User login

Can scribes boost FPs’ efficiency and job satisfaction?

ABSTRACT

Purpose Research in other medical specialties has shown that the addition of medical scribes to the clinical team enhances physicians’ practice experience and increases productivity. To date, literature on the implementation of scribes in primary care is limited. To determine the feasibility and benefits of implementing scribes in family medicine, we undertook a pilot mixed-method quality improvement (QI) study.

Methods In 2014, we incorporated 4 part-time scribes into an academic family medicine practice consisting of 7 physicians. We then measured, via survey and time-tracking data, the impact the scribes had on physician office hours and productivity, time spent on documentation, perceptions of work-life balance, and physician and patient satisfaction.

Results Six of the 7 faculty physicians participated. This study demonstrated that the use of scribes in a busy academic primary care practice substantially reduced the amount of time that family physicians spent on charting, improved work-life balance, and had good patient acceptance. Specifically, the physicians spent an average of 5.1 fewer hours/week (hrs/wk) on documentation, while various measures of productivity revealed increases ranging from 9.2% to 28.8%. Perhaps most important of all, when the results of the pilot study were annualized, they were projected to generate $168,600 per year—more than twice the $79,500 annual cost of 2 full-time equivalent scribes.

Surveys assessing work-life balance demonstrated improvement in the physicians’ perception of the administrative burden/paperwork related to practice and a decrease in their perception of the extent to which work encroached on their personal lives. In addition, survey data from 313 patients at the time of their ambulatory visit with a scribe present revealed a high level of comfort. Likewise, surveys completed by physicians after 55 clinical sessions (ie, blocks of consecutive, uninterrupted patient appointments; there are usually 2 sessions per day) revealed good to excellent ratings more than 90% of the time.

Conclusion In an outpatient family medicine clinic, the use of scribes substantially improved physicians’ efficiency, job satisfaction, and productivity without negatively impacting the patient experience.

While electronic medical records (EMRs) are important tools for improving patient care and communication, they bring with them an additional administrative burden for health care providers. In the emergency medicine literature, scribes have been reported to reduce that burden and improve clinicians’ productivity and satisfaction.1-4 Additionally, studies have reported increases in patient volume, generated billings, and provider morale, as well as decreases in emergency department (ED) lengths of stay.5 A recent review of the emergency medicine literature concluded that scribes have “the ability to allay the burden of documentation, improve throughput in the ED, and potentially enhance doctors’ satisfaction.”6

Similar benefits following scribe implementation have been reported in the literature of other specialties. A maternal-fetal medicine practice reported significant increases in generated billings and reimbursement.7 Increases in physician productivity and improvements in physician-patient interactions were reported in a cardiology clinic,8 and a urology practice reported high satisfaction and acceptance rates among both patients and physicians.9

Practice management literature and an article in The New York Times have anecdotally described the benefits of scribes in clinical practice10-12 with the latter noting that, “Physicians who use [scribes] say they feel liberated from the constant note-taking ...” and that “scribes have helped restore joy in the practice of medicine.”10

A small retrospective review that appeared in The Journal of Family Practice last year looked at the quality of scribes’ notes and found that they were rated slightly higher than physicians’ notes—at least for diabetes visits. However, it did not address the issues of physician productivity or satisfaction. (See "Medical scribes: How do their notes stack up?" 2016;65:155-159.)

The only family medicine study that we did find that addressed these 2 issues was one done in Oregon. The study noted that scribes enabled physicians to see 24 patients per day—up from 18, with accompanying improvements in physician “quality of life.”13 Absent from the literature are quantitative data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing scribes in family medicine.

Could a study at our facility offer some insights? In light of the paucity of published data on scribes in family medicine, and the fact that a survey conducted at our health center revealed that our faculty physicians felt overburdened by the administrative demands of clinical practice,14 we decided to study whether scribes might improve the work climate for clinicians at our family medicine residency training site. Our goal was to assess the impact of scribes on physician and patient satisfaction and on hours physicians spent on administrative tasks generated by clinical care.

METHODS

The study took place at the Barre Family Health Center (BFHC), a rural, freestanding family health center/residency site owned and operated by UMassMemorial Health Care (UMMHC), the major teaching/clinical affiliate of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The health care providers of BFHC conduct 40,000 patient visits annually. Without scribes, the physicians typically dictated their notes at the end of the day, and they became available for review/sign off usually within 24 hours.

Six of the 7 faculty physicians working at BFHC in 2014 (including the lead author) participated in the pilot study (the seventh declined to participate). Three male and 3 female physicians between the ages of 34 and 65 years participated; they had been in practice between 5 and 40 years. All of the physicians had used an EMR for 5 years or more, and all but 2 had previously used a paper record. Residents and advanced practitioners did not participate because limited funding allowed for the hiring of only 2 full-time equivalent (FTE; 4 part-time) scribes.

Contracting for services. We contracted with an outside vendor for scribe services. Prior to their arrival at our health care center, the scribes received online training on medical vocabulary, note structure, billing and coding, and patient confidentiality (HIPAA). Once they arrived, on-site training detailed workflow, precharting, use of templates, the EMR and chart organization, and billing. In addition to typing notes into the EMR during patient visits, the scribes helped develop processes for scheduling, alerting patients to the scribe’s role, and defining when scribes should and should not be present in the exam room. The chief scribe created a monthly schedule, which enabled staff to determine which physician schedules should have extra appointment slots added. This was imperative because our parent institution mandated that new initiatives yield a 25% return on investment (ROI).

Using standard scripting and consent methods, nursing staff informed patients during rooming that the provider was working with a scribe, explained the scribe’s role, and asked about any objections to the scribe’s presence. Patients could decline scribe involvement, and all scribes were routinely excused during genital and rectal examinations.

Data collection

Data were collected during the 6-month trial period from May through October of 2014. The number of hours physicians spent at BFHC and at home working on clinical documentation was collected using a smartphone time-tracking application for two 3-week periods: the first period was in April 2014, before the scribes came on board; the second period was at the end of the 6-month scribe implementation period. In order to assess effects on productivity and whether the project was meeting the required ROI for continuation, we included a retrospective review of the EMR for both of the 3-week periods to document total clinical hours, number of clinic sessions (blocks of consecutive, uninterrupted appointments), average hours per session, the number of patient appointments scheduled per session, and the number of patient visits actually conducted per session (accounting for no-shows and unused appointments).

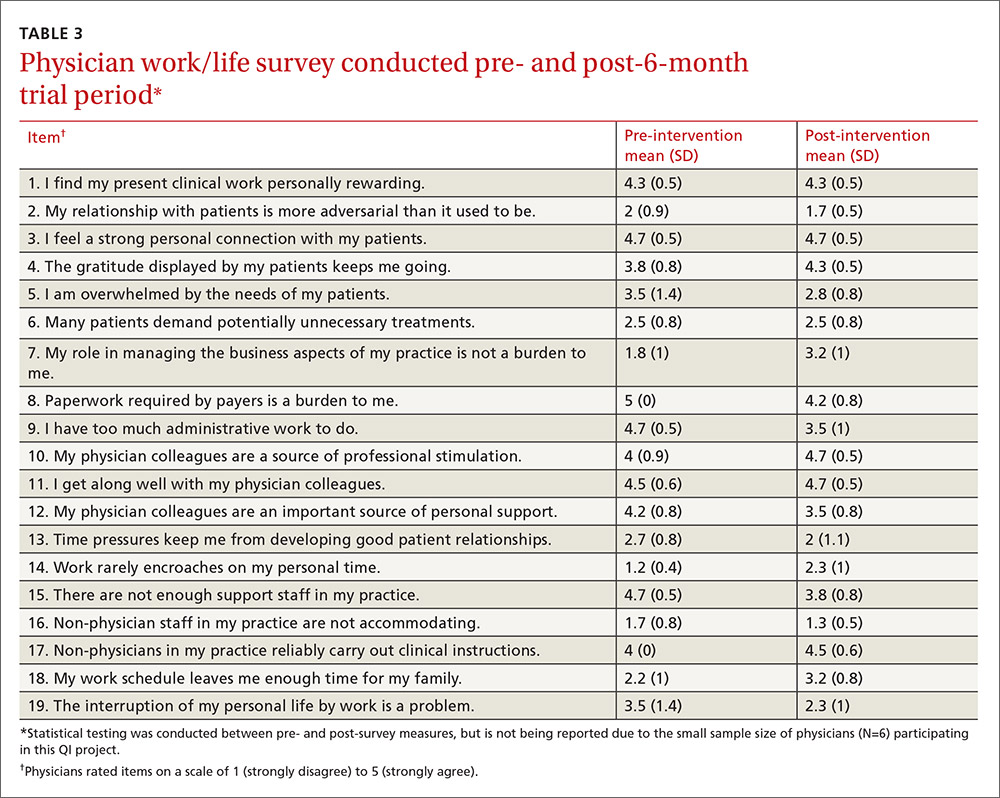

Physician work-life balance. We utilized 19 questions most relevant to this project’s focus from the 36-item Physician Work-Life Survey.15 Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). The BFHC ambulatory manager distributed surveys to physicians immediately prior to the trial with scribes and 2 weeks after the conclusion of the 6-month trial.

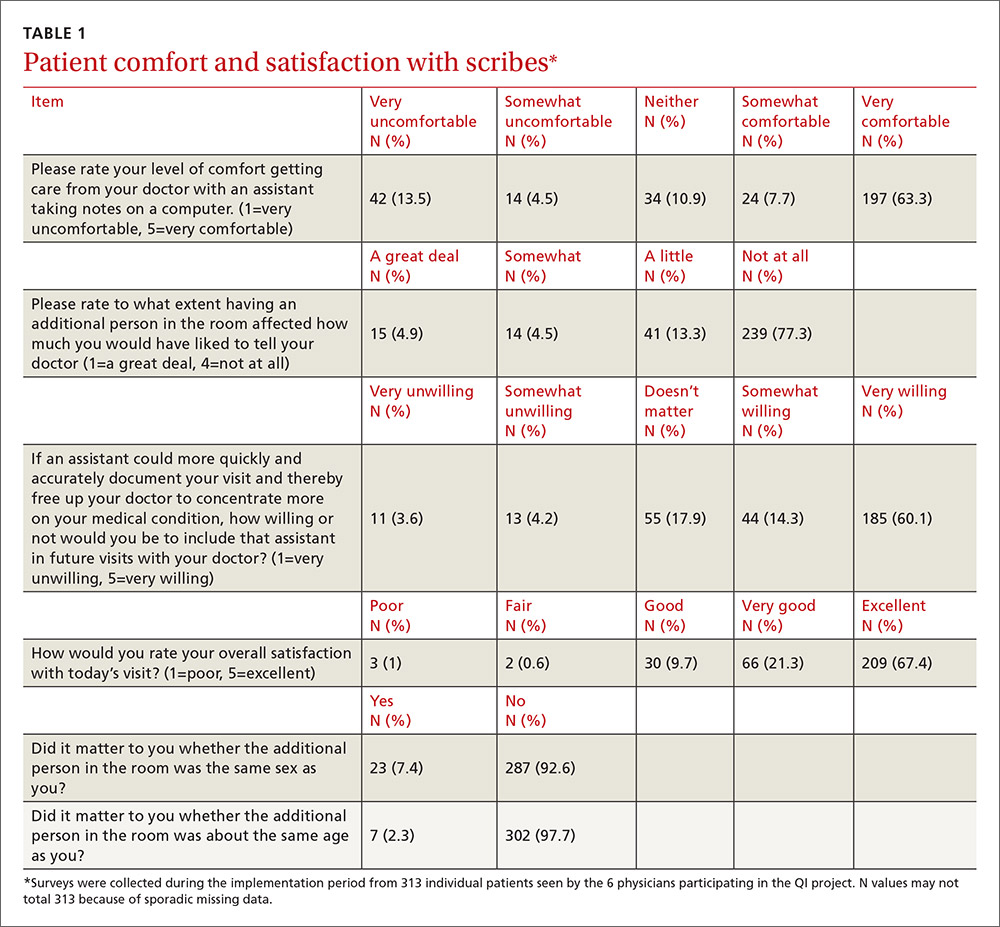

Patient and provider satisfaction. During the 6-month intervention period, satisfaction surveys9 were distributed to patients by scribes at the end of the office visit and to physicians at the end of each scribed session, after notes were completed and reviewed. Patient surveys consisted of 6 closed-end questions regarding comfort level with the scribe in the exam room, willingness to have a scribe present for subsequent visits, importance of the scribe being the same gender/age as the patient, and overall satisfaction with the scribe’s presence (TABLE 1).

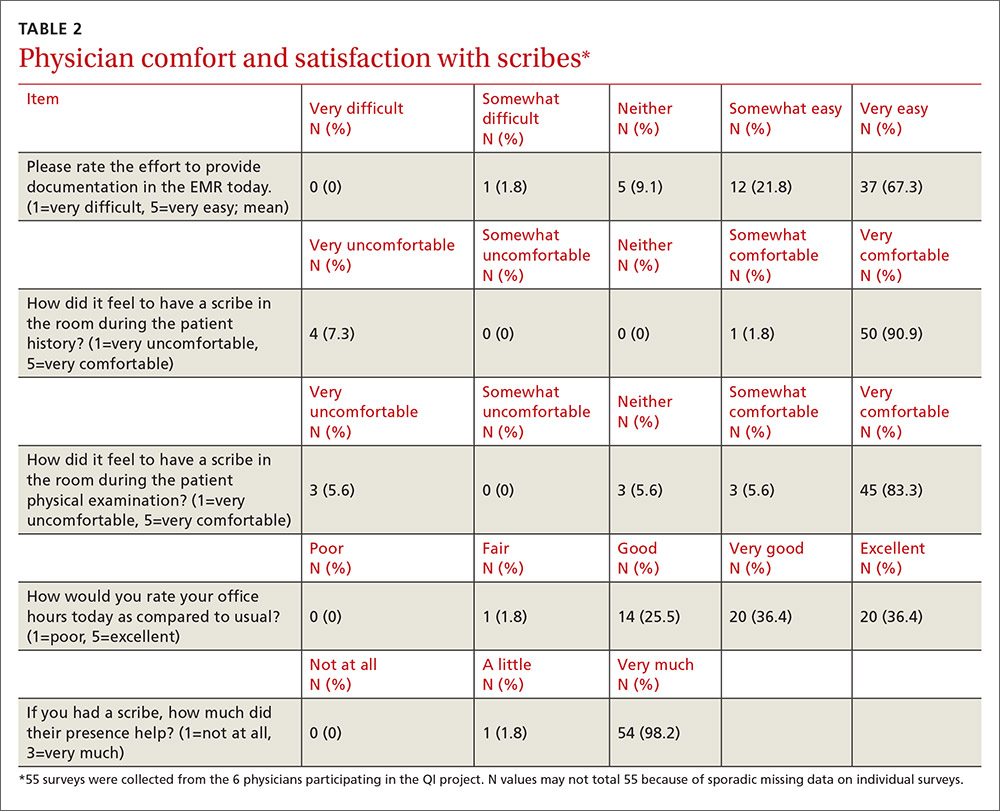

Physician surveys included 5 closed-end questions9 regarding comfort level with the scribe’s presence, ease of EMR documentation, change in office hours with having a scribe for that day’s session(s), and overall helpfulness of the scribe (TABLE 2). Open-ended questions on both surveys asked for additional comments or concerns regarding scribes and the scribe’s impact on patient encounters.

Our goal was to collect a minimum of 100 completed patient surveys and 50 completed physician surveys representing as many different patient demographics, visit types, days of the week, and times of day as possible. Surveys were anonymous and distributed during the second and third months of the trial, giving the scribes a one-month training and adjustment period.

Impact assessment, professional development needs. At the end of the 6-month study period, we held 2 focus groups—one with nurses and one with scribes. From the nurses, we solicited insights regarding the impact of scribes on patient volume, patient satisfaction, visit flow, and EMR documentation.

Scribes were asked about job skills needed, amount of training received, comfort in the exam room (both for themselves and patients), frequency of feedback received, balancing physician style with EMR documentation needs, and lessons learned.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the software SPSS V22.0. Univariate statistics were used to analyze patient and physician satisfaction, as well as clinic volume, time tracking, and EMR documentation. Initially, bivariate statistics were used to examine pre- and post-trial physician and patient data, but then non-parametric comparisons were used because of small sample sizes (and the resulting data being distributed abnormally). Detailed focus group notes were reviewed by all study investigators and summarized for dominant themes to support the quantitative evaluation. Lastly, the study was evaluated by the University of Massachusetts Institutional Review Board and was waived from review/oversight because of its QI intent.

RESULTS

Physician findings. Fifty-five physician surveys were completed during the 6-month period (TABLE 2). All of the physicians who were asked to complete this short survey at the end of the day (after reviewing notes with their scribe) did so. Physicians reported a high degree of satisfaction with collaboration with scribes. Their comments reflected positive experiences, including an improved ability to remain on schedule, having assistance finding important information in the record, and having notes completed at the end of the session.

TABLE 3 shows high satisfaction with clinical roles and colleagues with no substantive changes over time regarding these questions. However, the incorporation of scribes had a positive impact on issues related to physician morale, due to changes in paperwork, administrative duties, and work schedules.

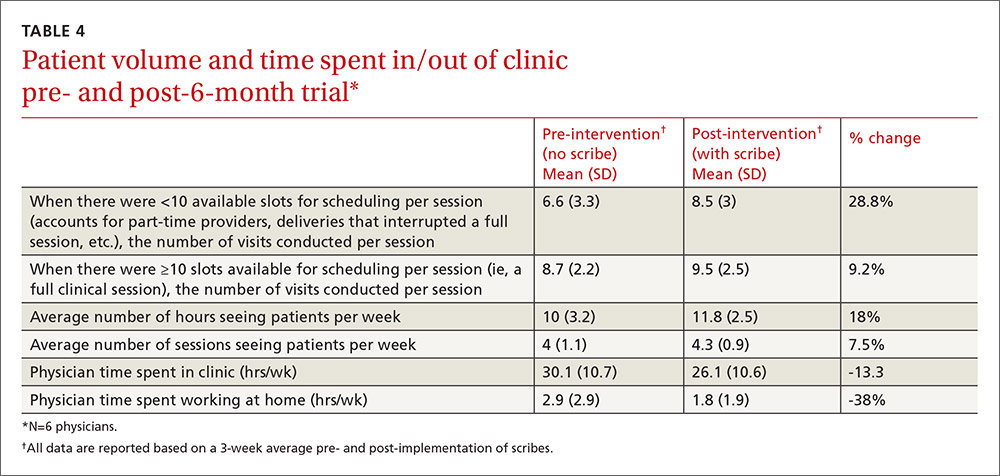

Review of patient scheduling and documentation (TABLE 4) revealed visits per clinical session increased 28.8% from 6.6 to 8.5, and for sessions with 10 or more appointment slots available, billable visits increased 9.2% from 8.7 to 9.5. This increase was a result of adding an additional appointment slot to the schedule when a scribe was assigned and a greater physician willingness to overbook when scribe assistance was available.

A comparison of time tracking pre- and post-intervention showed a 13% decrease in time spent in the clinic, from a 3-week average of 30.1 hrs/wk to 26.1 hrs/wk (TABLE 4). Time spent working at home decreased 38%, from a 3-week average of 2.9 hrs/wk to 1.8 hrs/wk. These reductions occurred despite average scheduled clinic hours being 18% higher (35.5 vs 30.1) during the post- vs pre-intervention measurement periods.

Patient findings. TABLE 1 summarizes the 313 patient responses. Less than 10% of patients declined to have a scribe during the visit. Patients reported a high level of comfort with the scribe and indicated that having a scribe in the room had little impact on what they would have liked to tell their doctor. Nearly all open-ended comments were positive and reflected feelings that the scribe’s presence enabled their provider to focus more on them and less on the computer.

Focus group findings

The scribe focus group identified a number of skills thought to be necessary to be successful in the job, including typing quickly; having technology/computer-searching strategy skills; and being detail-oriented, organized, and able to multitask. Scribes estimated that it took 2 to 6 weeks to feel comfortable doing the job. Physician feedback was preferred at the end of every session.

Lastly, the 4 scribes identified several challenges that should be addressed in future training, such as how to: 1. document a visit when the patient has a complicated medical history and the communication between the doctor and the patient is implicit; 2. incorporate the particulars of a visit into a patient’s full medical history; and 3. sift through the volume of previous notes when a physician has been seeing a patient for a long period of time.

The nurses’ focus group identified many positive effects on patient care. They reported no significant challenges with introducing scribes to patients. Improvements in timely availability of documentation enhanced their ability to respond quickly and more completely to patient queries. The nurses noted that the use of scribes improved patient care and made them “a better practice.”

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the use of scribes in a busy academic primary care practice substantially reduced the amount of time that family practitioners spent on charting, improved work-life balance, and had good patient acceptance. Our time-tracking studies demonstrated that physicians spent 5.1 fewer hrs/wk working—4 fewer hrs/wk in the clinic, and 1.1 fewer hrs/wk outside of the clinic—while clinical hours and productivity per session increased. Patients reported high satisfaction with scribed visits and a willingness to have scribes in the future. Creating notes in real time and having immediate availability after the session was a plus for nursing staff in providing follow-up patient care.

Concerns by physicians that having another person in the room would alter the physician-patient relationship were not substantiated, perhaps because the staff routinely obtained consent and explained the scribe’s role. Consistent with previous work, we found no suggestion that a scribe’s presence affected patients’ willingness to discuss sensitive issues.9 Patients reacted positively to scribes who enabled physicians to focus more on the patient and less on charting.

Despite increased patient volume, physician morale improved. Physicians left work more than an hour earlier per day, on average, and spent over 1 hour less per week working on clinical documentation outside the office. Physician surveys showed an improvement in perceptions of how much work encroached on their personal life, consistent with the time-tracking data. These results have significant implications for clinician retention, productivity, and satisfaction.

Since our site is an academic training site, one might wonder how residents and advanced practitioners viewed this implementation, as they were not initially included. From the perspective of the administrators, this was a feasibility study. Clinicians who were not included understood that if this pilot was successful, the use of scribes would be expanded in the future. In fact, because of these positive results, our institution has expanded the scribe program, so that it now covers all clinical sessions for faculty in our center and is rolling out a similar program in 3 other departmental academic practices.

Financial implications. At the beginning of this initiative, our institution required that we cover the cost of the program plus generate a 25% ROI. Using a conservative 9.2% increase in billable visits, we extrapolated that utilizing 2 FTE scribes would result in an additional 860 visits annually. Per our hospital’s finance department, estimated revenue generated by our facility-based practice per visit is $196, including ancillaries. That means that additional visits would generate an estimated $168,600 annually—more than twice the $79,500 annual cost of 2 FTE scribes, yielding a 112% ROI. Furthermore, patient access improved by making more visits available. Beyond the positive direct ROI, the improvements in physician morale and work-life balance have positive implications for retention, likely substantially increasing the long-term, overall ROI.

Challenges. Implementing a new program in a large organization proved to be challenging. The biggest hurdle was convincing our institution’s administration and finance department that this new expense would pay for itself in both tangible (increased visits per session) and intangible (increased physician satisfaction and retention) ways. A cost-sharing arrangement proposed by our department’s administrator convinced hospital administration to move forward. Additional challenges included delays in getting the scribe program started because of vendor selection, purchasing new laptops for scribes, hiring and training scribes, developing new EMR templates, validating provider productivity, and legal/compliance approval of the scribe’s EMR documentation processes to meet third-party and accuracy/quality requirements—all taking longer than anticipated. However, we believe that our results indicate significant potential for other primary care practices.

Limitations. The number of physicians in the study was small, and they all worked in the same location. Social desirability could have biased patient and provider feedback, but our quantitative results were consistent with subjective assessments, suggesting that information bias potential was low. Patient and provider survey findings were also supported by qualitative assessments from both scribes and nursing staff. The size of the project did not lend itself to an analysis controlling for clustering by physician and/or scribe. The focus group discussions were not subject to rigorous qualitative analysis, potentially increasing the risk of biased interpretation. Lastly, we did not have the ability to directly compare sessions with and without scribes during the pilot.

Similarity to other findings. Despite these limitations, our findings are remarkably similar to those of Howard, et al,16 on the pilot implementation of scribes in a community health center, including good patient and clinician acceptance and increased productivity that more than offset the cost of the scribes. We expect that others implementing scribe services in primary care settings will experience similar results.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen T. Earls, MD, 151 Worcester Road, Barre, MA 01005; stephen.earls@umassmemorial.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Barbara Fisher, MBA, vice president for ambulatory services; Nicholas Comeau, BS; and Brenda Rivard, administrative lead, Barre Family Health Center, UMassMemorial Health Care, in the preparation and execution of this study.

1. Walker K, Ben-Meir M, O’Mullane P, et al. Scribes in an Australian private emergency department: a description of physician productivity. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:543-548.

2. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

3. Expanded scribe role boosts staff morale. ED Manag. 2009;21:75-77.

4. Scribes, EMR please docs, save $600,000. ED Manag. 2009;21:117-118.

5. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:399-402.

6. Cabilan CJ, Eley RM. Review article: potential of medical scribes to allay the burden of documentation and enhance efficiency in Australian emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 2015 Aug 13. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Hegstrom L, Leslie J, Hutchinson E, et al. Medical scribes: are scribe programs cost effective in an outpatient MFM setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:S240.

8. Campbell LL, Case D, Crocker JE, et al. Using medical scribes in a physician practice. J AHIMA. 2012;83:64-69.

9. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, et al. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184:258-262.

10. Hafner K. A busy doctor’s right hand, ever ready to type. The New York Times. January 12, 2014. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/14/health/a-busy-doctors-right-hand-ever-ready-to-type.html?_r=0. Accessed February 6, 2017.

11. Brady K, Shariff A. Virtual medical scribes: making electronic medical records work for you. J Med Pract Manage. 2013;29:133-136.

12. Baugh R, Jones JE, Troff K, et al. Medical scribes. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28:195-197.

13. Grimshaw H. Physician scribes improve productivity. Oak Street Medical allows doctors to spend more face time with patients, improve job satisfaction. MGMA Connex. 2012;12:27-28.

14. Morehead Associates, Inc. UMassMemorial Health Care: Physician Satisfaction Survey. 2013.

15. Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, et al. Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37:1174-1182.

16. Howard KA, Helé K, Salibi N, et al. BTW Informing change. Blue Shield of California Foundation. Adapting the EHR scribe model to community health centers: the experience of Shasta Community Health Center’s pilot. Available at: http://informingchange.com/cat-publications/adapting-the-ehr-scribe-model-to-community-health-centers-the-experience-of-shasta-community-health-centers-pilot. Accessed November 6, 2015.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Research in other medical specialties has shown that the addition of medical scribes to the clinical team enhances physicians’ practice experience and increases productivity. To date, literature on the implementation of scribes in primary care is limited. To determine the feasibility and benefits of implementing scribes in family medicine, we undertook a pilot mixed-method quality improvement (QI) study.

Methods In 2014, we incorporated 4 part-time scribes into an academic family medicine practice consisting of 7 physicians. We then measured, via survey and time-tracking data, the impact the scribes had on physician office hours and productivity, time spent on documentation, perceptions of work-life balance, and physician and patient satisfaction.

Results Six of the 7 faculty physicians participated. This study demonstrated that the use of scribes in a busy academic primary care practice substantially reduced the amount of time that family physicians spent on charting, improved work-life balance, and had good patient acceptance. Specifically, the physicians spent an average of 5.1 fewer hours/week (hrs/wk) on documentation, while various measures of productivity revealed increases ranging from 9.2% to 28.8%. Perhaps most important of all, when the results of the pilot study were annualized, they were projected to generate $168,600 per year—more than twice the $79,500 annual cost of 2 full-time equivalent scribes.

Surveys assessing work-life balance demonstrated improvement in the physicians’ perception of the administrative burden/paperwork related to practice and a decrease in their perception of the extent to which work encroached on their personal lives. In addition, survey data from 313 patients at the time of their ambulatory visit with a scribe present revealed a high level of comfort. Likewise, surveys completed by physicians after 55 clinical sessions (ie, blocks of consecutive, uninterrupted patient appointments; there are usually 2 sessions per day) revealed good to excellent ratings more than 90% of the time.

Conclusion In an outpatient family medicine clinic, the use of scribes substantially improved physicians’ efficiency, job satisfaction, and productivity without negatively impacting the patient experience.

While electronic medical records (EMRs) are important tools for improving patient care and communication, they bring with them an additional administrative burden for health care providers. In the emergency medicine literature, scribes have been reported to reduce that burden and improve clinicians’ productivity and satisfaction.1-4 Additionally, studies have reported increases in patient volume, generated billings, and provider morale, as well as decreases in emergency department (ED) lengths of stay.5 A recent review of the emergency medicine literature concluded that scribes have “the ability to allay the burden of documentation, improve throughput in the ED, and potentially enhance doctors’ satisfaction.”6

Similar benefits following scribe implementation have been reported in the literature of other specialties. A maternal-fetal medicine practice reported significant increases in generated billings and reimbursement.7 Increases in physician productivity and improvements in physician-patient interactions were reported in a cardiology clinic,8 and a urology practice reported high satisfaction and acceptance rates among both patients and physicians.9

Practice management literature and an article in The New York Times have anecdotally described the benefits of scribes in clinical practice10-12 with the latter noting that, “Physicians who use [scribes] say they feel liberated from the constant note-taking ...” and that “scribes have helped restore joy in the practice of medicine.”10

A small retrospective review that appeared in The Journal of Family Practice last year looked at the quality of scribes’ notes and found that they were rated slightly higher than physicians’ notes—at least for diabetes visits. However, it did not address the issues of physician productivity or satisfaction. (See "Medical scribes: How do their notes stack up?" 2016;65:155-159.)

The only family medicine study that we did find that addressed these 2 issues was one done in Oregon. The study noted that scribes enabled physicians to see 24 patients per day—up from 18, with accompanying improvements in physician “quality of life.”13 Absent from the literature are quantitative data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing scribes in family medicine.

Could a study at our facility offer some insights? In light of the paucity of published data on scribes in family medicine, and the fact that a survey conducted at our health center revealed that our faculty physicians felt overburdened by the administrative demands of clinical practice,14 we decided to study whether scribes might improve the work climate for clinicians at our family medicine residency training site. Our goal was to assess the impact of scribes on physician and patient satisfaction and on hours physicians spent on administrative tasks generated by clinical care.

METHODS

The study took place at the Barre Family Health Center (BFHC), a rural, freestanding family health center/residency site owned and operated by UMassMemorial Health Care (UMMHC), the major teaching/clinical affiliate of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The health care providers of BFHC conduct 40,000 patient visits annually. Without scribes, the physicians typically dictated their notes at the end of the day, and they became available for review/sign off usually within 24 hours.

Six of the 7 faculty physicians working at BFHC in 2014 (including the lead author) participated in the pilot study (the seventh declined to participate). Three male and 3 female physicians between the ages of 34 and 65 years participated; they had been in practice between 5 and 40 years. All of the physicians had used an EMR for 5 years or more, and all but 2 had previously used a paper record. Residents and advanced practitioners did not participate because limited funding allowed for the hiring of only 2 full-time equivalent (FTE; 4 part-time) scribes.

Contracting for services. We contracted with an outside vendor for scribe services. Prior to their arrival at our health care center, the scribes received online training on medical vocabulary, note structure, billing and coding, and patient confidentiality (HIPAA). Once they arrived, on-site training detailed workflow, precharting, use of templates, the EMR and chart organization, and billing. In addition to typing notes into the EMR during patient visits, the scribes helped develop processes for scheduling, alerting patients to the scribe’s role, and defining when scribes should and should not be present in the exam room. The chief scribe created a monthly schedule, which enabled staff to determine which physician schedules should have extra appointment slots added. This was imperative because our parent institution mandated that new initiatives yield a 25% return on investment (ROI).

Using standard scripting and consent methods, nursing staff informed patients during rooming that the provider was working with a scribe, explained the scribe’s role, and asked about any objections to the scribe’s presence. Patients could decline scribe involvement, and all scribes were routinely excused during genital and rectal examinations.

Data collection

Data were collected during the 6-month trial period from May through October of 2014. The number of hours physicians spent at BFHC and at home working on clinical documentation was collected using a smartphone time-tracking application for two 3-week periods: the first period was in April 2014, before the scribes came on board; the second period was at the end of the 6-month scribe implementation period. In order to assess effects on productivity and whether the project was meeting the required ROI for continuation, we included a retrospective review of the EMR for both of the 3-week periods to document total clinical hours, number of clinic sessions (blocks of consecutive, uninterrupted appointments), average hours per session, the number of patient appointments scheduled per session, and the number of patient visits actually conducted per session (accounting for no-shows and unused appointments).

Physician work-life balance. We utilized 19 questions most relevant to this project’s focus from the 36-item Physician Work-Life Survey.15 Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). The BFHC ambulatory manager distributed surveys to physicians immediately prior to the trial with scribes and 2 weeks after the conclusion of the 6-month trial.

Patient and provider satisfaction. During the 6-month intervention period, satisfaction surveys9 were distributed to patients by scribes at the end of the office visit and to physicians at the end of each scribed session, after notes were completed and reviewed. Patient surveys consisted of 6 closed-end questions regarding comfort level with the scribe in the exam room, willingness to have a scribe present for subsequent visits, importance of the scribe being the same gender/age as the patient, and overall satisfaction with the scribe’s presence (TABLE 1).

Physician surveys included 5 closed-end questions9 regarding comfort level with the scribe’s presence, ease of EMR documentation, change in office hours with having a scribe for that day’s session(s), and overall helpfulness of the scribe (TABLE 2). Open-ended questions on both surveys asked for additional comments or concerns regarding scribes and the scribe’s impact on patient encounters.

Our goal was to collect a minimum of 100 completed patient surveys and 50 completed physician surveys representing as many different patient demographics, visit types, days of the week, and times of day as possible. Surveys were anonymous and distributed during the second and third months of the trial, giving the scribes a one-month training and adjustment period.

Impact assessment, professional development needs. At the end of the 6-month study period, we held 2 focus groups—one with nurses and one with scribes. From the nurses, we solicited insights regarding the impact of scribes on patient volume, patient satisfaction, visit flow, and EMR documentation.

Scribes were asked about job skills needed, amount of training received, comfort in the exam room (both for themselves and patients), frequency of feedback received, balancing physician style with EMR documentation needs, and lessons learned.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the software SPSS V22.0. Univariate statistics were used to analyze patient and physician satisfaction, as well as clinic volume, time tracking, and EMR documentation. Initially, bivariate statistics were used to examine pre- and post-trial physician and patient data, but then non-parametric comparisons were used because of small sample sizes (and the resulting data being distributed abnormally). Detailed focus group notes were reviewed by all study investigators and summarized for dominant themes to support the quantitative evaluation. Lastly, the study was evaluated by the University of Massachusetts Institutional Review Board and was waived from review/oversight because of its QI intent.

RESULTS

Physician findings. Fifty-five physician surveys were completed during the 6-month period (TABLE 2). All of the physicians who were asked to complete this short survey at the end of the day (after reviewing notes with their scribe) did so. Physicians reported a high degree of satisfaction with collaboration with scribes. Their comments reflected positive experiences, including an improved ability to remain on schedule, having assistance finding important information in the record, and having notes completed at the end of the session.

TABLE 3 shows high satisfaction with clinical roles and colleagues with no substantive changes over time regarding these questions. However, the incorporation of scribes had a positive impact on issues related to physician morale, due to changes in paperwork, administrative duties, and work schedules.

Review of patient scheduling and documentation (TABLE 4) revealed visits per clinical session increased 28.8% from 6.6 to 8.5, and for sessions with 10 or more appointment slots available, billable visits increased 9.2% from 8.7 to 9.5. This increase was a result of adding an additional appointment slot to the schedule when a scribe was assigned and a greater physician willingness to overbook when scribe assistance was available.

A comparison of time tracking pre- and post-intervention showed a 13% decrease in time spent in the clinic, from a 3-week average of 30.1 hrs/wk to 26.1 hrs/wk (TABLE 4). Time spent working at home decreased 38%, from a 3-week average of 2.9 hrs/wk to 1.8 hrs/wk. These reductions occurred despite average scheduled clinic hours being 18% higher (35.5 vs 30.1) during the post- vs pre-intervention measurement periods.

Patient findings. TABLE 1 summarizes the 313 patient responses. Less than 10% of patients declined to have a scribe during the visit. Patients reported a high level of comfort with the scribe and indicated that having a scribe in the room had little impact on what they would have liked to tell their doctor. Nearly all open-ended comments were positive and reflected feelings that the scribe’s presence enabled their provider to focus more on them and less on the computer.

Focus group findings

The scribe focus group identified a number of skills thought to be necessary to be successful in the job, including typing quickly; having technology/computer-searching strategy skills; and being detail-oriented, organized, and able to multitask. Scribes estimated that it took 2 to 6 weeks to feel comfortable doing the job. Physician feedback was preferred at the end of every session.

Lastly, the 4 scribes identified several challenges that should be addressed in future training, such as how to: 1. document a visit when the patient has a complicated medical history and the communication between the doctor and the patient is implicit; 2. incorporate the particulars of a visit into a patient’s full medical history; and 3. sift through the volume of previous notes when a physician has been seeing a patient for a long period of time.

The nurses’ focus group identified many positive effects on patient care. They reported no significant challenges with introducing scribes to patients. Improvements in timely availability of documentation enhanced their ability to respond quickly and more completely to patient queries. The nurses noted that the use of scribes improved patient care and made them “a better practice.”

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the use of scribes in a busy academic primary care practice substantially reduced the amount of time that family practitioners spent on charting, improved work-life balance, and had good patient acceptance. Our time-tracking studies demonstrated that physicians spent 5.1 fewer hrs/wk working—4 fewer hrs/wk in the clinic, and 1.1 fewer hrs/wk outside of the clinic—while clinical hours and productivity per session increased. Patients reported high satisfaction with scribed visits and a willingness to have scribes in the future. Creating notes in real time and having immediate availability after the session was a plus for nursing staff in providing follow-up patient care.

Concerns by physicians that having another person in the room would alter the physician-patient relationship were not substantiated, perhaps because the staff routinely obtained consent and explained the scribe’s role. Consistent with previous work, we found no suggestion that a scribe’s presence affected patients’ willingness to discuss sensitive issues.9 Patients reacted positively to scribes who enabled physicians to focus more on the patient and less on charting.

Despite increased patient volume, physician morale improved. Physicians left work more than an hour earlier per day, on average, and spent over 1 hour less per week working on clinical documentation outside the office. Physician surveys showed an improvement in perceptions of how much work encroached on their personal life, consistent with the time-tracking data. These results have significant implications for clinician retention, productivity, and satisfaction.

Since our site is an academic training site, one might wonder how residents and advanced practitioners viewed this implementation, as they were not initially included. From the perspective of the administrators, this was a feasibility study. Clinicians who were not included understood that if this pilot was successful, the use of scribes would be expanded in the future. In fact, because of these positive results, our institution has expanded the scribe program, so that it now covers all clinical sessions for faculty in our center and is rolling out a similar program in 3 other departmental academic practices.

Financial implications. At the beginning of this initiative, our institution required that we cover the cost of the program plus generate a 25% ROI. Using a conservative 9.2% increase in billable visits, we extrapolated that utilizing 2 FTE scribes would result in an additional 860 visits annually. Per our hospital’s finance department, estimated revenue generated by our facility-based practice per visit is $196, including ancillaries. That means that additional visits would generate an estimated $168,600 annually—more than twice the $79,500 annual cost of 2 FTE scribes, yielding a 112% ROI. Furthermore, patient access improved by making more visits available. Beyond the positive direct ROI, the improvements in physician morale and work-life balance have positive implications for retention, likely substantially increasing the long-term, overall ROI.

Challenges. Implementing a new program in a large organization proved to be challenging. The biggest hurdle was convincing our institution’s administration and finance department that this new expense would pay for itself in both tangible (increased visits per session) and intangible (increased physician satisfaction and retention) ways. A cost-sharing arrangement proposed by our department’s administrator convinced hospital administration to move forward. Additional challenges included delays in getting the scribe program started because of vendor selection, purchasing new laptops for scribes, hiring and training scribes, developing new EMR templates, validating provider productivity, and legal/compliance approval of the scribe’s EMR documentation processes to meet third-party and accuracy/quality requirements—all taking longer than anticipated. However, we believe that our results indicate significant potential for other primary care practices.

Limitations. The number of physicians in the study was small, and they all worked in the same location. Social desirability could have biased patient and provider feedback, but our quantitative results were consistent with subjective assessments, suggesting that information bias potential was low. Patient and provider survey findings were also supported by qualitative assessments from both scribes and nursing staff. The size of the project did not lend itself to an analysis controlling for clustering by physician and/or scribe. The focus group discussions were not subject to rigorous qualitative analysis, potentially increasing the risk of biased interpretation. Lastly, we did not have the ability to directly compare sessions with and without scribes during the pilot.

Similarity to other findings. Despite these limitations, our findings are remarkably similar to those of Howard, et al,16 on the pilot implementation of scribes in a community health center, including good patient and clinician acceptance and increased productivity that more than offset the cost of the scribes. We expect that others implementing scribe services in primary care settings will experience similar results.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen T. Earls, MD, 151 Worcester Road, Barre, MA 01005; stephen.earls@umassmemorial.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Barbara Fisher, MBA, vice president for ambulatory services; Nicholas Comeau, BS; and Brenda Rivard, administrative lead, Barre Family Health Center, UMassMemorial Health Care, in the preparation and execution of this study.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Research in other medical specialties has shown that the addition of medical scribes to the clinical team enhances physicians’ practice experience and increases productivity. To date, literature on the implementation of scribes in primary care is limited. To determine the feasibility and benefits of implementing scribes in family medicine, we undertook a pilot mixed-method quality improvement (QI) study.

Methods In 2014, we incorporated 4 part-time scribes into an academic family medicine practice consisting of 7 physicians. We then measured, via survey and time-tracking data, the impact the scribes had on physician office hours and productivity, time spent on documentation, perceptions of work-life balance, and physician and patient satisfaction.

Results Six of the 7 faculty physicians participated. This study demonstrated that the use of scribes in a busy academic primary care practice substantially reduced the amount of time that family physicians spent on charting, improved work-life balance, and had good patient acceptance. Specifically, the physicians spent an average of 5.1 fewer hours/week (hrs/wk) on documentation, while various measures of productivity revealed increases ranging from 9.2% to 28.8%. Perhaps most important of all, when the results of the pilot study were annualized, they were projected to generate $168,600 per year—more than twice the $79,500 annual cost of 2 full-time equivalent scribes.

Surveys assessing work-life balance demonstrated improvement in the physicians’ perception of the administrative burden/paperwork related to practice and a decrease in their perception of the extent to which work encroached on their personal lives. In addition, survey data from 313 patients at the time of their ambulatory visit with a scribe present revealed a high level of comfort. Likewise, surveys completed by physicians after 55 clinical sessions (ie, blocks of consecutive, uninterrupted patient appointments; there are usually 2 sessions per day) revealed good to excellent ratings more than 90% of the time.

Conclusion In an outpatient family medicine clinic, the use of scribes substantially improved physicians’ efficiency, job satisfaction, and productivity without negatively impacting the patient experience.

While electronic medical records (EMRs) are important tools for improving patient care and communication, they bring with them an additional administrative burden for health care providers. In the emergency medicine literature, scribes have been reported to reduce that burden and improve clinicians’ productivity and satisfaction.1-4 Additionally, studies have reported increases in patient volume, generated billings, and provider morale, as well as decreases in emergency department (ED) lengths of stay.5 A recent review of the emergency medicine literature concluded that scribes have “the ability to allay the burden of documentation, improve throughput in the ED, and potentially enhance doctors’ satisfaction.”6

Similar benefits following scribe implementation have been reported in the literature of other specialties. A maternal-fetal medicine practice reported significant increases in generated billings and reimbursement.7 Increases in physician productivity and improvements in physician-patient interactions were reported in a cardiology clinic,8 and a urology practice reported high satisfaction and acceptance rates among both patients and physicians.9

Practice management literature and an article in The New York Times have anecdotally described the benefits of scribes in clinical practice10-12 with the latter noting that, “Physicians who use [scribes] say they feel liberated from the constant note-taking ...” and that “scribes have helped restore joy in the practice of medicine.”10

A small retrospective review that appeared in The Journal of Family Practice last year looked at the quality of scribes’ notes and found that they were rated slightly higher than physicians’ notes—at least for diabetes visits. However, it did not address the issues of physician productivity or satisfaction. (See "Medical scribes: How do their notes stack up?" 2016;65:155-159.)

The only family medicine study that we did find that addressed these 2 issues was one done in Oregon. The study noted that scribes enabled physicians to see 24 patients per day—up from 18, with accompanying improvements in physician “quality of life.”13 Absent from the literature are quantitative data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing scribes in family medicine.

Could a study at our facility offer some insights? In light of the paucity of published data on scribes in family medicine, and the fact that a survey conducted at our health center revealed that our faculty physicians felt overburdened by the administrative demands of clinical practice,14 we decided to study whether scribes might improve the work climate for clinicians at our family medicine residency training site. Our goal was to assess the impact of scribes on physician and patient satisfaction and on hours physicians spent on administrative tasks generated by clinical care.

METHODS

The study took place at the Barre Family Health Center (BFHC), a rural, freestanding family health center/residency site owned and operated by UMassMemorial Health Care (UMMHC), the major teaching/clinical affiliate of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The health care providers of BFHC conduct 40,000 patient visits annually. Without scribes, the physicians typically dictated their notes at the end of the day, and they became available for review/sign off usually within 24 hours.

Six of the 7 faculty physicians working at BFHC in 2014 (including the lead author) participated in the pilot study (the seventh declined to participate). Three male and 3 female physicians between the ages of 34 and 65 years participated; they had been in practice between 5 and 40 years. All of the physicians had used an EMR for 5 years or more, and all but 2 had previously used a paper record. Residents and advanced practitioners did not participate because limited funding allowed for the hiring of only 2 full-time equivalent (FTE; 4 part-time) scribes.

Contracting for services. We contracted with an outside vendor for scribe services. Prior to their arrival at our health care center, the scribes received online training on medical vocabulary, note structure, billing and coding, and patient confidentiality (HIPAA). Once they arrived, on-site training detailed workflow, precharting, use of templates, the EMR and chart organization, and billing. In addition to typing notes into the EMR during patient visits, the scribes helped develop processes for scheduling, alerting patients to the scribe’s role, and defining when scribes should and should not be present in the exam room. The chief scribe created a monthly schedule, which enabled staff to determine which physician schedules should have extra appointment slots added. This was imperative because our parent institution mandated that new initiatives yield a 25% return on investment (ROI).

Using standard scripting and consent methods, nursing staff informed patients during rooming that the provider was working with a scribe, explained the scribe’s role, and asked about any objections to the scribe’s presence. Patients could decline scribe involvement, and all scribes were routinely excused during genital and rectal examinations.

Data collection

Data were collected during the 6-month trial period from May through October of 2014. The number of hours physicians spent at BFHC and at home working on clinical documentation was collected using a smartphone time-tracking application for two 3-week periods: the first period was in April 2014, before the scribes came on board; the second period was at the end of the 6-month scribe implementation period. In order to assess effects on productivity and whether the project was meeting the required ROI for continuation, we included a retrospective review of the EMR for both of the 3-week periods to document total clinical hours, number of clinic sessions (blocks of consecutive, uninterrupted appointments), average hours per session, the number of patient appointments scheduled per session, and the number of patient visits actually conducted per session (accounting for no-shows and unused appointments).

Physician work-life balance. We utilized 19 questions most relevant to this project’s focus from the 36-item Physician Work-Life Survey.15 Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). The BFHC ambulatory manager distributed surveys to physicians immediately prior to the trial with scribes and 2 weeks after the conclusion of the 6-month trial.

Patient and provider satisfaction. During the 6-month intervention period, satisfaction surveys9 were distributed to patients by scribes at the end of the office visit and to physicians at the end of each scribed session, after notes were completed and reviewed. Patient surveys consisted of 6 closed-end questions regarding comfort level with the scribe in the exam room, willingness to have a scribe present for subsequent visits, importance of the scribe being the same gender/age as the patient, and overall satisfaction with the scribe’s presence (TABLE 1).

Physician surveys included 5 closed-end questions9 regarding comfort level with the scribe’s presence, ease of EMR documentation, change in office hours with having a scribe for that day’s session(s), and overall helpfulness of the scribe (TABLE 2). Open-ended questions on both surveys asked for additional comments or concerns regarding scribes and the scribe’s impact on patient encounters.

Our goal was to collect a minimum of 100 completed patient surveys and 50 completed physician surveys representing as many different patient demographics, visit types, days of the week, and times of day as possible. Surveys were anonymous and distributed during the second and third months of the trial, giving the scribes a one-month training and adjustment period.

Impact assessment, professional development needs. At the end of the 6-month study period, we held 2 focus groups—one with nurses and one with scribes. From the nurses, we solicited insights regarding the impact of scribes on patient volume, patient satisfaction, visit flow, and EMR documentation.

Scribes were asked about job skills needed, amount of training received, comfort in the exam room (both for themselves and patients), frequency of feedback received, balancing physician style with EMR documentation needs, and lessons learned.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the software SPSS V22.0. Univariate statistics were used to analyze patient and physician satisfaction, as well as clinic volume, time tracking, and EMR documentation. Initially, bivariate statistics were used to examine pre- and post-trial physician and patient data, but then non-parametric comparisons were used because of small sample sizes (and the resulting data being distributed abnormally). Detailed focus group notes were reviewed by all study investigators and summarized for dominant themes to support the quantitative evaluation. Lastly, the study was evaluated by the University of Massachusetts Institutional Review Board and was waived from review/oversight because of its QI intent.

RESULTS

Physician findings. Fifty-five physician surveys were completed during the 6-month period (TABLE 2). All of the physicians who were asked to complete this short survey at the end of the day (after reviewing notes with their scribe) did so. Physicians reported a high degree of satisfaction with collaboration with scribes. Their comments reflected positive experiences, including an improved ability to remain on schedule, having assistance finding important information in the record, and having notes completed at the end of the session.

TABLE 3 shows high satisfaction with clinical roles and colleagues with no substantive changes over time regarding these questions. However, the incorporation of scribes had a positive impact on issues related to physician morale, due to changes in paperwork, administrative duties, and work schedules.

Review of patient scheduling and documentation (TABLE 4) revealed visits per clinical session increased 28.8% from 6.6 to 8.5, and for sessions with 10 or more appointment slots available, billable visits increased 9.2% from 8.7 to 9.5. This increase was a result of adding an additional appointment slot to the schedule when a scribe was assigned and a greater physician willingness to overbook when scribe assistance was available.

A comparison of time tracking pre- and post-intervention showed a 13% decrease in time spent in the clinic, from a 3-week average of 30.1 hrs/wk to 26.1 hrs/wk (TABLE 4). Time spent working at home decreased 38%, from a 3-week average of 2.9 hrs/wk to 1.8 hrs/wk. These reductions occurred despite average scheduled clinic hours being 18% higher (35.5 vs 30.1) during the post- vs pre-intervention measurement periods.

Patient findings. TABLE 1 summarizes the 313 patient responses. Less than 10% of patients declined to have a scribe during the visit. Patients reported a high level of comfort with the scribe and indicated that having a scribe in the room had little impact on what they would have liked to tell their doctor. Nearly all open-ended comments were positive and reflected feelings that the scribe’s presence enabled their provider to focus more on them and less on the computer.

Focus group findings

The scribe focus group identified a number of skills thought to be necessary to be successful in the job, including typing quickly; having technology/computer-searching strategy skills; and being detail-oriented, organized, and able to multitask. Scribes estimated that it took 2 to 6 weeks to feel comfortable doing the job. Physician feedback was preferred at the end of every session.

Lastly, the 4 scribes identified several challenges that should be addressed in future training, such as how to: 1. document a visit when the patient has a complicated medical history and the communication between the doctor and the patient is implicit; 2. incorporate the particulars of a visit into a patient’s full medical history; and 3. sift through the volume of previous notes when a physician has been seeing a patient for a long period of time.

The nurses’ focus group identified many positive effects on patient care. They reported no significant challenges with introducing scribes to patients. Improvements in timely availability of documentation enhanced their ability to respond quickly and more completely to patient queries. The nurses noted that the use of scribes improved patient care and made them “a better practice.”

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the use of scribes in a busy academic primary care practice substantially reduced the amount of time that family practitioners spent on charting, improved work-life balance, and had good patient acceptance. Our time-tracking studies demonstrated that physicians spent 5.1 fewer hrs/wk working—4 fewer hrs/wk in the clinic, and 1.1 fewer hrs/wk outside of the clinic—while clinical hours and productivity per session increased. Patients reported high satisfaction with scribed visits and a willingness to have scribes in the future. Creating notes in real time and having immediate availability after the session was a plus for nursing staff in providing follow-up patient care.

Concerns by physicians that having another person in the room would alter the physician-patient relationship were not substantiated, perhaps because the staff routinely obtained consent and explained the scribe’s role. Consistent with previous work, we found no suggestion that a scribe’s presence affected patients’ willingness to discuss sensitive issues.9 Patients reacted positively to scribes who enabled physicians to focus more on the patient and less on charting.

Despite increased patient volume, physician morale improved. Physicians left work more than an hour earlier per day, on average, and spent over 1 hour less per week working on clinical documentation outside the office. Physician surveys showed an improvement in perceptions of how much work encroached on their personal life, consistent with the time-tracking data. These results have significant implications for clinician retention, productivity, and satisfaction.

Since our site is an academic training site, one might wonder how residents and advanced practitioners viewed this implementation, as they were not initially included. From the perspective of the administrators, this was a feasibility study. Clinicians who were not included understood that if this pilot was successful, the use of scribes would be expanded in the future. In fact, because of these positive results, our institution has expanded the scribe program, so that it now covers all clinical sessions for faculty in our center and is rolling out a similar program in 3 other departmental academic practices.

Financial implications. At the beginning of this initiative, our institution required that we cover the cost of the program plus generate a 25% ROI. Using a conservative 9.2% increase in billable visits, we extrapolated that utilizing 2 FTE scribes would result in an additional 860 visits annually. Per our hospital’s finance department, estimated revenue generated by our facility-based practice per visit is $196, including ancillaries. That means that additional visits would generate an estimated $168,600 annually—more than twice the $79,500 annual cost of 2 FTE scribes, yielding a 112% ROI. Furthermore, patient access improved by making more visits available. Beyond the positive direct ROI, the improvements in physician morale and work-life balance have positive implications for retention, likely substantially increasing the long-term, overall ROI.

Challenges. Implementing a new program in a large organization proved to be challenging. The biggest hurdle was convincing our institution’s administration and finance department that this new expense would pay for itself in both tangible (increased visits per session) and intangible (increased physician satisfaction and retention) ways. A cost-sharing arrangement proposed by our department’s administrator convinced hospital administration to move forward. Additional challenges included delays in getting the scribe program started because of vendor selection, purchasing new laptops for scribes, hiring and training scribes, developing new EMR templates, validating provider productivity, and legal/compliance approval of the scribe’s EMR documentation processes to meet third-party and accuracy/quality requirements—all taking longer than anticipated. However, we believe that our results indicate significant potential for other primary care practices.

Limitations. The number of physicians in the study was small, and they all worked in the same location. Social desirability could have biased patient and provider feedback, but our quantitative results were consistent with subjective assessments, suggesting that information bias potential was low. Patient and provider survey findings were also supported by qualitative assessments from both scribes and nursing staff. The size of the project did not lend itself to an analysis controlling for clustering by physician and/or scribe. The focus group discussions were not subject to rigorous qualitative analysis, potentially increasing the risk of biased interpretation. Lastly, we did not have the ability to directly compare sessions with and without scribes during the pilot.

Similarity to other findings. Despite these limitations, our findings are remarkably similar to those of Howard, et al,16 on the pilot implementation of scribes in a community health center, including good patient and clinician acceptance and increased productivity that more than offset the cost of the scribes. We expect that others implementing scribe services in primary care settings will experience similar results.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen T. Earls, MD, 151 Worcester Road, Barre, MA 01005; stephen.earls@umassmemorial.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Barbara Fisher, MBA, vice president for ambulatory services; Nicholas Comeau, BS; and Brenda Rivard, administrative lead, Barre Family Health Center, UMassMemorial Health Care, in the preparation and execution of this study.

1. Walker K, Ben-Meir M, O’Mullane P, et al. Scribes in an Australian private emergency department: a description of physician productivity. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:543-548.

2. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

3. Expanded scribe role boosts staff morale. ED Manag. 2009;21:75-77.

4. Scribes, EMR please docs, save $600,000. ED Manag. 2009;21:117-118.

5. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:399-402.

6. Cabilan CJ, Eley RM. Review article: potential of medical scribes to allay the burden of documentation and enhance efficiency in Australian emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 2015 Aug 13. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Hegstrom L, Leslie J, Hutchinson E, et al. Medical scribes: are scribe programs cost effective in an outpatient MFM setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:S240.

8. Campbell LL, Case D, Crocker JE, et al. Using medical scribes in a physician practice. J AHIMA. 2012;83:64-69.

9. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, et al. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184:258-262.

10. Hafner K. A busy doctor’s right hand, ever ready to type. The New York Times. January 12, 2014. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/14/health/a-busy-doctors-right-hand-ever-ready-to-type.html?_r=0. Accessed February 6, 2017.

11. Brady K, Shariff A. Virtual medical scribes: making electronic medical records work for you. J Med Pract Manage. 2013;29:133-136.

12. Baugh R, Jones JE, Troff K, et al. Medical scribes. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28:195-197.

13. Grimshaw H. Physician scribes improve productivity. Oak Street Medical allows doctors to spend more face time with patients, improve job satisfaction. MGMA Connex. 2012;12:27-28.

14. Morehead Associates, Inc. UMassMemorial Health Care: Physician Satisfaction Survey. 2013.

15. Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, et al. Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37:1174-1182.

16. Howard KA, Helé K, Salibi N, et al. BTW Informing change. Blue Shield of California Foundation. Adapting the EHR scribe model to community health centers: the experience of Shasta Community Health Center’s pilot. Available at: http://informingchange.com/cat-publications/adapting-the-ehr-scribe-model-to-community-health-centers-the-experience-of-shasta-community-health-centers-pilot. Accessed November 6, 2015.

1. Walker K, Ben-Meir M, O’Mullane P, et al. Scribes in an Australian private emergency department: a description of physician productivity. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:543-548.

2. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

3. Expanded scribe role boosts staff morale. ED Manag. 2009;21:75-77.

4. Scribes, EMR please docs, save $600,000. ED Manag. 2009;21:117-118.

5. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:399-402.

6. Cabilan CJ, Eley RM. Review article: potential of medical scribes to allay the burden of documentation and enhance efficiency in Australian emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 2015 Aug 13. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Hegstrom L, Leslie J, Hutchinson E, et al. Medical scribes: are scribe programs cost effective in an outpatient MFM setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:S240.

8. Campbell LL, Case D, Crocker JE, et al. Using medical scribes in a physician practice. J AHIMA. 2012;83:64-69.

9. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, et al. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184:258-262.

10. Hafner K. A busy doctor’s right hand, ever ready to type. The New York Times. January 12, 2014. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/14/health/a-busy-doctors-right-hand-ever-ready-to-type.html?_r=0. Accessed February 6, 2017.

11. Brady K, Shariff A. Virtual medical scribes: making electronic medical records work for you. J Med Pract Manage. 2013;29:133-136.

12. Baugh R, Jones JE, Troff K, et al. Medical scribes. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;28:195-197.

13. Grimshaw H. Physician scribes improve productivity. Oak Street Medical allows doctors to spend more face time with patients, improve job satisfaction. MGMA Connex. 2012;12:27-28.

14. Morehead Associates, Inc. UMassMemorial Health Care: Physician Satisfaction Survey. 2013.

15. Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, et al. Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37:1174-1182.

16. Howard KA, Helé K, Salibi N, et al. BTW Informing change. Blue Shield of California Foundation. Adapting the EHR scribe model to community health centers: the experience of Shasta Community Health Center’s pilot. Available at: http://informingchange.com/cat-publications/adapting-the-ehr-scribe-model-to-community-health-centers-the-experience-of-shasta-community-health-centers-pilot. Accessed November 6, 2015.

Is extended-release oxybutynin (Ditropan XL) or tolterodine (Detrol) more effective in the treatment of an overactive bladder?

BACKGROUND: Anticholinergic medications are the mainstay of pharmacologic therapy for an overactive bladder (defined as urge incontinence, urgency, or frequency). Immediate-release oxybutynin and tolterodine (the most popular options) are equally effective, but tolterodine has a better side effect profile. The efficacy and tolerability of the newly developed extended-release oxybutynin is compared with tolterodine in this study.

POPULATION STUDIED: The investigators enrolled 378 mostly white (87%), mostly women (83%) participants aged 21 to 87 years (mean=59 years); 88% of the participants completed the study. The patients were required to experience between 7 and 50 episodes of urge incontinence per week and 10 or more voids in a 24-hour period. The study was conducted in 37 specialty outpatient-based practices across the United States. Previous exposure or response to therapy did not preclude participation. Patients were excluded if they had uncontrolled medical conditions, significant risk for urinary retention, or incontinence related to prostatitis, interstitial cystitis, urinary tract obstruction, urethral diverticulum, bladder tumor, bladder stone, prostate cancer, or urinary tract infection. Other exclusions included pelvic organ prolapse, pregnancy, and potential poor adherence to therapy.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This was a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) sponsored by the makers of oxybutynin. The study participants were treated for 12 weeks with either oxybutynin 10 mg per day or tolterodine 2 mg twice daily. Stratified randomization insured equal representation of mild incontinence (≤21 episodes weekly) and moderate to severe incontinence (>21 episodes weekly) within each treatment group. Study visits occurred at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. Each subject kept a 24-hour urinary diary documenting micturition frequency and the number and nature of incontinence episodes during the 7-day period before each study visit. The participants were asked at each visit about adverse events or unusual symptoms. This study was well designed, avoiding bias with a double-blind double-dummy stratified randomization approach. Dropout rates were similar for the 2 groups. Formal intention-to-treat analysis was not possible, but the authors stated that analysis of partial data from dropouts was not different from reported results. The study may not be generalizable to most primary care populations, since patients were recruited exclusively from specialty practices. The authors adjusted for the nonsignificant baseline differences in incontinence frequency; this is statistically valid but not necessary in an randomized controlled trial. Without this adjustment, outcome differences between the 2 medications were substantially smaller and no longer statistically significant.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measured was baseline versus end of study (week 12) episodes of urge incontinence. Total episodes of incontinence, micturition frequency, and medication side effects were secondary outcomes.

RESULTS: Both treatment groups showed a substantial reduction in urge incontinence, total incontinence, and micturition frequency. Urge incontinence decreased 76% in the oxybutynin-treated group and 68% in the tolterodine-treated group (P=.03). Total incontinence episodes in the oxybutynin-treated group dropped 75% from 28.6 to 7.1 episodes per week, while decreasing 66% from 27.0 to 9.3 episodes per week in the tolterodine-treated group. The net difference between the groups was 3.8 (P=.02) or 2.1 (P=NS) fewer episodes of incontinence per week with extended-release oxybutynin, adjusting or not adjusting for the baseline difference between the groups. Weekly bathroom trips declined by 27% in the oxybutynin-treated group versus 22% in the tolterodine-treated group (P=.02). Rates of side effects were similar for oxybutynin compared with tolterodine.

Oxybutynin and tolterodine both produce a marked decrease in symptoms in patients with an overactive bladder. These medications have a similar cost ($78 monthly) and side effect profile, but extended-release oxybutynin is modestly more effective than tolterodine. This small advantage may be important to patients in whom a decrease of 2 to 4 fewer episodes of incontinence per week represents a substantial improvement. However, the combination of anticholinergic medication and behavioral therapy provides an even greater benefit than pharmacotherapy alone.1

BACKGROUND: Anticholinergic medications are the mainstay of pharmacologic therapy for an overactive bladder (defined as urge incontinence, urgency, or frequency). Immediate-release oxybutynin and tolterodine (the most popular options) are equally effective, but tolterodine has a better side effect profile. The efficacy and tolerability of the newly developed extended-release oxybutynin is compared with tolterodine in this study.

POPULATION STUDIED: The investigators enrolled 378 mostly white (87%), mostly women (83%) participants aged 21 to 87 years (mean=59 years); 88% of the participants completed the study. The patients were required to experience between 7 and 50 episodes of urge incontinence per week and 10 or more voids in a 24-hour period. The study was conducted in 37 specialty outpatient-based practices across the United States. Previous exposure or response to therapy did not preclude participation. Patients were excluded if they had uncontrolled medical conditions, significant risk for urinary retention, or incontinence related to prostatitis, interstitial cystitis, urinary tract obstruction, urethral diverticulum, bladder tumor, bladder stone, prostate cancer, or urinary tract infection. Other exclusions included pelvic organ prolapse, pregnancy, and potential poor adherence to therapy.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This was a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) sponsored by the makers of oxybutynin. The study participants were treated for 12 weeks with either oxybutynin 10 mg per day or tolterodine 2 mg twice daily. Stratified randomization insured equal representation of mild incontinence (≤21 episodes weekly) and moderate to severe incontinence (>21 episodes weekly) within each treatment group. Study visits occurred at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. Each subject kept a 24-hour urinary diary documenting micturition frequency and the number and nature of incontinence episodes during the 7-day period before each study visit. The participants were asked at each visit about adverse events or unusual symptoms. This study was well designed, avoiding bias with a double-blind double-dummy stratified randomization approach. Dropout rates were similar for the 2 groups. Formal intention-to-treat analysis was not possible, but the authors stated that analysis of partial data from dropouts was not different from reported results. The study may not be generalizable to most primary care populations, since patients were recruited exclusively from specialty practices. The authors adjusted for the nonsignificant baseline differences in incontinence frequency; this is statistically valid but not necessary in an randomized controlled trial. Without this adjustment, outcome differences between the 2 medications were substantially smaller and no longer statistically significant.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measured was baseline versus end of study (week 12) episodes of urge incontinence. Total episodes of incontinence, micturition frequency, and medication side effects were secondary outcomes.

RESULTS: Both treatment groups showed a substantial reduction in urge incontinence, total incontinence, and micturition frequency. Urge incontinence decreased 76% in the oxybutynin-treated group and 68% in the tolterodine-treated group (P=.03). Total incontinence episodes in the oxybutynin-treated group dropped 75% from 28.6 to 7.1 episodes per week, while decreasing 66% from 27.0 to 9.3 episodes per week in the tolterodine-treated group. The net difference between the groups was 3.8 (P=.02) or 2.1 (P=NS) fewer episodes of incontinence per week with extended-release oxybutynin, adjusting or not adjusting for the baseline difference between the groups. Weekly bathroom trips declined by 27% in the oxybutynin-treated group versus 22% in the tolterodine-treated group (P=.02). Rates of side effects were similar for oxybutynin compared with tolterodine.

Oxybutynin and tolterodine both produce a marked decrease in symptoms in patients with an overactive bladder. These medications have a similar cost ($78 monthly) and side effect profile, but extended-release oxybutynin is modestly more effective than tolterodine. This small advantage may be important to patients in whom a decrease of 2 to 4 fewer episodes of incontinence per week represents a substantial improvement. However, the combination of anticholinergic medication and behavioral therapy provides an even greater benefit than pharmacotherapy alone.1