User login

The Dutch Medical Education

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the second article in that effort. Our first article, on the state of hospital medicine in Afghanistan, was published in the Jan. issue on p. 1.

For the first time in the Netherlands, the Free University of Amsterdam has appointed three professors in two non-university hospitals with a specific assignment for teaching. Until now, professors in such hospitals were appointed only for a specific research task that they perform in—or in close collaboration with—the university. In this article we describe the reasons and expectations for these appointments.

Medical Training in the Netherlands

Both undergraduate and postgraduate training in the Netherlands takes place in eight university medical centers. Although preclinical teaching is mainly a university domain, around two-thirds of the clinical training for interns and residents takes place in “affiliated” non-university teaching hospitals.

Until recently, medical education consisted of four years of preclinical studies and two years of clinical training. Now students are gradually admitted into the clinic during their first or second year of medical education. Further, the Dutch government has ruled that the number of first-year medical students must increase by 40. Both measures will result in a significant increase in the number of interns in the coming years.

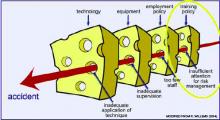

Because university hospitals presently accommodate the maximum number of interns they can take, the participation of non-university hospitals will rise considerably. However, their role must take into consideration not only quantity, but also quality. Because more than 90% of care in the Netherlands is delivered in non-university hospitals, these institutions provide the most proper setting for contextual learning. Adequate training is a prime barrier against accidents, so more resources must be invested in the quality of training programs in non-university hospitals to ensure the quality of future health care in the Netherlands.1,2 (See “Barriers Against Accidents,” p. 41.)

Teaching in Non-University Hospitals

By definition, medical education should be a core objective for teaching hospitals. (See “Requirements for Teaching Hospitals,” at right) This requires wide involvement by hospitals. Doctors in university hospitals generally have a contractual obligation to participate in teaching as part of their appointment. For most doctors in non-university hospitals, teaching is not part of their contract. Yet many of them do so on a voluntary basis. The advantage is that they are intrinsically motivated; however, the consequence is that they are not professional teachers, but rather well-meaning amateurs. This problem was recently addressed by the Central College for Medical Specialists, the ruling committee for specialist training in the Netherlands. Program directors and other specialists involved in teaching now take special courses to develop their teaching abilities.

Another issue involves defining end goals and planning curricula.3 For interns the goals are outlined in the “Blueprint for the Training of Medical Doctors in the Netherlands”; however, in practice, most internships are not structured, and learning opportunities depend on patient availability.4 It’s even questionable to what extent the precise curricular goals are known to interns and doctors alike.

For specialists, the end goals used to be inferred from practice, leaving lots of room for individual interpretation in the local institutions. These end goals are only now being defined. Many practical dilemmas, such as the relative weight we award to the various competencies, remain. For example, how much time should a surgical resident spend inside and outside the operating room? And what is the relative importance of experience? A key problem is that instruments that reliably measure the acquired competencies and the efficiency and efficacy of clinical training programs are still in their infancy.

Evidence-based teaching methods are now being demanded by the Central College for Medical Specialists. Methods include a modular-structured, competency-based curriculum, including regular skills, lab activities, and other training sessions, and the use of portfolios and mini clinical-evaluation exercises for formative and cumulative assessment.5,6

There are also practical problems on the working floor. In contrast to the preclinical teaching setting, which should be student-centered, the clinical environment of the hospital is primarily patient-centered. Interns and residents therefore have a double role: that of learner and care provider. These activities sometimes conflict, and the time allotted to each one is not clearly defined.

This became a greater problem after the restriction of resident working hours to 48 hours weekly in 1997. An attempt to divide these already strongly reduced hours to 36 “white-coat” hours and 12 “jacket” hours—purely dedicated to learning activities—has been abandoned.

In addition, the number of different parties on the working floor is sizable, and patients, nurses, medical staff, paramedics, and management often have different priorities, of which teaching is not always No. 1. Obviously such problems interfere with a structured, competency-based curriculum.

The Role of the Teaching Professor

In the Netherlands there is much work to do in the affiliated teaching hospitals, and a more professional approach is urgently needed. Professionalism, learning goals, curricula planning, evidence-based teaching methods, and solutions for practical problems that interfere with the proper implementation of evidence-based learning should all be addressed. The ruling committee and the professional organizations have set outlines that meet the requirements of modern times, but the elaboration and implementation have yet to be realized.

The Free University Medical Centre has taken the lead by appointing medical specialists as full professors with a specific assignment for teaching in non-university hospitals in order to develop and promote the teaching facilities in those institutions. They elected practicing non-university medical specialists with a demonstrable record in the field of education and an academic background comparable to that of university professors. Their assignment is to teach for one day a week. By doing so, they are not only putting teaching more prominently on the agenda, but also opening career perspectives that will promote a broader involvement in the development of educational programs.

The teaching professors develop and implement modern medical curricula and collaborate on research projects to evaluate the effectiveness of the new curricula in clinical teaching. Teaching professors also form a bridge between the university and the affiliated hospitals by transferring knowledge and ideas on medical education from the university to the non-university teaching hospitals—and vice versa. They also have input in the development of preclinical and clinical education programs from the point of view of the non-university hospital. For instance, they take part in the curriculum committee that advises on the bachelor’s and master’s programs, and they help create tests for the assessment of knowledge.

Summary

Non-university teaching hospitals have an essential place in the clinical phase of the medical curriculum in the Netherlands. A paradigm shift from the old master-mate relationship toward a structured, competency-based curriculum is taking place. Nomination of teaching professors in these institutions helps to create the professional structure that is mandatory for quality improvement in clinical teaching, and it also promotes the required interaction between university and non-university hospitals. TH

A.B. Bijnen works at the Foreest Institute, Medical Centre Almaar, the Netherlands; F. Scheele works at Sint Lucas Andreas Ziekenhuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and the Institute for Medical Education, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; A.E.R. Arnold also works at the Foreest Institute, as well as the Institute for Medical Education, Free University Medical Centre; A.M.J.J. Verweij works at the Sint Lucas Andreas Ziekenhuis, as well as the Institute for Medical Education at Free University Medical Centre; and H.J.M. van Rossum and J.A.A.M. van Diemen-Steenvoorde work at the Institute for Medical Education at Free University Medical Centre.

References

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768-770.

- Willems R. Sneller Beter—Hier werk je veilig, of je werkt hier niet. De veiligheid in de zorg. Eindrapportage Shell Nederland. November 2004.

- AMEE Education Guide No 14. Outcome-based education. 1999. ISBN: 1-903934-15-X.

- Metz JCM, Verbeek-Weel AMM, Huisjes HJ. Blueprint 2001: Training of doctors in The Netherlands. Adjusted objectives of undergraduate medical education in The Netherlands. Nijmegen: University Publication Office. 2001

- O’Connor HM, McGraw RC. Clinical skills training: developing objective assessment instruments. Med Educ. 1997;31:359-363.

- Davis MH, Harden RM. Competency-based assessment: making it a reality [editorial]. Med Teach. 2003;25:565-568.

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the second article in that effort. Our first article, on the state of hospital medicine in Afghanistan, was published in the Jan. issue on p. 1.

For the first time in the Netherlands, the Free University of Amsterdam has appointed three professors in two non-university hospitals with a specific assignment for teaching. Until now, professors in such hospitals were appointed only for a specific research task that they perform in—or in close collaboration with—the university. In this article we describe the reasons and expectations for these appointments.

Medical Training in the Netherlands

Both undergraduate and postgraduate training in the Netherlands takes place in eight university medical centers. Although preclinical teaching is mainly a university domain, around two-thirds of the clinical training for interns and residents takes place in “affiliated” non-university teaching hospitals.

Until recently, medical education consisted of four years of preclinical studies and two years of clinical training. Now students are gradually admitted into the clinic during their first or second year of medical education. Further, the Dutch government has ruled that the number of first-year medical students must increase by 40. Both measures will result in a significant increase in the number of interns in the coming years.

Because university hospitals presently accommodate the maximum number of interns they can take, the participation of non-university hospitals will rise considerably. However, their role must take into consideration not only quantity, but also quality. Because more than 90% of care in the Netherlands is delivered in non-university hospitals, these institutions provide the most proper setting for contextual learning. Adequate training is a prime barrier against accidents, so more resources must be invested in the quality of training programs in non-university hospitals to ensure the quality of future health care in the Netherlands.1,2 (See “Barriers Against Accidents,” p. 41.)

Teaching in Non-University Hospitals

By definition, medical education should be a core objective for teaching hospitals. (See “Requirements for Teaching Hospitals,” at right) This requires wide involvement by hospitals. Doctors in university hospitals generally have a contractual obligation to participate in teaching as part of their appointment. For most doctors in non-university hospitals, teaching is not part of their contract. Yet many of them do so on a voluntary basis. The advantage is that they are intrinsically motivated; however, the consequence is that they are not professional teachers, but rather well-meaning amateurs. This problem was recently addressed by the Central College for Medical Specialists, the ruling committee for specialist training in the Netherlands. Program directors and other specialists involved in teaching now take special courses to develop their teaching abilities.

Another issue involves defining end goals and planning curricula.3 For interns the goals are outlined in the “Blueprint for the Training of Medical Doctors in the Netherlands”; however, in practice, most internships are not structured, and learning opportunities depend on patient availability.4 It’s even questionable to what extent the precise curricular goals are known to interns and doctors alike.

For specialists, the end goals used to be inferred from practice, leaving lots of room for individual interpretation in the local institutions. These end goals are only now being defined. Many practical dilemmas, such as the relative weight we award to the various competencies, remain. For example, how much time should a surgical resident spend inside and outside the operating room? And what is the relative importance of experience? A key problem is that instruments that reliably measure the acquired competencies and the efficiency and efficacy of clinical training programs are still in their infancy.

Evidence-based teaching methods are now being demanded by the Central College for Medical Specialists. Methods include a modular-structured, competency-based curriculum, including regular skills, lab activities, and other training sessions, and the use of portfolios and mini clinical-evaluation exercises for formative and cumulative assessment.5,6

There are also practical problems on the working floor. In contrast to the preclinical teaching setting, which should be student-centered, the clinical environment of the hospital is primarily patient-centered. Interns and residents therefore have a double role: that of learner and care provider. These activities sometimes conflict, and the time allotted to each one is not clearly defined.

This became a greater problem after the restriction of resident working hours to 48 hours weekly in 1997. An attempt to divide these already strongly reduced hours to 36 “white-coat” hours and 12 “jacket” hours—purely dedicated to learning activities—has been abandoned.

In addition, the number of different parties on the working floor is sizable, and patients, nurses, medical staff, paramedics, and management often have different priorities, of which teaching is not always No. 1. Obviously such problems interfere with a structured, competency-based curriculum.

The Role of the Teaching Professor

In the Netherlands there is much work to do in the affiliated teaching hospitals, and a more professional approach is urgently needed. Professionalism, learning goals, curricula planning, evidence-based teaching methods, and solutions for practical problems that interfere with the proper implementation of evidence-based learning should all be addressed. The ruling committee and the professional organizations have set outlines that meet the requirements of modern times, but the elaboration and implementation have yet to be realized.

The Free University Medical Centre has taken the lead by appointing medical specialists as full professors with a specific assignment for teaching in non-university hospitals in order to develop and promote the teaching facilities in those institutions. They elected practicing non-university medical specialists with a demonstrable record in the field of education and an academic background comparable to that of university professors. Their assignment is to teach for one day a week. By doing so, they are not only putting teaching more prominently on the agenda, but also opening career perspectives that will promote a broader involvement in the development of educational programs.

The teaching professors develop and implement modern medical curricula and collaborate on research projects to evaluate the effectiveness of the new curricula in clinical teaching. Teaching professors also form a bridge between the university and the affiliated hospitals by transferring knowledge and ideas on medical education from the university to the non-university teaching hospitals—and vice versa. They also have input in the development of preclinical and clinical education programs from the point of view of the non-university hospital. For instance, they take part in the curriculum committee that advises on the bachelor’s and master’s programs, and they help create tests for the assessment of knowledge.

Summary

Non-university teaching hospitals have an essential place in the clinical phase of the medical curriculum in the Netherlands. A paradigm shift from the old master-mate relationship toward a structured, competency-based curriculum is taking place. Nomination of teaching professors in these institutions helps to create the professional structure that is mandatory for quality improvement in clinical teaching, and it also promotes the required interaction between university and non-university hospitals. TH

A.B. Bijnen works at the Foreest Institute, Medical Centre Almaar, the Netherlands; F. Scheele works at Sint Lucas Andreas Ziekenhuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and the Institute for Medical Education, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; A.E.R. Arnold also works at the Foreest Institute, as well as the Institute for Medical Education, Free University Medical Centre; A.M.J.J. Verweij works at the Sint Lucas Andreas Ziekenhuis, as well as the Institute for Medical Education at Free University Medical Centre; and H.J.M. van Rossum and J.A.A.M. van Diemen-Steenvoorde work at the Institute for Medical Education at Free University Medical Centre.

References

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768-770.

- Willems R. Sneller Beter—Hier werk je veilig, of je werkt hier niet. De veiligheid in de zorg. Eindrapportage Shell Nederland. November 2004.

- AMEE Education Guide No 14. Outcome-based education. 1999. ISBN: 1-903934-15-X.

- Metz JCM, Verbeek-Weel AMM, Huisjes HJ. Blueprint 2001: Training of doctors in The Netherlands. Adjusted objectives of undergraduate medical education in The Netherlands. Nijmegen: University Publication Office. 2001

- O’Connor HM, McGraw RC. Clinical skills training: developing objective assessment instruments. Med Educ. 1997;31:359-363.

- Davis MH, Harden RM. Competency-based assessment: making it a reality [editorial]. Med Teach. 2003;25:565-568.

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the second article in that effort. Our first article, on the state of hospital medicine in Afghanistan, was published in the Jan. issue on p. 1.

For the first time in the Netherlands, the Free University of Amsterdam has appointed three professors in two non-university hospitals with a specific assignment for teaching. Until now, professors in such hospitals were appointed only for a specific research task that they perform in—or in close collaboration with—the university. In this article we describe the reasons and expectations for these appointments.

Medical Training in the Netherlands

Both undergraduate and postgraduate training in the Netherlands takes place in eight university medical centers. Although preclinical teaching is mainly a university domain, around two-thirds of the clinical training for interns and residents takes place in “affiliated” non-university teaching hospitals.

Until recently, medical education consisted of four years of preclinical studies and two years of clinical training. Now students are gradually admitted into the clinic during their first or second year of medical education. Further, the Dutch government has ruled that the number of first-year medical students must increase by 40. Both measures will result in a significant increase in the number of interns in the coming years.

Because university hospitals presently accommodate the maximum number of interns they can take, the participation of non-university hospitals will rise considerably. However, their role must take into consideration not only quantity, but also quality. Because more than 90% of care in the Netherlands is delivered in non-university hospitals, these institutions provide the most proper setting for contextual learning. Adequate training is a prime barrier against accidents, so more resources must be invested in the quality of training programs in non-university hospitals to ensure the quality of future health care in the Netherlands.1,2 (See “Barriers Against Accidents,” p. 41.)

Teaching in Non-University Hospitals

By definition, medical education should be a core objective for teaching hospitals. (See “Requirements for Teaching Hospitals,” at right) This requires wide involvement by hospitals. Doctors in university hospitals generally have a contractual obligation to participate in teaching as part of their appointment. For most doctors in non-university hospitals, teaching is not part of their contract. Yet many of them do so on a voluntary basis. The advantage is that they are intrinsically motivated; however, the consequence is that they are not professional teachers, but rather well-meaning amateurs. This problem was recently addressed by the Central College for Medical Specialists, the ruling committee for specialist training in the Netherlands. Program directors and other specialists involved in teaching now take special courses to develop their teaching abilities.

Another issue involves defining end goals and planning curricula.3 For interns the goals are outlined in the “Blueprint for the Training of Medical Doctors in the Netherlands”; however, in practice, most internships are not structured, and learning opportunities depend on patient availability.4 It’s even questionable to what extent the precise curricular goals are known to interns and doctors alike.

For specialists, the end goals used to be inferred from practice, leaving lots of room for individual interpretation in the local institutions. These end goals are only now being defined. Many practical dilemmas, such as the relative weight we award to the various competencies, remain. For example, how much time should a surgical resident spend inside and outside the operating room? And what is the relative importance of experience? A key problem is that instruments that reliably measure the acquired competencies and the efficiency and efficacy of clinical training programs are still in their infancy.

Evidence-based teaching methods are now being demanded by the Central College for Medical Specialists. Methods include a modular-structured, competency-based curriculum, including regular skills, lab activities, and other training sessions, and the use of portfolios and mini clinical-evaluation exercises for formative and cumulative assessment.5,6

There are also practical problems on the working floor. In contrast to the preclinical teaching setting, which should be student-centered, the clinical environment of the hospital is primarily patient-centered. Interns and residents therefore have a double role: that of learner and care provider. These activities sometimes conflict, and the time allotted to each one is not clearly defined.

This became a greater problem after the restriction of resident working hours to 48 hours weekly in 1997. An attempt to divide these already strongly reduced hours to 36 “white-coat” hours and 12 “jacket” hours—purely dedicated to learning activities—has been abandoned.

In addition, the number of different parties on the working floor is sizable, and patients, nurses, medical staff, paramedics, and management often have different priorities, of which teaching is not always No. 1. Obviously such problems interfere with a structured, competency-based curriculum.

The Role of the Teaching Professor

In the Netherlands there is much work to do in the affiliated teaching hospitals, and a more professional approach is urgently needed. Professionalism, learning goals, curricula planning, evidence-based teaching methods, and solutions for practical problems that interfere with the proper implementation of evidence-based learning should all be addressed. The ruling committee and the professional organizations have set outlines that meet the requirements of modern times, but the elaboration and implementation have yet to be realized.

The Free University Medical Centre has taken the lead by appointing medical specialists as full professors with a specific assignment for teaching in non-university hospitals in order to develop and promote the teaching facilities in those institutions. They elected practicing non-university medical specialists with a demonstrable record in the field of education and an academic background comparable to that of university professors. Their assignment is to teach for one day a week. By doing so, they are not only putting teaching more prominently on the agenda, but also opening career perspectives that will promote a broader involvement in the development of educational programs.

The teaching professors develop and implement modern medical curricula and collaborate on research projects to evaluate the effectiveness of the new curricula in clinical teaching. Teaching professors also form a bridge between the university and the affiliated hospitals by transferring knowledge and ideas on medical education from the university to the non-university teaching hospitals—and vice versa. They also have input in the development of preclinical and clinical education programs from the point of view of the non-university hospital. For instance, they take part in the curriculum committee that advises on the bachelor’s and master’s programs, and they help create tests for the assessment of knowledge.

Summary

Non-university teaching hospitals have an essential place in the clinical phase of the medical curriculum in the Netherlands. A paradigm shift from the old master-mate relationship toward a structured, competency-based curriculum is taking place. Nomination of teaching professors in these institutions helps to create the professional structure that is mandatory for quality improvement in clinical teaching, and it also promotes the required interaction between university and non-university hospitals. TH

A.B. Bijnen works at the Foreest Institute, Medical Centre Almaar, the Netherlands; F. Scheele works at Sint Lucas Andreas Ziekenhuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and the Institute for Medical Education, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; A.E.R. Arnold also works at the Foreest Institute, as well as the Institute for Medical Education, Free University Medical Centre; A.M.J.J. Verweij works at the Sint Lucas Andreas Ziekenhuis, as well as the Institute for Medical Education at Free University Medical Centre; and H.J.M. van Rossum and J.A.A.M. van Diemen-Steenvoorde work at the Institute for Medical Education at Free University Medical Centre.

References

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768-770.

- Willems R. Sneller Beter—Hier werk je veilig, of je werkt hier niet. De veiligheid in de zorg. Eindrapportage Shell Nederland. November 2004.

- AMEE Education Guide No 14. Outcome-based education. 1999. ISBN: 1-903934-15-X.

- Metz JCM, Verbeek-Weel AMM, Huisjes HJ. Blueprint 2001: Training of doctors in The Netherlands. Adjusted objectives of undergraduate medical education in The Netherlands. Nijmegen: University Publication Office. 2001

- O’Connor HM, McGraw RC. Clinical skills training: developing objective assessment instruments. Med Educ. 1997;31:359-363.

- Davis MH, Harden RM. Competency-based assessment: making it a reality [editorial]. Med Teach. 2003;25:565-568.