User login

A Paradigm Shift in Evaluating and Investigating the Etiology of Bloating

Introduction

Abdominal bloating is a common condition affecting up to 3.5% of people globally (4.6% in women and 2.4% in men),1 with 13.9% of the US population reporting bloating in the past 7 days.2 The prevalence of bloating and distention exceeds 50% when linked to disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs) such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), constipation, gastroparesis, and functional dyspepsia (FD).3,4 According to the Rome IV criteria, functional bloating and distention (FABD) patients are characterized by recurrent symptoms of abdominal fullness or pressure (bloating), or a visible increase in abdominal girth (distention) occurring at least 1 day per week for 3 consecutive months with an onset of 6 months and without predominant pain or altered bowel habits.5

Prolonged abdominal bloating and distention (ABD) can significantly impact quality of life and work productivity and can lead to increased medical consultations.2 Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms are involved in ABD that complicate the clinical management.4 There is an unmet need to understand the underlying mechanisms that lead to the development of ABD such as, food intolerance, abnormal viscerosomatic reflex, visceral hypersensitivity, and gut microbial dysbiosis. Recent advancements and acceptance of a multidisciplinary management of ABD have shifted the paradigm from merely treating symptoms to subtyping the condition and identifying overlaps with other DGBIs in order to individualize treatment that addresses the underlying pathophysiological mechanism. The recent American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) clinical update provided insights into the best practice advice for evaluating and managing ABD based on a review of current literature and on expert opinion of coauthors.6 This article aims to deliberate a practical approach to diagnostic strategies and treatment options based on etiology to refine clinical care of patients with ABD.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

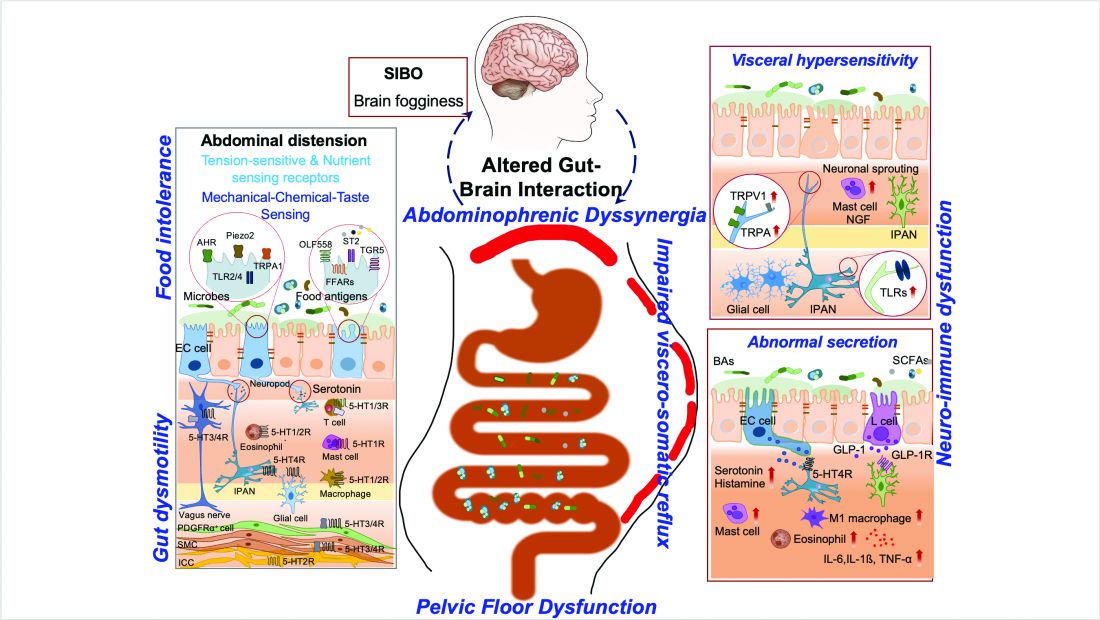

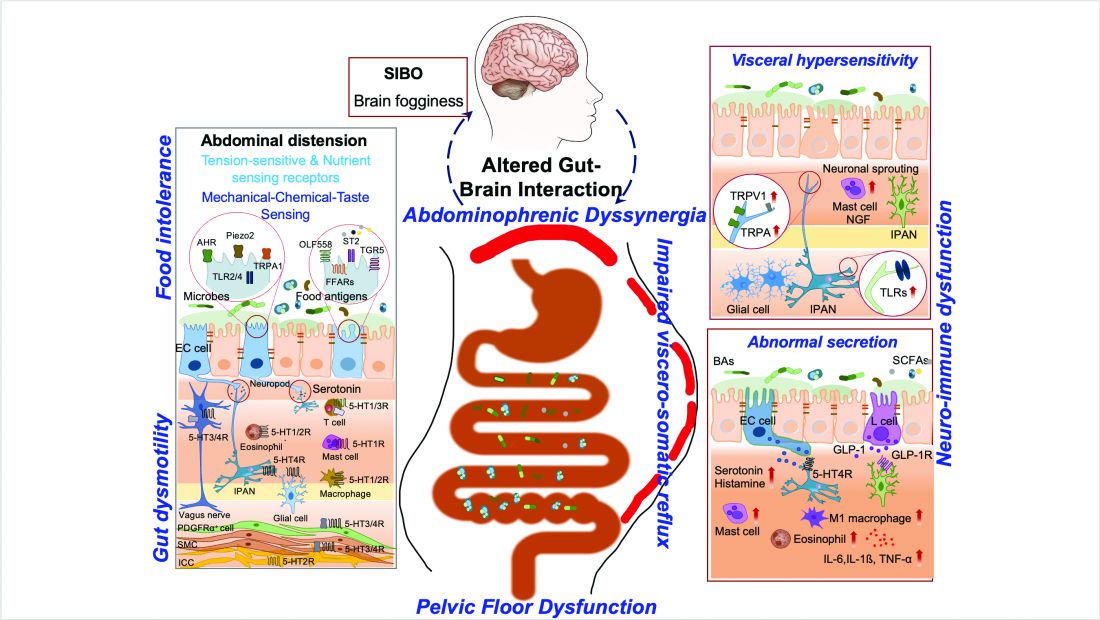

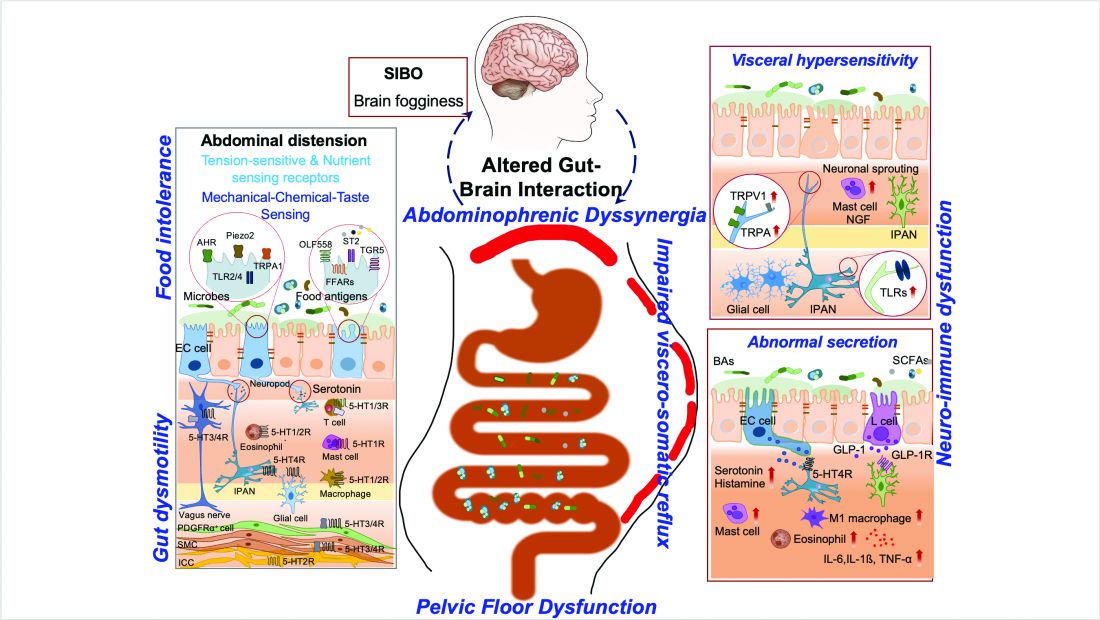

ABD can result from various pathophysiological mechanisms. This section highlights the major causes (illustrated in Figure 1).

Food intolerances

Understanding food intolerances is crucial for diagnosing and managing patients with ABD. Disaccharidase deficiency is common (e.g., lactase deficiency is found in 35%-40% of adults).7 It can be undiagnosed in patients presenting with IBS symptoms, given the overlap in presentation with a prevalence of 9% of pan-disaccharidase deficiency. Sucrase-deficient patients must often adjust sugar and carbohydrate/starch intake to relieve symptoms.7 Deficiencies in lactase and sucrase activity, along with the consumption of some artificial sweeteners (e.g., sugar alcohols and sorbitol) and fructans can lead to bloating and distention. These substances increase osmotic load, fluid retention, microbial fermentation, and visceral hypersensitivity, leading to gas production and abdominal distention. One prospective study of symptomatic patients with various DGBIs (n = 1372) reported a prevalence of lactose intolerance and malabsorption at 51% and 32%, respectively.8 Furthermore, fructose intolerance and malabsorption prevalence were 60% and 45%, respectively.8 Notably, lactase deficiency does not always cause ABD, as not all individuals with lactase deficiency experience these symptoms after consuming lactose. Patients with celiac disease (CD), non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), and gluten intolerance can also experience bloating and distention, with or without changes in bowel habits.9 In some patients with self-reported NCGS, symptoms may be due to fructans in gluten-rich foods rather than gluten itself, thus recommending the elimination of fructans may help improve symptoms.9

Visceral hypersensitivity

Visceral hypersensitivity is explained by an increased perception of gut mechano-chemical stimulation, which typically manifests in an aggravated feeling of pain, nausea, distension, and ABD.10 In the gut, food particles and gut bacteria and their derived molecules interact with neuroimmune and enteroendocrine cells causing visceral sensitivity by the proximity of gut’s neurons to immune cells activated by them and leading to inflammatory reactions (Figure 1).

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Patients with anorectal motor dysfunction often experience difficulty in effectively evacuating both gas and stool, leading to ABD.12 Impaired ability to expel gas and stool results in prolonged balloon expulsion times, which correlates with symptoms of distention in patients with constipation.

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia is characterized as a paradoxical viscerosomatic reflex response to minimal gaseous distention in individuals with FABD.13 In this condition, the diaphragm contracts (descends), and the anterior abdominal wall muscles relax in response to the presence of gas. This response is opposite to the normal physiological response to increased intraluminal gas, where the diaphragm relaxes and the anterior abdominal muscles contract to increase the craniocaudal capacity of the abdominal cavity without causing abdominal protrusion.13 Patients with FABD exhibit significant abdominal wall protrusion and diaphragmatic descent even with relatively small increases in intraluminal gas.11 Understanding the role of abdominophrenic dyssynergia in abdominal bloating and distention is essential for effective diagnosis and management of the patients.

Gut dysmotility

Gut dysmotility is a crucial factor that can contribute to FABD. Gut dysmotility affects the movement of contents through the GI tract, accumulating gas and stool, directly contributing to bloating and distention. A prospective study involving over 2000 patients with functional constipation and constipation predominant-IBS (IBS-C) found that more than 90% of these patients reported symptoms of bloating.14 Furthermore, in IBS-C patients, those with prolonged colonic transit exhibited greater abdominal distention compared to those with normal gut transit times. In patients with gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying resulting in prolonged retention of stomach contents is the main factor in the generation of bloating symptoms.4

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO is overrepresented in various conditions, including IBS, FD, diabetes, gastrointestinal (GI) surgery patients and obesity, and can play an important role in generating ABD. Excess bacteria in the small intestine ferment carbohydrates, producing gas that stretches and distends the small intestine, leading to these symptoms. Additionally, altered sensation and abnormal viscerosomatic reflexes may contribute to SIBO-related bloating.4 One recent study noted decreased duodenal phylogenetic diversity in individuals who developed postprandial bloating.15 Increased methane levels caused by intestinal methanogen overgrowth, primarily the archaea Methanobrevibacter smithii, is possibly responsible for ABD in patients with IBS-C.16 Testing for SIBO in patients with ABD is generally only recommended if there are clear risk factors or severe symptoms warranting a test-and-treat approach.

Practical Diagnosis

Diagnosing ABD typically does not require extensive laboratory testing, imaging, or endoscopy unless there are alarm features or significant changes in symptoms. Here is the AGA clinical update on best practice advice6 for when to conduct further testing:

Diagnostic tests should be considered if patients exhibit:

- Recent onset or worsening of dyspepsia or abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- GI bleeding

- Unintentional weight loss exceeding 10% of body weight

- Chronic diarrhea

- Family history of GI malignancy, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease

Physical examination

If visible abdominal distention is present, a thorough abdominal examination can help identify potential issues:

- Tympany to percussion suggests bowel dilation.

- Abnormal bowel sounds may indicate obstruction or ileus.

- A succussion splash could indicate the presence of ascites and obstruction.

- Any abnormalities discovered during the physical exam should prompt further investigation with imaging, such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or ultrasound, to evaluate for ascites, masses, or increased bowel gas due to ileus, obstruction, or pseudo-obstruction.

Radiologic imaging, laboratory testing and endoscopy

- An abdominal x-ray may reveal an increased stool burden, suggesting the need for further evaluation of slow transit constipation or a pelvic floor disorder, particularly in patients with functional constipation, IBS-mixed, or IBS-C.

- Hyperglycemia, weight gain, and bloating can be a presenting sign of ovarian cancer therefore all women should continue pelvic exams as dictated by the gynecologic societies. The need for an annual pelvic exam should be discussed with health care professionals especially in those with family history of ovarian cancer.

- An upper endoscopy may be warranted for patients over 40 years old with dyspeptic symptoms and abdominal bloating or distention, especially in regions with a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori.

- Chronic pancreatitis, indicated by bloating and pain, may necessitate fecal elastase testing to assess pancreatic function.

The expert review in the AGA clinical update provides step-by-step advice regarding the best practices6 for diagnosis and identifying who to test for ABD.

Treatment Options

The following sections highlight recent best practice advice on therapeutic approaches for treating ABD.

Dietary interventions

Specific foods may trigger bloating and abdominal distention, especially in patients with overlapping DGBIs. However, only a few studies have evaluated dietary restriction specifically for patients with primary ABD. Restricting non-absorbable sugars led to symptomatic improvement in 81% of patients with FABD who had documented sugar malabsorption.17 Two studies have shown that IBS patients treated with a low-fermentable, oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides (FODMAP) diet noted improvement in ABD and that restricting fructans initially may be the most optimal.18 A recent study showed that the Mediterranean diet improved IBS symptoms, including abdominal pain and bloating.19 It should be noted restrictive diets are efficacious but come with short- and long-term challenges. If empiric treatment and/or therapeutic testing do not resolve symptoms, a referral to a dietitian can be useful. Dietitians can provide tailored dietary advice, ensuring patients avoid trigger foods while maintaining a balanced and nutritious diet.

Prokinetics and laxatives

Prokinetic agents are used to treat symptoms of FD, gastroparesis, chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), and IBS. A meta-analysis of 13 trials found all constipation medications superior to placebo for treating abdominal bloating in patients with IBS-C.20

Probiotics

Treatment with probiotics is recommended for bloating or distention. One double-blind placebo-controlled trial with two separate probiotics, Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus acidophilus, showed improvements in global GI symptoms of patients with DGBI at 8 weeks versus placebo, with improvements in bloating symptoms.21

Antibiotics

The most commonly studied antibiotic for treating bloating is rifaximin.22 Global symptomatic improvement in IBS patients treated with antibiotics has correlated with the normalization of hydrogen levels in lactulose hydrogen breath tests.22 Patients with non-constipation IBS randomized to rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 14 days had a greater proportion of relief of IBS-related bloating compared to placebo for at least 2 of the first 4 weeks after treatment.22 Future research warrants use of narrow-spectrum antibiotics study for FABD as the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may deplete commensals forever, resulting in metabolic disorders.

Biofeedback therapy

Anorectal biofeedback therapy may help with ABD, particularly in patients with IBS-C and chronic constipation. One study noted that post-biofeedback therapy, myoelectric activity of the intercostals and diaphragm decreased, and internal oblique myoelectric activity increased.23 This study also showed ascent of the diaphragm and decreased girth, improving distention.

Central neuromodulators

As bloating results from multiple disturbed mechanisms, including altered gut-brain interaction, these symptoms can be amplified by psychological states such as anxiety, depression, or somatization. Central neuromodulators reduce the perception of visceral signals, re-regulate brain-gut control mechanisms, and improve psychological comorbidities.6 A large study of FD patients demonstrated that both amitriptyline (50 mg daily) and escitalopram (10 mg daily) significantly improved postprandial bloating compared to placebo.24 Antidepressants that activate noradrenergic and serotonergic pathways, including tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine and venlafaxine), show the greatest benefit in reducing visceral sensations.6

Brain-gut behavioral therapies

A recent multidisciplinary consensus report supports a myriad of potential brain-gut behavioral therapies (BGBTs) for treating DGBI.25 These therapies, including hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other modalities, may be combined with central neuromodulators and other GI treatments in a safe, noninvasive, and complementary fashion. BGBTs do not need to be symptom-specific, as they improve overall quality of life, anxiety, stress, and the burden associated with DGBIs. To date, none of the BGBTs have focused exclusively on FABD; however, prescription-based psychological therapies are now FDA-approved for use on smart apps, improving global symptoms that include bloating in IBS and FD.

Recent AGA clinical update best practices should be considered for the clinical care of patients with ABD.6

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

ABD are highly prevalent and significantly impact patients with various GI and metabolic disorders. Although our understanding of these symptoms is still evolving, evidence increasingly points to the dysregulation of the gut-brain axis and supports the application of the biopsychosocial model in treatment. This model addresses diet, motility, visceral sensitivity, pelvic floor disorders and psychosocial factors, providing a comprehensive approach to patient care.

Physician-scientists around the globe face numerous challenges when evaluating patients with these symptoms. However, the recent AGA clinical update on the best practice guidelines offers step-by-step diagnostic tests and treatment options to assist physicians in making informed decisions. . More comprehensive, large-scale, and longitudinal studies using metabolomics, capsule technologies for discovery of dysbiosis, mass spectrometry, and imaging data are needed to identify the exact contributors to disease pathogenesis, particularly those that can be targeted with pharmacologic agents. Collaborative work between gastroenterologists, dietitians, gut-brain behavioral therapists, endocrinologists, is crucial for clinical care of patients with ABD.

Careful attention to the patient’s primary symptoms and physical examination, combined with advancements in targeted diagnostics like the analysis of microbial markers, metabolites, and molecular signals, can significantly enhance patient clinical outcomes. Additionally, education and effective communication using a patient-centered care model are essential for guiding practical evaluation and individualized treatment.

Dr. Singh is assistant professor (research) at the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine. Dr. Moshiree is director of motility at Atrium Health, and clinical professor of medicine, Wake Forest Medical University, Charlotte, North Carolina.

References

1. Ballou S et al. Prevalence and associated factors of bloating: Results from the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 June. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049.

2. Oh JE et al. Abdominal bloating in the United States: Results of a survey of 88,795 Americans examining prevalence and healthcare seeking. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.031.

3. Drossman DA et al. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of gut-brain interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279.

4. Lacy BE et al. Management of chronic abdominal distension and bloating. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.056.

5. Mearin F et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031.

6. Moshiree B et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on evaluation and management of belching, abdominal bloating, and distention: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.039.

7. Viswanathan L and Rao SS. Intestinal disaccharidase deficiency in adults: evaluation and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2023 May. doi: 10.1007/s11894-023-00870-z.

8. Wilder-Smith CH et al. Fructose and lactose intolerance and malabsorption testing: the relationship with symptoms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jun. doi: 10.1111/apt.12306.

9. Skodje GI et al. Fructan, rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.040.

10. Singh R et al. Current treatment options and therapeutic insights for gastrointestinal dysmotility and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jan. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.808195.

11. Accarino A et al. Abdominal distention results from caudo-ventral redistribution of contents. Gastroenterology 2009 May. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.067.

12. Shim L et al. Prolonged balloon expulsion is predictive of abdominal distension in bloating. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Apr. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.54.

13. Villoria A et al. Abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia in patients with abdominal bloating and distension. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 May. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.408.

14. Neri L and Iovino P. Laxative Inadequate Relief Survey Group. Bloating is associated with worse quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and treatment responsiveness among patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12758.

15. Saffouri GB et al. Small intestinal microbial dysbiosis underlies symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Commun. 2019 May. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09964-7.

16. Villanueva-Millan MJ et al. Methanogens and hydrogen sulfide producing bacteria guide distinct gut microbe profiles and irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001997.

17. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Sugar malabsorption in functional abdominal bloating: a pilot study on the long-term effect of dietary treatment. Clin Nutr. 2006 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.010.

18. Böhn L et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.054.

19. Staudacher HM et al. Clinical trial: A Mediterranean diet is feasible and improves gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1111/apt.17791.

20. Nelson AD et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis: efficacy of licensed drugs for abdominal bloating in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1111/apt.16437.

21. Ringel-Kulka T et al. Probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders: a double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820ca4d6.

22. Pimentel M et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409.

23. Iovino P et al. Pelvic floor biofeedback is an effective treatment for severe bloating in disorders of gut-brain interaction with outlet dysfunction. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14264.

24. Talley NJ et al. Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: A multicenter, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.020.

25. Keefer L et al. A Rome Working Team Report on brain-gut behavior therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.015.

Introduction

Abdominal bloating is a common condition affecting up to 3.5% of people globally (4.6% in women and 2.4% in men),1 with 13.9% of the US population reporting bloating in the past 7 days.2 The prevalence of bloating and distention exceeds 50% when linked to disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs) such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), constipation, gastroparesis, and functional dyspepsia (FD).3,4 According to the Rome IV criteria, functional bloating and distention (FABD) patients are characterized by recurrent symptoms of abdominal fullness or pressure (bloating), or a visible increase in abdominal girth (distention) occurring at least 1 day per week for 3 consecutive months with an onset of 6 months and without predominant pain or altered bowel habits.5

Prolonged abdominal bloating and distention (ABD) can significantly impact quality of life and work productivity and can lead to increased medical consultations.2 Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms are involved in ABD that complicate the clinical management.4 There is an unmet need to understand the underlying mechanisms that lead to the development of ABD such as, food intolerance, abnormal viscerosomatic reflex, visceral hypersensitivity, and gut microbial dysbiosis. Recent advancements and acceptance of a multidisciplinary management of ABD have shifted the paradigm from merely treating symptoms to subtyping the condition and identifying overlaps with other DGBIs in order to individualize treatment that addresses the underlying pathophysiological mechanism. The recent American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) clinical update provided insights into the best practice advice for evaluating and managing ABD based on a review of current literature and on expert opinion of coauthors.6 This article aims to deliberate a practical approach to diagnostic strategies and treatment options based on etiology to refine clinical care of patients with ABD.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

ABD can result from various pathophysiological mechanisms. This section highlights the major causes (illustrated in Figure 1).

Food intolerances

Understanding food intolerances is crucial for diagnosing and managing patients with ABD. Disaccharidase deficiency is common (e.g., lactase deficiency is found in 35%-40% of adults).7 It can be undiagnosed in patients presenting with IBS symptoms, given the overlap in presentation with a prevalence of 9% of pan-disaccharidase deficiency. Sucrase-deficient patients must often adjust sugar and carbohydrate/starch intake to relieve symptoms.7 Deficiencies in lactase and sucrase activity, along with the consumption of some artificial sweeteners (e.g., sugar alcohols and sorbitol) and fructans can lead to bloating and distention. These substances increase osmotic load, fluid retention, microbial fermentation, and visceral hypersensitivity, leading to gas production and abdominal distention. One prospective study of symptomatic patients with various DGBIs (n = 1372) reported a prevalence of lactose intolerance and malabsorption at 51% and 32%, respectively.8 Furthermore, fructose intolerance and malabsorption prevalence were 60% and 45%, respectively.8 Notably, lactase deficiency does not always cause ABD, as not all individuals with lactase deficiency experience these symptoms after consuming lactose. Patients with celiac disease (CD), non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), and gluten intolerance can also experience bloating and distention, with or without changes in bowel habits.9 In some patients with self-reported NCGS, symptoms may be due to fructans in gluten-rich foods rather than gluten itself, thus recommending the elimination of fructans may help improve symptoms.9

Visceral hypersensitivity

Visceral hypersensitivity is explained by an increased perception of gut mechano-chemical stimulation, which typically manifests in an aggravated feeling of pain, nausea, distension, and ABD.10 In the gut, food particles and gut bacteria and their derived molecules interact with neuroimmune and enteroendocrine cells causing visceral sensitivity by the proximity of gut’s neurons to immune cells activated by them and leading to inflammatory reactions (Figure 1).

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Patients with anorectal motor dysfunction often experience difficulty in effectively evacuating both gas and stool, leading to ABD.12 Impaired ability to expel gas and stool results in prolonged balloon expulsion times, which correlates with symptoms of distention in patients with constipation.

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia is characterized as a paradoxical viscerosomatic reflex response to minimal gaseous distention in individuals with FABD.13 In this condition, the diaphragm contracts (descends), and the anterior abdominal wall muscles relax in response to the presence of gas. This response is opposite to the normal physiological response to increased intraluminal gas, where the diaphragm relaxes and the anterior abdominal muscles contract to increase the craniocaudal capacity of the abdominal cavity without causing abdominal protrusion.13 Patients with FABD exhibit significant abdominal wall protrusion and diaphragmatic descent even with relatively small increases in intraluminal gas.11 Understanding the role of abdominophrenic dyssynergia in abdominal bloating and distention is essential for effective diagnosis and management of the patients.

Gut dysmotility

Gut dysmotility is a crucial factor that can contribute to FABD. Gut dysmotility affects the movement of contents through the GI tract, accumulating gas and stool, directly contributing to bloating and distention. A prospective study involving over 2000 patients with functional constipation and constipation predominant-IBS (IBS-C) found that more than 90% of these patients reported symptoms of bloating.14 Furthermore, in IBS-C patients, those with prolonged colonic transit exhibited greater abdominal distention compared to those with normal gut transit times. In patients with gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying resulting in prolonged retention of stomach contents is the main factor in the generation of bloating symptoms.4

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO is overrepresented in various conditions, including IBS, FD, diabetes, gastrointestinal (GI) surgery patients and obesity, and can play an important role in generating ABD. Excess bacteria in the small intestine ferment carbohydrates, producing gas that stretches and distends the small intestine, leading to these symptoms. Additionally, altered sensation and abnormal viscerosomatic reflexes may contribute to SIBO-related bloating.4 One recent study noted decreased duodenal phylogenetic diversity in individuals who developed postprandial bloating.15 Increased methane levels caused by intestinal methanogen overgrowth, primarily the archaea Methanobrevibacter smithii, is possibly responsible for ABD in patients with IBS-C.16 Testing for SIBO in patients with ABD is generally only recommended if there are clear risk factors or severe symptoms warranting a test-and-treat approach.

Practical Diagnosis

Diagnosing ABD typically does not require extensive laboratory testing, imaging, or endoscopy unless there are alarm features or significant changes in symptoms. Here is the AGA clinical update on best practice advice6 for when to conduct further testing:

Diagnostic tests should be considered if patients exhibit:

- Recent onset or worsening of dyspepsia or abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- GI bleeding

- Unintentional weight loss exceeding 10% of body weight

- Chronic diarrhea

- Family history of GI malignancy, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease

Physical examination

If visible abdominal distention is present, a thorough abdominal examination can help identify potential issues:

- Tympany to percussion suggests bowel dilation.

- Abnormal bowel sounds may indicate obstruction or ileus.

- A succussion splash could indicate the presence of ascites and obstruction.

- Any abnormalities discovered during the physical exam should prompt further investigation with imaging, such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or ultrasound, to evaluate for ascites, masses, or increased bowel gas due to ileus, obstruction, or pseudo-obstruction.

Radiologic imaging, laboratory testing and endoscopy

- An abdominal x-ray may reveal an increased stool burden, suggesting the need for further evaluation of slow transit constipation or a pelvic floor disorder, particularly in patients with functional constipation, IBS-mixed, or IBS-C.

- Hyperglycemia, weight gain, and bloating can be a presenting sign of ovarian cancer therefore all women should continue pelvic exams as dictated by the gynecologic societies. The need for an annual pelvic exam should be discussed with health care professionals especially in those with family history of ovarian cancer.

- An upper endoscopy may be warranted for patients over 40 years old with dyspeptic symptoms and abdominal bloating or distention, especially in regions with a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori.

- Chronic pancreatitis, indicated by bloating and pain, may necessitate fecal elastase testing to assess pancreatic function.

The expert review in the AGA clinical update provides step-by-step advice regarding the best practices6 for diagnosis and identifying who to test for ABD.

Treatment Options

The following sections highlight recent best practice advice on therapeutic approaches for treating ABD.

Dietary interventions

Specific foods may trigger bloating and abdominal distention, especially in patients with overlapping DGBIs. However, only a few studies have evaluated dietary restriction specifically for patients with primary ABD. Restricting non-absorbable sugars led to symptomatic improvement in 81% of patients with FABD who had documented sugar malabsorption.17 Two studies have shown that IBS patients treated with a low-fermentable, oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides (FODMAP) diet noted improvement in ABD and that restricting fructans initially may be the most optimal.18 A recent study showed that the Mediterranean diet improved IBS symptoms, including abdominal pain and bloating.19 It should be noted restrictive diets are efficacious but come with short- and long-term challenges. If empiric treatment and/or therapeutic testing do not resolve symptoms, a referral to a dietitian can be useful. Dietitians can provide tailored dietary advice, ensuring patients avoid trigger foods while maintaining a balanced and nutritious diet.

Prokinetics and laxatives

Prokinetic agents are used to treat symptoms of FD, gastroparesis, chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), and IBS. A meta-analysis of 13 trials found all constipation medications superior to placebo for treating abdominal bloating in patients with IBS-C.20

Probiotics

Treatment with probiotics is recommended for bloating or distention. One double-blind placebo-controlled trial with two separate probiotics, Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus acidophilus, showed improvements in global GI symptoms of patients with DGBI at 8 weeks versus placebo, with improvements in bloating symptoms.21

Antibiotics

The most commonly studied antibiotic for treating bloating is rifaximin.22 Global symptomatic improvement in IBS patients treated with antibiotics has correlated with the normalization of hydrogen levels in lactulose hydrogen breath tests.22 Patients with non-constipation IBS randomized to rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 14 days had a greater proportion of relief of IBS-related bloating compared to placebo for at least 2 of the first 4 weeks after treatment.22 Future research warrants use of narrow-spectrum antibiotics study for FABD as the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may deplete commensals forever, resulting in metabolic disorders.

Biofeedback therapy

Anorectal biofeedback therapy may help with ABD, particularly in patients with IBS-C and chronic constipation. One study noted that post-biofeedback therapy, myoelectric activity of the intercostals and diaphragm decreased, and internal oblique myoelectric activity increased.23 This study also showed ascent of the diaphragm and decreased girth, improving distention.

Central neuromodulators

As bloating results from multiple disturbed mechanisms, including altered gut-brain interaction, these symptoms can be amplified by psychological states such as anxiety, depression, or somatization. Central neuromodulators reduce the perception of visceral signals, re-regulate brain-gut control mechanisms, and improve psychological comorbidities.6 A large study of FD patients demonstrated that both amitriptyline (50 mg daily) and escitalopram (10 mg daily) significantly improved postprandial bloating compared to placebo.24 Antidepressants that activate noradrenergic and serotonergic pathways, including tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine and venlafaxine), show the greatest benefit in reducing visceral sensations.6

Brain-gut behavioral therapies

A recent multidisciplinary consensus report supports a myriad of potential brain-gut behavioral therapies (BGBTs) for treating DGBI.25 These therapies, including hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other modalities, may be combined with central neuromodulators and other GI treatments in a safe, noninvasive, and complementary fashion. BGBTs do not need to be symptom-specific, as they improve overall quality of life, anxiety, stress, and the burden associated with DGBIs. To date, none of the BGBTs have focused exclusively on FABD; however, prescription-based psychological therapies are now FDA-approved for use on smart apps, improving global symptoms that include bloating in IBS and FD.

Recent AGA clinical update best practices should be considered for the clinical care of patients with ABD.6

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

ABD are highly prevalent and significantly impact patients with various GI and metabolic disorders. Although our understanding of these symptoms is still evolving, evidence increasingly points to the dysregulation of the gut-brain axis and supports the application of the biopsychosocial model in treatment. This model addresses diet, motility, visceral sensitivity, pelvic floor disorders and psychosocial factors, providing a comprehensive approach to patient care.

Physician-scientists around the globe face numerous challenges when evaluating patients with these symptoms. However, the recent AGA clinical update on the best practice guidelines offers step-by-step diagnostic tests and treatment options to assist physicians in making informed decisions. . More comprehensive, large-scale, and longitudinal studies using metabolomics, capsule technologies for discovery of dysbiosis, mass spectrometry, and imaging data are needed to identify the exact contributors to disease pathogenesis, particularly those that can be targeted with pharmacologic agents. Collaborative work between gastroenterologists, dietitians, gut-brain behavioral therapists, endocrinologists, is crucial for clinical care of patients with ABD.

Careful attention to the patient’s primary symptoms and physical examination, combined with advancements in targeted diagnostics like the analysis of microbial markers, metabolites, and molecular signals, can significantly enhance patient clinical outcomes. Additionally, education and effective communication using a patient-centered care model are essential for guiding practical evaluation and individualized treatment.

Dr. Singh is assistant professor (research) at the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine. Dr. Moshiree is director of motility at Atrium Health, and clinical professor of medicine, Wake Forest Medical University, Charlotte, North Carolina.

References

1. Ballou S et al. Prevalence and associated factors of bloating: Results from the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 June. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049.

2. Oh JE et al. Abdominal bloating in the United States: Results of a survey of 88,795 Americans examining prevalence and healthcare seeking. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.031.

3. Drossman DA et al. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of gut-brain interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279.

4. Lacy BE et al. Management of chronic abdominal distension and bloating. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.056.

5. Mearin F et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031.

6. Moshiree B et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on evaluation and management of belching, abdominal bloating, and distention: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.039.

7. Viswanathan L and Rao SS. Intestinal disaccharidase deficiency in adults: evaluation and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2023 May. doi: 10.1007/s11894-023-00870-z.

8. Wilder-Smith CH et al. Fructose and lactose intolerance and malabsorption testing: the relationship with symptoms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jun. doi: 10.1111/apt.12306.

9. Skodje GI et al. Fructan, rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.040.

10. Singh R et al. Current treatment options and therapeutic insights for gastrointestinal dysmotility and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jan. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.808195.

11. Accarino A et al. Abdominal distention results from caudo-ventral redistribution of contents. Gastroenterology 2009 May. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.067.

12. Shim L et al. Prolonged balloon expulsion is predictive of abdominal distension in bloating. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Apr. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.54.

13. Villoria A et al. Abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia in patients with abdominal bloating and distension. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 May. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.408.

14. Neri L and Iovino P. Laxative Inadequate Relief Survey Group. Bloating is associated with worse quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and treatment responsiveness among patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12758.

15. Saffouri GB et al. Small intestinal microbial dysbiosis underlies symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Commun. 2019 May. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09964-7.

16. Villanueva-Millan MJ et al. Methanogens and hydrogen sulfide producing bacteria guide distinct gut microbe profiles and irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001997.

17. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Sugar malabsorption in functional abdominal bloating: a pilot study on the long-term effect of dietary treatment. Clin Nutr. 2006 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.010.

18. Böhn L et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.054.

19. Staudacher HM et al. Clinical trial: A Mediterranean diet is feasible and improves gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1111/apt.17791.

20. Nelson AD et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis: efficacy of licensed drugs for abdominal bloating in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1111/apt.16437.

21. Ringel-Kulka T et al. Probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders: a double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820ca4d6.

22. Pimentel M et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409.

23. Iovino P et al. Pelvic floor biofeedback is an effective treatment for severe bloating in disorders of gut-brain interaction with outlet dysfunction. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14264.

24. Talley NJ et al. Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: A multicenter, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.020.

25. Keefer L et al. A Rome Working Team Report on brain-gut behavior therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.015.

Introduction

Abdominal bloating is a common condition affecting up to 3.5% of people globally (4.6% in women and 2.4% in men),1 with 13.9% of the US population reporting bloating in the past 7 days.2 The prevalence of bloating and distention exceeds 50% when linked to disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs) such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), constipation, gastroparesis, and functional dyspepsia (FD).3,4 According to the Rome IV criteria, functional bloating and distention (FABD) patients are characterized by recurrent symptoms of abdominal fullness or pressure (bloating), or a visible increase in abdominal girth (distention) occurring at least 1 day per week for 3 consecutive months with an onset of 6 months and without predominant pain or altered bowel habits.5

Prolonged abdominal bloating and distention (ABD) can significantly impact quality of life and work productivity and can lead to increased medical consultations.2 Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms are involved in ABD that complicate the clinical management.4 There is an unmet need to understand the underlying mechanisms that lead to the development of ABD such as, food intolerance, abnormal viscerosomatic reflex, visceral hypersensitivity, and gut microbial dysbiosis. Recent advancements and acceptance of a multidisciplinary management of ABD have shifted the paradigm from merely treating symptoms to subtyping the condition and identifying overlaps with other DGBIs in order to individualize treatment that addresses the underlying pathophysiological mechanism. The recent American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) clinical update provided insights into the best practice advice for evaluating and managing ABD based on a review of current literature and on expert opinion of coauthors.6 This article aims to deliberate a practical approach to diagnostic strategies and treatment options based on etiology to refine clinical care of patients with ABD.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

ABD can result from various pathophysiological mechanisms. This section highlights the major causes (illustrated in Figure 1).

Food intolerances

Understanding food intolerances is crucial for diagnosing and managing patients with ABD. Disaccharidase deficiency is common (e.g., lactase deficiency is found in 35%-40% of adults).7 It can be undiagnosed in patients presenting with IBS symptoms, given the overlap in presentation with a prevalence of 9% of pan-disaccharidase deficiency. Sucrase-deficient patients must often adjust sugar and carbohydrate/starch intake to relieve symptoms.7 Deficiencies in lactase and sucrase activity, along with the consumption of some artificial sweeteners (e.g., sugar alcohols and sorbitol) and fructans can lead to bloating and distention. These substances increase osmotic load, fluid retention, microbial fermentation, and visceral hypersensitivity, leading to gas production and abdominal distention. One prospective study of symptomatic patients with various DGBIs (n = 1372) reported a prevalence of lactose intolerance and malabsorption at 51% and 32%, respectively.8 Furthermore, fructose intolerance and malabsorption prevalence were 60% and 45%, respectively.8 Notably, lactase deficiency does not always cause ABD, as not all individuals with lactase deficiency experience these symptoms after consuming lactose. Patients with celiac disease (CD), non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), and gluten intolerance can also experience bloating and distention, with or without changes in bowel habits.9 In some patients with self-reported NCGS, symptoms may be due to fructans in gluten-rich foods rather than gluten itself, thus recommending the elimination of fructans may help improve symptoms.9

Visceral hypersensitivity

Visceral hypersensitivity is explained by an increased perception of gut mechano-chemical stimulation, which typically manifests in an aggravated feeling of pain, nausea, distension, and ABD.10 In the gut, food particles and gut bacteria and their derived molecules interact with neuroimmune and enteroendocrine cells causing visceral sensitivity by the proximity of gut’s neurons to immune cells activated by them and leading to inflammatory reactions (Figure 1).

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Patients with anorectal motor dysfunction often experience difficulty in effectively evacuating both gas and stool, leading to ABD.12 Impaired ability to expel gas and stool results in prolonged balloon expulsion times, which correlates with symptoms of distention in patients with constipation.

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia is characterized as a paradoxical viscerosomatic reflex response to minimal gaseous distention in individuals with FABD.13 In this condition, the diaphragm contracts (descends), and the anterior abdominal wall muscles relax in response to the presence of gas. This response is opposite to the normal physiological response to increased intraluminal gas, where the diaphragm relaxes and the anterior abdominal muscles contract to increase the craniocaudal capacity of the abdominal cavity without causing abdominal protrusion.13 Patients with FABD exhibit significant abdominal wall protrusion and diaphragmatic descent even with relatively small increases in intraluminal gas.11 Understanding the role of abdominophrenic dyssynergia in abdominal bloating and distention is essential for effective diagnosis and management of the patients.

Gut dysmotility

Gut dysmotility is a crucial factor that can contribute to FABD. Gut dysmotility affects the movement of contents through the GI tract, accumulating gas and stool, directly contributing to bloating and distention. A prospective study involving over 2000 patients with functional constipation and constipation predominant-IBS (IBS-C) found that more than 90% of these patients reported symptoms of bloating.14 Furthermore, in IBS-C patients, those with prolonged colonic transit exhibited greater abdominal distention compared to those with normal gut transit times. In patients with gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying resulting in prolonged retention of stomach contents is the main factor in the generation of bloating symptoms.4

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO is overrepresented in various conditions, including IBS, FD, diabetes, gastrointestinal (GI) surgery patients and obesity, and can play an important role in generating ABD. Excess bacteria in the small intestine ferment carbohydrates, producing gas that stretches and distends the small intestine, leading to these symptoms. Additionally, altered sensation and abnormal viscerosomatic reflexes may contribute to SIBO-related bloating.4 One recent study noted decreased duodenal phylogenetic diversity in individuals who developed postprandial bloating.15 Increased methane levels caused by intestinal methanogen overgrowth, primarily the archaea Methanobrevibacter smithii, is possibly responsible for ABD in patients with IBS-C.16 Testing for SIBO in patients with ABD is generally only recommended if there are clear risk factors or severe symptoms warranting a test-and-treat approach.

Practical Diagnosis

Diagnosing ABD typically does not require extensive laboratory testing, imaging, or endoscopy unless there are alarm features or significant changes in symptoms. Here is the AGA clinical update on best practice advice6 for when to conduct further testing:

Diagnostic tests should be considered if patients exhibit:

- Recent onset or worsening of dyspepsia or abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- GI bleeding

- Unintentional weight loss exceeding 10% of body weight

- Chronic diarrhea

- Family history of GI malignancy, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease

Physical examination

If visible abdominal distention is present, a thorough abdominal examination can help identify potential issues:

- Tympany to percussion suggests bowel dilation.

- Abnormal bowel sounds may indicate obstruction or ileus.

- A succussion splash could indicate the presence of ascites and obstruction.

- Any abnormalities discovered during the physical exam should prompt further investigation with imaging, such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or ultrasound, to evaluate for ascites, masses, or increased bowel gas due to ileus, obstruction, or pseudo-obstruction.

Radiologic imaging, laboratory testing and endoscopy

- An abdominal x-ray may reveal an increased stool burden, suggesting the need for further evaluation of slow transit constipation or a pelvic floor disorder, particularly in patients with functional constipation, IBS-mixed, or IBS-C.

- Hyperglycemia, weight gain, and bloating can be a presenting sign of ovarian cancer therefore all women should continue pelvic exams as dictated by the gynecologic societies. The need for an annual pelvic exam should be discussed with health care professionals especially in those with family history of ovarian cancer.

- An upper endoscopy may be warranted for patients over 40 years old with dyspeptic symptoms and abdominal bloating or distention, especially in regions with a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori.

- Chronic pancreatitis, indicated by bloating and pain, may necessitate fecal elastase testing to assess pancreatic function.

The expert review in the AGA clinical update provides step-by-step advice regarding the best practices6 for diagnosis and identifying who to test for ABD.

Treatment Options

The following sections highlight recent best practice advice on therapeutic approaches for treating ABD.

Dietary interventions

Specific foods may trigger bloating and abdominal distention, especially in patients with overlapping DGBIs. However, only a few studies have evaluated dietary restriction specifically for patients with primary ABD. Restricting non-absorbable sugars led to symptomatic improvement in 81% of patients with FABD who had documented sugar malabsorption.17 Two studies have shown that IBS patients treated with a low-fermentable, oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides (FODMAP) diet noted improvement in ABD and that restricting fructans initially may be the most optimal.18 A recent study showed that the Mediterranean diet improved IBS symptoms, including abdominal pain and bloating.19 It should be noted restrictive diets are efficacious but come with short- and long-term challenges. If empiric treatment and/or therapeutic testing do not resolve symptoms, a referral to a dietitian can be useful. Dietitians can provide tailored dietary advice, ensuring patients avoid trigger foods while maintaining a balanced and nutritious diet.

Prokinetics and laxatives

Prokinetic agents are used to treat symptoms of FD, gastroparesis, chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), and IBS. A meta-analysis of 13 trials found all constipation medications superior to placebo for treating abdominal bloating in patients with IBS-C.20

Probiotics

Treatment with probiotics is recommended for bloating or distention. One double-blind placebo-controlled trial with two separate probiotics, Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus acidophilus, showed improvements in global GI symptoms of patients with DGBI at 8 weeks versus placebo, with improvements in bloating symptoms.21

Antibiotics

The most commonly studied antibiotic for treating bloating is rifaximin.22 Global symptomatic improvement in IBS patients treated with antibiotics has correlated with the normalization of hydrogen levels in lactulose hydrogen breath tests.22 Patients with non-constipation IBS randomized to rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 14 days had a greater proportion of relief of IBS-related bloating compared to placebo for at least 2 of the first 4 weeks after treatment.22 Future research warrants use of narrow-spectrum antibiotics study for FABD as the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may deplete commensals forever, resulting in metabolic disorders.

Biofeedback therapy

Anorectal biofeedback therapy may help with ABD, particularly in patients with IBS-C and chronic constipation. One study noted that post-biofeedback therapy, myoelectric activity of the intercostals and diaphragm decreased, and internal oblique myoelectric activity increased.23 This study also showed ascent of the diaphragm and decreased girth, improving distention.

Central neuromodulators

As bloating results from multiple disturbed mechanisms, including altered gut-brain interaction, these symptoms can be amplified by psychological states such as anxiety, depression, or somatization. Central neuromodulators reduce the perception of visceral signals, re-regulate brain-gut control mechanisms, and improve psychological comorbidities.6 A large study of FD patients demonstrated that both amitriptyline (50 mg daily) and escitalopram (10 mg daily) significantly improved postprandial bloating compared to placebo.24 Antidepressants that activate noradrenergic and serotonergic pathways, including tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine and venlafaxine), show the greatest benefit in reducing visceral sensations.6

Brain-gut behavioral therapies

A recent multidisciplinary consensus report supports a myriad of potential brain-gut behavioral therapies (BGBTs) for treating DGBI.25 These therapies, including hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other modalities, may be combined with central neuromodulators and other GI treatments in a safe, noninvasive, and complementary fashion. BGBTs do not need to be symptom-specific, as they improve overall quality of life, anxiety, stress, and the burden associated with DGBIs. To date, none of the BGBTs have focused exclusively on FABD; however, prescription-based psychological therapies are now FDA-approved for use on smart apps, improving global symptoms that include bloating in IBS and FD.

Recent AGA clinical update best practices should be considered for the clinical care of patients with ABD.6

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

ABD are highly prevalent and significantly impact patients with various GI and metabolic disorders. Although our understanding of these symptoms is still evolving, evidence increasingly points to the dysregulation of the gut-brain axis and supports the application of the biopsychosocial model in treatment. This model addresses diet, motility, visceral sensitivity, pelvic floor disorders and psychosocial factors, providing a comprehensive approach to patient care.

Physician-scientists around the globe face numerous challenges when evaluating patients with these symptoms. However, the recent AGA clinical update on the best practice guidelines offers step-by-step diagnostic tests and treatment options to assist physicians in making informed decisions. . More comprehensive, large-scale, and longitudinal studies using metabolomics, capsule technologies for discovery of dysbiosis, mass spectrometry, and imaging data are needed to identify the exact contributors to disease pathogenesis, particularly those that can be targeted with pharmacologic agents. Collaborative work between gastroenterologists, dietitians, gut-brain behavioral therapists, endocrinologists, is crucial for clinical care of patients with ABD.

Careful attention to the patient’s primary symptoms and physical examination, combined with advancements in targeted diagnostics like the analysis of microbial markers, metabolites, and molecular signals, can significantly enhance patient clinical outcomes. Additionally, education and effective communication using a patient-centered care model are essential for guiding practical evaluation and individualized treatment.

Dr. Singh is assistant professor (research) at the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine. Dr. Moshiree is director of motility at Atrium Health, and clinical professor of medicine, Wake Forest Medical University, Charlotte, North Carolina.

References

1. Ballou S et al. Prevalence and associated factors of bloating: Results from the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 June. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049.

2. Oh JE et al. Abdominal bloating in the United States: Results of a survey of 88,795 Americans examining prevalence and healthcare seeking. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.031.

3. Drossman DA et al. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of gut-brain interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279.

4. Lacy BE et al. Management of chronic abdominal distension and bloating. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.056.

5. Mearin F et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031.

6. Moshiree B et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on evaluation and management of belching, abdominal bloating, and distention: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.039.

7. Viswanathan L and Rao SS. Intestinal disaccharidase deficiency in adults: evaluation and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2023 May. doi: 10.1007/s11894-023-00870-z.

8. Wilder-Smith CH et al. Fructose and lactose intolerance and malabsorption testing: the relationship with symptoms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jun. doi: 10.1111/apt.12306.

9. Skodje GI et al. Fructan, rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.040.

10. Singh R et al. Current treatment options and therapeutic insights for gastrointestinal dysmotility and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jan. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.808195.

11. Accarino A et al. Abdominal distention results from caudo-ventral redistribution of contents. Gastroenterology 2009 May. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.067.

12. Shim L et al. Prolonged balloon expulsion is predictive of abdominal distension in bloating. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Apr. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.54.

13. Villoria A et al. Abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia in patients with abdominal bloating and distension. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 May. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.408.

14. Neri L and Iovino P. Laxative Inadequate Relief Survey Group. Bloating is associated with worse quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and treatment responsiveness among patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12758.

15. Saffouri GB et al. Small intestinal microbial dysbiosis underlies symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Commun. 2019 May. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09964-7.

16. Villanueva-Millan MJ et al. Methanogens and hydrogen sulfide producing bacteria guide distinct gut microbe profiles and irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001997.

17. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Sugar malabsorption in functional abdominal bloating: a pilot study on the long-term effect of dietary treatment. Clin Nutr. 2006 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.010.

18. Böhn L et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.054.

19. Staudacher HM et al. Clinical trial: A Mediterranean diet is feasible and improves gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1111/apt.17791.

20. Nelson AD et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis: efficacy of licensed drugs for abdominal bloating in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1111/apt.16437.

21. Ringel-Kulka T et al. Probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders: a double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820ca4d6.

22. Pimentel M et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409.

23. Iovino P et al. Pelvic floor biofeedback is an effective treatment for severe bloating in disorders of gut-brain interaction with outlet dysfunction. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14264.

24. Talley NJ et al. Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: A multicenter, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.020.

25. Keefer L et al. A Rome Working Team Report on brain-gut behavior therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.015.