User login

American Heart Association (AHA): Scientific Sessions 2014

The high cost of treatment-resistant hypertension

CHICAGO– Prepare for sticker shock: Researchers have put a price tag on direct medical expenditures for treatment-resistant hypertension, and it’s a big one.

Indeed, apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (aTRH) is associated with an estimated $11.3-$17.9 billion per year in direct medical expenditures above and beyond expenditures for nonresistant hypertension in the United States, Steven M. Smith, Pharm.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is a conservative estimate based on an assumed 5% prevalence of aTRH among U.S. adults with hypertension, which may be a low figure, according to Dr. Smith of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

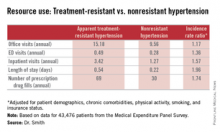

He presented an analysis of data on direct medical expenditures and health care utilization for 43,476 patients with hypertension in the nationally representative U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, of whom 1,924 met the criteria for aTRH as defined by a requirement for drugs from at least four antihypertensive medications classes in order to achieve blood pressure control.

While aTRH is known to be associated with higher rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and increased mortality relative to nonresistant hypertension, the financial costs associated with this condition haven’t previously been carefully examined.

Mean annual health care expenditures for individuals with aTRH were $20,018, more than twice the $9,814 figure for patients with nonresistant hypertension. But patients with aTRH were older, heavier, less likely to have a high income, and differed in additional ways from the much larger group with nonresistant hypertension. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these potential confounders, aTRH was associated with $2,413 in excess annual medical expenditures and $1,253 in excess total prescription expenditures, for a total of $3,647 excess total annual health care expenditures per person, compared with subjects with nonresistant hypertension.

New preventive strategies are clearly in order, Dr. Smith concluded.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without industry funding.

CHICAGO– Prepare for sticker shock: Researchers have put a price tag on direct medical expenditures for treatment-resistant hypertension, and it’s a big one.

Indeed, apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (aTRH) is associated with an estimated $11.3-$17.9 billion per year in direct medical expenditures above and beyond expenditures for nonresistant hypertension in the United States, Steven M. Smith, Pharm.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is a conservative estimate based on an assumed 5% prevalence of aTRH among U.S. adults with hypertension, which may be a low figure, according to Dr. Smith of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

He presented an analysis of data on direct medical expenditures and health care utilization for 43,476 patients with hypertension in the nationally representative U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, of whom 1,924 met the criteria for aTRH as defined by a requirement for drugs from at least four antihypertensive medications classes in order to achieve blood pressure control.

While aTRH is known to be associated with higher rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and increased mortality relative to nonresistant hypertension, the financial costs associated with this condition haven’t previously been carefully examined.

Mean annual health care expenditures for individuals with aTRH were $20,018, more than twice the $9,814 figure for patients with nonresistant hypertension. But patients with aTRH were older, heavier, less likely to have a high income, and differed in additional ways from the much larger group with nonresistant hypertension. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these potential confounders, aTRH was associated with $2,413 in excess annual medical expenditures and $1,253 in excess total prescription expenditures, for a total of $3,647 excess total annual health care expenditures per person, compared with subjects with nonresistant hypertension.

New preventive strategies are clearly in order, Dr. Smith concluded.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without industry funding.

CHICAGO– Prepare for sticker shock: Researchers have put a price tag on direct medical expenditures for treatment-resistant hypertension, and it’s a big one.

Indeed, apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (aTRH) is associated with an estimated $11.3-$17.9 billion per year in direct medical expenditures above and beyond expenditures for nonresistant hypertension in the United States, Steven M. Smith, Pharm.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is a conservative estimate based on an assumed 5% prevalence of aTRH among U.S. adults with hypertension, which may be a low figure, according to Dr. Smith of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

He presented an analysis of data on direct medical expenditures and health care utilization for 43,476 patients with hypertension in the nationally representative U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, of whom 1,924 met the criteria for aTRH as defined by a requirement for drugs from at least four antihypertensive medications classes in order to achieve blood pressure control.

While aTRH is known to be associated with higher rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and increased mortality relative to nonresistant hypertension, the financial costs associated with this condition haven’t previously been carefully examined.

Mean annual health care expenditures for individuals with aTRH were $20,018, more than twice the $9,814 figure for patients with nonresistant hypertension. But patients with aTRH were older, heavier, less likely to have a high income, and differed in additional ways from the much larger group with nonresistant hypertension. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these potential confounders, aTRH was associated with $2,413 in excess annual medical expenditures and $1,253 in excess total prescription expenditures, for a total of $3,647 excess total annual health care expenditures per person, compared with subjects with nonresistant hypertension.

New preventive strategies are clearly in order, Dr. Smith concluded.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without industry funding.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Direct medical expenditures for apparent treatment-resistant hypertension amount to up to an additional $17.9 billion annually beyond the cost associated with nonresistant hypertension.

Major finding: Patients with apparent treatment-resistant hypertension averaged twice as many office visits and nearly three times as many inpatient stays annually, compared with individuals with nonresistant hypertension. Moreover, their average hospital stay was twice as long.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on 43,476 persons with hypertension included in the U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial funding.

Promising new therapy for critical limb ischemia

CHICAGO – A single set of intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia showed safety as well as evidence of efficacy through 12 months of follow-up in the STOP-CLI trial.

“Patients treated with JVS-100 demonstrated dose-dependent improvement across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including pain, quality of life, and wound healing, with less change in macrovascular objective measures in this small study,” Dr. Melina R. Kibbe reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. JVS-100 is a nonviral plasmid encoding human stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a natural chemokine protein that promotes angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow to ischemic sites, explained Dr. Kibbe, professor and vice chair of surgical research and deputy director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

STOP-CLI was an exploratory, phase IIa, double-blind, first-in-humans study involving 48 patients with Rutherford classification 4 or 5 critical climb ischemia (CLI). All had an ankle-brachial index of 0.4 or lower, an ankle systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg or less or a toe systolic blood pressure of 50 or less, and were poor candidates for surgical revascularization. None had Buerger’s disease.

Participants were randomized to one of four study arms, and within each study arm further randomized 3:1 to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) or placebo injections. The patients received either 8 or 16 injections, each containing either 0.5 or 1.0 mg of SDF-1 or placebo. The injections, given in a single session, were placed at least 0.5 cm apart throughout the ischemic area of the affected limb.

By chance, most patients randomized to the placebo group were Rutherford 4, a category of CLI defined by rest pain, while the majority in the active treatment arms were Rutherford 5, a more severe disease manifestation characterized by ulcers. As a consequence, the SDF-1 recipients also had far larger nonhealing wounds, with an average area of 6.4 cm2, compared with 1.5 cm2, in controls.

The SDF-1 injections proved safe and were well tolerated, with no treatment-related serious adverse events and no safety signals evident in the laboratory results.

Turning to efficacy endpoints, Dr. Kibbe said self-rated visual analog scale pain scores showed clear, dose-dependent improvement over time in the SDF-1 treatment cohorts and no change in controls.

Similarly, the active treatment groups showed improved quality of life scores on all domains of the Short Form-36: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, and overall physical and mental health, the surgeon continued.

Wound area decreased significantly in the SDF-1-treated groups, with the biggest reduction – more than 8 cm2 – being noted in the three patients who received eight 1-mg injections. That was also the group with the largest wounds at baseline, with an average area of 11.4 cm2.

Of note, the major limb amputation rate was “remarkably low” for patients with such severe CLI, according to Dr. Kibbe. The rate was less than 10% over the course of 12 months, with one patient in each of the four active treatment arms having a major amputation at time intervals of 58-112 days post injection. No major limb amputations occurred in the control group.

There was a hint of improvement with SDF-1 therapy over placebo in ankle-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure, but the between-group differences were too narrow in this study to allow for any conclusions. That must await planned much larger phase III trials, according to Dr. Kibbe.

Audience members, citing the numerous failures of once-promising stem cell therapies for CLI at phase III testing over the last 10-15 years, wondered why Dr. Kibbe thinks SDF-1 will fare any better.

“This is much debated and discussed among all the people involved in these kinds of trials,” she replied. “I’d say, briefly, that a lot of it has to do with patient selection. I think when you have a mixed bag of patients in a trial, including patients with Buerger’s disease, treated in multiple different countries, using different definitions of when to amputate, all those things come into play and could account for why those phase III trials were not successful.”

“Having been involved in lots of the different gene- and cell-based therapy trials, I think one of the unique benefits of this therapy is that it kind of bridges between the two. SDF-1 basically homes your endothelial progenitor cells to the site of ischemic injury for enhanced vasculogenesis. But SDF-1 also has direct effects on endothelial cells, including stimulating proliferation and preventing apoptosis,” she added.

JVS-100 has also successfully completed a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of heart failure. In addition, the agent is being developed as a treatment for acute MI, chronic angina, and for muscle regeneration.

The STOP-CLI study was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. Dr. Kibbe reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

CHICAGO – A single set of intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia showed safety as well as evidence of efficacy through 12 months of follow-up in the STOP-CLI trial.

“Patients treated with JVS-100 demonstrated dose-dependent improvement across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including pain, quality of life, and wound healing, with less change in macrovascular objective measures in this small study,” Dr. Melina R. Kibbe reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. JVS-100 is a nonviral plasmid encoding human stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a natural chemokine protein that promotes angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow to ischemic sites, explained Dr. Kibbe, professor and vice chair of surgical research and deputy director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

STOP-CLI was an exploratory, phase IIa, double-blind, first-in-humans study involving 48 patients with Rutherford classification 4 or 5 critical climb ischemia (CLI). All had an ankle-brachial index of 0.4 or lower, an ankle systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg or less or a toe systolic blood pressure of 50 or less, and were poor candidates for surgical revascularization. None had Buerger’s disease.

Participants were randomized to one of four study arms, and within each study arm further randomized 3:1 to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) or placebo injections. The patients received either 8 or 16 injections, each containing either 0.5 or 1.0 mg of SDF-1 or placebo. The injections, given in a single session, were placed at least 0.5 cm apart throughout the ischemic area of the affected limb.

By chance, most patients randomized to the placebo group were Rutherford 4, a category of CLI defined by rest pain, while the majority in the active treatment arms were Rutherford 5, a more severe disease manifestation characterized by ulcers. As a consequence, the SDF-1 recipients also had far larger nonhealing wounds, with an average area of 6.4 cm2, compared with 1.5 cm2, in controls.

The SDF-1 injections proved safe and were well tolerated, with no treatment-related serious adverse events and no safety signals evident in the laboratory results.

Turning to efficacy endpoints, Dr. Kibbe said self-rated visual analog scale pain scores showed clear, dose-dependent improvement over time in the SDF-1 treatment cohorts and no change in controls.

Similarly, the active treatment groups showed improved quality of life scores on all domains of the Short Form-36: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, and overall physical and mental health, the surgeon continued.

Wound area decreased significantly in the SDF-1-treated groups, with the biggest reduction – more than 8 cm2 – being noted in the three patients who received eight 1-mg injections. That was also the group with the largest wounds at baseline, with an average area of 11.4 cm2.

Of note, the major limb amputation rate was “remarkably low” for patients with such severe CLI, according to Dr. Kibbe. The rate was less than 10% over the course of 12 months, with one patient in each of the four active treatment arms having a major amputation at time intervals of 58-112 days post injection. No major limb amputations occurred in the control group.

There was a hint of improvement with SDF-1 therapy over placebo in ankle-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure, but the between-group differences were too narrow in this study to allow for any conclusions. That must await planned much larger phase III trials, according to Dr. Kibbe.

Audience members, citing the numerous failures of once-promising stem cell therapies for CLI at phase III testing over the last 10-15 years, wondered why Dr. Kibbe thinks SDF-1 will fare any better.

“This is much debated and discussed among all the people involved in these kinds of trials,” she replied. “I’d say, briefly, that a lot of it has to do with patient selection. I think when you have a mixed bag of patients in a trial, including patients with Buerger’s disease, treated in multiple different countries, using different definitions of when to amputate, all those things come into play and could account for why those phase III trials were not successful.”

“Having been involved in lots of the different gene- and cell-based therapy trials, I think one of the unique benefits of this therapy is that it kind of bridges between the two. SDF-1 basically homes your endothelial progenitor cells to the site of ischemic injury for enhanced vasculogenesis. But SDF-1 also has direct effects on endothelial cells, including stimulating proliferation and preventing apoptosis,” she added.

JVS-100 has also successfully completed a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of heart failure. In addition, the agent is being developed as a treatment for acute MI, chronic angina, and for muscle regeneration.

The STOP-CLI study was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. Dr. Kibbe reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

CHICAGO – A single set of intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia showed safety as well as evidence of efficacy through 12 months of follow-up in the STOP-CLI trial.

“Patients treated with JVS-100 demonstrated dose-dependent improvement across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including pain, quality of life, and wound healing, with less change in macrovascular objective measures in this small study,” Dr. Melina R. Kibbe reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. JVS-100 is a nonviral plasmid encoding human stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a natural chemokine protein that promotes angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow to ischemic sites, explained Dr. Kibbe, professor and vice chair of surgical research and deputy director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

STOP-CLI was an exploratory, phase IIa, double-blind, first-in-humans study involving 48 patients with Rutherford classification 4 or 5 critical climb ischemia (CLI). All had an ankle-brachial index of 0.4 or lower, an ankle systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg or less or a toe systolic blood pressure of 50 or less, and were poor candidates for surgical revascularization. None had Buerger’s disease.

Participants were randomized to one of four study arms, and within each study arm further randomized 3:1 to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) or placebo injections. The patients received either 8 or 16 injections, each containing either 0.5 or 1.0 mg of SDF-1 or placebo. The injections, given in a single session, were placed at least 0.5 cm apart throughout the ischemic area of the affected limb.

By chance, most patients randomized to the placebo group were Rutherford 4, a category of CLI defined by rest pain, while the majority in the active treatment arms were Rutherford 5, a more severe disease manifestation characterized by ulcers. As a consequence, the SDF-1 recipients also had far larger nonhealing wounds, with an average area of 6.4 cm2, compared with 1.5 cm2, in controls.

The SDF-1 injections proved safe and were well tolerated, with no treatment-related serious adverse events and no safety signals evident in the laboratory results.

Turning to efficacy endpoints, Dr. Kibbe said self-rated visual analog scale pain scores showed clear, dose-dependent improvement over time in the SDF-1 treatment cohorts and no change in controls.

Similarly, the active treatment groups showed improved quality of life scores on all domains of the Short Form-36: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, and overall physical and mental health, the surgeon continued.

Wound area decreased significantly in the SDF-1-treated groups, with the biggest reduction – more than 8 cm2 – being noted in the three patients who received eight 1-mg injections. That was also the group with the largest wounds at baseline, with an average area of 11.4 cm2.

Of note, the major limb amputation rate was “remarkably low” for patients with such severe CLI, according to Dr. Kibbe. The rate was less than 10% over the course of 12 months, with one patient in each of the four active treatment arms having a major amputation at time intervals of 58-112 days post injection. No major limb amputations occurred in the control group.

There was a hint of improvement with SDF-1 therapy over placebo in ankle-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure, but the between-group differences were too narrow in this study to allow for any conclusions. That must await planned much larger phase III trials, according to Dr. Kibbe.

Audience members, citing the numerous failures of once-promising stem cell therapies for CLI at phase III testing over the last 10-15 years, wondered why Dr. Kibbe thinks SDF-1 will fare any better.

“This is much debated and discussed among all the people involved in these kinds of trials,” she replied. “I’d say, briefly, that a lot of it has to do with patient selection. I think when you have a mixed bag of patients in a trial, including patients with Buerger’s disease, treated in multiple different countries, using different definitions of when to amputate, all those things come into play and could account for why those phase III trials were not successful.”

“Having been involved in lots of the different gene- and cell-based therapy trials, I think one of the unique benefits of this therapy is that it kind of bridges between the two. SDF-1 basically homes your endothelial progenitor cells to the site of ischemic injury for enhanced vasculogenesis. But SDF-1 also has direct effects on endothelial cells, including stimulating proliferation and preventing apoptosis,” she added.

JVS-100 has also successfully completed a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of heart failure. In addition, the agent is being developed as a treatment for acute MI, chronic angina, and for muscle regeneration.

The STOP-CLI study was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. Dr. Kibbe reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia demonstrated safety and efficacy; the therapy is moving forward to phase III testing.

Major finding: The major limb amputation rate was less than 10% during 12 months of follow-up after a single dose of the novel therapy.

Data source: The STOP-CLI trial was a phase IIa, 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, six-center trial including 48 patients with critical limb ischemia.

Disclosures: The STOP-CLI trial was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

Promising new therapy for critical limb ischemia

CHICAGO– A single set of intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia showed safety as well as evidence of efficacy through 12 months of follow-up in the STOP-CLI trial.

“Patients treated with JVS-100 demonstrated dose-dependent improvement across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including pain, quality of life, and wound healing, with less change in macrovascular objective measures in this small study,” Dr. Melina R. Kibbe reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. JVS-100 is a nonviral plasmid encoding human stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a natural chemokine protein that promotes angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow to ischemic sites, explained Dr. Kibbe, professor and vice chair of surgical research and deputy director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

STOP-CLI was an exploratory, phase IIa, double-blind, first-in-humans study involving 48 patients with Rutherford classification 4 or 5 critical climb ischemia (CLI). All had an ankle-brachial index of 0.4 or lower, an ankle systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg or less or a toe systolic blood pressure of 50 or less, and were poor candidates for surgical revascularization. None had Buerger’s disease.

Participants were randomized to one of four study arms, and within each study arm further randomized 3:1 to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) or placebo injections. The patients received either 8 or 16 injections, each containing either 0.5 or 1.0 mg of SDF-1 or placebo. The injections, given in a single session, were placed at least 0.5 cm apart throughout the ischemic area of the affected limb.

By chance, most patients randomized to the placebo group were Rutherford 4, a category of CLI defined by rest pain, while the majority in the active treatment arms were Rutherford 5, a more severe disease manifestation characterized by ulcers. As a consequence, the SDF-1 recipients also had far larger nonhealing wounds, with an average area of 6.4 cm2, compared with 1.5 cm2, in controls.

The SDF-1 injections proved safe and were well tolerated, with no treatment-related serious adverse events and no safety signals evident in the laboratory results.

Turning to efficacy endpoints, Dr. Kibbe said self-rated visual analog scale pain scores showed clear, dose-dependent improvement over time in the SDF-1 treatment cohorts and no change in controls.

Similarly, the active treatment groups showed improved quality of life scores on all domains of the Short Form-36: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, and overall physical and mental health, the surgeon continued.

Wound area decreased significantly in the SDF-1-treated groups, with the biggest reduction – more than 8 cm2 – being noted in the three patients who received eight 1-mg injections. That was also the group with the largest wounds at baseline, with an average area of 11.4 cm2.

Of note, the major limb amputation rate was “remarkably low” for patients with such severe CLI, according to Dr. Kibbe. The rate was less than 10% over the course of 12 months, with one patient in each of the four active treatment arms having a major amputation at time intervals of 58-112 days post injection. No major limb amputations occurred in the control group.

There was a hint of improvement with SDF-1 therapy over placebo in ankle-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure, but the between-group differences were too narrow in this study to allow for any conclusions. That must await planned much larger phase III trials, according to Dr. Kibbe.

Audience members, citing the numerous failures of once-promising stem cell therapies for CLI at phase III testing over the last 10-15 years, wondered why Dr. Kibbe thinks SDF-1 will fare any better.

“This is much debated and discussed among all the people involved in these kinds of trials,” she replied. “I’d say, briefly, that a lot of it has to do with patient selection. I think when you have a mixed bag of patients in a trial, including patients with Buerger’s disease, treated in multiple different countries, using different definitions of when to amputate, all those things come into play and could account for why those phase III trials were not successful.”

“Having been involved in lots of the different gene- and cell-based therapy trials, I think one of the unique benefits of this therapy is that it kind of bridges between the two. SDF-1 basically homes your endothelial progenitor cells to the site of ischemic injury for enhanced vasculogenesis. But SDF-1 also has direct effects on endothelial cells, including stimulating proliferation and preventing apoptosis,” she added.

JVS-100 has also successfully completed a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of heart failure. In addition, the agent is being developed as a treatment for acute MI, chronic angina, and for muscle regeneration.

The STOP-CLI study was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. Dr. Kibbe reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

CHICAGO– A single set of intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia showed safety as well as evidence of efficacy through 12 months of follow-up in the STOP-CLI trial.

“Patients treated with JVS-100 demonstrated dose-dependent improvement across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including pain, quality of life, and wound healing, with less change in macrovascular objective measures in this small study,” Dr. Melina R. Kibbe reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. JVS-100 is a nonviral plasmid encoding human stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a natural chemokine protein that promotes angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow to ischemic sites, explained Dr. Kibbe, professor and vice chair of surgical research and deputy director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

STOP-CLI was an exploratory, phase IIa, double-blind, first-in-humans study involving 48 patients with Rutherford classification 4 or 5 critical climb ischemia (CLI). All had an ankle-brachial index of 0.4 or lower, an ankle systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg or less or a toe systolic blood pressure of 50 or less, and were poor candidates for surgical revascularization. None had Buerger’s disease.

Participants were randomized to one of four study arms, and within each study arm further randomized 3:1 to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) or placebo injections. The patients received either 8 or 16 injections, each containing either 0.5 or 1.0 mg of SDF-1 or placebo. The injections, given in a single session, were placed at least 0.5 cm apart throughout the ischemic area of the affected limb.

By chance, most patients randomized to the placebo group were Rutherford 4, a category of CLI defined by rest pain, while the majority in the active treatment arms were Rutherford 5, a more severe disease manifestation characterized by ulcers. As a consequence, the SDF-1 recipients also had far larger nonhealing wounds, with an average area of 6.4 cm2, compared with 1.5 cm2, in controls.

The SDF-1 injections proved safe and were well tolerated, with no treatment-related serious adverse events and no safety signals evident in the laboratory results.

Turning to efficacy endpoints, Dr. Kibbe said self-rated visual analog scale pain scores showed clear, dose-dependent improvement over time in the SDF-1 treatment cohorts and no change in controls.

Similarly, the active treatment groups showed improved quality of life scores on all domains of the Short Form-36: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, and overall physical and mental health, the surgeon continued.

Wound area decreased significantly in the SDF-1-treated groups, with the biggest reduction – more than 8 cm2 – being noted in the three patients who received eight 1-mg injections. That was also the group with the largest wounds at baseline, with an average area of 11.4 cm2.

Of note, the major limb amputation rate was “remarkably low” for patients with such severe CLI, according to Dr. Kibbe. The rate was less than 10% over the course of 12 months, with one patient in each of the four active treatment arms having a major amputation at time intervals of 58-112 days post injection. No major limb amputations occurred in the control group.

There was a hint of improvement with SDF-1 therapy over placebo in ankle-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure, but the between-group differences were too narrow in this study to allow for any conclusions. That must await planned much larger phase III trials, according to Dr. Kibbe.

Audience members, citing the numerous failures of once-promising stem cell therapies for CLI at phase III testing over the last 10-15 years, wondered why Dr. Kibbe thinks SDF-1 will fare any better.

“This is much debated and discussed among all the people involved in these kinds of trials,” she replied. “I’d say, briefly, that a lot of it has to do with patient selection. I think when you have a mixed bag of patients in a trial, including patients with Buerger’s disease, treated in multiple different countries, using different definitions of when to amputate, all those things come into play and could account for why those phase III trials were not successful.”

“Having been involved in lots of the different gene- and cell-based therapy trials, I think one of the unique benefits of this therapy is that it kind of bridges between the two. SDF-1 basically homes your endothelial progenitor cells to the site of ischemic injury for enhanced vasculogenesis. But SDF-1 also has direct effects on endothelial cells, including stimulating proliferation and preventing apoptosis,” she added.

JVS-100 has also successfully completed a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of heart failure. In addition, the agent is being developed as a treatment for acute MI, chronic angina, and for muscle regeneration.

The STOP-CLI study was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. Dr. Kibbe reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

CHICAGO– A single set of intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia showed safety as well as evidence of efficacy through 12 months of follow-up in the STOP-CLI trial.

“Patients treated with JVS-100 demonstrated dose-dependent improvement across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including pain, quality of life, and wound healing, with less change in macrovascular objective measures in this small study,” Dr. Melina R. Kibbe reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. JVS-100 is a nonviral plasmid encoding human stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a natural chemokine protein that promotes angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow to ischemic sites, explained Dr. Kibbe, professor and vice chair of surgical research and deputy director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

STOP-CLI was an exploratory, phase IIa, double-blind, first-in-humans study involving 48 patients with Rutherford classification 4 or 5 critical climb ischemia (CLI). All had an ankle-brachial index of 0.4 or lower, an ankle systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg or less or a toe systolic blood pressure of 50 or less, and were poor candidates for surgical revascularization. None had Buerger’s disease.

Participants were randomized to one of four study arms, and within each study arm further randomized 3:1 to stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) or placebo injections. The patients received either 8 or 16 injections, each containing either 0.5 or 1.0 mg of SDF-1 or placebo. The injections, given in a single session, were placed at least 0.5 cm apart throughout the ischemic area of the affected limb.

By chance, most patients randomized to the placebo group were Rutherford 4, a category of CLI defined by rest pain, while the majority in the active treatment arms were Rutherford 5, a more severe disease manifestation characterized by ulcers. As a consequence, the SDF-1 recipients also had far larger nonhealing wounds, with an average area of 6.4 cm2, compared with 1.5 cm2, in controls.

The SDF-1 injections proved safe and were well tolerated, with no treatment-related serious adverse events and no safety signals evident in the laboratory results.

Turning to efficacy endpoints, Dr. Kibbe said self-rated visual analog scale pain scores showed clear, dose-dependent improvement over time in the SDF-1 treatment cohorts and no change in controls.

Similarly, the active treatment groups showed improved quality of life scores on all domains of the Short Form-36: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, and overall physical and mental health, the surgeon continued.

Wound area decreased significantly in the SDF-1-treated groups, with the biggest reduction – more than 8 cm2 – being noted in the three patients who received eight 1-mg injections. That was also the group with the largest wounds at baseline, with an average area of 11.4 cm2.

Of note, the major limb amputation rate was “remarkably low” for patients with such severe CLI, according to Dr. Kibbe. The rate was less than 10% over the course of 12 months, with one patient in each of the four active treatment arms having a major amputation at time intervals of 58-112 days post injection. No major limb amputations occurred in the control group.

There was a hint of improvement with SDF-1 therapy over placebo in ankle-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure, but the between-group differences were too narrow in this study to allow for any conclusions. That must await planned much larger phase III trials, according to Dr. Kibbe.

Audience members, citing the numerous failures of once-promising stem cell therapies for CLI at phase III testing over the last 10-15 years, wondered why Dr. Kibbe thinks SDF-1 will fare any better.

“This is much debated and discussed among all the people involved in these kinds of trials,” she replied. “I’d say, briefly, that a lot of it has to do with patient selection. I think when you have a mixed bag of patients in a trial, including patients with Buerger’s disease, treated in multiple different countries, using different definitions of when to amputate, all those things come into play and could account for why those phase III trials were not successful.”

“Having been involved in lots of the different gene- and cell-based therapy trials, I think one of the unique benefits of this therapy is that it kind of bridges between the two. SDF-1 basically homes your endothelial progenitor cells to the site of ischemic injury for enhanced vasculogenesis. But SDF-1 also has direct effects on endothelial cells, including stimulating proliferation and preventing apoptosis,” she added.

JVS-100 has also successfully completed a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of heart failure. In addition, the agent is being developed as a treatment for acute MI, chronic angina, and for muscle regeneration.

The STOP-CLI study was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. Dr. Kibbe reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Intramuscular injections of stromal cell–derived factor-1 in patients with critical limb ischemia demonstrated safety and efficacy; the therapy is moving forward to phase III testing.

Major finding: The major limb amputation rate was less than 10% during 12 months of follow-up after a single dose of the novel therapy.

Data source: The STOP-CLI trial was a phase IIa, 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, six-center trial including 48 patients with critical limb ischemia.

Disclosures: The STOP-CLI trial was sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics. The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Johnson & Johnson/Cordis and Pluristem.

Zero coronary calcium means very low 10-year event risk

CHICAGO – Absence of coronary artery calcium upon imaging results in an impressively low cardiovascular event rate over the next 10 years regardless of an individual’s level of standard risk factors, according to prospective data from the MESA study.

In contrast, a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 1-10, often described as minimal CAC, nearly doubles the 10-year risk, compared with a baseline CAC score of 0.

Prior to these new 10-year data, many cardiologists considered a CAC score of 1-10 as tantamount to no CAC. Not so, Dr. Parag H. Joshi said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“A CAC of 0 is presumably identifying someone without any atherosclerosis. Just the presence of minimal calcium suggests that atherosclerosis is building up. Our data suggest that among individuals with a CAC of 1-10, current smoking, elevated non-HDL cholesterol, and particularly hypertension should be treated aggressively,” said Dr. Joshi, a clinical fellow in cardiovascular diseases and prevention at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Prior studies totaling more than 50,000 subjects with a CAC score of 0 have shown very low cardiovascular event rates over 4-5 years of follow-up. However, current cardiovascular risk estimates focus on 10-year risk. This new analysis from MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is the first study to provide prospective, 10-year events data, and those data are highly reassuring, he added.

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, when their CAC score was determined. At that time, 3,415 participants had a CAC score of 0 and 508 had a score of 1-10.

During a median 10.3 years of follow-up, 123 cardiovascular events occurred, roughly one-third of which were nonfatal acute MIs and half of which were nonfatal strokes; the remainder were cardiovascular deaths.

The event rate was 2.9/1,000 person-years in subjects with a CAC of 0 and significantly greater at 5.5/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10. However, since the cardiovascular risk factor profile of the zero CAC group was generally more favorable, Dr. Joshi and coinvestigators carried out a Cox proportional hazards analysis factoring in demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and carotid intima media thickness. The adjusted 10-year event risk in the group with a CAC score of 1-10 was 1.9-fold greater than with a CAC of 0.

The highest 10-year event rate was noted in subjects with at least three of the following four risk factors at baseline: hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The rate was 6.5/1,000 person-years in such individuals if they had a CAC of 0 and doubled at 13.1/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10.

In a multivariate Cox analysis, age, smoking, and hypertension proved to be significant predictors of cardiovascular events in the group with a CAC of 0 as well as in those with a CAC of 1-10. But there was one important difference between the two groups: While the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events associated with hypertension versus no hypertension was 2.1 in subjects with a CAC of 0, the presence of hypertension in individuals with a CAC of 1-10 increased their event risk by 10.2-fold, or nearly five times greater than the risk increase associated with hypertension in persons with a CAC of 0, Dr. Joshi observed.

Non–HDL cholesterol level was predictive of cardiovascular risk in subjects with a CAC of 1-10 but not in those with a score of 0.

When actual event rates were compared with those predicted by the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology cholesterol guidelines, the event rate in subjects with an ASCVD 10-year risk estimate of 7.5%-15% but a CAC of 0 was just 4.4%.

Audience members noted that CAC scores didn’t do a very good job of stratifying stroke risk in MESA. That’s not surprising, since the score reflects coronary but not carotid artery calcium. But it is a limitation of CAC as a predictive tool, especially in light of the fact that strokes accounted for half of all cardiovascular events in the study.

Asked where he and his coinvestigators plan to go from here, Dr. Joshi said a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal, but to date funding isn’t available. However, the observational data from MESA and other studies suggest such a trial may not even be needed.

“Certainly the guidelines do allow for CAC scoring to be used in clinical decision making,” he noted.

The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Joshi reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Absence of coronary artery calcium upon imaging results in an impressively low cardiovascular event rate over the next 10 years regardless of an individual’s level of standard risk factors, according to prospective data from the MESA study.

In contrast, a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 1-10, often described as minimal CAC, nearly doubles the 10-year risk, compared with a baseline CAC score of 0.

Prior to these new 10-year data, many cardiologists considered a CAC score of 1-10 as tantamount to no CAC. Not so, Dr. Parag H. Joshi said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“A CAC of 0 is presumably identifying someone without any atherosclerosis. Just the presence of minimal calcium suggests that atherosclerosis is building up. Our data suggest that among individuals with a CAC of 1-10, current smoking, elevated non-HDL cholesterol, and particularly hypertension should be treated aggressively,” said Dr. Joshi, a clinical fellow in cardiovascular diseases and prevention at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Prior studies totaling more than 50,000 subjects with a CAC score of 0 have shown very low cardiovascular event rates over 4-5 years of follow-up. However, current cardiovascular risk estimates focus on 10-year risk. This new analysis from MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is the first study to provide prospective, 10-year events data, and those data are highly reassuring, he added.

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, when their CAC score was determined. At that time, 3,415 participants had a CAC score of 0 and 508 had a score of 1-10.

During a median 10.3 years of follow-up, 123 cardiovascular events occurred, roughly one-third of which were nonfatal acute MIs and half of which were nonfatal strokes; the remainder were cardiovascular deaths.

The event rate was 2.9/1,000 person-years in subjects with a CAC of 0 and significantly greater at 5.5/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10. However, since the cardiovascular risk factor profile of the zero CAC group was generally more favorable, Dr. Joshi and coinvestigators carried out a Cox proportional hazards analysis factoring in demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and carotid intima media thickness. The adjusted 10-year event risk in the group with a CAC score of 1-10 was 1.9-fold greater than with a CAC of 0.

The highest 10-year event rate was noted in subjects with at least three of the following four risk factors at baseline: hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The rate was 6.5/1,000 person-years in such individuals if they had a CAC of 0 and doubled at 13.1/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10.

In a multivariate Cox analysis, age, smoking, and hypertension proved to be significant predictors of cardiovascular events in the group with a CAC of 0 as well as in those with a CAC of 1-10. But there was one important difference between the two groups: While the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events associated with hypertension versus no hypertension was 2.1 in subjects with a CAC of 0, the presence of hypertension in individuals with a CAC of 1-10 increased their event risk by 10.2-fold, or nearly five times greater than the risk increase associated with hypertension in persons with a CAC of 0, Dr. Joshi observed.

Non–HDL cholesterol level was predictive of cardiovascular risk in subjects with a CAC of 1-10 but not in those with a score of 0.

When actual event rates were compared with those predicted by the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology cholesterol guidelines, the event rate in subjects with an ASCVD 10-year risk estimate of 7.5%-15% but a CAC of 0 was just 4.4%.

Audience members noted that CAC scores didn’t do a very good job of stratifying stroke risk in MESA. That’s not surprising, since the score reflects coronary but not carotid artery calcium. But it is a limitation of CAC as a predictive tool, especially in light of the fact that strokes accounted for half of all cardiovascular events in the study.

Asked where he and his coinvestigators plan to go from here, Dr. Joshi said a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal, but to date funding isn’t available. However, the observational data from MESA and other studies suggest such a trial may not even be needed.

“Certainly the guidelines do allow for CAC scoring to be used in clinical decision making,” he noted.

The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Joshi reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Absence of coronary artery calcium upon imaging results in an impressively low cardiovascular event rate over the next 10 years regardless of an individual’s level of standard risk factors, according to prospective data from the MESA study.

In contrast, a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 1-10, often described as minimal CAC, nearly doubles the 10-year risk, compared with a baseline CAC score of 0.

Prior to these new 10-year data, many cardiologists considered a CAC score of 1-10 as tantamount to no CAC. Not so, Dr. Parag H. Joshi said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“A CAC of 0 is presumably identifying someone without any atherosclerosis. Just the presence of minimal calcium suggests that atherosclerosis is building up. Our data suggest that among individuals with a CAC of 1-10, current smoking, elevated non-HDL cholesterol, and particularly hypertension should be treated aggressively,” said Dr. Joshi, a clinical fellow in cardiovascular diseases and prevention at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Prior studies totaling more than 50,000 subjects with a CAC score of 0 have shown very low cardiovascular event rates over 4-5 years of follow-up. However, current cardiovascular risk estimates focus on 10-year risk. This new analysis from MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is the first study to provide prospective, 10-year events data, and those data are highly reassuring, he added.

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, when their CAC score was determined. At that time, 3,415 participants had a CAC score of 0 and 508 had a score of 1-10.

During a median 10.3 years of follow-up, 123 cardiovascular events occurred, roughly one-third of which were nonfatal acute MIs and half of which were nonfatal strokes; the remainder were cardiovascular deaths.

The event rate was 2.9/1,000 person-years in subjects with a CAC of 0 and significantly greater at 5.5/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10. However, since the cardiovascular risk factor profile of the zero CAC group was generally more favorable, Dr. Joshi and coinvestigators carried out a Cox proportional hazards analysis factoring in demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and carotid intima media thickness. The adjusted 10-year event risk in the group with a CAC score of 1-10 was 1.9-fold greater than with a CAC of 0.

The highest 10-year event rate was noted in subjects with at least three of the following four risk factors at baseline: hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The rate was 6.5/1,000 person-years in such individuals if they had a CAC of 0 and doubled at 13.1/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10.

In a multivariate Cox analysis, age, smoking, and hypertension proved to be significant predictors of cardiovascular events in the group with a CAC of 0 as well as in those with a CAC of 1-10. But there was one important difference between the two groups: While the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events associated with hypertension versus no hypertension was 2.1 in subjects with a CAC of 0, the presence of hypertension in individuals with a CAC of 1-10 increased their event risk by 10.2-fold, or nearly five times greater than the risk increase associated with hypertension in persons with a CAC of 0, Dr. Joshi observed.

Non–HDL cholesterol level was predictive of cardiovascular risk in subjects with a CAC of 1-10 but not in those with a score of 0.

When actual event rates were compared with those predicted by the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology cholesterol guidelines, the event rate in subjects with an ASCVD 10-year risk estimate of 7.5%-15% but a CAC of 0 was just 4.4%.

Audience members noted that CAC scores didn’t do a very good job of stratifying stroke risk in MESA. That’s not surprising, since the score reflects coronary but not carotid artery calcium. But it is a limitation of CAC as a predictive tool, especially in light of the fact that strokes accounted for half of all cardiovascular events in the study.

Asked where he and his coinvestigators plan to go from here, Dr. Joshi said a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal, but to date funding isn’t available. However, the observational data from MESA and other studies suggest such a trial may not even be needed.

“Certainly the guidelines do allow for CAC scoring to be used in clinical decision making,” he noted.

The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Joshi reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A coronary artery calcium score of 0 appears to trump the 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines.

Major finding: The actual 10-year cardiovascular event rate in subjects with a coronary artery calcium score of 0 was just 4.4% – below the guideline-recommended threshold for statin therapy– even though their predicted risk using the AHA/ACC risk estimator was 7.5%-15%.

Data source: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Disclosures: The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Transfusion linked to bad outcomes in percutaneous peripheral vascular interventions

CHICAGO – Periprocedural blood transfusion rates vary greatly among hospitals performing similar percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease, but these rates can be markedly reduced via a focused quality improvement program.

That’s been the lesson learned in Michigan, where blood transfusion rates dropped by 52% statewide at the 44 hospitals participating in the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium Vascular Intervention Collaborative (BMC2 PCI-VIC), Dr. Peter K. Henke reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

That’s good news because periprocedural blood transfusions in patients undergoing percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) are associated with startlingly high major morbidity and mortality rates. Indeed, among 18,127 patients undergoing nonhybrid percutaneous interventions for PAD in the BMC2 PCI-VIC registry, periprocedural blood transfusion was an independent predictor of a 25-fold increased risk of MI, a 12.7-fold increase in in-hospital mortality, a 6-fold increased risk of TIA/stroke, and a 49-fold increase in vascular access complications in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for patient demographics, comorbid disease states, and periprocedural medications, according to Dr. Henke, professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

That being said, he was quick to add that he believes these associations largely reflect correlation, not causality. Transfusion recipients were significantly older and sicker than nontransfused patients undergoing the same percutaneous peripheral vascular interventions. They were far more likely to have critical limb ischemia and undergo an urgent or emergent procedure. Of note, as statewide transfusion rates fell from about 6.6% to 3.2% in response to the quality improvement program, crude in-hospital mortality didn’t change significantly, again suggesting a noncausal relationship.

The quality improvement project was undertaken in response to the observation that periprocedural transfusion rates varied institutionally across the state from 0% to 14% for patients undergoing the same percutaneous interventions for PAD. That was a red flag indicating an opportunity for improved practice.

“The median nadir hemoglobin varied within a rather narrow range of 6.8-8.5 g/dL, yet the transfusion rates were quite wide ranging,” the surgeon observed.

Over a 2-year period, the BMC2 PCI-VIC quality improvement team made repeated site visits to the hospitals with the lowest transfusion rates. They performed detailed analysis of peripheral vascular procedure processes, protocols, and order sets in order to identify best practices. Those best practices were then shared at meetings with representatives of all the participating hospitals. Feedback was provided. And transfusion rates began dropping.

Analysis of the 18,000-plus patients enrolled in the registry led to identification of a specific set of risk factors for blood transfusions, most of which occurred after patients had left the catheterization lab. These risk factors included low creatinine clearance, preprocedural anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, use of warfarin, cerebrovascular disease, critical limb ischemia, and urgent or emergent procedures.

This was the largest-ever study focused on transfusion in patients undergoing endovascular procedures for PAD, according to Dr. Henke. He noted that the results are consistent with a recent report by other investigators regarding the implications of periprocedural blood transfusion in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. In more than 2.2 million patients who underwent PCI in 2009-2013, transfusion rates varied institutionally from 0% to 13%. Transfusion was associated with 4.6-fold in-hospital mortality, a 3.6-fold increase in acute MI, and a 7.7-fold increased risk of stroke (JAMA 2014;311:836-43).

Dr. Henke reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding the PAD transfusion study, which was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network.

CHICAGO – Periprocedural blood transfusion rates vary greatly among hospitals performing similar percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease, but these rates can be markedly reduced via a focused quality improvement program.

That’s been the lesson learned in Michigan, where blood transfusion rates dropped by 52% statewide at the 44 hospitals participating in the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium Vascular Intervention Collaborative (BMC2 PCI-VIC), Dr. Peter K. Henke reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

That’s good news because periprocedural blood transfusions in patients undergoing percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) are associated with startlingly high major morbidity and mortality rates. Indeed, among 18,127 patients undergoing nonhybrid percutaneous interventions for PAD in the BMC2 PCI-VIC registry, periprocedural blood transfusion was an independent predictor of a 25-fold increased risk of MI, a 12.7-fold increase in in-hospital mortality, a 6-fold increased risk of TIA/stroke, and a 49-fold increase in vascular access complications in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for patient demographics, comorbid disease states, and periprocedural medications, according to Dr. Henke, professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

That being said, he was quick to add that he believes these associations largely reflect correlation, not causality. Transfusion recipients were significantly older and sicker than nontransfused patients undergoing the same percutaneous peripheral vascular interventions. They were far more likely to have critical limb ischemia and undergo an urgent or emergent procedure. Of note, as statewide transfusion rates fell from about 6.6% to 3.2% in response to the quality improvement program, crude in-hospital mortality didn’t change significantly, again suggesting a noncausal relationship.

The quality improvement project was undertaken in response to the observation that periprocedural transfusion rates varied institutionally across the state from 0% to 14% for patients undergoing the same percutaneous interventions for PAD. That was a red flag indicating an opportunity for improved practice.

“The median nadir hemoglobin varied within a rather narrow range of 6.8-8.5 g/dL, yet the transfusion rates were quite wide ranging,” the surgeon observed.

Over a 2-year period, the BMC2 PCI-VIC quality improvement team made repeated site visits to the hospitals with the lowest transfusion rates. They performed detailed analysis of peripheral vascular procedure processes, protocols, and order sets in order to identify best practices. Those best practices were then shared at meetings with representatives of all the participating hospitals. Feedback was provided. And transfusion rates began dropping.

Analysis of the 18,000-plus patients enrolled in the registry led to identification of a specific set of risk factors for blood transfusions, most of which occurred after patients had left the catheterization lab. These risk factors included low creatinine clearance, preprocedural anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, use of warfarin, cerebrovascular disease, critical limb ischemia, and urgent or emergent procedures.

This was the largest-ever study focused on transfusion in patients undergoing endovascular procedures for PAD, according to Dr. Henke. He noted that the results are consistent with a recent report by other investigators regarding the implications of periprocedural blood transfusion in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. In more than 2.2 million patients who underwent PCI in 2009-2013, transfusion rates varied institutionally from 0% to 13%. Transfusion was associated with 4.6-fold in-hospital mortality, a 3.6-fold increase in acute MI, and a 7.7-fold increased risk of stroke (JAMA 2014;311:836-43).

Dr. Henke reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding the PAD transfusion study, which was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network.

CHICAGO – Periprocedural blood transfusion rates vary greatly among hospitals performing similar percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease, but these rates can be markedly reduced via a focused quality improvement program.

That’s been the lesson learned in Michigan, where blood transfusion rates dropped by 52% statewide at the 44 hospitals participating in the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium Vascular Intervention Collaborative (BMC2 PCI-VIC), Dr. Peter K. Henke reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

That’s good news because periprocedural blood transfusions in patients undergoing percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) are associated with startlingly high major morbidity and mortality rates. Indeed, among 18,127 patients undergoing nonhybrid percutaneous interventions for PAD in the BMC2 PCI-VIC registry, periprocedural blood transfusion was an independent predictor of a 25-fold increased risk of MI, a 12.7-fold increase in in-hospital mortality, a 6-fold increased risk of TIA/stroke, and a 49-fold increase in vascular access complications in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for patient demographics, comorbid disease states, and periprocedural medications, according to Dr. Henke, professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

That being said, he was quick to add that he believes these associations largely reflect correlation, not causality. Transfusion recipients were significantly older and sicker than nontransfused patients undergoing the same percutaneous peripheral vascular interventions. They were far more likely to have critical limb ischemia and undergo an urgent or emergent procedure. Of note, as statewide transfusion rates fell from about 6.6% to 3.2% in response to the quality improvement program, crude in-hospital mortality didn’t change significantly, again suggesting a noncausal relationship.

The quality improvement project was undertaken in response to the observation that periprocedural transfusion rates varied institutionally across the state from 0% to 14% for patients undergoing the same percutaneous interventions for PAD. That was a red flag indicating an opportunity for improved practice.

“The median nadir hemoglobin varied within a rather narrow range of 6.8-8.5 g/dL, yet the transfusion rates were quite wide ranging,” the surgeon observed.

Over a 2-year period, the BMC2 PCI-VIC quality improvement team made repeated site visits to the hospitals with the lowest transfusion rates. They performed detailed analysis of peripheral vascular procedure processes, protocols, and order sets in order to identify best practices. Those best practices were then shared at meetings with representatives of all the participating hospitals. Feedback was provided. And transfusion rates began dropping.

Analysis of the 18,000-plus patients enrolled in the registry led to identification of a specific set of risk factors for blood transfusions, most of which occurred after patients had left the catheterization lab. These risk factors included low creatinine clearance, preprocedural anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, use of warfarin, cerebrovascular disease, critical limb ischemia, and urgent or emergent procedures.

This was the largest-ever study focused on transfusion in patients undergoing endovascular procedures for PAD, according to Dr. Henke. He noted that the results are consistent with a recent report by other investigators regarding the implications of periprocedural blood transfusion in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. In more than 2.2 million patients who underwent PCI in 2009-2013, transfusion rates varied institutionally from 0% to 13%. Transfusion was associated with 4.6-fold in-hospital mortality, a 3.6-fold increase in acute MI, and a 7.7-fold increased risk of stroke (JAMA 2014;311:836-43).

Dr. Henke reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding the PAD transfusion study, which was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: High institutional blood transfusion rates in conjunction with percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease can be sharply and safely lowered through a focused quality improvement program.

Major finding: The average periprocedural transfusion rate at 44 Michigan hospitals fell from 6.6% to 3.2% in response to the performance improvement program.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of prospectively gathered data on 18,127 Michigan patients who underwent nonhybrid percutaneous interventions for peripheral arterial disease.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

How physicians are using ‘the power of zero’ in primary prevention

CHICAGO – Coronary artery calcium testing has established itself as a true “game changer” in primary cardiovascular prevention, proponents of the risk-stratification tool said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Knowing a patient’s coronary artery calcium score facilitates a more informed physician-patient discussion and shared decision making regarding whether to go on decades-long statin therapy, according to Dr. Khurram Nasir of the center for prevention and wellness research at Baptist Health Medical Center in Miami Beach.

“In our view, a much underappreciated value of coronary artery calcium testing lies in the power of zero. Roughly half of adults have a coronary artery calcium score of 0, and this results in a very low cardiovascular event rate,” the cardiologist said.

He presented an analysis of 4,758 nondiabetic participants in the prospective, population-based MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) in which he examined how they fared in terms of cardiovascular events over a median 10.3 years of follow-up. All were free of known cardiovascular disease at baseline. With the risk estimator included in the 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol management guidelines, 2,377 subjects would be recommended for high-intensity statin therapy at baseline on the basis of a 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk estimate of at least 7.5%. Another 589 participants were recommended for consideration of a moderate-intensity statin based on an estimated 10-year risk of 5%-7.4%.

Forty-one percent of MESA subjects recommended for a high-intensity statin according to the AHA/ACC risk estimator had a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 0, and their 10-year composite rate of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death was just 4.9% – well below the 7.5% threshold recommended for statin therapy. In contrast, if any CAC was present, the event rate was 10.5%.

With a relative risk reduction with statin therapy of 30%, the number needed to treat for 5 years to prevent one cardiovascular event in the group with a CAC of 0 would be 128. In the presence of any CAC, the number needed to treat fell to a far more reasonable 56, Dr. Nasir said.

Similarly, among the group recommended for consideration of statin therapy on the basis of a 10-year risk of 5%-7.4%, the actual event rate in the 57% of subjects with a CAC of 0 was just 1.5%. If any CAC was present, the event rate shot up to 7.2%. The number needed to treat in this cohort was 445 among those with a CAC of 0 and 90 with any CAC present.

“I think coronary artery calcium is a game changer in primary prevention,” Dr. Michael J. Blaha commented. “It sufficiently moves the needle to make you think differently about a patient. I’m not sure some of the other tests have sufficient evidence to say, ‘I’m going to think about not treating you if it’s negative and treating you if it’s positive,’ but coronary artery calcium has that evidence.”

In his own cardiology practice at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Dr. Blaha finds himself using CAC testing often, especially in his many statin-reluctant patients.

“I have a lot of patients who would fit under a recommendation for statin therapy under the 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol management guidelines, but who really don’t want to take medications. I know you see these patients in your practices, too. This is lifelong therapy, and they want a really good reason to take it or not to take it. If a patient is reluctant to take a statin and has a CAC score of 0, I will sometimes emphasize lifestyle therapy. It certainly redoubles my interest in lifestyle therapy. But if the CAC score is elevated, then I can make a specific case that the number needed to treat is very favorable, compared to the number needed to harm,” explained Dr. Blaha, a coinvestigator with Dr. Nasir in the MESA study.

Other situations where he finds CAC testing useful in daily practice include uncertainty as to a patient’s true risk level because the individual’s situation isn’t adequately captured by the AHA/ACC risk estimator. A patient with rheumatologic disease would be one example; another would be an individual who is neither white nor African American. He said he also utilizes CAC testing in statin-intolerant patients, where the results are useful in deciding how many different statins to try before saying “enough.”

Audience members asked what it’s going to take to get insurers to cover CAC testing for risk stratification. Dr. Blaha replied that more long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness data are coming. In the meantime, at an out-of-pocket cost of $75-$100, a lot of his statin-reluctant patients consider CAC testing a good buy.

“They say, ‘I’ll take this test to help me decide whether to take a pill for the rest of my life,’” according to Dr. Blaha.

Dr. Nasir said the evidence in support of CAC testing is now so strong that he believes physicians have an obligation to mention it as an option during the statin treatment decision discussion.

“At this moment, most patients are making their decision based on the guesstimate of their risk we are giving them using the risk calculator. If they have the ability through a $75-$100 test that costs about the same as 18 months of statin therapy to know that their true risk is not, say, 10%, but actually 5%, they’re less likely to choose therapy. Is it even ethical to withhold from our patients that there is a test out there that can reduce their estimated risk to a point that they can avoid statin therapy?” the cardiologist asked.

Dr. Nasir reported serving on an advisory board for Quest Diagnostics. Dr. Blaha reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Coronary artery calcium testing has established itself as a true “game changer” in primary cardiovascular prevention, proponents of the risk-stratification tool said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Knowing a patient’s coronary artery calcium score facilitates a more informed physician-patient discussion and shared decision making regarding whether to go on decades-long statin therapy, according to Dr. Khurram Nasir of the center for prevention and wellness research at Baptist Health Medical Center in Miami Beach.

“In our view, a much underappreciated value of coronary artery calcium testing lies in the power of zero. Roughly half of adults have a coronary artery calcium score of 0, and this results in a very low cardiovascular event rate,” the cardiologist said.

He presented an analysis of 4,758 nondiabetic participants in the prospective, population-based MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) in which he examined how they fared in terms of cardiovascular events over a median 10.3 years of follow-up. All were free of known cardiovascular disease at baseline. With the risk estimator included in the 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol management guidelines, 2,377 subjects would be recommended for high-intensity statin therapy at baseline on the basis of a 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk estimate of at least 7.5%. Another 589 participants were recommended for consideration of a moderate-intensity statin based on an estimated 10-year risk of 5%-7.4%.

Forty-one percent of MESA subjects recommended for a high-intensity statin according to the AHA/ACC risk estimator had a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 0, and their 10-year composite rate of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death was just 4.9% – well below the 7.5% threshold recommended for statin therapy. In contrast, if any CAC was present, the event rate was 10.5%.

With a relative risk reduction with statin therapy of 30%, the number needed to treat for 5 years to prevent one cardiovascular event in the group with a CAC of 0 would be 128. In the presence of any CAC, the number needed to treat fell to a far more reasonable 56, Dr. Nasir said.

Similarly, among the group recommended for consideration of statin therapy on the basis of a 10-year risk of 5%-7.4%, the actual event rate in the 57% of subjects with a CAC of 0 was just 1.5%. If any CAC was present, the event rate shot up to 7.2%. The number needed to treat in this cohort was 445 among those with a CAC of 0 and 90 with any CAC present.

“I think coronary artery calcium is a game changer in primary prevention,” Dr. Michael J. Blaha commented. “It sufficiently moves the needle to make you think differently about a patient. I’m not sure some of the other tests have sufficient evidence to say, ‘I’m going to think about not treating you if it’s negative and treating you if it’s positive,’ but coronary artery calcium has that evidence.”

In his own cardiology practice at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Dr. Blaha finds himself using CAC testing often, especially in his many statin-reluctant patients.

“I have a lot of patients who would fit under a recommendation for statin therapy under the 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol management guidelines, but who really don’t want to take medications. I know you see these patients in your practices, too. This is lifelong therapy, and they want a really good reason to take it or not to take it. If a patient is reluctant to take a statin and has a CAC score of 0, I will sometimes emphasize lifestyle therapy. It certainly redoubles my interest in lifestyle therapy. But if the CAC score is elevated, then I can make a specific case that the number needed to treat is very favorable, compared to the number needed to harm,” explained Dr. Blaha, a coinvestigator with Dr. Nasir in the MESA study.

Other situations where he finds CAC testing useful in daily practice include uncertainty as to a patient’s true risk level because the individual’s situation isn’t adequately captured by the AHA/ACC risk estimator. A patient with rheumatologic disease would be one example; another would be an individual who is neither white nor African American. He said he also utilizes CAC testing in statin-intolerant patients, where the results are useful in deciding how many different statins to try before saying “enough.”