User login

VA SHIELD: A Biorepository for Veterans and the Nation

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinicians, clinician-investigators, and investigators perform basic and translational research for the benefit of our nation and are widely recognized for treating patients and discovering cures.1,2 In May 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) launched the VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD). The goal of this novel enterprise was to assemble a comprehensive specimen and data repository for emerging life-threatening diseases and to address future challenges. VA SHIELD was specifically charged with creating a biorepository to advance research, improve diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities, and develop strategies for immediate deployment to VA clinical environments. One main objective of VA SHIELD is to harness the clinical and scientific strengths of the VA in order to create a more cohesive collaboration between preexisting clinical research efforts within the VA.

ANATOMY OF VA SHIELD

The charge and scope of VA SHIELD is unique.3 As an entity, this program leverages the strengths of the diverse VHA network, has a broad potential impact on national health care, is positioned to respond rapidly to national and international health-related events, and substantially contributes to clinical research and development. In addition, VA SHIELD upholds VA’s Fourth Mission, which is to contribute to national emergencies and support emergency management, public health, safety, and homeland security efforts.

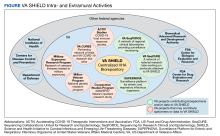

VA SHIELD is part of the VA Office of Research and Development (ORD). The coordinating center (CC), headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, is the central operational partner, leading VA SHIELD and interacting with other important VA programs, including laboratory, clinical science, rehabilitation, and health services. The VA SHIELD CC oversees all aspects of operations, including biospecimen collection, creating and enforcing of standard operating procedures, ensuring the quality of the samples, processing research applications, distribution of samples, financing, and progress reports. The CC also initiates and maintains interagency collaborations, convenes stakeholders, and develops strategic plans to address emerging diseases.

The VA SHIELD Executive Steering Committee (ESC) is composed of infectious disease, biorepository, and public health specialists. The ESC provides scientific and programmatic direction to the CC, including operational activities and guidance regarding biorepository priorities and scientific agenda, and measuring and reporting on VA SHIELD accomplishments.

The primary function of the Programmatic and Scientific Review Board (PSRB) is to evaluate incoming research proposals for specimen and data use for feasibility and make recommendations to the VA SHIELD CC. The PSRB evaluates and ensures that data and specimen use align with VA SHIELD ethical, clinical, and scientific objectives.

VA SHIELD IN PRACTICE

VA SHIELD consisted of 11 specimen collection sites (Atlanta, GA; Boise, ID; Bronx, NY; Cincinnati, OH; Cleveland, OH; Durham, NC; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Mountain Home, TN; Palo Alto, CA; and Tucson, AZ), a data processing center in Boston, MA, and 2 central biorepositories in Palo Alto, CA, and Tucson, AZ. Information flow is a coordinated process among specimen collection sites, data processing centers, and the biorepositories. Initially, each local collection site identifies residual specimens that would have been discarded after clinical laboratory testing. These samples currently account for the majority of biological material within VA SHIELD via a novel collection protocol known as “Sweep,” which allows residual clinical discarded samples as well as samples from patients with new emerging infectious and noninfectious diseases of concern to be collected at the time of first emergence and submitted to VA SHIELD during the course of routine veteran health care.3 These clinical discarded samples are de-identified and transferred from the clinical laboratory to VA SHIELD. The VA Central Institutional Review Board (cIRB) has approved the use of these samples as nonhuman subject research. Biological samples are collected, processed, aliquoted, shipped to, and stored at the central biorepository sites.

The Umbrella amendment to Sweep that has been approved also by the VA cIRB, will allow VA SHIELD sites to prospectively consent veterans and collect biospecimens and additional clinical and self-reported information. The implementation of Umbrella could significantly enhance collection and research. Although Sweep is a onetime collection of samples, the Umbrella protocol will allow the longitudinal collection of samples from the same patient. Additionally, the Umbrella amendment will allow VA SHIELD to accept samples from other preexisting biorepositories or specimen collections.

Central Biorepositories

VA SHIELD has a federated organization with 2 central specimen biorepositories (Palo Alto, CA and Tucson, AZ), and an enterprise data processing center (Boston, MA). The specimen biorepositories receive de-identified specimens that are stored until distribution to approved research projects. The samples and data are linked using an electronic honest broker system to protect privacy, which integrates de-identified specimens with requested clinical and demographic data as needed for approved projects. The honest broker system is operated by independent personnel and does not have vested interest in any studies being performed under VA SHIELD. The integration of sample and associated data is done only as needed when characterization of the donor/participant is necessary byresearch aims or project outcomes. The process is facilitated by a nationally supported laboratory information management system (LIMS), managed by the VA SHIELD data center, that assists with all data requests. The clinical and demographic data are collected from VA electronic health record (EHR), available through VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) as needed and integrated with the biorepository samples information for approved VA SHIELD studies. The CDW is the largest longitudinal EHR data collection in the US and has the ability to provide access to national clinical and demographic data.

VA SHIELD interacts with multiple VA programs and other entities (Figure). For example, Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (SUPERNOVA) is a network of 5 VA medical centers supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4 Its initial goal was to perform surveillance for acute gastroenteritis. In 2020, SUPERNOVA shifted to conduct surveillance for COVID-19 variants among veterans.5 VA SHIELD also interacts with VHA genomic surveillance and sequencing programs: the VA Sequencing Collaborations United for Research and Epidemiology (SeqCURE) and VA Sequencing for Research Clinical and Epidemiology (SeqFORCE), described by Krishnan and colleagues.6

Working Groups

To encourage research projects that use biospecimens, VA SHIELD developed content-oriented research working groups. The goal is to inspire collaborations between VA scientists and prevent redundant or overlapping projects. Currently working groups are focused on long COVID, and COVID-19 neurology, pathogen host response, epidemiology and sequencing, cancer and cancer biomarkers, antimicrobial resistance, and vector-borne diseases. Working groups meet regularly to discuss projects and report progress. Working groups also may consider samples that might benefit VA health research and identify potential veteran populations for future research. Working groups connect VA SHIELD and investigators and guide the collection and use of resources.

Ethical Considerations

We recognize the significant ethical concerns for biobanking of specimens. However, there is no general consensus or guideline that addresses all of the complex ethical issues regarding biobanking.7 To address these ethical concerns, we applied the VA Ethical Framework Principles for Access to and Use of Veteran Data principles to VA SHIELD, including all parties who oversee the access to, sharing of, or the use of data, or who access or use its data.8

Conclusions

The VA has assembled a scientific enterprise dedicated to combating emerging infectious diseases and other threats to our patients. This enterprise has been modeled in its structure and oversight to support VA SHIELD. The establishment of a real-time biorepository and data procurement system linked to clinical samples is a bold step forward to address current and future challenges. Similarly, the integration and cooperation of multiple arms within the VA that transcend disciplines and boundaries promise to shepherd a new era of system-wide investigation. In the future, VA SHIELD will integrate with other existing government agencies to advance mutual scientific agendas. VA SHIELD has established the data and biorepository infrastructure to develop innovative and novel technologies to address future challenges. The alignment of basic science, clinical, and translational research goals under one governance is a significant advancement compared with previous models of research coordination.

VA SHIELD was developed to meet an immediate need; it was also framed to be a research enterprise that harnesses the robust clinical and research environment in VHA. The VA SHIELD infrastructure was conceptualized to harmonize specimen and data collection across the VA, allowing researchers to leverage broader collection efforts. Building a biorepository and data collection system within the largest integrated health care system has the potential to provide a lasting impact on VHA and on our nation’s health.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Daphne Swancutt for her contribution as copywriter for this manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge the VA SHIELD investigators: Mary Cloud Ammons, David Beenhouwer, Sheldon T. Brown, Victoria Davey, Abhinav Diwan, John B. Harley, Mark Holodniy, Vincent C. Marconi, Jonathan Moorman, Emerson B. Padiernos, Ian F. Robey, Maria Rodriguez-Barradas, Jason Wertheim, Christopher W. Woods.

1. Lipshy KA, Itani K, Chu D, et al. Sentinel contributions of US Department of Veterans Affairs surgeons in shaping the face of health care. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(4):380-386. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.6372

2. Zucker S, Crabbe JC, Cooper G 4th, et al. Veterans Administration support for medical research: opinions of the endangered species of physician-scientists. FASEB J. 2004;18(13):1481-1486. doi:10.1096/fj.04-1573lfe

3. Harley JB, Pyarajan S, Partan ES, et al. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD): a biorepository addressing national health threats. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac641. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac641

4. Meites E, Bajema KL, Kambhampati A, et al; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group. Adapting the Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (SUPERNOVA) for COVID-19 among hospitalized adults: surveillance protocol. Front Public Health. 2021;9:739076. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.739076

5. Bajema KL, Dahl RM, Evener SL, et al; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group; Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at the VA (SUPERNOVA) COVID-19 Surveillance Group. Comparative effectiveness and antibody responses to Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines among hospitalized veterans–five Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, United States, February 1-September 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(49):1700-1705. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7049a2external icon

6. Krishnan J, Woods C, Holodniy M, et al. Nationwide genomic surveillance and response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): SeqCURE and SeqFORCE consortiums. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S44-S47. doi:10.12788/fp.0417

7. Ashcroft JW, Macpherson CC. The complex ethical landscape of biobanking. Lancet Public Health. 2019;(6):e274-e275. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30081-7

8. Principle-Based Ethics Framework for Access to and Use of Veteran Data. Fed Regist. 2022;87(129):40451-40452.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinicians, clinician-investigators, and investigators perform basic and translational research for the benefit of our nation and are widely recognized for treating patients and discovering cures.1,2 In May 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) launched the VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD). The goal of this novel enterprise was to assemble a comprehensive specimen and data repository for emerging life-threatening diseases and to address future challenges. VA SHIELD was specifically charged with creating a biorepository to advance research, improve diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities, and develop strategies for immediate deployment to VA clinical environments. One main objective of VA SHIELD is to harness the clinical and scientific strengths of the VA in order to create a more cohesive collaboration between preexisting clinical research efforts within the VA.

ANATOMY OF VA SHIELD

The charge and scope of VA SHIELD is unique.3 As an entity, this program leverages the strengths of the diverse VHA network, has a broad potential impact on national health care, is positioned to respond rapidly to national and international health-related events, and substantially contributes to clinical research and development. In addition, VA SHIELD upholds VA’s Fourth Mission, which is to contribute to national emergencies and support emergency management, public health, safety, and homeland security efforts.

VA SHIELD is part of the VA Office of Research and Development (ORD). The coordinating center (CC), headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, is the central operational partner, leading VA SHIELD and interacting with other important VA programs, including laboratory, clinical science, rehabilitation, and health services. The VA SHIELD CC oversees all aspects of operations, including biospecimen collection, creating and enforcing of standard operating procedures, ensuring the quality of the samples, processing research applications, distribution of samples, financing, and progress reports. The CC also initiates and maintains interagency collaborations, convenes stakeholders, and develops strategic plans to address emerging diseases.

The VA SHIELD Executive Steering Committee (ESC) is composed of infectious disease, biorepository, and public health specialists. The ESC provides scientific and programmatic direction to the CC, including operational activities and guidance regarding biorepository priorities and scientific agenda, and measuring and reporting on VA SHIELD accomplishments.

The primary function of the Programmatic and Scientific Review Board (PSRB) is to evaluate incoming research proposals for specimen and data use for feasibility and make recommendations to the VA SHIELD CC. The PSRB evaluates and ensures that data and specimen use align with VA SHIELD ethical, clinical, and scientific objectives.

VA SHIELD IN PRACTICE

VA SHIELD consisted of 11 specimen collection sites (Atlanta, GA; Boise, ID; Bronx, NY; Cincinnati, OH; Cleveland, OH; Durham, NC; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Mountain Home, TN; Palo Alto, CA; and Tucson, AZ), a data processing center in Boston, MA, and 2 central biorepositories in Palo Alto, CA, and Tucson, AZ. Information flow is a coordinated process among specimen collection sites, data processing centers, and the biorepositories. Initially, each local collection site identifies residual specimens that would have been discarded after clinical laboratory testing. These samples currently account for the majority of biological material within VA SHIELD via a novel collection protocol known as “Sweep,” which allows residual clinical discarded samples as well as samples from patients with new emerging infectious and noninfectious diseases of concern to be collected at the time of first emergence and submitted to VA SHIELD during the course of routine veteran health care.3 These clinical discarded samples are de-identified and transferred from the clinical laboratory to VA SHIELD. The VA Central Institutional Review Board (cIRB) has approved the use of these samples as nonhuman subject research. Biological samples are collected, processed, aliquoted, shipped to, and stored at the central biorepository sites.

The Umbrella amendment to Sweep that has been approved also by the VA cIRB, will allow VA SHIELD sites to prospectively consent veterans and collect biospecimens and additional clinical and self-reported information. The implementation of Umbrella could significantly enhance collection and research. Although Sweep is a onetime collection of samples, the Umbrella protocol will allow the longitudinal collection of samples from the same patient. Additionally, the Umbrella amendment will allow VA SHIELD to accept samples from other preexisting biorepositories or specimen collections.

Central Biorepositories

VA SHIELD has a federated organization with 2 central specimen biorepositories (Palo Alto, CA and Tucson, AZ), and an enterprise data processing center (Boston, MA). The specimen biorepositories receive de-identified specimens that are stored until distribution to approved research projects. The samples and data are linked using an electronic honest broker system to protect privacy, which integrates de-identified specimens with requested clinical and demographic data as needed for approved projects. The honest broker system is operated by independent personnel and does not have vested interest in any studies being performed under VA SHIELD. The integration of sample and associated data is done only as needed when characterization of the donor/participant is necessary byresearch aims or project outcomes. The process is facilitated by a nationally supported laboratory information management system (LIMS), managed by the VA SHIELD data center, that assists with all data requests. The clinical and demographic data are collected from VA electronic health record (EHR), available through VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) as needed and integrated with the biorepository samples information for approved VA SHIELD studies. The CDW is the largest longitudinal EHR data collection in the US and has the ability to provide access to national clinical and demographic data.

VA SHIELD interacts with multiple VA programs and other entities (Figure). For example, Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (SUPERNOVA) is a network of 5 VA medical centers supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4 Its initial goal was to perform surveillance for acute gastroenteritis. In 2020, SUPERNOVA shifted to conduct surveillance for COVID-19 variants among veterans.5 VA SHIELD also interacts with VHA genomic surveillance and sequencing programs: the VA Sequencing Collaborations United for Research and Epidemiology (SeqCURE) and VA Sequencing for Research Clinical and Epidemiology (SeqFORCE), described by Krishnan and colleagues.6

Working Groups

To encourage research projects that use biospecimens, VA SHIELD developed content-oriented research working groups. The goal is to inspire collaborations between VA scientists and prevent redundant or overlapping projects. Currently working groups are focused on long COVID, and COVID-19 neurology, pathogen host response, epidemiology and sequencing, cancer and cancer biomarkers, antimicrobial resistance, and vector-borne diseases. Working groups meet regularly to discuss projects and report progress. Working groups also may consider samples that might benefit VA health research and identify potential veteran populations for future research. Working groups connect VA SHIELD and investigators and guide the collection and use of resources.

Ethical Considerations

We recognize the significant ethical concerns for biobanking of specimens. However, there is no general consensus or guideline that addresses all of the complex ethical issues regarding biobanking.7 To address these ethical concerns, we applied the VA Ethical Framework Principles for Access to and Use of Veteran Data principles to VA SHIELD, including all parties who oversee the access to, sharing of, or the use of data, or who access or use its data.8

Conclusions

The VA has assembled a scientific enterprise dedicated to combating emerging infectious diseases and other threats to our patients. This enterprise has been modeled in its structure and oversight to support VA SHIELD. The establishment of a real-time biorepository and data procurement system linked to clinical samples is a bold step forward to address current and future challenges. Similarly, the integration and cooperation of multiple arms within the VA that transcend disciplines and boundaries promise to shepherd a new era of system-wide investigation. In the future, VA SHIELD will integrate with other existing government agencies to advance mutual scientific agendas. VA SHIELD has established the data and biorepository infrastructure to develop innovative and novel technologies to address future challenges. The alignment of basic science, clinical, and translational research goals under one governance is a significant advancement compared with previous models of research coordination.

VA SHIELD was developed to meet an immediate need; it was also framed to be a research enterprise that harnesses the robust clinical and research environment in VHA. The VA SHIELD infrastructure was conceptualized to harmonize specimen and data collection across the VA, allowing researchers to leverage broader collection efforts. Building a biorepository and data collection system within the largest integrated health care system has the potential to provide a lasting impact on VHA and on our nation’s health.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Daphne Swancutt for her contribution as copywriter for this manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge the VA SHIELD investigators: Mary Cloud Ammons, David Beenhouwer, Sheldon T. Brown, Victoria Davey, Abhinav Diwan, John B. Harley, Mark Holodniy, Vincent C. Marconi, Jonathan Moorman, Emerson B. Padiernos, Ian F. Robey, Maria Rodriguez-Barradas, Jason Wertheim, Christopher W. Woods.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinicians, clinician-investigators, and investigators perform basic and translational research for the benefit of our nation and are widely recognized for treating patients and discovering cures.1,2 In May 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) launched the VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD). The goal of this novel enterprise was to assemble a comprehensive specimen and data repository for emerging life-threatening diseases and to address future challenges. VA SHIELD was specifically charged with creating a biorepository to advance research, improve diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities, and develop strategies for immediate deployment to VA clinical environments. One main objective of VA SHIELD is to harness the clinical and scientific strengths of the VA in order to create a more cohesive collaboration between preexisting clinical research efforts within the VA.

ANATOMY OF VA SHIELD

The charge and scope of VA SHIELD is unique.3 As an entity, this program leverages the strengths of the diverse VHA network, has a broad potential impact on national health care, is positioned to respond rapidly to national and international health-related events, and substantially contributes to clinical research and development. In addition, VA SHIELD upholds VA’s Fourth Mission, which is to contribute to national emergencies and support emergency management, public health, safety, and homeland security efforts.

VA SHIELD is part of the VA Office of Research and Development (ORD). The coordinating center (CC), headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, is the central operational partner, leading VA SHIELD and interacting with other important VA programs, including laboratory, clinical science, rehabilitation, and health services. The VA SHIELD CC oversees all aspects of operations, including biospecimen collection, creating and enforcing of standard operating procedures, ensuring the quality of the samples, processing research applications, distribution of samples, financing, and progress reports. The CC also initiates and maintains interagency collaborations, convenes stakeholders, and develops strategic plans to address emerging diseases.

The VA SHIELD Executive Steering Committee (ESC) is composed of infectious disease, biorepository, and public health specialists. The ESC provides scientific and programmatic direction to the CC, including operational activities and guidance regarding biorepository priorities and scientific agenda, and measuring and reporting on VA SHIELD accomplishments.

The primary function of the Programmatic and Scientific Review Board (PSRB) is to evaluate incoming research proposals for specimen and data use for feasibility and make recommendations to the VA SHIELD CC. The PSRB evaluates and ensures that data and specimen use align with VA SHIELD ethical, clinical, and scientific objectives.

VA SHIELD IN PRACTICE

VA SHIELD consisted of 11 specimen collection sites (Atlanta, GA; Boise, ID; Bronx, NY; Cincinnati, OH; Cleveland, OH; Durham, NC; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Mountain Home, TN; Palo Alto, CA; and Tucson, AZ), a data processing center in Boston, MA, and 2 central biorepositories in Palo Alto, CA, and Tucson, AZ. Information flow is a coordinated process among specimen collection sites, data processing centers, and the biorepositories. Initially, each local collection site identifies residual specimens that would have been discarded after clinical laboratory testing. These samples currently account for the majority of biological material within VA SHIELD via a novel collection protocol known as “Sweep,” which allows residual clinical discarded samples as well as samples from patients with new emerging infectious and noninfectious diseases of concern to be collected at the time of first emergence and submitted to VA SHIELD during the course of routine veteran health care.3 These clinical discarded samples are de-identified and transferred from the clinical laboratory to VA SHIELD. The VA Central Institutional Review Board (cIRB) has approved the use of these samples as nonhuman subject research. Biological samples are collected, processed, aliquoted, shipped to, and stored at the central biorepository sites.

The Umbrella amendment to Sweep that has been approved also by the VA cIRB, will allow VA SHIELD sites to prospectively consent veterans and collect biospecimens and additional clinical and self-reported information. The implementation of Umbrella could significantly enhance collection and research. Although Sweep is a onetime collection of samples, the Umbrella protocol will allow the longitudinal collection of samples from the same patient. Additionally, the Umbrella amendment will allow VA SHIELD to accept samples from other preexisting biorepositories or specimen collections.

Central Biorepositories

VA SHIELD has a federated organization with 2 central specimen biorepositories (Palo Alto, CA and Tucson, AZ), and an enterprise data processing center (Boston, MA). The specimen biorepositories receive de-identified specimens that are stored until distribution to approved research projects. The samples and data are linked using an electronic honest broker system to protect privacy, which integrates de-identified specimens with requested clinical and demographic data as needed for approved projects. The honest broker system is operated by independent personnel and does not have vested interest in any studies being performed under VA SHIELD. The integration of sample and associated data is done only as needed when characterization of the donor/participant is necessary byresearch aims or project outcomes. The process is facilitated by a nationally supported laboratory information management system (LIMS), managed by the VA SHIELD data center, that assists with all data requests. The clinical and demographic data are collected from VA electronic health record (EHR), available through VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) as needed and integrated with the biorepository samples information for approved VA SHIELD studies. The CDW is the largest longitudinal EHR data collection in the US and has the ability to provide access to national clinical and demographic data.

VA SHIELD interacts with multiple VA programs and other entities (Figure). For example, Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (SUPERNOVA) is a network of 5 VA medical centers supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4 Its initial goal was to perform surveillance for acute gastroenteritis. In 2020, SUPERNOVA shifted to conduct surveillance for COVID-19 variants among veterans.5 VA SHIELD also interacts with VHA genomic surveillance and sequencing programs: the VA Sequencing Collaborations United for Research and Epidemiology (SeqCURE) and VA Sequencing for Research Clinical and Epidemiology (SeqFORCE), described by Krishnan and colleagues.6

Working Groups

To encourage research projects that use biospecimens, VA SHIELD developed content-oriented research working groups. The goal is to inspire collaborations between VA scientists and prevent redundant or overlapping projects. Currently working groups are focused on long COVID, and COVID-19 neurology, pathogen host response, epidemiology and sequencing, cancer and cancer biomarkers, antimicrobial resistance, and vector-borne diseases. Working groups meet regularly to discuss projects and report progress. Working groups also may consider samples that might benefit VA health research and identify potential veteran populations for future research. Working groups connect VA SHIELD and investigators and guide the collection and use of resources.

Ethical Considerations

We recognize the significant ethical concerns for biobanking of specimens. However, there is no general consensus or guideline that addresses all of the complex ethical issues regarding biobanking.7 To address these ethical concerns, we applied the VA Ethical Framework Principles for Access to and Use of Veteran Data principles to VA SHIELD, including all parties who oversee the access to, sharing of, or the use of data, or who access or use its data.8

Conclusions

The VA has assembled a scientific enterprise dedicated to combating emerging infectious diseases and other threats to our patients. This enterprise has been modeled in its structure and oversight to support VA SHIELD. The establishment of a real-time biorepository and data procurement system linked to clinical samples is a bold step forward to address current and future challenges. Similarly, the integration and cooperation of multiple arms within the VA that transcend disciplines and boundaries promise to shepherd a new era of system-wide investigation. In the future, VA SHIELD will integrate with other existing government agencies to advance mutual scientific agendas. VA SHIELD has established the data and biorepository infrastructure to develop innovative and novel technologies to address future challenges. The alignment of basic science, clinical, and translational research goals under one governance is a significant advancement compared with previous models of research coordination.

VA SHIELD was developed to meet an immediate need; it was also framed to be a research enterprise that harnesses the robust clinical and research environment in VHA. The VA SHIELD infrastructure was conceptualized to harmonize specimen and data collection across the VA, allowing researchers to leverage broader collection efforts. Building a biorepository and data collection system within the largest integrated health care system has the potential to provide a lasting impact on VHA and on our nation’s health.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Daphne Swancutt for her contribution as copywriter for this manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge the VA SHIELD investigators: Mary Cloud Ammons, David Beenhouwer, Sheldon T. Brown, Victoria Davey, Abhinav Diwan, John B. Harley, Mark Holodniy, Vincent C. Marconi, Jonathan Moorman, Emerson B. Padiernos, Ian F. Robey, Maria Rodriguez-Barradas, Jason Wertheim, Christopher W. Woods.

1. Lipshy KA, Itani K, Chu D, et al. Sentinel contributions of US Department of Veterans Affairs surgeons in shaping the face of health care. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(4):380-386. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.6372

2. Zucker S, Crabbe JC, Cooper G 4th, et al. Veterans Administration support for medical research: opinions of the endangered species of physician-scientists. FASEB J. 2004;18(13):1481-1486. doi:10.1096/fj.04-1573lfe

3. Harley JB, Pyarajan S, Partan ES, et al. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD): a biorepository addressing national health threats. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac641. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac641

4. Meites E, Bajema KL, Kambhampati A, et al; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group. Adapting the Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (SUPERNOVA) for COVID-19 among hospitalized adults: surveillance protocol. Front Public Health. 2021;9:739076. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.739076

5. Bajema KL, Dahl RM, Evener SL, et al; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group; Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at the VA (SUPERNOVA) COVID-19 Surveillance Group. Comparative effectiveness and antibody responses to Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines among hospitalized veterans–five Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, United States, February 1-September 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(49):1700-1705. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7049a2external icon

6. Krishnan J, Woods C, Holodniy M, et al. Nationwide genomic surveillance and response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): SeqCURE and SeqFORCE consortiums. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S44-S47. doi:10.12788/fp.0417

7. Ashcroft JW, Macpherson CC. The complex ethical landscape of biobanking. Lancet Public Health. 2019;(6):e274-e275. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30081-7

8. Principle-Based Ethics Framework for Access to and Use of Veteran Data. Fed Regist. 2022;87(129):40451-40452.

1. Lipshy KA, Itani K, Chu D, et al. Sentinel contributions of US Department of Veterans Affairs surgeons in shaping the face of health care. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(4):380-386. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.6372

2. Zucker S, Crabbe JC, Cooper G 4th, et al. Veterans Administration support for medical research: opinions of the endangered species of physician-scientists. FASEB J. 2004;18(13):1481-1486. doi:10.1096/fj.04-1573lfe

3. Harley JB, Pyarajan S, Partan ES, et al. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD): a biorepository addressing national health threats. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac641. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac641

4. Meites E, Bajema KL, Kambhampati A, et al; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group. Adapting the Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (SUPERNOVA) for COVID-19 among hospitalized adults: surveillance protocol. Front Public Health. 2021;9:739076. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.739076

5. Bajema KL, Dahl RM, Evener SL, et al; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group; Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at the VA (SUPERNOVA) COVID-19 Surveillance Group. Comparative effectiveness and antibody responses to Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines among hospitalized veterans–five Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, United States, February 1-September 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(49):1700-1705. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7049a2external icon

6. Krishnan J, Woods C, Holodniy M, et al. Nationwide genomic surveillance and response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): SeqCURE and SeqFORCE consortiums. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S44-S47. doi:10.12788/fp.0417

7. Ashcroft JW, Macpherson CC. The complex ethical landscape of biobanking. Lancet Public Health. 2019;(6):e274-e275. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30081-7

8. Principle-Based Ethics Framework for Access to and Use of Veteran Data. Fed Regist. 2022;87(129):40451-40452.

Nationwide Genomic Surveillance and Response to COVID-19: The VA SeqFORCE and SeqCURE Consortiums

The COVID-19 virus and its associated pandemic have highlighted the urgent need for a national infrastructure to rapidly identify and respond to emerging pathogens. The importance of understanding viral population dynamics through genetic sequencing has become apparent over time, particularly as the vaccine responses, clinical implications, and therapeutic effectiveness of treatments have varied substantially with COVID-19 variants.1,2

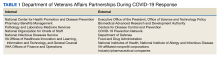

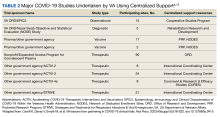

As the largest integrated health care system in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is uniquely situated to help with pandemic detection and response. This article highlights 2 VA programs dedicated to COVID-19 sequencing at the forefront of pandemic response and research: VA Sequencing for Research Clinical and Epidemiology (SeqFORCE) and VA Sequencing Collaborations United for Research and Epidemiology (SeqCURE) (Table).

VA Seq FORCE

VA SeqFORCE was established March 2021 to facilitate clinical surveillance of COVID-19 variants in the US veteran population and in VA employees. VA SeqFORCE consists of 9 Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)–certified laboratories in VA medical centers, including the VA Public Health Reference Laboratory in Palo Alto, California, and 8 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinical laboratories (Los Angeles, California; Boise, Idaho; Iowa City, Iowa; Bronx, New York; West Haven, Connecticut; Indianapolis, Indiana; Denver, Colorado; and Orlando, Florida).3 Specimen standards (eg, real-time polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] cycle threshold [Ct] ≤ 30, minimum volume, etc) and clinical criteria (eg, COVID-19–related deaths, COVID-19 vaccine escape, etc) for submitting samples to VA SeqFORCE laboratories were established, and logistics for sample sequencing was centralized, including providing centralized instructions for sample preparation and to which VA SeqFORCE laboratory samples should be sent.

These laboratories sequenced samples from patients and employees with COVID-19 to understand patterns of variant evolution, vaccine, antiviral and monoclonal antibody response, health care–associated outbreaks, and COVID-19 transmission. As clinically relevant findings, such as monoclonal antibody treatment failure, emerged with novel viral variants, VA SeqFORCE was well positioned to rapidly detect the emergent variants and inform better clinical care of patients with COVID-19. Other clinical indications identified for sequencing within VA SeqFORCE included outbreak investigation, re-infection with COVID-19 > 90 days but < 6 months after a prior infection, extended hospitalization of > 21 days, death due to COVID-19, infection with a history of recent nondomestic travel, rebound of symptoms after improvement on oral antiviral therapy, and epidemiologic surveillance.

VA SeqFORCE laboratories use a variety of sequencing platforms, although a federated system was developed that electronically linked all laboratories using a software system (PraediGene, Bitscopic) for sample management, COVID-19 variant analytics, and automated result reporting of clade and lineage into the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) Computerized Patient Record System. In addition, generated nucleic acid sequence alignment through FASTA consensus sequence files have been archived for secondary research analyses. By archiving the consensus sequences, retrospective studies within the VA have the added benefit of being able to clinically annotate investigations into COVID-19 variant patterns. As of August 2023, 43,003 samples containing COVID-19 have been sequenced, and FASTA file and metadata upload are ongoing to the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data, which houses > 15 million COVID-19 files from global submissions.

VA SeqFORCE’s clinical sequencing efforts have created opportunities for multicenter collaboration in variant surveillance. In work from December 2021, investigators from the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, New York, collaborated with the VHA Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services and Public Health national program offices in Washington, DC, to develop an RT-PCR assay to rapidly differentiate Omicron from Delta variants.4 Samples from VA hospitals across the nation were used in this study.

Lessons from VA SeqFORCE have also been cited as inspiration to address COVID-19 clinical problems, including outbreak investigations in hospital settings and beyond. Researchers at the Iowa City VA Health Care System, for example, proposed a novel probabilistic quantitative method for determining genetic-relatedness among COVID-19 viral strains in an outbreak setting.5 They extended the scope of work to develop COVID-19 outbreak screening tools combining publicly available algorithms with targeted sequencing data to identify outbreaks as they arise.6 We expect VA SeqFORCE, in conjunction with its complement VA SeqCURE, will continue to further pandemic surveillance and response.

VA Seq CURE

As the research-focused complement to VA SeqFORCE, VA SeqCURE is dedicated to a broader study of the COVID-19 genome through sequencing. Established January 2021, the VA SeqCURE network consists of 6 research laboratories in Boise, Idaho; Bronx, New York; Cleveland, Ohio; Durham, North Carolina; Iowa City, Iowa; and Temple, Texas.

Samples are collected as a subset of the broader VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD) biorepository sweep protocol for discarded blood and nasal swab specimens of VHA patients hospitalized with COVID-19, as described by Epstein and colleagues.7-9 While VA SeqFORCE sequences samples positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR with a Ct value of ≤ 30 for diagnostic purposes, VA SeqCURE laboratories sequence more broadly for nondiagnostic purposes, including samples with a Ct value > 30. The 6 VA SeqCURE laboratories generate sequencing data using various platforms, amplification kits, and formats. To ensure maximum quality and metadata on the sequences generated across the different laboratories, a sequence intake pipeline has been developed, adapting the ViralRecon bioinformatics platform.10 This harmonized analysis pipeline accommodates different file formats and performs quality control, alignment, variant calling, lineage assignment, clade assignment, and annotation. As of August 2023, VA SeqCURE has identified viral sequences from 24,107 unique specimens. Annotated COVID-19 sequences with the appropriate metadata will be available to VA researchers through VA SHIELD.

Research projects include descriptive epidemiology of COVID-19 variants in individuals who receive VHA care, COVID-19 vaccine and therapy effectiveness, and the unique distribution of variants and vaccine effectiveness in rural settings.3 True to its core mission, members of the VA SeqCURE consortium have contributed to the COVID-19 viral sequencing literature over the past 2 years. Researchers also are accessing VA SeqCURE to study COVID-19 persistence and rebound among individuals with mild disease taking nirmatrelvir/ritonavir compared with other COVID-19 therapeutics and untreated controls. Finally, COVID-19 samples and their sequences are stored in the VA SHIELD biorepository, which leverages these samples and data to advance scientific understanding of COVID-19 and future emerging infectious diseases.7-9

Important work from investigators at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System confronted the issue of whole genome sequencing data from COVID-19 samples with low viral loads, a common issue with COVID-19 sequencing. They found that yields of 2 sequencing protocols, which generated high-sequence coverage, were enhanced further by combining the results of both methods.11 This project, which has potentially broad applications for sequencing in research and clinical settings, is an example of VA SeqCURE’s efforts to address the COVID-19 pandemic. The VA SeqCURE program has substantial potential as a large viral sequencing repository with broad geographic and demographic representation, such that future large-scale sequencing analyses may be generated from preexisting nested cohorts within the repository.

NEXT STEPS

Promising new directions of clinical and laboratory-based research are planned for VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE. While the impact of COVID-19 and other viruses with epidemic potential is perhaps most feared in urban settings, evidence suggests that the distribution of COVID-19 in rural settings is unique and associated with worse outcomes.12,13 Given the wide catchment areas of VA hospitals that encompass both rural and urban settings, the VA’s ongoing COVID-19 sequencing programs and repositories are uniquely positioned to understand viral dynamics in areas of differing population density.

While rates of infection, hospitalization, and death resulting from COVID-19 have substantially dropped, the long-term impact of the pandemic is just beginning to be recognized in conditions such as long COVID or postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Long COVID has already proven to be biologically multifaceted, difficult to diagnose, and unpredictable in identifying the most at-risk patients.14-16 Much remains to be determined in our understanding of long COVID, including a unified definition that can effectively be used in clinical settings to diagnose and treat patients. However, research indicates that comorbidities common in veterans, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, are associated with worse long-term outcomes.17,18 Collaborations between VA scientists, clinicians, and national cooperative programs (such as a network of VHA long COVID clinics) create an unmatched opportunity for VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs to provide insight into a disease likely to become a chronic disease outcome of the pandemic.

With VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs, the VA now has infrastructure ready to respond to new infectious diseases. During the mpox outbreak of 2022, the VA Public Health Reference Laboratory received > 80% of all VA mpox samples for orthopox screening and mpox confirmatory testing. A subset of these samples underwent whole genome sequencing with the identification of 10 unique lineages across VA, and > 200 positive and 400 negative samples have been aliquoted and submitted to VA SHIELD for research. Furthermore, the VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE sequencing processes might be adapted to identify outbreaks of multidrug-resistant organisms among VA patients trialed at other institutions.19 We are hopeful that VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE will become invaluable components of health care delivery and infection prevention at the hospital level and beyond.

Finally, the robust data infrastructure and associated repositories of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE may be leveraged to study noninfectious diseases. Research groups are starting to apply these programs to cancer sequencing. We anticipate that these efforts may have a substantial impact on our understanding of cancer epidemiology and region-specific risk factors for malignancy, given the size and breadth of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE. Common oncogenic mutations identified through these programs could be targets for precision oncology therapeutics. Similarly, we envision applications of the VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE data infrastructures and repositories toward other precision medicine fields, including pharmacogenomics and nutrition, to tailor interventions to meet the specific individual needs of veterans.

CONCLUSIONS

The productivity of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs over the past 2 years continues to increase in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We anticipate that they will be vital components in our nation’s responses to infectious threats and beyond.

1. Iuliano AD, Brunkard JM, Boehmer TK, et al. Trends in disease severity and health care utilization during the early Omicron variant period compared with previous SARS-CoV-2 high transmission periods - United States, December 2020-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(4):146-152. Published 2022 Jan 28. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e4

2. Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303-1312. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7

3. Veterans Health Administration. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) response report - annex C. December 5, 2022. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/VHA-COVID-19-Response-2022-Annex-C.pdf 4. Barasch NJ, Iqbal J, Coombs M, et al. Utilization of a SARS-CoV-2 variant assay for the rapid differentiation of Omicron and Delta. medRxiv. Preprint posted online December 27, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.12.22.21268195

5. Bilal MY. Similarity Index-probabilistic confidence estimation of SARS-CoV-2 strain relatedness in localized outbreaks. Epidemiologia (Basel). 2022;3(2):238-249. doi:10.3390/epidemiologia3020019

6. Bilal MY, Klutts JS. Molecular Epidemiological investigations of localized SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks-utility of public algorithms. Epidemiologia (Basel). 2022;3(3):402-411. doi:10.3390/epidemiologia3030031

7. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research & Development. VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD). Updated November 23, 2022. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/programs/shield/about.cfm

8. Harley JB, Pyarajan S, Partan ES, et al. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD): a biorepository addressing national health threats. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac641. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac641

9. Epstein L, Shive C, Garcia AP, et al. VA SHIELD: a biorepository for our veterans and the nation. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S48-S51. doi:10.12788/fp.0424

10. Patel H, Varona S, Monzón S, et al. Version 2.5. nf-core/viralrecon: nf-core/viralrecon v2.5 - Manganese Monkey (2.5). Zenodo. July 13, 2022. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6827984

11. Choi H, Hwang M, Navarathna DH, Xu J, Lukey J, Jinadatha C. Performance of COVIDSeq and swift normalase amplicon SARS-CoV-2 panels for SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing: practical guide and combining FASTQ strategy. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60(4):e0002522. doi:10.1128/jcm.00025-22

12. Cuadros DF, Branscum AJ, Mukandavire Z, Miller FD, MacKinnon N. Dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in urban and rural areas in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;59:16-20. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.04.007

13. Anzalone AJ, Horswell R, Hendricks BM, et al. Higher hospitalization and mortality rates among SARS-CoV-2-infected persons in rural America. J Rural Health. 2023;39(1):39-54. doi:10.1111/jrh.12689

14. Su Y, Yuan D, Chen DG, et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. 2022;185(5):881-895.e20. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.014

15. Pfaff ER, Girvin AT, Bennett TD, et al. Identifying who has long COVID in the USA: a machine learning approach using N3C data. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(7):e532-e541. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00048-6

16. Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes S, et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1706-1714. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w

17. Munblit D, O’Hara ME, Akrami A, Perego E, Olliaro P, Needham DM. Long COVID: aiming for a consensus. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(7):632-634. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00135-7

18. Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, et al. Development of a definition of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2023;329(22):1934-1946. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.8823

19. Sundermann AJ, Chen J, Kumar P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing surveillance and machine learning of the electronic health record for enhanced healthcare outbreak detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(3):476-482. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab946

The COVID-19 virus and its associated pandemic have highlighted the urgent need for a national infrastructure to rapidly identify and respond to emerging pathogens. The importance of understanding viral population dynamics through genetic sequencing has become apparent over time, particularly as the vaccine responses, clinical implications, and therapeutic effectiveness of treatments have varied substantially with COVID-19 variants.1,2

As the largest integrated health care system in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is uniquely situated to help with pandemic detection and response. This article highlights 2 VA programs dedicated to COVID-19 sequencing at the forefront of pandemic response and research: VA Sequencing for Research Clinical and Epidemiology (SeqFORCE) and VA Sequencing Collaborations United for Research and Epidemiology (SeqCURE) (Table).

VA Seq FORCE

VA SeqFORCE was established March 2021 to facilitate clinical surveillance of COVID-19 variants in the US veteran population and in VA employees. VA SeqFORCE consists of 9 Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)–certified laboratories in VA medical centers, including the VA Public Health Reference Laboratory in Palo Alto, California, and 8 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinical laboratories (Los Angeles, California; Boise, Idaho; Iowa City, Iowa; Bronx, New York; West Haven, Connecticut; Indianapolis, Indiana; Denver, Colorado; and Orlando, Florida).3 Specimen standards (eg, real-time polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] cycle threshold [Ct] ≤ 30, minimum volume, etc) and clinical criteria (eg, COVID-19–related deaths, COVID-19 vaccine escape, etc) for submitting samples to VA SeqFORCE laboratories were established, and logistics for sample sequencing was centralized, including providing centralized instructions for sample preparation and to which VA SeqFORCE laboratory samples should be sent.

These laboratories sequenced samples from patients and employees with COVID-19 to understand patterns of variant evolution, vaccine, antiviral and monoclonal antibody response, health care–associated outbreaks, and COVID-19 transmission. As clinically relevant findings, such as monoclonal antibody treatment failure, emerged with novel viral variants, VA SeqFORCE was well positioned to rapidly detect the emergent variants and inform better clinical care of patients with COVID-19. Other clinical indications identified for sequencing within VA SeqFORCE included outbreak investigation, re-infection with COVID-19 > 90 days but < 6 months after a prior infection, extended hospitalization of > 21 days, death due to COVID-19, infection with a history of recent nondomestic travel, rebound of symptoms after improvement on oral antiviral therapy, and epidemiologic surveillance.

VA SeqFORCE laboratories use a variety of sequencing platforms, although a federated system was developed that electronically linked all laboratories using a software system (PraediGene, Bitscopic) for sample management, COVID-19 variant analytics, and automated result reporting of clade and lineage into the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) Computerized Patient Record System. In addition, generated nucleic acid sequence alignment through FASTA consensus sequence files have been archived for secondary research analyses. By archiving the consensus sequences, retrospective studies within the VA have the added benefit of being able to clinically annotate investigations into COVID-19 variant patterns. As of August 2023, 43,003 samples containing COVID-19 have been sequenced, and FASTA file and metadata upload are ongoing to the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data, which houses > 15 million COVID-19 files from global submissions.

VA SeqFORCE’s clinical sequencing efforts have created opportunities for multicenter collaboration in variant surveillance. In work from December 2021, investigators from the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, New York, collaborated with the VHA Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services and Public Health national program offices in Washington, DC, to develop an RT-PCR assay to rapidly differentiate Omicron from Delta variants.4 Samples from VA hospitals across the nation were used in this study.

Lessons from VA SeqFORCE have also been cited as inspiration to address COVID-19 clinical problems, including outbreak investigations in hospital settings and beyond. Researchers at the Iowa City VA Health Care System, for example, proposed a novel probabilistic quantitative method for determining genetic-relatedness among COVID-19 viral strains in an outbreak setting.5 They extended the scope of work to develop COVID-19 outbreak screening tools combining publicly available algorithms with targeted sequencing data to identify outbreaks as they arise.6 We expect VA SeqFORCE, in conjunction with its complement VA SeqCURE, will continue to further pandemic surveillance and response.

VA Seq CURE

As the research-focused complement to VA SeqFORCE, VA SeqCURE is dedicated to a broader study of the COVID-19 genome through sequencing. Established January 2021, the VA SeqCURE network consists of 6 research laboratories in Boise, Idaho; Bronx, New York; Cleveland, Ohio; Durham, North Carolina; Iowa City, Iowa; and Temple, Texas.

Samples are collected as a subset of the broader VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD) biorepository sweep protocol for discarded blood and nasal swab specimens of VHA patients hospitalized with COVID-19, as described by Epstein and colleagues.7-9 While VA SeqFORCE sequences samples positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR with a Ct value of ≤ 30 for diagnostic purposes, VA SeqCURE laboratories sequence more broadly for nondiagnostic purposes, including samples with a Ct value > 30. The 6 VA SeqCURE laboratories generate sequencing data using various platforms, amplification kits, and formats. To ensure maximum quality and metadata on the sequences generated across the different laboratories, a sequence intake pipeline has been developed, adapting the ViralRecon bioinformatics platform.10 This harmonized analysis pipeline accommodates different file formats and performs quality control, alignment, variant calling, lineage assignment, clade assignment, and annotation. As of August 2023, VA SeqCURE has identified viral sequences from 24,107 unique specimens. Annotated COVID-19 sequences with the appropriate metadata will be available to VA researchers through VA SHIELD.

Research projects include descriptive epidemiology of COVID-19 variants in individuals who receive VHA care, COVID-19 vaccine and therapy effectiveness, and the unique distribution of variants and vaccine effectiveness in rural settings.3 True to its core mission, members of the VA SeqCURE consortium have contributed to the COVID-19 viral sequencing literature over the past 2 years. Researchers also are accessing VA SeqCURE to study COVID-19 persistence and rebound among individuals with mild disease taking nirmatrelvir/ritonavir compared with other COVID-19 therapeutics and untreated controls. Finally, COVID-19 samples and their sequences are stored in the VA SHIELD biorepository, which leverages these samples and data to advance scientific understanding of COVID-19 and future emerging infectious diseases.7-9

Important work from investigators at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System confronted the issue of whole genome sequencing data from COVID-19 samples with low viral loads, a common issue with COVID-19 sequencing. They found that yields of 2 sequencing protocols, which generated high-sequence coverage, were enhanced further by combining the results of both methods.11 This project, which has potentially broad applications for sequencing in research and clinical settings, is an example of VA SeqCURE’s efforts to address the COVID-19 pandemic. The VA SeqCURE program has substantial potential as a large viral sequencing repository with broad geographic and demographic representation, such that future large-scale sequencing analyses may be generated from preexisting nested cohorts within the repository.

NEXT STEPS

Promising new directions of clinical and laboratory-based research are planned for VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE. While the impact of COVID-19 and other viruses with epidemic potential is perhaps most feared in urban settings, evidence suggests that the distribution of COVID-19 in rural settings is unique and associated with worse outcomes.12,13 Given the wide catchment areas of VA hospitals that encompass both rural and urban settings, the VA’s ongoing COVID-19 sequencing programs and repositories are uniquely positioned to understand viral dynamics in areas of differing population density.

While rates of infection, hospitalization, and death resulting from COVID-19 have substantially dropped, the long-term impact of the pandemic is just beginning to be recognized in conditions such as long COVID or postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Long COVID has already proven to be biologically multifaceted, difficult to diagnose, and unpredictable in identifying the most at-risk patients.14-16 Much remains to be determined in our understanding of long COVID, including a unified definition that can effectively be used in clinical settings to diagnose and treat patients. However, research indicates that comorbidities common in veterans, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, are associated with worse long-term outcomes.17,18 Collaborations between VA scientists, clinicians, and national cooperative programs (such as a network of VHA long COVID clinics) create an unmatched opportunity for VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs to provide insight into a disease likely to become a chronic disease outcome of the pandemic.

With VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs, the VA now has infrastructure ready to respond to new infectious diseases. During the mpox outbreak of 2022, the VA Public Health Reference Laboratory received > 80% of all VA mpox samples for orthopox screening and mpox confirmatory testing. A subset of these samples underwent whole genome sequencing with the identification of 10 unique lineages across VA, and > 200 positive and 400 negative samples have been aliquoted and submitted to VA SHIELD for research. Furthermore, the VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE sequencing processes might be adapted to identify outbreaks of multidrug-resistant organisms among VA patients trialed at other institutions.19 We are hopeful that VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE will become invaluable components of health care delivery and infection prevention at the hospital level and beyond.

Finally, the robust data infrastructure and associated repositories of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE may be leveraged to study noninfectious diseases. Research groups are starting to apply these programs to cancer sequencing. We anticipate that these efforts may have a substantial impact on our understanding of cancer epidemiology and region-specific risk factors for malignancy, given the size and breadth of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE. Common oncogenic mutations identified through these programs could be targets for precision oncology therapeutics. Similarly, we envision applications of the VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE data infrastructures and repositories toward other precision medicine fields, including pharmacogenomics and nutrition, to tailor interventions to meet the specific individual needs of veterans.

CONCLUSIONS

The productivity of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs over the past 2 years continues to increase in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We anticipate that they will be vital components in our nation’s responses to infectious threats and beyond.

The COVID-19 virus and its associated pandemic have highlighted the urgent need for a national infrastructure to rapidly identify and respond to emerging pathogens. The importance of understanding viral population dynamics through genetic sequencing has become apparent over time, particularly as the vaccine responses, clinical implications, and therapeutic effectiveness of treatments have varied substantially with COVID-19 variants.1,2

As the largest integrated health care system in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is uniquely situated to help with pandemic detection and response. This article highlights 2 VA programs dedicated to COVID-19 sequencing at the forefront of pandemic response and research: VA Sequencing for Research Clinical and Epidemiology (SeqFORCE) and VA Sequencing Collaborations United for Research and Epidemiology (SeqCURE) (Table).

VA Seq FORCE

VA SeqFORCE was established March 2021 to facilitate clinical surveillance of COVID-19 variants in the US veteran population and in VA employees. VA SeqFORCE consists of 9 Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)–certified laboratories in VA medical centers, including the VA Public Health Reference Laboratory in Palo Alto, California, and 8 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinical laboratories (Los Angeles, California; Boise, Idaho; Iowa City, Iowa; Bronx, New York; West Haven, Connecticut; Indianapolis, Indiana; Denver, Colorado; and Orlando, Florida).3 Specimen standards (eg, real-time polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR] cycle threshold [Ct] ≤ 30, minimum volume, etc) and clinical criteria (eg, COVID-19–related deaths, COVID-19 vaccine escape, etc) for submitting samples to VA SeqFORCE laboratories were established, and logistics for sample sequencing was centralized, including providing centralized instructions for sample preparation and to which VA SeqFORCE laboratory samples should be sent.

These laboratories sequenced samples from patients and employees with COVID-19 to understand patterns of variant evolution, vaccine, antiviral and monoclonal antibody response, health care–associated outbreaks, and COVID-19 transmission. As clinically relevant findings, such as monoclonal antibody treatment failure, emerged with novel viral variants, VA SeqFORCE was well positioned to rapidly detect the emergent variants and inform better clinical care of patients with COVID-19. Other clinical indications identified for sequencing within VA SeqFORCE included outbreak investigation, re-infection with COVID-19 > 90 days but < 6 months after a prior infection, extended hospitalization of > 21 days, death due to COVID-19, infection with a history of recent nondomestic travel, rebound of symptoms after improvement on oral antiviral therapy, and epidemiologic surveillance.

VA SeqFORCE laboratories use a variety of sequencing platforms, although a federated system was developed that electronically linked all laboratories using a software system (PraediGene, Bitscopic) for sample management, COVID-19 variant analytics, and automated result reporting of clade and lineage into the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) Computerized Patient Record System. In addition, generated nucleic acid sequence alignment through FASTA consensus sequence files have been archived for secondary research analyses. By archiving the consensus sequences, retrospective studies within the VA have the added benefit of being able to clinically annotate investigations into COVID-19 variant patterns. As of August 2023, 43,003 samples containing COVID-19 have been sequenced, and FASTA file and metadata upload are ongoing to the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data, which houses > 15 million COVID-19 files from global submissions.

VA SeqFORCE’s clinical sequencing efforts have created opportunities for multicenter collaboration in variant surveillance. In work from December 2021, investigators from the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, New York, collaborated with the VHA Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services and Public Health national program offices in Washington, DC, to develop an RT-PCR assay to rapidly differentiate Omicron from Delta variants.4 Samples from VA hospitals across the nation were used in this study.

Lessons from VA SeqFORCE have also been cited as inspiration to address COVID-19 clinical problems, including outbreak investigations in hospital settings and beyond. Researchers at the Iowa City VA Health Care System, for example, proposed a novel probabilistic quantitative method for determining genetic-relatedness among COVID-19 viral strains in an outbreak setting.5 They extended the scope of work to develop COVID-19 outbreak screening tools combining publicly available algorithms with targeted sequencing data to identify outbreaks as they arise.6 We expect VA SeqFORCE, in conjunction with its complement VA SeqCURE, will continue to further pandemic surveillance and response.

VA Seq CURE

As the research-focused complement to VA SeqFORCE, VA SeqCURE is dedicated to a broader study of the COVID-19 genome through sequencing. Established January 2021, the VA SeqCURE network consists of 6 research laboratories in Boise, Idaho; Bronx, New York; Cleveland, Ohio; Durham, North Carolina; Iowa City, Iowa; and Temple, Texas.

Samples are collected as a subset of the broader VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD) biorepository sweep protocol for discarded blood and nasal swab specimens of VHA patients hospitalized with COVID-19, as described by Epstein and colleagues.7-9 While VA SeqFORCE sequences samples positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR with a Ct value of ≤ 30 for diagnostic purposes, VA SeqCURE laboratories sequence more broadly for nondiagnostic purposes, including samples with a Ct value > 30. The 6 VA SeqCURE laboratories generate sequencing data using various platforms, amplification kits, and formats. To ensure maximum quality and metadata on the sequences generated across the different laboratories, a sequence intake pipeline has been developed, adapting the ViralRecon bioinformatics platform.10 This harmonized analysis pipeline accommodates different file formats and performs quality control, alignment, variant calling, lineage assignment, clade assignment, and annotation. As of August 2023, VA SeqCURE has identified viral sequences from 24,107 unique specimens. Annotated COVID-19 sequences with the appropriate metadata will be available to VA researchers through VA SHIELD.

Research projects include descriptive epidemiology of COVID-19 variants in individuals who receive VHA care, COVID-19 vaccine and therapy effectiveness, and the unique distribution of variants and vaccine effectiveness in rural settings.3 True to its core mission, members of the VA SeqCURE consortium have contributed to the COVID-19 viral sequencing literature over the past 2 years. Researchers also are accessing VA SeqCURE to study COVID-19 persistence and rebound among individuals with mild disease taking nirmatrelvir/ritonavir compared with other COVID-19 therapeutics and untreated controls. Finally, COVID-19 samples and their sequences are stored in the VA SHIELD biorepository, which leverages these samples and data to advance scientific understanding of COVID-19 and future emerging infectious diseases.7-9

Important work from investigators at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System confronted the issue of whole genome sequencing data from COVID-19 samples with low viral loads, a common issue with COVID-19 sequencing. They found that yields of 2 sequencing protocols, which generated high-sequence coverage, were enhanced further by combining the results of both methods.11 This project, which has potentially broad applications for sequencing in research and clinical settings, is an example of VA SeqCURE’s efforts to address the COVID-19 pandemic. The VA SeqCURE program has substantial potential as a large viral sequencing repository with broad geographic and demographic representation, such that future large-scale sequencing analyses may be generated from preexisting nested cohorts within the repository.

NEXT STEPS

Promising new directions of clinical and laboratory-based research are planned for VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE. While the impact of COVID-19 and other viruses with epidemic potential is perhaps most feared in urban settings, evidence suggests that the distribution of COVID-19 in rural settings is unique and associated with worse outcomes.12,13 Given the wide catchment areas of VA hospitals that encompass both rural and urban settings, the VA’s ongoing COVID-19 sequencing programs and repositories are uniquely positioned to understand viral dynamics in areas of differing population density.

While rates of infection, hospitalization, and death resulting from COVID-19 have substantially dropped, the long-term impact of the pandemic is just beginning to be recognized in conditions such as long COVID or postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Long COVID has already proven to be biologically multifaceted, difficult to diagnose, and unpredictable in identifying the most at-risk patients.14-16 Much remains to be determined in our understanding of long COVID, including a unified definition that can effectively be used in clinical settings to diagnose and treat patients. However, research indicates that comorbidities common in veterans, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, are associated with worse long-term outcomes.17,18 Collaborations between VA scientists, clinicians, and national cooperative programs (such as a network of VHA long COVID clinics) create an unmatched opportunity for VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs to provide insight into a disease likely to become a chronic disease outcome of the pandemic.

With VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs, the VA now has infrastructure ready to respond to new infectious diseases. During the mpox outbreak of 2022, the VA Public Health Reference Laboratory received > 80% of all VA mpox samples for orthopox screening and mpox confirmatory testing. A subset of these samples underwent whole genome sequencing with the identification of 10 unique lineages across VA, and > 200 positive and 400 negative samples have been aliquoted and submitted to VA SHIELD for research. Furthermore, the VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE sequencing processes might be adapted to identify outbreaks of multidrug-resistant organisms among VA patients trialed at other institutions.19 We are hopeful that VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE will become invaluable components of health care delivery and infection prevention at the hospital level and beyond.

Finally, the robust data infrastructure and associated repositories of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE may be leveraged to study noninfectious diseases. Research groups are starting to apply these programs to cancer sequencing. We anticipate that these efforts may have a substantial impact on our understanding of cancer epidemiology and region-specific risk factors for malignancy, given the size and breadth of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE. Common oncogenic mutations identified through these programs could be targets for precision oncology therapeutics. Similarly, we envision applications of the VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE data infrastructures and repositories toward other precision medicine fields, including pharmacogenomics and nutrition, to tailor interventions to meet the specific individual needs of veterans.

CONCLUSIONS

The productivity of VA SeqFORCE and VA SeqCURE programs over the past 2 years continues to increase in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We anticipate that they will be vital components in our nation’s responses to infectious threats and beyond.

1. Iuliano AD, Brunkard JM, Boehmer TK, et al. Trends in disease severity and health care utilization during the early Omicron variant period compared with previous SARS-CoV-2 high transmission periods - United States, December 2020-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(4):146-152. Published 2022 Jan 28. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e4

2. Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303-1312. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7

3. Veterans Health Administration. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) response report - annex C. December 5, 2022. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/VHA-COVID-19-Response-2022-Annex-C.pdf 4. Barasch NJ, Iqbal J, Coombs M, et al. Utilization of a SARS-CoV-2 variant assay for the rapid differentiation of Omicron and Delta. medRxiv. Preprint posted online December 27, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.12.22.21268195

5. Bilal MY. Similarity Index-probabilistic confidence estimation of SARS-CoV-2 strain relatedness in localized outbreaks. Epidemiologia (Basel). 2022;3(2):238-249. doi:10.3390/epidemiologia3020019

6. Bilal MY, Klutts JS. Molecular Epidemiological investigations of localized SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks-utility of public algorithms. Epidemiologia (Basel). 2022;3(3):402-411. doi:10.3390/epidemiologia3030031

7. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research & Development. VA Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD). Updated November 23, 2022. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/programs/shield/about.cfm

8. Harley JB, Pyarajan S, Partan ES, et al. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Science and Health Initiative to Combat Infectious and Emerging Life-Threatening Diseases (VA SHIELD): a biorepository addressing national health threats. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac641. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac641