Patients needing emergency surgery for perforated diverticulitis saw no decrease in serious complications when treated with laparoscopic lavage, a minimally invasive procedure, than with primary resection of the colon, according to results from a randomized multicenter trial in Scandinavia.

Likelihood of reoperation also was significantly higher among patients undergoing laparoscopic lavage, and more sigmoid carcinomas were missed.

For their research, published Oct. 6 in JAMA (2015;314:1364-75), a group led by Dr. Johannes Kurt Schultz of the Akershus University Hospital in Lørenskog, Norway, and the University of Oslo sought to eliminate the selection bias that may have contributed to more favorable outcomes associated with laparoscopic lavage in observational studies.

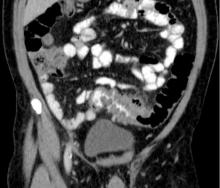

Dr. Schultz and colleagues randomized patients with suspected perforated diverticulitis from 21 centers in Sweden and Norway to laparoscopic peritoneal lavage (n = 101) or colon resection (n = 98), with the choice of open or laparoscopic approach used for resection, as well as the option of colorectal anastomosis, left to the surgeon.

The study did not use laparoscopic Hinchey staging to classify the severity of the perforation prior to treatment assignment as a way of reducing the selection bias that may have occurred in observational studies.

The preoperative randomization resulted in both groups having similar rates of feculent peritonitis and incorrect preoperative diagnoses. Patients assigned to laparoscopic lavage were treated instead with resection if they were found to have fecal peritonitis. Also, patients in both groups whose pathology required additional treatment were treated at surgeon discretion. This left 74 patients randomized to lavage who received it as assigned and 70 patients undergoing resection per assigned protocol. In the intention-to-treat analysis, 31% of patients in the lavage group and 26% of patients in the resection group saw severe postoperative complications within 90 days, a difference of 4.7% that did not reach statistical significance (95% confidence interval, −7.9% to 17%; P = .53). Severe postoperative complications were defined as any complications resulting in a reintervention requiring general anesthesia, a life-threatening organ dysfunction, or death.

Of the patients treated as assigned with lavage, about 20% (n = 15) required reoperation, compared with 6% (n = 4) in the resection arm, a difference of about 14.6% (95% CI, 3.5% to 25.6%; P =.01).

The main reasons for reoperation were secondary peritonitis in the lavage group and wound rupture in the resection group. Intra-abdominal infections were more frequent in the laparoscopic lavage group, Dr. Schultz and colleagues found.

Also in the lavage group, four carcinomas were missed, compared with two in the resection group. “Because of the relatively high rate of missed colon carcinomas in the lavage group, it was essential to perform a colonoscopy after a patient recovered from the perforation,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Although patients in the laparoscopic lavage group had significantly shorter operating times, less blood loss, and lower incidence of stoma at 3 months, the researchers concluded that, based on these results, laparoscopic lavage could not be supported in perforated diverticulitis.

Dr. Schultz and colleagues had planned to enroll about half of eligible patients at the study sites. They noted as a limitation of their study that those not enrolled had more severe disease and worse postoperative outcomes, raising the possibility that the results “may not pertain to patients with perforated diverticulitis who are very ill.”

The study was funded by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Akershus University Hospital. None of its authors reported conflicts of interest.