User login

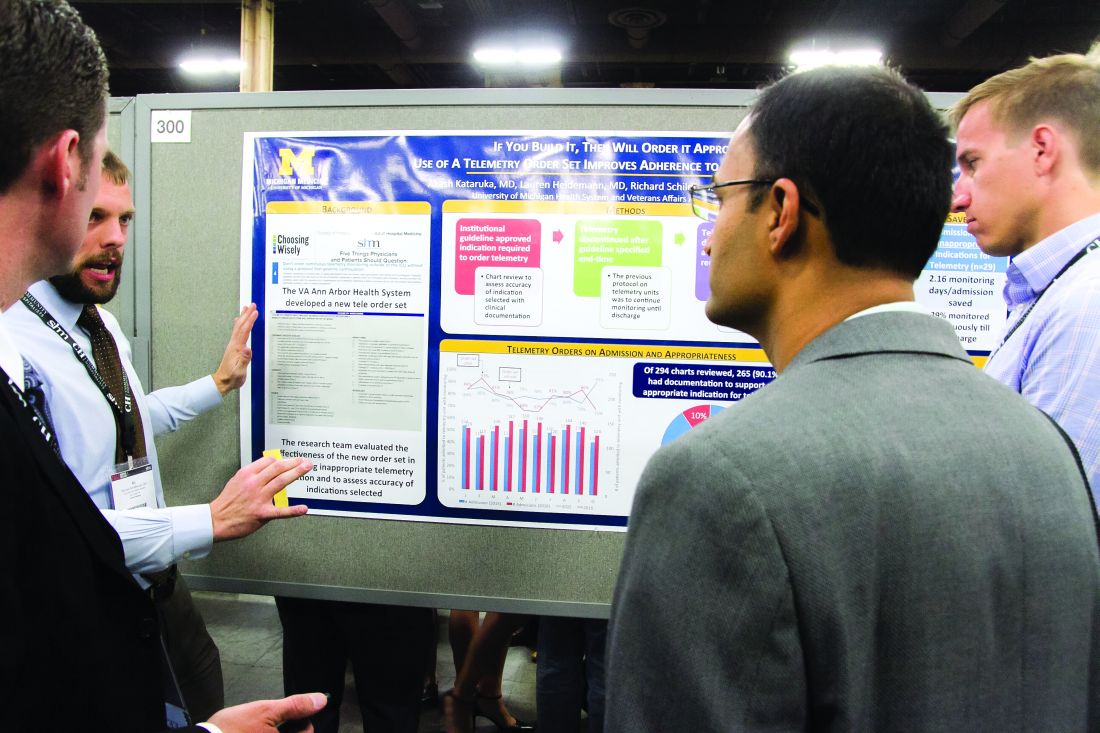

From idea to abstract, RIV posters highlight novel thinking

Masih Shinwa, MD, stood beside a half-circle of judges Tuesday night at SHM’s annual Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and argued why his entry, already a finalist, should win. And to think, his poster, “Please ‘THINK’ Before You Order: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Decreasing Overutilization of Daily Labs,” was born simply of a group of medical students who incredulously said they were amazed patients would be woken in the middle of the night for laboratory tests.

Eighteen months later, the poster drew hundreds of questions from passersby on how a team approach could help generate fewer labs and chemistry testing. Now, the work could serve as a potential guide for other hospitals seeking to reduce unnecessary tests, a focal point of SHM and the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

“This is a way to make it national,” he said. “You may have affected the lives of the patients in your hospital, but unless you attend these types of national meetings, it’s hard to get that perspective across [the country].”

That level of personal and professional collaboration is the purpose of the RIV, one of the best-attended events of SHM’s annual meeting. The event has become so popular that submissions this year tallied 1,712, nearly triple the number of submissions at the 2010 event.

“One of the amazing things is everyone has their own poster. They are doing their work,” said Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, the formal name for the poster contest. “But then they start up conversations with the people next to them. ... seeing the organic networking and the discussions that arise from that is really exciting. RIV really serves as a way of connecting people together who might not have known the other person was doing that kind of work.”

Dr. Shinwa said that the specialty’s focus on research is important. He said it positions the field to be leaders, not just for patient care, but for hospitals and institutions.

“We are physicians. Our role is taking care of patients,” he said. “[But] knowing that there are people who are not just focusing on taking care of specific patients, but are actually there to improve the entire system and the process, that is really gratifying.”

Masih Shinwa, MD, stood beside a half-circle of judges Tuesday night at SHM’s annual Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and argued why his entry, already a finalist, should win. And to think, his poster, “Please ‘THINK’ Before You Order: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Decreasing Overutilization of Daily Labs,” was born simply of a group of medical students who incredulously said they were amazed patients would be woken in the middle of the night for laboratory tests.

Eighteen months later, the poster drew hundreds of questions from passersby on how a team approach could help generate fewer labs and chemistry testing. Now, the work could serve as a potential guide for other hospitals seeking to reduce unnecessary tests, a focal point of SHM and the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

“This is a way to make it national,” he said. “You may have affected the lives of the patients in your hospital, but unless you attend these types of national meetings, it’s hard to get that perspective across [the country].”

That level of personal and professional collaboration is the purpose of the RIV, one of the best-attended events of SHM’s annual meeting. The event has become so popular that submissions this year tallied 1,712, nearly triple the number of submissions at the 2010 event.

“One of the amazing things is everyone has their own poster. They are doing their work,” said Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, the formal name for the poster contest. “But then they start up conversations with the people next to them. ... seeing the organic networking and the discussions that arise from that is really exciting. RIV really serves as a way of connecting people together who might not have known the other person was doing that kind of work.”

Dr. Shinwa said that the specialty’s focus on research is important. He said it positions the field to be leaders, not just for patient care, but for hospitals and institutions.

“We are physicians. Our role is taking care of patients,” he said. “[But] knowing that there are people who are not just focusing on taking care of specific patients, but are actually there to improve the entire system and the process, that is really gratifying.”

Masih Shinwa, MD, stood beside a half-circle of judges Tuesday night at SHM’s annual Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and argued why his entry, already a finalist, should win. And to think, his poster, “Please ‘THINK’ Before You Order: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Decreasing Overutilization of Daily Labs,” was born simply of a group of medical students who incredulously said they were amazed patients would be woken in the middle of the night for laboratory tests.

Eighteen months later, the poster drew hundreds of questions from passersby on how a team approach could help generate fewer labs and chemistry testing. Now, the work could serve as a potential guide for other hospitals seeking to reduce unnecessary tests, a focal point of SHM and the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign.

“This is a way to make it national,” he said. “You may have affected the lives of the patients in your hospital, but unless you attend these types of national meetings, it’s hard to get that perspective across [the country].”

That level of personal and professional collaboration is the purpose of the RIV, one of the best-attended events of SHM’s annual meeting. The event has become so popular that submissions this year tallied 1,712, nearly triple the number of submissions at the 2010 event.

“One of the amazing things is everyone has their own poster. They are doing their work,” said Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, program chair for HM17’s scientific abstracts competition, the formal name for the poster contest. “But then they start up conversations with the people next to them. ... seeing the organic networking and the discussions that arise from that is really exciting. RIV really serves as a way of connecting people together who might not have known the other person was doing that kind of work.”

Dr. Shinwa said that the specialty’s focus on research is important. He said it positions the field to be leaders, not just for patient care, but for hospitals and institutions.

“We are physicians. Our role is taking care of patients,” he said. “[But] knowing that there are people who are not just focusing on taking care of specific patients, but are actually there to improve the entire system and the process, that is really gratifying.”

VIDEO: Attaining the tools to start your own quality improvement project

Quality improvement at the program level is a major concern for most hospitalists. That’s exactly why Venkata Dontaraju, MD, MRCP, FHM, attended a Tuesday afternoon HM17 workshop entitled “Adding to Your Toolbox: QI Methodologies.”

Dr. Dontaraju, a hospitalist for 7 years with Rockford Health Physicians in Loves Park, Ill., wants to begin QI projects of his own. He planned to attend a number of QI-focused sessions at the annual meeting, with the toolbox session laying the foundation for such work.

“There is a lot of emphasis on cutting down the waste in health care, and also improving the processes,” he said. “That is where the role of QI comes into place. I want to do QI projects at my own hospital, but I first want to get the tools necessary for a successful project.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Quality improvement at the program level is a major concern for most hospitalists. That’s exactly why Venkata Dontaraju, MD, MRCP, FHM, attended a Tuesday afternoon HM17 workshop entitled “Adding to Your Toolbox: QI Methodologies.”

Dr. Dontaraju, a hospitalist for 7 years with Rockford Health Physicians in Loves Park, Ill., wants to begin QI projects of his own. He planned to attend a number of QI-focused sessions at the annual meeting, with the toolbox session laying the foundation for such work.

“There is a lot of emphasis on cutting down the waste in health care, and also improving the processes,” he said. “That is where the role of QI comes into place. I want to do QI projects at my own hospital, but I first want to get the tools necessary for a successful project.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Quality improvement at the program level is a major concern for most hospitalists. That’s exactly why Venkata Dontaraju, MD, MRCP, FHM, attended a Tuesday afternoon HM17 workshop entitled “Adding to Your Toolbox: QI Methodologies.”

Dr. Dontaraju, a hospitalist for 7 years with Rockford Health Physicians in Loves Park, Ill., wants to begin QI projects of his own. He planned to attend a number of QI-focused sessions at the annual meeting, with the toolbox session laying the foundation for such work.

“There is a lot of emphasis on cutting down the waste in health care, and also improving the processes,” he said. “That is where the role of QI comes into place. I want to do QI projects at my own hospital, but I first want to get the tools necessary for a successful project.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Forum focuses on forging Q.I. connections

Scrounging for information that could help her with quality improvement (Q.I.) projects, Charmaine Lewis, MD, MPH, the quality director with New Hanover Hospitalists in Wilmington, N.C., said she finds herself reviewing posters at the Annual Meeting and squinting at the images to see whether the electronic health records involved match the system she uses back home.

There’s got to be a better way.

Mangla Gulati, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and chief quality officer at the University of Maryland, and Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, led what grew into a lively, thoughtful discussion about ways for hospitalists to exchange information and to get support with Q.I. efforts at their centers.

The hospitalists who attended brought their experiences and their questions from a diverse range of centers, from Anchorage, Alaska, to southern California to Poughkeepsie, New York. They emphasized the need for easier access to initiatives that mirror what they are trying to do at their own centers, for more mentoring opportunities, and for more SHM chapters outside major metropolitan areas to help with networking. And they offered lessons on what they have already learned.

Remus Popa, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of California, Riverside, who has led Q.I. projects on the use of telemetry, said a successful project will likely be more than an idea that blooms inside the head of a hospitalist.

“We have to find something that the institution really needs,” Dr. Popa said. “You have to design a better fit with them. Otherwise, it’s going to be a tough conversation about resources, right?”

Esther Lee, MD, a hospitalist in Anchorage, Alaska, asked whether it might be possible for SHM to host a “mini-conference” specifically on quality improvement. At the Annual Meeting, she said, she often finds herself torn between attending Q.I. sessions and sessions on clinical topics.

SHM’s Goldstein said it was a possibility.

“It is something that we have talked about and will continue to talk about,” she said.

David Lucier, MD, MBA, MPH, Director of Quality and Safety for Hospital Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, said that emphasizing the safety aspect of a project can often help push it along.

“I find these [types of projects] to be quite compelling, at least in reordering the priority list,” he said.

Ms. Goldstein said the suggestions were helpful in SHM’s goal of creating a “culture of ‘quality enthusiasts.’”

“We want to be the home for quality for hospitalists,” she said. “So this input is really helpful for all of us in here.”

Scrounging for information that could help her with quality improvement (Q.I.) projects, Charmaine Lewis, MD, MPH, the quality director with New Hanover Hospitalists in Wilmington, N.C., said she finds herself reviewing posters at the Annual Meeting and squinting at the images to see whether the electronic health records involved match the system she uses back home.

There’s got to be a better way.

Mangla Gulati, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and chief quality officer at the University of Maryland, and Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, led what grew into a lively, thoughtful discussion about ways for hospitalists to exchange information and to get support with Q.I. efforts at their centers.

The hospitalists who attended brought their experiences and their questions from a diverse range of centers, from Anchorage, Alaska, to southern California to Poughkeepsie, New York. They emphasized the need for easier access to initiatives that mirror what they are trying to do at their own centers, for more mentoring opportunities, and for more SHM chapters outside major metropolitan areas to help with networking. And they offered lessons on what they have already learned.

Remus Popa, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of California, Riverside, who has led Q.I. projects on the use of telemetry, said a successful project will likely be more than an idea that blooms inside the head of a hospitalist.

“We have to find something that the institution really needs,” Dr. Popa said. “You have to design a better fit with them. Otherwise, it’s going to be a tough conversation about resources, right?”

Esther Lee, MD, a hospitalist in Anchorage, Alaska, asked whether it might be possible for SHM to host a “mini-conference” specifically on quality improvement. At the Annual Meeting, she said, she often finds herself torn between attending Q.I. sessions and sessions on clinical topics.

SHM’s Goldstein said it was a possibility.

“It is something that we have talked about and will continue to talk about,” she said.

David Lucier, MD, MBA, MPH, Director of Quality and Safety for Hospital Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, said that emphasizing the safety aspect of a project can often help push it along.

“I find these [types of projects] to be quite compelling, at least in reordering the priority list,” he said.

Ms. Goldstein said the suggestions were helpful in SHM’s goal of creating a “culture of ‘quality enthusiasts.’”

“We want to be the home for quality for hospitalists,” she said. “So this input is really helpful for all of us in here.”

Scrounging for information that could help her with quality improvement (Q.I.) projects, Charmaine Lewis, MD, MPH, the quality director with New Hanover Hospitalists in Wilmington, N.C., said she finds herself reviewing posters at the Annual Meeting and squinting at the images to see whether the electronic health records involved match the system she uses back home.

There’s got to be a better way.

Mangla Gulati, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and chief quality officer at the University of Maryland, and Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, led what grew into a lively, thoughtful discussion about ways for hospitalists to exchange information and to get support with Q.I. efforts at their centers.

The hospitalists who attended brought their experiences and their questions from a diverse range of centers, from Anchorage, Alaska, to southern California to Poughkeepsie, New York. They emphasized the need for easier access to initiatives that mirror what they are trying to do at their own centers, for more mentoring opportunities, and for more SHM chapters outside major metropolitan areas to help with networking. And they offered lessons on what they have already learned.

Remus Popa, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of California, Riverside, who has led Q.I. projects on the use of telemetry, said a successful project will likely be more than an idea that blooms inside the head of a hospitalist.

“We have to find something that the institution really needs,” Dr. Popa said. “You have to design a better fit with them. Otherwise, it’s going to be a tough conversation about resources, right?”

Esther Lee, MD, a hospitalist in Anchorage, Alaska, asked whether it might be possible for SHM to host a “mini-conference” specifically on quality improvement. At the Annual Meeting, she said, she often finds herself torn between attending Q.I. sessions and sessions on clinical topics.

SHM’s Goldstein said it was a possibility.

“It is something that we have talked about and will continue to talk about,” she said.

David Lucier, MD, MBA, MPH, Director of Quality and Safety for Hospital Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, said that emphasizing the safety aspect of a project can often help push it along.

“I find these [types of projects] to be quite compelling, at least in reordering the priority list,” he said.

Ms. Goldstein said the suggestions were helpful in SHM’s goal of creating a “culture of ‘quality enthusiasts.’”

“We want to be the home for quality for hospitalists,” she said. “So this input is really helpful for all of us in here.”

Proper UTI diagnosis, treatment relies on cautious approach

LAS VEGAS – Prudent use of catheters, cultures, and antibiotics are three keys to proper urinary tract diagnosis and management, according to a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We have not done very well with decreasing catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” said Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, an assistant professor of infectious disease medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and an infectious disease physician at MetroHealth Medical Center, where she is the medical director for infection prevention. “The main reason is people don’t really think of i

The main way to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections is to avoid catheters, she said, noting “that’s obvious, but unnecessary catheters get put in all the time.”

Dr. Hanrahan recommended only putting them in when absolutely necessary, doing so in a sterile manner, and then continually monitoring whether the patient still needs the catheter.

Knowing when to obtain a urine culture is key to ensuring proper diagnosing and treatment for UTIs. A person who is asymptomatic does not need a culture, Dr. Hanrahan said during the well-attended, rapid-fire session. Those who do need a culture include septic patients with no apparent cause for their symptomatic presentation, despite a careful history taking and physical exam. Also, patients with pelvic pain, or flank tenderness for whom no cause can otherwise be determined should be cultured. It is also appropriate to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria for pregnant patients, since it can be a sign of premature labor, and for patients about to undergo any invasive urologic procedure, Dr Hanrahan said.

“An awful lot of people have asymptomatic bacteriuria all the time,” she added, “and it doesn’t mean anything.”

Reasons to not culture include urine that smells “off” or that is cloudy or has sediment. “Anyone who has eaten asparagus knows that, after you eat it, your urine smells weird. It doesn’t mean you have a UTI,” she said.

She recommended against “pan culturing” in sepsis, and culturing “just because” when there is a clearly identifiable cause for the fever.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. Hanrahan urged physicians to avoid the overuse of antibiotics, suggesting that, whenever possible, the shortest possible course should be used. In order to help preserve antibiotic resistance, she also recommended using antibiotics that are not as prevalent, in order to help preserve antibiotic resistance. These could include nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin.

Dr. Hanrahan had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Prudent use of catheters, cultures, and antibiotics are three keys to proper urinary tract diagnosis and management, according to a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We have not done very well with decreasing catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” said Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, an assistant professor of infectious disease medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and an infectious disease physician at MetroHealth Medical Center, where she is the medical director for infection prevention. “The main reason is people don’t really think of i

The main way to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections is to avoid catheters, she said, noting “that’s obvious, but unnecessary catheters get put in all the time.”

Dr. Hanrahan recommended only putting them in when absolutely necessary, doing so in a sterile manner, and then continually monitoring whether the patient still needs the catheter.

Knowing when to obtain a urine culture is key to ensuring proper diagnosing and treatment for UTIs. A person who is asymptomatic does not need a culture, Dr. Hanrahan said during the well-attended, rapid-fire session. Those who do need a culture include septic patients with no apparent cause for their symptomatic presentation, despite a careful history taking and physical exam. Also, patients with pelvic pain, or flank tenderness for whom no cause can otherwise be determined should be cultured. It is also appropriate to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria for pregnant patients, since it can be a sign of premature labor, and for patients about to undergo any invasive urologic procedure, Dr Hanrahan said.

“An awful lot of people have asymptomatic bacteriuria all the time,” she added, “and it doesn’t mean anything.”

Reasons to not culture include urine that smells “off” or that is cloudy or has sediment. “Anyone who has eaten asparagus knows that, after you eat it, your urine smells weird. It doesn’t mean you have a UTI,” she said.

She recommended against “pan culturing” in sepsis, and culturing “just because” when there is a clearly identifiable cause for the fever.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. Hanrahan urged physicians to avoid the overuse of antibiotics, suggesting that, whenever possible, the shortest possible course should be used. In order to help preserve antibiotic resistance, she also recommended using antibiotics that are not as prevalent, in order to help preserve antibiotic resistance. These could include nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin.

Dr. Hanrahan had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Prudent use of catheters, cultures, and antibiotics are three keys to proper urinary tract diagnosis and management, according to a speaker at this year’s annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We have not done very well with decreasing catheter-associated urinary tract infections,” said Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, an assistant professor of infectious disease medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and an infectious disease physician at MetroHealth Medical Center, where she is the medical director for infection prevention. “The main reason is people don’t really think of i

The main way to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections is to avoid catheters, she said, noting “that’s obvious, but unnecessary catheters get put in all the time.”

Dr. Hanrahan recommended only putting them in when absolutely necessary, doing so in a sterile manner, and then continually monitoring whether the patient still needs the catheter.

Knowing when to obtain a urine culture is key to ensuring proper diagnosing and treatment for UTIs. A person who is asymptomatic does not need a culture, Dr. Hanrahan said during the well-attended, rapid-fire session. Those who do need a culture include septic patients with no apparent cause for their symptomatic presentation, despite a careful history taking and physical exam. Also, patients with pelvic pain, or flank tenderness for whom no cause can otherwise be determined should be cultured. It is also appropriate to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria for pregnant patients, since it can be a sign of premature labor, and for patients about to undergo any invasive urologic procedure, Dr Hanrahan said.

“An awful lot of people have asymptomatic bacteriuria all the time,” she added, “and it doesn’t mean anything.”

Reasons to not culture include urine that smells “off” or that is cloudy or has sediment. “Anyone who has eaten asparagus knows that, after you eat it, your urine smells weird. It doesn’t mean you have a UTI,” she said.

She recommended against “pan culturing” in sepsis, and culturing “just because” when there is a clearly identifiable cause for the fever.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. Hanrahan urged physicians to avoid the overuse of antibiotics, suggesting that, whenever possible, the shortest possible course should be used. In order to help preserve antibiotic resistance, she also recommended using antibiotics that are not as prevalent, in order to help preserve antibiotic resistance. These could include nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin.

Dr. Hanrahan had no relevant financial disclosures.

Hospitalists offer tips on QI projects

Anjala Tess, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, asked the audience how many of them had done a quality improvement project that had failed. It was not a time to be bashful: Almost half the hospitalists in the room admitted that it had happened to them.

Dr. Tess and Darlene Tad-y, MD, chair of the Physicians-in-Training Committee and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, were there to offer help in their session, “Adding to Your QI Toolbox.”

They highlighted three tools that they say are crucial to a project’s success: Creating a process map for clearly outlining how the project will work, interacting with stakeholders productively, and displaying data in a meaningful way.

Process mapping is a way of visualizing work or a process as distinct, ordered, and related steps, Dr. Tess said. Arranged on Post-It notes or written on a white board, the process should be one that can easily be updated. Seen objectively as a set of steps, it helps remove bias in how a process is viewed, she said.

“I would encourage you to do this on every QI project that you do where you are trying to accomplish something, because it makes a huge difference in understanding the work,” she said.

Stakeholder analysis – understanding the key people whose support could determine the success of the project – is also critical, she said. This can help get buy-in for the change, and it make a project stronger – and without it, you could doom your project, Dr. Tess said.

Doing this well involves understanding their financial and emotional interests, all the way down to whether they prefer face-to-face communication or e-mail, she said.

Then there’s the data. For it to matter, it must be presented well, and that requires context, Dr. Tad-y said.

“Data are just raw facts and figures,” she said. “Data are not the same as information.”

She suggested using run charts, in which data are plotted in some kind of order, usually chronological order. This kind of chart will typically include a median line, showing practice patterns before the QI project began, as well as a “goal line” to aim for, and notations on the timeline when changes were made, she said.

Others will be looking to the project manager for the meaning behind the data, she said.

“The story is going to come from you,” she said. “Otherwise, it’s just numbers.”

Anjala Tess, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, asked the audience how many of them had done a quality improvement project that had failed. It was not a time to be bashful: Almost half the hospitalists in the room admitted that it had happened to them.

Dr. Tess and Darlene Tad-y, MD, chair of the Physicians-in-Training Committee and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, were there to offer help in their session, “Adding to Your QI Toolbox.”

They highlighted three tools that they say are crucial to a project’s success: Creating a process map for clearly outlining how the project will work, interacting with stakeholders productively, and displaying data in a meaningful way.

Process mapping is a way of visualizing work or a process as distinct, ordered, and related steps, Dr. Tess said. Arranged on Post-It notes or written on a white board, the process should be one that can easily be updated. Seen objectively as a set of steps, it helps remove bias in how a process is viewed, she said.

“I would encourage you to do this on every QI project that you do where you are trying to accomplish something, because it makes a huge difference in understanding the work,” she said.

Stakeholder analysis – understanding the key people whose support could determine the success of the project – is also critical, she said. This can help get buy-in for the change, and it make a project stronger – and without it, you could doom your project, Dr. Tess said.

Doing this well involves understanding their financial and emotional interests, all the way down to whether they prefer face-to-face communication or e-mail, she said.

Then there’s the data. For it to matter, it must be presented well, and that requires context, Dr. Tad-y said.

“Data are just raw facts and figures,” she said. “Data are not the same as information.”

She suggested using run charts, in which data are plotted in some kind of order, usually chronological order. This kind of chart will typically include a median line, showing practice patterns before the QI project began, as well as a “goal line” to aim for, and notations on the timeline when changes were made, she said.

Others will be looking to the project manager for the meaning behind the data, she said.

“The story is going to come from you,” she said. “Otherwise, it’s just numbers.”

Anjala Tess, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, asked the audience how many of them had done a quality improvement project that had failed. It was not a time to be bashful: Almost half the hospitalists in the room admitted that it had happened to them.

Dr. Tess and Darlene Tad-y, MD, chair of the Physicians-in-Training Committee and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, were there to offer help in their session, “Adding to Your QI Toolbox.”

They highlighted three tools that they say are crucial to a project’s success: Creating a process map for clearly outlining how the project will work, interacting with stakeholders productively, and displaying data in a meaningful way.

Process mapping is a way of visualizing work or a process as distinct, ordered, and related steps, Dr. Tess said. Arranged on Post-It notes or written on a white board, the process should be one that can easily be updated. Seen objectively as a set of steps, it helps remove bias in how a process is viewed, she said.

“I would encourage you to do this on every QI project that you do where you are trying to accomplish something, because it makes a huge difference in understanding the work,” she said.

Stakeholder analysis – understanding the key people whose support could determine the success of the project – is also critical, she said. This can help get buy-in for the change, and it make a project stronger – and without it, you could doom your project, Dr. Tess said.

Doing this well involves understanding their financial and emotional interests, all the way down to whether they prefer face-to-face communication or e-mail, she said.

Then there’s the data. For it to matter, it must be presented well, and that requires context, Dr. Tad-y said.

“Data are just raw facts and figures,” she said. “Data are not the same as information.”

She suggested using run charts, in which data are plotted in some kind of order, usually chronological order. This kind of chart will typically include a median line, showing practice patterns before the QI project began, as well as a “goal line” to aim for, and notations on the timeline when changes were made, she said.

Others will be looking to the project manager for the meaning behind the data, she said.

“The story is going to come from you,” she said. “Otherwise, it’s just numbers.”

Work-life balance is not a ‘thing’ but alignment is

We are destined to fail at achieving work-life balance because it does not exist, nor has it ever existed, according to an expert on how people experience time.

The field of chronemics studies the space between people, namely how they communicate with others and with themselves as they experience life in a matrix, not just linearly.

“When we talk about time, we need to remember that context and communication really matter,” Dawna Ballard, PhD, a chronemics expert and associate professor of communication at the University of Texas at Austin, said during a session Tuesday. “We think of our concept of time as ‘truth,’ but when we experience other cultures, often we see they don’t function according to our idea of time.”

The modern concept of time as told by a clock was invented during the Industrial Age to control people and events by forcing a direct line between their lives outside the factory and the farm, according to Dr. Ballard. That is not to say that industrial time is bad. It is efficient and perhaps even necessary for organizing large groups of people, she said.

Time management as a concept evolved out of the ethos of “punching the clock” at the factory, but has carried over to the office where in fact, according to Dr. Ballard, people do not tend to be as effective if they are expected to work in a linear way, since that is not the experience in today’s digital world where interruptions are common. In a survey of 1,000 people, after researchers subtracted the time people spend on email, social media, and other digital interruptions, only 3½ hours of the typical 8-hour work day were left for actual work, and these remaining hours were not consecutive, Dr. Ballard noted.

“In reality, we operate in relationship to time more like we did in preindustrial times than we did during industrial times,” said Dr. Ballard. “Medicine has always had that approach, but the management of it is by people who are still being trained according to industrial [notions] of time.”

The resulting cognitive dissonance contributes to people experiencing guilt for not “balancing” their day properly, according to Dr. Ballard. Because to balance something means separating the pieces and quantifying them separately, people whose lives interrupt them throughout the work day find themselves thinking they have “failed” at achieving a work/life balance, when what they really have done is experience their life as it actually is. “No one likes to feel like a failure, particularly people who are high achievers and who expect to have agency over their lives.”

Dr. Ballard said that an alternative to seeing work and life as components that must be balanced is to instead view these things as being in an alignment that can shift over time. She also suggested challenging the accepted notions of what being productive really means in the context of how one’s life actually is, and to occasionally put down the smartphone and consciously practice experiencing time in an unstructured way.

We are destined to fail at achieving work-life balance because it does not exist, nor has it ever existed, according to an expert on how people experience time.

The field of chronemics studies the space between people, namely how they communicate with others and with themselves as they experience life in a matrix, not just linearly.

“When we talk about time, we need to remember that context and communication really matter,” Dawna Ballard, PhD, a chronemics expert and associate professor of communication at the University of Texas at Austin, said during a session Tuesday. “We think of our concept of time as ‘truth,’ but when we experience other cultures, often we see they don’t function according to our idea of time.”

The modern concept of time as told by a clock was invented during the Industrial Age to control people and events by forcing a direct line between their lives outside the factory and the farm, according to Dr. Ballard. That is not to say that industrial time is bad. It is efficient and perhaps even necessary for organizing large groups of people, she said.

Time management as a concept evolved out of the ethos of “punching the clock” at the factory, but has carried over to the office where in fact, according to Dr. Ballard, people do not tend to be as effective if they are expected to work in a linear way, since that is not the experience in today’s digital world where interruptions are common. In a survey of 1,000 people, after researchers subtracted the time people spend on email, social media, and other digital interruptions, only 3½ hours of the typical 8-hour work day were left for actual work, and these remaining hours were not consecutive, Dr. Ballard noted.

“In reality, we operate in relationship to time more like we did in preindustrial times than we did during industrial times,” said Dr. Ballard. “Medicine has always had that approach, but the management of it is by people who are still being trained according to industrial [notions] of time.”

The resulting cognitive dissonance contributes to people experiencing guilt for not “balancing” their day properly, according to Dr. Ballard. Because to balance something means separating the pieces and quantifying them separately, people whose lives interrupt them throughout the work day find themselves thinking they have “failed” at achieving a work/life balance, when what they really have done is experience their life as it actually is. “No one likes to feel like a failure, particularly people who are high achievers and who expect to have agency over their lives.”

Dr. Ballard said that an alternative to seeing work and life as components that must be balanced is to instead view these things as being in an alignment that can shift over time. She also suggested challenging the accepted notions of what being productive really means in the context of how one’s life actually is, and to occasionally put down the smartphone and consciously practice experiencing time in an unstructured way.

We are destined to fail at achieving work-life balance because it does not exist, nor has it ever existed, according to an expert on how people experience time.

The field of chronemics studies the space between people, namely how they communicate with others and with themselves as they experience life in a matrix, not just linearly.

“When we talk about time, we need to remember that context and communication really matter,” Dawna Ballard, PhD, a chronemics expert and associate professor of communication at the University of Texas at Austin, said during a session Tuesday. “We think of our concept of time as ‘truth,’ but when we experience other cultures, often we see they don’t function according to our idea of time.”

The modern concept of time as told by a clock was invented during the Industrial Age to control people and events by forcing a direct line between their lives outside the factory and the farm, according to Dr. Ballard. That is not to say that industrial time is bad. It is efficient and perhaps even necessary for organizing large groups of people, she said.

Time management as a concept evolved out of the ethos of “punching the clock” at the factory, but has carried over to the office where in fact, according to Dr. Ballard, people do not tend to be as effective if they are expected to work in a linear way, since that is not the experience in today’s digital world where interruptions are common. In a survey of 1,000 people, after researchers subtracted the time people spend on email, social media, and other digital interruptions, only 3½ hours of the typical 8-hour work day were left for actual work, and these remaining hours were not consecutive, Dr. Ballard noted.

“In reality, we operate in relationship to time more like we did in preindustrial times than we did during industrial times,” said Dr. Ballard. “Medicine has always had that approach, but the management of it is by people who are still being trained according to industrial [notions] of time.”

The resulting cognitive dissonance contributes to people experiencing guilt for not “balancing” their day properly, according to Dr. Ballard. Because to balance something means separating the pieces and quantifying them separately, people whose lives interrupt them throughout the work day find themselves thinking they have “failed” at achieving a work/life balance, when what they really have done is experience their life as it actually is. “No one likes to feel like a failure, particularly people who are high achievers and who expect to have agency over their lives.”

Dr. Ballard said that an alternative to seeing work and life as components that must be balanced is to instead view these things as being in an alignment that can shift over time. She also suggested challenging the accepted notions of what being productive really means in the context of how one’s life actually is, and to occasionally put down the smartphone and consciously practice experiencing time in an unstructured way.

VIDEO: SHM seeks sites to test pediatric transition tool

Would you like to help the Society of Hospital Medicine translate its award-winning Project BOOST® Mentored Implementation Program into the pediatric setting?

“We’re hoping to get six sites to help us implement this project so we can collect data and see how well it works for pediatrics,” James O’Callaghan, MD, medical director, EvergreenHealth, Seattle Children’s, said in an interview.

In this video, recorded during HM17 , Dr. O’Callaghan describes how Pedi-BOOST is intended to work, and what types of pediatric transition concerns it is intended to address.

For more information, please visit the SHM website.

Dr. O’Callaghan had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Would you like to help the Society of Hospital Medicine translate its award-winning Project BOOST® Mentored Implementation Program into the pediatric setting?

“We’re hoping to get six sites to help us implement this project so we can collect data and see how well it works for pediatrics,” James O’Callaghan, MD, medical director, EvergreenHealth, Seattle Children’s, said in an interview.

In this video, recorded during HM17 , Dr. O’Callaghan describes how Pedi-BOOST is intended to work, and what types of pediatric transition concerns it is intended to address.

For more information, please visit the SHM website.

Dr. O’Callaghan had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Would you like to help the Society of Hospital Medicine translate its award-winning Project BOOST® Mentored Implementation Program into the pediatric setting?

“We’re hoping to get six sites to help us implement this project so we can collect data and see how well it works for pediatrics,” James O’Callaghan, MD, medical director, EvergreenHealth, Seattle Children’s, said in an interview.

In this video, recorded during HM17 , Dr. O’Callaghan describes how Pedi-BOOST is intended to work, and what types of pediatric transition concerns it is intended to address.

For more information, please visit the SHM website.

Dr. O’Callaghan had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Workshop to help hospitalists with patient flow

The “flow” of patients through the hospital can sometimes resemble a 10-lane expressway at gridlock, said Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor of internal medicine and associate medical director of quality and safety at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle. That is, there’s no flow at all.

Thursday at HM17, Dr. Kim and a panel of experts will lead small workshops of audience members on how to put the “go” back in the flow. The session, “Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput,” will begin at 10 a.m.

“As hospitalists, we are at the sharp end of this problem and are often asked to be key members of project teams assembled to tackle this challenge of patient flow and capacity management,” said Dr. Kim. “We look forward to an interactive session with our audience members.”

The session will address expedited discharge, the idea of the “hospitalist quarterback,” a kind of in-house controller of patient flow; facilitators of transferring to and from outside hospitals; focused efforts on reducing length of stay; establishing short-stay units to enhance patient flow; and participating in continuous process improvement teams, Dr. Kim said.

There will be several small group workshops interspersed with presentations of background content by the workshop facilitators, who represent a wide range of geographic and care settings. Dr. Kim said they have “all experienced the challenges of patient flow and throughput at their hospitals and health systems and have taken leadership roles to address these issues at their medical centers.”

“We anticipate a highly engaging session, where audience members will be divided into different teams, and each team will be tasked to identify specific interventions and challenges in managing the patient flow and capacity management initiative,” said Dr. Berger, associate medical director for inpatient capacity at the University of Washington. “Audience members will work within their own teams, guided by the workshop facilitators, and after the teams come up with their ideas on each of the topics covered in this workshop, each team will have the opportunity to present their best ideas for sharing and feedback.”

The session comes at a time when hospitals are tapping into hospitalists’ experience.

“Many hospitals across the country are challenged with high-occupancy states, creating pressures and external challenges to serve patients’ needs,” said Dr. Parekh, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan. “Hospitalists in their daily work have great familiarity with how hospitals run and where the ‘bottlenecks’ are that [block] patient throughput in their organization. Recognizing this experience and talent for enabling patient flow, many hospitals have turned to hospitalists – and in some cases, resident trainees – to lead or contribute to the hospital’s initiatives to enhance patient throughput.”

The importance of patient flow goes beyond efficiency, Dr. Kim said. Hospital staff who work during high-occupancy days feel the brunt of the burden, and this can lead to patient safety problems.

“We will address the importance of optimal communication between providers and staff, both within hospitals and with outside hospitals to ensure patient safety and staff concerns are appropriately addressed,” he said. “This is a topic that affects everyone at the medical center, and so we believe that this topic is applicable to a broad audience. We hope the participants will be able to facilitate a dialogue with a diverse group of leaders at their hospitals.”

Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput

Thursday, 10:00–11:30 a.m.

The “flow” of patients through the hospital can sometimes resemble a 10-lane expressway at gridlock, said Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor of internal medicine and associate medical director of quality and safety at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle. That is, there’s no flow at all.

Thursday at HM17, Dr. Kim and a panel of experts will lead small workshops of audience members on how to put the “go” back in the flow. The session, “Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput,” will begin at 10 a.m.

“As hospitalists, we are at the sharp end of this problem and are often asked to be key members of project teams assembled to tackle this challenge of patient flow and capacity management,” said Dr. Kim. “We look forward to an interactive session with our audience members.”

The session will address expedited discharge, the idea of the “hospitalist quarterback,” a kind of in-house controller of patient flow; facilitators of transferring to and from outside hospitals; focused efforts on reducing length of stay; establishing short-stay units to enhance patient flow; and participating in continuous process improvement teams, Dr. Kim said.

There will be several small group workshops interspersed with presentations of background content by the workshop facilitators, who represent a wide range of geographic and care settings. Dr. Kim said they have “all experienced the challenges of patient flow and throughput at their hospitals and health systems and have taken leadership roles to address these issues at their medical centers.”

“We anticipate a highly engaging session, where audience members will be divided into different teams, and each team will be tasked to identify specific interventions and challenges in managing the patient flow and capacity management initiative,” said Dr. Berger, associate medical director for inpatient capacity at the University of Washington. “Audience members will work within their own teams, guided by the workshop facilitators, and after the teams come up with their ideas on each of the topics covered in this workshop, each team will have the opportunity to present their best ideas for sharing and feedback.”

The session comes at a time when hospitals are tapping into hospitalists’ experience.

“Many hospitals across the country are challenged with high-occupancy states, creating pressures and external challenges to serve patients’ needs,” said Dr. Parekh, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan. “Hospitalists in their daily work have great familiarity with how hospitals run and where the ‘bottlenecks’ are that [block] patient throughput in their organization. Recognizing this experience and talent for enabling patient flow, many hospitals have turned to hospitalists – and in some cases, resident trainees – to lead or contribute to the hospital’s initiatives to enhance patient throughput.”

The importance of patient flow goes beyond efficiency, Dr. Kim said. Hospital staff who work during high-occupancy days feel the brunt of the burden, and this can lead to patient safety problems.

“We will address the importance of optimal communication between providers and staff, both within hospitals and with outside hospitals to ensure patient safety and staff concerns are appropriately addressed,” he said. “This is a topic that affects everyone at the medical center, and so we believe that this topic is applicable to a broad audience. We hope the participants will be able to facilitate a dialogue with a diverse group of leaders at their hospitals.”

Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput

Thursday, 10:00–11:30 a.m.

The “flow” of patients through the hospital can sometimes resemble a 10-lane expressway at gridlock, said Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate professor of internal medicine and associate medical director of quality and safety at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle. That is, there’s no flow at all.

Thursday at HM17, Dr. Kim and a panel of experts will lead small workshops of audience members on how to put the “go” back in the flow. The session, “Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput,” will begin at 10 a.m.

“As hospitalists, we are at the sharp end of this problem and are often asked to be key members of project teams assembled to tackle this challenge of patient flow and capacity management,” said Dr. Kim. “We look forward to an interactive session with our audience members.”

The session will address expedited discharge, the idea of the “hospitalist quarterback,” a kind of in-house controller of patient flow; facilitators of transferring to and from outside hospitals; focused efforts on reducing length of stay; establishing short-stay units to enhance patient flow; and participating in continuous process improvement teams, Dr. Kim said.

There will be several small group workshops interspersed with presentations of background content by the workshop facilitators, who represent a wide range of geographic and care settings. Dr. Kim said they have “all experienced the challenges of patient flow and throughput at their hospitals and health systems and have taken leadership roles to address these issues at their medical centers.”

“We anticipate a highly engaging session, where audience members will be divided into different teams, and each team will be tasked to identify specific interventions and challenges in managing the patient flow and capacity management initiative,” said Dr. Berger, associate medical director for inpatient capacity at the University of Washington. “Audience members will work within their own teams, guided by the workshop facilitators, and after the teams come up with their ideas on each of the topics covered in this workshop, each team will have the opportunity to present their best ideas for sharing and feedback.”

The session comes at a time when hospitals are tapping into hospitalists’ experience.

“Many hospitals across the country are challenged with high-occupancy states, creating pressures and external challenges to serve patients’ needs,” said Dr. Parekh, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan. “Hospitalists in their daily work have great familiarity with how hospitals run and where the ‘bottlenecks’ are that [block] patient throughput in their organization. Recognizing this experience and talent for enabling patient flow, many hospitals have turned to hospitalists – and in some cases, resident trainees – to lead or contribute to the hospital’s initiatives to enhance patient throughput.”

The importance of patient flow goes beyond efficiency, Dr. Kim said. Hospital staff who work during high-occupancy days feel the brunt of the burden, and this can lead to patient safety problems.

“We will address the importance of optimal communication between providers and staff, both within hospitals and with outside hospitals to ensure patient safety and staff concerns are appropriately addressed,” he said. “This is a topic that affects everyone at the medical center, and so we believe that this topic is applicable to a broad audience. We hope the participants will be able to facilitate a dialogue with a diverse group of leaders at their hospitals.”

Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput

Thursday, 10:00–11:30 a.m.

Systems engineering in the hospital

Systems-engineering expert James Benneyan, PhD, doesn’t want hospitalists to look at poorly working processes in their institutions and think, “I should try to tweak this process to improve it.”

Instead, he wants them to walk out of his HM17 session at 8 a.m. Thursday – appropriately titled, “Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?” – thinking like engineers, which means designing a solution, analyzing how well that process works, and then optimizing it for improvements. If that means not just tweaking a process, but redesigning it from scratch, so be it.

“Systems engineering studies the performance and how to improve the performance of complex systems, particularly sociotechnical systems,” said Dr. Benneyan, who runs the Healthcare Systems Engineering Institute at Northeastern University in Boston, which encompasses four research centers. “Health care is a perfect example … systems engineering can really help to understand and improve complex processes, whether it’s patient flow, safety, on-time discharge [or] better discharge.”

Dr. Benneyan says that systems engineering is, first and foremost, a mindset. It’s an approach to problem solving that’s different, if related, to quality improvement. Both have tremendous value, but they are based on different philosophies, tools, and work styles.

For example, many hospital operating rooms measure how many days the first procedure of the day begins on time. But instead of using that as a yardstick for quality, Dr. Benneyan said a better approach would be designing a system that can adapt to situations when the first case starts late. He compared the process to a delayed flight at an airport. An airline doesn’t back up every plane’s departure when one plane is running behind. Instead, it has systems that adapt to circumstances.

“There are methods and then there are philosophies,” Dr. Benneyan said. “I don’t think people in health care realize what my field did in the airline industry. We didn’t design things that worked and clicked properly. We designed things that … react to daily events and [everything] going on and perform pretty well.”

Dr. Benneyan says that, while health care is an incredibly complex system, other fields with similar levels of technical expertise have used systems engineering much more effectively. Manufacturing, logistics, and global distribution networks are all precise industries requiring hundreds of individual processes to ensure success.

“These are really complicated processes,” he said. “The real barrier is a cultural barrier. Health care is not the most challenging environment to work in. … I think something that people in health care have to have an appreciation for is that the process of doing this work is different from doing their other work. Systems engineering is not the same as quality improvement and can achieve fundamental breakthroughs in cases where QI has not – but also tends to take more work.”

Still, Dr. Benneyan believes his field has lessons that complement quality initiatives. To wit, health care advocates – including the Institute of Medicine, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation – have all pushed for greater application of systems engineering in medicine with the goal of improving how well health care does its job.

While he hopes hospitalists and other HM17 attendees at his session walk away with a newfound respect for and understanding of what systems engineering can do, he doesn’t want them to think it’s too easy.

“There’s a lack of appreciation of the process of engineering and how it’s different,” he said. “It’s a big challenge, partnering clinician with engineers. … We think differently even though we’re both scientifically trained.

“I hope hospitalists take away an appreciation for how this toolkit can be useful in their world.”

Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?

Thursday, 8:00–9:30 a.m.

Systems-engineering expert James Benneyan, PhD, doesn’t want hospitalists to look at poorly working processes in their institutions and think, “I should try to tweak this process to improve it.”

Instead, he wants them to walk out of his HM17 session at 8 a.m. Thursday – appropriately titled, “Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?” – thinking like engineers, which means designing a solution, analyzing how well that process works, and then optimizing it for improvements. If that means not just tweaking a process, but redesigning it from scratch, so be it.

“Systems engineering studies the performance and how to improve the performance of complex systems, particularly sociotechnical systems,” said Dr. Benneyan, who runs the Healthcare Systems Engineering Institute at Northeastern University in Boston, which encompasses four research centers. “Health care is a perfect example … systems engineering can really help to understand and improve complex processes, whether it’s patient flow, safety, on-time discharge [or] better discharge.”

Dr. Benneyan says that systems engineering is, first and foremost, a mindset. It’s an approach to problem solving that’s different, if related, to quality improvement. Both have tremendous value, but they are based on different philosophies, tools, and work styles.

For example, many hospital operating rooms measure how many days the first procedure of the day begins on time. But instead of using that as a yardstick for quality, Dr. Benneyan said a better approach would be designing a system that can adapt to situations when the first case starts late. He compared the process to a delayed flight at an airport. An airline doesn’t back up every plane’s departure when one plane is running behind. Instead, it has systems that adapt to circumstances.

“There are methods and then there are philosophies,” Dr. Benneyan said. “I don’t think people in health care realize what my field did in the airline industry. We didn’t design things that worked and clicked properly. We designed things that … react to daily events and [everything] going on and perform pretty well.”

Dr. Benneyan says that, while health care is an incredibly complex system, other fields with similar levels of technical expertise have used systems engineering much more effectively. Manufacturing, logistics, and global distribution networks are all precise industries requiring hundreds of individual processes to ensure success.

“These are really complicated processes,” he said. “The real barrier is a cultural barrier. Health care is not the most challenging environment to work in. … I think something that people in health care have to have an appreciation for is that the process of doing this work is different from doing their other work. Systems engineering is not the same as quality improvement and can achieve fundamental breakthroughs in cases where QI has not – but also tends to take more work.”

Still, Dr. Benneyan believes his field has lessons that complement quality initiatives. To wit, health care advocates – including the Institute of Medicine, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation – have all pushed for greater application of systems engineering in medicine with the goal of improving how well health care does its job.

While he hopes hospitalists and other HM17 attendees at his session walk away with a newfound respect for and understanding of what systems engineering can do, he doesn’t want them to think it’s too easy.

“There’s a lack of appreciation of the process of engineering and how it’s different,” he said. “It’s a big challenge, partnering clinician with engineers. … We think differently even though we’re both scientifically trained.

“I hope hospitalists take away an appreciation for how this toolkit can be useful in their world.”

Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?

Thursday, 8:00–9:30 a.m.

Systems-engineering expert James Benneyan, PhD, doesn’t want hospitalists to look at poorly working processes in their institutions and think, “I should try to tweak this process to improve it.”

Instead, he wants them to walk out of his HM17 session at 8 a.m. Thursday – appropriately titled, “Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?” – thinking like engineers, which means designing a solution, analyzing how well that process works, and then optimizing it for improvements. If that means not just tweaking a process, but redesigning it from scratch, so be it.

“Systems engineering studies the performance and how to improve the performance of complex systems, particularly sociotechnical systems,” said Dr. Benneyan, who runs the Healthcare Systems Engineering Institute at Northeastern University in Boston, which encompasses four research centers. “Health care is a perfect example … systems engineering can really help to understand and improve complex processes, whether it’s patient flow, safety, on-time discharge [or] better discharge.”

Dr. Benneyan says that systems engineering is, first and foremost, a mindset. It’s an approach to problem solving that’s different, if related, to quality improvement. Both have tremendous value, but they are based on different philosophies, tools, and work styles.

For example, many hospital operating rooms measure how many days the first procedure of the day begins on time. But instead of using that as a yardstick for quality, Dr. Benneyan said a better approach would be designing a system that can adapt to situations when the first case starts late. He compared the process to a delayed flight at an airport. An airline doesn’t back up every plane’s departure when one plane is running behind. Instead, it has systems that adapt to circumstances.

“There are methods and then there are philosophies,” Dr. Benneyan said. “I don’t think people in health care realize what my field did in the airline industry. We didn’t design things that worked and clicked properly. We designed things that … react to daily events and [everything] going on and perform pretty well.”

Dr. Benneyan says that, while health care is an incredibly complex system, other fields with similar levels of technical expertise have used systems engineering much more effectively. Manufacturing, logistics, and global distribution networks are all precise industries requiring hundreds of individual processes to ensure success.

“These are really complicated processes,” he said. “The real barrier is a cultural barrier. Health care is not the most challenging environment to work in. … I think something that people in health care have to have an appreciation for is that the process of doing this work is different from doing their other work. Systems engineering is not the same as quality improvement and can achieve fundamental breakthroughs in cases where QI has not – but also tends to take more work.”

Still, Dr. Benneyan believes his field has lessons that complement quality initiatives. To wit, health care advocates – including the Institute of Medicine, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation – have all pushed for greater application of systems engineering in medicine with the goal of improving how well health care does its job.

While he hopes hospitalists and other HM17 attendees at his session walk away with a newfound respect for and understanding of what systems engineering can do, he doesn’t want them to think it’s too easy.

“There’s a lack of appreciation of the process of engineering and how it’s different,” he said. “It’s a big challenge, partnering clinician with engineers. … We think differently even though we’re both scientifically trained.

“I hope hospitalists take away an appreciation for how this toolkit can be useful in their world.”

Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?

Thursday, 8:00–9:30 a.m.

Diabetes specialist to offer disease management tips

Diabetes is a persistent presence in the hospital, and hospitalists must remain up to date on the latest in disease management.

An endocrinologist will walk the audience through four major points on caring for diabetes patients in a talk to be given Thursday at HM17. The session, “Inpatient Diabetes Management for the Hospitalist,” will begin at 7:40 a.m.

Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FACP, FACE, professor of medicine, director of the clinical research center and section of diabetes and metabolism at Emory University, Atlanta, and section head of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Health System, also in Atlanta, said that, “in most patients, diabetes is a comorbidity that has a serious impact on the outcome of patients with cardiovascular disease or malignancies or surgery.

“Hyperglycemia in patients with or without diabetes can be 30%-40%,” he said. “There are somewhere around 8 to 10 million hospital discharges with diabetes every year in the United States.”

Dr. Umpierrez intends to discuss the following topics in his presentation:

• Intensive insulin therapy. “There is no evidence that intensive insulin therapy aiming to normalize blood glucose [leads to] improvement in outcome and could even [worsen] outcome because of the risk of hypoglycemia. This is true for patients in intensive care and the regular floor.”

• Treatment other than insulin. Guidelines say that using insulin is the only way to manage diabetic patients in the hospital, but evidence is growing that this might not be ideal in some cases, he said.

“Recent evidence in the past 5 years has shown that maybe a one-size-fits-all approach is wrong because using insulin, especially the basal-bolus insulin regimen” – with long-lasting insulin between meals and bolus insulin at mealtime – “can be an overtreatment for some patients with multiple complications and patients with mild hyperglycemia.” In many patients, the administration of a single basal insulin dose (glargine or detemir) is sufficient to achieve reasonable glucose control. In addition, patients with blood glucose less than 180 to 200 mg/dL could benefit from the use of incretin therapy with or without insulin to “at least minimize the risk of hypoglycemia.”

• Limitations for sliding-scale insulin therapy. This approach, in which mealtime bolus insulin is based on blood-sugar level before meals and which has dominated diabetes management over the past 80 years, can bring problems, according to the latest literature, Dr. Umpierrez said.

“Now we have excessive evidence, both in the ICU and non-ICU, that the use of sliding-scale insulin therapy … is associated with higher blood glucose levels [and a] higher rate of complications compared to the use of basal insulin. So, I think that physicians are becoming more aware that sliding scale is not the only way to manage patients in the hospital.”

• Insulin at discharge. The belief that all patients need to go home with insulin might be misguided, he said. “This could be an overtreatment associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia with no benefit in outcome.”

• The use of computer-guided algorithms on insulin therapy. “Are they better than the standard insulin drip protocols that we have? Not clear,” he said. Many commercial versions and institution-generated versions have been developed, but there is uncertainty about their value, he added.

“They may reduce the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Umpierrez said. “We don’t have any evidence that they are better in reducing complications in the hospital. And they can be costly. So the physician has to be aware of the cost. But, it’s an option for some institutions that have very little support from hospitalists or intensivists in their hospital to adjust insulin therapy in the rapidly changing environment in critically ill patients in the ICU.”

Inpatient Diabetes Management for the Hospitalist

Thursday, 7:40–8:15 a.m.

Diabetes is a persistent presence in the hospital, and hospitalists must remain up to date on the latest in disease management.

An endocrinologist will walk the audience through four major points on caring for diabetes patients in a talk to be given Thursday at HM17. The session, “Inpatient Diabetes Management for the Hospitalist,” will begin at 7:40 a.m.

Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FACP, FACE, professor of medicine, director of the clinical research center and section of diabetes and metabolism at Emory University, Atlanta, and section head of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Health System, also in Atlanta, said that, “in most patients, diabetes is a comorbidity that has a serious impact on the outcome of patients with cardiovascular disease or malignancies or surgery.

“Hyperglycemia in patients with or without diabetes can be 30%-40%,” he said. “There are somewhere around 8 to 10 million hospital discharges with diabetes every year in the United States.”

Dr. Umpierrez intends to discuss the following topics in his presentation:

• Intensive insulin therapy. “There is no evidence that intensive insulin therapy aiming to normalize blood glucose [leads to] improvement in outcome and could even [worsen] outcome because of the risk of hypoglycemia. This is true for patients in intensive care and the regular floor.”

• Treatment other than insulin. Guidelines say that using insulin is the only way to manage diabetic patients in the hospital, but evidence is growing that this might not be ideal in some cases, he said.

“Recent evidence in the past 5 years has shown that maybe a one-size-fits-all approach is wrong because using insulin, especially the basal-bolus insulin regimen” – with long-lasting insulin between meals and bolus insulin at mealtime – “can be an overtreatment for some patients with multiple complications and patients with mild hyperglycemia.” In many patients, the administration of a single basal insulin dose (glargine or detemir) is sufficient to achieve reasonable glucose control. In addition, patients with blood glucose less than 180 to 200 mg/dL could benefit from the use of incretin therapy with or without insulin to “at least minimize the risk of hypoglycemia.”

• Limitations for sliding-scale insulin therapy. This approach, in which mealtime bolus insulin is based on blood-sugar level before meals and which has dominated diabetes management over the past 80 years, can bring problems, according to the latest literature, Dr. Umpierrez said.

“Now we have excessive evidence, both in the ICU and non-ICU, that the use of sliding-scale insulin therapy … is associated with higher blood glucose levels [and a] higher rate of complications compared to the use of basal insulin. So, I think that physicians are becoming more aware that sliding scale is not the only way to manage patients in the hospital.”

• Insulin at discharge. The belief that all patients need to go home with insulin might be misguided, he said. “This could be an overtreatment associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia with no benefit in outcome.”

• The use of computer-guided algorithms on insulin therapy. “Are they better than the standard insulin drip protocols that we have? Not clear,” he said. Many commercial versions and institution-generated versions have been developed, but there is uncertainty about their value, he added.

“They may reduce the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Umpierrez said. “We don’t have any evidence that they are better in reducing complications in the hospital. And they can be costly. So the physician has to be aware of the cost. But, it’s an option for some institutions that have very little support from hospitalists or intensivists in their hospital to adjust insulin therapy in the rapidly changing environment in critically ill patients in the ICU.”

Inpatient Diabetes Management for the Hospitalist

Thursday, 7:40–8:15 a.m.

Diabetes is a persistent presence in the hospital, and hospitalists must remain up to date on the latest in disease management.

An endocrinologist will walk the audience through four major points on caring for diabetes patients in a talk to be given Thursday at HM17. The session, “Inpatient Diabetes Management for the Hospitalist,” will begin at 7:40 a.m.

Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FACP, FACE, professor of medicine, director of the clinical research center and section of diabetes and metabolism at Emory University, Atlanta, and section head of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Health System, also in Atlanta, said that, “in most patients, diabetes is a comorbidity that has a serious impact on the outcome of patients with cardiovascular disease or malignancies or surgery.

“Hyperglycemia in patients with or without diabetes can be 30%-40%,” he said. “There are somewhere around 8 to 10 million hospital discharges with diabetes every year in the United States.”

Dr. Umpierrez intends to discuss the following topics in his presentation:

• Intensive insulin therapy. “There is no evidence that intensive insulin therapy aiming to normalize blood glucose [leads to] improvement in outcome and could even [worsen] outcome because of the risk of hypoglycemia. This is true for patients in intensive care and the regular floor.”

• Treatment other than insulin. Guidelines say that using insulin is the only way to manage diabetic patients in the hospital, but evidence is growing that this might not be ideal in some cases, he said.

“Recent evidence in the past 5 years has shown that maybe a one-size-fits-all approach is wrong because using insulin, especially the basal-bolus insulin regimen” – with long-lasting insulin between meals and bolus insulin at mealtime – “can be an overtreatment for some patients with multiple complications and patients with mild hyperglycemia.” In many patients, the administration of a single basal insulin dose (glargine or detemir) is sufficient to achieve reasonable glucose control. In addition, patients with blood glucose less than 180 to 200 mg/dL could benefit from the use of incretin therapy with or without insulin to “at least minimize the risk of hypoglycemia.”

• Limitations for sliding-scale insulin therapy. This approach, in which mealtime bolus insulin is based on blood-sugar level before meals and which has dominated diabetes management over the past 80 years, can bring problems, according to the latest literature, Dr. Umpierrez said.