User login

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) faced—and failed—an important test on October 1, 2013, when open enrollment began in the new health-care marketplaces. Plenty has been written about Web site crashes, technical glitches, and what seems to be general mismanagement of this crucial aspect of implementation.

Let’s look behind the headlines to see which aspects of the ACA are working, and which aren’t, and why.

KNOWING THE FACTS CAN HELP YOU HELP YOUR PATIENTS

ObGyns are scientists. As a scientist, you know the importance of facts. In your research and clinical care, you seek out and rely on scientific facts and evidence. You leave aside unsubstantiated thinking.

It’s imperative that we take the same approach with this subject. Far too many misleading and unsubstantiated claims and headlines are crowding out reliable factual information, seriously hindering physicians’ ability to understand this important health-care system change and respond to it appropriately on behalf of patients. As much as we all love Facebook, for example, it may not be the most accurate source of information on the ACA.

Plenty of reliable, factual, unbiased sources of information about the ACA exist, such as “Understanding Obamacare, Politico’s Guide to the Affordable Care Act” (http://www.politico.com/obamacare-guide/). Other helpful sources of ACA outreach and enrollment information:

HealthCare.gov is the federal government’s main portal for information on the Affordable Care Act. A Spanish version of this site can be accessed at www.CuidadoDeSalud.gov.

“FAQ: What you need to know about the new online marketplaces” features questions and answers from Kaiser Health News at http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2013/september/17/marketplace-faq-insurance-exchange-obamacare-aca.aspx.

“Fact sheets: Why the Affordable Care Act matters for women” offers links to summaries of ACA provisions; information on health care for pregnant, low-income and older women; preventive care; and more from the National Partnership for Women and Families at http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=issues_health_reform_anniversary.

Webinars, speakers, FAQs, and more from Doctors for America at http://www.drsforamerica.org/take-action/get-people-covered.

Reports, blog posts, and links to information on enrollment from Enroll America at www.enrollamerica.org.

An informative video on coverage decisions from the Kaiser Family Foundation at http://kff.org/health-reform/video/youtoons-obamacare-video/.

A REVIEW OF THE CHANGES UNDER ACA

Let’s start with one key fact: The ACA offers a lot of good for women’s health care. Many of these improvements hinge on individuals’ ability to enroll in private health insurance policies sold in the marketplaces.

Each state’s marketplace is similar to the system used by the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), the insurance marketplace used nationwide by federal employees, including members of Congress. Private plans, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Aetna, and United Healthcare, offer health insurance on the FEHBP marketplace to the millions of federal employees each year.

In state marketplaces, private health insurers will offer plans to potentially millions of previously under- or uninsured individuals and families. In exchange for access to this huge new group of consumers, private insurers must abide by a number of important consumer protections in order to be eligible to sell their policies in a state marketplace:

Insurers must agree to abide by the 80/20 rule. Under this game-changer, insurers agree to return the actuarial value of 80% of an enrollee’s premium to health care, keeping only a maximum of 20% for profits and other non-health-care categories.

Insurers must agree to cover 10 essential benefits, including maternity care.

Insurers must agree to cover key preventive services, without copays or deductibles, helping our patients stay healthy.

Insurers must abide by significant insurance protections. They can’t, for example, deny a woman coverage because she has a preexisting condition, was once the victim of domestic violence, or once had a cesarean delivery.

Essential benefits and preventive services

All private health insurance plans sold in the state marketplaces must cover the 10 essential health benefits:

ambulatory patient services

emergency services

hospitalization

maternity and newborn care

mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment

prescription drugs

rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

laboratory services

preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

These insurers also must cover—with no charge to the patient—preventive services:

well-woman visits (one or more)

all FDA-approved contraceptive methods and contraception counseling

gestational diabetes screening

mammograms

Pap tests

HIV and other sexually transmitted infection screening and counseling

breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling

domestic violence screening and counseling.

Related Article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

In addition, private insurers must offer additional preventive services, although they can charge copays for them:

anemia screening on a routine basis for pregnant women

screening for urinary tract or other infection for pregnant women

counseling about genetic testing for a BRCA mutation for women at higher risk

counseling about chemoprevention of breast cancer for women at higher risk

cervical cancer screening for sexually active women

folic acid supplementation for women who may become pregnant

osteoporosis screening for women over age 60, depending on risk factors

screening for Rh incompatibility for all pregnant women and follow-up testing for women at higher risk

tobacco use screening and interventions for all women, and expanded counseling for pregnant users of tobacco.

An end to preexisting-condition exclusions and other harmful practices

Insurers offering plans in the state marketplaces also must abide by important insurance reforms:

They must eliminate exclusions for preexisting conditions. Insurers cannot deny individuals coverage because they already have a condition that requires medical care, including pregnancy. Before this ACA rule, private insurers often rejected applicants who needed care, as well as those who accessed health care in the past. Insurers regularly denied coverage to women who had had a cesarean delivery or had once been a victim of domestic violence.

They cannot charge women more than men for the same coverage. Before the ACA, women seeking health-care coverage often faced higher premiums than men for identical coverage. This made private coverage less affordable for our patients.

They cannot impose a 9-month waiting period. (Need I say more?)

They must eliminate any annual lifetime limits on coverage. Insurers selling policies in the marketplaces cannot end coverage after a certain dollar amount has been reached, a common practice before the ACA. This change is good news for you and your patients. A patient needing long or expensive care won’t lose coverage when the cost of her care hits an arbitrary ceiling.

They cannot rescind coverage unless fraud is proven. Before the ACA, private health insurers would often drop an individual if he or she started racking up high health-care costs. Patients in the middle of expensive cancer treatments, for example, would find themselves suddenly without health insurance. This won’t happen for policies sold in marketplaces unless the patient lied on her enrollment forms or failed to keep up her premium payments.

What these changes mean, in real numbers

These protections are critically important to your ability to care for your patients. Here’s what they mean in real life:

Health-care coverage for about 10,000 insured women is no longer subject to an annual lifetime coverage limit.

Private insurers can’t drop coverage, a change that will affect about 5.5 million insured women.

Insurance companies cannot deny coverage for preexisting conditions, which will help insure about 100,000 women.

Each state marketplace offers four types of plans, the idea being to help people compare policies side by side. All plans sold in the marketplaces must abide by the consumer protections I just reviewed. Each tier is differentiated by the average percentage of an enrollee’s health-care expenses paid by the insurer. The more an enrollee agrees to pay out of pocket, the lower his or her premium.

The tiers are:

Bronze – The insurer covers 60% of health-care costs, and the insured covers 40%. This tier offers the cheapest premiums.

Silver – The insurer covers 70% of costs.

Gold – The insurer covers 80% of costs.

Platinum – The insurer covers 90% of costs.

WHAT WENT WRONG

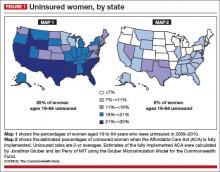

If everything had gone according to plan, women’s access to health insurance would have increased dramatically nationwide, including in the dark blue states in FIGURE 1 (Map 1)—states that rank lowest in access to care. You’ll notice that many of the states that are dark blue in Map 1 shift to light blue in Map 2. Take a careful look at those dark blue states and see what colors they are in the next two maps (FIGURES 1 and 2). Hint: There’s a pattern.

Problem 1 – Strains on Healthcare.gov

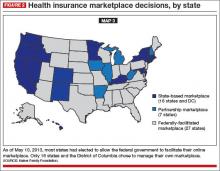

When the ACA was signed into law, most states were expected to build and run their own online marketplaces. The federal government offered to run a state exchange if a state didn’t. Few ACA engineers anticipated that the federal government would have to run the marketplaces in more than half the states—politics-fueled decisions in many states. Now you can see that many of the states that are dark blue in Map 1 are gray in Map 3 (FIGURE 2). Many states whose populations have the greatest need left it to the federal government to run the marketplaces.

Data indicate that state-run marketplaces are doing pretty well—a fact not often caught in frenzied headlines. If we look at the percentage of the target population actually enrolled in marketplace insurance plans during the first month, we see that the lowest state marketplace enrollment was in Washington State, with 30% of its target population enrolled. The highest target-population enrollment was achieved in Connecticut, with 191%.

Compare these numbers to the rates of target-population enrollment in states with marketplaces run by the federal government, which range from 3% to 20% (FIGURE 2). During the first month, federal and state-run marketplaces together enrolled 106,000 individuals into new coverage, 21% of the national target.

The news media have focused on the federal online enrollment debacle. Easier enrollment options are available to people who live in federally run marketplace states, including direct enrollment. Strongly supported by America’s health insurance industry, direct enrollment lets potential enrollees purchase coverage directly from insurance companies participating in the marketplaces.

Problem 2: People lost their current coverage

This is a problem worth exploring—one that affects people who previously bought insurance on the individual insurance market. This is the market that offers people comparatively limited coverage, usually with no maternity care coverage, for comparatively high premiums.

So why are these individuals losing coverage?

They are losing coverage because, as of January 2014, new individual plans must abide by the 80/20 rule, abide by insurance protections, and cover 10 essential services with no cost sharing.

You may recall that, in August 2009, Americans were demanding that they be able to keep the health-care coverage they currently had, and President Barack Obama promised that they would be able to. Consequently, health insurance policies in effect before March 2010, when the ACA was signed into law, were exempted—“grandfathered”—from most ACA requirements. If people liked their old policies, they could keep them.

Grandfathered plans are exempt from:

the requirement to cover the 10 essential health benefits

the requirement that plans must provide preventive services with no patient cost sharing

state or federal review of insurance premium increases of 10% or more for non-group and small business plans

a rule allowing consumers to appeal denials of claims to a third-party reviewer.

Most ACA requirements apply to new policies—those offered after March 2010 and those that have been changed significantly by the insurance companies. Some examples of changes in coverage that would cause a plan to lose grandfathering include:

the elimination of benefits to diagnose or treat a particular condition

an increase in the up-front deductible patients must pay before coverage kicks in by more than the cumulative growth in medical inflation since March 2010 plus 15%

a reduction in the share of the premium that the employer pays by more than 5% since March 2010.

How many people are we talking about? Not the 40% of Americans who have employer-based coverage or the 20% of Americans on Medicare, Medicaid, or Tricare. This provision affects about 5% of the insured, as many as 15 million people—many with plans that offer little coverage for high premiums.

The ACA intention was that many people previously covered in the individual insurance market would find better and cheaper coverage in their state marketplaces. That may be a good option for people in states that have chosen to run their own marketplaces, and a good option for people in other states, too, as federal online enrollment issues get fixed.

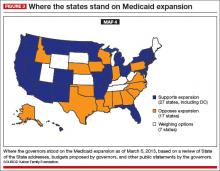

Problem 3: Medicaid expansion became a state option

When the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate, it also effectively turned the ACA Medicaid expansion into a state option.

Think of the Medicaid expansion as Medicaid Part 2. Regular Medicaid remains largely unchanged, with the same eligibility rules and coverage requirements.

The ACA included a provision under which every state would add a new part to its Medicaid program. Beginning in 2014, this part—the expansion—would cover individuals in each state with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty line—about $32,000 for a family of four in 2014. Medicaid expansion coverage is based only on income eligibility, a major change for women, many of whom currently qualify for Medicaid only if they’re pregnant.

Who would pay for the new coverage?

In 2014, 2015, and 2016, the federal government pays 100% of the cost of care for Medicaid expansion. From 2017 to 2020, the federal share gradually drops to 90%.

Medicaid expansion is an integral part of reducing the number of uninsured under the ACA and is expected to reduce the uninsured rate by almost 30% if adopted by every state. Medicaid expansion plus the ACA marketplaces were expected to cut our uninsured rate almost in half.

FIGURE 3 shows how states responded when the Supreme Court effectively converted the Medicaid expansion into an option, leaving us, again, with coverage gaps. Many of the states that have opted not to expand Medicaid are the same states that declined to operate their own state marketplaces, the same states with highest percentages of the uninsured.

The ACA has many interdependent parts. Make the Medicaid expansion a state option, and you end up with higher than expected rates of uninsured. Trigger big changes in the individual market when there are still bugs in the system, and people are left in the lurch.

Related Article: ACOG to legislators: Partnership, not interference Lucia DiVenere, MA (April 2013)

What’s happening now

As this article is going to press, enrollment in the marketplaces is getting easier, with Web site fixes and useful alternatives to Web-based enrollment. Small changes are being made to some deadlines to help people who have gotten stuck in the process. We’ll likely continue to see steps forward and back over the next many months.

Two things remain important:

We need to stick with the facts. If you see something in the news that seems too crazy to be real, your hunch may be right.

Your patients can benefit significantly from the ACA. An ACOG Fellow recently told me about one of his patients who has a severe health condition, no insurance, and needs expensive treatment. The ACA, with its marketplace rules outlawing exclusions for preexisting conditions and offering premium assistance, may be a lifesaver to her. But first she needs to enroll.

As your patients’ trusted physician, you can help point them in the right direction, possibly toward coverage that they never had before.

That’s good for all of us.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) faced—and failed—an important test on October 1, 2013, when open enrollment began in the new health-care marketplaces. Plenty has been written about Web site crashes, technical glitches, and what seems to be general mismanagement of this crucial aspect of implementation.

Let’s look behind the headlines to see which aspects of the ACA are working, and which aren’t, and why.

KNOWING THE FACTS CAN HELP YOU HELP YOUR PATIENTS

ObGyns are scientists. As a scientist, you know the importance of facts. In your research and clinical care, you seek out and rely on scientific facts and evidence. You leave aside unsubstantiated thinking.

It’s imperative that we take the same approach with this subject. Far too many misleading and unsubstantiated claims and headlines are crowding out reliable factual information, seriously hindering physicians’ ability to understand this important health-care system change and respond to it appropriately on behalf of patients. As much as we all love Facebook, for example, it may not be the most accurate source of information on the ACA.

Plenty of reliable, factual, unbiased sources of information about the ACA exist, such as “Understanding Obamacare, Politico’s Guide to the Affordable Care Act” (http://www.politico.com/obamacare-guide/). Other helpful sources of ACA outreach and enrollment information:

HealthCare.gov is the federal government’s main portal for information on the Affordable Care Act. A Spanish version of this site can be accessed at www.CuidadoDeSalud.gov.

“FAQ: What you need to know about the new online marketplaces” features questions and answers from Kaiser Health News at http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2013/september/17/marketplace-faq-insurance-exchange-obamacare-aca.aspx.

“Fact sheets: Why the Affordable Care Act matters for women” offers links to summaries of ACA provisions; information on health care for pregnant, low-income and older women; preventive care; and more from the National Partnership for Women and Families at http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=issues_health_reform_anniversary.

Webinars, speakers, FAQs, and more from Doctors for America at http://www.drsforamerica.org/take-action/get-people-covered.

Reports, blog posts, and links to information on enrollment from Enroll America at www.enrollamerica.org.

An informative video on coverage decisions from the Kaiser Family Foundation at http://kff.org/health-reform/video/youtoons-obamacare-video/.

A REVIEW OF THE CHANGES UNDER ACA

Let’s start with one key fact: The ACA offers a lot of good for women’s health care. Many of these improvements hinge on individuals’ ability to enroll in private health insurance policies sold in the marketplaces.

Each state’s marketplace is similar to the system used by the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), the insurance marketplace used nationwide by federal employees, including members of Congress. Private plans, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Aetna, and United Healthcare, offer health insurance on the FEHBP marketplace to the millions of federal employees each year.

In state marketplaces, private health insurers will offer plans to potentially millions of previously under- or uninsured individuals and families. In exchange for access to this huge new group of consumers, private insurers must abide by a number of important consumer protections in order to be eligible to sell their policies in a state marketplace:

Insurers must agree to abide by the 80/20 rule. Under this game-changer, insurers agree to return the actuarial value of 80% of an enrollee’s premium to health care, keeping only a maximum of 20% for profits and other non-health-care categories.

Insurers must agree to cover 10 essential benefits, including maternity care.

Insurers must agree to cover key preventive services, without copays or deductibles, helping our patients stay healthy.

Insurers must abide by significant insurance protections. They can’t, for example, deny a woman coverage because she has a preexisting condition, was once the victim of domestic violence, or once had a cesarean delivery.

Essential benefits and preventive services

All private health insurance plans sold in the state marketplaces must cover the 10 essential health benefits:

ambulatory patient services

emergency services

hospitalization

maternity and newborn care

mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment

prescription drugs

rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

laboratory services

preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

These insurers also must cover—with no charge to the patient—preventive services:

well-woman visits (one or more)

all FDA-approved contraceptive methods and contraception counseling

gestational diabetes screening

mammograms

Pap tests

HIV and other sexually transmitted infection screening and counseling

breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling

domestic violence screening and counseling.

Related Article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

In addition, private insurers must offer additional preventive services, although they can charge copays for them:

anemia screening on a routine basis for pregnant women

screening for urinary tract or other infection for pregnant women

counseling about genetic testing for a BRCA mutation for women at higher risk

counseling about chemoprevention of breast cancer for women at higher risk

cervical cancer screening for sexually active women

folic acid supplementation for women who may become pregnant

osteoporosis screening for women over age 60, depending on risk factors

screening for Rh incompatibility for all pregnant women and follow-up testing for women at higher risk

tobacco use screening and interventions for all women, and expanded counseling for pregnant users of tobacco.

An end to preexisting-condition exclusions and other harmful practices

Insurers offering plans in the state marketplaces also must abide by important insurance reforms:

They must eliminate exclusions for preexisting conditions. Insurers cannot deny individuals coverage because they already have a condition that requires medical care, including pregnancy. Before this ACA rule, private insurers often rejected applicants who needed care, as well as those who accessed health care in the past. Insurers regularly denied coverage to women who had had a cesarean delivery or had once been a victim of domestic violence.

They cannot charge women more than men for the same coverage. Before the ACA, women seeking health-care coverage often faced higher premiums than men for identical coverage. This made private coverage less affordable for our patients.

They cannot impose a 9-month waiting period. (Need I say more?)

They must eliminate any annual lifetime limits on coverage. Insurers selling policies in the marketplaces cannot end coverage after a certain dollar amount has been reached, a common practice before the ACA. This change is good news for you and your patients. A patient needing long or expensive care won’t lose coverage when the cost of her care hits an arbitrary ceiling.

They cannot rescind coverage unless fraud is proven. Before the ACA, private health insurers would often drop an individual if he or she started racking up high health-care costs. Patients in the middle of expensive cancer treatments, for example, would find themselves suddenly without health insurance. This won’t happen for policies sold in marketplaces unless the patient lied on her enrollment forms or failed to keep up her premium payments.

What these changes mean, in real numbers

These protections are critically important to your ability to care for your patients. Here’s what they mean in real life:

Health-care coverage for about 10,000 insured women is no longer subject to an annual lifetime coverage limit.

Private insurers can’t drop coverage, a change that will affect about 5.5 million insured women.

Insurance companies cannot deny coverage for preexisting conditions, which will help insure about 100,000 women.

Each state marketplace offers four types of plans, the idea being to help people compare policies side by side. All plans sold in the marketplaces must abide by the consumer protections I just reviewed. Each tier is differentiated by the average percentage of an enrollee’s health-care expenses paid by the insurer. The more an enrollee agrees to pay out of pocket, the lower his or her premium.

The tiers are:

Bronze – The insurer covers 60% of health-care costs, and the insured covers 40%. This tier offers the cheapest premiums.

Silver – The insurer covers 70% of costs.

Gold – The insurer covers 80% of costs.

Platinum – The insurer covers 90% of costs.

WHAT WENT WRONG

If everything had gone according to plan, women’s access to health insurance would have increased dramatically nationwide, including in the dark blue states in FIGURE 1 (Map 1)—states that rank lowest in access to care. You’ll notice that many of the states that are dark blue in Map 1 shift to light blue in Map 2. Take a careful look at those dark blue states and see what colors they are in the next two maps (FIGURES 1 and 2). Hint: There’s a pattern.

Problem 1 – Strains on Healthcare.gov

When the ACA was signed into law, most states were expected to build and run their own online marketplaces. The federal government offered to run a state exchange if a state didn’t. Few ACA engineers anticipated that the federal government would have to run the marketplaces in more than half the states—politics-fueled decisions in many states. Now you can see that many of the states that are dark blue in Map 1 are gray in Map 3 (FIGURE 2). Many states whose populations have the greatest need left it to the federal government to run the marketplaces.

Data indicate that state-run marketplaces are doing pretty well—a fact not often caught in frenzied headlines. If we look at the percentage of the target population actually enrolled in marketplace insurance plans during the first month, we see that the lowest state marketplace enrollment was in Washington State, with 30% of its target population enrolled. The highest target-population enrollment was achieved in Connecticut, with 191%.

Compare these numbers to the rates of target-population enrollment in states with marketplaces run by the federal government, which range from 3% to 20% (FIGURE 2). During the first month, federal and state-run marketplaces together enrolled 106,000 individuals into new coverage, 21% of the national target.

The news media have focused on the federal online enrollment debacle. Easier enrollment options are available to people who live in federally run marketplace states, including direct enrollment. Strongly supported by America’s health insurance industry, direct enrollment lets potential enrollees purchase coverage directly from insurance companies participating in the marketplaces.

Problem 2: People lost their current coverage

This is a problem worth exploring—one that affects people who previously bought insurance on the individual insurance market. This is the market that offers people comparatively limited coverage, usually with no maternity care coverage, for comparatively high premiums.

So why are these individuals losing coverage?

They are losing coverage because, as of January 2014, new individual plans must abide by the 80/20 rule, abide by insurance protections, and cover 10 essential services with no cost sharing.

You may recall that, in August 2009, Americans were demanding that they be able to keep the health-care coverage they currently had, and President Barack Obama promised that they would be able to. Consequently, health insurance policies in effect before March 2010, when the ACA was signed into law, were exempted—“grandfathered”—from most ACA requirements. If people liked their old policies, they could keep them.

Grandfathered plans are exempt from:

the requirement to cover the 10 essential health benefits

the requirement that plans must provide preventive services with no patient cost sharing

state or federal review of insurance premium increases of 10% or more for non-group and small business plans

a rule allowing consumers to appeal denials of claims to a third-party reviewer.

Most ACA requirements apply to new policies—those offered after March 2010 and those that have been changed significantly by the insurance companies. Some examples of changes in coverage that would cause a plan to lose grandfathering include:

the elimination of benefits to diagnose or treat a particular condition

an increase in the up-front deductible patients must pay before coverage kicks in by more than the cumulative growth in medical inflation since March 2010 plus 15%

a reduction in the share of the premium that the employer pays by more than 5% since March 2010.

How many people are we talking about? Not the 40% of Americans who have employer-based coverage or the 20% of Americans on Medicare, Medicaid, or Tricare. This provision affects about 5% of the insured, as many as 15 million people—many with plans that offer little coverage for high premiums.

The ACA intention was that many people previously covered in the individual insurance market would find better and cheaper coverage in their state marketplaces. That may be a good option for people in states that have chosen to run their own marketplaces, and a good option for people in other states, too, as federal online enrollment issues get fixed.

Problem 3: Medicaid expansion became a state option

When the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate, it also effectively turned the ACA Medicaid expansion into a state option.

Think of the Medicaid expansion as Medicaid Part 2. Regular Medicaid remains largely unchanged, with the same eligibility rules and coverage requirements.

The ACA included a provision under which every state would add a new part to its Medicaid program. Beginning in 2014, this part—the expansion—would cover individuals in each state with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty line—about $32,000 for a family of four in 2014. Medicaid expansion coverage is based only on income eligibility, a major change for women, many of whom currently qualify for Medicaid only if they’re pregnant.

Who would pay for the new coverage?

In 2014, 2015, and 2016, the federal government pays 100% of the cost of care for Medicaid expansion. From 2017 to 2020, the federal share gradually drops to 90%.

Medicaid expansion is an integral part of reducing the number of uninsured under the ACA and is expected to reduce the uninsured rate by almost 30% if adopted by every state. Medicaid expansion plus the ACA marketplaces were expected to cut our uninsured rate almost in half.

FIGURE 3 shows how states responded when the Supreme Court effectively converted the Medicaid expansion into an option, leaving us, again, with coverage gaps. Many of the states that have opted not to expand Medicaid are the same states that declined to operate their own state marketplaces, the same states with highest percentages of the uninsured.

The ACA has many interdependent parts. Make the Medicaid expansion a state option, and you end up with higher than expected rates of uninsured. Trigger big changes in the individual market when there are still bugs in the system, and people are left in the lurch.

Related Article: ACOG to legislators: Partnership, not interference Lucia DiVenere, MA (April 2013)

What’s happening now

As this article is going to press, enrollment in the marketplaces is getting easier, with Web site fixes and useful alternatives to Web-based enrollment. Small changes are being made to some deadlines to help people who have gotten stuck in the process. We’ll likely continue to see steps forward and back over the next many months.

Two things remain important:

We need to stick with the facts. If you see something in the news that seems too crazy to be real, your hunch may be right.

Your patients can benefit significantly from the ACA. An ACOG Fellow recently told me about one of his patients who has a severe health condition, no insurance, and needs expensive treatment. The ACA, with its marketplace rules outlawing exclusions for preexisting conditions and offering premium assistance, may be a lifesaver to her. But first she needs to enroll.

As your patients’ trusted physician, you can help point them in the right direction, possibly toward coverage that they never had before.

That’s good for all of us.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) faced—and failed—an important test on October 1, 2013, when open enrollment began in the new health-care marketplaces. Plenty has been written about Web site crashes, technical glitches, and what seems to be general mismanagement of this crucial aspect of implementation.

Let’s look behind the headlines to see which aspects of the ACA are working, and which aren’t, and why.

KNOWING THE FACTS CAN HELP YOU HELP YOUR PATIENTS

ObGyns are scientists. As a scientist, you know the importance of facts. In your research and clinical care, you seek out and rely on scientific facts and evidence. You leave aside unsubstantiated thinking.

It’s imperative that we take the same approach with this subject. Far too many misleading and unsubstantiated claims and headlines are crowding out reliable factual information, seriously hindering physicians’ ability to understand this important health-care system change and respond to it appropriately on behalf of patients. As much as we all love Facebook, for example, it may not be the most accurate source of information on the ACA.

Plenty of reliable, factual, unbiased sources of information about the ACA exist, such as “Understanding Obamacare, Politico’s Guide to the Affordable Care Act” (http://www.politico.com/obamacare-guide/). Other helpful sources of ACA outreach and enrollment information:

HealthCare.gov is the federal government’s main portal for information on the Affordable Care Act. A Spanish version of this site can be accessed at www.CuidadoDeSalud.gov.

“FAQ: What you need to know about the new online marketplaces” features questions and answers from Kaiser Health News at http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2013/september/17/marketplace-faq-insurance-exchange-obamacare-aca.aspx.

“Fact sheets: Why the Affordable Care Act matters for women” offers links to summaries of ACA provisions; information on health care for pregnant, low-income and older women; preventive care; and more from the National Partnership for Women and Families at http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=issues_health_reform_anniversary.

Webinars, speakers, FAQs, and more from Doctors for America at http://www.drsforamerica.org/take-action/get-people-covered.

Reports, blog posts, and links to information on enrollment from Enroll America at www.enrollamerica.org.

An informative video on coverage decisions from the Kaiser Family Foundation at http://kff.org/health-reform/video/youtoons-obamacare-video/.

A REVIEW OF THE CHANGES UNDER ACA

Let’s start with one key fact: The ACA offers a lot of good for women’s health care. Many of these improvements hinge on individuals’ ability to enroll in private health insurance policies sold in the marketplaces.

Each state’s marketplace is similar to the system used by the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), the insurance marketplace used nationwide by federal employees, including members of Congress. Private plans, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Aetna, and United Healthcare, offer health insurance on the FEHBP marketplace to the millions of federal employees each year.

In state marketplaces, private health insurers will offer plans to potentially millions of previously under- or uninsured individuals and families. In exchange for access to this huge new group of consumers, private insurers must abide by a number of important consumer protections in order to be eligible to sell their policies in a state marketplace:

Insurers must agree to abide by the 80/20 rule. Under this game-changer, insurers agree to return the actuarial value of 80% of an enrollee’s premium to health care, keeping only a maximum of 20% for profits and other non-health-care categories.

Insurers must agree to cover 10 essential benefits, including maternity care.

Insurers must agree to cover key preventive services, without copays or deductibles, helping our patients stay healthy.

Insurers must abide by significant insurance protections. They can’t, for example, deny a woman coverage because she has a preexisting condition, was once the victim of domestic violence, or once had a cesarean delivery.

Essential benefits and preventive services

All private health insurance plans sold in the state marketplaces must cover the 10 essential health benefits:

ambulatory patient services

emergency services

hospitalization

maternity and newborn care

mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment

prescription drugs

rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

laboratory services

preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

These insurers also must cover—with no charge to the patient—preventive services:

well-woman visits (one or more)

all FDA-approved contraceptive methods and contraception counseling

gestational diabetes screening

mammograms

Pap tests

HIV and other sexually transmitted infection screening and counseling

breastfeeding support, supplies, and counseling

domestic violence screening and counseling.

Related Article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

In addition, private insurers must offer additional preventive services, although they can charge copays for them:

anemia screening on a routine basis for pregnant women

screening for urinary tract or other infection for pregnant women

counseling about genetic testing for a BRCA mutation for women at higher risk

counseling about chemoprevention of breast cancer for women at higher risk

cervical cancer screening for sexually active women

folic acid supplementation for women who may become pregnant

osteoporosis screening for women over age 60, depending on risk factors

screening for Rh incompatibility for all pregnant women and follow-up testing for women at higher risk

tobacco use screening and interventions for all women, and expanded counseling for pregnant users of tobacco.

An end to preexisting-condition exclusions and other harmful practices

Insurers offering plans in the state marketplaces also must abide by important insurance reforms:

They must eliminate exclusions for preexisting conditions. Insurers cannot deny individuals coverage because they already have a condition that requires medical care, including pregnancy. Before this ACA rule, private insurers often rejected applicants who needed care, as well as those who accessed health care in the past. Insurers regularly denied coverage to women who had had a cesarean delivery or had once been a victim of domestic violence.

They cannot charge women more than men for the same coverage. Before the ACA, women seeking health-care coverage often faced higher premiums than men for identical coverage. This made private coverage less affordable for our patients.

They cannot impose a 9-month waiting period. (Need I say more?)

They must eliminate any annual lifetime limits on coverage. Insurers selling policies in the marketplaces cannot end coverage after a certain dollar amount has been reached, a common practice before the ACA. This change is good news for you and your patients. A patient needing long or expensive care won’t lose coverage when the cost of her care hits an arbitrary ceiling.

They cannot rescind coverage unless fraud is proven. Before the ACA, private health insurers would often drop an individual if he or she started racking up high health-care costs. Patients in the middle of expensive cancer treatments, for example, would find themselves suddenly without health insurance. This won’t happen for policies sold in marketplaces unless the patient lied on her enrollment forms or failed to keep up her premium payments.

What these changes mean, in real numbers

These protections are critically important to your ability to care for your patients. Here’s what they mean in real life:

Health-care coverage for about 10,000 insured women is no longer subject to an annual lifetime coverage limit.

Private insurers can’t drop coverage, a change that will affect about 5.5 million insured women.

Insurance companies cannot deny coverage for preexisting conditions, which will help insure about 100,000 women.

Each state marketplace offers four types of plans, the idea being to help people compare policies side by side. All plans sold in the marketplaces must abide by the consumer protections I just reviewed. Each tier is differentiated by the average percentage of an enrollee’s health-care expenses paid by the insurer. The more an enrollee agrees to pay out of pocket, the lower his or her premium.

The tiers are:

Bronze – The insurer covers 60% of health-care costs, and the insured covers 40%. This tier offers the cheapest premiums.

Silver – The insurer covers 70% of costs.

Gold – The insurer covers 80% of costs.

Platinum – The insurer covers 90% of costs.

WHAT WENT WRONG

If everything had gone according to plan, women’s access to health insurance would have increased dramatically nationwide, including in the dark blue states in FIGURE 1 (Map 1)—states that rank lowest in access to care. You’ll notice that many of the states that are dark blue in Map 1 shift to light blue in Map 2. Take a careful look at those dark blue states and see what colors they are in the next two maps (FIGURES 1 and 2). Hint: There’s a pattern.

Problem 1 – Strains on Healthcare.gov

When the ACA was signed into law, most states were expected to build and run their own online marketplaces. The federal government offered to run a state exchange if a state didn’t. Few ACA engineers anticipated that the federal government would have to run the marketplaces in more than half the states—politics-fueled decisions in many states. Now you can see that many of the states that are dark blue in Map 1 are gray in Map 3 (FIGURE 2). Many states whose populations have the greatest need left it to the federal government to run the marketplaces.

Data indicate that state-run marketplaces are doing pretty well—a fact not often caught in frenzied headlines. If we look at the percentage of the target population actually enrolled in marketplace insurance plans during the first month, we see that the lowest state marketplace enrollment was in Washington State, with 30% of its target population enrolled. The highest target-population enrollment was achieved in Connecticut, with 191%.

Compare these numbers to the rates of target-population enrollment in states with marketplaces run by the federal government, which range from 3% to 20% (FIGURE 2). During the first month, federal and state-run marketplaces together enrolled 106,000 individuals into new coverage, 21% of the national target.

The news media have focused on the federal online enrollment debacle. Easier enrollment options are available to people who live in federally run marketplace states, including direct enrollment. Strongly supported by America’s health insurance industry, direct enrollment lets potential enrollees purchase coverage directly from insurance companies participating in the marketplaces.

Problem 2: People lost their current coverage

This is a problem worth exploring—one that affects people who previously bought insurance on the individual insurance market. This is the market that offers people comparatively limited coverage, usually with no maternity care coverage, for comparatively high premiums.

So why are these individuals losing coverage?

They are losing coverage because, as of January 2014, new individual plans must abide by the 80/20 rule, abide by insurance protections, and cover 10 essential services with no cost sharing.

You may recall that, in August 2009, Americans were demanding that they be able to keep the health-care coverage they currently had, and President Barack Obama promised that they would be able to. Consequently, health insurance policies in effect before March 2010, when the ACA was signed into law, were exempted—“grandfathered”—from most ACA requirements. If people liked their old policies, they could keep them.

Grandfathered plans are exempt from:

the requirement to cover the 10 essential health benefits

the requirement that plans must provide preventive services with no patient cost sharing

state or federal review of insurance premium increases of 10% or more for non-group and small business plans

a rule allowing consumers to appeal denials of claims to a third-party reviewer.

Most ACA requirements apply to new policies—those offered after March 2010 and those that have been changed significantly by the insurance companies. Some examples of changes in coverage that would cause a plan to lose grandfathering include:

the elimination of benefits to diagnose or treat a particular condition

an increase in the up-front deductible patients must pay before coverage kicks in by more than the cumulative growth in medical inflation since March 2010 plus 15%

a reduction in the share of the premium that the employer pays by more than 5% since March 2010.

How many people are we talking about? Not the 40% of Americans who have employer-based coverage or the 20% of Americans on Medicare, Medicaid, or Tricare. This provision affects about 5% of the insured, as many as 15 million people—many with plans that offer little coverage for high premiums.

The ACA intention was that many people previously covered in the individual insurance market would find better and cheaper coverage in their state marketplaces. That may be a good option for people in states that have chosen to run their own marketplaces, and a good option for people in other states, too, as federal online enrollment issues get fixed.

Problem 3: Medicaid expansion became a state option

When the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate, it also effectively turned the ACA Medicaid expansion into a state option.

Think of the Medicaid expansion as Medicaid Part 2. Regular Medicaid remains largely unchanged, with the same eligibility rules and coverage requirements.

The ACA included a provision under which every state would add a new part to its Medicaid program. Beginning in 2014, this part—the expansion—would cover individuals in each state with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty line—about $32,000 for a family of four in 2014. Medicaid expansion coverage is based only on income eligibility, a major change for women, many of whom currently qualify for Medicaid only if they’re pregnant.

Who would pay for the new coverage?

In 2014, 2015, and 2016, the federal government pays 100% of the cost of care for Medicaid expansion. From 2017 to 2020, the federal share gradually drops to 90%.

Medicaid expansion is an integral part of reducing the number of uninsured under the ACA and is expected to reduce the uninsured rate by almost 30% if adopted by every state. Medicaid expansion plus the ACA marketplaces were expected to cut our uninsured rate almost in half.

FIGURE 3 shows how states responded when the Supreme Court effectively converted the Medicaid expansion into an option, leaving us, again, with coverage gaps. Many of the states that have opted not to expand Medicaid are the same states that declined to operate their own state marketplaces, the same states with highest percentages of the uninsured.

The ACA has many interdependent parts. Make the Medicaid expansion a state option, and you end up with higher than expected rates of uninsured. Trigger big changes in the individual market when there are still bugs in the system, and people are left in the lurch.

Related Article: ACOG to legislators: Partnership, not interference Lucia DiVenere, MA (April 2013)

What’s happening now

As this article is going to press, enrollment in the marketplaces is getting easier, with Web site fixes and useful alternatives to Web-based enrollment. Small changes are being made to some deadlines to help people who have gotten stuck in the process. We’ll likely continue to see steps forward and back over the next many months.

Two things remain important:

We need to stick with the facts. If you see something in the news that seems too crazy to be real, your hunch may be right.

Your patients can benefit significantly from the ACA. An ACOG Fellow recently told me about one of his patients who has a severe health condition, no insurance, and needs expensive treatment. The ACA, with its marketplace rules outlawing exclusions for preexisting conditions and offering premium assistance, may be a lifesaver to her. But first she needs to enroll.

As your patients’ trusted physician, you can help point them in the right direction, possibly toward coverage that they never had before.

That’s good for all of us.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com