User login

I’ll make a note of that

I’ve worked hard to get rid of paper, or at least minimize it.

I use e-fax for sending and receiving as much as possible. I send scripts and order digitally when I can.

But, 23 years into a paperless practice, the stuff isn’t going away soon. Nor I do I want it to.

For many applications paper is just easier (at least to me) to use. When I have a meeting and know I’ll need to read from notes, I’d much rather have them on paper than a screen, so I print them up. Even a grocery list is easier to scribble down on something and look at as I wander the aisles, rather than navigate to an app every 2 minutes. Paper isn’t susceptible to the whims of battery power, signal strength, being dropped, or software glitches.

I’m also not particularly good at taking notes on a computer. I’m sure most of the current generation of physicians is (or they just use a scribe), but I’m old school. Since day one I’ve had a note pad on my desk, jotting points and observations down on the fly (I use a pencil, too, if anyone remembers what that is). Then, when I have time, I type up my notes from the paper.

I also still have patients who, for whatever reason, want a handwritten prescription. Or sometimes need the legendary “doctor’s note” for work or school. Or need me to fill out forms.

Having grown up with paper, and been through school and residency with paper, it’s not easy to give it up entirely. There’s something reassuring about the tactile nature of flipping pages as opposed to scrolling up and down.

I’m not complaining about its decreased use, though. A digital world is, for the most part, much, much easier. Even now paper is just a transient medium for me. It’s either going to be scanned or shredded (or scanned, then shredded) when I’m done. I don’t want the hassle of paper charts as my repository of information. Currently I have 23 years of charts sitting on a Mac-Mini, and accessible from wherever I am on Earth (as long as I have a decent signal). You definitely can’t do that with paper.

On a larger scale paper has other, more significant, drawbacks: deforestation, pollution, freshwater and petroleum usage, and others. I’m aware of this, use only scratch paper for my scribbles and lists, and buy recycled paper products as much as possible.

Certainly I wish we had less use of it. For one thing, I’d love to be rid of all the junk mail that comes to my house, which far outnumbers anything of importance. I always send it straight to recycling, but it would be far better if it had never been created in the first place.

Realistically, though, it’s still a key part of medical practice and everyday life. I don’t see that changing anytime soon, nor do I really want it to. I’ll leave it to a future generation of doctors to make that break.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve worked hard to get rid of paper, or at least minimize it.

I use e-fax for sending and receiving as much as possible. I send scripts and order digitally when I can.

But, 23 years into a paperless practice, the stuff isn’t going away soon. Nor I do I want it to.

For many applications paper is just easier (at least to me) to use. When I have a meeting and know I’ll need to read from notes, I’d much rather have them on paper than a screen, so I print them up. Even a grocery list is easier to scribble down on something and look at as I wander the aisles, rather than navigate to an app every 2 minutes. Paper isn’t susceptible to the whims of battery power, signal strength, being dropped, or software glitches.

I’m also not particularly good at taking notes on a computer. I’m sure most of the current generation of physicians is (or they just use a scribe), but I’m old school. Since day one I’ve had a note pad on my desk, jotting points and observations down on the fly (I use a pencil, too, if anyone remembers what that is). Then, when I have time, I type up my notes from the paper.

I also still have patients who, for whatever reason, want a handwritten prescription. Or sometimes need the legendary “doctor’s note” for work or school. Or need me to fill out forms.

Having grown up with paper, and been through school and residency with paper, it’s not easy to give it up entirely. There’s something reassuring about the tactile nature of flipping pages as opposed to scrolling up and down.

I’m not complaining about its decreased use, though. A digital world is, for the most part, much, much easier. Even now paper is just a transient medium for me. It’s either going to be scanned or shredded (or scanned, then shredded) when I’m done. I don’t want the hassle of paper charts as my repository of information. Currently I have 23 years of charts sitting on a Mac-Mini, and accessible from wherever I am on Earth (as long as I have a decent signal). You definitely can’t do that with paper.

On a larger scale paper has other, more significant, drawbacks: deforestation, pollution, freshwater and petroleum usage, and others. I’m aware of this, use only scratch paper for my scribbles and lists, and buy recycled paper products as much as possible.

Certainly I wish we had less use of it. For one thing, I’d love to be rid of all the junk mail that comes to my house, which far outnumbers anything of importance. I always send it straight to recycling, but it would be far better if it had never been created in the first place.

Realistically, though, it’s still a key part of medical practice and everyday life. I don’t see that changing anytime soon, nor do I really want it to. I’ll leave it to a future generation of doctors to make that break.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve worked hard to get rid of paper, or at least minimize it.

I use e-fax for sending and receiving as much as possible. I send scripts and order digitally when I can.

But, 23 years into a paperless practice, the stuff isn’t going away soon. Nor I do I want it to.

For many applications paper is just easier (at least to me) to use. When I have a meeting and know I’ll need to read from notes, I’d much rather have them on paper than a screen, so I print them up. Even a grocery list is easier to scribble down on something and look at as I wander the aisles, rather than navigate to an app every 2 minutes. Paper isn’t susceptible to the whims of battery power, signal strength, being dropped, or software glitches.

I’m also not particularly good at taking notes on a computer. I’m sure most of the current generation of physicians is (or they just use a scribe), but I’m old school. Since day one I’ve had a note pad on my desk, jotting points and observations down on the fly (I use a pencil, too, if anyone remembers what that is). Then, when I have time, I type up my notes from the paper.

I also still have patients who, for whatever reason, want a handwritten prescription. Or sometimes need the legendary “doctor’s note” for work or school. Or need me to fill out forms.

Having grown up with paper, and been through school and residency with paper, it’s not easy to give it up entirely. There’s something reassuring about the tactile nature of flipping pages as opposed to scrolling up and down.

I’m not complaining about its decreased use, though. A digital world is, for the most part, much, much easier. Even now paper is just a transient medium for me. It’s either going to be scanned or shredded (or scanned, then shredded) when I’m done. I don’t want the hassle of paper charts as my repository of information. Currently I have 23 years of charts sitting on a Mac-Mini, and accessible from wherever I am on Earth (as long as I have a decent signal). You definitely can’t do that with paper.

On a larger scale paper has other, more significant, drawbacks: deforestation, pollution, freshwater and petroleum usage, and others. I’m aware of this, use only scratch paper for my scribbles and lists, and buy recycled paper products as much as possible.

Certainly I wish we had less use of it. For one thing, I’d love to be rid of all the junk mail that comes to my house, which far outnumbers anything of importance. I always send it straight to recycling, but it would be far better if it had never been created in the first place.

Realistically, though, it’s still a key part of medical practice and everyday life. I don’t see that changing anytime soon, nor do I really want it to. I’ll leave it to a future generation of doctors to make that break.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Footprints

Early Monday morning was my usual start-the-week routine: Set up things at the office, update my computer, check the mail, review the week’s schedule.

I was rolling the phones when a text passed by on my screen that a friend had died.

He wasn’t a close friend, but still someone I liked and got along with on the occasional times we ran into each other. Good neurologist, all-around nice person. It was a shock. I’d just seen him a week ago when we crossed paths and briefly chatted about life, the universe, and everything, before going on with our days.

We’d trained together back in the mid-90s. He was 2 years younger than I. I was in my last year of residency when he started the program. I remember being at different gatherings back then with him and his wife, a few with his then-young son, too.

And now he’s gone.

Along with the grief, you think about your own mortality. What can I be doing to hang around longer? To be better? To enjoy whatever time that I have left?

Why a mensch like him?

These are questions we all face at different times. Questions that have no answers (or at least not easy ones). There’s a lot of “why” in the universe.

There are people out there whom you don’t see often, but still consider friends, and enjoy seeing when you encounter them. Sometimes you’re bound by a common interest, or background, or who knows what. You may not think of them much, but it’s somehow reassuring to know they’re out there. And upsetting when you suddenly realize they aren’t.

You feel awful for them and their families. You wish there was a reason, or that something, anything, good will come out of the loss. But right now you don’t see any.

Our time here is never long enough. We make the best of what we have and wish for a better tomorrow.

As Longfellow wrote, the best we can hope for is to leave “footprints on the sands of time.”

I’ll miss you, friend.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Early Monday morning was my usual start-the-week routine: Set up things at the office, update my computer, check the mail, review the week’s schedule.

I was rolling the phones when a text passed by on my screen that a friend had died.

He wasn’t a close friend, but still someone I liked and got along with on the occasional times we ran into each other. Good neurologist, all-around nice person. It was a shock. I’d just seen him a week ago when we crossed paths and briefly chatted about life, the universe, and everything, before going on with our days.

We’d trained together back in the mid-90s. He was 2 years younger than I. I was in my last year of residency when he started the program. I remember being at different gatherings back then with him and his wife, a few with his then-young son, too.

And now he’s gone.

Along with the grief, you think about your own mortality. What can I be doing to hang around longer? To be better? To enjoy whatever time that I have left?

Why a mensch like him?

These are questions we all face at different times. Questions that have no answers (or at least not easy ones). There’s a lot of “why” in the universe.

There are people out there whom you don’t see often, but still consider friends, and enjoy seeing when you encounter them. Sometimes you’re bound by a common interest, or background, or who knows what. You may not think of them much, but it’s somehow reassuring to know they’re out there. And upsetting when you suddenly realize they aren’t.

You feel awful for them and their families. You wish there was a reason, or that something, anything, good will come out of the loss. But right now you don’t see any.

Our time here is never long enough. We make the best of what we have and wish for a better tomorrow.

As Longfellow wrote, the best we can hope for is to leave “footprints on the sands of time.”

I’ll miss you, friend.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Early Monday morning was my usual start-the-week routine: Set up things at the office, update my computer, check the mail, review the week’s schedule.

I was rolling the phones when a text passed by on my screen that a friend had died.

He wasn’t a close friend, but still someone I liked and got along with on the occasional times we ran into each other. Good neurologist, all-around nice person. It was a shock. I’d just seen him a week ago when we crossed paths and briefly chatted about life, the universe, and everything, before going on with our days.

We’d trained together back in the mid-90s. He was 2 years younger than I. I was in my last year of residency when he started the program. I remember being at different gatherings back then with him and his wife, a few with his then-young son, too.

And now he’s gone.

Along with the grief, you think about your own mortality. What can I be doing to hang around longer? To be better? To enjoy whatever time that I have left?

Why a mensch like him?

These are questions we all face at different times. Questions that have no answers (or at least not easy ones). There’s a lot of “why” in the universe.

There are people out there whom you don’t see often, but still consider friends, and enjoy seeing when you encounter them. Sometimes you’re bound by a common interest, or background, or who knows what. You may not think of them much, but it’s somehow reassuring to know they’re out there. And upsetting when you suddenly realize they aren’t.

You feel awful for them and their families. You wish there was a reason, or that something, anything, good will come out of the loss. But right now you don’t see any.

Our time here is never long enough. We make the best of what we have and wish for a better tomorrow.

As Longfellow wrote, the best we can hope for is to leave “footprints on the sands of time.”

I’ll miss you, friend.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Hunt, gather, and turn on the Keurig

I’m a creature of habit. I suspect most of us are.

One can of Diet Coke on the drive to my office. Turn on the WiFi and air conditioning. Fire up the computer and unload my briefcase. Then do online refills, check the Astronomy Picture of the Day, look over the day’s schedule, turn on the Keurig, and make one cup of coffee. And so on.

I’m sure most of us have similar routines. Our brains are probably wired that way for survival, though the reasons aren’t the same anymore. Once it was get up, look outside the cave for predators, make sure the tribe is all accounted for, go to the stream for water, look for berries.

The fact is that automatic habits are critical for everything we do. Driving a car is really a series of repetitive tasks. Being able to put most of the ride on our brain’s autopilot allows us to move our attention to scanning the surroundings for changes, and to think about other items such as wonder what to do for dinner and if I remembered to turn off theWiFi and Keurig.

The practice of medicine is similar. Some things are internalized. Watching patients walk back to my office, looking at their hands as they fill out forms, hearing them introduce themselves, and other things that we subconsciously process as part of the exam before we’ve even officially begun the appointment. I quietly file such things away to be used later in the visit.

It certainly wasn’t always that way. In training we learn to filter out signal from noise, because the information available is huge. We all read tests of some sort. When I began reading EEGs, the images and lines were overwhelming, but with time and experience I became skilled at whittling down the mass of information into the things that really needed to be noted so I could turn pages faster (yes, youngsters, EEGs used to be on paper). Now, scanning the screen becomes a background habit, with the brain focusing more on things that stand out (or going back to thinking about what to do for dinner).

The brain in this way is the ultimate Swiss Army Knife – many tools available, but how we adapt and use them for our individual needs is variable.

Which is pretty impressive, actually. In the era of AI and computers, we each come with a (roughly) 2.5-petabyte hard drive that’s not only capable of storing all that information, but figuring out how to use it when we need to. The process is so smooth that we’re rarely aware of it. But what a marvel it is.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m a creature of habit. I suspect most of us are.

One can of Diet Coke on the drive to my office. Turn on the WiFi and air conditioning. Fire up the computer and unload my briefcase. Then do online refills, check the Astronomy Picture of the Day, look over the day’s schedule, turn on the Keurig, and make one cup of coffee. And so on.

I’m sure most of us have similar routines. Our brains are probably wired that way for survival, though the reasons aren’t the same anymore. Once it was get up, look outside the cave for predators, make sure the tribe is all accounted for, go to the stream for water, look for berries.

The fact is that automatic habits are critical for everything we do. Driving a car is really a series of repetitive tasks. Being able to put most of the ride on our brain’s autopilot allows us to move our attention to scanning the surroundings for changes, and to think about other items such as wonder what to do for dinner and if I remembered to turn off theWiFi and Keurig.

The practice of medicine is similar. Some things are internalized. Watching patients walk back to my office, looking at their hands as they fill out forms, hearing them introduce themselves, and other things that we subconsciously process as part of the exam before we’ve even officially begun the appointment. I quietly file such things away to be used later in the visit.

It certainly wasn’t always that way. In training we learn to filter out signal from noise, because the information available is huge. We all read tests of some sort. When I began reading EEGs, the images and lines were overwhelming, but with time and experience I became skilled at whittling down the mass of information into the things that really needed to be noted so I could turn pages faster (yes, youngsters, EEGs used to be on paper). Now, scanning the screen becomes a background habit, with the brain focusing more on things that stand out (or going back to thinking about what to do for dinner).

The brain in this way is the ultimate Swiss Army Knife – many tools available, but how we adapt and use them for our individual needs is variable.

Which is pretty impressive, actually. In the era of AI and computers, we each come with a (roughly) 2.5-petabyte hard drive that’s not only capable of storing all that information, but figuring out how to use it when we need to. The process is so smooth that we’re rarely aware of it. But what a marvel it is.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m a creature of habit. I suspect most of us are.

One can of Diet Coke on the drive to my office. Turn on the WiFi and air conditioning. Fire up the computer and unload my briefcase. Then do online refills, check the Astronomy Picture of the Day, look over the day’s schedule, turn on the Keurig, and make one cup of coffee. And so on.

I’m sure most of us have similar routines. Our brains are probably wired that way for survival, though the reasons aren’t the same anymore. Once it was get up, look outside the cave for predators, make sure the tribe is all accounted for, go to the stream for water, look for berries.

The fact is that automatic habits are critical for everything we do. Driving a car is really a series of repetitive tasks. Being able to put most of the ride on our brain’s autopilot allows us to move our attention to scanning the surroundings for changes, and to think about other items such as wonder what to do for dinner and if I remembered to turn off theWiFi and Keurig.

The practice of medicine is similar. Some things are internalized. Watching patients walk back to my office, looking at their hands as they fill out forms, hearing them introduce themselves, and other things that we subconsciously process as part of the exam before we’ve even officially begun the appointment. I quietly file such things away to be used later in the visit.

It certainly wasn’t always that way. In training we learn to filter out signal from noise, because the information available is huge. We all read tests of some sort. When I began reading EEGs, the images and lines were overwhelming, but with time and experience I became skilled at whittling down the mass of information into the things that really needed to be noted so I could turn pages faster (yes, youngsters, EEGs used to be on paper). Now, scanning the screen becomes a background habit, with the brain focusing more on things that stand out (or going back to thinking about what to do for dinner).

The brain in this way is the ultimate Swiss Army Knife – many tools available, but how we adapt and use them for our individual needs is variable.

Which is pretty impressive, actually. In the era of AI and computers, we each come with a (roughly) 2.5-petabyte hard drive that’s not only capable of storing all that information, but figuring out how to use it when we need to. The process is so smooth that we’re rarely aware of it. But what a marvel it is.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Dusty, but still cool

When I was 16, keeping my car shiny was a priority. I washed it every weekend and waxed it once a month. I was pretty good at it and got paid to do the occasional job for a neighbor, too.

In college I was busier, and my car was back at the house, so it didn’t need to be washed as much.

In medical school I think I washed the car once a year. Residency was probably the same.

Today I realized I couldn’t remember when I last had it washed (at my age I don’t have time to do it myself). So I looked it up in Quicken: Nov. 14, 2018.

Really? I’ve gone almost 5 years without washing my car? I can’t even blame that on the pandemic.

I mean, I still like my car. It’s comfortable, has good air conditioning (in Phoenix that’s critical), and gets me where I want to go. At my age those things are what’s really important. It’s hard to believe that 40 years ago, keeping a polished car was the center of my existence. Of course, it probably still is for most guys that age.

It’s a reminder of how much things change as life goes by.

Here in my little corner of neurology, multiple sclerosis has gone from steroids for relapses, to a few injections of mild benefit, to a bunch of drugs that are, literally, game-changing for many patients. And the Big Four epilepsy drugs (Dilantin, Tegretol, Depakote, and Phenobarb) are slowly fading into the background.

But back to changing priorities – it’s the way life rewrites our plans at each step. From a freshly waxed car to good grades to mortgages to kids – and then watching as they wax their cars.

Suddenly my car looks dusty. Am I the same way? I’m certainly not 16 anymore. Realistically, the majority of my life and career are behind me now. That doesn’t mean I’m not still having fun, it’s just the truth. I try not to think about it that much, as doing so won’t change anything.

In all honesty, neither did washing my car. I mean, the car looked good, but did it make me one of the cool kids? Or get me a girlfriend? Or invited to THE parties? Not at all. Like so many things about appearances, very few of them really matter. There’s only so far that style will get you, compared with substance.

Which doesn’t change the fact that I need to wash my car. But procrastination is for another column.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When I was 16, keeping my car shiny was a priority. I washed it every weekend and waxed it once a month. I was pretty good at it and got paid to do the occasional job for a neighbor, too.

In college I was busier, and my car was back at the house, so it didn’t need to be washed as much.

In medical school I think I washed the car once a year. Residency was probably the same.

Today I realized I couldn’t remember when I last had it washed (at my age I don’t have time to do it myself). So I looked it up in Quicken: Nov. 14, 2018.

Really? I’ve gone almost 5 years without washing my car? I can’t even blame that on the pandemic.

I mean, I still like my car. It’s comfortable, has good air conditioning (in Phoenix that’s critical), and gets me where I want to go. At my age those things are what’s really important. It’s hard to believe that 40 years ago, keeping a polished car was the center of my existence. Of course, it probably still is for most guys that age.

It’s a reminder of how much things change as life goes by.

Here in my little corner of neurology, multiple sclerosis has gone from steroids for relapses, to a few injections of mild benefit, to a bunch of drugs that are, literally, game-changing for many patients. And the Big Four epilepsy drugs (Dilantin, Tegretol, Depakote, and Phenobarb) are slowly fading into the background.

But back to changing priorities – it’s the way life rewrites our plans at each step. From a freshly waxed car to good grades to mortgages to kids – and then watching as they wax their cars.

Suddenly my car looks dusty. Am I the same way? I’m certainly not 16 anymore. Realistically, the majority of my life and career are behind me now. That doesn’t mean I’m not still having fun, it’s just the truth. I try not to think about it that much, as doing so won’t change anything.

In all honesty, neither did washing my car. I mean, the car looked good, but did it make me one of the cool kids? Or get me a girlfriend? Or invited to THE parties? Not at all. Like so many things about appearances, very few of them really matter. There’s only so far that style will get you, compared with substance.

Which doesn’t change the fact that I need to wash my car. But procrastination is for another column.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When I was 16, keeping my car shiny was a priority. I washed it every weekend and waxed it once a month. I was pretty good at it and got paid to do the occasional job for a neighbor, too.

In college I was busier, and my car was back at the house, so it didn’t need to be washed as much.

In medical school I think I washed the car once a year. Residency was probably the same.

Today I realized I couldn’t remember when I last had it washed (at my age I don’t have time to do it myself). So I looked it up in Quicken: Nov. 14, 2018.

Really? I’ve gone almost 5 years without washing my car? I can’t even blame that on the pandemic.

I mean, I still like my car. It’s comfortable, has good air conditioning (in Phoenix that’s critical), and gets me where I want to go. At my age those things are what’s really important. It’s hard to believe that 40 years ago, keeping a polished car was the center of my existence. Of course, it probably still is for most guys that age.

It’s a reminder of how much things change as life goes by.

Here in my little corner of neurology, multiple sclerosis has gone from steroids for relapses, to a few injections of mild benefit, to a bunch of drugs that are, literally, game-changing for many patients. And the Big Four epilepsy drugs (Dilantin, Tegretol, Depakote, and Phenobarb) are slowly fading into the background.

But back to changing priorities – it’s the way life rewrites our plans at each step. From a freshly waxed car to good grades to mortgages to kids – and then watching as they wax their cars.

Suddenly my car looks dusty. Am I the same way? I’m certainly not 16 anymore. Realistically, the majority of my life and career are behind me now. That doesn’t mean I’m not still having fun, it’s just the truth. I try not to think about it that much, as doing so won’t change anything.

In all honesty, neither did washing my car. I mean, the car looked good, but did it make me one of the cool kids? Or get me a girlfriend? Or invited to THE parties? Not at all. Like so many things about appearances, very few of them really matter. There’s only so far that style will get you, compared with substance.

Which doesn’t change the fact that I need to wash my car. But procrastination is for another column.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The magic of music

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

It’s not an assembly line

A lot of businesses benefit from being in private equity funds.

Health care isn’t one of them, and a recent report found that

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. Such funds may offer glittering phrases like “improved technology” and “greater efficiency” but the bottom line is that they’re run by – and for – the shareholders. The majority of them aren’t going to be medical people or realize that you can’t run a medical practice like it’s a clothing retailer or electronic car manufacturer.

I’m not saying medicine isn’t a business – it is. I depend on my little practice to support three families, so keeping it in the black is important. But it also needs to run well to do that. Measures to increase revenue, like cutting my staff down (there are only two of them) or overbooking patients would seriously impact me effectively doing my part, which is playing doctor.

You can predict pretty accurately how long it will take to put a motor and bumper assembly on a specific model of car, but you can’t do that in medicine because people aren’t standardized. Even if you control variables such as same sex, age, and diagnosis, personalities vary widely, as do treatment decisions, questions they’ll have, and the “oh, another thing” factor.

That doesn’t happen at a bottling plant.

In the business model of health care, you’re hoping revenue will pay overhead and a reasonable salary for everyone. But when you add a private equity firm in, the shareholders also expect to be paid. Which means either revenue has to go up significantly, or costs have to be cut (layoffs, short staffing, reduced benefits, etc.), or a combination of both.

Regardless of which option is chosen, it isn’t good for the medical staff or the patients. Increasing the number of people seen in a given amount of time per doctor may be good for the shareholders, but it’s not good for the doctor or the person being cared for. Think of Lucy and Ethyl at the chocolate factory.

Even in an auto factory, if you speed up the rate of cars going through the assembly line, sooner or later mistakes will be made. Humans can’t keep up, and even robots will make errors if things aren’t aligned correctly, or are a few seconds ahead or behind the program. This is why they (hopefully) have quality control, to try and catch those things before they’re on the road.

Of course, cars are more easily fixable. When the mistake is found you repair or replace the part. You can’t do that as easily in people, and when serious mistakes happen it’s the doctor who’s held at fault – not the shareholders who pressured him or her to see patients faster and with less support.

Unfortunately, this is the way the current trend is going. The more people who are involved in the practice of medicine, in person or behind the scenes, the smaller each slice of the pie gets.

That’s not good for the patient, who’s the person at the center of it all and the reason why we’re here.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A lot of businesses benefit from being in private equity funds.

Health care isn’t one of them, and a recent report found that

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. Such funds may offer glittering phrases like “improved technology” and “greater efficiency” but the bottom line is that they’re run by – and for – the shareholders. The majority of them aren’t going to be medical people or realize that you can’t run a medical practice like it’s a clothing retailer or electronic car manufacturer.

I’m not saying medicine isn’t a business – it is. I depend on my little practice to support three families, so keeping it in the black is important. But it also needs to run well to do that. Measures to increase revenue, like cutting my staff down (there are only two of them) or overbooking patients would seriously impact me effectively doing my part, which is playing doctor.

You can predict pretty accurately how long it will take to put a motor and bumper assembly on a specific model of car, but you can’t do that in medicine because people aren’t standardized. Even if you control variables such as same sex, age, and diagnosis, personalities vary widely, as do treatment decisions, questions they’ll have, and the “oh, another thing” factor.

That doesn’t happen at a bottling plant.

In the business model of health care, you’re hoping revenue will pay overhead and a reasonable salary for everyone. But when you add a private equity firm in, the shareholders also expect to be paid. Which means either revenue has to go up significantly, or costs have to be cut (layoffs, short staffing, reduced benefits, etc.), or a combination of both.

Regardless of which option is chosen, it isn’t good for the medical staff or the patients. Increasing the number of people seen in a given amount of time per doctor may be good for the shareholders, but it’s not good for the doctor or the person being cared for. Think of Lucy and Ethyl at the chocolate factory.

Even in an auto factory, if you speed up the rate of cars going through the assembly line, sooner or later mistakes will be made. Humans can’t keep up, and even robots will make errors if things aren’t aligned correctly, or are a few seconds ahead or behind the program. This is why they (hopefully) have quality control, to try and catch those things before they’re on the road.

Of course, cars are more easily fixable. When the mistake is found you repair or replace the part. You can’t do that as easily in people, and when serious mistakes happen it’s the doctor who’s held at fault – not the shareholders who pressured him or her to see patients faster and with less support.

Unfortunately, this is the way the current trend is going. The more people who are involved in the practice of medicine, in person or behind the scenes, the smaller each slice of the pie gets.

That’s not good for the patient, who’s the person at the center of it all and the reason why we’re here.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A lot of businesses benefit from being in private equity funds.

Health care isn’t one of them, and a recent report found that

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. Such funds may offer glittering phrases like “improved technology” and “greater efficiency” but the bottom line is that they’re run by – and for – the shareholders. The majority of them aren’t going to be medical people or realize that you can’t run a medical practice like it’s a clothing retailer or electronic car manufacturer.

I’m not saying medicine isn’t a business – it is. I depend on my little practice to support three families, so keeping it in the black is important. But it also needs to run well to do that. Measures to increase revenue, like cutting my staff down (there are only two of them) or overbooking patients would seriously impact me effectively doing my part, which is playing doctor.

You can predict pretty accurately how long it will take to put a motor and bumper assembly on a specific model of car, but you can’t do that in medicine because people aren’t standardized. Even if you control variables such as same sex, age, and diagnosis, personalities vary widely, as do treatment decisions, questions they’ll have, and the “oh, another thing” factor.

That doesn’t happen at a bottling plant.

In the business model of health care, you’re hoping revenue will pay overhead and a reasonable salary for everyone. But when you add a private equity firm in, the shareholders also expect to be paid. Which means either revenue has to go up significantly, or costs have to be cut (layoffs, short staffing, reduced benefits, etc.), or a combination of both.

Regardless of which option is chosen, it isn’t good for the medical staff or the patients. Increasing the number of people seen in a given amount of time per doctor may be good for the shareholders, but it’s not good for the doctor or the person being cared for. Think of Lucy and Ethyl at the chocolate factory.

Even in an auto factory, if you speed up the rate of cars going through the assembly line, sooner or later mistakes will be made. Humans can’t keep up, and even robots will make errors if things aren’t aligned correctly, or are a few seconds ahead or behind the program. This is why they (hopefully) have quality control, to try and catch those things before they’re on the road.

Of course, cars are more easily fixable. When the mistake is found you repair or replace the part. You can’t do that as easily in people, and when serious mistakes happen it’s the doctor who’s held at fault – not the shareholders who pressured him or her to see patients faster and with less support.

Unfortunately, this is the way the current trend is going. The more people who are involved in the practice of medicine, in person or behind the scenes, the smaller each slice of the pie gets.

That’s not good for the patient, who’s the person at the center of it all and the reason why we’re here.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Buyer beware

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.

The website was full of testimonials as to how well the treatments worked, primarily from people in their 20s-40s who are, realistically, unlikely to have a pathologically serious cause for memory problems. The site also mentions that you can use it to treat traumatic brain injury, ADHD, learning disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, Parkinson’s disease, autism, dementia, and stroke, though it does clearly state that such use is not FDA approved.

Prices (I assume all cash pay) for the treatment weren’t listed. I guess you have to come to the “free” dinner for those, or submit an online form to the office.

I’m not going to say the advertised treatment doesn’t work. It might, for at least some of those things. A PubMed search tells me it’s under investigation for several of them.

But that doesn’t mean it works. It might, but a lot of things that look promising in early trials end up failing in the long run. So, at least to me, this is no different than people selling various over-the-counter supplements online with all kinds of extravagant claims and testimonials.

I also have to question a treatment targeting young people for memory loss. In neurology we see a lot of that, and know that true pathology is rare. Most of these patients have root issues with depression, or anxiety, or stress that are affecting their memory. That doesn’t make their memory issues any less real, but they shouldn’t be lumped in with neurodegenerative diseases. They need to be correctly diagnosed and treated for what they are.

Maybe it’s just me, but I often see this sort of thing as kind of sketchy – generating business for unproven treatments by selling fear – you need to do something NOW to keep from getting worse. And, of course there’s always the mysterious “they.” The treatments “they” offer don’t work. Why aren’t “they” telling you what really does?

Looking at the restaurant’s online menu, dinners are around $75 per person and the invitation says “seats are limited.” Doing some mental math gives you an idea how many diners need to come, what percentage of them need to sign up for the treatment, and how much it costs to recoup the investment.

Let the buyer beware.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.

The website was full of testimonials as to how well the treatments worked, primarily from people in their 20s-40s who are, realistically, unlikely to have a pathologically serious cause for memory problems. The site also mentions that you can use it to treat traumatic brain injury, ADHD, learning disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, Parkinson’s disease, autism, dementia, and stroke, though it does clearly state that such use is not FDA approved.

Prices (I assume all cash pay) for the treatment weren’t listed. I guess you have to come to the “free” dinner for those, or submit an online form to the office.

I’m not going to say the advertised treatment doesn’t work. It might, for at least some of those things. A PubMed search tells me it’s under investigation for several of them.

But that doesn’t mean it works. It might, but a lot of things that look promising in early trials end up failing in the long run. So, at least to me, this is no different than people selling various over-the-counter supplements online with all kinds of extravagant claims and testimonials.

I also have to question a treatment targeting young people for memory loss. In neurology we see a lot of that, and know that true pathology is rare. Most of these patients have root issues with depression, or anxiety, or stress that are affecting their memory. That doesn’t make their memory issues any less real, but they shouldn’t be lumped in with neurodegenerative diseases. They need to be correctly diagnosed and treated for what they are.

Maybe it’s just me, but I often see this sort of thing as kind of sketchy – generating business for unproven treatments by selling fear – you need to do something NOW to keep from getting worse. And, of course there’s always the mysterious “they.” The treatments “they” offer don’t work. Why aren’t “they” telling you what really does?

Looking at the restaurant’s online menu, dinners are around $75 per person and the invitation says “seats are limited.” Doing some mental math gives you an idea how many diners need to come, what percentage of them need to sign up for the treatment, and how much it costs to recoup the investment.

Let the buyer beware.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.

The website was full of testimonials as to how well the treatments worked, primarily from people in their 20s-40s who are, realistically, unlikely to have a pathologically serious cause for memory problems. The site also mentions that you can use it to treat traumatic brain injury, ADHD, learning disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, Parkinson’s disease, autism, dementia, and stroke, though it does clearly state that such use is not FDA approved.

Prices (I assume all cash pay) for the treatment weren’t listed. I guess you have to come to the “free” dinner for those, or submit an online form to the office.

I’m not going to say the advertised treatment doesn’t work. It might, for at least some of those things. A PubMed search tells me it’s under investigation for several of them.

But that doesn’t mean it works. It might, but a lot of things that look promising in early trials end up failing in the long run. So, at least to me, this is no different than people selling various over-the-counter supplements online with all kinds of extravagant claims and testimonials.

I also have to question a treatment targeting young people for memory loss. In neurology we see a lot of that, and know that true pathology is rare. Most of these patients have root issues with depression, or anxiety, or stress that are affecting their memory. That doesn’t make their memory issues any less real, but they shouldn’t be lumped in with neurodegenerative diseases. They need to be correctly diagnosed and treated for what they are.

Maybe it’s just me, but I often see this sort of thing as kind of sketchy – generating business for unproven treatments by selling fear – you need to do something NOW to keep from getting worse. And, of course there’s always the mysterious “they.” The treatments “they” offer don’t work. Why aren’t “they” telling you what really does?

Looking at the restaurant’s online menu, dinners are around $75 per person and the invitation says “seats are limited.” Doing some mental math gives you an idea how many diners need to come, what percentage of them need to sign up for the treatment, and how much it costs to recoup the investment.

Let the buyer beware.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

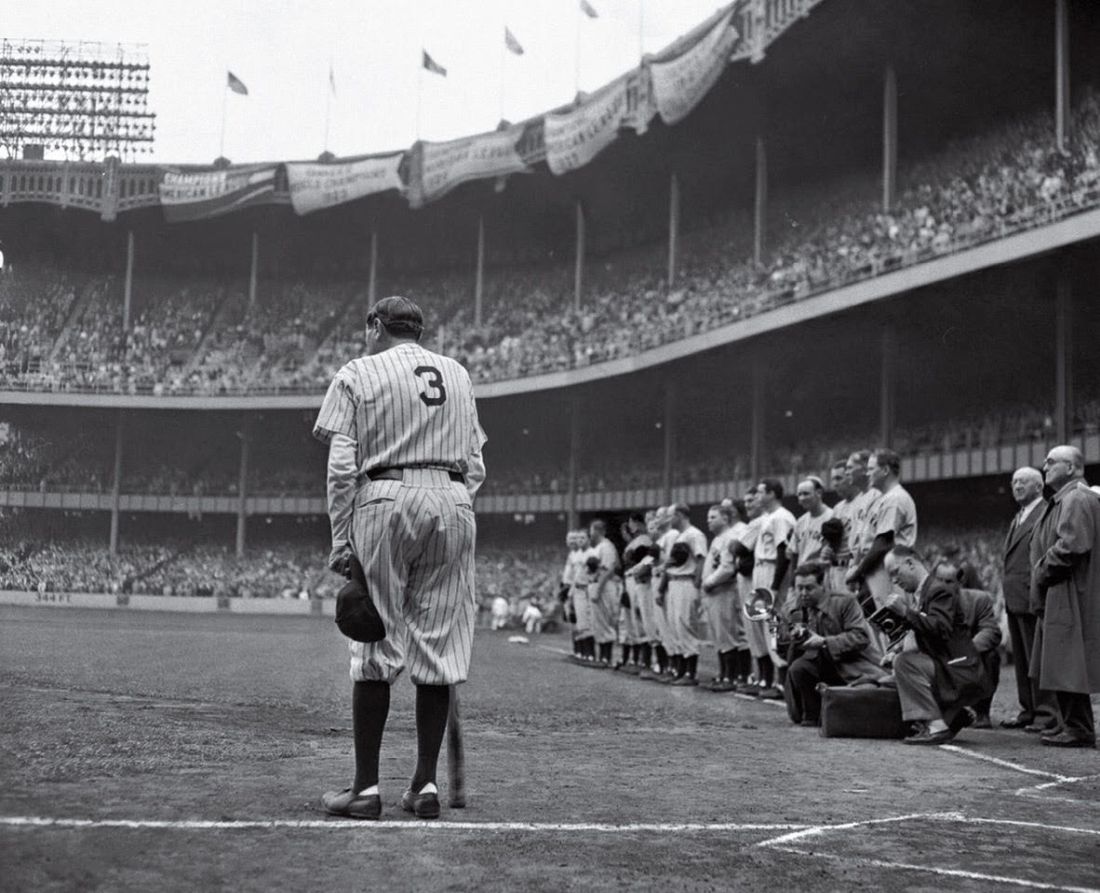

Babe Ruth’s unique cane, and why he used it

Babe Ruth was arguably the greatest athlete in American history.

Certainly, there have been, and always will be, many great figures in all sports. But none of them – Michael Jordan or LeBron James or Tom Brady – have ever, probably will never, dominate sports AND society in the way Babe Ruth did.

Ruth wasn’t an angel, nor did he claim to be. But he was a center of American life the way no athlete ever was or will be.

He was a remarkably good baseball player. In an era where home runs were rarities, he hit more than the entire rest of Major League Baseball combined. But he wasn’t just a slugger, he was an excellent play maker, fielder, and pitcher. (He was actually one of the best pitchers of his era, something else mostly forgotten today.)

Ruth retired in 1935. He never entirely left the limelight, with fans showing up even to watch him play golf in celebrity tournaments. In 1939 he spoke on July 4 at Lou Gehrig appreciation day as his former teammate was publicly dying of ALS.

In 1946 Ruth began having trouble swallowing and developed pain over his right eye. He was found to have nasopharyngeal carcinoma spreading down into his skull base and neck.

Even today surgery to remove cancer from that area is tricky. In 1946 it didn’t exist. An experimental treatment of combined radiation and chemotherapy – today standard – was tried, including a new folic acid derivative called teropterin. He improved somewhat – enough that he was an unnamed case study presented at a medical meeting – but had lost 80 pounds. After a brief respite he continued to go downhill. On June 13, 1948, he appeared at Yankee Stadium – the house that Ruth built – for the last time, where he was honored. He had difficulty walking and used a baseball bat as a cane. His pharynx was so damaged his voice could barely be heard. He died 2 months later on Aug. 16, 1948.

This isn’t a sports column, I’m not a sports writer, and this definitely ain’t Sport Illustrated. So why am I writing this?

Because Babe Ruth never knew he had cancer. Was never told he was dying. His family was afraid he’d harm himself if he knew, so his doctors were under strict instructions to keep the bad news from him.

Now, Ruth wasn’t stupid. Wild, unrepentant, hedonistic, and a lot of other things – but not stupid. He certainly must have figured it out with getting radiation, or chemotherapy, or his declining physical status. But none of his doctors or family ever told him he had cancer and was dying (what they did tell him I have no idea).

Let’s look at this as a case history: A 51-year-old male, possessed of all his mental faculties, presents with headaches, dysphonia, and dysphagia. Workup reveals advanced, inoperable, nasopharyngeal cancer. The family is willing to accept treatment, but understands the prognosis is poor. Family members request that, under no circumstances, he be told of the diagnosis or prognosis.

The fact that the patient is probably the biggest celebrity of his era shouldn’t make a difference, but it does.

I’m sure most of us would want to tell the patient. We live in an age of patient autonomy. . But what if the family has concerns that the patient would hurt himself, as Ruth’s family did?

This summer is 75 years since the Babe died. Medicine has changed a lot, but some questions never will.

What would you do?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Babe Ruth was arguably the greatest athlete in American history.

Certainly, there have been, and always will be, many great figures in all sports. But none of them – Michael Jordan or LeBron James or Tom Brady – have ever, probably will never, dominate sports AND society in the way Babe Ruth did.

Ruth wasn’t an angel, nor did he claim to be. But he was a center of American life the way no athlete ever was or will be.

He was a remarkably good baseball player. In an era where home runs were rarities, he hit more than the entire rest of Major League Baseball combined. But he wasn’t just a slugger, he was an excellent play maker, fielder, and pitcher. (He was actually one of the best pitchers of his era, something else mostly forgotten today.)

Ruth retired in 1935. He never entirely left the limelight, with fans showing up even to watch him play golf in celebrity tournaments. In 1939 he spoke on July 4 at Lou Gehrig appreciation day as his former teammate was publicly dying of ALS.

In 1946 Ruth began having trouble swallowing and developed pain over his right eye. He was found to have nasopharyngeal carcinoma spreading down into his skull base and neck.

Even today surgery to remove cancer from that area is tricky. In 1946 it didn’t exist. An experimental treatment of combined radiation and chemotherapy – today standard – was tried, including a new folic acid derivative called teropterin. He improved somewhat – enough that he was an unnamed case study presented at a medical meeting – but had lost 80 pounds. After a brief respite he continued to go downhill. On June 13, 1948, he appeared at Yankee Stadium – the house that Ruth built – for the last time, where he was honored. He had difficulty walking and used a baseball bat as a cane. His pharynx was so damaged his voice could barely be heard. He died 2 months later on Aug. 16, 1948.

This isn’t a sports column, I’m not a sports writer, and this definitely ain’t Sport Illustrated. So why am I writing this?

Because Babe Ruth never knew he had cancer. Was never told he was dying. His family was afraid he’d harm himself if he knew, so his doctors were under strict instructions to keep the bad news from him.

Now, Ruth wasn’t stupid. Wild, unrepentant, hedonistic, and a lot of other things – but not stupid. He certainly must have figured it out with getting radiation, or chemotherapy, or his declining physical status. But none of his doctors or family ever told him he had cancer and was dying (what they did tell him I have no idea).

Let’s look at this as a case history: A 51-year-old male, possessed of all his mental faculties, presents with headaches, dysphonia, and dysphagia. Workup reveals advanced, inoperable, nasopharyngeal cancer. The family is willing to accept treatment, but understands the prognosis is poor. Family members request that, under no circumstances, he be told of the diagnosis or prognosis.

The fact that the patient is probably the biggest celebrity of his era shouldn’t make a difference, but it does.

I’m sure most of us would want to tell the patient. We live in an age of patient autonomy. . But what if the family has concerns that the patient would hurt himself, as Ruth’s family did?

This summer is 75 years since the Babe died. Medicine has changed a lot, but some questions never will.

What would you do?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Babe Ruth was arguably the greatest athlete in American history.

Certainly, there have been, and always will be, many great figures in all sports. But none of them – Michael Jordan or LeBron James or Tom Brady – have ever, probably will never, dominate sports AND society in the way Babe Ruth did.

Ruth wasn’t an angel, nor did he claim to be. But he was a center of American life the way no athlete ever was or will be.

He was a remarkably good baseball player. In an era where home runs were rarities, he hit more than the entire rest of Major League Baseball combined. But he wasn’t just a slugger, he was an excellent play maker, fielder, and pitcher. (He was actually one of the best pitchers of his era, something else mostly forgotten today.)

Ruth retired in 1935. He never entirely left the limelight, with fans showing up even to watch him play golf in celebrity tournaments. In 1939 he spoke on July 4 at Lou Gehrig appreciation day as his former teammate was publicly dying of ALS.

In 1946 Ruth began having trouble swallowing and developed pain over his right eye. He was found to have nasopharyngeal carcinoma spreading down into his skull base and neck.

Even today surgery to remove cancer from that area is tricky. In 1946 it didn’t exist. An experimental treatment of combined radiation and chemotherapy – today standard – was tried, including a new folic acid derivative called teropterin. He improved somewhat – enough that he was an unnamed case study presented at a medical meeting – but had lost 80 pounds. After a brief respite he continued to go downhill. On June 13, 1948, he appeared at Yankee Stadium – the house that Ruth built – for the last time, where he was honored. He had difficulty walking and used a baseball bat as a cane. His pharynx was so damaged his voice could barely be heard. He died 2 months later on Aug. 16, 1948.

This isn’t a sports column, I’m not a sports writer, and this definitely ain’t Sport Illustrated. So why am I writing this?

Because Babe Ruth never knew he had cancer. Was never told he was dying. His family was afraid he’d harm himself if he knew, so his doctors were under strict instructions to keep the bad news from him.

Now, Ruth wasn’t stupid. Wild, unrepentant, hedonistic, and a lot of other things – but not stupid. He certainly must have figured it out with getting radiation, or chemotherapy, or his declining physical status. But none of his doctors or family ever told him he had cancer and was dying (what they did tell him I have no idea).

Let’s look at this as a case history: A 51-year-old male, possessed of all his mental faculties, presents with headaches, dysphonia, and dysphagia. Workup reveals advanced, inoperable, nasopharyngeal cancer. The family is willing to accept treatment, but understands the prognosis is poor. Family members request that, under no circumstances, he be told of the diagnosis or prognosis.

The fact that the patient is probably the biggest celebrity of his era shouldn’t make a difference, but it does.

I’m sure most of us would want to tell the patient. We live in an age of patient autonomy. . But what if the family has concerns that the patient would hurt himself, as Ruth’s family did?

This summer is 75 years since the Babe died. Medicine has changed a lot, but some questions never will.

What would you do?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Sick humor

This past June, during the search for the Titan submersible, and since then, we’ve had a not-entirely-unexpected development: Sick humor.

There was a lot of it. The Subway owner who got reprimanded for putting “Our subs don’t implode” on his sign was minor league compared with other things circulating on the Internet. One example that was sent to me showed the late Stockton Rush, OceanGate’s co-owner, as the new spokesman for Cap’n Crunch.

Of course, this is nothing new. People have made jokes about awful situations since to the dawn of civilization.

Why do we do this?

Humor is a remarkably human trait. There’s evidence other mammals have it, but not to the extent we do. We’ve created a multitude of forms that vary between cultures. But there isn’t a civilization or culture on Earth that doesn’t have humor.

Why we developed it I’ll leave to others, though I assume a key part is that it strengthens bonds between people, helping them stick together in the groups that keep society moving forward.

Sick humor is part of this, though having grown up watching Monty Python and reading National Lampoon magazine I’m certainly guilty of enjoying it. To this day I think “Eating Raoul” is one of the greatest comedies ever.

It’s also pretty common in medicine. I’ve been involved in plenty of hospital situations that were quite unfunny, yet there are always jokes about it flying as we work.

I assume it’s a defense mechanism. Helping us cope with a bad situation as we do our best to deal with it. Using humor to put a block between the obvious realization that someday this could happen to us. To help psychologically shield us from something tragic.

Years ago I was trying to describe the plot of “Eating Raoul” and said “if you read about this sort of crime spree in a newspaper you’d be horrified. But the way it’s handled in the movie it’s hysterical.” Perhaps that’s as close to understanding sick humor as I’ll ever get. It makes the unfunny funny.

Perhaps the better phrase is the more generic “it’s human nature.”

Whether or not it’s funny depends on the person. There were plenty of people horrified by the Subway sign, enough that the owner had to change it. But there were also those who admitted they found it tasteless, but still got a laugh out of it. I’m sure the families of those lost on the Titan were justifiably upset, but the closer you get to a personal tragedy the more serious it is.

There’s a fine line, as National Lampoon put it, between funny and sick. But it’s also part of who we are.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This past June, during the search for the Titan submersible, and since then, we’ve had a not-entirely-unexpected development: Sick humor.

There was a lot of it. The Subway owner who got reprimanded for putting “Our subs don’t implode” on his sign was minor league compared with other things circulating on the Internet. One example that was sent to me showed the late Stockton Rush, OceanGate’s co-owner, as the new spokesman for Cap’n Crunch.

Of course, this is nothing new. People have made jokes about awful situations since to the dawn of civilization.

Why do we do this?

Humor is a remarkably human trait. There’s evidence other mammals have it, but not to the extent we do. We’ve created a multitude of forms that vary between cultures. But there isn’t a civilization or culture on Earth that doesn’t have humor.

Why we developed it I’ll leave to others, though I assume a key part is that it strengthens bonds between people, helping them stick together in the groups that keep society moving forward.

Sick humor is part of this, though having grown up watching Monty Python and reading National Lampoon magazine I’m certainly guilty of enjoying it. To this day I think “Eating Raoul” is one of the greatest comedies ever.

It’s also pretty common in medicine. I’ve been involved in plenty of hospital situations that were quite unfunny, yet there are always jokes about it flying as we work.

I assume it’s a defense mechanism. Helping us cope with a bad situation as we do our best to deal with it. Using humor to put a block between the obvious realization that someday this could happen to us. To help psychologically shield us from something tragic.

Years ago I was trying to describe the plot of “Eating Raoul” and said “if you read about this sort of crime spree in a newspaper you’d be horrified. But the way it’s handled in the movie it’s hysterical.” Perhaps that’s as close to understanding sick humor as I’ll ever get. It makes the unfunny funny.

Perhaps the better phrase is the more generic “it’s human nature.”

Whether or not it’s funny depends on the person. There were plenty of people horrified by the Subway sign, enough that the owner had to change it. But there were also those who admitted they found it tasteless, but still got a laugh out of it. I’m sure the families of those lost on the Titan were justifiably upset, but the closer you get to a personal tragedy the more serious it is.

There’s a fine line, as National Lampoon put it, between funny and sick. But it’s also part of who we are.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This past June, during the search for the Titan submersible, and since then, we’ve had a not-entirely-unexpected development: Sick humor.

There was a lot of it. The Subway owner who got reprimanded for putting “Our subs don’t implode” on his sign was minor league compared with other things circulating on the Internet. One example that was sent to me showed the late Stockton Rush, OceanGate’s co-owner, as the new spokesman for Cap’n Crunch.

Of course, this is nothing new. People have made jokes about awful situations since to the dawn of civilization.

Why do we do this?

Humor is a remarkably human trait. There’s evidence other mammals have it, but not to the extent we do. We’ve created a multitude of forms that vary between cultures. But there isn’t a civilization or culture on Earth that doesn’t have humor.

Why we developed it I’ll leave to others, though I assume a key part is that it strengthens bonds between people, helping them stick together in the groups that keep society moving forward.

Sick humor is part of this, though having grown up watching Monty Python and reading National Lampoon magazine I’m certainly guilty of enjoying it. To this day I think “Eating Raoul” is one of the greatest comedies ever.

It’s also pretty common in medicine. I’ve been involved in plenty of hospital situations that were quite unfunny, yet there are always jokes about it flying as we work.

I assume it’s a defense mechanism. Helping us cope with a bad situation as we do our best to deal with it. Using humor to put a block between the obvious realization that someday this could happen to us. To help psychologically shield us from something tragic.

Years ago I was trying to describe the plot of “Eating Raoul” and said “if you read about this sort of crime spree in a newspaper you’d be horrified. But the way it’s handled in the movie it’s hysterical.” Perhaps that’s as close to understanding sick humor as I’ll ever get. It makes the unfunny funny.

Perhaps the better phrase is the more generic “it’s human nature.”

Whether or not it’s funny depends on the person. There were plenty of people horrified by the Subway sign, enough that the owner had to change it. But there were also those who admitted they found it tasteless, but still got a laugh out of it. I’m sure the families of those lost on the Titan were justifiably upset, but the closer you get to a personal tragedy the more serious it is.

There’s a fine line, as National Lampoon put it, between funny and sick. But it’s also part of who we are.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Looking back and looking ahead

This last week I quietly reached a milestone. I didn’t do anything special about it; it was just another office day.

I passed 25 years since I first began seeing patients as an attending physician. That’s a pretty decent chunk of time.

I was terrified that day. For the first time in my medical career I was working without a net. I even remember the first one, a fellow with back pain. I saw five to six patients that day that I recall, including a work-in from the fellowship I’d completed 2 weeks earlier. I also had my first hospital consult when the oncologist I was subleasing from asked me to have a look at a lady he was admitting for new-onset diplopia.

That’s a good chuck of a career behind me, when you consider the beginnings of it. College, MCATs, waiting by the mailbox (yeah, kids, a mailbox, waiting for a printed letter, delivered by the postman). Moving halfway across the country for 4 years. Somehow, to my own amazement, graduating. Moving back. Internship. Residency. Fellowship.

Then my first day as an attending, now a quarter-century gone. Looking at my charts I’ve seen roughly 18,000 individual patients over time between my office and the hospital.

But that’s another change – after 22 years in the trenches, I stopped doing hospital work over 3 years ago. Inpatient work, at least to me now, seems more like a younger person’s game. In my late 50s, I don’t think I qualify as one anymore.

On day 1, also in the Phoenix summer, I wore a long-sleeved shirt, tie, slacks, and neatly polished shoes. In 2006 I moved to Hawaiian shirts, shorts, and sneakers.

I don’t plan on doing this in another 25 years. I still like it, but by then I will have passed the baton to another generation and will be off on a cruise ship having boat drinks in the afternoon.

But that’s not to say it hasn’t been fun. For all the frustrations, stresses, and aggravations, I have no regrets over the road I’ve taken, and hopefully I will always feel that way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This last week I quietly reached a milestone. I didn’t do anything special about it; it was just another office day.

I passed 25 years since I first began seeing patients as an attending physician. That’s a pretty decent chunk of time.

I was terrified that day. For the first time in my medical career I was working without a net. I even remember the first one, a fellow with back pain. I saw five to six patients that day that I recall, including a work-in from the fellowship I’d completed 2 weeks earlier. I also had my first hospital consult when the oncologist I was subleasing from asked me to have a look at a lady he was admitting for new-onset diplopia.

That’s a good chuck of a career behind me, when you consider the beginnings of it. College, MCATs, waiting by the mailbox (yeah, kids, a mailbox, waiting for a printed letter, delivered by the postman). Moving halfway across the country for 4 years. Somehow, to my own amazement, graduating. Moving back. Internship. Residency. Fellowship.

Then my first day as an attending, now a quarter-century gone. Looking at my charts I’ve seen roughly 18,000 individual patients over time between my office and the hospital.

But that’s another change – after 22 years in the trenches, I stopped doing hospital work over 3 years ago. Inpatient work, at least to me now, seems more like a younger person’s game. In my late 50s, I don’t think I qualify as one anymore.

On day 1, also in the Phoenix summer, I wore a long-sleeved shirt, tie, slacks, and neatly polished shoes. In 2006 I moved to Hawaiian shirts, shorts, and sneakers.

I don’t plan on doing this in another 25 years. I still like it, but by then I will have passed the baton to another generation and will be off on a cruise ship having boat drinks in the afternoon.

But that’s not to say it hasn’t been fun. For all the frustrations, stresses, and aggravations, I have no regrets over the road I’ve taken, and hopefully I will always feel that way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This last week I quietly reached a milestone. I didn’t do anything special about it; it was just another office day.

I passed 25 years since I first began seeing patients as an attending physician. That’s a pretty decent chunk of time.

I was terrified that day. For the first time in my medical career I was working without a net. I even remember the first one, a fellow with back pain. I saw five to six patients that day that I recall, including a work-in from the fellowship I’d completed 2 weeks earlier. I also had my first hospital consult when the oncologist I was subleasing from asked me to have a look at a lady he was admitting for new-onset diplopia.

That’s a good chuck of a career behind me, when you consider the beginnings of it. College, MCATs, waiting by the mailbox (yeah, kids, a mailbox, waiting for a printed letter, delivered by the postman). Moving halfway across the country for 4 years. Somehow, to my own amazement, graduating. Moving back. Internship. Residency. Fellowship.

Then my first day as an attending, now a quarter-century gone. Looking at my charts I’ve seen roughly 18,000 individual patients over time between my office and the hospital.

But that’s another change – after 22 years in the trenches, I stopped doing hospital work over 3 years ago. Inpatient work, at least to me now, seems more like a younger person’s game. In my late 50s, I don’t think I qualify as one anymore.

On day 1, also in the Phoenix summer, I wore a long-sleeved shirt, tie, slacks, and neatly polished shoes. In 2006 I moved to Hawaiian shirts, shorts, and sneakers.

I don’t plan on doing this in another 25 years. I still like it, but by then I will have passed the baton to another generation and will be off on a cruise ship having boat drinks in the afternoon.

But that’s not to say it hasn’t been fun. For all the frustrations, stresses, and aggravations, I have no regrets over the road I’ve taken, and hopefully I will always feel that way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.