User login

A 32-year-old man presented to the ED with acute onset of left testicular swelling and pain. He described the pain as severe, radiating to his lower back and lower abdomen. Regarding his medical history, the patient stated he had experienced similar episodes of significant testicular swelling in the past, for which he was treated with antibiotics.

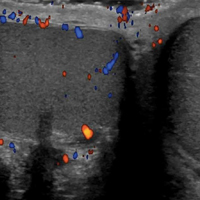

Physical examination revealed mild enlargement of the left testis with tenderness to palpation. The right testis was normal in appearance and nontender. An ultrasound study of the testicles was ordered; representative images are shown (Figures 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

The transverse image of both testes demonstrated an enlarged left testicle compared to the right testicle (Figure 2a). On color-flow Doppler ultrasound, spots of color within the testicle were noted within the right testicle only. The lack of blood flow was confirmed on the sagittal image of the left testicle, which also revealed a small hydrocele (white arrows, Figure 2b). A sagittal color Doppler image of the normal right testicle showed color flow (white arrows, Figure 2c) and normal vascular waveforms (red arrow, Figure 2c) within the testis, but no hydrocele, confirming the diagnosis of left testicular torsion. The Doppler ultrasound of the right testicle (white arrows, Figure 2c) further confirmed a normal right testicle but no evidence of flow in the left testicle. These findings were further consistent with the presence of left testicular torsion.

Answer

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency that results from a twisting of the spermatic cord, cutting off arterial flow to, and venous drainage from, the affected testis. There are two types of testicular torsion depending on which side of the tunica vaginalis (the serous membrane pouch covering the testes) the torsion occurs: extra vaginal, seen mainly in newborns; and intravaginal, which can occur at any age, but is more common in adolescents.

“Bell clapper deformity” is a predisposing congenital condition resulting from intravaginal torsion of the testis in which the tunica vaginalis joins high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testis free to rotate.1 Testicular torsion most commonly occurs in young males, with an estimated incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 patients between ages 1 and 25 years.2

Clinical Presentation

Patients with testicular torsion typically experience a sudden onset of severe unilateral pain often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which can occur spontaneously or after vigorous physical activity or trauma. Associated complaints may include urinary symptoms and/or fever.3 The affected testis may lie transversely in the scrotum and be retracted, although physical examination is often nonspecific and unreliable. Since an absence of the cremasteric reflex is neither sensitive nor specific in determining the need for surgical intervention, further diagnostic testing is required.4

Doppler Ultrasound

Ultrasound utilizing color and spectral Doppler techniques is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for testicular torsion, and has a reported sensitivity of 82% to 89%, and a specificity of 98% to 100%.5,6 Ultrasound findings include enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the affected testicle due to edema. Scrotal wall thickening and a small hydrocele also may be seen. Doppler imaging also typically demonstrates absence of flow, though hyperemia and increased flow may be present early in the disease process.

It is important to note that torsion may be intermittent; therefore, imaging studies can appear normal during periods of intermittent perfusion. If there is incomplete torsion and some arterial flow persists in the affected testis, comparison of the two testes using transverse views is very useful in making the diagnosis.7

With respect to the differential diagnoses, ultrasound imaging studies are also useful in diagnosing other conditions associated with testicular pain, including torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, varicocele, and tumors.

Treatment

Rapid diagnosis of testicular torsion is important, as delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible damage and loss of the testicle. Infertility can result even with a normal contralateral testis.8 When surgical intervention is performed within 6 hours from onset of torsion, salvage of the testicle has been reported to be 90% to 100%, but only 50% and 10% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively.3 The patient in this case was taken immediately for emergent surgical detorsion, and the left testicle was salvaged.

1. Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 1994;44 (1):114-116.

2. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1167.

3. Sharp VJ, Kieran K, Arlen AM. Testicular torsion: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(12):835-840.

4. Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: It is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:80Y86. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f5ed9.

5. Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):604-607.

6. Burks DD, Markey BJ, Burkhard TK, Balsara ZN, Haluszka MM, Canning DA. Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1990;175(3):815-821. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188301.

7. Aso C, Enríquez G, Fité M, et al. Gray-scale and color doppler sonography of scrotal disorders in children: an update. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1197-1214. doi:10.1148/rg.255045109.

8. Hadziselimovic F, Geneto R, Emmons LR. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J Urol. 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1158-1160.

A 32-year-old man presented to the ED with acute onset of left testicular swelling and pain. He described the pain as severe, radiating to his lower back and lower abdomen. Regarding his medical history, the patient stated he had experienced similar episodes of significant testicular swelling in the past, for which he was treated with antibiotics.

Physical examination revealed mild enlargement of the left testis with tenderness to palpation. The right testis was normal in appearance and nontender. An ultrasound study of the testicles was ordered; representative images are shown (Figures 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

The transverse image of both testes demonstrated an enlarged left testicle compared to the right testicle (Figure 2a). On color-flow Doppler ultrasound, spots of color within the testicle were noted within the right testicle only. The lack of blood flow was confirmed on the sagittal image of the left testicle, which also revealed a small hydrocele (white arrows, Figure 2b). A sagittal color Doppler image of the normal right testicle showed color flow (white arrows, Figure 2c) and normal vascular waveforms (red arrow, Figure 2c) within the testis, but no hydrocele, confirming the diagnosis of left testicular torsion. The Doppler ultrasound of the right testicle (white arrows, Figure 2c) further confirmed a normal right testicle but no evidence of flow in the left testicle. These findings were further consistent with the presence of left testicular torsion.

Answer

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency that results from a twisting of the spermatic cord, cutting off arterial flow to, and venous drainage from, the affected testis. There are two types of testicular torsion depending on which side of the tunica vaginalis (the serous membrane pouch covering the testes) the torsion occurs: extra vaginal, seen mainly in newborns; and intravaginal, which can occur at any age, but is more common in adolescents.

“Bell clapper deformity” is a predisposing congenital condition resulting from intravaginal torsion of the testis in which the tunica vaginalis joins high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testis free to rotate.1 Testicular torsion most commonly occurs in young males, with an estimated incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 patients between ages 1 and 25 years.2

Clinical Presentation

Patients with testicular torsion typically experience a sudden onset of severe unilateral pain often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which can occur spontaneously or after vigorous physical activity or trauma. Associated complaints may include urinary symptoms and/or fever.3 The affected testis may lie transversely in the scrotum and be retracted, although physical examination is often nonspecific and unreliable. Since an absence of the cremasteric reflex is neither sensitive nor specific in determining the need for surgical intervention, further diagnostic testing is required.4

Doppler Ultrasound

Ultrasound utilizing color and spectral Doppler techniques is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for testicular torsion, and has a reported sensitivity of 82% to 89%, and a specificity of 98% to 100%.5,6 Ultrasound findings include enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the affected testicle due to edema. Scrotal wall thickening and a small hydrocele also may be seen. Doppler imaging also typically demonstrates absence of flow, though hyperemia and increased flow may be present early in the disease process.

It is important to note that torsion may be intermittent; therefore, imaging studies can appear normal during periods of intermittent perfusion. If there is incomplete torsion and some arterial flow persists in the affected testis, comparison of the two testes using transverse views is very useful in making the diagnosis.7

With respect to the differential diagnoses, ultrasound imaging studies are also useful in diagnosing other conditions associated with testicular pain, including torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, varicocele, and tumors.

Treatment

Rapid diagnosis of testicular torsion is important, as delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible damage and loss of the testicle. Infertility can result even with a normal contralateral testis.8 When surgical intervention is performed within 6 hours from onset of torsion, salvage of the testicle has been reported to be 90% to 100%, but only 50% and 10% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively.3 The patient in this case was taken immediately for emergent surgical detorsion, and the left testicle was salvaged.

A 32-year-old man presented to the ED with acute onset of left testicular swelling and pain. He described the pain as severe, radiating to his lower back and lower abdomen. Regarding his medical history, the patient stated he had experienced similar episodes of significant testicular swelling in the past, for which he was treated with antibiotics.

Physical examination revealed mild enlargement of the left testis with tenderness to palpation. The right testis was normal in appearance and nontender. An ultrasound study of the testicles was ordered; representative images are shown (Figures 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

The transverse image of both testes demonstrated an enlarged left testicle compared to the right testicle (Figure 2a). On color-flow Doppler ultrasound, spots of color within the testicle were noted within the right testicle only. The lack of blood flow was confirmed on the sagittal image of the left testicle, which also revealed a small hydrocele (white arrows, Figure 2b). A sagittal color Doppler image of the normal right testicle showed color flow (white arrows, Figure 2c) and normal vascular waveforms (red arrow, Figure 2c) within the testis, but no hydrocele, confirming the diagnosis of left testicular torsion. The Doppler ultrasound of the right testicle (white arrows, Figure 2c) further confirmed a normal right testicle but no evidence of flow in the left testicle. These findings were further consistent with the presence of left testicular torsion.

Answer

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency that results from a twisting of the spermatic cord, cutting off arterial flow to, and venous drainage from, the affected testis. There are two types of testicular torsion depending on which side of the tunica vaginalis (the serous membrane pouch covering the testes) the torsion occurs: extra vaginal, seen mainly in newborns; and intravaginal, which can occur at any age, but is more common in adolescents.

“Bell clapper deformity” is a predisposing congenital condition resulting from intravaginal torsion of the testis in which the tunica vaginalis joins high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testis free to rotate.1 Testicular torsion most commonly occurs in young males, with an estimated incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 patients between ages 1 and 25 years.2

Clinical Presentation

Patients with testicular torsion typically experience a sudden onset of severe unilateral pain often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which can occur spontaneously or after vigorous physical activity or trauma. Associated complaints may include urinary symptoms and/or fever.3 The affected testis may lie transversely in the scrotum and be retracted, although physical examination is often nonspecific and unreliable. Since an absence of the cremasteric reflex is neither sensitive nor specific in determining the need for surgical intervention, further diagnostic testing is required.4

Doppler Ultrasound

Ultrasound utilizing color and spectral Doppler techniques is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for testicular torsion, and has a reported sensitivity of 82% to 89%, and a specificity of 98% to 100%.5,6 Ultrasound findings include enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the affected testicle due to edema. Scrotal wall thickening and a small hydrocele also may be seen. Doppler imaging also typically demonstrates absence of flow, though hyperemia and increased flow may be present early in the disease process.

It is important to note that torsion may be intermittent; therefore, imaging studies can appear normal during periods of intermittent perfusion. If there is incomplete torsion and some arterial flow persists in the affected testis, comparison of the two testes using transverse views is very useful in making the diagnosis.7

With respect to the differential diagnoses, ultrasound imaging studies are also useful in diagnosing other conditions associated with testicular pain, including torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, varicocele, and tumors.

Treatment

Rapid diagnosis of testicular torsion is important, as delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible damage and loss of the testicle. Infertility can result even with a normal contralateral testis.8 When surgical intervention is performed within 6 hours from onset of torsion, salvage of the testicle has been reported to be 90% to 100%, but only 50% and 10% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively.3 The patient in this case was taken immediately for emergent surgical detorsion, and the left testicle was salvaged.

1. Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 1994;44 (1):114-116.

2. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1167.

3. Sharp VJ, Kieran K, Arlen AM. Testicular torsion: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(12):835-840.

4. Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: It is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:80Y86. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f5ed9.

5. Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):604-607.

6. Burks DD, Markey BJ, Burkhard TK, Balsara ZN, Haluszka MM, Canning DA. Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1990;175(3):815-821. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188301.

7. Aso C, Enríquez G, Fité M, et al. Gray-scale and color doppler sonography of scrotal disorders in children: an update. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1197-1214. doi:10.1148/rg.255045109.

8. Hadziselimovic F, Geneto R, Emmons LR. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J Urol. 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1158-1160.

1. Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 1994;44 (1):114-116.

2. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1167.

3. Sharp VJ, Kieran K, Arlen AM. Testicular torsion: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(12):835-840.

4. Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: It is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:80Y86. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f5ed9.

5. Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):604-607.

6. Burks DD, Markey BJ, Burkhard TK, Balsara ZN, Haluszka MM, Canning DA. Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1990;175(3):815-821. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188301.

7. Aso C, Enríquez G, Fité M, et al. Gray-scale and color doppler sonography of scrotal disorders in children: an update. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1197-1214. doi:10.1148/rg.255045109.

8. Hadziselimovic F, Geneto R, Emmons LR. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J Urol. 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1158-1160.