User login

Managing incontinence: A 2-visit approach

• Advise the patient to complete a 3-day voiding diary, which will help you categorize and determine the cause and severity of her incontinence. B

• Recommend Kegel exercises for stress incontinence; provide instruction in technique and/or a referral for pelvic floor physical therapy for instruction. A

• Try an anticholinergic medication with indications for urinary incontinence for women with primarily urge-type incontinence. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

PATIENT HANDOUT

Voiding diary: What it’s for, how to fill it out

Visit #1: Simple steps to take right away

When a patient confides that she suffers from urinary incontinence, even if it’s near the end of her visit, there are 3 critical steps that can be taken without delay:

- Collect a urine sample for urinalysis (if the patient is capable of providing a clean-catch sample and did not already do so at the start of the visit).

- Ask her to keep a voiding diary for 3 days, using the clip-and-copy patient handout. (Tech-savvy patients may prefer to use the voiding diary app available at no charge at http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/bladder-pal/id435763473?mt=8.) Review the instructions for filling out the voiding diary with the patient, or have a nurse or medical assistant do so. Call the patient’s attention to the numerical (1-4) formula recommended for approximating the quantity of urine lost in an episode of incontinence, as this is often the component of the diary that patients have the most trouble with. 7

- Schedule a follow-up visit. If the urinalysis shows that the patient has a urinary tract infection, initiate treatment as soon as possible. Treatment should be completed by the time she arrives for visit#2 so that her incontinence can be reassessed in the absence of infection.

Tell your patient to bring the completed voiding diary to this visit and to avoid emptying her bladder before she sees you. When the patient checks in, she should be reminded again not to urinate until you have completed the examination.

What to do during Visit #2

This visit will begin with a targeted assessment to determine what type of incontinence the patient has and whether you should initiate treatment or refer her to a specialist.

Start with a targeted history and review of the voiding diary

Ask the patient about timing, quantity, and the overall circumstances of typical incontinence episodes, as well as the incidents that she finds most troubling. A medication history should be included, with information not only about what she’s taking, but also about when she takes her medications. A careful review of the voiding diary will provide additional information, including fluid intake quantity and quality (eg, caffeine or alcohol) and urinary frequency, quantity, and timing.

The initial goal is to classify her incontinence as urge (occurring simultaneously with, or right after, a strong feeling of the need to void); stress (the result of an acute increase in abdominal pressure, typically associated with a physical act such as coughing, sneezing, bending over, heavy lifting, or starting to run); or mixed, which involves some episodes of both.8 “High-yield” questions like the ones that follow are particularly helpful in pinpointing the type of incontinence and guiding treatment decisions:

- Do you worry about leakage when you cough or sneeze? (Stress incontinence.)

- When your bladder is full, do you typically have to stop what you’re doing and go right away, or can you wait until a convenient time to find a bathroom? (Urge incontinence.)

And, for patients who report both stress and urge episodes (mixed incontinence):

- Which is more upsetting to you: leakage that occurs when you cough or sneeze or the inability to wait until it’s convenient to get to a bathroom?

A pelvic exam and cough stress test

Next, perform a pelvic examination and assess the following:

External genitalia. Look for signs of chronic urine exposure (eg, erythema, skin breakdown) and urethral abnormalities.

Cystoceles or rectoceles. Ask the patient to bear down strongly to allow you to visualize cystoceles and rectoceles, which usually present as a significant bulging of the tissues of the anterior or posterior vaginal walls. Reassure her that urine leakage and flatus are completely acceptable—and expected—during this part of the exam.

Pelvic mass. Palpate for evidence of a pelvic mass, which can cause urinary obstruction and lead to overflow incontinence.

Kegel exercises. Ask her to perform a Kegel maneuver. If she’s doing it correctly, her perineal body should be easily seen moving upward toward her clitoris and inward toward her introitus. If you place a finger in the vagina and ask her to begin Kegel exercises, you’ll feel the tightening of the pelvic muscles if she’s doing it right. When she does this on her own, she can insert her own finger into the vagina to ensure that her technique is correct or simply practice stopping the flow of urine.

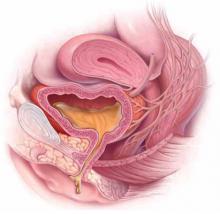

After completing the pelvic exam, perform a cough stress test. With the patient in the lithotomy position, ask her to cough while you hold the labia apart, both to observe for any leakage of urine and to approximate the volume leaked, if any ( FIGURE ). To encourage her to bear down with ample force, remind her that here, too, both leakage of urine and passing of flatus are expected.

Postvoid residual (PVr). After the pelvic exam and cough stress test, the patient should urinate and the PVR should be promptly measured. If you have doubts about her ability to provide a clean-catch urine sample (or your clinic does not have a bladder scanning ultrasound), consider obtaining the PVR via a straight catheterization. A normal PVR is 0 to 200 cc.

By now you should have the information you need to determine whether to treat the incontinence yourself or refer the patient to a urologist or urogynecologist.

FIGURE

Positive cough stress test

A physician separates the labia to observe urine leakage during a cough stress test.

Treat these conditions yourself

Dx: Uncomplicated stress incontinence. The patient has a positive cough stress test, and most urinary incontinence episodes she recorded are stress type. Urinalysis and PVR are normal, with no evidence of pelvic organ prolapse on exam.

Well-timed pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises have been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of both stress and urge incontinence when they’re done regularly, starting with 4 times a day and increased slowly to 8 times twice a day.9 Review Kegel technique and advise the patient to perform this maneuver and hold the contraction, if possible, whenever she is about to cough, laugh, sneeze, or otherwise exert herself. Tell her to practice Kegel exercises until they become second nature. If she continues to have trouble, she may need a referral to pelvic floor physical therapy to learn to do them effectively. (You can go to http://www.apta.org/apta/findapt/index.aspx?navID=10737422525 to find a therapist specializing in women’s health in your area.)

Dx: Uncomplicated urge incontinence. The patient has a normal cough stress test and most of her urinary incontinence episodes are the urge type. Her pelvic exam and PVR are within normal limits.

Prescribe an anticholinergic bladder agent. Medication with antimuscarinic properties has been shown to decrease urge incontinence and significantly improve patient-reported measures of quality of life.10

A reasonable approach is to start her on an inexpensive generic medication ( TABLE )11,12 and follow up in one month. If the medication helps and does not cause adverse effects, she can be maintained on it; if it’s effective but she has significant adverse effects (eg, constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, as well as confusion and sedation in the elderly), the patient can be switched to a more expensive brand-name drug with fewer adverse effects.

Behavioral training, including timed voiding and Kegel exercises, has been shown to significantly decrease symptoms of urge incontinence.9 Timed voiding can be especially helpful for nocturnal urge incontinence; advise the patient to set an alarm for an hour before the usual time she awakens with a sense of urgency, and to empty her bladder before it is so full that she leaks.

Point out, too, that not every urinary urge requires immediately running to the toilet. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that patients who were taught to respond to visual cues, such as a toilet, by walking past it, then sitting down, relaxing, and contracting their pelvic muscles repeatedly had diminished urgency. Their actions also inhibited detrusor contractions, and often prevented urine loss. When the training was combined with one or 2 lessons in proper Kegel technique—reinforced at several visits—weekly incontinence episodes were reduced by 80%. The controls, who had the same number of clinic visits but did not receive specific education on urgency-reduction strategies, reduced incontinence episodes by 40%.13

Dx: Fluid overuse. The patient is drinking an excessive quantity of fluid, as evidenced by urine volume >2100 cc. (The International Continence Society defines polyuria as >40 mL/kg per day.14 )

Advise the patient to decrease her overall fluid intake, particularly within several hours of bedtime. Studies of tea and coffee consumption and incontinence have had conflicting results,15,16 and data on caffeinated soda consumption and incontinence are lacking. Nonetheless, patients should be advised that there is a possible association between caffeinated beverages and urinary incontinence. (In one small study, caffeine was found to cause a significant increase in detrusor pressure.17 ) Giving women one-time general instructions on fluid intake modification has been shown to significantly decrease incontinence episodes.18

Dx: Badly timed medication intake. This patient is taking one or more drugs that may contribute to incontinence, such as alpha-blockers or diuretics, either shortly before going to bed or before activities that make a bathroom visit inconvenient or impossible.

Adjust her medication regimen to minimize nocturia or urinary urgency during times of peak activity—eg, taking a diuretic early in the day instead of in the afternoon or evening, if possible. Keep in mind, however, that this strategy is based primarily on expert opinion, as very little evidence exists to show that medication of any type has a significant effect on urinary continence.19

Dx: Lower extremity edema with postural diuresis. The patient has nocturia, with larger total urine output at night than during the day. She may or may not have some leakage.

Women with lower extremity edema due to a variety of medical causes often experience postural diuresis overnight. If the patient is already on a diuretic, the problem can often be ameliorated by taking it early in the day instead of in the afternoon or evening; if she’s not, prescribe a small dose of a diuretic, to be taken in the morning. This therapeutic intervention has not been rigorously studied, but is relatively easy to implement and worth a try for patients with heart failure or other causes of pedal edema.

Dx: Constipation associated with autonomic dysfunction. Because the rectum and bladder are controlled by the same sacral segments of the spinal cord and share many autonomic ganglia, problems in one compartment often affect another. In a patient for whom incontinence is a minor, or occasional, problem while constipation is a major complaint, the optimal approach is to treat the constipation first and see if the urinary incontinence also resolves.

A trial of polyethylene glycol is a good place to start, particularly if there is no evidence of another correctable cause of the incontinence. Studies have shown that successful treatment of constipation often results in significant improvement of urinary urgency and frequency.20

TABLE

Anticholinergic medications for urge incontinence11,12

| Medication | Dosing | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Oxybutynin | 2.5-5 mg bid to tid (≤5 mg qid) | Significant adverse effects, including constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention; confusion and sedation, particularly in elderly |

| Oxybutynin ER | 5-10 mg/d; increase weekly by 5-mg/d increments to ≤30 mg/d | |

| Oxybutynin transdermal patch (Oxytrol) | 1 patch 2x/wk on abdomen, hips, or buttocks (dose=3.9 mg/d) | Adverse effects may be less frequent than with oral medication due to the avoidance of metabolites |

| Oxybutynin transdermal gel (Gelnique) | 1 gel pack/d on abdomen, thighs, or shoulders (dose=100 mg in 1-g gel pack) | |

| Tolterodine (Detrol) | 1-2 mg bid (immediate release) or 2-4 mg/d (ER) | Similar effects and efficacy as oxybutynin, but adverse effects are decreased due to greater uroselectivity on muscarinic receptors |

| Darifenacin hydrobromide (Enablex) | 7.5 mg/d; increase to 15 mg/d after 2 wk if necessary | |

| Solifenacin (VESIcare) | 5-10 mg/d | |

| Fesoteridine (Toviaz) | 4-8 mg/d | |

| Trospium (Sanctura) | 20 mg bid (immediate release) or 60 mg/d (ER) | |

| ER, extended release. | ||

These conditions typically warrant a referral

Dx: Hematuria. Urinalysis with hematuria but no evidence of a urinary tract infection should raise a red flag, regardless of other findings. The patient should be referred for further urologic evaluation, including cystoscopy, although you may want to repeat the urinalysis with another clean-catch specimen first. Straight catheterization is not recommended in such a case, as a traumatized urethra can be a source of hematuria.

Dx: Stress incontinence with an anatomic abnormality. There are 2 options for a patient who has stress incontinence with an obvious cystocele on exam: Fit her with a pessary (or refer her to a physician who has this capability), or provide a referral to a urogynecologist for corrective surgery. Which option to choose should be a collaborative decision between patient and physician. For most women, it makes sense to try the pessary first.

Dx: Urinary retention. A patient with a high normal or elevated PVR (>100-200 cc) and no obvious pelvic organ prolapse needs a work-up for urinary retention. There is a broad differential that can be divided into neurologic, obstructive, and pharmacologic etiologies.21 A referral is indicated so that a urologist can oversee the work-up.

Particularly worrisome causes of urinary retention are multiple sclerosis, which is more likely in a relatively young, otherwise healthy woman, and a pelvic mass. Medications are also a likely cause. The list of drugs that can induce urinary retention is extensive, and includes anticholinergics, antidepressants (tricyclics and some heterocyclics), antihistamines, and muscle relaxants, among others. If you’re unable to find a likely cause, a referral is indicated so that a urologist can oversee the work-up.

CORRESPONDENCE Abigail Lowther, MD, University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine, 24 Frank Lloyd Wright Drive, Lobby H, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-5795; abigaill@med.umich.edu

1. Hunskaar S, Lose G, Sykes D, et al. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int 2004;93:324-330.

2. Roberts RO, Jacobsen SJ, Rhodes T, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community-based cohort: prevalence and healthcare-seeking. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:467-472.

3. Markland AD, Richter HE, Chyng-Wen F, et al. Prevalence and trends of urinary incontinence in adults in the United States, 2001-2008. J Urol 2011;186:589-593.

4. Kinchen KS, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. Factors associated with women’s decisions to seek treatment for urinary incontinence. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:687-698.

5. O’Donnell M, Viktrup L, Hunskaar S. The role of general practitioners in the initial management of women with urinary incontinence in France, Germany, Spain and the UK. Eur J Gen Pract 2007;13:20-26.

6. Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle PG, et al. A practice-based intervention to improve primary care for falls, urinary incontinence, and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:547-555.

7. Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, Carchidi LT, et al. On the lack of correlation between self-report and urine loss measured with standing provocation test in older stress-incontinent women. J Womens Health 1999;8:157-162.

8. Deng DY. Urinary incontinence in women. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:101-109.

9. Nygaard IE, Kreder KJ, Lepic MM, et al. Efficacy of pelvic floor muscle exercises in women with stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:120-125.

10. Van Kerrebroeck PE, Kelleher CJ, Coyne KS, et al. Correlations among improvements in urgency urinary incontinence, health-related quality of life, and perception of bladder-related problems in incontinent subjects with overactive bladder treated with tolterodine or placebo. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:13-18.

11. Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Burgio KL, et al. Urinary incontinence in older adults. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:558-570.

12. Davila GW, Starkman JS, Dmochowski RR. Transdermal oxybutynin for overactive bladder. Urol Clin North Am 2006;33:455-463.

13. Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1995-2000.

14. Homma Y. Lower urinary tract symptomatology: its definition and confusion. J Urol 2008;15:35-43.

15. Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, et al. Are smoking and other lifestyle factors associated with female urinary incontinence? The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. BJOG. 2003;110:247-254.

16. Hirayama F, Lee AH. Green tea drinking is inversely associated with urinary incontinence in middle-aged and older women. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30:1262-1265.

17. Creighton SM, Stanton SL. Caffeine: does it affect your bladder? Br J Urol 1990;66:613-614

18. Zimmern P, Litman HJ, Mueller E, et al. Effect of fluid management on fluid intake and urge incontinence in a trial for overactive bladder in women. BJU Int. 2010;105:1680-1685.

19. Tsakiris P, Oelke M, Michel MC. Drug-induced urinary incontinence. Drugs Aging 2008;25:541-549.

20. Wyman JF, Burgio KL, Newman DK. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:1177-1191.

21. Selius B, Subedi R. Urinary retention in adults: diagnosis and initial management. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:643-650.

• Advise the patient to complete a 3-day voiding diary, which will help you categorize and determine the cause and severity of her incontinence. B

• Recommend Kegel exercises for stress incontinence; provide instruction in technique and/or a referral for pelvic floor physical therapy for instruction. A

• Try an anticholinergic medication with indications for urinary incontinence for women with primarily urge-type incontinence. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

PATIENT HANDOUT

Voiding diary: What it’s for, how to fill it out

Visit #1: Simple steps to take right away

When a patient confides that she suffers from urinary incontinence, even if it’s near the end of her visit, there are 3 critical steps that can be taken without delay:

- Collect a urine sample for urinalysis (if the patient is capable of providing a clean-catch sample and did not already do so at the start of the visit).

- Ask her to keep a voiding diary for 3 days, using the clip-and-copy patient handout. (Tech-savvy patients may prefer to use the voiding diary app available at no charge at http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/bladder-pal/id435763473?mt=8.) Review the instructions for filling out the voiding diary with the patient, or have a nurse or medical assistant do so. Call the patient’s attention to the numerical (1-4) formula recommended for approximating the quantity of urine lost in an episode of incontinence, as this is often the component of the diary that patients have the most trouble with. 7

- Schedule a follow-up visit. If the urinalysis shows that the patient has a urinary tract infection, initiate treatment as soon as possible. Treatment should be completed by the time she arrives for visit#2 so that her incontinence can be reassessed in the absence of infection.

Tell your patient to bring the completed voiding diary to this visit and to avoid emptying her bladder before she sees you. When the patient checks in, she should be reminded again not to urinate until you have completed the examination.

What to do during Visit #2

This visit will begin with a targeted assessment to determine what type of incontinence the patient has and whether you should initiate treatment or refer her to a specialist.

Start with a targeted history and review of the voiding diary

Ask the patient about timing, quantity, and the overall circumstances of typical incontinence episodes, as well as the incidents that she finds most troubling. A medication history should be included, with information not only about what she’s taking, but also about when she takes her medications. A careful review of the voiding diary will provide additional information, including fluid intake quantity and quality (eg, caffeine or alcohol) and urinary frequency, quantity, and timing.

The initial goal is to classify her incontinence as urge (occurring simultaneously with, or right after, a strong feeling of the need to void); stress (the result of an acute increase in abdominal pressure, typically associated with a physical act such as coughing, sneezing, bending over, heavy lifting, or starting to run); or mixed, which involves some episodes of both.8 “High-yield” questions like the ones that follow are particularly helpful in pinpointing the type of incontinence and guiding treatment decisions:

- Do you worry about leakage when you cough or sneeze? (Stress incontinence.)

- When your bladder is full, do you typically have to stop what you’re doing and go right away, or can you wait until a convenient time to find a bathroom? (Urge incontinence.)

And, for patients who report both stress and urge episodes (mixed incontinence):

- Which is more upsetting to you: leakage that occurs when you cough or sneeze or the inability to wait until it’s convenient to get to a bathroom?

A pelvic exam and cough stress test

Next, perform a pelvic examination and assess the following:

External genitalia. Look for signs of chronic urine exposure (eg, erythema, skin breakdown) and urethral abnormalities.

Cystoceles or rectoceles. Ask the patient to bear down strongly to allow you to visualize cystoceles and rectoceles, which usually present as a significant bulging of the tissues of the anterior or posterior vaginal walls. Reassure her that urine leakage and flatus are completely acceptable—and expected—during this part of the exam.

Pelvic mass. Palpate for evidence of a pelvic mass, which can cause urinary obstruction and lead to overflow incontinence.

Kegel exercises. Ask her to perform a Kegel maneuver. If she’s doing it correctly, her perineal body should be easily seen moving upward toward her clitoris and inward toward her introitus. If you place a finger in the vagina and ask her to begin Kegel exercises, you’ll feel the tightening of the pelvic muscles if she’s doing it right. When she does this on her own, she can insert her own finger into the vagina to ensure that her technique is correct or simply practice stopping the flow of urine.

After completing the pelvic exam, perform a cough stress test. With the patient in the lithotomy position, ask her to cough while you hold the labia apart, both to observe for any leakage of urine and to approximate the volume leaked, if any ( FIGURE ). To encourage her to bear down with ample force, remind her that here, too, both leakage of urine and passing of flatus are expected.

Postvoid residual (PVr). After the pelvic exam and cough stress test, the patient should urinate and the PVR should be promptly measured. If you have doubts about her ability to provide a clean-catch urine sample (or your clinic does not have a bladder scanning ultrasound), consider obtaining the PVR via a straight catheterization. A normal PVR is 0 to 200 cc.

By now you should have the information you need to determine whether to treat the incontinence yourself or refer the patient to a urologist or urogynecologist.

FIGURE

Positive cough stress test

A physician separates the labia to observe urine leakage during a cough stress test.

Treat these conditions yourself

Dx: Uncomplicated stress incontinence. The patient has a positive cough stress test, and most urinary incontinence episodes she recorded are stress type. Urinalysis and PVR are normal, with no evidence of pelvic organ prolapse on exam.

Well-timed pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises have been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of both stress and urge incontinence when they’re done regularly, starting with 4 times a day and increased slowly to 8 times twice a day.9 Review Kegel technique and advise the patient to perform this maneuver and hold the contraction, if possible, whenever she is about to cough, laugh, sneeze, or otherwise exert herself. Tell her to practice Kegel exercises until they become second nature. If she continues to have trouble, she may need a referral to pelvic floor physical therapy to learn to do them effectively. (You can go to http://www.apta.org/apta/findapt/index.aspx?navID=10737422525 to find a therapist specializing in women’s health in your area.)

Dx: Uncomplicated urge incontinence. The patient has a normal cough stress test and most of her urinary incontinence episodes are the urge type. Her pelvic exam and PVR are within normal limits.

Prescribe an anticholinergic bladder agent. Medication with antimuscarinic properties has been shown to decrease urge incontinence and significantly improve patient-reported measures of quality of life.10

A reasonable approach is to start her on an inexpensive generic medication ( TABLE )11,12 and follow up in one month. If the medication helps and does not cause adverse effects, she can be maintained on it; if it’s effective but she has significant adverse effects (eg, constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, as well as confusion and sedation in the elderly), the patient can be switched to a more expensive brand-name drug with fewer adverse effects.

Behavioral training, including timed voiding and Kegel exercises, has been shown to significantly decrease symptoms of urge incontinence.9 Timed voiding can be especially helpful for nocturnal urge incontinence; advise the patient to set an alarm for an hour before the usual time she awakens with a sense of urgency, and to empty her bladder before it is so full that she leaks.

Point out, too, that not every urinary urge requires immediately running to the toilet. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that patients who were taught to respond to visual cues, such as a toilet, by walking past it, then sitting down, relaxing, and contracting their pelvic muscles repeatedly had diminished urgency. Their actions also inhibited detrusor contractions, and often prevented urine loss. When the training was combined with one or 2 lessons in proper Kegel technique—reinforced at several visits—weekly incontinence episodes were reduced by 80%. The controls, who had the same number of clinic visits but did not receive specific education on urgency-reduction strategies, reduced incontinence episodes by 40%.13

Dx: Fluid overuse. The patient is drinking an excessive quantity of fluid, as evidenced by urine volume >2100 cc. (The International Continence Society defines polyuria as >40 mL/kg per day.14 )

Advise the patient to decrease her overall fluid intake, particularly within several hours of bedtime. Studies of tea and coffee consumption and incontinence have had conflicting results,15,16 and data on caffeinated soda consumption and incontinence are lacking. Nonetheless, patients should be advised that there is a possible association between caffeinated beverages and urinary incontinence. (In one small study, caffeine was found to cause a significant increase in detrusor pressure.17 ) Giving women one-time general instructions on fluid intake modification has been shown to significantly decrease incontinence episodes.18

Dx: Badly timed medication intake. This patient is taking one or more drugs that may contribute to incontinence, such as alpha-blockers or diuretics, either shortly before going to bed or before activities that make a bathroom visit inconvenient or impossible.

Adjust her medication regimen to minimize nocturia or urinary urgency during times of peak activity—eg, taking a diuretic early in the day instead of in the afternoon or evening, if possible. Keep in mind, however, that this strategy is based primarily on expert opinion, as very little evidence exists to show that medication of any type has a significant effect on urinary continence.19

Dx: Lower extremity edema with postural diuresis. The patient has nocturia, with larger total urine output at night than during the day. She may or may not have some leakage.

Women with lower extremity edema due to a variety of medical causes often experience postural diuresis overnight. If the patient is already on a diuretic, the problem can often be ameliorated by taking it early in the day instead of in the afternoon or evening; if she’s not, prescribe a small dose of a diuretic, to be taken in the morning. This therapeutic intervention has not been rigorously studied, but is relatively easy to implement and worth a try for patients with heart failure or other causes of pedal edema.

Dx: Constipation associated with autonomic dysfunction. Because the rectum and bladder are controlled by the same sacral segments of the spinal cord and share many autonomic ganglia, problems in one compartment often affect another. In a patient for whom incontinence is a minor, or occasional, problem while constipation is a major complaint, the optimal approach is to treat the constipation first and see if the urinary incontinence also resolves.

A trial of polyethylene glycol is a good place to start, particularly if there is no evidence of another correctable cause of the incontinence. Studies have shown that successful treatment of constipation often results in significant improvement of urinary urgency and frequency.20

TABLE

Anticholinergic medications for urge incontinence11,12

| Medication | Dosing | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Oxybutynin | 2.5-5 mg bid to tid (≤5 mg qid) | Significant adverse effects, including constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention; confusion and sedation, particularly in elderly |

| Oxybutynin ER | 5-10 mg/d; increase weekly by 5-mg/d increments to ≤30 mg/d | |

| Oxybutynin transdermal patch (Oxytrol) | 1 patch 2x/wk on abdomen, hips, or buttocks (dose=3.9 mg/d) | Adverse effects may be less frequent than with oral medication due to the avoidance of metabolites |

| Oxybutynin transdermal gel (Gelnique) | 1 gel pack/d on abdomen, thighs, or shoulders (dose=100 mg in 1-g gel pack) | |

| Tolterodine (Detrol) | 1-2 mg bid (immediate release) or 2-4 mg/d (ER) | Similar effects and efficacy as oxybutynin, but adverse effects are decreased due to greater uroselectivity on muscarinic receptors |

| Darifenacin hydrobromide (Enablex) | 7.5 mg/d; increase to 15 mg/d after 2 wk if necessary | |

| Solifenacin (VESIcare) | 5-10 mg/d | |

| Fesoteridine (Toviaz) | 4-8 mg/d | |

| Trospium (Sanctura) | 20 mg bid (immediate release) or 60 mg/d (ER) | |

| ER, extended release. | ||

These conditions typically warrant a referral

Dx: Hematuria. Urinalysis with hematuria but no evidence of a urinary tract infection should raise a red flag, regardless of other findings. The patient should be referred for further urologic evaluation, including cystoscopy, although you may want to repeat the urinalysis with another clean-catch specimen first. Straight catheterization is not recommended in such a case, as a traumatized urethra can be a source of hematuria.

Dx: Stress incontinence with an anatomic abnormality. There are 2 options for a patient who has stress incontinence with an obvious cystocele on exam: Fit her with a pessary (or refer her to a physician who has this capability), or provide a referral to a urogynecologist for corrective surgery. Which option to choose should be a collaborative decision between patient and physician. For most women, it makes sense to try the pessary first.

Dx: Urinary retention. A patient with a high normal or elevated PVR (>100-200 cc) and no obvious pelvic organ prolapse needs a work-up for urinary retention. There is a broad differential that can be divided into neurologic, obstructive, and pharmacologic etiologies.21 A referral is indicated so that a urologist can oversee the work-up.

Particularly worrisome causes of urinary retention are multiple sclerosis, which is more likely in a relatively young, otherwise healthy woman, and a pelvic mass. Medications are also a likely cause. The list of drugs that can induce urinary retention is extensive, and includes anticholinergics, antidepressants (tricyclics and some heterocyclics), antihistamines, and muscle relaxants, among others. If you’re unable to find a likely cause, a referral is indicated so that a urologist can oversee the work-up.

CORRESPONDENCE Abigail Lowther, MD, University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine, 24 Frank Lloyd Wright Drive, Lobby H, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-5795; abigaill@med.umich.edu

• Advise the patient to complete a 3-day voiding diary, which will help you categorize and determine the cause and severity of her incontinence. B

• Recommend Kegel exercises for stress incontinence; provide instruction in technique and/or a referral for pelvic floor physical therapy for instruction. A

• Try an anticholinergic medication with indications for urinary incontinence for women with primarily urge-type incontinence. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

PATIENT HANDOUT

Voiding diary: What it’s for, how to fill it out

Visit #1: Simple steps to take right away

When a patient confides that she suffers from urinary incontinence, even if it’s near the end of her visit, there are 3 critical steps that can be taken without delay:

- Collect a urine sample for urinalysis (if the patient is capable of providing a clean-catch sample and did not already do so at the start of the visit).

- Ask her to keep a voiding diary for 3 days, using the clip-and-copy patient handout. (Tech-savvy patients may prefer to use the voiding diary app available at no charge at http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/bladder-pal/id435763473?mt=8.) Review the instructions for filling out the voiding diary with the patient, or have a nurse or medical assistant do so. Call the patient’s attention to the numerical (1-4) formula recommended for approximating the quantity of urine lost in an episode of incontinence, as this is often the component of the diary that patients have the most trouble with. 7

- Schedule a follow-up visit. If the urinalysis shows that the patient has a urinary tract infection, initiate treatment as soon as possible. Treatment should be completed by the time she arrives for visit#2 so that her incontinence can be reassessed in the absence of infection.

Tell your patient to bring the completed voiding diary to this visit and to avoid emptying her bladder before she sees you. When the patient checks in, she should be reminded again not to urinate until you have completed the examination.

What to do during Visit #2

This visit will begin with a targeted assessment to determine what type of incontinence the patient has and whether you should initiate treatment or refer her to a specialist.

Start with a targeted history and review of the voiding diary

Ask the patient about timing, quantity, and the overall circumstances of typical incontinence episodes, as well as the incidents that she finds most troubling. A medication history should be included, with information not only about what she’s taking, but also about when she takes her medications. A careful review of the voiding diary will provide additional information, including fluid intake quantity and quality (eg, caffeine or alcohol) and urinary frequency, quantity, and timing.

The initial goal is to classify her incontinence as urge (occurring simultaneously with, or right after, a strong feeling of the need to void); stress (the result of an acute increase in abdominal pressure, typically associated with a physical act such as coughing, sneezing, bending over, heavy lifting, or starting to run); or mixed, which involves some episodes of both.8 “High-yield” questions like the ones that follow are particularly helpful in pinpointing the type of incontinence and guiding treatment decisions:

- Do you worry about leakage when you cough or sneeze? (Stress incontinence.)

- When your bladder is full, do you typically have to stop what you’re doing and go right away, or can you wait until a convenient time to find a bathroom? (Urge incontinence.)

And, for patients who report both stress and urge episodes (mixed incontinence):

- Which is more upsetting to you: leakage that occurs when you cough or sneeze or the inability to wait until it’s convenient to get to a bathroom?

A pelvic exam and cough stress test

Next, perform a pelvic examination and assess the following:

External genitalia. Look for signs of chronic urine exposure (eg, erythema, skin breakdown) and urethral abnormalities.

Cystoceles or rectoceles. Ask the patient to bear down strongly to allow you to visualize cystoceles and rectoceles, which usually present as a significant bulging of the tissues of the anterior or posterior vaginal walls. Reassure her that urine leakage and flatus are completely acceptable—and expected—during this part of the exam.

Pelvic mass. Palpate for evidence of a pelvic mass, which can cause urinary obstruction and lead to overflow incontinence.

Kegel exercises. Ask her to perform a Kegel maneuver. If she’s doing it correctly, her perineal body should be easily seen moving upward toward her clitoris and inward toward her introitus. If you place a finger in the vagina and ask her to begin Kegel exercises, you’ll feel the tightening of the pelvic muscles if she’s doing it right. When she does this on her own, she can insert her own finger into the vagina to ensure that her technique is correct or simply practice stopping the flow of urine.

After completing the pelvic exam, perform a cough stress test. With the patient in the lithotomy position, ask her to cough while you hold the labia apart, both to observe for any leakage of urine and to approximate the volume leaked, if any ( FIGURE ). To encourage her to bear down with ample force, remind her that here, too, both leakage of urine and passing of flatus are expected.

Postvoid residual (PVr). After the pelvic exam and cough stress test, the patient should urinate and the PVR should be promptly measured. If you have doubts about her ability to provide a clean-catch urine sample (or your clinic does not have a bladder scanning ultrasound), consider obtaining the PVR via a straight catheterization. A normal PVR is 0 to 200 cc.

By now you should have the information you need to determine whether to treat the incontinence yourself or refer the patient to a urologist or urogynecologist.

FIGURE

Positive cough stress test

A physician separates the labia to observe urine leakage during a cough stress test.

Treat these conditions yourself

Dx: Uncomplicated stress incontinence. The patient has a positive cough stress test, and most urinary incontinence episodes she recorded are stress type. Urinalysis and PVR are normal, with no evidence of pelvic organ prolapse on exam.

Well-timed pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises have been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of both stress and urge incontinence when they’re done regularly, starting with 4 times a day and increased slowly to 8 times twice a day.9 Review Kegel technique and advise the patient to perform this maneuver and hold the contraction, if possible, whenever she is about to cough, laugh, sneeze, or otherwise exert herself. Tell her to practice Kegel exercises until they become second nature. If she continues to have trouble, she may need a referral to pelvic floor physical therapy to learn to do them effectively. (You can go to http://www.apta.org/apta/findapt/index.aspx?navID=10737422525 to find a therapist specializing in women’s health in your area.)

Dx: Uncomplicated urge incontinence. The patient has a normal cough stress test and most of her urinary incontinence episodes are the urge type. Her pelvic exam and PVR are within normal limits.

Prescribe an anticholinergic bladder agent. Medication with antimuscarinic properties has been shown to decrease urge incontinence and significantly improve patient-reported measures of quality of life.10

A reasonable approach is to start her on an inexpensive generic medication ( TABLE )11,12 and follow up in one month. If the medication helps and does not cause adverse effects, she can be maintained on it; if it’s effective but she has significant adverse effects (eg, constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, as well as confusion and sedation in the elderly), the patient can be switched to a more expensive brand-name drug with fewer adverse effects.

Behavioral training, including timed voiding and Kegel exercises, has been shown to significantly decrease symptoms of urge incontinence.9 Timed voiding can be especially helpful for nocturnal urge incontinence; advise the patient to set an alarm for an hour before the usual time she awakens with a sense of urgency, and to empty her bladder before it is so full that she leaks.

Point out, too, that not every urinary urge requires immediately running to the toilet. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that patients who were taught to respond to visual cues, such as a toilet, by walking past it, then sitting down, relaxing, and contracting their pelvic muscles repeatedly had diminished urgency. Their actions also inhibited detrusor contractions, and often prevented urine loss. When the training was combined with one or 2 lessons in proper Kegel technique—reinforced at several visits—weekly incontinence episodes were reduced by 80%. The controls, who had the same number of clinic visits but did not receive specific education on urgency-reduction strategies, reduced incontinence episodes by 40%.13

Dx: Fluid overuse. The patient is drinking an excessive quantity of fluid, as evidenced by urine volume >2100 cc. (The International Continence Society defines polyuria as >40 mL/kg per day.14 )

Advise the patient to decrease her overall fluid intake, particularly within several hours of bedtime. Studies of tea and coffee consumption and incontinence have had conflicting results,15,16 and data on caffeinated soda consumption and incontinence are lacking. Nonetheless, patients should be advised that there is a possible association between caffeinated beverages and urinary incontinence. (In one small study, caffeine was found to cause a significant increase in detrusor pressure.17 ) Giving women one-time general instructions on fluid intake modification has been shown to significantly decrease incontinence episodes.18

Dx: Badly timed medication intake. This patient is taking one or more drugs that may contribute to incontinence, such as alpha-blockers or diuretics, either shortly before going to bed or before activities that make a bathroom visit inconvenient or impossible.

Adjust her medication regimen to minimize nocturia or urinary urgency during times of peak activity—eg, taking a diuretic early in the day instead of in the afternoon or evening, if possible. Keep in mind, however, that this strategy is based primarily on expert opinion, as very little evidence exists to show that medication of any type has a significant effect on urinary continence.19

Dx: Lower extremity edema with postural diuresis. The patient has nocturia, with larger total urine output at night than during the day. She may or may not have some leakage.

Women with lower extremity edema due to a variety of medical causes often experience postural diuresis overnight. If the patient is already on a diuretic, the problem can often be ameliorated by taking it early in the day instead of in the afternoon or evening; if she’s not, prescribe a small dose of a diuretic, to be taken in the morning. This therapeutic intervention has not been rigorously studied, but is relatively easy to implement and worth a try for patients with heart failure or other causes of pedal edema.

Dx: Constipation associated with autonomic dysfunction. Because the rectum and bladder are controlled by the same sacral segments of the spinal cord and share many autonomic ganglia, problems in one compartment often affect another. In a patient for whom incontinence is a minor, or occasional, problem while constipation is a major complaint, the optimal approach is to treat the constipation first and see if the urinary incontinence also resolves.

A trial of polyethylene glycol is a good place to start, particularly if there is no evidence of another correctable cause of the incontinence. Studies have shown that successful treatment of constipation often results in significant improvement of urinary urgency and frequency.20

TABLE

Anticholinergic medications for urge incontinence11,12

| Medication | Dosing | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Oxybutynin | 2.5-5 mg bid to tid (≤5 mg qid) | Significant adverse effects, including constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention; confusion and sedation, particularly in elderly |

| Oxybutynin ER | 5-10 mg/d; increase weekly by 5-mg/d increments to ≤30 mg/d | |

| Oxybutynin transdermal patch (Oxytrol) | 1 patch 2x/wk on abdomen, hips, or buttocks (dose=3.9 mg/d) | Adverse effects may be less frequent than with oral medication due to the avoidance of metabolites |

| Oxybutynin transdermal gel (Gelnique) | 1 gel pack/d on abdomen, thighs, or shoulders (dose=100 mg in 1-g gel pack) | |

| Tolterodine (Detrol) | 1-2 mg bid (immediate release) or 2-4 mg/d (ER) | Similar effects and efficacy as oxybutynin, but adverse effects are decreased due to greater uroselectivity on muscarinic receptors |

| Darifenacin hydrobromide (Enablex) | 7.5 mg/d; increase to 15 mg/d after 2 wk if necessary | |

| Solifenacin (VESIcare) | 5-10 mg/d | |

| Fesoteridine (Toviaz) | 4-8 mg/d | |

| Trospium (Sanctura) | 20 mg bid (immediate release) or 60 mg/d (ER) | |

| ER, extended release. | ||

These conditions typically warrant a referral

Dx: Hematuria. Urinalysis with hematuria but no evidence of a urinary tract infection should raise a red flag, regardless of other findings. The patient should be referred for further urologic evaluation, including cystoscopy, although you may want to repeat the urinalysis with another clean-catch specimen first. Straight catheterization is not recommended in such a case, as a traumatized urethra can be a source of hematuria.

Dx: Stress incontinence with an anatomic abnormality. There are 2 options for a patient who has stress incontinence with an obvious cystocele on exam: Fit her with a pessary (or refer her to a physician who has this capability), or provide a referral to a urogynecologist for corrective surgery. Which option to choose should be a collaborative decision between patient and physician. For most women, it makes sense to try the pessary first.

Dx: Urinary retention. A patient with a high normal or elevated PVR (>100-200 cc) and no obvious pelvic organ prolapse needs a work-up for urinary retention. There is a broad differential that can be divided into neurologic, obstructive, and pharmacologic etiologies.21 A referral is indicated so that a urologist can oversee the work-up.

Particularly worrisome causes of urinary retention are multiple sclerosis, which is more likely in a relatively young, otherwise healthy woman, and a pelvic mass. Medications are also a likely cause. The list of drugs that can induce urinary retention is extensive, and includes anticholinergics, antidepressants (tricyclics and some heterocyclics), antihistamines, and muscle relaxants, among others. If you’re unable to find a likely cause, a referral is indicated so that a urologist can oversee the work-up.

CORRESPONDENCE Abigail Lowther, MD, University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine, 24 Frank Lloyd Wright Drive, Lobby H, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-5795; abigaill@med.umich.edu

1. Hunskaar S, Lose G, Sykes D, et al. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int 2004;93:324-330.

2. Roberts RO, Jacobsen SJ, Rhodes T, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community-based cohort: prevalence and healthcare-seeking. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:467-472.

3. Markland AD, Richter HE, Chyng-Wen F, et al. Prevalence and trends of urinary incontinence in adults in the United States, 2001-2008. J Urol 2011;186:589-593.

4. Kinchen KS, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. Factors associated with women’s decisions to seek treatment for urinary incontinence. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:687-698.

5. O’Donnell M, Viktrup L, Hunskaar S. The role of general practitioners in the initial management of women with urinary incontinence in France, Germany, Spain and the UK. Eur J Gen Pract 2007;13:20-26.

6. Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle PG, et al. A practice-based intervention to improve primary care for falls, urinary incontinence, and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:547-555.

7. Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, Carchidi LT, et al. On the lack of correlation between self-report and urine loss measured with standing provocation test in older stress-incontinent women. J Womens Health 1999;8:157-162.

8. Deng DY. Urinary incontinence in women. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:101-109.

9. Nygaard IE, Kreder KJ, Lepic MM, et al. Efficacy of pelvic floor muscle exercises in women with stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:120-125.

10. Van Kerrebroeck PE, Kelleher CJ, Coyne KS, et al. Correlations among improvements in urgency urinary incontinence, health-related quality of life, and perception of bladder-related problems in incontinent subjects with overactive bladder treated with tolterodine or placebo. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:13-18.

11. Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Burgio KL, et al. Urinary incontinence in older adults. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:558-570.

12. Davila GW, Starkman JS, Dmochowski RR. Transdermal oxybutynin for overactive bladder. Urol Clin North Am 2006;33:455-463.

13. Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1995-2000.

14. Homma Y. Lower urinary tract symptomatology: its definition and confusion. J Urol 2008;15:35-43.

15. Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, et al. Are smoking and other lifestyle factors associated with female urinary incontinence? The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. BJOG. 2003;110:247-254.

16. Hirayama F, Lee AH. Green tea drinking is inversely associated with urinary incontinence in middle-aged and older women. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30:1262-1265.

17. Creighton SM, Stanton SL. Caffeine: does it affect your bladder? Br J Urol 1990;66:613-614

18. Zimmern P, Litman HJ, Mueller E, et al. Effect of fluid management on fluid intake and urge incontinence in a trial for overactive bladder in women. BJU Int. 2010;105:1680-1685.

19. Tsakiris P, Oelke M, Michel MC. Drug-induced urinary incontinence. Drugs Aging 2008;25:541-549.

20. Wyman JF, Burgio KL, Newman DK. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:1177-1191.

21. Selius B, Subedi R. Urinary retention in adults: diagnosis and initial management. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:643-650.

1. Hunskaar S, Lose G, Sykes D, et al. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int 2004;93:324-330.

2. Roberts RO, Jacobsen SJ, Rhodes T, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community-based cohort: prevalence and healthcare-seeking. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:467-472.

3. Markland AD, Richter HE, Chyng-Wen F, et al. Prevalence and trends of urinary incontinence in adults in the United States, 2001-2008. J Urol 2011;186:589-593.

4. Kinchen KS, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. Factors associated with women’s decisions to seek treatment for urinary incontinence. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:687-698.

5. O’Donnell M, Viktrup L, Hunskaar S. The role of general practitioners in the initial management of women with urinary incontinence in France, Germany, Spain and the UK. Eur J Gen Pract 2007;13:20-26.

6. Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle PG, et al. A practice-based intervention to improve primary care for falls, urinary incontinence, and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:547-555.

7. Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, Carchidi LT, et al. On the lack of correlation between self-report and urine loss measured with standing provocation test in older stress-incontinent women. J Womens Health 1999;8:157-162.

8. Deng DY. Urinary incontinence in women. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:101-109.

9. Nygaard IE, Kreder KJ, Lepic MM, et al. Efficacy of pelvic floor muscle exercises in women with stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:120-125.

10. Van Kerrebroeck PE, Kelleher CJ, Coyne KS, et al. Correlations among improvements in urgency urinary incontinence, health-related quality of life, and perception of bladder-related problems in incontinent subjects with overactive bladder treated with tolterodine or placebo. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:13-18.

11. Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Burgio KL, et al. Urinary incontinence in older adults. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:558-570.

12. Davila GW, Starkman JS, Dmochowski RR. Transdermal oxybutynin for overactive bladder. Urol Clin North Am 2006;33:455-463.

13. Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1995-2000.

14. Homma Y. Lower urinary tract symptomatology: its definition and confusion. J Urol 2008;15:35-43.

15. Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, et al. Are smoking and other lifestyle factors associated with female urinary incontinence? The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. BJOG. 2003;110:247-254.

16. Hirayama F, Lee AH. Green tea drinking is inversely associated with urinary incontinence in middle-aged and older women. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30:1262-1265.

17. Creighton SM, Stanton SL. Caffeine: does it affect your bladder? Br J Urol 1990;66:613-614

18. Zimmern P, Litman HJ, Mueller E, et al. Effect of fluid management on fluid intake and urge incontinence in a trial for overactive bladder in women. BJU Int. 2010;105:1680-1685.

19. Tsakiris P, Oelke M, Michel MC. Drug-induced urinary incontinence. Drugs Aging 2008;25:541-549.

20. Wyman JF, Burgio KL, Newman DK. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:1177-1191.

21. Selius B, Subedi R. Urinary retention in adults: diagnosis and initial management. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:643-650.