User login

Aerospace medicine and psychiatry

As part of my psychiatry residency training, I had the privilege to work with and learn from an aerospace psychiatrist. Aerospace medicine is a branch of preventive and occupational medicine in which aviators (pilots, aircrew, or astronauts) are subject to evaluation/treatment. The goal is to assess physical and mental health factors to mitigate risks, protect public safety, and ensure the aviators’ well-being.1,2 Aerospace psychiatry is a highly specialized area in which practitioners are trained to perform specific evaluations. In this article, I review those evaluations for those looking to gain insight into the field.

Aviation medical examination

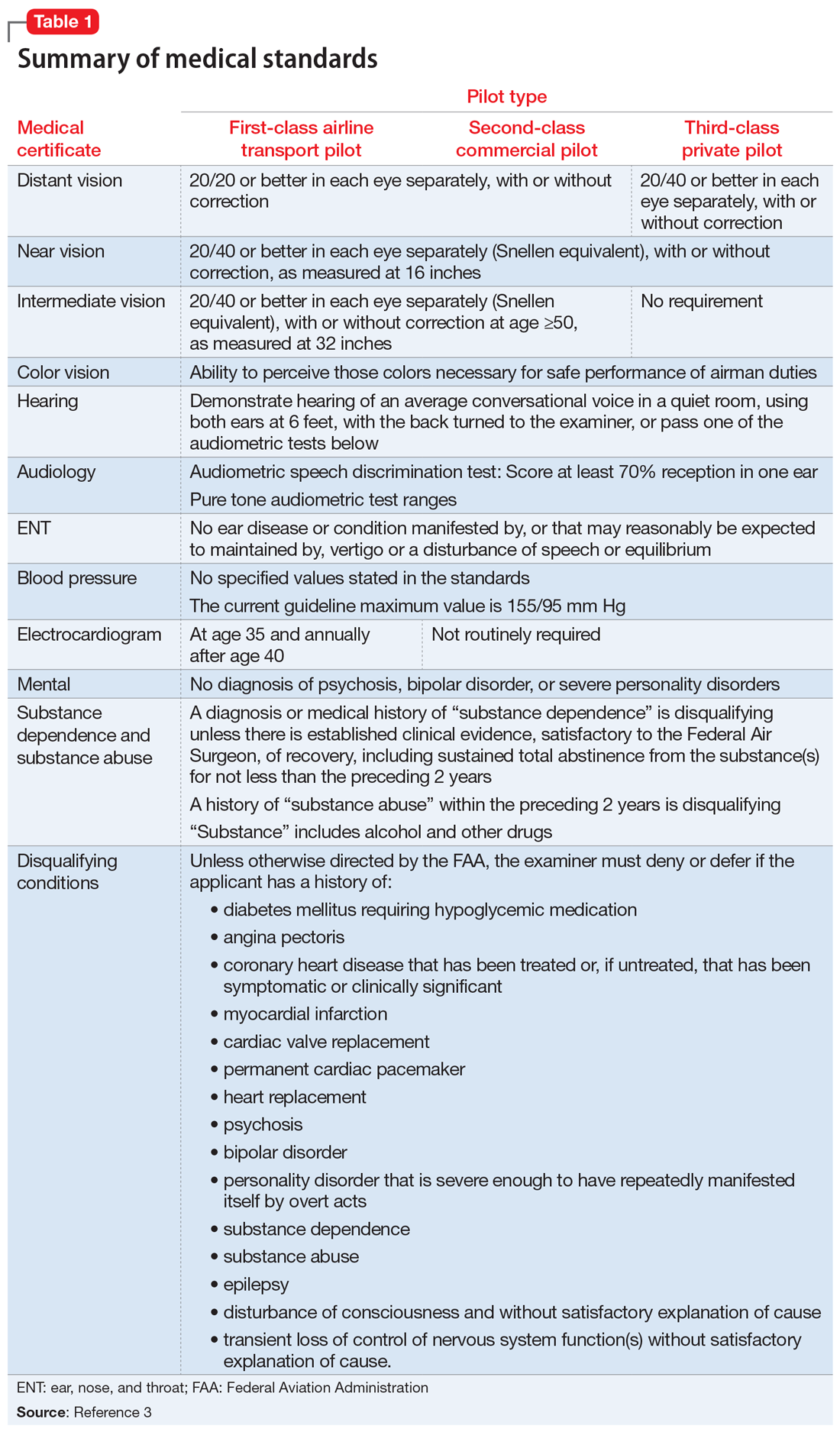

Under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) requires aviators to be evaluated for medical certification by undergoing an aviation medical exam.2 In order to be deemed “fit for duty,” aviators must meet strict physical and mental health standards set by the FAA. The extent of these standards varies by the class of licensure (Table 13). Aviation medical exams are performed by any physician who has been designated by the FAA and completed the appropriate FAA aviation medical examiner (AME) training. Aviators who meet the medical standards for their licensure class are recommended for medical certification. If the AME brings up further questions due to the limits of the examination and/or a lack of medical records, the certification will likely be deferred pending further evaluation by an FAA-approved medical specialist and/or the receipt of additional medical records. Questions about a possible psychiatric diagnosis/history or substance use disorder will lead to referral to a psychiatrist familiar with aviation standards for further evaluation.

_

Special issuances and Conditions AMEs Can Issue

There are 15 disqualifying conditions for medical certification (Table 13). However, a special issuance of a medical certification may be granted if the aviator shows to the satisfaction of the aviation medical examiner that the duties of the licensure class can be performed without endangering the public safety and that the condition is deemed stable. This may be shown through additional medical evaluations/tests and/or records.

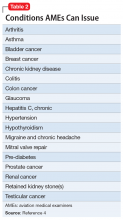

There are certain medical conditions for which an AME can issue a medical certificate without further review from other specialists; thus, an AME can review and follow the Conditions AMEs Can Issue (CACI) worksheet to recommend medical certification (Table 24). The CACI guidelines and worksheets are updated by the FAA regularly to ensure aviators’ health and minimize public risk.

Psychiatric & Psychological Evaluation

Aviators may be referred for Psychiatric and Psychological Evaluation (P&P) if an AME discovers additional concerns about psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders. These cases are not clear-cut. An example would be an aviator who was receiving a psychotropic medication in the past and reported past heavy alcohol use. The P&P includes a thorough psychiatric evaluation by an aerospace psychiatrist and extensive psychological testing by an aerospace psychologist. These clinicians also review collateral information and past medical/AME records. Aviators may be recommended for medical certification with special issuance or may be denied medical certification as a result of these examinations.

Human Intervention Motivation Study program

The Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS) program was established to provide an avenue whereby commercial pilots with active substance use disorders can be identified, treated, and successfully returned to active flight status.5 The goal of the HIMS program is to save lives and careers while enhancing flight safety. Physicians trained in HIMS evaluations follow the multifactorial addiction disease model. This evaluation is used to identify active substance use and initiate treatment, and to maintain sobriety and monitor aftercare adherence.

1. Bor R, Hubbard T. Aviation mental health: psychological implications for air transportation. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2006.

2. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Medical certification. https://www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/medical_certification/. Updated February 1, 2019. Accessed February 19, 2019.

3. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Summary of medical standards. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/media/synopsis.pdf. Revised April 3, 2006. Accessed October 7, 2018.

4. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Guide for aviation medical examiners: CACI conditions. Revised April 3, 2006. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/certification_ws/. Accessed October 8, 2018.

5. HIMS. About HIMS. http://www.himsprogram.com/Home/About. Accessed February 6, 2019.

As part of my psychiatry residency training, I had the privilege to work with and learn from an aerospace psychiatrist. Aerospace medicine is a branch of preventive and occupational medicine in which aviators (pilots, aircrew, or astronauts) are subject to evaluation/treatment. The goal is to assess physical and mental health factors to mitigate risks, protect public safety, and ensure the aviators’ well-being.1,2 Aerospace psychiatry is a highly specialized area in which practitioners are trained to perform specific evaluations. In this article, I review those evaluations for those looking to gain insight into the field.

Aviation medical examination

Under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) requires aviators to be evaluated for medical certification by undergoing an aviation medical exam.2 In order to be deemed “fit for duty,” aviators must meet strict physical and mental health standards set by the FAA. The extent of these standards varies by the class of licensure (Table 13). Aviation medical exams are performed by any physician who has been designated by the FAA and completed the appropriate FAA aviation medical examiner (AME) training. Aviators who meet the medical standards for their licensure class are recommended for medical certification. If the AME brings up further questions due to the limits of the examination and/or a lack of medical records, the certification will likely be deferred pending further evaluation by an FAA-approved medical specialist and/or the receipt of additional medical records. Questions about a possible psychiatric diagnosis/history or substance use disorder will lead to referral to a psychiatrist familiar with aviation standards for further evaluation.

_

Special issuances and Conditions AMEs Can Issue

There are 15 disqualifying conditions for medical certification (Table 13). However, a special issuance of a medical certification may be granted if the aviator shows to the satisfaction of the aviation medical examiner that the duties of the licensure class can be performed without endangering the public safety and that the condition is deemed stable. This may be shown through additional medical evaluations/tests and/or records.

There are certain medical conditions for which an AME can issue a medical certificate without further review from other specialists; thus, an AME can review and follow the Conditions AMEs Can Issue (CACI) worksheet to recommend medical certification (Table 24). The CACI guidelines and worksheets are updated by the FAA regularly to ensure aviators’ health and minimize public risk.

Psychiatric & Psychological Evaluation

Aviators may be referred for Psychiatric and Psychological Evaluation (P&P) if an AME discovers additional concerns about psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders. These cases are not clear-cut. An example would be an aviator who was receiving a psychotropic medication in the past and reported past heavy alcohol use. The P&P includes a thorough psychiatric evaluation by an aerospace psychiatrist and extensive psychological testing by an aerospace psychologist. These clinicians also review collateral information and past medical/AME records. Aviators may be recommended for medical certification with special issuance or may be denied medical certification as a result of these examinations.

Human Intervention Motivation Study program

The Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS) program was established to provide an avenue whereby commercial pilots with active substance use disorders can be identified, treated, and successfully returned to active flight status.5 The goal of the HIMS program is to save lives and careers while enhancing flight safety. Physicians trained in HIMS evaluations follow the multifactorial addiction disease model. This evaluation is used to identify active substance use and initiate treatment, and to maintain sobriety and monitor aftercare adherence.

As part of my psychiatry residency training, I had the privilege to work with and learn from an aerospace psychiatrist. Aerospace medicine is a branch of preventive and occupational medicine in which aviators (pilots, aircrew, or astronauts) are subject to evaluation/treatment. The goal is to assess physical and mental health factors to mitigate risks, protect public safety, and ensure the aviators’ well-being.1,2 Aerospace psychiatry is a highly specialized area in which practitioners are trained to perform specific evaluations. In this article, I review those evaluations for those looking to gain insight into the field.

Aviation medical examination

Under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) requires aviators to be evaluated for medical certification by undergoing an aviation medical exam.2 In order to be deemed “fit for duty,” aviators must meet strict physical and mental health standards set by the FAA. The extent of these standards varies by the class of licensure (Table 13). Aviation medical exams are performed by any physician who has been designated by the FAA and completed the appropriate FAA aviation medical examiner (AME) training. Aviators who meet the medical standards for their licensure class are recommended for medical certification. If the AME brings up further questions due to the limits of the examination and/or a lack of medical records, the certification will likely be deferred pending further evaluation by an FAA-approved medical specialist and/or the receipt of additional medical records. Questions about a possible psychiatric diagnosis/history or substance use disorder will lead to referral to a psychiatrist familiar with aviation standards for further evaluation.

_

Special issuances and Conditions AMEs Can Issue

There are 15 disqualifying conditions for medical certification (Table 13). However, a special issuance of a medical certification may be granted if the aviator shows to the satisfaction of the aviation medical examiner that the duties of the licensure class can be performed without endangering the public safety and that the condition is deemed stable. This may be shown through additional medical evaluations/tests and/or records.

There are certain medical conditions for which an AME can issue a medical certificate without further review from other specialists; thus, an AME can review and follow the Conditions AMEs Can Issue (CACI) worksheet to recommend medical certification (Table 24). The CACI guidelines and worksheets are updated by the FAA regularly to ensure aviators’ health and minimize public risk.

Psychiatric & Psychological Evaluation

Aviators may be referred for Psychiatric and Psychological Evaluation (P&P) if an AME discovers additional concerns about psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders. These cases are not clear-cut. An example would be an aviator who was receiving a psychotropic medication in the past and reported past heavy alcohol use. The P&P includes a thorough psychiatric evaluation by an aerospace psychiatrist and extensive psychological testing by an aerospace psychologist. These clinicians also review collateral information and past medical/AME records. Aviators may be recommended for medical certification with special issuance or may be denied medical certification as a result of these examinations.

Human Intervention Motivation Study program

The Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS) program was established to provide an avenue whereby commercial pilots with active substance use disorders can be identified, treated, and successfully returned to active flight status.5 The goal of the HIMS program is to save lives and careers while enhancing flight safety. Physicians trained in HIMS evaluations follow the multifactorial addiction disease model. This evaluation is used to identify active substance use and initiate treatment, and to maintain sobriety and monitor aftercare adherence.

1. Bor R, Hubbard T. Aviation mental health: psychological implications for air transportation. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2006.

2. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Medical certification. https://www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/medical_certification/. Updated February 1, 2019. Accessed February 19, 2019.

3. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Summary of medical standards. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/media/synopsis.pdf. Revised April 3, 2006. Accessed October 7, 2018.

4. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Guide for aviation medical examiners: CACI conditions. Revised April 3, 2006. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/certification_ws/. Accessed October 8, 2018.

5. HIMS. About HIMS. http://www.himsprogram.com/Home/About. Accessed February 6, 2019.

1. Bor R, Hubbard T. Aviation mental health: psychological implications for air transportation. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2006.

2. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Medical certification. https://www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/medical_certification/. Updated February 1, 2019. Accessed February 19, 2019.

3. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Summary of medical standards. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/media/synopsis.pdf. Revised April 3, 2006. Accessed October 7, 2018.

4. US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. Guide for aviation medical examiners: CACI conditions. Revised April 3, 2006. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/certification_ws/. Accessed October 8, 2018.

5. HIMS. About HIMS. http://www.himsprogram.com/Home/About. Accessed February 6, 2019.

Lessons learned working in the clinical trial industry

As a resident in psychiatry, I am being trained in the art of diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness and emotional problems. As part of my training, research and scholarly activities are encouraged—reminding us that clinical medicine is always evolving and that it is every physician’s duty to be at the forefront of advancements in medical science.

Last year, I worked in the clinical trial industry under a seasoned principal investigator. I learned several lessons from my time with him and in the industry. Here, I present these lessons as a starting point for residents who are looking to gain experience or contemplating a career as an expert trialist or principal investigator.

Lesson 1: Know the lingo

To make the transition from physician to principal investigator go more smoothly, I recommend taking the time to learn the language of the industry. The good news? Clinical trials involve patients who have a medical history and take medications, which you are well acquainted with. In addition to medical jargon, the industry has developed its own distinctive terminology and abbreviations: adverse drug reaction (ADR), good clinical practice (GCP), contract research organization (CRO), and more.

Don’t stop there, however. I recommend that you read FDA research guidelines and guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) to be familiar with the ethics and standard regulations of the industry.

Lesson 2: When in doubt, refer to the Protocol

Every clinical trial has a manual, so to speak, known as the Study Protocol, which outlines approved methods of performing diagnostic tests and procedures; provides information on the study timeline; and specifies patient inclusion and exclusion criteria. This document ensures conformity across all study sites, helps prevent errors, limits bias, and answers questions that might come up during the study. It’s worth noting that, in my experience, many of the questions about exclusionary medications arise when psychiatric drugs are involved.

Lesson 3: Document. Document. And document.

The golden rule in clinical practice and research is: “If it isn’t documented, it didn’t happen.” (Recall what I said about reading FDA and ICH-GCP guidelines to learn about regulations.) Documentation of all study-related activities must be meticulous. At any time, your documents might be subject to external or internal audit, conducted to preserve conformity to the protocol and maintain patient safety. Improper documentation can delay, even invalidate, your research.

Lesson 4: Remember that advertising is an art

The real work begins when your site is ready to accept patients. To fill the study, patients need to be aware that you are recruiting participants. A good starting point is to inform likely candidates from your existing patient population about any studies from which they might benefit.

Most times, however, recruiting among your patients is not enough to meet necessary enrollment numbers. You will have to advertise the study to the general public. Advertisements must target the specific patient population, informing them of the study but, at the same time, not be coercive or make false promises. The advertisements must be approved by the study’s institutional review board, which is responsible for protecting the rights and welfare of study participants.

Advertising can be tricky. If an advertisement is too vague, you will get a huge response, causing time and resources to be spent screening patients—most of whom might not be suitable for the study. If an advertisement is too specific, on the other hand, the response might be poor or none at all.

Advertising is its own industry. It might be best to hire an advertising expert who can help you decide on the selection of media (radio, television, print, digital) and can design a campaign that best suits your needs. If you decide to hire a professional, I recommend close collaboration with him (her), to help him understand the medical nature of the study.

Related Resources

• ClinicalTrials.gov. About clinical studies. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/about-studies.

• U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Clinical trials and human subject protection. http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/RunningClinicalTrials/default.htm.

• ICH GCP. International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. http://ichgcp.net/.

As a resident in psychiatry, I am being trained in the art of diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness and emotional problems. As part of my training, research and scholarly activities are encouraged—reminding us that clinical medicine is always evolving and that it is every physician’s duty to be at the forefront of advancements in medical science.

Last year, I worked in the clinical trial industry under a seasoned principal investigator. I learned several lessons from my time with him and in the industry. Here, I present these lessons as a starting point for residents who are looking to gain experience or contemplating a career as an expert trialist or principal investigator.

Lesson 1: Know the lingo

To make the transition from physician to principal investigator go more smoothly, I recommend taking the time to learn the language of the industry. The good news? Clinical trials involve patients who have a medical history and take medications, which you are well acquainted with. In addition to medical jargon, the industry has developed its own distinctive terminology and abbreviations: adverse drug reaction (ADR), good clinical practice (GCP), contract research organization (CRO), and more.

Don’t stop there, however. I recommend that you read FDA research guidelines and guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) to be familiar with the ethics and standard regulations of the industry.

Lesson 2: When in doubt, refer to the Protocol

Every clinical trial has a manual, so to speak, known as the Study Protocol, which outlines approved methods of performing diagnostic tests and procedures; provides information on the study timeline; and specifies patient inclusion and exclusion criteria. This document ensures conformity across all study sites, helps prevent errors, limits bias, and answers questions that might come up during the study. It’s worth noting that, in my experience, many of the questions about exclusionary medications arise when psychiatric drugs are involved.

Lesson 3: Document. Document. And document.

The golden rule in clinical practice and research is: “If it isn’t documented, it didn’t happen.” (Recall what I said about reading FDA and ICH-GCP guidelines to learn about regulations.) Documentation of all study-related activities must be meticulous. At any time, your documents might be subject to external or internal audit, conducted to preserve conformity to the protocol and maintain patient safety. Improper documentation can delay, even invalidate, your research.

Lesson 4: Remember that advertising is an art

The real work begins when your site is ready to accept patients. To fill the study, patients need to be aware that you are recruiting participants. A good starting point is to inform likely candidates from your existing patient population about any studies from which they might benefit.

Most times, however, recruiting among your patients is not enough to meet necessary enrollment numbers. You will have to advertise the study to the general public. Advertisements must target the specific patient population, informing them of the study but, at the same time, not be coercive or make false promises. The advertisements must be approved by the study’s institutional review board, which is responsible for protecting the rights and welfare of study participants.

Advertising can be tricky. If an advertisement is too vague, you will get a huge response, causing time and resources to be spent screening patients—most of whom might not be suitable for the study. If an advertisement is too specific, on the other hand, the response might be poor or none at all.

Advertising is its own industry. It might be best to hire an advertising expert who can help you decide on the selection of media (radio, television, print, digital) and can design a campaign that best suits your needs. If you decide to hire a professional, I recommend close collaboration with him (her), to help him understand the medical nature of the study.

Related Resources

• ClinicalTrials.gov. About clinical studies. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/about-studies.

• U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Clinical trials and human subject protection. http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/RunningClinicalTrials/default.htm.

• ICH GCP. International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. http://ichgcp.net/.

As a resident in psychiatry, I am being trained in the art of diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness and emotional problems. As part of my training, research and scholarly activities are encouraged—reminding us that clinical medicine is always evolving and that it is every physician’s duty to be at the forefront of advancements in medical science.

Last year, I worked in the clinical trial industry under a seasoned principal investigator. I learned several lessons from my time with him and in the industry. Here, I present these lessons as a starting point for residents who are looking to gain experience or contemplating a career as an expert trialist or principal investigator.

Lesson 1: Know the lingo

To make the transition from physician to principal investigator go more smoothly, I recommend taking the time to learn the language of the industry. The good news? Clinical trials involve patients who have a medical history and take medications, which you are well acquainted with. In addition to medical jargon, the industry has developed its own distinctive terminology and abbreviations: adverse drug reaction (ADR), good clinical practice (GCP), contract research organization (CRO), and more.

Don’t stop there, however. I recommend that you read FDA research guidelines and guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) to be familiar with the ethics and standard regulations of the industry.

Lesson 2: When in doubt, refer to the Protocol

Every clinical trial has a manual, so to speak, known as the Study Protocol, which outlines approved methods of performing diagnostic tests and procedures; provides information on the study timeline; and specifies patient inclusion and exclusion criteria. This document ensures conformity across all study sites, helps prevent errors, limits bias, and answers questions that might come up during the study. It’s worth noting that, in my experience, many of the questions about exclusionary medications arise when psychiatric drugs are involved.

Lesson 3: Document. Document. And document.

The golden rule in clinical practice and research is: “If it isn’t documented, it didn’t happen.” (Recall what I said about reading FDA and ICH-GCP guidelines to learn about regulations.) Documentation of all study-related activities must be meticulous. At any time, your documents might be subject to external or internal audit, conducted to preserve conformity to the protocol and maintain patient safety. Improper documentation can delay, even invalidate, your research.

Lesson 4: Remember that advertising is an art

The real work begins when your site is ready to accept patients. To fill the study, patients need to be aware that you are recruiting participants. A good starting point is to inform likely candidates from your existing patient population about any studies from which they might benefit.

Most times, however, recruiting among your patients is not enough to meet necessary enrollment numbers. You will have to advertise the study to the general public. Advertisements must target the specific patient population, informing them of the study but, at the same time, not be coercive or make false promises. The advertisements must be approved by the study’s institutional review board, which is responsible for protecting the rights and welfare of study participants.

Advertising can be tricky. If an advertisement is too vague, you will get a huge response, causing time and resources to be spent screening patients—most of whom might not be suitable for the study. If an advertisement is too specific, on the other hand, the response might be poor or none at all.

Advertising is its own industry. It might be best to hire an advertising expert who can help you decide on the selection of media (radio, television, print, digital) and can design a campaign that best suits your needs. If you decide to hire a professional, I recommend close collaboration with him (her), to help him understand the medical nature of the study.

Related Resources

• ClinicalTrials.gov. About clinical studies. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/about-studies.

• U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Clinical trials and human subject protection. http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/RunningClinicalTrials/default.htm.

• ICH GCP. International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. http://ichgcp.net/.