User login

Morbidly adherent placenta: A multidisciplinary approach

The rate of placenta accreta has been rising, almost certainly as a consequence of the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is estimated that morbidly adherent placenta (placenta accreta, increta, and percreta) occurs today in approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies. Women who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other uterine surgery, such as myomectomy, are at higher risk.

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is associated with significant hemorrhage and morbidity – not only in cases of attempted placental removal, which is usually not advisable, but also in cases of cesarean hysterectomy. Cesarean hysterectomy is technically complex and completely different from other hysterectomies. The abnormal vasculature of MAP requires intricate, stepwise, vessel-by-vessel dissection and not only the uterine artery ligation that is the focus in hysterectomies performed for other indications.

In the last several years, we have demonstrated improved outcomes with such an approach at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 2014, we instituted a multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program for patients with MAP and others at high risk of intrapartum and postpartum complications. The program brings together obstetric anesthesiologists, the blood bank staff, the neonatal and surgical intensive care unit staff, vascular surgeons, perinatologists, interventional radiologists, urologists, and others.

Since the program was implemented, we have reduced our transfusion rate in patients with MAP by more than 60% while caring for increasing numbers of patients with the condition. We also have reduced the intensive care unit admission rate and improved overall surgical morbidity, including bladder complications. Moreover, our multidisciplinary approach is allowing us to develop more algorithms for management and to selectively take conservative approaches while also allowing us to lay the groundwork for future research.

The patients at risk

Anticipation is important: Identifying patient populations at high risk – and then evaluating individual risks – is essential for the prevention of delivery complications and the reduction of maternal morbidity.

Having had multiple cesarean deliveries – especially in pregnancies involving placenta previa – is one of the most important risk factors for developing MAP. One prospective cohort study of more than 30,000 women in 19 academic centers who had had cesarean deliveries found that, in cases of placenta previa, the risk of placenta accreta went from 3% after one cesarean delivery to 67% after five or more cesarean deliveries (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jun;107[6]:1226-32). Placenta accreta was defined in this study as the placenta’s being adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation. This definition included all forms of MAP.

Even without a history of placenta previa, patients who have had multiple cesarean deliveries – and developed consequent myometrial damage and scarring – should be evaluated for placental location during future pregnancies, as should patients who have had a myomectomy. A placenta that is anteriorly located in a patient who had a prior classical cesarean incision should also be thoroughly investigated. Overall, there is a risk of MAP whenever the placenta attaches to an area of uterine scarring.

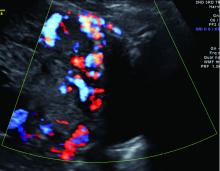

Diagnosis of MAP can be made – as best as is currently possible – by ultrasonography or by MRI, the latter of which is performed in high-risk or ambiguous cases to look more closely at the depth of placental growth.

Our outcomes and process

In our complex obstetric surgery program, we identify and evaluate patients at risk for developing MAP and also prepare comprehensive surgical plans. Each individual’s plan addresses the optimal timing of and conditions for delivery, how the patient and the team should prepare for high-quality perioperative care, and how possible complications and emergency surgery should be handled, such as who should be called in the case of emergency preterm delivery.

Indeed, research has shown that the value of a multidisciplinary approach is greatest when MAP is identified or suspected before delivery. For instance, investigators who analyzed the pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta in Utah over a 12-year period found that cases managed by a multidisciplinary care team had a 50% risk reduction for early morbidities, compared with cases managed with standard obstetric care. The benefits were even greater when placenta accreta (defined in the study to include the spectrum of MAP) was suspected before delivery; this group had a nearly 80% risk reduction with multidisciplinary care (Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117[2 Pt 1]:331-7).

We recently compared our outcomes before and after the multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program was established. For patients with MAP, estimated blood loss has decreased by 40%, and the use of blood products has fallen by 60%-70%, with a corresponding reduction in intensive care unit admission. Moreover, our bladder complication rate fell to 6% after program implementation. This and our reoperation rate, among other outcomes, are lower than published rates from other similar medical centers that use a multidisciplinary approach.

We strive to have two surgeons in the operating room – either two senior surgeons or one senior surgeon and one junior surgeon – as well as a separate “operation supervisor” who monitors blood loss (volume and sources), vital signs, and other clinical points and who is continually thinking about next steps. The operation supervisor is not necessarily a third surgeon but could be an experienced surgical nurse or an obstetric anesthesiologist.

Obstetric anesthesiologists and the blood bank staff have proven to be especially important parts of our multidisciplinary team. At 28-30 weeks’ gestation, each patient has an anesthesia consult and also is tested for blood type and screened for antibodies. Patients also are tested for anemia at this time so that it may be corrected if necessary before surgery.

As determined by our multidisciplinary team, all deliveries are performed under general anesthesia, with early placement of both a central venous catheter and a peripheral arterial line to enable rapid transfusions of blood or fluid. Patients are routinely placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, which enables direct access to the vagina and better assessment of vaginal bleeding. And, when significant blood loss is anticipated, the intensive care unit team prepares a bed, and our surgical colleagues are alerted.

Conservative management

Interest in conservative management – in avoiding hysterectomy when it is deemed to carry much higher risks of hemorrhage or injury to adjacent tissue than leaving the placenta in situ – has resurged in Europe. However, research is still in its infancy regarding the benefits and safety of conservative management, and clear guidance about eligibility and contraindications is still needed (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:755-60).

One patient with the placenta left in situ had an urgent hysterectomy within 2 hours of delivery because of vaginal bleeding, with the total blood loss within an acceptable range and without complications. Another required an urgent hysterectomy 6 weeks after delivery because of severe hemorrhaging. The remaining two had nonurgent hysterectomies at least 6 weeks later, with the total blood loss minimized by the period of recovery and by some spontaneous regression of the placental bulk.

As we have gained more experience with conservative management and spent more time shaping multidisciplinary protocols, it has become clear to us that programs must have in place excellent protocols and strict rules for monitoring and follow-up given the risks of life-threatening hemorrhage and other significant complications when the placenta is left in situ.

A conservative approach also may be preferred by women who desire fertility preservation. Currently, in such cases, we have performed segmental or local resection with uterine repair. We do not yet have any data on subsequent pregnancies.

Research conducted within the growing sphere of complex obstetric surgery should help us to improve decision making and management of MAP. For instance, we need better imaging techniques to more accurately predict MAP and show us the degree of placental invasion. A study published several years ago that blinded sonographers from information about patients’ clinical history and risk factors found significant interobserver variability for the diagnosis of placenta accreta and sensitivity (53.5%) that was significantly lower than previously described (J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33[12]:2153-8).

Dr. Turan’s stepwise dissection

In addition to a multidisciplinary approach, a meticulous dissection technique can help drive improved outcomes. The morbidly adherent placenta is a hypervascular organ; it recruits a host of blood vessels, largely from the vaginal arteries, superior vesical arteries, and vaginal venous plexus.

Moreover, in most cases, this vascular remodeling exacerbates vascular patterns that are distorted to begin with as a result of the scarring process following previous uterine surgery. Scarred tissue is already hypervascular.

I have found that most of the blood loss during hysterectomy occurs during dissection of the poorly defined interface between the lower uterine segment and the bladder and not during dissection of the uterine artery. Identification of the cleavage plane and ligation of each individual vessel using a bipolar or small hand-held desiccation device are key in reducing blood loss. This can take a significant amount of time but is well worth it.

Managing super morbid obesity

The number of pregnant women who require challenging obstetric surgeries is increasing, and this includes women with super morbid obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2 or weight greater than 350 lb). Cesarean deliveries for these patients have proven to be much more complicated, involving special anesthesia needs, for instance.

In addition to women with placental implantation abnormalities (MAP and placenta previa, for instance) and those with extreme morbid obesity, the complex obstetric surgery program also aims to manage patients with increased risk for surgical morbidities based on previous surgery, patients whose fetuses require ex utero intrapartum treatment, and women who require abdominal cerclage.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The rate of placenta accreta has been rising, almost certainly as a consequence of the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is estimated that morbidly adherent placenta (placenta accreta, increta, and percreta) occurs today in approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies. Women who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other uterine surgery, such as myomectomy, are at higher risk.

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is associated with significant hemorrhage and morbidity – not only in cases of attempted placental removal, which is usually not advisable, but also in cases of cesarean hysterectomy. Cesarean hysterectomy is technically complex and completely different from other hysterectomies. The abnormal vasculature of MAP requires intricate, stepwise, vessel-by-vessel dissection and not only the uterine artery ligation that is the focus in hysterectomies performed for other indications.

In the last several years, we have demonstrated improved outcomes with such an approach at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 2014, we instituted a multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program for patients with MAP and others at high risk of intrapartum and postpartum complications. The program brings together obstetric anesthesiologists, the blood bank staff, the neonatal and surgical intensive care unit staff, vascular surgeons, perinatologists, interventional radiologists, urologists, and others.

Since the program was implemented, we have reduced our transfusion rate in patients with MAP by more than 60% while caring for increasing numbers of patients with the condition. We also have reduced the intensive care unit admission rate and improved overall surgical morbidity, including bladder complications. Moreover, our multidisciplinary approach is allowing us to develop more algorithms for management and to selectively take conservative approaches while also allowing us to lay the groundwork for future research.

The patients at risk

Anticipation is important: Identifying patient populations at high risk – and then evaluating individual risks – is essential for the prevention of delivery complications and the reduction of maternal morbidity.

Having had multiple cesarean deliveries – especially in pregnancies involving placenta previa – is one of the most important risk factors for developing MAP. One prospective cohort study of more than 30,000 women in 19 academic centers who had had cesarean deliveries found that, in cases of placenta previa, the risk of placenta accreta went from 3% after one cesarean delivery to 67% after five or more cesarean deliveries (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jun;107[6]:1226-32). Placenta accreta was defined in this study as the placenta’s being adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation. This definition included all forms of MAP.

Even without a history of placenta previa, patients who have had multiple cesarean deliveries – and developed consequent myometrial damage and scarring – should be evaluated for placental location during future pregnancies, as should patients who have had a myomectomy. A placenta that is anteriorly located in a patient who had a prior classical cesarean incision should also be thoroughly investigated. Overall, there is a risk of MAP whenever the placenta attaches to an area of uterine scarring.

Diagnosis of MAP can be made – as best as is currently possible – by ultrasonography or by MRI, the latter of which is performed in high-risk or ambiguous cases to look more closely at the depth of placental growth.

Our outcomes and process

In our complex obstetric surgery program, we identify and evaluate patients at risk for developing MAP and also prepare comprehensive surgical plans. Each individual’s plan addresses the optimal timing of and conditions for delivery, how the patient and the team should prepare for high-quality perioperative care, and how possible complications and emergency surgery should be handled, such as who should be called in the case of emergency preterm delivery.

Indeed, research has shown that the value of a multidisciplinary approach is greatest when MAP is identified or suspected before delivery. For instance, investigators who analyzed the pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta in Utah over a 12-year period found that cases managed by a multidisciplinary care team had a 50% risk reduction for early morbidities, compared with cases managed with standard obstetric care. The benefits were even greater when placenta accreta (defined in the study to include the spectrum of MAP) was suspected before delivery; this group had a nearly 80% risk reduction with multidisciplinary care (Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117[2 Pt 1]:331-7).

We recently compared our outcomes before and after the multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program was established. For patients with MAP, estimated blood loss has decreased by 40%, and the use of blood products has fallen by 60%-70%, with a corresponding reduction in intensive care unit admission. Moreover, our bladder complication rate fell to 6% after program implementation. This and our reoperation rate, among other outcomes, are lower than published rates from other similar medical centers that use a multidisciplinary approach.

We strive to have two surgeons in the operating room – either two senior surgeons or one senior surgeon and one junior surgeon – as well as a separate “operation supervisor” who monitors blood loss (volume and sources), vital signs, and other clinical points and who is continually thinking about next steps. The operation supervisor is not necessarily a third surgeon but could be an experienced surgical nurse or an obstetric anesthesiologist.

Obstetric anesthesiologists and the blood bank staff have proven to be especially important parts of our multidisciplinary team. At 28-30 weeks’ gestation, each patient has an anesthesia consult and also is tested for blood type and screened for antibodies. Patients also are tested for anemia at this time so that it may be corrected if necessary before surgery.

As determined by our multidisciplinary team, all deliveries are performed under general anesthesia, with early placement of both a central venous catheter and a peripheral arterial line to enable rapid transfusions of blood or fluid. Patients are routinely placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, which enables direct access to the vagina and better assessment of vaginal bleeding. And, when significant blood loss is anticipated, the intensive care unit team prepares a bed, and our surgical colleagues are alerted.

Conservative management

Interest in conservative management – in avoiding hysterectomy when it is deemed to carry much higher risks of hemorrhage or injury to adjacent tissue than leaving the placenta in situ – has resurged in Europe. However, research is still in its infancy regarding the benefits and safety of conservative management, and clear guidance about eligibility and contraindications is still needed (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:755-60).

One patient with the placenta left in situ had an urgent hysterectomy within 2 hours of delivery because of vaginal bleeding, with the total blood loss within an acceptable range and without complications. Another required an urgent hysterectomy 6 weeks after delivery because of severe hemorrhaging. The remaining two had nonurgent hysterectomies at least 6 weeks later, with the total blood loss minimized by the period of recovery and by some spontaneous regression of the placental bulk.

As we have gained more experience with conservative management and spent more time shaping multidisciplinary protocols, it has become clear to us that programs must have in place excellent protocols and strict rules for monitoring and follow-up given the risks of life-threatening hemorrhage and other significant complications when the placenta is left in situ.

A conservative approach also may be preferred by women who desire fertility preservation. Currently, in such cases, we have performed segmental or local resection with uterine repair. We do not yet have any data on subsequent pregnancies.

Research conducted within the growing sphere of complex obstetric surgery should help us to improve decision making and management of MAP. For instance, we need better imaging techniques to more accurately predict MAP and show us the degree of placental invasion. A study published several years ago that blinded sonographers from information about patients’ clinical history and risk factors found significant interobserver variability for the diagnosis of placenta accreta and sensitivity (53.5%) that was significantly lower than previously described (J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33[12]:2153-8).

Dr. Turan’s stepwise dissection

In addition to a multidisciplinary approach, a meticulous dissection technique can help drive improved outcomes. The morbidly adherent placenta is a hypervascular organ; it recruits a host of blood vessels, largely from the vaginal arteries, superior vesical arteries, and vaginal venous plexus.

Moreover, in most cases, this vascular remodeling exacerbates vascular patterns that are distorted to begin with as a result of the scarring process following previous uterine surgery. Scarred tissue is already hypervascular.

I have found that most of the blood loss during hysterectomy occurs during dissection of the poorly defined interface between the lower uterine segment and the bladder and not during dissection of the uterine artery. Identification of the cleavage plane and ligation of each individual vessel using a bipolar or small hand-held desiccation device are key in reducing blood loss. This can take a significant amount of time but is well worth it.

Managing super morbid obesity

The number of pregnant women who require challenging obstetric surgeries is increasing, and this includes women with super morbid obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2 or weight greater than 350 lb). Cesarean deliveries for these patients have proven to be much more complicated, involving special anesthesia needs, for instance.

In addition to women with placental implantation abnormalities (MAP and placenta previa, for instance) and those with extreme morbid obesity, the complex obstetric surgery program also aims to manage patients with increased risk for surgical morbidities based on previous surgery, patients whose fetuses require ex utero intrapartum treatment, and women who require abdominal cerclage.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The rate of placenta accreta has been rising, almost certainly as a consequence of the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is estimated that morbidly adherent placenta (placenta accreta, increta, and percreta) occurs today in approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies. Women who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other uterine surgery, such as myomectomy, are at higher risk.

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is associated with significant hemorrhage and morbidity – not only in cases of attempted placental removal, which is usually not advisable, but also in cases of cesarean hysterectomy. Cesarean hysterectomy is technically complex and completely different from other hysterectomies. The abnormal vasculature of MAP requires intricate, stepwise, vessel-by-vessel dissection and not only the uterine artery ligation that is the focus in hysterectomies performed for other indications.

In the last several years, we have demonstrated improved outcomes with such an approach at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 2014, we instituted a multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program for patients with MAP and others at high risk of intrapartum and postpartum complications. The program brings together obstetric anesthesiologists, the blood bank staff, the neonatal and surgical intensive care unit staff, vascular surgeons, perinatologists, interventional radiologists, urologists, and others.

Since the program was implemented, we have reduced our transfusion rate in patients with MAP by more than 60% while caring for increasing numbers of patients with the condition. We also have reduced the intensive care unit admission rate and improved overall surgical morbidity, including bladder complications. Moreover, our multidisciplinary approach is allowing us to develop more algorithms for management and to selectively take conservative approaches while also allowing us to lay the groundwork for future research.

The patients at risk

Anticipation is important: Identifying patient populations at high risk – and then evaluating individual risks – is essential for the prevention of delivery complications and the reduction of maternal morbidity.

Having had multiple cesarean deliveries – especially in pregnancies involving placenta previa – is one of the most important risk factors for developing MAP. One prospective cohort study of more than 30,000 women in 19 academic centers who had had cesarean deliveries found that, in cases of placenta previa, the risk of placenta accreta went from 3% after one cesarean delivery to 67% after five or more cesarean deliveries (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jun;107[6]:1226-32). Placenta accreta was defined in this study as the placenta’s being adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation. This definition included all forms of MAP.

Even without a history of placenta previa, patients who have had multiple cesarean deliveries – and developed consequent myometrial damage and scarring – should be evaluated for placental location during future pregnancies, as should patients who have had a myomectomy. A placenta that is anteriorly located in a patient who had a prior classical cesarean incision should also be thoroughly investigated. Overall, there is a risk of MAP whenever the placenta attaches to an area of uterine scarring.

Diagnosis of MAP can be made – as best as is currently possible – by ultrasonography or by MRI, the latter of which is performed in high-risk or ambiguous cases to look more closely at the depth of placental growth.

Our outcomes and process

In our complex obstetric surgery program, we identify and evaluate patients at risk for developing MAP and also prepare comprehensive surgical plans. Each individual’s plan addresses the optimal timing of and conditions for delivery, how the patient and the team should prepare for high-quality perioperative care, and how possible complications and emergency surgery should be handled, such as who should be called in the case of emergency preterm delivery.

Indeed, research has shown that the value of a multidisciplinary approach is greatest when MAP is identified or suspected before delivery. For instance, investigators who analyzed the pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta in Utah over a 12-year period found that cases managed by a multidisciplinary care team had a 50% risk reduction for early morbidities, compared with cases managed with standard obstetric care. The benefits were even greater when placenta accreta (defined in the study to include the spectrum of MAP) was suspected before delivery; this group had a nearly 80% risk reduction with multidisciplinary care (Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117[2 Pt 1]:331-7).

We recently compared our outcomes before and after the multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program was established. For patients with MAP, estimated blood loss has decreased by 40%, and the use of blood products has fallen by 60%-70%, with a corresponding reduction in intensive care unit admission. Moreover, our bladder complication rate fell to 6% after program implementation. This and our reoperation rate, among other outcomes, are lower than published rates from other similar medical centers that use a multidisciplinary approach.

We strive to have two surgeons in the operating room – either two senior surgeons or one senior surgeon and one junior surgeon – as well as a separate “operation supervisor” who monitors blood loss (volume and sources), vital signs, and other clinical points and who is continually thinking about next steps. The operation supervisor is not necessarily a third surgeon but could be an experienced surgical nurse or an obstetric anesthesiologist.

Obstetric anesthesiologists and the blood bank staff have proven to be especially important parts of our multidisciplinary team. At 28-30 weeks’ gestation, each patient has an anesthesia consult and also is tested for blood type and screened for antibodies. Patients also are tested for anemia at this time so that it may be corrected if necessary before surgery.

As determined by our multidisciplinary team, all deliveries are performed under general anesthesia, with early placement of both a central venous catheter and a peripheral arterial line to enable rapid transfusions of blood or fluid. Patients are routinely placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, which enables direct access to the vagina and better assessment of vaginal bleeding. And, when significant blood loss is anticipated, the intensive care unit team prepares a bed, and our surgical colleagues are alerted.

Conservative management

Interest in conservative management – in avoiding hysterectomy when it is deemed to carry much higher risks of hemorrhage or injury to adjacent tissue than leaving the placenta in situ – has resurged in Europe. However, research is still in its infancy regarding the benefits and safety of conservative management, and clear guidance about eligibility and contraindications is still needed (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:755-60).

One patient with the placenta left in situ had an urgent hysterectomy within 2 hours of delivery because of vaginal bleeding, with the total blood loss within an acceptable range and without complications. Another required an urgent hysterectomy 6 weeks after delivery because of severe hemorrhaging. The remaining two had nonurgent hysterectomies at least 6 weeks later, with the total blood loss minimized by the period of recovery and by some spontaneous regression of the placental bulk.

As we have gained more experience with conservative management and spent more time shaping multidisciplinary protocols, it has become clear to us that programs must have in place excellent protocols and strict rules for monitoring and follow-up given the risks of life-threatening hemorrhage and other significant complications when the placenta is left in situ.

A conservative approach also may be preferred by women who desire fertility preservation. Currently, in such cases, we have performed segmental or local resection with uterine repair. We do not yet have any data on subsequent pregnancies.

Research conducted within the growing sphere of complex obstetric surgery should help us to improve decision making and management of MAP. For instance, we need better imaging techniques to more accurately predict MAP and show us the degree of placental invasion. A study published several years ago that blinded sonographers from information about patients’ clinical history and risk factors found significant interobserver variability for the diagnosis of placenta accreta and sensitivity (53.5%) that was significantly lower than previously described (J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33[12]:2153-8).

Dr. Turan’s stepwise dissection

In addition to a multidisciplinary approach, a meticulous dissection technique can help drive improved outcomes. The morbidly adherent placenta is a hypervascular organ; it recruits a host of blood vessels, largely from the vaginal arteries, superior vesical arteries, and vaginal venous plexus.

Moreover, in most cases, this vascular remodeling exacerbates vascular patterns that are distorted to begin with as a result of the scarring process following previous uterine surgery. Scarred tissue is already hypervascular.

I have found that most of the blood loss during hysterectomy occurs during dissection of the poorly defined interface between the lower uterine segment and the bladder and not during dissection of the uterine artery. Identification of the cleavage plane and ligation of each individual vessel using a bipolar or small hand-held desiccation device are key in reducing blood loss. This can take a significant amount of time but is well worth it.

Managing super morbid obesity

The number of pregnant women who require challenging obstetric surgeries is increasing, and this includes women with super morbid obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2 or weight greater than 350 lb). Cesarean deliveries for these patients have proven to be much more complicated, involving special anesthesia needs, for instance.

In addition to women with placental implantation abnormalities (MAP and placenta previa, for instance) and those with extreme morbid obesity, the complex obstetric surgery program also aims to manage patients with increased risk for surgical morbidities based on previous surgery, patients whose fetuses require ex utero intrapartum treatment, and women who require abdominal cerclage.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Multidisciplinary teams offer key to complex deliveries

Medical practice has evolved, and will continue to do so, as we begin pushing for more personalized and better precision health care. Gone are the days of the general practitioner who attempted to treat all conditions in all patients. Health care is now so complex that not only specialists but also so-called superspecialists are needed to manage complicated cases successfully.

One of the biggest challenges, and greatest opportunities, in ob.gyn. is the need to establish a multidisciplinary health team to the address the needs of today’s patients. More than ever, we are working with patients with advanced maternal age having their first pregnancies. More than ever, we are managing patients who have preexisting diabetes and are concurrently overweight or obese. More than ever, our patients are having multiple cesarean deliveries. More than ever, our patients are hoping – perhaps even expecting – to retain their fertility after a complicated delivery. More than ever, a single patient may need the guidance and care of not just an ob.gyn. or maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist but also an endocrinologist, cardiologist, diabetologist, genetic counselor, nutritionist – the list could go on.

The emergence and continued growth of personalized and preventive medicine in the very near future will catalyze fundamental changes at many different levels in health care and health systems. The need to establish multidisciplinary care teams is already apparent in ob.gyn. but is especially necessary in helping patients who experience complicated deliveries that could jeopardize their immediate and long-term health and fertility.

This month, we have invited M. Ozhan Turan, MD, PhD, the director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to discuss the use of a multidisciplinary team in the management of patients with placenta accreta and other forms of morbidly adherent placenta.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column.

Medical practice has evolved, and will continue to do so, as we begin pushing for more personalized and better precision health care. Gone are the days of the general practitioner who attempted to treat all conditions in all patients. Health care is now so complex that not only specialists but also so-called superspecialists are needed to manage complicated cases successfully.

One of the biggest challenges, and greatest opportunities, in ob.gyn. is the need to establish a multidisciplinary health team to the address the needs of today’s patients. More than ever, we are working with patients with advanced maternal age having their first pregnancies. More than ever, we are managing patients who have preexisting diabetes and are concurrently overweight or obese. More than ever, our patients are having multiple cesarean deliveries. More than ever, our patients are hoping – perhaps even expecting – to retain their fertility after a complicated delivery. More than ever, a single patient may need the guidance and care of not just an ob.gyn. or maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist but also an endocrinologist, cardiologist, diabetologist, genetic counselor, nutritionist – the list could go on.

The emergence and continued growth of personalized and preventive medicine in the very near future will catalyze fundamental changes at many different levels in health care and health systems. The need to establish multidisciplinary care teams is already apparent in ob.gyn. but is especially necessary in helping patients who experience complicated deliveries that could jeopardize their immediate and long-term health and fertility.

This month, we have invited M. Ozhan Turan, MD, PhD, the director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to discuss the use of a multidisciplinary team in the management of patients with placenta accreta and other forms of morbidly adherent placenta.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column.

Medical practice has evolved, and will continue to do so, as we begin pushing for more personalized and better precision health care. Gone are the days of the general practitioner who attempted to treat all conditions in all patients. Health care is now so complex that not only specialists but also so-called superspecialists are needed to manage complicated cases successfully.

One of the biggest challenges, and greatest opportunities, in ob.gyn. is the need to establish a multidisciplinary health team to the address the needs of today’s patients. More than ever, we are working with patients with advanced maternal age having their first pregnancies. More than ever, we are managing patients who have preexisting diabetes and are concurrently overweight or obese. More than ever, our patients are having multiple cesarean deliveries. More than ever, our patients are hoping – perhaps even expecting – to retain their fertility after a complicated delivery. More than ever, a single patient may need the guidance and care of not just an ob.gyn. or maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist but also an endocrinologist, cardiologist, diabetologist, genetic counselor, nutritionist – the list could go on.

The emergence and continued growth of personalized and preventive medicine in the very near future will catalyze fundamental changes at many different levels in health care and health systems. The need to establish multidisciplinary care teams is already apparent in ob.gyn. but is especially necessary in helping patients who experience complicated deliveries that could jeopardize their immediate and long-term health and fertility.

This month, we have invited M. Ozhan Turan, MD, PhD, the director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to discuss the use of a multidisciplinary team in the management of patients with placenta accreta and other forms of morbidly adherent placenta.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column.

A multidisciplinary approach to diaphragmatic endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis

The first case of diaphragmatic endometriosis was reported by Alan Brews in 19541. Unfortunately, no guidelines exist to enhance the recognition and treatment.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis often is overlooked by the gynecologist, not only because of lack of appreciation of the symptoms but also because of the failure to properly work-up the patient and evaluate the diaphragm at time of surgery. In a retrospective review of 3,008 patients with pelvic endometriosis published in Surgical Endoscopy in 2013, Marcello Ceccaroni, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found 46 cases (1.53%) with the intraoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis, six with liver involvement. Multiple diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were seen in 70% of patients and, the vast majority being right-sided lesions (87%), with 11% of cases having bilateral lesions.2 While in the study, superficial lesions were generally vaporized using the argon beam coagulator, deep lesions were removed by sharp dissection, highlighting the need to have adequately trained minimally invasive surgeons treating diaphragmatic lesions via incision. If a pneumothorax occurred, and reabsorbable suture was placed after adequate expansion of the lung via positive pressure ventilation and progressive air suctioning with complete evacuation of the pneumothorax prior to the final closure (i.e., a purse string around the suction device), then the integrity of the closure could be proven using a bubble test with 500cc of saline placed at the diaphragm.

As the gynecologic surgeon studies Dr. Nezhat’s thorough discourse, it is obvious that, at times, a multidisciplinary team must be involved. Although possible, it would appear that risk of diaphragm paralysis secondary to injury of the phrenic nerve is indeed rare. This likely is because of the greater incidence of right-sided disease, rather than involving the central tendon, and lower likelihood that the lesion penetrates deeply. Nevertheless, a prudent multidisciplinary approach and knowledge of the anatomy will inevitably further reduce this rare complication.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He reported having no financial disclosures related to this column.

References

1. Proc R Soc Med. 1954 Jun; 47(6):461-8.

2. Surg Endosc. 2013 Feb;27(2):625-32.

The first case of diaphragmatic endometriosis was reported by Alan Brews in 19541. Unfortunately, no guidelines exist to enhance the recognition and treatment.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis often is overlooked by the gynecologist, not only because of lack of appreciation of the symptoms but also because of the failure to properly work-up the patient and evaluate the diaphragm at time of surgery. In a retrospective review of 3,008 patients with pelvic endometriosis published in Surgical Endoscopy in 2013, Marcello Ceccaroni, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found 46 cases (1.53%) with the intraoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis, six with liver involvement. Multiple diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were seen in 70% of patients and, the vast majority being right-sided lesions (87%), with 11% of cases having bilateral lesions.2 While in the study, superficial lesions were generally vaporized using the argon beam coagulator, deep lesions were removed by sharp dissection, highlighting the need to have adequately trained minimally invasive surgeons treating diaphragmatic lesions via incision. If a pneumothorax occurred, and reabsorbable suture was placed after adequate expansion of the lung via positive pressure ventilation and progressive air suctioning with complete evacuation of the pneumothorax prior to the final closure (i.e., a purse string around the suction device), then the integrity of the closure could be proven using a bubble test with 500cc of saline placed at the diaphragm.

As the gynecologic surgeon studies Dr. Nezhat’s thorough discourse, it is obvious that, at times, a multidisciplinary team must be involved. Although possible, it would appear that risk of diaphragm paralysis secondary to injury of the phrenic nerve is indeed rare. This likely is because of the greater incidence of right-sided disease, rather than involving the central tendon, and lower likelihood that the lesion penetrates deeply. Nevertheless, a prudent multidisciplinary approach and knowledge of the anatomy will inevitably further reduce this rare complication.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He reported having no financial disclosures related to this column.

References

1. Proc R Soc Med. 1954 Jun; 47(6):461-8.

2. Surg Endosc. 2013 Feb;27(2):625-32.

The first case of diaphragmatic endometriosis was reported by Alan Brews in 19541. Unfortunately, no guidelines exist to enhance the recognition and treatment.

Diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis often is overlooked by the gynecologist, not only because of lack of appreciation of the symptoms but also because of the failure to properly work-up the patient and evaluate the diaphragm at time of surgery. In a retrospective review of 3,008 patients with pelvic endometriosis published in Surgical Endoscopy in 2013, Marcello Ceccaroni, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found 46 cases (1.53%) with the intraoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis, six with liver involvement. Multiple diaphragmatic endometriosis lesions were seen in 70% of patients and, the vast majority being right-sided lesions (87%), with 11% of cases having bilateral lesions.2 While in the study, superficial lesions were generally vaporized using the argon beam coagulator, deep lesions were removed by sharp dissection, highlighting the need to have adequately trained minimally invasive surgeons treating diaphragmatic lesions via incision. If a pneumothorax occurred, and reabsorbable suture was placed after adequate expansion of the lung via positive pressure ventilation and progressive air suctioning with complete evacuation of the pneumothorax prior to the final closure (i.e., a purse string around the suction device), then the integrity of the closure could be proven using a bubble test with 500cc of saline placed at the diaphragm.

As the gynecologic surgeon studies Dr. Nezhat’s thorough discourse, it is obvious that, at times, a multidisciplinary team must be involved. Although possible, it would appear that risk of diaphragm paralysis secondary to injury of the phrenic nerve is indeed rare. This likely is because of the greater incidence of right-sided disease, rather than involving the central tendon, and lower likelihood that the lesion penetrates deeply. Nevertheless, a prudent multidisciplinary approach and knowledge of the anatomy will inevitably further reduce this rare complication.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He reported having no financial disclosures related to this column.

References

1. Proc R Soc Med. 1954 Jun; 47(6):461-8.

2. Surg Endosc. 2013 Feb;27(2):625-32.

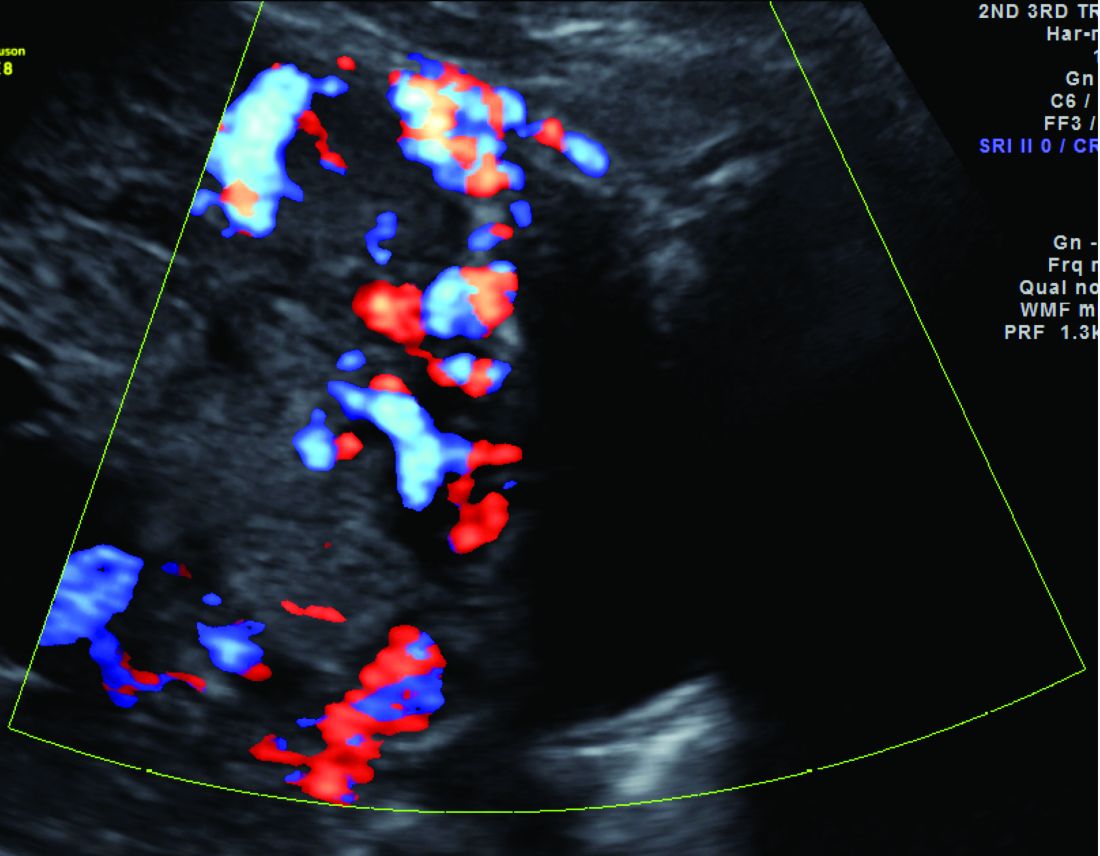

Diabetes’ social determinants: What they mean in our practices

More than many other pregnancy complications, diabetes exemplifies the impact of social determinants of health.

The medical management of diabetes during pregnancy involves major lifestyle changes. Diabetes care is largely a patient-driven social experience involving complex and demanding self-care behaviors and tasks.

The pregnant woman with diabetes is placed on a diet that is often novel to her and may be in conflict with the eating patterns of her family. She is advised to exercise, read nutrition labels, and purchase and cook healthy food. She often has to pick up prescriptions, check finger sticks and log results, accurately draw up insulin, and manage strict schedules.

Management requires a tremendous amount of daily engagement during a period of time that, in and of itself, is cognitively demanding.

Outcomes, in turn, are impacted by social context and social factors – by the patient’s economic stability and the safety and characteristics of her neighborhood, for instance, as well as her work schedule, her social support, and her level of health literacy. Each of these factors can influence behaviors and decision making, and ultimately glycemic control and perinatal outcomes.

The social determinants of diabetes-related health are so individualized and impactful that they must be realized and addressed throughout our care, from the way in which we communicate at the initial prenatal checkup to the support we offer for self-management.

Barriers to diabetes self-care