User login

Length of Stay, Mortality Rise With Glycemic Variability

PHILADELPHIA – Glycemic variability appeared to be independently associated with increased length of stay and mortality in noncritically ill hospitalized patients, in a large retrospective study presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

"Glycemic variability" refers to oscillations of blood glucose levels around the mean. Two people can have identical hemoglobin A1c values, yet one may have far greater variability than the other and therefore be considered to have poorer control because of frequent bouts of hyper- and hypoglycemia, said Dr. Carlos E. Mendez, director of the diabetes management program at the Albany (N.Y.) Stratton VA Medical Center.

Previous studies done in critical care settings have demonstrated increased mortality in patients with high glycemic variability, independent of hypo- and hyperglycemia (Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:3008-13). Both in vitro and in vivo data suggest that "rather than hyperglycemia, glycemic variability has a more profound effect and greater production of reactive oxygen species and what we think is more reactive oxidative stress," Dr. Mendez said.

To examine this phenomenon in noncritically ill patients, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed glucose values from a total of 960 patients who were admitted to medical (81%) or surgical (19%) wards during 2008-2010 and for whom a minimum of two point-of-care blood glucose values per day had been ordered. A GSD (glucose standard deviation) value was calculated as a surrogate for glycemic variability.

The patients were typical of a VA population: They had a mean age of 69.8 years, and 95% were male. Their mean blood glucose was 181.3 mg/dL, with a mean GSD of 57.4 mg/dL. Average length of stay was 5.7 days. A mean of 4.8 glucose readings per day was performed for the group as a whole. Nearly a quarter (24%) had at least one hypoglycemic episode; about two-thirds were receiving insulin. The 90-day mortality was 11%. The majority (85%) had a diagnosis of diabetes.

Length of stay increased significantly with increasing GSD, from 3.3 days for the 166 patients with the least variability (0-30 mg/dL), to 6.5 days for the 245 patients with GSD of 61-90 mg/dL, to 7.4 days for the 39 who had glycemic variability greater than 120 mg/dL. Those increases translated to a mean 6% increase in length of stay for every 10-mg/dL increase in the GSD. The relationship remained significant for patients with and without diabetes, for medical and surgical patients, and for those who had and had not experienced hypoglycemia, Dr. Mendez said.

Mortality at 90 days also increased significantly with greater GSD, from 9% in those with the lowest variability, up to 28% for the patients with the highest variability. Here, there was a 9% increased risk of death for every 10 mg/dL of increased GSD. The mortality findings were significant for the patients with diabetes and for the medical ward patients, but didn’t reach significance for nondiabetic and surgical patients, probably because of low numbers, he said.

Prospective studies using continuous glucose monitoring would confirm these results and better elucidate factors that may influence glycemic variability in noncritically ill inpatients, he concluded.

Dr. Mendez disclosed no conflict of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – Glycemic variability appeared to be independently associated with increased length of stay and mortality in noncritically ill hospitalized patients, in a large retrospective study presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

"Glycemic variability" refers to oscillations of blood glucose levels around the mean. Two people can have identical hemoglobin A1c values, yet one may have far greater variability than the other and therefore be considered to have poorer control because of frequent bouts of hyper- and hypoglycemia, said Dr. Carlos E. Mendez, director of the diabetes management program at the Albany (N.Y.) Stratton VA Medical Center.

Previous studies done in critical care settings have demonstrated increased mortality in patients with high glycemic variability, independent of hypo- and hyperglycemia (Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:3008-13). Both in vitro and in vivo data suggest that "rather than hyperglycemia, glycemic variability has a more profound effect and greater production of reactive oxygen species and what we think is more reactive oxidative stress," Dr. Mendez said.

To examine this phenomenon in noncritically ill patients, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed glucose values from a total of 960 patients who were admitted to medical (81%) or surgical (19%) wards during 2008-2010 and for whom a minimum of two point-of-care blood glucose values per day had been ordered. A GSD (glucose standard deviation) value was calculated as a surrogate for glycemic variability.

The patients were typical of a VA population: They had a mean age of 69.8 years, and 95% were male. Their mean blood glucose was 181.3 mg/dL, with a mean GSD of 57.4 mg/dL. Average length of stay was 5.7 days. A mean of 4.8 glucose readings per day was performed for the group as a whole. Nearly a quarter (24%) had at least one hypoglycemic episode; about two-thirds were receiving insulin. The 90-day mortality was 11%. The majority (85%) had a diagnosis of diabetes.

Length of stay increased significantly with increasing GSD, from 3.3 days for the 166 patients with the least variability (0-30 mg/dL), to 6.5 days for the 245 patients with GSD of 61-90 mg/dL, to 7.4 days for the 39 who had glycemic variability greater than 120 mg/dL. Those increases translated to a mean 6% increase in length of stay for every 10-mg/dL increase in the GSD. The relationship remained significant for patients with and without diabetes, for medical and surgical patients, and for those who had and had not experienced hypoglycemia, Dr. Mendez said.

Mortality at 90 days also increased significantly with greater GSD, from 9% in those with the lowest variability, up to 28% for the patients with the highest variability. Here, there was a 9% increased risk of death for every 10 mg/dL of increased GSD. The mortality findings were significant for the patients with diabetes and for the medical ward patients, but didn’t reach significance for nondiabetic and surgical patients, probably because of low numbers, he said.

Prospective studies using continuous glucose monitoring would confirm these results and better elucidate factors that may influence glycemic variability in noncritically ill inpatients, he concluded.

Dr. Mendez disclosed no conflict of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – Glycemic variability appeared to be independently associated with increased length of stay and mortality in noncritically ill hospitalized patients, in a large retrospective study presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

"Glycemic variability" refers to oscillations of blood glucose levels around the mean. Two people can have identical hemoglobin A1c values, yet one may have far greater variability than the other and therefore be considered to have poorer control because of frequent bouts of hyper- and hypoglycemia, said Dr. Carlos E. Mendez, director of the diabetes management program at the Albany (N.Y.) Stratton VA Medical Center.

Previous studies done in critical care settings have demonstrated increased mortality in patients with high glycemic variability, independent of hypo- and hyperglycemia (Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:3008-13). Both in vitro and in vivo data suggest that "rather than hyperglycemia, glycemic variability has a more profound effect and greater production of reactive oxygen species and what we think is more reactive oxidative stress," Dr. Mendez said.

To examine this phenomenon in noncritically ill patients, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed glucose values from a total of 960 patients who were admitted to medical (81%) or surgical (19%) wards during 2008-2010 and for whom a minimum of two point-of-care blood glucose values per day had been ordered. A GSD (glucose standard deviation) value was calculated as a surrogate for glycemic variability.

The patients were typical of a VA population: They had a mean age of 69.8 years, and 95% were male. Their mean blood glucose was 181.3 mg/dL, with a mean GSD of 57.4 mg/dL. Average length of stay was 5.7 days. A mean of 4.8 glucose readings per day was performed for the group as a whole. Nearly a quarter (24%) had at least one hypoglycemic episode; about two-thirds were receiving insulin. The 90-day mortality was 11%. The majority (85%) had a diagnosis of diabetes.

Length of stay increased significantly with increasing GSD, from 3.3 days for the 166 patients with the least variability (0-30 mg/dL), to 6.5 days for the 245 patients with GSD of 61-90 mg/dL, to 7.4 days for the 39 who had glycemic variability greater than 120 mg/dL. Those increases translated to a mean 6% increase in length of stay for every 10-mg/dL increase in the GSD. The relationship remained significant for patients with and without diabetes, for medical and surgical patients, and for those who had and had not experienced hypoglycemia, Dr. Mendez said.

Mortality at 90 days also increased significantly with greater GSD, from 9% in those with the lowest variability, up to 28% for the patients with the highest variability. Here, there was a 9% increased risk of death for every 10 mg/dL of increased GSD. The mortality findings were significant for the patients with diabetes and for the medical ward patients, but didn’t reach significance for nondiabetic and surgical patients, probably because of low numbers, he said.

Prospective studies using continuous glucose monitoring would confirm these results and better elucidate factors that may influence glycemic variability in noncritically ill inpatients, he concluded.

Dr. Mendez disclosed no conflict of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Length of stay increased by 6% and 90-day mortality by 9% for every 10 mg/dL increase in glucose standard deviation.

Data Source: The data come from a retrospective analysis of 960 noncritically ill patients who were admitted to medical or surgical wards in a VA hospital during 2008-2010.

Disclosures: Dr. Mendez disclosed no conflict of interest.

Pancreas-Sparing GK Activator Lowers Glucose Without Hypoglycemia

PHILADELPHIA – An investigational glucokinase activator lowered glucose levels without producing hypoglycemia in a 2-week, phase IIa study of 60 patients with type 2 diabetes.

The enzyme glucokinase (GK) is involved in glucose homeostasis via control of both pancreatic insulin secretion and glucose disposal in the liver. The compound GKM-001, under development by Advinus Therapeutics, differs from other investigational GK activators in that it specifically targets the liver and avoids the pancreas, thereby eliminating the risk for hypoglycemia, Rashmi H. Barbhaiya, Ph.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In a multiple ascending dose study, 60 patients were washed out of their prior medications, then randomized either to doses of 25, 50, 200, 600, or 1,000 mg or to placebo.

Compared with baseline, there were dose-dependent reductions in the 24-hour glucose area under the curve. At day 14, the percent reductions were 9% with 25 mg, 14% with 50 mg, 15% with 200 mg, 17% with 600 mg, and 20% with 1,000 mg, while the placebo group had a 2% increase. Significant reductions were also seen in fasting glucose levels, ranging from 23 to 46 mg/dL, reported Dr. Barbhaiya, CEO and managing director of Advinus, which is based in Bangalore, India.

No hypoglycemia was seen with any of the doses following 12 hours of overnight fasting and 2 hours of postdose fasting, he said.

Neither oral glucose tolerance tests nor dinnertime mixed-meal tolerance tests on days 1 and 14 showed any changes in C-peptide area under the curve, providing further evidence that GKM-001 is not interacting with the pancreas and that its glucose-lowering action is not due to increased insulin levels, he said.

There were also no changes in levels of plasma triglycerides, aspartate transaminase, or alanine aminotransferase.

The company will soon be initiating a phase IIb study of GKM-001 that will assess its impact on hemoglobin A1c levels when used in combination with metformin, he said.

The study was funded by Advinus Therapeutics. Dr. Barbhaiya is a cofounder and a shareholder of the company.

PHILADELPHIA – An investigational glucokinase activator lowered glucose levels without producing hypoglycemia in a 2-week, phase IIa study of 60 patients with type 2 diabetes.

The enzyme glucokinase (GK) is involved in glucose homeostasis via control of both pancreatic insulin secretion and glucose disposal in the liver. The compound GKM-001, under development by Advinus Therapeutics, differs from other investigational GK activators in that it specifically targets the liver and avoids the pancreas, thereby eliminating the risk for hypoglycemia, Rashmi H. Barbhaiya, Ph.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In a multiple ascending dose study, 60 patients were washed out of their prior medications, then randomized either to doses of 25, 50, 200, 600, or 1,000 mg or to placebo.

Compared with baseline, there were dose-dependent reductions in the 24-hour glucose area under the curve. At day 14, the percent reductions were 9% with 25 mg, 14% with 50 mg, 15% with 200 mg, 17% with 600 mg, and 20% with 1,000 mg, while the placebo group had a 2% increase. Significant reductions were also seen in fasting glucose levels, ranging from 23 to 46 mg/dL, reported Dr. Barbhaiya, CEO and managing director of Advinus, which is based in Bangalore, India.

No hypoglycemia was seen with any of the doses following 12 hours of overnight fasting and 2 hours of postdose fasting, he said.

Neither oral glucose tolerance tests nor dinnertime mixed-meal tolerance tests on days 1 and 14 showed any changes in C-peptide area under the curve, providing further evidence that GKM-001 is not interacting with the pancreas and that its glucose-lowering action is not due to increased insulin levels, he said.

There were also no changes in levels of plasma triglycerides, aspartate transaminase, or alanine aminotransferase.

The company will soon be initiating a phase IIb study of GKM-001 that will assess its impact on hemoglobin A1c levels when used in combination with metformin, he said.

The study was funded by Advinus Therapeutics. Dr. Barbhaiya is a cofounder and a shareholder of the company.

PHILADELPHIA – An investigational glucokinase activator lowered glucose levels without producing hypoglycemia in a 2-week, phase IIa study of 60 patients with type 2 diabetes.

The enzyme glucokinase (GK) is involved in glucose homeostasis via control of both pancreatic insulin secretion and glucose disposal in the liver. The compound GKM-001, under development by Advinus Therapeutics, differs from other investigational GK activators in that it specifically targets the liver and avoids the pancreas, thereby eliminating the risk for hypoglycemia, Rashmi H. Barbhaiya, Ph.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In a multiple ascending dose study, 60 patients were washed out of their prior medications, then randomized either to doses of 25, 50, 200, 600, or 1,000 mg or to placebo.

Compared with baseline, there were dose-dependent reductions in the 24-hour glucose area under the curve. At day 14, the percent reductions were 9% with 25 mg, 14% with 50 mg, 15% with 200 mg, 17% with 600 mg, and 20% with 1,000 mg, while the placebo group had a 2% increase. Significant reductions were also seen in fasting glucose levels, ranging from 23 to 46 mg/dL, reported Dr. Barbhaiya, CEO and managing director of Advinus, which is based in Bangalore, India.

No hypoglycemia was seen with any of the doses following 12 hours of overnight fasting and 2 hours of postdose fasting, he said.

Neither oral glucose tolerance tests nor dinnertime mixed-meal tolerance tests on days 1 and 14 showed any changes in C-peptide area under the curve, providing further evidence that GKM-001 is not interacting with the pancreas and that its glucose-lowering action is not due to increased insulin levels, he said.

There were also no changes in levels of plasma triglycerides, aspartate transaminase, or alanine aminotransferase.

The company will soon be initiating a phase IIb study of GKM-001 that will assess its impact on hemoglobin A1c levels when used in combination with metformin, he said.

The study was funded by Advinus Therapeutics. Dr. Barbhaiya is a cofounder and a shareholder of the company.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: At day 14, the percent reductions in 24-hour glucose profiles were 9% with 25 mg, 14% with 50 mg, 15% with 200 mg, 17% with 600 mg, and 20% with 1,000 mg, while the placebo group had a 2% increase. No hypoglycemia was seen at any time with any dose.

Data Source: This was a placebo-controlled ascending dose study of 60 patients with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Advinus Therapeutics. Dr. Barbhaiya is a cofounder and a shareholder of the company.

Abatacept Delays Beta-Cell Loss in Type 1 Diabetes

PHILADELPHIA – Previous costimulation with abatacept for 24 months was associated with a continued slowing of the decline in beta-cell function 1 year after discontinuation in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes.

The findings suggest that abatacept might be useful in prevention studies in individuals at high risk of type 1 diabetes, or as one component in studies that use a combination of different strategies, said Dr. Tihamer Orban, principal investigator in the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet, through which the study was conducted.

Abatacept, marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb as Orencia, is a costimulation modulator that was approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The biologic blocks the process of T-lymphocyte activation that drives the autoimmune destruction of beta-cells leading to type 1 diabetes, according to Dr. Orban.

The current data constitute a follow-up to a randomized, double-masked trial that included 112 patients, aged 6-36 years (mean, 14 years), who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the previous 100 days. The administration of 27 intravenous infusions of abatacept over 2 years in 77 patients was associated with a 59% higher adjusted C-peptide AUC (area under the curve), compared with the 35 patients who received placebo infusions. The difference (0.378 nmol/L with abatacept vs. 0.238 nmol/L with placebo) was significant. Hemoglobin A1c was also significantly lower in the abatacept patients, with no difference in insulin use (Lancet 2011;378:412-9).

However, despite continued administration of abatacept over 24 months, the decrease in beta-cell function with abatacept was parallel to that with placebo after 6 months of treatment, causing the investigators to speculate that T-cell activation lessens with time.

The study remained double-blinded at 36 months. At that point, the mean adjusted 2-hour C-peptide AUC was 0.215 nmol/L for the 64 abatacept patients in whom it was measured, compared with 0.135 nmol/L for the 29 remaining placebo patients. The difference was still significant, said Dr. Orban, who is also an investigator in the section on immunobiology at the Joslin Diabetes Center and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Still, the major effect appeared to be within the first year of the treatment phase, and the two groups remained relatively parallel thereafter. This suggests that the drug may only be actively blocking T-cell activation around the time of diagnosis, he noted.

HbA1c was significantly lower in the abatacept-treated patients, with no difference in insulin use. In all, abatacept treatment resulted in an average 9.5 months’ delay of loss in beta-cell function, compared with placebo, Dr. Orban said.

"It seems that we may not need a full 2 years of treatment to achieve this effect. It’s very logical to try a shorter course of the drug and see if a similar effect can be achieved," Dr. Orban commented.

This study was sponsored by the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group, a clinical trials network funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Orban is founder and CEO of Orban Biotech LLC.

PHILADELPHIA – Previous costimulation with abatacept for 24 months was associated with a continued slowing of the decline in beta-cell function 1 year after discontinuation in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes.

The findings suggest that abatacept might be useful in prevention studies in individuals at high risk of type 1 diabetes, or as one component in studies that use a combination of different strategies, said Dr. Tihamer Orban, principal investigator in the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet, through which the study was conducted.

Abatacept, marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb as Orencia, is a costimulation modulator that was approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The biologic blocks the process of T-lymphocyte activation that drives the autoimmune destruction of beta-cells leading to type 1 diabetes, according to Dr. Orban.

The current data constitute a follow-up to a randomized, double-masked trial that included 112 patients, aged 6-36 years (mean, 14 years), who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the previous 100 days. The administration of 27 intravenous infusions of abatacept over 2 years in 77 patients was associated with a 59% higher adjusted C-peptide AUC (area under the curve), compared with the 35 patients who received placebo infusions. The difference (0.378 nmol/L with abatacept vs. 0.238 nmol/L with placebo) was significant. Hemoglobin A1c was also significantly lower in the abatacept patients, with no difference in insulin use (Lancet 2011;378:412-9).

However, despite continued administration of abatacept over 24 months, the decrease in beta-cell function with abatacept was parallel to that with placebo after 6 months of treatment, causing the investigators to speculate that T-cell activation lessens with time.

The study remained double-blinded at 36 months. At that point, the mean adjusted 2-hour C-peptide AUC was 0.215 nmol/L for the 64 abatacept patients in whom it was measured, compared with 0.135 nmol/L for the 29 remaining placebo patients. The difference was still significant, said Dr. Orban, who is also an investigator in the section on immunobiology at the Joslin Diabetes Center and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Still, the major effect appeared to be within the first year of the treatment phase, and the two groups remained relatively parallel thereafter. This suggests that the drug may only be actively blocking T-cell activation around the time of diagnosis, he noted.

HbA1c was significantly lower in the abatacept-treated patients, with no difference in insulin use. In all, abatacept treatment resulted in an average 9.5 months’ delay of loss in beta-cell function, compared with placebo, Dr. Orban said.

"It seems that we may not need a full 2 years of treatment to achieve this effect. It’s very logical to try a shorter course of the drug and see if a similar effect can be achieved," Dr. Orban commented.

This study was sponsored by the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group, a clinical trials network funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Orban is founder and CEO of Orban Biotech LLC.

PHILADELPHIA – Previous costimulation with abatacept for 24 months was associated with a continued slowing of the decline in beta-cell function 1 year after discontinuation in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes.

The findings suggest that abatacept might be useful in prevention studies in individuals at high risk of type 1 diabetes, or as one component in studies that use a combination of different strategies, said Dr. Tihamer Orban, principal investigator in the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet, through which the study was conducted.

Abatacept, marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb as Orencia, is a costimulation modulator that was approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The biologic blocks the process of T-lymphocyte activation that drives the autoimmune destruction of beta-cells leading to type 1 diabetes, according to Dr. Orban.

The current data constitute a follow-up to a randomized, double-masked trial that included 112 patients, aged 6-36 years (mean, 14 years), who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the previous 100 days. The administration of 27 intravenous infusions of abatacept over 2 years in 77 patients was associated with a 59% higher adjusted C-peptide AUC (area under the curve), compared with the 35 patients who received placebo infusions. The difference (0.378 nmol/L with abatacept vs. 0.238 nmol/L with placebo) was significant. Hemoglobin A1c was also significantly lower in the abatacept patients, with no difference in insulin use (Lancet 2011;378:412-9).

However, despite continued administration of abatacept over 24 months, the decrease in beta-cell function with abatacept was parallel to that with placebo after 6 months of treatment, causing the investigators to speculate that T-cell activation lessens with time.

The study remained double-blinded at 36 months. At that point, the mean adjusted 2-hour C-peptide AUC was 0.215 nmol/L for the 64 abatacept patients in whom it was measured, compared with 0.135 nmol/L for the 29 remaining placebo patients. The difference was still significant, said Dr. Orban, who is also an investigator in the section on immunobiology at the Joslin Diabetes Center and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Still, the major effect appeared to be within the first year of the treatment phase, and the two groups remained relatively parallel thereafter. This suggests that the drug may only be actively blocking T-cell activation around the time of diagnosis, he noted.

HbA1c was significantly lower in the abatacept-treated patients, with no difference in insulin use. In all, abatacept treatment resulted in an average 9.5 months’ delay of loss in beta-cell function, compared with placebo, Dr. Orban said.

"It seems that we may not need a full 2 years of treatment to achieve this effect. It’s very logical to try a shorter course of the drug and see if a similar effect can be achieved," Dr. Orban commented.

This study was sponsored by the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group, a clinical trials network funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Orban is founder and CEO of Orban Biotech LLC.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: At 36 months, the mean adjusted 2-hour C-peptide AUC was 0.215 nmol/L for the 64 abatacept patients in whom it was measured, compared with 0.135 nmol/L for the 29 remaining placebo patients, a significant difference.

Data Source: Data are from a 1-year follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial of abatacept vs. placebo infusions in 112 recently diagnosed patients with type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group, a clinical trials network funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Orban is founder and CEO of Orban Biotech LLC.

Glargine, Liraglutide Neck and Neck, Except on Cost

PHILADELPHIA – Daily glargine use among patients with type 2 diabetes produced similar clinical outcomes to those of patients using liraglutide, but with lower associated costs, according to a retrospective analysis of real-world use that was presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

When liraglutide or glargine was added to a combined metformin-plus-sulfonylurea therapy in a previous phase III trial, liraglutide demonstrated a greater reduction in hemoglobin A1c than did glargine (Diabetologia 2009;52:2046-55).

To date, however, no real-world comparative data have been published comparing use of injectable therapy with insulin glargine vs. the glucagonlike peptide–1 agonist liraglutide among patients with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Philip Levin, director of the diabetes center at Mercy Medical Center, Baltimore.

Administrative claims data were analyzed from a managed care database comprising about 50 U.S. health care plans and 107 million patients. Of those, investigators identified 967 adults who had type 2 diabetes and had initiated injectable pen therapy with either glargine (n = 557) or liraglutide (n = 410) between January and June 2010. All patients who had baseline HbA1c levels less than 7% were excluded, because it’s possible that they were started on liraglutide for weight loss rather than glucose control, Dr. Levin noted.

Because there were significant differences between the two groups at baseline – glargine initiators were older, sicker, less obese, and more likely to be male, and had higher HbA1c levels, among other differences – the 336 eligible patients were propensity matched to make the two groups more comparable. After that was done, the 168 glargine and 168 liraglutide patients did not differ significantly in sex (46% of glargine and 44% of liraglutide patients were women), age (53 years for both groups), mean Charlson comorbidity index (0.29 and 0.36, respectively), or other baseline characteristics.

The group taking glargine stayed on therapy significantly longer than did those on liraglutide (279 vs. 257 day).

Reductions in HbA1c from baseline did not differ significantly between the glargine and liraglutide groups, decreasing from 8.96% to 7.94% at 1 year with glargine, and from 8.76% to 7.81% with liraglutide (reductions of 1.02 and 0.95 percentage points, respectively). The average dose for glargine was 27.4 U/day, and for liraglutide was 1.16 mg/day.

Hypoglycemia was more common with glargine (7.7% vs. 4.7%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. Hypoglycemia requiring emergency department or inpatient treatment occurred in just 1.1% of both groups.

Health care costs were significantly lower with glargine. Study drug costs were $1,198 for glargine vs. $2,784 for liraglutide; diabetes-related drug costs were $2,958 vs. $3,988, respectively; and total diabetes-related costs were $5,653 vs. $7,976. Each of those differences was statistically significant, Dr. Levin said.

These findings will be further explored by the planned INITIATOR study, a large-scale hybrid prospective/retrospective real-world study, he noted.

The study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Levin disclosed that he is on the advisory panel for that company, as well as for Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide. He also consults for, receives research support from, or is on the speakers bureau for a long list of other manufacturers of diabetes-related products.

PHILADELPHIA – Daily glargine use among patients with type 2 diabetes produced similar clinical outcomes to those of patients using liraglutide, but with lower associated costs, according to a retrospective analysis of real-world use that was presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

When liraglutide or glargine was added to a combined metformin-plus-sulfonylurea therapy in a previous phase III trial, liraglutide demonstrated a greater reduction in hemoglobin A1c than did glargine (Diabetologia 2009;52:2046-55).

To date, however, no real-world comparative data have been published comparing use of injectable therapy with insulin glargine vs. the glucagonlike peptide–1 agonist liraglutide among patients with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Philip Levin, director of the diabetes center at Mercy Medical Center, Baltimore.

Administrative claims data were analyzed from a managed care database comprising about 50 U.S. health care plans and 107 million patients. Of those, investigators identified 967 adults who had type 2 diabetes and had initiated injectable pen therapy with either glargine (n = 557) or liraglutide (n = 410) between January and June 2010. All patients who had baseline HbA1c levels less than 7% were excluded, because it’s possible that they were started on liraglutide for weight loss rather than glucose control, Dr. Levin noted.

Because there were significant differences between the two groups at baseline – glargine initiators were older, sicker, less obese, and more likely to be male, and had higher HbA1c levels, among other differences – the 336 eligible patients were propensity matched to make the two groups more comparable. After that was done, the 168 glargine and 168 liraglutide patients did not differ significantly in sex (46% of glargine and 44% of liraglutide patients were women), age (53 years for both groups), mean Charlson comorbidity index (0.29 and 0.36, respectively), or other baseline characteristics.

The group taking glargine stayed on therapy significantly longer than did those on liraglutide (279 vs. 257 day).

Reductions in HbA1c from baseline did not differ significantly between the glargine and liraglutide groups, decreasing from 8.96% to 7.94% at 1 year with glargine, and from 8.76% to 7.81% with liraglutide (reductions of 1.02 and 0.95 percentage points, respectively). The average dose for glargine was 27.4 U/day, and for liraglutide was 1.16 mg/day.

Hypoglycemia was more common with glargine (7.7% vs. 4.7%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. Hypoglycemia requiring emergency department or inpatient treatment occurred in just 1.1% of both groups.

Health care costs were significantly lower with glargine. Study drug costs were $1,198 for glargine vs. $2,784 for liraglutide; diabetes-related drug costs were $2,958 vs. $3,988, respectively; and total diabetes-related costs were $5,653 vs. $7,976. Each of those differences was statistically significant, Dr. Levin said.

These findings will be further explored by the planned INITIATOR study, a large-scale hybrid prospective/retrospective real-world study, he noted.

The study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Levin disclosed that he is on the advisory panel for that company, as well as for Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide. He also consults for, receives research support from, or is on the speakers bureau for a long list of other manufacturers of diabetes-related products.

PHILADELPHIA – Daily glargine use among patients with type 2 diabetes produced similar clinical outcomes to those of patients using liraglutide, but with lower associated costs, according to a retrospective analysis of real-world use that was presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

When liraglutide or glargine was added to a combined metformin-plus-sulfonylurea therapy in a previous phase III trial, liraglutide demonstrated a greater reduction in hemoglobin A1c than did glargine (Diabetologia 2009;52:2046-55).

To date, however, no real-world comparative data have been published comparing use of injectable therapy with insulin glargine vs. the glucagonlike peptide–1 agonist liraglutide among patients with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Philip Levin, director of the diabetes center at Mercy Medical Center, Baltimore.

Administrative claims data were analyzed from a managed care database comprising about 50 U.S. health care plans and 107 million patients. Of those, investigators identified 967 adults who had type 2 diabetes and had initiated injectable pen therapy with either glargine (n = 557) or liraglutide (n = 410) between January and June 2010. All patients who had baseline HbA1c levels less than 7% were excluded, because it’s possible that they were started on liraglutide for weight loss rather than glucose control, Dr. Levin noted.

Because there were significant differences between the two groups at baseline – glargine initiators were older, sicker, less obese, and more likely to be male, and had higher HbA1c levels, among other differences – the 336 eligible patients were propensity matched to make the two groups more comparable. After that was done, the 168 glargine and 168 liraglutide patients did not differ significantly in sex (46% of glargine and 44% of liraglutide patients were women), age (53 years for both groups), mean Charlson comorbidity index (0.29 and 0.36, respectively), or other baseline characteristics.

The group taking glargine stayed on therapy significantly longer than did those on liraglutide (279 vs. 257 day).

Reductions in HbA1c from baseline did not differ significantly between the glargine and liraglutide groups, decreasing from 8.96% to 7.94% at 1 year with glargine, and from 8.76% to 7.81% with liraglutide (reductions of 1.02 and 0.95 percentage points, respectively). The average dose for glargine was 27.4 U/day, and for liraglutide was 1.16 mg/day.

Hypoglycemia was more common with glargine (7.7% vs. 4.7%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. Hypoglycemia requiring emergency department or inpatient treatment occurred in just 1.1% of both groups.

Health care costs were significantly lower with glargine. Study drug costs were $1,198 for glargine vs. $2,784 for liraglutide; diabetes-related drug costs were $2,958 vs. $3,988, respectively; and total diabetes-related costs were $5,653 vs. $7,976. Each of those differences was statistically significant, Dr. Levin said.

These findings will be further explored by the planned INITIATOR study, a large-scale hybrid prospective/retrospective real-world study, he noted.

The study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Levin disclosed that he is on the advisory panel for that company, as well as for Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide. He also consults for, receives research support from, or is on the speakers bureau for a long list of other manufacturers of diabetes-related products.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Reductions in HbA1c from baseline did not differ significantly between the glargine and liraglutide groups (from 8.96% to 7.94% at 1 year with glargine, and from 8.76% to 7.81% with liraglutide). However, health care costs were significantly lower with glargine. Study drug costs were $1,198 for glargine vs. $2,784 for liraglutide; diabetes-related drug costs were $2,958 vs. $3,988, respectively; and total diabetes-related costs were $5,653 vs. $7,976.

Data Source: The findings come from a retrospective database analysis of real-world use of glargine and liraglutide in 336 patients with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Levin disclosed that he is on the advisory panel for that company, as well as for Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide. He also consults for, receives research support from, or is on the speakers bureau for a long list of other manufacturers of diabetes-related products.

Postpartum Glucose Won't Predict 6-Week Diabetes

PHILADELPHIA – An elevated postpartum fasting blood sugar does not predict type 2 diabetes in women who had gestational diabetes.

Out of nine women with an elevated fasting glucose after giving birth, only two went on to a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes 6 weeks later, Dr. Hilary Roeder said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

"That means that if we had used the postpartum glucose value as a diagnostic tool, seven women would have been misdiagnosed," Dr. Roeder, an ob.gyn. at Scripps Health in San Diego, said in an interview. "We still have no good way to know specifically which women with gestational diabetes will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes."

For women with gestational diabetes, an oral glucose tolerance test should be done 6 weeks after delivery, the American Diabetes Association recommends. But some new mothers don’t make it back to the doctor at that time, Dr. Roeder said.

"We still have no good way to know specifically which women with gestational diabetes will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes."

"The problem with formal screening at the 6-week postpartum appointment is that patients don’t always come back for this visit," she said. "They get busy with the new baby or have already gone back to work and they don’t follow up. Or if they do, they often are not fasting – a requirement to perform formal screening for type 2 diabetes. Our thought was that if we could diagnose them prior to discharge from the hospital, we could set up a follow-up visit with a primary care physician or an endocrinologist so they can get proper care."

She employed a retrospective cohort study to determine whether postpartum glucose on the day of delivery was associated with a later type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Although there were 545 patients with gestational diabetes in the records, only 165 (30%) had a formal diabetes screen at 6 weeks – illustrating the poor rate of follow-up in the cohort.

Of those who were tested at 6 weeks, 111 also had a postpartum fasting glucose available for review. The patients had a mean age of 32 years, with a mean body mass index of 31 kg/m2. They had a mean gestation of 25 weeks when diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

Nine of those with a postpartum test had glucose levels above 126 mg/dL. But 6 weeks later, only two of those women were found to have type 2 diabetes.

When Dr. Roeder compared the postpartum glucose levels between patients, she found no significant difference between those who developed type 2 diabetes and those who did not. In fact, had the diagnosis been made immediately post partum, six additional women who did develop diabetes would have been missed, as their blood sugar was less than 126 mg/dL after delivery.

Overall, postpartum blood glucose levels were significantly higher than 6-week levels (mean 101 mg/dL vs. 93 mg/dL). Dr. Roeder said she believes human placental lactogen and other placentally-derived hormones could be responsible for this in part. The hormones keep glucose in the maternal bloodstream, making it more available for fetal metabolism. This results in higher maternal glucose levels, which take some time after birth to decline.

"Even though the placenta has been removed, the hormones are still circulating for an indefinite time after birth," she said.

Because immediate postpartum testing does not appear helpful, Dr. Roeder said it’s critical that women with gestational diabetes attend their 6-week checkup and have a full diabetes screen.

"We really need to impress upon our patients how important this visit is to their future health."

Dr. Roeder had no financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – An elevated postpartum fasting blood sugar does not predict type 2 diabetes in women who had gestational diabetes.

Out of nine women with an elevated fasting glucose after giving birth, only two went on to a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes 6 weeks later, Dr. Hilary Roeder said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

"That means that if we had used the postpartum glucose value as a diagnostic tool, seven women would have been misdiagnosed," Dr. Roeder, an ob.gyn. at Scripps Health in San Diego, said in an interview. "We still have no good way to know specifically which women with gestational diabetes will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes."

For women with gestational diabetes, an oral glucose tolerance test should be done 6 weeks after delivery, the American Diabetes Association recommends. But some new mothers don’t make it back to the doctor at that time, Dr. Roeder said.

"We still have no good way to know specifically which women with gestational diabetes will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes."

"The problem with formal screening at the 6-week postpartum appointment is that patients don’t always come back for this visit," she said. "They get busy with the new baby or have already gone back to work and they don’t follow up. Or if they do, they often are not fasting – a requirement to perform formal screening for type 2 diabetes. Our thought was that if we could diagnose them prior to discharge from the hospital, we could set up a follow-up visit with a primary care physician or an endocrinologist so they can get proper care."

She employed a retrospective cohort study to determine whether postpartum glucose on the day of delivery was associated with a later type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Although there were 545 patients with gestational diabetes in the records, only 165 (30%) had a formal diabetes screen at 6 weeks – illustrating the poor rate of follow-up in the cohort.

Of those who were tested at 6 weeks, 111 also had a postpartum fasting glucose available for review. The patients had a mean age of 32 years, with a mean body mass index of 31 kg/m2. They had a mean gestation of 25 weeks when diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

Nine of those with a postpartum test had glucose levels above 126 mg/dL. But 6 weeks later, only two of those women were found to have type 2 diabetes.

When Dr. Roeder compared the postpartum glucose levels between patients, she found no significant difference between those who developed type 2 diabetes and those who did not. In fact, had the diagnosis been made immediately post partum, six additional women who did develop diabetes would have been missed, as their blood sugar was less than 126 mg/dL after delivery.

Overall, postpartum blood glucose levels were significantly higher than 6-week levels (mean 101 mg/dL vs. 93 mg/dL). Dr. Roeder said she believes human placental lactogen and other placentally-derived hormones could be responsible for this in part. The hormones keep glucose in the maternal bloodstream, making it more available for fetal metabolism. This results in higher maternal glucose levels, which take some time after birth to decline.

"Even though the placenta has been removed, the hormones are still circulating for an indefinite time after birth," she said.

Because immediate postpartum testing does not appear helpful, Dr. Roeder said it’s critical that women with gestational diabetes attend their 6-week checkup and have a full diabetes screen.

"We really need to impress upon our patients how important this visit is to their future health."

Dr. Roeder had no financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – An elevated postpartum fasting blood sugar does not predict type 2 diabetes in women who had gestational diabetes.

Out of nine women with an elevated fasting glucose after giving birth, only two went on to a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes 6 weeks later, Dr. Hilary Roeder said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

"That means that if we had used the postpartum glucose value as a diagnostic tool, seven women would have been misdiagnosed," Dr. Roeder, an ob.gyn. at Scripps Health in San Diego, said in an interview. "We still have no good way to know specifically which women with gestational diabetes will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes."

For women with gestational diabetes, an oral glucose tolerance test should be done 6 weeks after delivery, the American Diabetes Association recommends. But some new mothers don’t make it back to the doctor at that time, Dr. Roeder said.

"We still have no good way to know specifically which women with gestational diabetes will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes."

"The problem with formal screening at the 6-week postpartum appointment is that patients don’t always come back for this visit," she said. "They get busy with the new baby or have already gone back to work and they don’t follow up. Or if they do, they often are not fasting – a requirement to perform formal screening for type 2 diabetes. Our thought was that if we could diagnose them prior to discharge from the hospital, we could set up a follow-up visit with a primary care physician or an endocrinologist so they can get proper care."

She employed a retrospective cohort study to determine whether postpartum glucose on the day of delivery was associated with a later type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Although there were 545 patients with gestational diabetes in the records, only 165 (30%) had a formal diabetes screen at 6 weeks – illustrating the poor rate of follow-up in the cohort.

Of those who were tested at 6 weeks, 111 also had a postpartum fasting glucose available for review. The patients had a mean age of 32 years, with a mean body mass index of 31 kg/m2. They had a mean gestation of 25 weeks when diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

Nine of those with a postpartum test had glucose levels above 126 mg/dL. But 6 weeks later, only two of those women were found to have type 2 diabetes.

When Dr. Roeder compared the postpartum glucose levels between patients, she found no significant difference between those who developed type 2 diabetes and those who did not. In fact, had the diagnosis been made immediately post partum, six additional women who did develop diabetes would have been missed, as their blood sugar was less than 126 mg/dL after delivery.

Overall, postpartum blood glucose levels were significantly higher than 6-week levels (mean 101 mg/dL vs. 93 mg/dL). Dr. Roeder said she believes human placental lactogen and other placentally-derived hormones could be responsible for this in part. The hormones keep glucose in the maternal bloodstream, making it more available for fetal metabolism. This results in higher maternal glucose levels, which take some time after birth to decline.

"Even though the placenta has been removed, the hormones are still circulating for an indefinite time after birth," she said.

Because immediate postpartum testing does not appear helpful, Dr. Roeder said it’s critical that women with gestational diabetes attend their 6-week checkup and have a full diabetes screen.

"We really need to impress upon our patients how important this visit is to their future health."

Dr. Roeder had no financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Of nine women with gestational diabetes and elevated postpartum blood glucose, only two were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at 6 weeks. Six women with lower postpartum glucose ended up with a diabetes diagnosis at the 6-week checkup.

Data Source: This was a retrospective study of 545 women with gestational diabetes.

Disclosures: Dr. Roeder had no disclosures.

Experimental Peptide Preserves Beta-Cells in Type 1 Diabetes

PHILADELPHIA – An investigational peptide successfully preserved beta-cell function at 2 years in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial that enrolled more than 450 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes.

DiaPep277, a synthetic 24 amino acid peptide derived from human heat shock protein 60, modulates the immune response that leads to autoimmune diabetes by diminishing or blocking the immunological destruction of beta cells. In May 2012, the Food and Drug Administration granted DiaPep277 an Orphan Drug designation for the treatment of type 1 diabetes patients with residual beta cell function, according to statement from Andromeda Biotech, the drug’s developer.

Potential target populations include newly diagnosed adult patients, type 1 diabetic children, people with a high risk of developing type 1 diabetes, and type 1 diabetes patients with slow-progressing disease. Potential benefits include prevention of disease deterioration, improved glycemic control, reduction of daily insulin dose requirements, and delay or reduction of diabetes complications, the company statement said.

Data from the first of two phase III studies – conducted at 40 centers in Europe, Israel, and South Africa – were presented by Dr. Paolo Pozzilli, professor of endocrinology at Università Campus Bio-Medico, Rome. Inclusion criteria for the study were age 16-45 years, no more than 3 months since type 1 diabetes diagnosis, fasting C-peptide greater than 0.2 nmol/L, and positive islet autoantibodies. Subcutaneous injections of DiaPep277 or placebo were given every 3 months. Of the 457 initially randomized, 175 received all nine DiaPep277 injections and 174 received the total of nine placebo injections over the entire 24 month study period.

The primary efficacy end point – change from baseline to end of study in stimulated C-peptide area under curve secretion measured by the glucagon stimulated test – was met. There was significant preservation of C-peptide levels compared to placebo, with a relative change of 23% (P = .037) for all the randomized patients, and an even more significant preservation for the patients who completed 2 years of therapy in full compliance with the study protocol, with a 29% relative change (P = .011).

A secondary end point, the proportion of patients maintaining/achieving a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or less, also was met, with 56% of DiaPep277 patients vs. 44% of those on placebo achieving that goal in the per-protocol evaluation (P = .035). Patients on lower doses of insulin were more likely to achieve an HbA1c of 7% or less, Dr. Pozzilli noted.

Another secondary end point, change from baseline in C-peptide using a mixed-meal tolerance test, was not met, he added.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in those who reported one or more adverse event of any kind (77% for DiaPep277 vs. 71% for placebo), serious adverse events (12% vs. 6%, respectively) or adverse events believed to be drug related (1.3% vs. 0.4%). Hypoglycemia was significantly less frequent in the DiaPep277 group (P = .04).

"We can conclude there is a significant treatment effect without adverse events ... Hopefully we can have something to offer patients with type 1 diabetes at diagnosis," he concluded.

A second large phase III clinical trial of DiaPep277 in newly diagnosed type 1 patients is underway. Results are expected in 2015, he said.

Dr. Pozzilli has consulted for Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Andromeda-Biotech, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, and Medtronic. Andromeda-Biotech licensed the peptide from Yeda Research & Development Company, the commercial arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel.

PHILADELPHIA – An investigational peptide successfully preserved beta-cell function at 2 years in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial that enrolled more than 450 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes.

DiaPep277, a synthetic 24 amino acid peptide derived from human heat shock protein 60, modulates the immune response that leads to autoimmune diabetes by diminishing or blocking the immunological destruction of beta cells. In May 2012, the Food and Drug Administration granted DiaPep277 an Orphan Drug designation for the treatment of type 1 diabetes patients with residual beta cell function, according to statement from Andromeda Biotech, the drug’s developer.

Potential target populations include newly diagnosed adult patients, type 1 diabetic children, people with a high risk of developing type 1 diabetes, and type 1 diabetes patients with slow-progressing disease. Potential benefits include prevention of disease deterioration, improved glycemic control, reduction of daily insulin dose requirements, and delay or reduction of diabetes complications, the company statement said.

Data from the first of two phase III studies – conducted at 40 centers in Europe, Israel, and South Africa – were presented by Dr. Paolo Pozzilli, professor of endocrinology at Università Campus Bio-Medico, Rome. Inclusion criteria for the study were age 16-45 years, no more than 3 months since type 1 diabetes diagnosis, fasting C-peptide greater than 0.2 nmol/L, and positive islet autoantibodies. Subcutaneous injections of DiaPep277 or placebo were given every 3 months. Of the 457 initially randomized, 175 received all nine DiaPep277 injections and 174 received the total of nine placebo injections over the entire 24 month study period.

The primary efficacy end point – change from baseline to end of study in stimulated C-peptide area under curve secretion measured by the glucagon stimulated test – was met. There was significant preservation of C-peptide levels compared to placebo, with a relative change of 23% (P = .037) for all the randomized patients, and an even more significant preservation for the patients who completed 2 years of therapy in full compliance with the study protocol, with a 29% relative change (P = .011).

A secondary end point, the proportion of patients maintaining/achieving a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or less, also was met, with 56% of DiaPep277 patients vs. 44% of those on placebo achieving that goal in the per-protocol evaluation (P = .035). Patients on lower doses of insulin were more likely to achieve an HbA1c of 7% or less, Dr. Pozzilli noted.

Another secondary end point, change from baseline in C-peptide using a mixed-meal tolerance test, was not met, he added.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in those who reported one or more adverse event of any kind (77% for DiaPep277 vs. 71% for placebo), serious adverse events (12% vs. 6%, respectively) or adverse events believed to be drug related (1.3% vs. 0.4%). Hypoglycemia was significantly less frequent in the DiaPep277 group (P = .04).

"We can conclude there is a significant treatment effect without adverse events ... Hopefully we can have something to offer patients with type 1 diabetes at diagnosis," he concluded.

A second large phase III clinical trial of DiaPep277 in newly diagnosed type 1 patients is underway. Results are expected in 2015, he said.

Dr. Pozzilli has consulted for Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Andromeda-Biotech, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, and Medtronic. Andromeda-Biotech licensed the peptide from Yeda Research & Development Company, the commercial arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel.

PHILADELPHIA – An investigational peptide successfully preserved beta-cell function at 2 years in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial that enrolled more than 450 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes.

DiaPep277, a synthetic 24 amino acid peptide derived from human heat shock protein 60, modulates the immune response that leads to autoimmune diabetes by diminishing or blocking the immunological destruction of beta cells. In May 2012, the Food and Drug Administration granted DiaPep277 an Orphan Drug designation for the treatment of type 1 diabetes patients with residual beta cell function, according to statement from Andromeda Biotech, the drug’s developer.

Potential target populations include newly diagnosed adult patients, type 1 diabetic children, people with a high risk of developing type 1 diabetes, and type 1 diabetes patients with slow-progressing disease. Potential benefits include prevention of disease deterioration, improved glycemic control, reduction of daily insulin dose requirements, and delay or reduction of diabetes complications, the company statement said.

Data from the first of two phase III studies – conducted at 40 centers in Europe, Israel, and South Africa – were presented by Dr. Paolo Pozzilli, professor of endocrinology at Università Campus Bio-Medico, Rome. Inclusion criteria for the study were age 16-45 years, no more than 3 months since type 1 diabetes diagnosis, fasting C-peptide greater than 0.2 nmol/L, and positive islet autoantibodies. Subcutaneous injections of DiaPep277 or placebo were given every 3 months. Of the 457 initially randomized, 175 received all nine DiaPep277 injections and 174 received the total of nine placebo injections over the entire 24 month study period.

The primary efficacy end point – change from baseline to end of study in stimulated C-peptide area under curve secretion measured by the glucagon stimulated test – was met. There was significant preservation of C-peptide levels compared to placebo, with a relative change of 23% (P = .037) for all the randomized patients, and an even more significant preservation for the patients who completed 2 years of therapy in full compliance with the study protocol, with a 29% relative change (P = .011).

A secondary end point, the proportion of patients maintaining/achieving a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or less, also was met, with 56% of DiaPep277 patients vs. 44% of those on placebo achieving that goal in the per-protocol evaluation (P = .035). Patients on lower doses of insulin were more likely to achieve an HbA1c of 7% or less, Dr. Pozzilli noted.

Another secondary end point, change from baseline in C-peptide using a mixed-meal tolerance test, was not met, he added.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in those who reported one or more adverse event of any kind (77% for DiaPep277 vs. 71% for placebo), serious adverse events (12% vs. 6%, respectively) or adverse events believed to be drug related (1.3% vs. 0.4%). Hypoglycemia was significantly less frequent in the DiaPep277 group (P = .04).

"We can conclude there is a significant treatment effect without adverse events ... Hopefully we can have something to offer patients with type 1 diabetes at diagnosis," he concluded.

A second large phase III clinical trial of DiaPep277 in newly diagnosed type 1 patients is underway. Results are expected in 2015, he said.

Dr. Pozzilli has consulted for Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Andromeda-Biotech, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, and Medtronic. Andromeda-Biotech licensed the peptide from Yeda Research & Development Company, the commercial arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: There was significant preservation of C-peptide levels, compared with placebo, with a relative change of 23% (P = .037) for all the randomized patients and an even more significant preservation for the patients who completed 2 years of therapy in full compliance with the study protocol, with a 29% relative change (P = .011).

Data Source: The data come from a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase III trial that enrolled 457 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Andromeda Biotech. Dr. Pozzilli has consulted for that company, as well as for Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, and Medtronic.

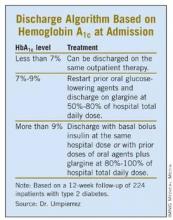

Admission HbA1c Aids Discharge Planning

PHILADELPHIA – An algorithm based on hemoglobin A1c levels at admission was safe and effective in guiding diabetes therapy after discharge, based on a prospective, randomized pilot study of 224 inpatients with type 2 diabetes.

Average HbA1c dropped from 8.4% on admission to 7.9% at 4 weeks and to 7.3% at 12 weeks after discharge, said Dr. Guillermo E. Umpierrez, professor of medicine at Emory University, and chief of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta.

"If we can do this at Grady Hospital, a county hospital in downtown Atlanta, I think most of you can do it in your facilities. We see these patients within 2 weeks of discharge. I think frequent followup and education are key to [the success of] this type of program," Dr. Umpierrez said.

The patients were placed into one of three post-discharge treatment groups based on their HbA1c levels at admission. Patients with admission HbA1c values of less than 7% resumed their previous outpatient treatments at discharge. Those with HbA1c values of 7%-9% resumed their outpatient oral agents at discharge along with once-daily glargine at 50%-80% of the hospital dose. Patients admitted with a HbA1c level above 9% were discharged on their oral agents plus glargine at 80%-100% of the hospital dose or with the same basal and bolus insulin doses as they’d been given in the hospital.

The treatment goal after discharge was a blood glucose range of 70-130 mg/dL (fasting and premeal) and a HbA1c value below 7%, Dr. Umpierrez said.

For the group discharged on oral agents alone, average HbA1c fell from 6.9% at admission to 6.6% at 12 week follow-up. For those discharged on oral agents plus glargine, average HbA1c fell from 9.2% at admission to 7.5% at 12 weeks. For those discharged on glargine plus glulisine, average HbA1c fell from 11.1% to 8.0% at 12 weeks, Dr. Umpierrez reported.

Hypoglycemia with blood glucose levels below 70 mg/dL occurred post-discharge in 22% of those discharged on oral agents, 30% on oral agents plus glargine, and 44% on glargine plus glulisine. However, hypoglycemia with blood glucose values less than 40 mg/dl occurred in 3% of all patients and in 6% of the group on glargine plus glulisine.

The 224 study patients were a subset of the 375 participants in Sanofi-Aventis’ multicenter "Basal Plus" trial. That study of medical and surgical inpatients with previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes compared the efficacy and safety of a daily dose of glargine plus corrective doses of glulisine ("basal plus") to basal-bolus insulin and sliding scale regular insulin regimens.

At admission, the mean blood glucose level was 204 mg/dL (range 140-400 mg/dL), and the mean admission HbA1c was 8.4%. A total of 150 patients were randomized to the basal-bolus regimen, 148 to "basal plus" regimen, and 77 to the sliding scale insulin regimen.

During hospitalization, patients in the basal-bolus group were started at 0.5 U/kg, given half as glargine once daily and half as glulisine before meals. The "basal plus" group received 0.25 U/kg of glargine once daily plus correction doses of glulisine before meals for blood glucose values above 140 mg/dL. Sliding scale insulin was given four times a day for blood glucose values above 140 mg/dL.

Results from the in-hospital patients in the basal plus trial were reported by Dr. Umpierrez and his fellow researchers in a poster. The basal plus and basal bolus regimens resulted in similar glycemic control, with worse outcomes for those on sliding scale insulin. Mean daily blood glucose values after day 1 were 172 mg/dL for sliding scale insulin, 156 mg/dL for basal bolus, and 163 mg/dL for basal plus. Treatment failures, defined as more than two consecutive blood glucose values or a mean daily glucose value greater than 240 mg/dL, occurred in 19% on sliding scale insulin and in 2% on the basal plus regimen (P less than .001). Glucose values of less than 70 mg/dL occurred in 16% of inpatients and in 1.7% of blood glucose readings overall. Glucose levels of less than 40 mg/dL occurred in 1% of the basal bolus and the basal plus groups, and in none of the inpatients on sliding scale insulin.

There were no differences in length of stay or complications including wound infections, pneumonia, respiratory or renal failure and bacteremia between groups, the investigators reported.

This study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Umpierrez disclosed that he has also received research support from Merck.

PHILADELPHIA – An algorithm based on hemoglobin A1c levels at admission was safe and effective in guiding diabetes therapy after discharge, based on a prospective, randomized pilot study of 224 inpatients with type 2 diabetes.

Average HbA1c dropped from 8.4% on admission to 7.9% at 4 weeks and to 7.3% at 12 weeks after discharge, said Dr. Guillermo E. Umpierrez, professor of medicine at Emory University, and chief of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta.

"If we can do this at Grady Hospital, a county hospital in downtown Atlanta, I think most of you can do it in your facilities. We see these patients within 2 weeks of discharge. I think frequent followup and education are key to [the success of] this type of program," Dr. Umpierrez said.

The patients were placed into one of three post-discharge treatment groups based on their HbA1c levels at admission. Patients with admission HbA1c values of less than 7% resumed their previous outpatient treatments at discharge. Those with HbA1c values of 7%-9% resumed their outpatient oral agents at discharge along with once-daily glargine at 50%-80% of the hospital dose. Patients admitted with a HbA1c level above 9% were discharged on their oral agents plus glargine at 80%-100% of the hospital dose or with the same basal and bolus insulin doses as they’d been given in the hospital.

The treatment goal after discharge was a blood glucose range of 70-130 mg/dL (fasting and premeal) and a HbA1c value below 7%, Dr. Umpierrez said.

For the group discharged on oral agents alone, average HbA1c fell from 6.9% at admission to 6.6% at 12 week follow-up. For those discharged on oral agents plus glargine, average HbA1c fell from 9.2% at admission to 7.5% at 12 weeks. For those discharged on glargine plus glulisine, average HbA1c fell from 11.1% to 8.0% at 12 weeks, Dr. Umpierrez reported.

Hypoglycemia with blood glucose levels below 70 mg/dL occurred post-discharge in 22% of those discharged on oral agents, 30% on oral agents plus glargine, and 44% on glargine plus glulisine. However, hypoglycemia with blood glucose values less than 40 mg/dl occurred in 3% of all patients and in 6% of the group on glargine plus glulisine.

The 224 study patients were a subset of the 375 participants in Sanofi-Aventis’ multicenter "Basal Plus" trial. That study of medical and surgical inpatients with previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes compared the efficacy and safety of a daily dose of glargine plus corrective doses of glulisine ("basal plus") to basal-bolus insulin and sliding scale regular insulin regimens.

At admission, the mean blood glucose level was 204 mg/dL (range 140-400 mg/dL), and the mean admission HbA1c was 8.4%. A total of 150 patients were randomized to the basal-bolus regimen, 148 to "basal plus" regimen, and 77 to the sliding scale insulin regimen.

During hospitalization, patients in the basal-bolus group were started at 0.5 U/kg, given half as glargine once daily and half as glulisine before meals. The "basal plus" group received 0.25 U/kg of glargine once daily plus correction doses of glulisine before meals for blood glucose values above 140 mg/dL. Sliding scale insulin was given four times a day for blood glucose values above 140 mg/dL.

Results from the in-hospital patients in the basal plus trial were reported by Dr. Umpierrez and his fellow researchers in a poster. The basal plus and basal bolus regimens resulted in similar glycemic control, with worse outcomes for those on sliding scale insulin. Mean daily blood glucose values after day 1 were 172 mg/dL for sliding scale insulin, 156 mg/dL for basal bolus, and 163 mg/dL for basal plus. Treatment failures, defined as more than two consecutive blood glucose values or a mean daily glucose value greater than 240 mg/dL, occurred in 19% on sliding scale insulin and in 2% on the basal plus regimen (P less than .001). Glucose values of less than 70 mg/dL occurred in 16% of inpatients and in 1.7% of blood glucose readings overall. Glucose levels of less than 40 mg/dL occurred in 1% of the basal bolus and the basal plus groups, and in none of the inpatients on sliding scale insulin.

There were no differences in length of stay or complications including wound infections, pneumonia, respiratory or renal failure and bacteremia between groups, the investigators reported.

This study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Umpierrez disclosed that he has also received research support from Merck.

PHILADELPHIA – An algorithm based on hemoglobin A1c levels at admission was safe and effective in guiding diabetes therapy after discharge, based on a prospective, randomized pilot study of 224 inpatients with type 2 diabetes.

Average HbA1c dropped from 8.4% on admission to 7.9% at 4 weeks and to 7.3% at 12 weeks after discharge, said Dr. Guillermo E. Umpierrez, professor of medicine at Emory University, and chief of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta.

"If we can do this at Grady Hospital, a county hospital in downtown Atlanta, I think most of you can do it in your facilities. We see these patients within 2 weeks of discharge. I think frequent followup and education are key to [the success of] this type of program," Dr. Umpierrez said.

The patients were placed into one of three post-discharge treatment groups based on their HbA1c levels at admission. Patients with admission HbA1c values of less than 7% resumed their previous outpatient treatments at discharge. Those with HbA1c values of 7%-9% resumed their outpatient oral agents at discharge along with once-daily glargine at 50%-80% of the hospital dose. Patients admitted with a HbA1c level above 9% were discharged on their oral agents plus glargine at 80%-100% of the hospital dose or with the same basal and bolus insulin doses as they’d been given in the hospital.

The treatment goal after discharge was a blood glucose range of 70-130 mg/dL (fasting and premeal) and a HbA1c value below 7%, Dr. Umpierrez said.

For the group discharged on oral agents alone, average HbA1c fell from 6.9% at admission to 6.6% at 12 week follow-up. For those discharged on oral agents plus glargine, average HbA1c fell from 9.2% at admission to 7.5% at 12 weeks. For those discharged on glargine plus glulisine, average HbA1c fell from 11.1% to 8.0% at 12 weeks, Dr. Umpierrez reported.

Hypoglycemia with blood glucose levels below 70 mg/dL occurred post-discharge in 22% of those discharged on oral agents, 30% on oral agents plus glargine, and 44% on glargine plus glulisine. However, hypoglycemia with blood glucose values less than 40 mg/dl occurred in 3% of all patients and in 6% of the group on glargine plus glulisine.

The 224 study patients were a subset of the 375 participants in Sanofi-Aventis’ multicenter "Basal Plus" trial. That study of medical and surgical inpatients with previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes compared the efficacy and safety of a daily dose of glargine plus corrective doses of glulisine ("basal plus") to basal-bolus insulin and sliding scale regular insulin regimens.

At admission, the mean blood glucose level was 204 mg/dL (range 140-400 mg/dL), and the mean admission HbA1c was 8.4%. A total of 150 patients were randomized to the basal-bolus regimen, 148 to "basal plus" regimen, and 77 to the sliding scale insulin regimen.

During hospitalization, patients in the basal-bolus group were started at 0.5 U/kg, given half as glargine once daily and half as glulisine before meals. The "basal plus" group received 0.25 U/kg of glargine once daily plus correction doses of glulisine before meals for blood glucose values above 140 mg/dL. Sliding scale insulin was given four times a day for blood glucose values above 140 mg/dL.

Results from the in-hospital patients in the basal plus trial were reported by Dr. Umpierrez and his fellow researchers in a poster. The basal plus and basal bolus regimens resulted in similar glycemic control, with worse outcomes for those on sliding scale insulin. Mean daily blood glucose values after day 1 were 172 mg/dL for sliding scale insulin, 156 mg/dL for basal bolus, and 163 mg/dL for basal plus. Treatment failures, defined as more than two consecutive blood glucose values or a mean daily glucose value greater than 240 mg/dL, occurred in 19% on sliding scale insulin and in 2% on the basal plus regimen (P less than .001). Glucose values of less than 70 mg/dL occurred in 16% of inpatients and in 1.7% of blood glucose readings overall. Glucose levels of less than 40 mg/dL occurred in 1% of the basal bolus and the basal plus groups, and in none of the inpatients on sliding scale insulin.

There were no differences in length of stay or complications including wound infections, pneumonia, respiratory or renal failure and bacteremia between groups, the investigators reported.

This study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Umpierrez disclosed that he has also received research support from Merck.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: In the postdischarge cohort, hemoglobin A1c dropped from 8.7% on admission to 7.3% at 12 weeks after discharge.

Data Source: The 224 post-discharge study patients were a subset of 375 inpatients in a trial that compared the efficacy and safety of a daily dose of glargine plus corrective doses of glulisine to basal-bolus insulin and sliding scale regular insulin regimens.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Umpierrez disclosed that he has also received research support from Merck.

Genetic Screening Targets Maturity-Onset Diabetes of Youth

PHILADELPHIA – In people aged 20-40 years who have been diagnosed with diabetes, routine genetic screening for maturity-onset diabetes of youth could result in more targeted treatment. But the costs of genetic testing need to come down before routine screening becomes cost effective.

Using a simulation model of type 2 diabetes complications that accounted for the natural history of disease by genetic subtypes, investigators found that genetic screening added 0.01 quality-adjusted life-years (19.22 vs. 19.21 with no screening) at an increased total cost of $1,727 ($41,033 vs. $39,306). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (or cost per quality-adjusted life-years) was $143,409.

Genetic testing becomes more cost effective as the cost of the test decreases. If the prevalence of maturity-onset diabetes of youth (MODY) in the screened population is 5% or greater, and the cost of the test drops to less than $1,000, then the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio would go to $50,000, which is considered to be the conventional cost-effectiveness threshold. If the test cost falls to $200, then the screening policy would be cost saving, presuming that the MODY prevalence in the screened population was 20% or higher, said Dr. Rochelle N. Naylor, a pediatric endocrinology fellow at the University of Chicago’s National Center for Monogenic Diabetes.

MODY is caused by mutations in 11 different genes; just 3 of them account for 80% of cases of MODY. Screening can aid treatment decisions because mutations in either HNF1A or HNF4A lead to a progressive insulin secretory defect for which sulfonylureas are the established first-line therapy. Mutations in GCK, on the other hand, result in permanent but mild blood glucose elevations and don’t require treatment.