially devastating financial impact on patients and that laws protect drug manufacturers to set drug prices at what they feel the market will bear.

Considering the value of cancer treatments is now actively encouraged. To that point, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has recently published a groundbreaking paper entitled “A Conceptual Framework to Assess the Value of Cancer Treatment Options.”17 This tool, which is still in development, will allow oncologists to quantify clinical benefit, toxicity, and out-of-pocket drug costs so patients can compare treatment options with cost as a consideration.

The financial burden put on patients has become the driving force for drug cost reform. In an attempt to control their costs, third-party payers have increased the cost burden for patients by demanding larger copays and other out-of-pocket expenses for medications. It is felt that requiring patients to have more “skin in the game” would force them to make treatment decisions based on cost. Unfortunately, this approach may lead to devastating financial consequences for patients.18-20 The overwhelming emotions patients experience following the diagnosis of cancer make it difficult to focus on the financial impact of treatment recommendations. In addition, many oncologists are not comfortable, or even capable, of discussing costs so patients can make financially informed treatment decisions.14 Unfortunately for patients, “shopping for health care” has very little in common with shopping for a car, television sets, or any other commodity.

The VA Health Care System

The VA is government-sponsored health care and is therefore unique in the U.S. health care environment. The VA might be considered a form of “socialized medicine” that operates under a different economic model than do private health care systems. The treatment of VA patients for common diseases is based on nationally accepted evidence-based guidelines, which allow the best care in a cost-effective manner. For the treatment of cancer, the use of expensive therapies must be made in the context of the finite resources allocated for the treatment of all veterans within the system.

The VA provides lifelong free or minimal cost health care to eligible veterans. For veterans receiving care within the VA, out-of-pocket expenses are considerably less than for non-VA patients. Current medication copays range from free to $9 per month for all medications, regardless of acquisition cost. This is in stark contrast to the private sector, where patients must often pay large, percentage- based copays for oncology medications, which can reach several thousand dollars per month. VA patients are not subject to percentage-based copays; therefore, they are not a financial stakeholder in the treatment

decision process.

Prior to 1995, the VA was a much criticized and poorly performing health care system that had experienced significant budget cuts, forcing many veterans to lose their benefits and seek care outside the VA. Beginning in 1995 with the creation of PBM, a remarkable transformation occurred that modernized and transformed the VA into a system that consistently outperforms the private sector in quality of care, patient safety, and patient satisfaction while maintaining low overall costs. The role of the VA PBM was to develop and maintain the National Drug Formulary, create clinical guidance documents, and manage drug costs and use.

Part 2 of this article will more closely examine the high cost of cancer drugs. It will also discuss the role of VA PBM and other VA efforts to control cost

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here for the digital edition.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. National health expenditure projections 2014-2024 Table 01. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Website. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountsprojected.html. Updated July 30, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2016.

2. Bach PB. Limits of Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):626-633.

3. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128.

4. Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):741-746.

5. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Prescription drug costs remain atop the public’s national health care agenda, well ahead of Affordable Care Act revisions and repeal [press release]. Kaiser Family Foundation Website. http://kff.org/health-costs/press-release/prescription-drug-costs-remain-atop-the-publics-national-health-care-agenda-well-ahead-of-affordable-care-act-revisions-and-repeal. Published October 28, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2016.

6. National Cancer Institute (NCI). NCI dictionary of cancer terms: targeted therapy. National Cancer Institute Website. http://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?cdrid=270742. Accessed January 11, 2016.

7. Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(6):352-358.

8. Rossof AH, Philpot TR, Bunch RS, Letcher J. The high cost of levamisole for humans. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(10):701-702.

9. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

10. Nadler E, Eckert B, Neumann PJ. Do oncologists believe new cancer drugs offer good value? Oncologist. 2006;11(2):90-95.

11. Hillner BE, Smith TJ. Efficacy does not necessarily translate into cost effectiveness: a case study of the challenges associated with 21st century cancer drug pricing. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(13):2111-2113.

12. Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC. Legislating against use of cost-effectiveness information. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1495-1497.

13. Elkin EB, Bach PB. Cancer’s next frontier: addressing high and increasing costs. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1086-1087.

14. Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2060-2065.

15. Siddiqui M, Rajkumar SV. The high cost of cancer drugs and what we can do

about it. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(10):935-943.

16. Bach PB, Saltz LB, Wittes RE. In cancer care, cost matters [op-ed]. New York Times. October 14, 2012.

17. Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23): 2563-2577.

18. Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381-390.

19. Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on

survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Prac. 2014;10(5):332-338.

20. Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):145-150.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.