User login

Promoting Quality Asthma Care in Hospital Emergency Departments: Past, Present, and Future Efforts in Florida

From the Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe efforts to assess, improve, and reinforce asthma management protocols and practices at hospital emergency departments (EDs) in Florida.

- Methods: Description of 4 stages of an evaluation and outreach effort including assessment of current ED asthma care protocols and quality improvement plans; interactive education about asthma management best practices for hospital ED professionals; home visiting asthma management pilot programs for community members; and collaborative learning opportunities for clinicians and health care administrators.

- Results: We describe the evidence basis for each component of the Florida Asthma Program’s strategy, review key lessons learned, and discuss next steps.

- Conclusion: Promoting comprehensive, integrative asthma care within and beyond EDs will remain a top priority for the Florida Asthma Program. Our interdisciplinary team continues to explore additional strategies for creating transformational change in the quality and utilization of emergency care for Floridians of all ages who live with asthma.

Approximately 10% of children and 8% of adults in Florida live with asthma, a costly disease whose care expenses total over $56 billion in the United States each year [1]. Asthma prevalence and care costs continue to rise in Florida and other states [1], and 1.8 million asthma-related emergency department visits occur each year [2]. In 2010, a total of 90,770 emergency department visits occurred in Florida with asthma listed as the primary diagnosis, an increase of 12.7% from 2005 [1]. National standards for asthma care in the emergency department have been developed [3] and improving the quality of emergency department asthma care is a focus for many health care organizations.

In 2012, the Florida Asthma Program partnered with the Florida Hospital Association to review current asthma care activities and policies in emergency departments statewide. Evaluators from Florida State University developed and implemented a survey to assess gaps in emergency department asthma management at Florida hospitals. The survey illuminated strengths and weaknesses in the processes and resources used by hospital emergency departments in responding to asthma symptoms, and 3 follow-up interventions emerged from this assessment effort. In this paper, I discuss our survey findings and follow-up activities.

Assessment of ED Management Practices

The survey instrument had both open- and closed-ended questions and took about 15 minutes to complete. Participants were advised that publicly available document would not identify individuals or hospitals by name and they would receive the final summary report.

Our results suggest inconsistency among sampled Florida hospitals’ adherence to national standards for treatment of asthma in emergency departments. Several hospitals were refining their emergency care protocols to incorporate guideline recommendations. Despite a lack of formal emergency department protocols in some hospitals, adherence to national guidelines for emergency care was robust for patient education and medication prescribing, but weaker for formal care planning and medical follow-up.

Each of our participating hospitals reported using an evidence-based approach that incorporated national asthma care guidelines. However, operationalization and documentation of guidelines-based care varied dramatically across participating hospitals. Some hospitals already had well-developed protocols for emergency department asthma care, including both detailed clinical pathways and more holistic approaches incorporating foundational elements of guidelines-based care. By contrast, others had no formal documentation of their asthma management practices for patients seen in the emergency department.

By contrast, we found that utilization of evidence-based supportive services was uniformly high. Specific emergency department asthma care services that appeared to be well developed in Florida were case management, community engagement, and asthma education by certified professionals. We also found that many of the hospitals were in the process of reviewing and documenting their emergency department asthma care practices at the time of our study. Participants noted particular challenges with creating written care plans and dispensing inhaled medications for home use. Following up on the latter issue revealed that Florida state policy on medication use and dispensation in emergency department setting were the main barrier to sending patients with asthma home from the emergency department with needed medications. Consequently, the Florida Asthma Program worked with the state board of pharmacy to implement reforms, which became effective February 2014 [6].

Educational Webinars

Research indicates that quality improvement interventions can improve the outcomes and processes of care for children with asthma [7]. We noted that respondents were often unaware of how other hospitals in the state compared to their own on both national quality measures and strategies for continuous quality improvement. Therefore, promoting dialogue and collaboration became a priority. We developed 2 webinars to allow hospital personnel to learn directly from each other about ways to improve emergency department asthma care. The webinars were open to personnel from any hospital in Florida that wished to attend, not just the hospitals that participated in the initial study.

Florida Asthma Coalition members with clinical expertise partnered with Florida Hospital Association employees and asthma program staff from the Department of Health to design the webinars. Presentations were invited from hospitals that had successfully incorporated EPR-3 guidance into all aspects of their emergency department asthma care and any associated follow-up services. We asked presenters to focus on how their hospitals overcame challenges to successful guideline implementation. During each interactive session, participants had the opportunity to ask questions and receive guidance from presenters and presenters also encouraged hospitals to develop their own internal training webinars and supportive resources for learning, and to share the interventions and materials they created with one another as well as relevant professional organizations.

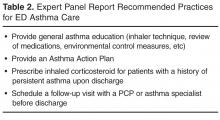

The webinars were two complementary 90-minute sessions and were delivered in summer 2013. The first webinar, “Optimal Asthma Treatment in the Emergency Department,” focused specifically on best practices for care in emergency departments themselves. It covered EPR-3 recommended activities such as helping families create Asthma Action Plans and demonstrating proper inhaler technique. The second webinar, “Transitioning Asthma Care from the Emergency Department to Prevent Repeat Visits,” focused on strategies for preventing repeat visits with people who have been seen in the emergency department for asthma. It covered activities like creating linkages with primary and specialty care providers skilled in asthma care, and partnering with case management professionals to follow discharged patients over time. Both webinars emphasized strategies for consistently implementing and sustaining adherence to EPR-3 guidelines in emergency departments. Participants attended sessions from their offices or meeting rooms by logging onto the webinar in a browser window and dialing into the conference line. Full recordings of both sessions remain available online at http://floridaasthmacoalition.com/healthcare-providers/recorded-webinars/.

We evaluated the reach and effectiveness of the webinars [8]. Attendance was high, with 137 pre-registrants and many more participating. Over 90% of participants in each session rated the content and discussion as either very good or excellent, and at least 90% indicated that they would recommend the learning modules to their colleagues. Participants expressed strong interest in continuing the activities initiated with the web sessions on a year-round basis, with particular emphasis on partnership building, continuing education, and cooperative action.

Asthma-Friendly Homes Program

Data from our preliminary assessment of asthma management practices in Florida hospitals suggested that an important priority for improving emergency department asthma care is reducing repeat visits. Rates of repeated emergency department utilization for asthma management correlate inversely with both household income and quality of available resources for home self-management. Our team considered developing a home visiting program to bring asthma education programming and self-management tools to children and their families. Rather than trying to build a new program ourselves, we extended our focus on strategic partnership to the Florida department of health’s regional affiliate in Miami-Dade County, who were developing a home visiting intervention to reduce emergency department visits and improve continuity of care for children with asthma [9].

Early planning for the Miami-Dade program included a focus on low-income communities and households, including the homes of children with Latino and/or Haitian heritage. The Asthma-Friendly Homes Program was developed in partnership with Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, with the hospital and the local Department of Health affiliate sharing responsibility for program implementation and management as well as data collection [10]. Small adjustments were made to the overall program strategy as partner agencies began working with Florida Asthma Program managers and evaluators. Now in its second year of implementation, the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program continues to evolve and grow.

Preventing repeat visits to the emergency room in favor of daily self-management at home remains the central emphasis of the program. Its curriculum focuses on empowering children with asthma and their families to self-manage effectively and consistently. By consequence, the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program encourages patients to use emergency department care services only when indicated by signs and symptoms rather than as a primary source of care. To achieve these objectives, the program uses a combination of activities including home visits and regular follow-up by case management.

Delivery of the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program begins with determination of eligibility via medical records review. Data analysts from the regional Miami-Dade branch of department of health collaborate with case managers from Nicklaus Children’s Hospital to identify children who are eligible for participation. Eligibility criteria include 3 or more visits to the emergency room for asthma within the past year, related care costs totaling at least $50,000 in the past year, and residency in 1 of 7 target zip codes that represent low-income communities. When a child is deemed eligible, case managers contact their family to facilitate scheduling of a home environmental assessment by trained specialists from the department of health. During this visit, families receive information about common asthma triggers within their homes, and talk with environmental assessors about possible mitigation strategies that are appropriate for their specific economic and instrumental resources. At the conclusion of this visit, families are asked if they would like to receive an educational intervention to help their child build self-management skills in a supportive environment.

Families that wish to participate in the educational component of Asthma-Friendly Homes are then put in touch with a certified asthma educator employed by Nicklaus Children’s Hospital. Participants can schedule a preliminary visit with their asthma educator themselves, or work with case management at Nicklaus to coordinate intake for the educational program. Visiting asthma educators begin by completing a preliminary demographics, symptoms, and skills assessment with family members. They deliver 3 sessions of education for participating children, each time assessing progress using a standardized questionnaire. Although the evaluation instruments for these sessions are standard, the curriculum used by asthma educators is tailored to the needs of each individual child and their family. The demographics, symptoms, and skills assessment is repeated with family members at the end of the third visit from asthma educators. Finally, case managers follow up with families after 6 months to assess retention of benefits from the program.

Participating children are also tracked in the hospital’s emergency department records to contextualize success with home-based self-management. Like data from the questionnaires, this information gets shared with Florida Asthma Program evaluators. Our team uses these data to understand the effectiveness of the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program itself, as well as its utility for preventing repeated utilization of hospital emergency department services. The program currently has 9 families participating, which is on target for the early stages of our pilot program with Miami. As we evaluate Asthma-Friendly Homes, we hope that this program will become a new standard in evidence-based best practices for keeping children out of the emergency room and healthy at home, both in Florida and across the nation. To disseminate results from this intervention in ways that promote adoption of effective self-management curricula by organizations working with vulnerable populations, we are thus focusing intensively on building networks that facilitate this sharing.

Learning and Action Networks

Building on lessons learned from our evaluation of emergency department asthma care and delivery of interactive webinars, our team proposed a systems-focused approach for implementing and sharing knowledge gained from these activities. As such, the department of health is developing Learning and Action Networks. LANs are mechanisms by which large-scale improvement around a given aim is fostered, studied, adapted, and rapidly spread. LANs are similar to “communities of practice” in that they promote learning among peer practitioners, but differ in that they focus on a specific improvement initiative, in this case delivery of and reimbursement for comprehensive asthma management.

The department of health has so far implemented 2 LANs, one for managed care organizations including those working under Medicaid and Florida KidCare, and one for providers, including federally qualified health centers, community health centers, and rural health centers. In future funding years, LANs will be established for pharmacists, hospitals, and public housing groups to promote coverage for and utilization of comprehensive asthma control services.

LANs are carried out in partnership with the professional organizations and related umbrella organizations serving each sector. A minimum of 3 webinars will be offered each year for each LAN. They will promote active engagement and communication between partners as well as offer opportunities to share successes and troubleshooting tips. Online forums or other means of communication will also be established based on the needs of participants. Topics will be driven by participant interests and will include performance and quality improvement, public health/health care system linkages, use of decision support tools, use of electronic health records for care coordination, and other issues related to the provision and reimbursement for evidence-based, comprehensive asthma control services.

LAN facilitators and members will learn continuously from one another. Members can implement best practices for strategic collaboration learned from facilitators, while facilitators will become familiar with best practices for asthma care that can be disseminated within and beyond Florida.

The LAN for hospitals will cover improving emergency department asthma care. This may include performance and quality improvement strategies, systems-level linkages between public health and clinical care, provider decision support tools, use of electronic health records for care coordination, case management resources for continuous follow-up after discharge, and evidence-based approaches to medication dispensing and monitoring.

Conclusion

Promoting comprehensive, integrative asthma care within and beyond emergency departments will remain a top priority for the Florida Asthma Program. Our interdisciplinary team of program managers and external evaluators continues to explore additional strategies for creating transformational change in the quality and utilization of emergency care for Floridians of all ages who live with asthma.

Acknowledgements: I thank Ms. Kim Streit and other members of the Florida Hospital Association for their outstanding assistance in conceptualizing and implementing this evaluation project. I thank Ms. Julie Dudley for developing content for the collaborative learning webinars described herein, as well as proposing and operationalizing Florida’s Learning and Action Networks for asthma care. I thank Ms. Jamie Forrest for facilitating delivery and evaluation of the hospital learning webinars. I thank Dr. Brittny Wells for helping to develop the Learning and Action Networks initiative in conjunction with other programs, and facilitating continued collaboration with hospitals. I thank Dr. Asit Sarkar for coordinating the Asthma Friendly Homes Program in Miami-Dade, and for helping to bring this program to other Florida communities. I thank Dr. Henry Carretta for his partnership in conducting the preliminary evaluation survey, and for his assistance with planning evaluation of hospital care quality improvement activities for the current project cycle.

Corresponding author: Alexandra C.H. Nowakowski, PhD, MPH, FSU College of Medicine, Regional Campus – Orlando,50 E. Colonial Drive, Suite 200, Orlando, FL 32801.

Funding/support: Evaluation of the Florida Asthma Program’s preliminary work with hospitals was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U59EH000523-03 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Current program development and evaluation efforts in this domain are supported by CDC Cooperative Agreement Number 2U59EH000523. Contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Forrest J, Dudley J. Burden of Asthma in Florida. Florida Department of Health, Division of Community Health Promotion, Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention, Florida Asthma Program. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.floridaasthmacoalition.org.

2. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency department summary tables. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011ed_web_tables.pdf.

3. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. NHLBI website. 2007. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthgdln.pdf.

4. Florida Hospital Association. Facts & Stats. FHA website. 2012. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.fha.org/reports-and-resources/facts-and-stats.aspx.

5. Nowakowski AC, Carretta HJ, Dudley JK, et al. Evaluating emergency department asthma management practices in Florida hospitals. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22:E8–E13.

6. State of Florida. The 2015 Florida Statutes, Chapter 465 – Pharmacy. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0400-0499/

0465/0465.html.

7. Bravata DM, Gienger AL, Holty JE, et al. Quality improvement strategies for children with asthma: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:572–81.

8. Nowakowski ACH, Carretta HJ, Smith TR, et al. Improving asthma management in hospital emergency departments with interactive webinars. Florida Public Health Rev 2015;12:31–3.

9. Moore E. Introduction to the asthma home-visit collaborative project. Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County EPI monthly report 2015;16(8).

10. Florida Asthma Coalition. Asthma-Friendly Homes Project. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.floridaasthmacoalition.com/healthcare-providers/asthma-friendly-home-project/.

From the Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe efforts to assess, improve, and reinforce asthma management protocols and practices at hospital emergency departments (EDs) in Florida.

- Methods: Description of 4 stages of an evaluation and outreach effort including assessment of current ED asthma care protocols and quality improvement plans; interactive education about asthma management best practices for hospital ED professionals; home visiting asthma management pilot programs for community members; and collaborative learning opportunities for clinicians and health care administrators.

- Results: We describe the evidence basis for each component of the Florida Asthma Program’s strategy, review key lessons learned, and discuss next steps.

- Conclusion: Promoting comprehensive, integrative asthma care within and beyond EDs will remain a top priority for the Florida Asthma Program. Our interdisciplinary team continues to explore additional strategies for creating transformational change in the quality and utilization of emergency care for Floridians of all ages who live with asthma.

Approximately 10% of children and 8% of adults in Florida live with asthma, a costly disease whose care expenses total over $56 billion in the United States each year [1]. Asthma prevalence and care costs continue to rise in Florida and other states [1], and 1.8 million asthma-related emergency department visits occur each year [2]. In 2010, a total of 90,770 emergency department visits occurred in Florida with asthma listed as the primary diagnosis, an increase of 12.7% from 2005 [1]. National standards for asthma care in the emergency department have been developed [3] and improving the quality of emergency department asthma care is a focus for many health care organizations.

In 2012, the Florida Asthma Program partnered with the Florida Hospital Association to review current asthma care activities and policies in emergency departments statewide. Evaluators from Florida State University developed and implemented a survey to assess gaps in emergency department asthma management at Florida hospitals. The survey illuminated strengths and weaknesses in the processes and resources used by hospital emergency departments in responding to asthma symptoms, and 3 follow-up interventions emerged from this assessment effort. In this paper, I discuss our survey findings and follow-up activities.

Assessment of ED Management Practices

The survey instrument had both open- and closed-ended questions and took about 15 minutes to complete. Participants were advised that publicly available document would not identify individuals or hospitals by name and they would receive the final summary report.

Our results suggest inconsistency among sampled Florida hospitals’ adherence to national standards for treatment of asthma in emergency departments. Several hospitals were refining their emergency care protocols to incorporate guideline recommendations. Despite a lack of formal emergency department protocols in some hospitals, adherence to national guidelines for emergency care was robust for patient education and medication prescribing, but weaker for formal care planning and medical follow-up.

Each of our participating hospitals reported using an evidence-based approach that incorporated national asthma care guidelines. However, operationalization and documentation of guidelines-based care varied dramatically across participating hospitals. Some hospitals already had well-developed protocols for emergency department asthma care, including both detailed clinical pathways and more holistic approaches incorporating foundational elements of guidelines-based care. By contrast, others had no formal documentation of their asthma management practices for patients seen in the emergency department.

By contrast, we found that utilization of evidence-based supportive services was uniformly high. Specific emergency department asthma care services that appeared to be well developed in Florida were case management, community engagement, and asthma education by certified professionals. We also found that many of the hospitals were in the process of reviewing and documenting their emergency department asthma care practices at the time of our study. Participants noted particular challenges with creating written care plans and dispensing inhaled medications for home use. Following up on the latter issue revealed that Florida state policy on medication use and dispensation in emergency department setting were the main barrier to sending patients with asthma home from the emergency department with needed medications. Consequently, the Florida Asthma Program worked with the state board of pharmacy to implement reforms, which became effective February 2014 [6].

Educational Webinars

Research indicates that quality improvement interventions can improve the outcomes and processes of care for children with asthma [7]. We noted that respondents were often unaware of how other hospitals in the state compared to their own on both national quality measures and strategies for continuous quality improvement. Therefore, promoting dialogue and collaboration became a priority. We developed 2 webinars to allow hospital personnel to learn directly from each other about ways to improve emergency department asthma care. The webinars were open to personnel from any hospital in Florida that wished to attend, not just the hospitals that participated in the initial study.

Florida Asthma Coalition members with clinical expertise partnered with Florida Hospital Association employees and asthma program staff from the Department of Health to design the webinars. Presentations were invited from hospitals that had successfully incorporated EPR-3 guidance into all aspects of their emergency department asthma care and any associated follow-up services. We asked presenters to focus on how their hospitals overcame challenges to successful guideline implementation. During each interactive session, participants had the opportunity to ask questions and receive guidance from presenters and presenters also encouraged hospitals to develop their own internal training webinars and supportive resources for learning, and to share the interventions and materials they created with one another as well as relevant professional organizations.

The webinars were two complementary 90-minute sessions and were delivered in summer 2013. The first webinar, “Optimal Asthma Treatment in the Emergency Department,” focused specifically on best practices for care in emergency departments themselves. It covered EPR-3 recommended activities such as helping families create Asthma Action Plans and demonstrating proper inhaler technique. The second webinar, “Transitioning Asthma Care from the Emergency Department to Prevent Repeat Visits,” focused on strategies for preventing repeat visits with people who have been seen in the emergency department for asthma. It covered activities like creating linkages with primary and specialty care providers skilled in asthma care, and partnering with case management professionals to follow discharged patients over time. Both webinars emphasized strategies for consistently implementing and sustaining adherence to EPR-3 guidelines in emergency departments. Participants attended sessions from their offices or meeting rooms by logging onto the webinar in a browser window and dialing into the conference line. Full recordings of both sessions remain available online at http://floridaasthmacoalition.com/healthcare-providers/recorded-webinars/.

We evaluated the reach and effectiveness of the webinars [8]. Attendance was high, with 137 pre-registrants and many more participating. Over 90% of participants in each session rated the content and discussion as either very good or excellent, and at least 90% indicated that they would recommend the learning modules to their colleagues. Participants expressed strong interest in continuing the activities initiated with the web sessions on a year-round basis, with particular emphasis on partnership building, continuing education, and cooperative action.

Asthma-Friendly Homes Program

Data from our preliminary assessment of asthma management practices in Florida hospitals suggested that an important priority for improving emergency department asthma care is reducing repeat visits. Rates of repeated emergency department utilization for asthma management correlate inversely with both household income and quality of available resources for home self-management. Our team considered developing a home visiting program to bring asthma education programming and self-management tools to children and their families. Rather than trying to build a new program ourselves, we extended our focus on strategic partnership to the Florida department of health’s regional affiliate in Miami-Dade County, who were developing a home visiting intervention to reduce emergency department visits and improve continuity of care for children with asthma [9].

Early planning for the Miami-Dade program included a focus on low-income communities and households, including the homes of children with Latino and/or Haitian heritage. The Asthma-Friendly Homes Program was developed in partnership with Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, with the hospital and the local Department of Health affiliate sharing responsibility for program implementation and management as well as data collection [10]. Small adjustments were made to the overall program strategy as partner agencies began working with Florida Asthma Program managers and evaluators. Now in its second year of implementation, the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program continues to evolve and grow.

Preventing repeat visits to the emergency room in favor of daily self-management at home remains the central emphasis of the program. Its curriculum focuses on empowering children with asthma and their families to self-manage effectively and consistently. By consequence, the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program encourages patients to use emergency department care services only when indicated by signs and symptoms rather than as a primary source of care. To achieve these objectives, the program uses a combination of activities including home visits and regular follow-up by case management.

Delivery of the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program begins with determination of eligibility via medical records review. Data analysts from the regional Miami-Dade branch of department of health collaborate with case managers from Nicklaus Children’s Hospital to identify children who are eligible for participation. Eligibility criteria include 3 or more visits to the emergency room for asthma within the past year, related care costs totaling at least $50,000 in the past year, and residency in 1 of 7 target zip codes that represent low-income communities. When a child is deemed eligible, case managers contact their family to facilitate scheduling of a home environmental assessment by trained specialists from the department of health. During this visit, families receive information about common asthma triggers within their homes, and talk with environmental assessors about possible mitigation strategies that are appropriate for their specific economic and instrumental resources. At the conclusion of this visit, families are asked if they would like to receive an educational intervention to help their child build self-management skills in a supportive environment.

Families that wish to participate in the educational component of Asthma-Friendly Homes are then put in touch with a certified asthma educator employed by Nicklaus Children’s Hospital. Participants can schedule a preliminary visit with their asthma educator themselves, or work with case management at Nicklaus to coordinate intake for the educational program. Visiting asthma educators begin by completing a preliminary demographics, symptoms, and skills assessment with family members. They deliver 3 sessions of education for participating children, each time assessing progress using a standardized questionnaire. Although the evaluation instruments for these sessions are standard, the curriculum used by asthma educators is tailored to the needs of each individual child and their family. The demographics, symptoms, and skills assessment is repeated with family members at the end of the third visit from asthma educators. Finally, case managers follow up with families after 6 months to assess retention of benefits from the program.

Participating children are also tracked in the hospital’s emergency department records to contextualize success with home-based self-management. Like data from the questionnaires, this information gets shared with Florida Asthma Program evaluators. Our team uses these data to understand the effectiveness of the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program itself, as well as its utility for preventing repeated utilization of hospital emergency department services. The program currently has 9 families participating, which is on target for the early stages of our pilot program with Miami. As we evaluate Asthma-Friendly Homes, we hope that this program will become a new standard in evidence-based best practices for keeping children out of the emergency room and healthy at home, both in Florida and across the nation. To disseminate results from this intervention in ways that promote adoption of effective self-management curricula by organizations working with vulnerable populations, we are thus focusing intensively on building networks that facilitate this sharing.

Learning and Action Networks

Building on lessons learned from our evaluation of emergency department asthma care and delivery of interactive webinars, our team proposed a systems-focused approach for implementing and sharing knowledge gained from these activities. As such, the department of health is developing Learning and Action Networks. LANs are mechanisms by which large-scale improvement around a given aim is fostered, studied, adapted, and rapidly spread. LANs are similar to “communities of practice” in that they promote learning among peer practitioners, but differ in that they focus on a specific improvement initiative, in this case delivery of and reimbursement for comprehensive asthma management.

The department of health has so far implemented 2 LANs, one for managed care organizations including those working under Medicaid and Florida KidCare, and one for providers, including federally qualified health centers, community health centers, and rural health centers. In future funding years, LANs will be established for pharmacists, hospitals, and public housing groups to promote coverage for and utilization of comprehensive asthma control services.

LANs are carried out in partnership with the professional organizations and related umbrella organizations serving each sector. A minimum of 3 webinars will be offered each year for each LAN. They will promote active engagement and communication between partners as well as offer opportunities to share successes and troubleshooting tips. Online forums or other means of communication will also be established based on the needs of participants. Topics will be driven by participant interests and will include performance and quality improvement, public health/health care system linkages, use of decision support tools, use of electronic health records for care coordination, and other issues related to the provision and reimbursement for evidence-based, comprehensive asthma control services.

LAN facilitators and members will learn continuously from one another. Members can implement best practices for strategic collaboration learned from facilitators, while facilitators will become familiar with best practices for asthma care that can be disseminated within and beyond Florida.

The LAN for hospitals will cover improving emergency department asthma care. This may include performance and quality improvement strategies, systems-level linkages between public health and clinical care, provider decision support tools, use of electronic health records for care coordination, case management resources for continuous follow-up after discharge, and evidence-based approaches to medication dispensing and monitoring.

Conclusion

Promoting comprehensive, integrative asthma care within and beyond emergency departments will remain a top priority for the Florida Asthma Program. Our interdisciplinary team of program managers and external evaluators continues to explore additional strategies for creating transformational change in the quality and utilization of emergency care for Floridians of all ages who live with asthma.

Acknowledgements: I thank Ms. Kim Streit and other members of the Florida Hospital Association for their outstanding assistance in conceptualizing and implementing this evaluation project. I thank Ms. Julie Dudley for developing content for the collaborative learning webinars described herein, as well as proposing and operationalizing Florida’s Learning and Action Networks for asthma care. I thank Ms. Jamie Forrest for facilitating delivery and evaluation of the hospital learning webinars. I thank Dr. Brittny Wells for helping to develop the Learning and Action Networks initiative in conjunction with other programs, and facilitating continued collaboration with hospitals. I thank Dr. Asit Sarkar for coordinating the Asthma Friendly Homes Program in Miami-Dade, and for helping to bring this program to other Florida communities. I thank Dr. Henry Carretta for his partnership in conducting the preliminary evaluation survey, and for his assistance with planning evaluation of hospital care quality improvement activities for the current project cycle.

Corresponding author: Alexandra C.H. Nowakowski, PhD, MPH, FSU College of Medicine, Regional Campus – Orlando,50 E. Colonial Drive, Suite 200, Orlando, FL 32801.

Funding/support: Evaluation of the Florida Asthma Program’s preliminary work with hospitals was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U59EH000523-03 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Current program development and evaluation efforts in this domain are supported by CDC Cooperative Agreement Number 2U59EH000523. Contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe efforts to assess, improve, and reinforce asthma management protocols and practices at hospital emergency departments (EDs) in Florida.

- Methods: Description of 4 stages of an evaluation and outreach effort including assessment of current ED asthma care protocols and quality improvement plans; interactive education about asthma management best practices for hospital ED professionals; home visiting asthma management pilot programs for community members; and collaborative learning opportunities for clinicians and health care administrators.

- Results: We describe the evidence basis for each component of the Florida Asthma Program’s strategy, review key lessons learned, and discuss next steps.

- Conclusion: Promoting comprehensive, integrative asthma care within and beyond EDs will remain a top priority for the Florida Asthma Program. Our interdisciplinary team continues to explore additional strategies for creating transformational change in the quality and utilization of emergency care for Floridians of all ages who live with asthma.

Approximately 10% of children and 8% of adults in Florida live with asthma, a costly disease whose care expenses total over $56 billion in the United States each year [1]. Asthma prevalence and care costs continue to rise in Florida and other states [1], and 1.8 million asthma-related emergency department visits occur each year [2]. In 2010, a total of 90,770 emergency department visits occurred in Florida with asthma listed as the primary diagnosis, an increase of 12.7% from 2005 [1]. National standards for asthma care in the emergency department have been developed [3] and improving the quality of emergency department asthma care is a focus for many health care organizations.

In 2012, the Florida Asthma Program partnered with the Florida Hospital Association to review current asthma care activities and policies in emergency departments statewide. Evaluators from Florida State University developed and implemented a survey to assess gaps in emergency department asthma management at Florida hospitals. The survey illuminated strengths and weaknesses in the processes and resources used by hospital emergency departments in responding to asthma symptoms, and 3 follow-up interventions emerged from this assessment effort. In this paper, I discuss our survey findings and follow-up activities.

Assessment of ED Management Practices

The survey instrument had both open- and closed-ended questions and took about 15 minutes to complete. Participants were advised that publicly available document would not identify individuals or hospitals by name and they would receive the final summary report.

Our results suggest inconsistency among sampled Florida hospitals’ adherence to national standards for treatment of asthma in emergency departments. Several hospitals were refining their emergency care protocols to incorporate guideline recommendations. Despite a lack of formal emergency department protocols in some hospitals, adherence to national guidelines for emergency care was robust for patient education and medication prescribing, but weaker for formal care planning and medical follow-up.

Each of our participating hospitals reported using an evidence-based approach that incorporated national asthma care guidelines. However, operationalization and documentation of guidelines-based care varied dramatically across participating hospitals. Some hospitals already had well-developed protocols for emergency department asthma care, including both detailed clinical pathways and more holistic approaches incorporating foundational elements of guidelines-based care. By contrast, others had no formal documentation of their asthma management practices for patients seen in the emergency department.

By contrast, we found that utilization of evidence-based supportive services was uniformly high. Specific emergency department asthma care services that appeared to be well developed in Florida were case management, community engagement, and asthma education by certified professionals. We also found that many of the hospitals were in the process of reviewing and documenting their emergency department asthma care practices at the time of our study. Participants noted particular challenges with creating written care plans and dispensing inhaled medications for home use. Following up on the latter issue revealed that Florida state policy on medication use and dispensation in emergency department setting were the main barrier to sending patients with asthma home from the emergency department with needed medications. Consequently, the Florida Asthma Program worked with the state board of pharmacy to implement reforms, which became effective February 2014 [6].

Educational Webinars

Research indicates that quality improvement interventions can improve the outcomes and processes of care for children with asthma [7]. We noted that respondents were often unaware of how other hospitals in the state compared to their own on both national quality measures and strategies for continuous quality improvement. Therefore, promoting dialogue and collaboration became a priority. We developed 2 webinars to allow hospital personnel to learn directly from each other about ways to improve emergency department asthma care. The webinars were open to personnel from any hospital in Florida that wished to attend, not just the hospitals that participated in the initial study.

Florida Asthma Coalition members with clinical expertise partnered with Florida Hospital Association employees and asthma program staff from the Department of Health to design the webinars. Presentations were invited from hospitals that had successfully incorporated EPR-3 guidance into all aspects of their emergency department asthma care and any associated follow-up services. We asked presenters to focus on how their hospitals overcame challenges to successful guideline implementation. During each interactive session, participants had the opportunity to ask questions and receive guidance from presenters and presenters also encouraged hospitals to develop their own internal training webinars and supportive resources for learning, and to share the interventions and materials they created with one another as well as relevant professional organizations.

The webinars were two complementary 90-minute sessions and were delivered in summer 2013. The first webinar, “Optimal Asthma Treatment in the Emergency Department,” focused specifically on best practices for care in emergency departments themselves. It covered EPR-3 recommended activities such as helping families create Asthma Action Plans and demonstrating proper inhaler technique. The second webinar, “Transitioning Asthma Care from the Emergency Department to Prevent Repeat Visits,” focused on strategies for preventing repeat visits with people who have been seen in the emergency department for asthma. It covered activities like creating linkages with primary and specialty care providers skilled in asthma care, and partnering with case management professionals to follow discharged patients over time. Both webinars emphasized strategies for consistently implementing and sustaining adherence to EPR-3 guidelines in emergency departments. Participants attended sessions from their offices or meeting rooms by logging onto the webinar in a browser window and dialing into the conference line. Full recordings of both sessions remain available online at http://floridaasthmacoalition.com/healthcare-providers/recorded-webinars/.

We evaluated the reach and effectiveness of the webinars [8]. Attendance was high, with 137 pre-registrants and many more participating. Over 90% of participants in each session rated the content and discussion as either very good or excellent, and at least 90% indicated that they would recommend the learning modules to their colleagues. Participants expressed strong interest in continuing the activities initiated with the web sessions on a year-round basis, with particular emphasis on partnership building, continuing education, and cooperative action.

Asthma-Friendly Homes Program

Data from our preliminary assessment of asthma management practices in Florida hospitals suggested that an important priority for improving emergency department asthma care is reducing repeat visits. Rates of repeated emergency department utilization for asthma management correlate inversely with both household income and quality of available resources for home self-management. Our team considered developing a home visiting program to bring asthma education programming and self-management tools to children and their families. Rather than trying to build a new program ourselves, we extended our focus on strategic partnership to the Florida department of health’s regional affiliate in Miami-Dade County, who were developing a home visiting intervention to reduce emergency department visits and improve continuity of care for children with asthma [9].

Early planning for the Miami-Dade program included a focus on low-income communities and households, including the homes of children with Latino and/or Haitian heritage. The Asthma-Friendly Homes Program was developed in partnership with Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, with the hospital and the local Department of Health affiliate sharing responsibility for program implementation and management as well as data collection [10]. Small adjustments were made to the overall program strategy as partner agencies began working with Florida Asthma Program managers and evaluators. Now in its second year of implementation, the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program continues to evolve and grow.

Preventing repeat visits to the emergency room in favor of daily self-management at home remains the central emphasis of the program. Its curriculum focuses on empowering children with asthma and their families to self-manage effectively and consistently. By consequence, the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program encourages patients to use emergency department care services only when indicated by signs and symptoms rather than as a primary source of care. To achieve these objectives, the program uses a combination of activities including home visits and regular follow-up by case management.

Delivery of the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program begins with determination of eligibility via medical records review. Data analysts from the regional Miami-Dade branch of department of health collaborate with case managers from Nicklaus Children’s Hospital to identify children who are eligible for participation. Eligibility criteria include 3 or more visits to the emergency room for asthma within the past year, related care costs totaling at least $50,000 in the past year, and residency in 1 of 7 target zip codes that represent low-income communities. When a child is deemed eligible, case managers contact their family to facilitate scheduling of a home environmental assessment by trained specialists from the department of health. During this visit, families receive information about common asthma triggers within their homes, and talk with environmental assessors about possible mitigation strategies that are appropriate for their specific economic and instrumental resources. At the conclusion of this visit, families are asked if they would like to receive an educational intervention to help their child build self-management skills in a supportive environment.

Families that wish to participate in the educational component of Asthma-Friendly Homes are then put in touch with a certified asthma educator employed by Nicklaus Children’s Hospital. Participants can schedule a preliminary visit with their asthma educator themselves, or work with case management at Nicklaus to coordinate intake for the educational program. Visiting asthma educators begin by completing a preliminary demographics, symptoms, and skills assessment with family members. They deliver 3 sessions of education for participating children, each time assessing progress using a standardized questionnaire. Although the evaluation instruments for these sessions are standard, the curriculum used by asthma educators is tailored to the needs of each individual child and their family. The demographics, symptoms, and skills assessment is repeated with family members at the end of the third visit from asthma educators. Finally, case managers follow up with families after 6 months to assess retention of benefits from the program.

Participating children are also tracked in the hospital’s emergency department records to contextualize success with home-based self-management. Like data from the questionnaires, this information gets shared with Florida Asthma Program evaluators. Our team uses these data to understand the effectiveness of the Asthma-Friendly Homes Program itself, as well as its utility for preventing repeated utilization of hospital emergency department services. The program currently has 9 families participating, which is on target for the early stages of our pilot program with Miami. As we evaluate Asthma-Friendly Homes, we hope that this program will become a new standard in evidence-based best practices for keeping children out of the emergency room and healthy at home, both in Florida and across the nation. To disseminate results from this intervention in ways that promote adoption of effective self-management curricula by organizations working with vulnerable populations, we are thus focusing intensively on building networks that facilitate this sharing.

Learning and Action Networks

Building on lessons learned from our evaluation of emergency department asthma care and delivery of interactive webinars, our team proposed a systems-focused approach for implementing and sharing knowledge gained from these activities. As such, the department of health is developing Learning and Action Networks. LANs are mechanisms by which large-scale improvement around a given aim is fostered, studied, adapted, and rapidly spread. LANs are similar to “communities of practice” in that they promote learning among peer practitioners, but differ in that they focus on a specific improvement initiative, in this case delivery of and reimbursement for comprehensive asthma management.

The department of health has so far implemented 2 LANs, one for managed care organizations including those working under Medicaid and Florida KidCare, and one for providers, including federally qualified health centers, community health centers, and rural health centers. In future funding years, LANs will be established for pharmacists, hospitals, and public housing groups to promote coverage for and utilization of comprehensive asthma control services.

LANs are carried out in partnership with the professional organizations and related umbrella organizations serving each sector. A minimum of 3 webinars will be offered each year for each LAN. They will promote active engagement and communication between partners as well as offer opportunities to share successes and troubleshooting tips. Online forums or other means of communication will also be established based on the needs of participants. Topics will be driven by participant interests and will include performance and quality improvement, public health/health care system linkages, use of decision support tools, use of electronic health records for care coordination, and other issues related to the provision and reimbursement for evidence-based, comprehensive asthma control services.

LAN facilitators and members will learn continuously from one another. Members can implement best practices for strategic collaboration learned from facilitators, while facilitators will become familiar with best practices for asthma care that can be disseminated within and beyond Florida.

The LAN for hospitals will cover improving emergency department asthma care. This may include performance and quality improvement strategies, systems-level linkages between public health and clinical care, provider decision support tools, use of electronic health records for care coordination, case management resources for continuous follow-up after discharge, and evidence-based approaches to medication dispensing and monitoring.

Conclusion

Promoting comprehensive, integrative asthma care within and beyond emergency departments will remain a top priority for the Florida Asthma Program. Our interdisciplinary team of program managers and external evaluators continues to explore additional strategies for creating transformational change in the quality and utilization of emergency care for Floridians of all ages who live with asthma.

Acknowledgements: I thank Ms. Kim Streit and other members of the Florida Hospital Association for their outstanding assistance in conceptualizing and implementing this evaluation project. I thank Ms. Julie Dudley for developing content for the collaborative learning webinars described herein, as well as proposing and operationalizing Florida’s Learning and Action Networks for asthma care. I thank Ms. Jamie Forrest for facilitating delivery and evaluation of the hospital learning webinars. I thank Dr. Brittny Wells for helping to develop the Learning and Action Networks initiative in conjunction with other programs, and facilitating continued collaboration with hospitals. I thank Dr. Asit Sarkar for coordinating the Asthma Friendly Homes Program in Miami-Dade, and for helping to bring this program to other Florida communities. I thank Dr. Henry Carretta for his partnership in conducting the preliminary evaluation survey, and for his assistance with planning evaluation of hospital care quality improvement activities for the current project cycle.

Corresponding author: Alexandra C.H. Nowakowski, PhD, MPH, FSU College of Medicine, Regional Campus – Orlando,50 E. Colonial Drive, Suite 200, Orlando, FL 32801.

Funding/support: Evaluation of the Florida Asthma Program’s preliminary work with hospitals was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U59EH000523-03 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Current program development and evaluation efforts in this domain are supported by CDC Cooperative Agreement Number 2U59EH000523. Contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Forrest J, Dudley J. Burden of Asthma in Florida. Florida Department of Health, Division of Community Health Promotion, Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention, Florida Asthma Program. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.floridaasthmacoalition.org.

2. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency department summary tables. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011ed_web_tables.pdf.

3. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. NHLBI website. 2007. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthgdln.pdf.

4. Florida Hospital Association. Facts & Stats. FHA website. 2012. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.fha.org/reports-and-resources/facts-and-stats.aspx.

5. Nowakowski AC, Carretta HJ, Dudley JK, et al. Evaluating emergency department asthma management practices in Florida hospitals. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22:E8–E13.

6. State of Florida. The 2015 Florida Statutes, Chapter 465 – Pharmacy. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0400-0499/

0465/0465.html.

7. Bravata DM, Gienger AL, Holty JE, et al. Quality improvement strategies for children with asthma: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:572–81.

8. Nowakowski ACH, Carretta HJ, Smith TR, et al. Improving asthma management in hospital emergency departments with interactive webinars. Florida Public Health Rev 2015;12:31–3.

9. Moore E. Introduction to the asthma home-visit collaborative project. Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County EPI monthly report 2015;16(8).

10. Florida Asthma Coalition. Asthma-Friendly Homes Project. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.floridaasthmacoalition.com/healthcare-providers/asthma-friendly-home-project/.

1. Forrest J, Dudley J. Burden of Asthma in Florida. Florida Department of Health, Division of Community Health Promotion, Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention, Florida Asthma Program. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.floridaasthmacoalition.org.

2. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency department summary tables. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011ed_web_tables.pdf.

3. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. NHLBI website. 2007. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthgdln.pdf.

4. Florida Hospital Association. Facts & Stats. FHA website. 2012. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.fha.org/reports-and-resources/facts-and-stats.aspx.

5. Nowakowski AC, Carretta HJ, Dudley JK, et al. Evaluating emergency department asthma management practices in Florida hospitals. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22:E8–E13.

6. State of Florida. The 2015 Florida Statutes, Chapter 465 – Pharmacy. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0400-0499/

0465/0465.html.

7. Bravata DM, Gienger AL, Holty JE, et al. Quality improvement strategies for children with asthma: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:572–81.

8. Nowakowski ACH, Carretta HJ, Smith TR, et al. Improving asthma management in hospital emergency departments with interactive webinars. Florida Public Health Rev 2015;12:31–3.

9. Moore E. Introduction to the asthma home-visit collaborative project. Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County EPI monthly report 2015;16(8).

10. Florida Asthma Coalition. Asthma-Friendly Homes Project. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 at www.floridaasthmacoalition.com/healthcare-providers/asthma-friendly-home-project/.