User login

Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Older (Age ≥ 80) Veterans With Newly Diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Background

Over one-third of newly diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cases are in people age ≥75. Although a potentially curable malignancy, older adults have a comparatively lower survival rate. This may be due to multiple factors including suboptimal management. In one study, up to 23% of patients age ≥80 did not receive any therapy for DLBCL. This age-related survival disparity is potentially magnified in patients who reside in rural areas. As there is no standard of care for this population, we speculate that there is wide variation in treatment practices which may influence outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe treatment patterns and outcomes in in veterans age ≥80 with DLBCL by area of residence.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of veterans age ≥80 newly diagnosed with Stage II-IV DLBCL between 2006-2023 using the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System (VACRS). Patient, disease, and treatment variables were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and via chart review. Variables were compared amongst Veterans residing at urban vs. rural addresses.

Results

We evaluated a total of 181 Veterans. Most veterans resided in an urban area (60.2%). At least 18.8% of veterans failed to start lymphoma-directed therapy, but only 6.6% of veterans were not explicitly offered treatment per documentation. In total, 68.5% of veterans were offered a curative treatment regimen by their provider; curative treatment was more likely to be offered to urban patients (68.8% vs 61.5%, p=0.86). Pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments prior to treatment were severely underutilized (2.8% and 0.6%). More urban veterans started treatment (75.2% vs 65.4%, p=0.38) and 40.9% started an anthracyclinecontaining regimen. Only 27.6% of veterans completed 6 total cycles of treatment. Only 37.6% of veterans achieved a complete response at end of treatment, although response was not reported in 46.4% of patients.

Conclusions

Most elderly veterans with DLBCL are being offered and started on a curative treatment regimen; however, most do not complete a full course of treatment. Although not statistically significant, more urban veterans were offered a curative regimen and received treatment. Wider adoption of pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments could improve response outcomes.

Background

Over one-third of newly diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cases are in people age ≥75. Although a potentially curable malignancy, older adults have a comparatively lower survival rate. This may be due to multiple factors including suboptimal management. In one study, up to 23% of patients age ≥80 did not receive any therapy for DLBCL. This age-related survival disparity is potentially magnified in patients who reside in rural areas. As there is no standard of care for this population, we speculate that there is wide variation in treatment practices which may influence outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe treatment patterns and outcomes in in veterans age ≥80 with DLBCL by area of residence.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of veterans age ≥80 newly diagnosed with Stage II-IV DLBCL between 2006-2023 using the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System (VACRS). Patient, disease, and treatment variables were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and via chart review. Variables were compared amongst Veterans residing at urban vs. rural addresses.

Results

We evaluated a total of 181 Veterans. Most veterans resided in an urban area (60.2%). At least 18.8% of veterans failed to start lymphoma-directed therapy, but only 6.6% of veterans were not explicitly offered treatment per documentation. In total, 68.5% of veterans were offered a curative treatment regimen by their provider; curative treatment was more likely to be offered to urban patients (68.8% vs 61.5%, p=0.86). Pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments prior to treatment were severely underutilized (2.8% and 0.6%). More urban veterans started treatment (75.2% vs 65.4%, p=0.38) and 40.9% started an anthracyclinecontaining regimen. Only 27.6% of veterans completed 6 total cycles of treatment. Only 37.6% of veterans achieved a complete response at end of treatment, although response was not reported in 46.4% of patients.

Conclusions

Most elderly veterans with DLBCL are being offered and started on a curative treatment regimen; however, most do not complete a full course of treatment. Although not statistically significant, more urban veterans were offered a curative regimen and received treatment. Wider adoption of pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments could improve response outcomes.

Background

Over one-third of newly diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cases are in people age ≥75. Although a potentially curable malignancy, older adults have a comparatively lower survival rate. This may be due to multiple factors including suboptimal management. In one study, up to 23% of patients age ≥80 did not receive any therapy for DLBCL. This age-related survival disparity is potentially magnified in patients who reside in rural areas. As there is no standard of care for this population, we speculate that there is wide variation in treatment practices which may influence outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe treatment patterns and outcomes in in veterans age ≥80 with DLBCL by area of residence.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of veterans age ≥80 newly diagnosed with Stage II-IV DLBCL between 2006-2023 using the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System (VACRS). Patient, disease, and treatment variables were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and via chart review. Variables were compared amongst Veterans residing at urban vs. rural addresses.

Results

We evaluated a total of 181 Veterans. Most veterans resided in an urban area (60.2%). At least 18.8% of veterans failed to start lymphoma-directed therapy, but only 6.6% of veterans were not explicitly offered treatment per documentation. In total, 68.5% of veterans were offered a curative treatment regimen by their provider; curative treatment was more likely to be offered to urban patients (68.8% vs 61.5%, p=0.86). Pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments prior to treatment were severely underutilized (2.8% and 0.6%). More urban veterans started treatment (75.2% vs 65.4%, p=0.38) and 40.9% started an anthracyclinecontaining regimen. Only 27.6% of veterans completed 6 total cycles of treatment. Only 37.6% of veterans achieved a complete response at end of treatment, although response was not reported in 46.4% of patients.

Conclusions

Most elderly veterans with DLBCL are being offered and started on a curative treatment regimen; however, most do not complete a full course of treatment. Although not statistically significant, more urban veterans were offered a curative regimen and received treatment. Wider adoption of pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments could improve response outcomes.

No evidence of pregnancy, but she is suicidal and depressed after ‘my baby died’

CASE Depressed after she says her baby died

Ms. R, age 50, is an African-American woman who presents to a psychiatric hospital under an involuntary commitment executed by local law enforcement. Her sister called the authorities because Ms. R reportedly told her that she is “very depressed” and wants to “end [her] life” by taking an overdose of medications after the death of her newborn 1 week earlier.

Ms. R states that she delivered a child at “full term” in the emergency department of an outside community hospital, and that her current psychiatric symptoms began after the child died from “SIDS” [sudden infant death syndrome] shortly after birth.

Ms. R describes depressive symptoms including depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased energy, feelings of guilt, decreased concentration, poor sleep, and suicidal ideation. She denies substance use or a medical condition that could have induced these symptoms, and denies symptoms of mania, anxiety, or psychosis at admission or during the previous year.

Ms. R reports a history of manic episodes that includes periods of elevated mood or irritability, impulsivity, increased energy, excessive spending despite negative consequences, lack of need for sleep, rapid thoughts, and rapid speech that impaired her social and occupational functioning. Her most recent manic episode was approximately 3 years before this admission. She reports a previous suicide attempt and a history of physical abuse from a former intimate partner.

Neither the findings of a physical examination nor the results of a screening test for serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) are consistent with pregnancy. Ms. R’s medical record reveals that she was hospitalized for a “cardiac workup” a week earlier and requested investigation of possible pregnancy, which was negative. Records also reveal that she had a hysterectomy 10 years earlier.

Although Ms. R’s sister and boyfriend support her claim of pregnancy, the patient’s young adult son refutes it and states that she “does stuff like this for attention.” Her son also reports receiving a forged sonogram picture that his mother found online 1 month earlier. Ms. R presents an obituary from a local newspaper for the child but, on further investigation, the photograph of the infant was discovered to be of another child, also obtained online. Ms. R’s family denies knowledge of potential external reward Ms. R could gain by claiming to be pregnant.

Which of the following diagnoses can be considered after Ms. R’s initial presentation?

a) somatic symptom disorder

b) major depressive disorder

c) bipolar I disorder

d) delusional disorder

The authors’ observations

Ms. R reported the recent death of a newborn that was incompatible with her medical history. Her family members revealed that Ms. R made an active effort to deceive them about the reported pregnancy. She also exhibited symptoms of a major depressive episode in the context of previous manic episodes and expressed suicidal ideation.

The first step in the diagnostic pathway was to rule out possible medical explanations, including pregnancy, which could account for the patient’s symptoms. Although the serum βHCG level usually returns to non-pregnant levels 2 to 4 weeks after delivery, it can take even longer in some women.1 The absence of βHCG along with the recorded history of hysterectomy indicated that Ms. R was not pregnant at the time of testing or within the preceding few weeks. Once medical anomalies and substance use were ruled out, further classification of the psychiatric condition was undertaken.

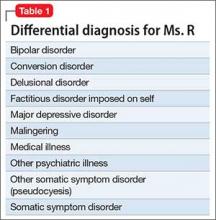

One aspect of establishing a diagnosis for Ms. R is determining the presence of psychosis (eg, delusional thinking) (Table 1). Ms. R deliberately fabricated evidence of her pregnancy and manipulated family members, which indicated a low likelihood of delusions and supported a diagnostic alternative to psychosis.

Ms. R has a well-described history of manic episodes with current symptoms of a major depressive episode. The treatment team makes a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed. The depressive symptoms Ms. R described were consistent with bipolar depression but did not explain her report of a pregnancy that is inconsistent with reality.

As is the case with Ms. R, diagnostic clarity often requires observation and evaluation over time. Building a strong therapeutic relationship with Ms. R in the context of an appropriate treatment plan allows the treatment team to explore the origin, motivations, and evolution of her thought content while managing her illness.

Confronting a patient about her false claims is likely to result in which of the following?

a) spontaneous resolution of symptoms

b) improved therapeutic alliance

c) degradation of the patient’s coping mechanism

d) violent outbursts by the patient

EVALUATION Confrontation

At admission, Ms. R remains resolute that she was pregnant and is suffering immense psychological distress secondary to the death of her child. Early in the treatment course, she is confronted with evidence indicating that her pregnancy was impossible. Shortly after this interaction, nursing staff alerts the treating physician that Ms. R experienced a “seizure-like spell” characterized by gross non-stereotyped jerking of the upper extremities, intact orientation, retention of bowel and bladder function, and coherent speech consistent with a diagnosis of pseudoseizure.2

Ms. R is transferred to a tertiary care facility for neurologic evaluation and observation. Ms. R repeatedly presents a photograph that she claims to be of her deceased child and implores the allied treatment team to advocate for discharge. Evaluation of Ms. R’s neurologic symptoms revealed no medical explanation for the “seizure-like spell” and she is transferred to the inpatient psychiatric hospital.

Upon return to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Ms. R receives intensive psychological exploration of her symptoms, thought content, and the foundation of her pregnancy claim. Within days, she acknowledges that the pregnancy was “not real” and that she was conscious of this fact in the months prior to hospitalization. She cites turmoil in her romantic relationship as the primary stimulus for her actions.

The authors’ observations

Ms. R’s reported pregnancy was not a delusion, but rather a deceitful exposition constructed with appropriate reality testing and a conscious awareness of the manipulation. This eliminated delusions as the explanation of her pregnancy claim. Although Ms. R initially rejected evidence refuting her belief of pregnancy, she recognized and accepted reality with appropriate intervention.

Factitious disorder vs malingering

Factitious disorder and malingering can present with intentional induction or report of symptoms or signs of a physical abnormality:

Factitious disorder imposed on the self is a willful misrepresentation or fabrication of signs or symptoms of an illness by a person in the absence of obvious personal gain that cannot be explained by a separate physical or mental illness (Table 2).3,4

Malingering is the intentional production or exaggeration of physical or psychological signs or symptoms with obvious secondary gain.

Malingering can be excluded in Ms. R’s case: She did not gain external reward by falsely reporting pregnancy. Although DSM-IV-TR (Table 2) assumes that the motivation for the patient with factitious disorder is to assume the sick role, DSM-5 merely states that the she (he) should present themselves as ill, impaired, or injured.3,4

Ms. R’s treatment team diagnosed factitious disorder imposed on self after careful exclusion of other causes for her symptoms. Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, also was diagnosed after considering Ms. R’s previous history of manic episodes and depressive symptoms at presentation.

Factitious disorder and other psychiatric conditions often are comorbid. Bipolar disorder, as in Ms. R’s case, as well as major depressive disorder commonly are comorbid with factitious disorder. It is also important to note that factitious disorder often occurs in the context of a personality disorder.5

Which of the following medications are FDA-approved for treating factitious disorder?

a) olanzapine-fluoxetine combination

b) lurasidone

c) valproic acid

d) all of the above

e) no medications are approved for treating factitious disorder

TREATMENT Support, drug therapy

Treatment of Ms. R’s factitious disorder consists of psychological interventions via psychotherapy and strengthening of social support. She participates in daily individual therapy sessions as well as several group therapy activities. Ms. R engages with her social worker to facilitate a successful transition to an appropriate support network and access community resources to aid her wellness.

The treatment team feels that her diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, warrants pharmacologic intervention. Ms. R agrees to begin a mood stabilizer, valproic acid, instead of medications FDA-approved to treat bipolar depression, such as lurasidone or quetiapine, because she reports good efficacy and tolerability when she took it during a major depressive episode approximately 4 years earlier.

Valproic acid is started at 250 mg/d and increased to 1,000 mg/d. Ms. R tolerates the medication without observed or reported adverse effects.

The authors’ observations

Managing factitious disorder can be challenging; patients can evoke strong feelings of countertransference during treatment.3,6,7 Providers might feel that the patient does not need to be treated, or that the patient is “not really sick.” This may induce anger and animosity toward the patient (therapeutic nihilism).8 These negative emotions are likely to disrupt the patient–provider relationship and exacerbate the patient’s symptoms.

It is generally accepted that the patient should be made aware of the treatment plan, in an indirect and tactful way, so that the patient does not feel “outed.” Unmasking the patient—the process of instilling insight—is a delicate step and can be a stressful time for the patient.9 A confrontational approach often places the patient’s sick role in doubt and does not address the pathological aspect of the disorder.

It is rare for a patient to admit to fabricating symptoms; confronted, the patient is likely to double their efforts to maintain the rouse of a fictional disease.10,11 It is important for the treatment team to be aware that patients frequently leave the treatment facility against medical advice, seek a different provider, or even pursue legal action for defamation against the treating physician.

Treating comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions is important for successful management of a patient with factitious disorder. Initiating valproic acid to address Ms. R’s bipolar depression contributed to her overall psychiatric stability. Initial treatment with a medication that is FDA-approved for treating bipolar depression, such as lurasidone, quetiapine, or olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, should be considered as an alternative. We chose valproic acid for Ms. R because of its previous efficacy, good tolerability, and the patient’s high level of comfort with the medication.

Which of the following are risk factors for factitious disorder?

a) lengthy medical treatments or hospitalizations as a child

b) female sex

c) experience as a health care worker

d) all of the above

OUTCOME Stabilization

Successful treatment during Ms. R’s inpatient psychiatric admission results in improved insight, remission of suicidal ideation, and stabilization of mood lability. She is discharged to the care of her family with a plan to follow up with a psychotherapist and psychiatrist. Continued administration of valproic acid continues to be effective after discharge.

Ms. R engages in frequent follow-up with outpatient psychiatric services. She remains engaged in psychotherapy and psychiatric care 1 year after discharge. Ms. R has made no report of pregnancy or required hospitalization during this time. She expresses trust in the mental health care system and acknowledges the role treatment played in her improvement.

1. Reyes FI, Winter JS, Faiman C. Postpartum disappearance of chorionic gonadotropin from the maternal and neonatal circulations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(5):486-489.

2. Avbersek A, Sisodiya S. Does the primary literature provide support for clinical signs used to distinguish psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epileptic seizures? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(7):719-725.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

5. Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HM, Dietrich E, et al. Artifactual disorders—between deception and self-mutilation. Experiences in consultation psychiatry at a university clinic [in German]. Nervenarzt. 1998;69(5):401-409.

6. Feldman MD, Feldman JM. Tangled in the web: countertransference in the therapy of factitious disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1995;25(4):389-399.

7. Wedel KR. A therapeutic confrontation approach to treating patients with factitious illness. Soc Work. 1971;16(2):69-73.

8. Feldman MD, Hamilton JC, Deemer HN. Factitious disorder. In: Phillips KA, ed. Somatoform and factitious disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001:129-159.

9. Scher LM, Knudsen P, Leamon M. Somatic symptom and related disorders. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Weiss Roberts L, eds. The American Publishing Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014:531-556.

10. Lipsitt DR. Introduction. In: Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ, eds. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996:xix-xxviii.

11. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Confronting patients about a factitious disorder [in Dutch]. Ned Tidjschr Geneeskd. 2000;144(12):545-548.

CASE Depressed after she says her baby died

Ms. R, age 50, is an African-American woman who presents to a psychiatric hospital under an involuntary commitment executed by local law enforcement. Her sister called the authorities because Ms. R reportedly told her that she is “very depressed” and wants to “end [her] life” by taking an overdose of medications after the death of her newborn 1 week earlier.

Ms. R states that she delivered a child at “full term” in the emergency department of an outside community hospital, and that her current psychiatric symptoms began after the child died from “SIDS” [sudden infant death syndrome] shortly after birth.

Ms. R describes depressive symptoms including depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased energy, feelings of guilt, decreased concentration, poor sleep, and suicidal ideation. She denies substance use or a medical condition that could have induced these symptoms, and denies symptoms of mania, anxiety, or psychosis at admission or during the previous year.

Ms. R reports a history of manic episodes that includes periods of elevated mood or irritability, impulsivity, increased energy, excessive spending despite negative consequences, lack of need for sleep, rapid thoughts, and rapid speech that impaired her social and occupational functioning. Her most recent manic episode was approximately 3 years before this admission. She reports a previous suicide attempt and a history of physical abuse from a former intimate partner.

Neither the findings of a physical examination nor the results of a screening test for serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) are consistent with pregnancy. Ms. R’s medical record reveals that she was hospitalized for a “cardiac workup” a week earlier and requested investigation of possible pregnancy, which was negative. Records also reveal that she had a hysterectomy 10 years earlier.

Although Ms. R’s sister and boyfriend support her claim of pregnancy, the patient’s young adult son refutes it and states that she “does stuff like this for attention.” Her son also reports receiving a forged sonogram picture that his mother found online 1 month earlier. Ms. R presents an obituary from a local newspaper for the child but, on further investigation, the photograph of the infant was discovered to be of another child, also obtained online. Ms. R’s family denies knowledge of potential external reward Ms. R could gain by claiming to be pregnant.

Which of the following diagnoses can be considered after Ms. R’s initial presentation?

a) somatic symptom disorder

b) major depressive disorder

c) bipolar I disorder

d) delusional disorder

The authors’ observations

Ms. R reported the recent death of a newborn that was incompatible with her medical history. Her family members revealed that Ms. R made an active effort to deceive them about the reported pregnancy. She also exhibited symptoms of a major depressive episode in the context of previous manic episodes and expressed suicidal ideation.

The first step in the diagnostic pathway was to rule out possible medical explanations, including pregnancy, which could account for the patient’s symptoms. Although the serum βHCG level usually returns to non-pregnant levels 2 to 4 weeks after delivery, it can take even longer in some women.1 The absence of βHCG along with the recorded history of hysterectomy indicated that Ms. R was not pregnant at the time of testing or within the preceding few weeks. Once medical anomalies and substance use were ruled out, further classification of the psychiatric condition was undertaken.

One aspect of establishing a diagnosis for Ms. R is determining the presence of psychosis (eg, delusional thinking) (Table 1). Ms. R deliberately fabricated evidence of her pregnancy and manipulated family members, which indicated a low likelihood of delusions and supported a diagnostic alternative to psychosis.

Ms. R has a well-described history of manic episodes with current symptoms of a major depressive episode. The treatment team makes a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed. The depressive symptoms Ms. R described were consistent with bipolar depression but did not explain her report of a pregnancy that is inconsistent with reality.

As is the case with Ms. R, diagnostic clarity often requires observation and evaluation over time. Building a strong therapeutic relationship with Ms. R in the context of an appropriate treatment plan allows the treatment team to explore the origin, motivations, and evolution of her thought content while managing her illness.

Confronting a patient about her false claims is likely to result in which of the following?

a) spontaneous resolution of symptoms

b) improved therapeutic alliance

c) degradation of the patient’s coping mechanism

d) violent outbursts by the patient

EVALUATION Confrontation

At admission, Ms. R remains resolute that she was pregnant and is suffering immense psychological distress secondary to the death of her child. Early in the treatment course, she is confronted with evidence indicating that her pregnancy was impossible. Shortly after this interaction, nursing staff alerts the treating physician that Ms. R experienced a “seizure-like spell” characterized by gross non-stereotyped jerking of the upper extremities, intact orientation, retention of bowel and bladder function, and coherent speech consistent with a diagnosis of pseudoseizure.2

Ms. R is transferred to a tertiary care facility for neurologic evaluation and observation. Ms. R repeatedly presents a photograph that she claims to be of her deceased child and implores the allied treatment team to advocate for discharge. Evaluation of Ms. R’s neurologic symptoms revealed no medical explanation for the “seizure-like spell” and she is transferred to the inpatient psychiatric hospital.

Upon return to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Ms. R receives intensive psychological exploration of her symptoms, thought content, and the foundation of her pregnancy claim. Within days, she acknowledges that the pregnancy was “not real” and that she was conscious of this fact in the months prior to hospitalization. She cites turmoil in her romantic relationship as the primary stimulus for her actions.

The authors’ observations

Ms. R’s reported pregnancy was not a delusion, but rather a deceitful exposition constructed with appropriate reality testing and a conscious awareness of the manipulation. This eliminated delusions as the explanation of her pregnancy claim. Although Ms. R initially rejected evidence refuting her belief of pregnancy, she recognized and accepted reality with appropriate intervention.

Factitious disorder vs malingering

Factitious disorder and malingering can present with intentional induction or report of symptoms or signs of a physical abnormality:

Factitious disorder imposed on the self is a willful misrepresentation or fabrication of signs or symptoms of an illness by a person in the absence of obvious personal gain that cannot be explained by a separate physical or mental illness (Table 2).3,4

Malingering is the intentional production or exaggeration of physical or psychological signs or symptoms with obvious secondary gain.

Malingering can be excluded in Ms. R’s case: She did not gain external reward by falsely reporting pregnancy. Although DSM-IV-TR (Table 2) assumes that the motivation for the patient with factitious disorder is to assume the sick role, DSM-5 merely states that the she (he) should present themselves as ill, impaired, or injured.3,4

Ms. R’s treatment team diagnosed factitious disorder imposed on self after careful exclusion of other causes for her symptoms. Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, also was diagnosed after considering Ms. R’s previous history of manic episodes and depressive symptoms at presentation.

Factitious disorder and other psychiatric conditions often are comorbid. Bipolar disorder, as in Ms. R’s case, as well as major depressive disorder commonly are comorbid with factitious disorder. It is also important to note that factitious disorder often occurs in the context of a personality disorder.5

Which of the following medications are FDA-approved for treating factitious disorder?

a) olanzapine-fluoxetine combination

b) lurasidone

c) valproic acid

d) all of the above

e) no medications are approved for treating factitious disorder

TREATMENT Support, drug therapy

Treatment of Ms. R’s factitious disorder consists of psychological interventions via psychotherapy and strengthening of social support. She participates in daily individual therapy sessions as well as several group therapy activities. Ms. R engages with her social worker to facilitate a successful transition to an appropriate support network and access community resources to aid her wellness.

The treatment team feels that her diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, warrants pharmacologic intervention. Ms. R agrees to begin a mood stabilizer, valproic acid, instead of medications FDA-approved to treat bipolar depression, such as lurasidone or quetiapine, because she reports good efficacy and tolerability when she took it during a major depressive episode approximately 4 years earlier.

Valproic acid is started at 250 mg/d and increased to 1,000 mg/d. Ms. R tolerates the medication without observed or reported adverse effects.

The authors’ observations

Managing factitious disorder can be challenging; patients can evoke strong feelings of countertransference during treatment.3,6,7 Providers might feel that the patient does not need to be treated, or that the patient is “not really sick.” This may induce anger and animosity toward the patient (therapeutic nihilism).8 These negative emotions are likely to disrupt the patient–provider relationship and exacerbate the patient’s symptoms.

It is generally accepted that the patient should be made aware of the treatment plan, in an indirect and tactful way, so that the patient does not feel “outed.” Unmasking the patient—the process of instilling insight—is a delicate step and can be a stressful time for the patient.9 A confrontational approach often places the patient’s sick role in doubt and does not address the pathological aspect of the disorder.

It is rare for a patient to admit to fabricating symptoms; confronted, the patient is likely to double their efforts to maintain the rouse of a fictional disease.10,11 It is important for the treatment team to be aware that patients frequently leave the treatment facility against medical advice, seek a different provider, or even pursue legal action for defamation against the treating physician.

Treating comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions is important for successful management of a patient with factitious disorder. Initiating valproic acid to address Ms. R’s bipolar depression contributed to her overall psychiatric stability. Initial treatment with a medication that is FDA-approved for treating bipolar depression, such as lurasidone, quetiapine, or olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, should be considered as an alternative. We chose valproic acid for Ms. R because of its previous efficacy, good tolerability, and the patient’s high level of comfort with the medication.

Which of the following are risk factors for factitious disorder?

a) lengthy medical treatments or hospitalizations as a child

b) female sex

c) experience as a health care worker

d) all of the above

OUTCOME Stabilization

Successful treatment during Ms. R’s inpatient psychiatric admission results in improved insight, remission of suicidal ideation, and stabilization of mood lability. She is discharged to the care of her family with a plan to follow up with a psychotherapist and psychiatrist. Continued administration of valproic acid continues to be effective after discharge.

Ms. R engages in frequent follow-up with outpatient psychiatric services. She remains engaged in psychotherapy and psychiatric care 1 year after discharge. Ms. R has made no report of pregnancy or required hospitalization during this time. She expresses trust in the mental health care system and acknowledges the role treatment played in her improvement.

CASE Depressed after she says her baby died

Ms. R, age 50, is an African-American woman who presents to a psychiatric hospital under an involuntary commitment executed by local law enforcement. Her sister called the authorities because Ms. R reportedly told her that she is “very depressed” and wants to “end [her] life” by taking an overdose of medications after the death of her newborn 1 week earlier.

Ms. R states that she delivered a child at “full term” in the emergency department of an outside community hospital, and that her current psychiatric symptoms began after the child died from “SIDS” [sudden infant death syndrome] shortly after birth.

Ms. R describes depressive symptoms including depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased energy, feelings of guilt, decreased concentration, poor sleep, and suicidal ideation. She denies substance use or a medical condition that could have induced these symptoms, and denies symptoms of mania, anxiety, or psychosis at admission or during the previous year.

Ms. R reports a history of manic episodes that includes periods of elevated mood or irritability, impulsivity, increased energy, excessive spending despite negative consequences, lack of need for sleep, rapid thoughts, and rapid speech that impaired her social and occupational functioning. Her most recent manic episode was approximately 3 years before this admission. She reports a previous suicide attempt and a history of physical abuse from a former intimate partner.

Neither the findings of a physical examination nor the results of a screening test for serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) are consistent with pregnancy. Ms. R’s medical record reveals that she was hospitalized for a “cardiac workup” a week earlier and requested investigation of possible pregnancy, which was negative. Records also reveal that she had a hysterectomy 10 years earlier.

Although Ms. R’s sister and boyfriend support her claim of pregnancy, the patient’s young adult son refutes it and states that she “does stuff like this for attention.” Her son also reports receiving a forged sonogram picture that his mother found online 1 month earlier. Ms. R presents an obituary from a local newspaper for the child but, on further investigation, the photograph of the infant was discovered to be of another child, also obtained online. Ms. R’s family denies knowledge of potential external reward Ms. R could gain by claiming to be pregnant.

Which of the following diagnoses can be considered after Ms. R’s initial presentation?

a) somatic symptom disorder

b) major depressive disorder

c) bipolar I disorder

d) delusional disorder

The authors’ observations

Ms. R reported the recent death of a newborn that was incompatible with her medical history. Her family members revealed that Ms. R made an active effort to deceive them about the reported pregnancy. She also exhibited symptoms of a major depressive episode in the context of previous manic episodes and expressed suicidal ideation.

The first step in the diagnostic pathway was to rule out possible medical explanations, including pregnancy, which could account for the patient’s symptoms. Although the serum βHCG level usually returns to non-pregnant levels 2 to 4 weeks after delivery, it can take even longer in some women.1 The absence of βHCG along with the recorded history of hysterectomy indicated that Ms. R was not pregnant at the time of testing or within the preceding few weeks. Once medical anomalies and substance use were ruled out, further classification of the psychiatric condition was undertaken.

One aspect of establishing a diagnosis for Ms. R is determining the presence of psychosis (eg, delusional thinking) (Table 1). Ms. R deliberately fabricated evidence of her pregnancy and manipulated family members, which indicated a low likelihood of delusions and supported a diagnostic alternative to psychosis.

Ms. R has a well-described history of manic episodes with current symptoms of a major depressive episode. The treatment team makes a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed. The depressive symptoms Ms. R described were consistent with bipolar depression but did not explain her report of a pregnancy that is inconsistent with reality.

As is the case with Ms. R, diagnostic clarity often requires observation and evaluation over time. Building a strong therapeutic relationship with Ms. R in the context of an appropriate treatment plan allows the treatment team to explore the origin, motivations, and evolution of her thought content while managing her illness.

Confronting a patient about her false claims is likely to result in which of the following?

a) spontaneous resolution of symptoms

b) improved therapeutic alliance

c) degradation of the patient’s coping mechanism

d) violent outbursts by the patient

EVALUATION Confrontation

At admission, Ms. R remains resolute that she was pregnant and is suffering immense psychological distress secondary to the death of her child. Early in the treatment course, she is confronted with evidence indicating that her pregnancy was impossible. Shortly after this interaction, nursing staff alerts the treating physician that Ms. R experienced a “seizure-like spell” characterized by gross non-stereotyped jerking of the upper extremities, intact orientation, retention of bowel and bladder function, and coherent speech consistent with a diagnosis of pseudoseizure.2

Ms. R is transferred to a tertiary care facility for neurologic evaluation and observation. Ms. R repeatedly presents a photograph that she claims to be of her deceased child and implores the allied treatment team to advocate for discharge. Evaluation of Ms. R’s neurologic symptoms revealed no medical explanation for the “seizure-like spell” and she is transferred to the inpatient psychiatric hospital.

Upon return to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Ms. R receives intensive psychological exploration of her symptoms, thought content, and the foundation of her pregnancy claim. Within days, she acknowledges that the pregnancy was “not real” and that she was conscious of this fact in the months prior to hospitalization. She cites turmoil in her romantic relationship as the primary stimulus for her actions.

The authors’ observations

Ms. R’s reported pregnancy was not a delusion, but rather a deceitful exposition constructed with appropriate reality testing and a conscious awareness of the manipulation. This eliminated delusions as the explanation of her pregnancy claim. Although Ms. R initially rejected evidence refuting her belief of pregnancy, she recognized and accepted reality with appropriate intervention.

Factitious disorder vs malingering

Factitious disorder and malingering can present with intentional induction or report of symptoms or signs of a physical abnormality:

Factitious disorder imposed on the self is a willful misrepresentation or fabrication of signs or symptoms of an illness by a person in the absence of obvious personal gain that cannot be explained by a separate physical or mental illness (Table 2).3,4

Malingering is the intentional production or exaggeration of physical or psychological signs or symptoms with obvious secondary gain.

Malingering can be excluded in Ms. R’s case: She did not gain external reward by falsely reporting pregnancy. Although DSM-IV-TR (Table 2) assumes that the motivation for the patient with factitious disorder is to assume the sick role, DSM-5 merely states that the she (he) should present themselves as ill, impaired, or injured.3,4

Ms. R’s treatment team diagnosed factitious disorder imposed on self after careful exclusion of other causes for her symptoms. Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, also was diagnosed after considering Ms. R’s previous history of manic episodes and depressive symptoms at presentation.

Factitious disorder and other psychiatric conditions often are comorbid. Bipolar disorder, as in Ms. R’s case, as well as major depressive disorder commonly are comorbid with factitious disorder. It is also important to note that factitious disorder often occurs in the context of a personality disorder.5

Which of the following medications are FDA-approved for treating factitious disorder?

a) olanzapine-fluoxetine combination

b) lurasidone

c) valproic acid

d) all of the above

e) no medications are approved for treating factitious disorder

TREATMENT Support, drug therapy

Treatment of Ms. R’s factitious disorder consists of psychological interventions via psychotherapy and strengthening of social support. She participates in daily individual therapy sessions as well as several group therapy activities. Ms. R engages with her social worker to facilitate a successful transition to an appropriate support network and access community resources to aid her wellness.

The treatment team feels that her diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed, warrants pharmacologic intervention. Ms. R agrees to begin a mood stabilizer, valproic acid, instead of medications FDA-approved to treat bipolar depression, such as lurasidone or quetiapine, because she reports good efficacy and tolerability when she took it during a major depressive episode approximately 4 years earlier.

Valproic acid is started at 250 mg/d and increased to 1,000 mg/d. Ms. R tolerates the medication without observed or reported adverse effects.

The authors’ observations

Managing factitious disorder can be challenging; patients can evoke strong feelings of countertransference during treatment.3,6,7 Providers might feel that the patient does not need to be treated, or that the patient is “not really sick.” This may induce anger and animosity toward the patient (therapeutic nihilism).8 These negative emotions are likely to disrupt the patient–provider relationship and exacerbate the patient’s symptoms.

It is generally accepted that the patient should be made aware of the treatment plan, in an indirect and tactful way, so that the patient does not feel “outed.” Unmasking the patient—the process of instilling insight—is a delicate step and can be a stressful time for the patient.9 A confrontational approach often places the patient’s sick role in doubt and does not address the pathological aspect of the disorder.

It is rare for a patient to admit to fabricating symptoms; confronted, the patient is likely to double their efforts to maintain the rouse of a fictional disease.10,11 It is important for the treatment team to be aware that patients frequently leave the treatment facility against medical advice, seek a different provider, or even pursue legal action for defamation against the treating physician.

Treating comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions is important for successful management of a patient with factitious disorder. Initiating valproic acid to address Ms. R’s bipolar depression contributed to her overall psychiatric stability. Initial treatment with a medication that is FDA-approved for treating bipolar depression, such as lurasidone, quetiapine, or olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, should be considered as an alternative. We chose valproic acid for Ms. R because of its previous efficacy, good tolerability, and the patient’s high level of comfort with the medication.

Which of the following are risk factors for factitious disorder?

a) lengthy medical treatments or hospitalizations as a child

b) female sex

c) experience as a health care worker

d) all of the above

OUTCOME Stabilization

Successful treatment during Ms. R’s inpatient psychiatric admission results in improved insight, remission of suicidal ideation, and stabilization of mood lability. She is discharged to the care of her family with a plan to follow up with a psychotherapist and psychiatrist. Continued administration of valproic acid continues to be effective after discharge.

Ms. R engages in frequent follow-up with outpatient psychiatric services. She remains engaged in psychotherapy and psychiatric care 1 year after discharge. Ms. R has made no report of pregnancy or required hospitalization during this time. She expresses trust in the mental health care system and acknowledges the role treatment played in her improvement.

1. Reyes FI, Winter JS, Faiman C. Postpartum disappearance of chorionic gonadotropin from the maternal and neonatal circulations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(5):486-489.

2. Avbersek A, Sisodiya S. Does the primary literature provide support for clinical signs used to distinguish psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epileptic seizures? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(7):719-725.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

5. Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HM, Dietrich E, et al. Artifactual disorders—between deception and self-mutilation. Experiences in consultation psychiatry at a university clinic [in German]. Nervenarzt. 1998;69(5):401-409.

6. Feldman MD, Feldman JM. Tangled in the web: countertransference in the therapy of factitious disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1995;25(4):389-399.

7. Wedel KR. A therapeutic confrontation approach to treating patients with factitious illness. Soc Work. 1971;16(2):69-73.

8. Feldman MD, Hamilton JC, Deemer HN. Factitious disorder. In: Phillips KA, ed. Somatoform and factitious disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001:129-159.

9. Scher LM, Knudsen P, Leamon M. Somatic symptom and related disorders. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Weiss Roberts L, eds. The American Publishing Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014:531-556.

10. Lipsitt DR. Introduction. In: Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ, eds. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996:xix-xxviii.

11. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Confronting patients about a factitious disorder [in Dutch]. Ned Tidjschr Geneeskd. 2000;144(12):545-548.

1. Reyes FI, Winter JS, Faiman C. Postpartum disappearance of chorionic gonadotropin from the maternal and neonatal circulations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(5):486-489.

2. Avbersek A, Sisodiya S. Does the primary literature provide support for clinical signs used to distinguish psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epileptic seizures? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(7):719-725.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

5. Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HM, Dietrich E, et al. Artifactual disorders—between deception and self-mutilation. Experiences in consultation psychiatry at a university clinic [in German]. Nervenarzt. 1998;69(5):401-409.

6. Feldman MD, Feldman JM. Tangled in the web: countertransference in the therapy of factitious disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1995;25(4):389-399.

7. Wedel KR. A therapeutic confrontation approach to treating patients with factitious illness. Soc Work. 1971;16(2):69-73.

8. Feldman MD, Hamilton JC, Deemer HN. Factitious disorder. In: Phillips KA, ed. Somatoform and factitious disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001:129-159.

9. Scher LM, Knudsen P, Leamon M. Somatic symptom and related disorders. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Weiss Roberts L, eds. The American Publishing Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014:531-556.

10. Lipsitt DR. Introduction. In: Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ, eds. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996:xix-xxviii.

11. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Confronting patients about a factitious disorder [in Dutch]. Ned Tidjschr Geneeskd. 2000;144(12):545-548.